1. Introduction

The Pāli Abhidhamma is certainly a more recent section of the canon, although within the Nikāyas, one can indeed identify some proto-Abhidhammic sutta, but this does not make it any less interesting [

1].

What the Abhidhamma pertains to, we could say in summary form, is a rigorous analysis of reality and cognitive processes. But although there have been attempts to define it as an ontology or a metaphysics, I believe that the most appropriate term—without detracting in any way from the legitimacy of the other two—is that of phenomenology.

The similarities and parallels that can be drawn between the Abhidhamma and the thought of Husserl are indeed remarkable, even though there is obviously no perfect coincidence. Nevertheless, a surprising convergence of intents and relatively similar methodologies of inquiry compel us to accept the Abhidhamma among the net contributors to a renewed phenomenology.

The objective of this paper, which is part of a work intended to be broader and thus to have further developments, is to propose an Abhidhammic phenomenology, in the comparison between Husserl and some main books of the Pāli Abhidhamma. Moreover, I will introduce the principal concepts of the Abhidhamma, indicating their genealogy starting from fundamental ideas found in the more archaic suttas, which we must assume to be at the origin of systematic Abhidhammic speculations. This work will specifically focus on the concepts expressed in the first two volumes of Husserl’s

Ideen zu einer reinen Phänomenologie [

2,

3] but also the

Cartesian Meditations [

4]. And for the Buddhist part, I will rely mainly on books such as the

Vibhaṅga [Vb] and the

Kathāvatthu [Kv] of the Abhidhamma and also the

Abhidhammattha-saṅgaha [AS] for general guidance, proposing occasional comparisons with the suttas of the Nikāyas.

The purpose of the Abhidhamma is to trace back to the fundamental constituents of phenomenal complexes [

1,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. It is acknowledged that in our experience, we attest to the appearing of a series of phenomena: A, B, C, and so forth. The phenomena are, moreover, in mutual relation to one another, but this is an issue we shall address later.

It is also acknowledged that a given phenomenon A is in reality something that appears to us as A by virtue of a certain conformation, that is, the aggregation of other phenomena, which, in their interaction (conformation) in a given way, conditionally determine the appearing of A qua A. These phenomena, in turn, may themselves be composed of others according to the same principle, and so on and so forth. If, therefore, we find that A is a conditioned entity determined by other conditioned entities

a1,

a2,

a3, ..., the intent of the Abhidhamma is to carry out a rigorous analysis (

vibhaṅga) of all conditioned entities, until reaching those conditioning constituents that are not susceptible to further levels of analysis, and these will thus be recognized as fundamental conditionings. The Abhidhamma gives the name

dhamma to these fundamental conditions [

7], thereby withdrawing this term from its more generic function of “thing”, “existent”, which it had in the suttas, and rendering it a specific technical term. The technical usage of the term

dhamma has changed significantly during the development of the Buddhist doctrine. Probably, it initially designated “the basic mental and physical qualities that constitute experience or reality” [

12] (p. 533).

Naturally, the Abhidhamma, in the persons of its authors, recognizes that this is an approximation, and at most a contemplative exercise. Nevertheless, it is extremely useful precisely as a contemplative exercise.

The idea that such an exercise is possible derives directly from the suttas, and specifically from two fundamental instances. One is constituted by the model of analysis of phenomena represented by the five aggregates (pañcakkhandha) and the chain of dependent origination (paṭiccasamuppāda). But it is specifically the model of the five aggregates that functions as the principal archetype and probably the authentic prototype of the Buddhist teaching. It asserts that every phenomenon we attest to (let us posit B this time) is analyzable and reducible to five fundamental factors.

These function not so much as models of interaction, which in their conformation in a certain way determine the appearing of the phenomenon B, but rather as layers that progressively develop around a fundamental core. From the essence of B, let us say b1, which is also the first aggregate of B, a process of complexification is triggered, which, around that essence b1, produces a further element that depends on b1 but adds a degree of complexity, a b2, or second aggregate that determines B—and so on with b3, b4, and b5. This is the model of the five aggregates, and it is easy to recognize the analytic principle that will inspire the phenomenal analysis of the Abhidhamma.

The second source of inspiration is the idea of the unconditioned (cf., e.g., [SN 43.12, AN 3.47, 4.34, 5.32, DN 34, MN 44, 115, Iti 90]). In the Pāli canon, it is often stated that there exist only two types of phenomena (

dhamma) that can be directly known (

dve dhammā abhiññeyyā). These are defined as conditioned phenomena (

saṅkhatā) and the unconditioned phenomenon (

asaṅkhatā). In essence, all attestable phenomena are conditioned because in all phenomena we attest to, the dependence (conditionality) on other phenomena (defined as “causes”) is recognizable. There is a single exception, which is

nibbāna [Iti 44]. It is the one and only unconditioned phenomenon. This distinction was later adopted by the Abhidhamma, probably inspired by what was said in MN 115 [

13] (p. 98).

This, moreover, raises a significant problem, which is the necessary consequence of this assertion: the unconditioned must also be the unconditioned condition of all conditioned things, since a conditioned entity cannot be founded upon itself precisely insofar as it is conditioned. For instance, there can be no “beyond” with respect to the asaṅkhata; therefore, no conditioned exists beyond the unconditioned. The latter does not arise (it does not appear as a phenomenon that manifests within a given circle, and is thus beyond every possible circle), and, therefore, it does not vanish either (just as it cannot manifest within a circle, it also cannot move outside of it, as other phenomena do), and it never changes; it is persistent and immutable (na uppādo paññāyati, na vayo paññāyati, na ṭhitassa aññathattaṃ paññāyati, [AN 3.47]).

This would appear to be confirmed by the explicit intent of contemplative practice to attain nibbāna (asaṅkhatagāmimaggo, [SN 43.11]), which, moreover, if it were an annihilation of being as some interpret it, would not explain why it is never defined as such, but rather as the unconditioned.

This idea of the unconditioned is taken up in the Abhidhamma, which will slightly modify its meaning. Nibbāna remains the only unconditioned [AS 6.32] non-phenomenal horizon insofar as it is the only unconditioned. However, within the series of conditioned phenomena, the authors of the Abhidhamma identify two distinct categories, and this distinction in some way echoes that of conditionality.

In the system of the five aggregates, a very important fact is implicitly affirmed, namely, the absolutely cognitive centrality of the entire system. This, however, does not translate into a naïve psychologism, but rather into a complex circuit that oscillates between two poles, opposite yet complementary, neither autonomous nor self-sufficient. The entire system of the five aggregates ‘occurs’ within the limits of this functional circuit, which is a biosemiotic circuit [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Form is the essential datum that triggers the whole process but in itself it has no value: it is its relation with a cognitive system, through contact (phassa, a term we must understand as strictly relational) that produces the second aggregate, “sensation” (vedanā), dependent on the sensory system, which is one pole of the functional circuit. This implies that form is to be understood as formal essence, or a fundamental perceptual mark. This relational oscillation (phassa) between sensor (vedanā) and effector (rūpa) is that around which the appearing of every phenomenon revolves. If the first two aggregates are the two poles of the circuit, the other three are the fundamental cognitive aspects around the circuit itself, and in fact, even in the Buddhist system, the last three aggregates form a subgroup called precisely cetasika, “cognitive factors”: perception (saññā), eidetic constructs (saṅkhāra), and consciousness or discernment (viññāṇa).

This centrality of the cognitive aspect in phenomenal processes is not accidental, but neither does it seek to support either an extreme psychologism—that all phenomena exist only in our minds—nor its opposite—that we are concerned only with the aspect of phenomena that is mentally apprehended, since we cannot know anything of their real and external objectivity. Indeed, the existence of an ‘external’ world independent of subjects is something that is rejected. The functional circuit described by the five aggregates is a unit of

what we perceive as “external” and

what we perceive as “internal”, but which in reality does not describe two distinct systems [

19].

There are certain fundamental ideas in Husserlian phenomenology that we shall take as examples for comparison with the Abhidhamma and for the reconstruction of a phenomenology that is entirely Abhidhammic.

What interests Husserl is the essence of things, a concept he expresses through the term εἶδος. By essence, however, one must not understand a distilled or fundamental ontological core of the thing as opposed to a sort of mental copy of it. In fact, Husserl rejects the separation between phenomenon and reality. It makes no sense to say that what appears to the senses is merely an imperfect image of the “true” physical object (“daß das erscheinende Ding ein Schein oder ein fehlerhaftes

Bild des “wahren” physikalischen Dinges sei”) [

2] (p. 110). It is misleading to think that what appears is merely a sign for something else that would be “truly real”.

What Husserl does recognize, however, is that different epistemological systems—biology, physics, anthropology, mathematics, and so on (to which we may rightly add traditional and religious systems of knowledge)—construct their own forms of knowledge based not on apprehending the thing in itself, but rather on what is recognized as useful to the system itself. This, however, entails an inevitable transformation of the thing into an object of knowledge functional to a given epistemology. Very little of the thing in itself remains, just as the sciences show little interest in lived experiences and pure experience. Psychology certainly does take interest, but always for the sake of the usable, and thus not in their purity, in their εἶδος.

Husserl’s proposal is to bracket all epistemologies. This does not mean denying them but merely suspending judgment (ἐποχή) on what they have to say and beginning again with a methodology for the investigation of phenomena that is rigorous but not influenced in any way by pre-established epistemological systems.

The second aspect of Husserl that interests us is the centrality of consciousness. In phenomenology, consciousness is necessarily an absolute. We have said that Husserl wants to remove every epistemological mediation from the analysis of the experiences of phenomena. Aiming, therefore, at an immediacy of experience, Husserl must perform a radical operation, namely, to posit consciousness as absolute.

Husserl recognizes that the experienced thing always presents itself within different horizons of signification, and phenomenology must take this into account. These different modes of signification—which are different ways of appearing of what is given—are effectively adumbrations in relation to the thing in itself. Yet, the signifying of the thing does not imply in this incompleteness an imperfection, such that the ‘total’ thing is necessarily implicit in all its adumbrations, experientially accessible to consciousness, as their very condition; that is, it remains analytically contained in all the signified existents.

What manifests through the adumbrations is part of the primordial manifestation that constitutes the formal mutuality, transcending the units within the manifold. The adumbrations are part of a continuum of determinations that, in certain cases, are concomitant and inseparable; such is the case, for instance, with determinations pertaining to color, which can never appear without a formal surface upon which to be displayed, or with luminosity, which is inconceivable and unmanifestable without a color [

3] (p. 131).

The aspect expressed in this context is the mutable dependence of the adumbrations. Although Husserl does not explicitly extend this to the entire continuum of appearing, it is evident that such an extension must be implicit in his claims. Just as certain adumbrations necessarily appear together, so too do the stream of consciousness and the continuum of the appearing of all adumbrations exist within a relational unity that constitutes their causal nexus. One example of this nexus is the relation between the body and the perceptual background: the body necessarily perceives things always from a certain orientation [

3] (p. 158).

In summation, everything that appears is conditioned, but the conditioned appear as placed in specific positional relations, which determine their complex configurations. Morphology is therefore the science of complex phenomena, since form (rūpa), a fundamental aggregate and thus the core (eidetic essence) of every phenomenon, is the key to understanding specific relations and causal connections.

Form is the essence, in the Husserlian sense (see

Section 2), of the conditioned. There exists no other typology for their determination. Since their only ultimate condition is the unconditioned, we must infer that the conditioned are the positional variations in the possible aspects of regions of the unconditioned.

The relation between two or more conditioned entities is the determining aspect of their positional morphology (saṇṭhāna). But since nothing, no essence or aspect, can exist beyond the series of conditioned things, then even the relational link is itself part of the conditioned process [AS 7.34].

The relating of two or more conditioned entities gives rise to the appearing of a complex conditioned entity [AS 8], but this does not lead to an indefinite or infinite regress. Rather, this relation sets the condition for the appearing of a complex conditioned entity, thus distinct from those that determine it but dependent on them for its appearing. This principle is defined as “aggregation” (khandha).

This must not result in an ontological hierarchy either, although the nuclear form, which remains the fundamental conditioned element of all complex conditioned entities of any degree, should indeed be considered the essence and thus the most important datum of a conditioned entity, which will have different forms related to one another as a condition for its appearing.

Everything that appears, appears as positional morphology of aspects (regions) of the series of conditioned entities [AS 8.27]. It follows that no sum of the totality of the series of conditioned entities can exceed the unconditioned.

The unconditioned is multiple but not “different”. On the contrary, a conditioned entity is seen as “arising, vanishing, and differ in its appearance” (uppādo paññāyati, vayo paññāyati, ṭhitassa aññathattaṃ paññāyati, [AN 3.47]). The perception of differences is given by the relation between two or more conditioned entities, but it is merely the principle of the function of the relation. Any conditioned A is given as A in opposition to all others (B, C, …), but this necessarily implies that it includes that to which it is opposed; otherwise, it would not be given as A. For if the opposition of A to B were the annulment of B, then A would have no way of defining itself as A.

There is nothing identical that can be given without the positing of its opposite. It follows that the world of conditioned entities described by the Buddhists is a polymorphic monism whose morphological aspects can never exceed the monistic nature of the unconditioned, which includes them all as their condition. Conditionality is not an ontological fact: the unconditioned does not “create” the conditioned inasmuch as it is already implicated in the unconditioned as simply its regions.

Every conditioned entity nonetheless necessarily implies the unconditioned, of which it is a holographic projection. The section of the whole thus retains the information of totality while being a reduction thereof. In order to contain the whole, each part is thus a sign of the whole

pansemantically [

20].

The unconditioned is not objective, but it is not subjective either. It is solely the total beyondness of the entire series of conditioned things. This condition is also expressed as lokuttara. In the Paṭisambhidāmagga 2.8, it is said that those who attain mindfulness are beyond the world: “they cross from the world [lokaṃ taranti], thus they are beyond the world (lokuttara); they cross over from the world [lokā uttaranti], thus they are beyond the world; they cross over from off the world [lokato uttaranti], thus they are beyond the world; they cross over from out of the world [lokamhā uttaranti], thus they are beyond the world”. The unconditioned is thus the only essential and substantial ontological center of gravity of conditioned phenomena.

2. Phenomenal Analysis: ἐποχή vs. vibhaṅga

One of the most well-known books of the Abhidhamma is precisely titled after the analysis (

vibhaṅga) of phenomena. By analysis (

vi-bhaṅga), the authors mean a reduction in phenomena to their minimal constituents, that is, to those that are found to be no longer susceptible to further degrees of analysis. These minimal constituents are precisely the

dhammas, and for this reason, they are also called “absolute” (

paramattha), whereas that which is aggregated from multiple interacting phenomena, and which is endowed with a conventional (

sammuti) identity shared by a collective, is called

paññatti (see

Table 1). The concept of the “ultimate” already appears in the suttas, mostly as a synonym for

yathābhūtaṃ; for instance, Snp 1.5 speaks of “knowing the ultimate as ultimate” (

paramaṃ paramanti yodha ñatvā).

On the other hand, a valid definition of the concept of fundamental phenomenon (dhamma) in the Abhidhammic system is that of the “constitutive element of complex phenomena which is not susceptible to further levels of analysis”.

The sammuti is also intended as “popular”, “common knowledge” [Kv 5.6].

It is important to note that the Abhidhammic absolute is not comparable to the

paramārtha of authors such as Nāgārjuna [

6] (pp. 72–75), [

20,

21,

22,

23]. In the latter, the absolute is a synonym for

nirvāṇa, whereas, as we shall see, the Abhidhammic

nibbāna can be understood as “unconditioned”, but it is not necessarily the only “absolute” entity, since this term refers solely to their quality as fundamental constituents—“essences”, as Husserl would say.

tattha vutt’ābhidhammatthā

catudhā paramatthato

cittaṃ cetasikaṃ rūpaṃ

nibbānam iti sabbathā.

Of the things contained in the Abhidhamma, fourfold are considered as pertaining to the ultimate, and thus are spoken therein: cognition, cognitive factors, forms, and Nibbāna.

[AS 1.2]

Cognition is considered to be ultimate as it can transcend the mundane dimension, thus becoming a supramundane (lokuttara) cognition [AS 1.3]. The Abhidhamma does not speak only of this. A fundamental part of the exercise of analysis is indeed the recognition of the internal or external nature of phenomena, or both (siyā ajjhattā, siyā bahiddhā, siyā ajjhattabahiddhā [Vb 2.3.1]). As in Husserl, the terminology must be understood in its philosophical context to avoid misunderstandings. When Buddhism speaks of the internal or external, it is not referring to the psyche and the world of objects. The internal is always understood as the experiential aspect, while the external is understood as the effectual aspect. What radically differs from the dualism between the psyche and objective world is that Buddhism does not consider these two spheres as autonomous but rather as two polarities of a unitary dimension, two aspects of a single and inseparable process. Therefore, in every phenomenon, one recognizes an internal and an external aspect, which are the two fundamental functions of experiencing it. Put another way, the subject experiences phenomena “as internal” and “as external”, despite their fundamental unity, due to the peculiar nature of its perceptual system and the relations it establishes in the form of isolating cognitions.

Of the fascicular chain of phenomena, in fact, only that which falls within the limits of perceptual possibilities is experienceable. Within this imaginary circle, phenomena appear, but only the partializations of them appear, those that find themselves within the bounds of the perceptual field. Everything that exceeds this simply does not appear. For Husserl, nothing can be said about it, but for the Buddhists, this is the fundamental problem of the limitation of the human perceptual field. And so, the phenomenon appears as having two faces: one tied to the experienced sensoriality and the other tied to its experienced exteriority by us, which refers to an isolation of the intended thing, felt as “autonomous” with respect to the intending.

The unity of all this is defined as dhātu [Vb 3.1], “the element”, the experienceable, and it has six natures: solid, liquid, fiery, pneumatic, spatial, conscious (pathavīdhātu, āpodhātu, tejodhātu, vāyodhātu, ākāsadhātu, viññāṇadhātu). Each of these elements then has two fundamental aspects: internal and external (atthi ajjhattikā, atthi bāhirā). The relational modalities of the two aspects of the elements are given by a series of fundamental connections, based on a triadic model: a relational axis between the two aforementioned poles—sensoriality and effectuality (S/E)—mediated by the relational nexus, which is consciousness. Sensoriality is represented by the six sensory channels (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind), while the six corresponding effectualities are considered objects that can be intended by these sensors: the visible, the audible, and so forth. The nexus between the two is a consciousness of the same nature as the sensor:

cakkhudhātu, rūpadhātu, cakkhuviññāṇadhātu, sotadhātu, saddadhātu, sotaviññāṇadhātu, ghānadhātu, gandhadhātu, ghānaviññāṇadhātu, jivhādhātu, rasadhātu, jivhāviññāṇadhātu, kāyadhātu, phoṭṭhabbadhātu, kāyaviññāṇadhātu, manodhātu, dhammadhātu, manoviññāṇadhātu.

[Vb 3.2]

Some interesting points to note include the following: The visible element is represented by form, here not understood as a generic cognitive form but specifically as an observable form. Secondly, the actuality of the organ of thought (manodhātu) is the phenomenon itself (dhammadhātu).

If there is a thought, there must also be a thinker, and we will have the opportunity to return to the observational standpoint of this thinker. The Buddhist contemplative exercise aims to deconstruct all compositeness (khandhas), and the psychophysical self, the sociocultural identity that a subject assumes for themselves, that is, the attā, is the most significant example of this composite factor. The attā is indicated several times in the canon as an aggregated factor, or as the most well-known example of the five aggregates, and thus, its deconstruction is of fundamental importance for early Buddhism. This fundamental truth is repeated also in the Abhidhamma, where the self is said not to be known as an ultimate (paramattha) fact precisely because it is analyzable into its aggregate constituents. The same is true for the notion of subject (puggala): “Therefore it is surely wrong to sustain that the subject is known in the sense of a real and ultimate fact” (tena hi puggalo upalabbhati saccikaṭṭhaparamatthenāti, [Kv 1.1]).

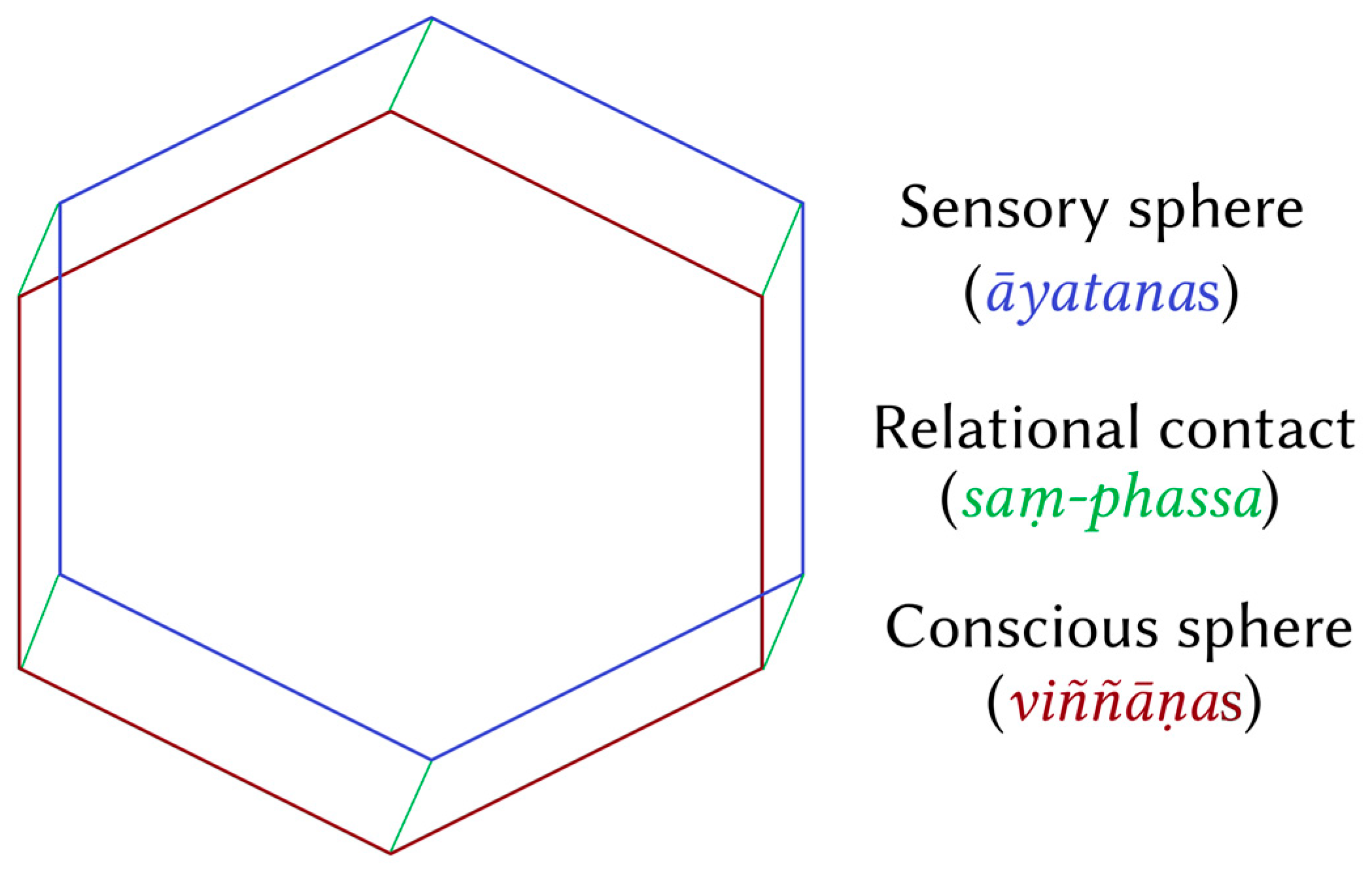

However, what truly allows the subsistence of a factor of aggregation, including the self, is the belief in the existence of the sensory spheres, indicated by the Abhidhamma as the very bases of conceptual thought and therefore meticulously analyzed [Vb 2]. These are referred to precisely as spheres (

āyatana), meaning by this term a certain domain of scope, a value-laden “field”. There are twelve basic spheres (

dvādasāyatanāni) constituted by the sensory organ and the actual element (

cakkhāyatanaṃ, rūpāyatanaṃ, [Vb 2.3]), thus six “internal” and six “external” (

chāyatanā ajjhattikā, chāyatanā bāhirā, [Vb 2.3.2.10]) in the sense in which we have come to understand internal and external—that is, the two poles (united in a functional unity) of perceptual experience (see

Figure 1).

In the Abhidhamma, each sensory organ is also called a “door” (dvāra), as it is considered a channel through which the specific sensation passes. Sometimes, the doors are grouped into two categories: the first five doors are the proper sensorial organs, while the sixth, namely the mind-door (manodvāra), is considered the coordinator of the other five (manodvārāvajjanam eva pañcadvāre votthapanakiccaṃ sādheti, [AS 3.9]).

In Buddhist doctrine, as in the Abhidhamma, the condition of being yoked to these percepts and thus to this oscillation between the two poles is a cause of suffering, and among the modalities of the cessation of suffering (dukkhanirodho), we read of what is also described in SN 10 and DN 22, as well as in numerous other suttas that mention this practice, namely the satipaṭṭhānā. With a slight variation from the suttas, we read that the correct application of mindfulness (sammāsati, [Vb 4]) lies in engaging in contemplative exercise in four distinct aspects, each with two modes removing covetousness and mental pain in the world: the body in the body, the sensation in the sensation, the cognition in the cognition, and the phenomenon in the phenomenon:

kāye kāyānupassī viharati ātāpī sampajāno satimā, vineyya loke abhijjhādomanassaṃ; vedanāsu vedanā …pe… citte citta …pe… dhammesu dhammānupassī viharati ātāpī sampajāno satimā, vineyya loke abhijjhādomanassaṃ.

[Vb 4.1.4]

If we read the

satipaṭṭhānasutta, we notice that the nature of this duality is attributed to the double aspect these factors possess “as internal” and “as external” (

iti ajjhattaṃ vā kāye kāyānupassī viharati, bahiddhā vā kāye kāyānupassī viharati…, [DN 22]). It is therefore not a matter of naïve realism [

24], already rejected as “extreme” in the foundations of archaic doctrine, but of a complex aspectuality concerning what phenomenologically we might call morphology and hyletic substrate: a mendicant meditates on the “body in the body” as the morphic aspect of the body and the hyletic substrate of the same—two sides of the same coin—and not, as might be understood from a naïve reading of “internal” and “external” [Vb 7], as the eidetic copy of a real and independent object apprehended by my senses (in the S/E system, see

Figure 1).

Ideas such as “external” (

bahiddha) and “internal” (

ajjhatta) are themselves conditioned. As concepts, they are percepts, and every percept has causes and conditions (

sahetu,

sappaccaya). Therefore, the reality of what is internal or external is valid only in relation to their conditioned nature, thus relative to the mundane circle to which they belong: the internal is predominantly understood by Buddhists as pertaining to the sensory spheres and to the subject’s experience [

18], thus as an inner world and a subset of the mundane circle, whereas the external is understood as the environment populated by effectors, but always within a mundane circle [SN 1.70, 12.44]. This dynamic holds value only in the world (

loka), and one does not transcend it by concentrating on the supposed external while ignoring one’s own experiential sphere. Since the internal and external are a dualism valid only in relation to a mundane circle, it follows that such concepts have no meaning in the transcendence of that circle.

In the first book of the

Ideen, Husserl distinguishes between sensile ὕλη, or

hyletic data, and μορφή, intentional [

2] (§85). The sensory data of the ὕλη refers to the sensible content of experience in its pre-intentional form, that is, not directed toward anything in a perceptual sense. The ὕλη does not possess meaning in itself but is merely the passive element of experience. In our functional circuit, it can be roughly equated with the

rūpa/effector.

On the other hand, the μορφή is that which, from the perceptual marks, is ‘transformed’ into an intentional object: that which gives “form” (μορφή) to the ὕλη as the object of intention. Ultimately, the morphological aspect is an aspect of meaning in relation to the object as a whole. This dichotomy can easily be mistaken for a form of dualism, which would render Husserl inconsistent, given his intent to maintain equidistance from both psychologism and materialism. However, if we understand it analogously to our functional circuit, these two elements are merely the poles between which the experience of consciousness oscillates, without thereby implying that they are autonomous and independent realities. It is not, in fact, a matter of a generative process whereby a morphological datum arises from a hyletic substratum: ὕλη and μορφή are, to some extent, inseparable. Indeed, by inverting the order (μορφή–ὕλη) and speaking of a

morpho-hyletic process, we become aware that we are confronted with the same semiosis as that of

nāmarūpa (note that in this case, μορφή, while denoting “form”, does not coincide, in Husserl’s usage, with the “form”/

rūpa of the Buddhists). The aspect of

nāma, for reasons I have discussed in a previous study [

18], can well signify the entirety of cognitive processes and thus the sensory pole of our circuit, whereas the formal aspect is precisely that of the perceptual–effectual mark.

Husserl, too, does not regard the hyletic data as “external” or “autonomous” in relation to the mind, but already as part of the circuit of the stream of consciousness as sensory givenness, and the same applies to the morphological data.

A similar issue is found in the two poles νόησις and νόημα, which describe an analogous process. For Husserl, νόησις refers to the

how of the intentional act—the subjective perceiving and conceiving of the thing—whereas νόημα is the

thing intended in itself, the object given as meaning in the act. In this circuit, the ὕλη is

part of the noetic side (νόησις), being the

how of the object’s givenness, while the μορφή is the structuring of the object as noematic data (νόημα) [

2] (p. 230).

In the Abhidhamma, a fundamental semiosic circuit is described. Its basis is the same oscillation between effector and sensor that is outlined in the more archaic texts, but to this two-pole circuit, the Abhidhamma adds a third, median element between the two: the act of designation. This constitutes the intervention of another pole in every respect, yet it differs from the two extremes insofar as it represents a possible mediation, which does not always operate. Indeed, if perception is mediated, then we will observe this intervention. Immediate perception, which is what the authors of the Abhidhamma aspire to, should eliminate this element.

In the oldest suttas, the mediating factor was seen as implicit in the sensor pole: it was believed that the act of designation was also inherent in the sensory sphere. Thus, to oscillate between the two aspects of fundamental semiosis,

nāmarūpa (

n/rσ) [

18], was an intrinsically designatory act. The disruption of this circuit—

the beyondness—instead entails the transcendence of this bipolarity.

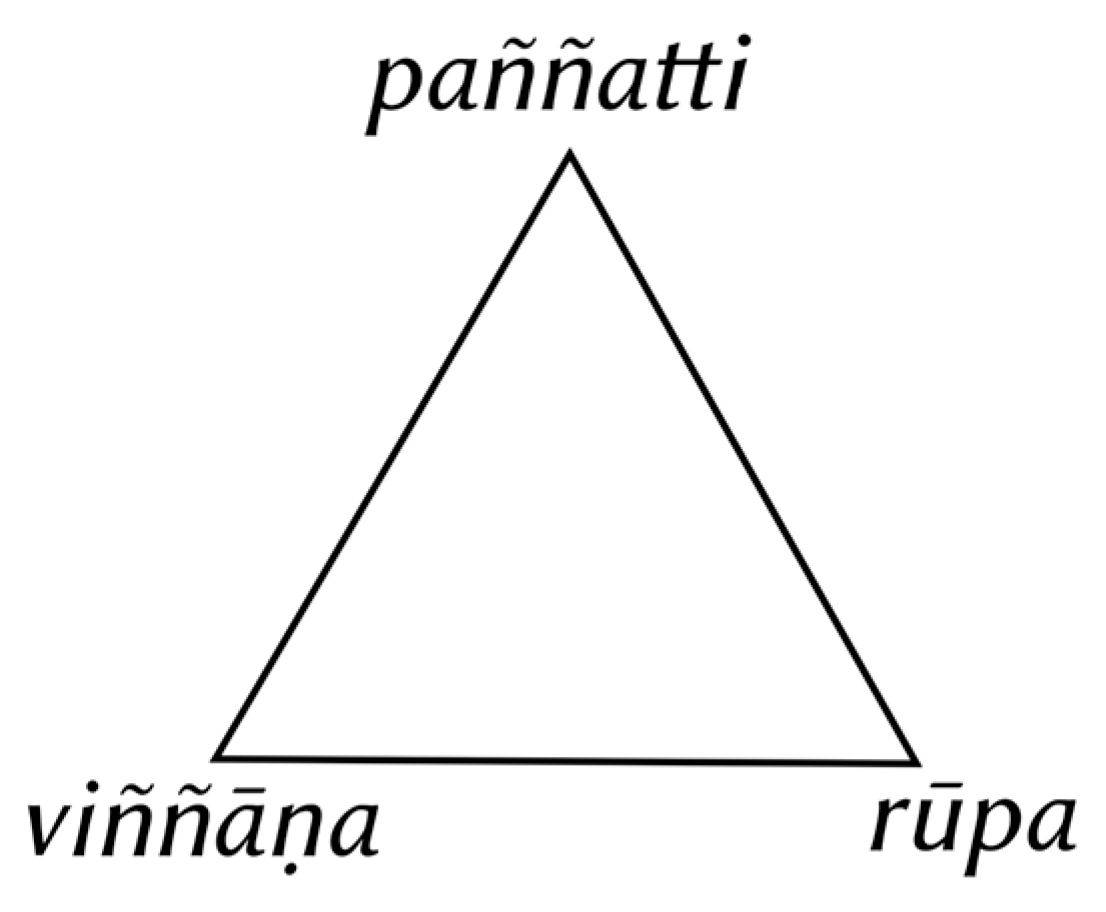

The Abhidhamma breaks down the nominal aspect into two parts: one that is exclusively cognitive (

viññāṇa)—though the intentionality of consciousness does not necessarily constitute a designation—and a designatory element (

paññatti), which may, when present, mediate the relationship between consciousness and form (see

Figure 2).

It is worth noting that, according to the Abhidhamma, the

nāmarūpa binomial is responsible for the six sensory spheres (

nāmarūpapaccayā saḷāyatanaṃ, [AS 8.3]). Also, these spheres are responsible for the arising of contact, and then from contact sensations arise (

saḷāyatanapaccayā phasso, phassapaccayā vedanā, vedanāpaccayā taṇhā). Consciousness, on the other hand, is dependent on conceptions (

saṃkhārapaccayā viññāṇaṃ) and is responsible for the name–form binomial (

viññāṇapaccayā nāmarūpaṃ). This statement is indeed a reprise of a very important concept already present in the suttas, namely mutual conditionality, and therefore reciprocal dependence [

18] between consciousness (the semiosis of discernment) and the name-and-form dyad (the fundamental semiosis). When, in the

Mahānidānasutta (DN, 15), it is asked, “is there a specific condition for name-and-form?” (

atthi idappaccayā nāmarūpan ti iti puṭṭhena satā, ānanda), the answer is that they exist dependent on consciousness (

viññāṇapaccayā nāmarūpan ti iccassa vacanīyaṃ).

The Buddhists distinguish between the process of the constitution of mental objects—which is precisely what Husserl seeks to deconstruct—and that of phenomenal conditionality, namely the process that leads to the appearing, the givenness, of a phenomenon as an aggregate of fundamental (other) phenomena in relation. This is an aspect that does not seem to interest Husserl. Furthermore, Buddhists distinguish these two phenomena on a hierarchical level (mental objects always originate from phenomena), but not on a functional level: the manner in which mental objects are constituted proceeds through the same processes of association and aggregation that describe the givenness of more fundamental phenomena. The only difference is the additional level of designation, which characterizes mental objects specifically. Yet designation can easily be understood as an additional layer of associative aggregation: namely, the attribution of a phonetic-signifying aggregate to a particular phenomenal relation in order to produce a designation of meaning.

In the Abhidhamma, the level of designated entities (

paññatti), i.e., conventional mental objects, is in turn divisible into two fundamental categories: the designated meaning (

atthapaññatti) and the designated signifier (

nāmapaññatti) [

6] (pp. 60–61). The designated concepts are thus divided into two categories: the concept that “is made known” and the concept that “makes known” (

tato avasesā paññatti pana paññāpiyattā paññatti, paññāpanato paññattī ti ca duvidhā hoti, [AS 8.29]).

As explained, the possible definitions are as follows:

…tathā tathā parikappiyamānā sankhāyati, samaññāyati, voharīyati, paññāpīyati ti paññattī ti pavuccati; ayaṃ paññatti paññāpiyattā paññatti nāma.

Such things are called “designated” insofar as they are conceived, recognized, understood, and expressed, and they are made known by means of, in consideration of, and with respect to this or that particular mode. These types of designates are thus called because they are that which renders known.

[AS 8.30]

If, on the one hand, the Abhidhamma aims to trace back to phenomena that are not susceptible to further degrees of analysis—that is, to phenomena that are in some way foundational—Husserl, on the other hand, proposes arriving at “essences”, which he describes in a very similar manner. When we thoroughly analyze how objects are given to consciousness, we ultimately arrive at foundational objects, which do not refer to anything else and are apprehended in simple, immediate theses. These original objects are the sensible objects [

3] (p. 17).

The ἐποχή is a fundamental prerequisite for subsequently undertaking the deconstruction of the object and reducing it to its fundamental phenomena, liberated also from the cognitive–cultural superstructure. This deconstruction, which proceeds from objects to phenomena, is in many respects analogous to the Abhidhammic analysis that proceeds from paññattis to dhammas.

Certainly, phenomenological analysis proceeds toward the phenomena up to the essence of their foundation, which is the conscious-relational structure itself.

As previously mentioned, the fundamental Abhidhammic concepts already find their origin in instances of the Pāli canon (see

Table 2). It is possible, without too much difficulty, to trace the origin of certain conceptions, just as has been carried out for the analytical methodology, which the Abhidhamma derives from exercises of decomposition of the chain of aggregates in the Pāli canon, or of the links of the chain of dependent origination.

By decomposing the causes and conditions of the arising of what appears to us, and by understanding their fundamental relational connections, one arrives at the essential dimension, which in many texts is also simply called “truth” (sacca). This term is used to indicate something incontrovertible, often in opposition to disputable ideas, conditions, beliefs, and opinions (diṭṭhi, micchādiṭṭhi), and although it is acknowledged that the brahmins may have their own sacca (itipi brāhmaṇasaccāni, itipi brāhmaṇasaccāni), it is recognized that the level of conviction is one thing, and another is that of reality, the only one that corresponds to truth as such. The same applies to what appears. Although things appear to us—deceptively—differently from the truth, there is an appearing in accordance with the true (yathābhucca), which is what contemplative practice aspires to: “there are other principles, O mendicants—deep, hard to see, hard to understand, peaceful, sublime, beyond the reach of logic, subtle, intelligible to the wise—which the Realized One makes known after having directly understood them through his own intuition. Those who sincerely praise the Realized One would speak of these things in accordance with the true” (… yehi tathāgatassa yathābhuccaṃ vaṇṇaṃ sammā vadamānā vadeyyuṃ, [DN 1]); and again: “thus, emptiness becomes manifest to them, in accordance with the true, undistorted, pure” (evampissa esā, ..., yathābhuccā avipallatthā parisuddhā suññatāvakkanti bhavati, [MN 121]).

If we were to describe how the Buddhists understood that which is “in accordance with the truth,” we would have to invoke two fundamental aspects: The first is the level of their ultimate essence, which is literally defined as suchness or thusness (

tathatā), which is the absolute truth of all that appears, that which can be said to conform to totality and therefore makes appear in accordance with such ipseity (

yathātatha). The second aspect is the level of the peculiar relational function of a specific aspect—its phenomenologically understood essence, that is, as it appears (

dhammatā). This is not yet the level of conventions and designations—that lies outside truth—but is something that already pertains to the specific regions of totality and is probably the concept from which the authors of the Abhidhamma derived the so-called “dhamma theory” [

7]. In earlier texts,

dhammatā is that which corresponds to appearing in accordance with essence, that is, as it is (

yathābhūta).

Some examples of this include the following: SN 12.20 uses tathatā to indicate an incontrovertible truth, “the fact that this is true, not unreal, not otherwise, and its specific conditionality is what is called dependent origination” (yā tatra tathatā avitathatā anaññathatā idappaccayatā, ayaṃ vuccati, ..., paṭiccasamuppādo). A similar formula is also found in the Abhidhamma [Kv 6.2].

Its mode of manifestation is yathātatha. For example, a Buddha is one who “knows directly the entirety of the world, and the entirety of the world in accordance with its suchness” (sabbaṃ lokaṃ abhiññāya, sabbaṃ loke yathātathaṃ, [AN 4.23; Iti 112]), or, “you should recognize them for their suchness” (taṃ viditvā yathātathaṃ, [AN 8.10]). Although this term may seem synonymous with yathābhūta, if we pay close attention to the contexts in which these words are used, we notice a significant variation in nuance. The term yathātathaṃ, which refers to tathatā, is concerned with an incontrovertible truth and with that which is in accordance with incontrovertible truth.

Conversely, yathābhūta indicates a thing as it is, but not necessarily because it is truth, but simply because it appears as it is after the work of reduction. Before, it appeared in another way, but the phenomenological–contemplative analysis aims to reach the as-it-is, that is, the essence of the thing. This is not about truth as the ultimate nature of all phenomena, but about the ultimate essence of the thing as a fundamental and irreducible characteristic. This is also the meaning of dhammatā, which is indeed what yathābhūta presumably refers to. In fact, the expression dhammatā esā [AN 10.2] can be vaguely translated as “natural”. However, that it refers to fundamental “principles” of phenomena is clarified by this passage: “pure equanimity and mindfulness, preceded by the investigation of essences; this, I declare, is liberation, the victory over ignorance” (upekkhāsatisaṃsuddhaṃ, dhammatakkapurejavaṃ; aññāvimokkhaṃ pabrūmi, avijjāya pabhedanaṃ, [AN 3.33]).

Naturally, the most used term is

yathābhūta, and it needs no explanation. As AN 3.33 also says, liberation is preceded by phenomenological analysis, the knowing of things as they are (

yathābhūtaṃ pajānāti), that is, in accordance with their essence (

dhammatā). It is

yathābhūta that directly expresses the most important and most frequent concept in the entire canon, and the insistence on

yathābhūtaṃ pajānāti informs us that, on the mundane level, such knowledge stands in contrast to what constitutes the world of semiosis [

18], that is, the world of

nāmarūpa, dominated by designations (

paññatti) and conventions (

sammuti). These terms were seldom used before the Abhidhamma, but the meaning is analogous: “and thus, when the aggregates are present, the convention we use to indicate them is ‘sentient being’” (

evaṃ khandhesu santesu, hoti sattoti sammuti, [SN 5.10]).

While on the one hand, Husserlian ἐποχή may be likened to the practice of

vibhaṅga in the Abhidhamma, it is interesting to observe how the three levels described in

Table 2 may loosely correspond to Peirce’s universal categories, and thus to the exercise of

phaneroscopy, which shares certain points of similarity with Husserlian phenomenology [

25,

26].

In the thought of Charles Sanders Peirce, a

phaneron is the subject matter of phenomenology. His distinctive inquiry into phenomena is termed

phaneroscopy, and his perspective likewise offers much from which we can learn. Peirce described this methodology in 1905 [

27]. Although Peirce was familiar with Husserl, his opinion of him was not particularly favorable, which prevented

phaneroscopy and phenomenology from merging too deeply or even from being regarded as sister disciplines in any meaningful sense.

Peirce does not distinguish the

phaneron from the phenomenon in any strict sense. His definition of

phaneron is used “to denote whatever is entirely open to assured observation, in all the entirety of its being, even if this observation be not quite as direct as that of a percept is” [

28] (p. 47). The former term, derived from the Greek φανερός, denotes a phenomenon but more specifically refers to “whatever is present at any time to the mind in any way” [

27] (p. 74). This is the definition we wish to adopt here. Although Peirce considered

phaneron a possible synonym for

phenomenon, we shall radically distinguish the two terms for our purposes. For instance, a

phaneron “resembles rather what many English philosophers call an

idea” [

28] (p. 48).

A

phaneron may also refer to the “collective totality” [

28] (p. 58) of whatever is present in the mind [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Peirce was careful to distance

phaneroscopy from psychology, as his aim was not to engage in speculation about the physiological facts underlying neurological processes but rather to focus on the constitution of thoughts as such.

For Peirce, a phaneron is a particular phenomenal aspect apprehended and attended to by the conscious mind—“whatever appears to the mind at a given moment”. Clearly, this definition diverges somewhat from Husserl’s notion of the phenomenon, though certain points of contact remain. What is of greatest relevance for us here is Peirce’s delineation of the universal categories intended to assist the philosopher engaged in phaneroscopy in recognizing phanera.

Peirce defines three levels of analysis of experience and thought.

Firstness refers to pure being, immediacy, unmediated experience, possibility, a quality not yet determined by identity, and intuition. In our experience of immediate things, a further layer is added to this aspect:

Secondness, which contextualizes the experience of a thing in relation to or in opposition with others. For Peirce, this is the “concrete” experience of a thing in its relational context. Finally,

Thirdness is the layer of mediation, meaning, interpretation, and above all, designation; for example, I see smoke, and, recognizing its identity as “smoke” and its relational implications with other identities, I infer the presence of another object called “fire”. A well-articulated proposal to compare Buddhist philosophy with Peirce’s phaneroscopy has been articulated by Lettner, especially in two important works [

38,

39].

3. Analysis of Consciousness: The Environmental Circuit

Consciousness is addressed in both systems of thought as a fundamental relational node set against a background of environmental, ecological nature.

The perception of normal cognitions is their limitation of experience within specific mundane circles. Cognitions are not capable, under normal conditions, of perceiving the unconditioned. This does not necessarily imply that the unconditioned is imperceptible, but merely that it is ultramundane (lokuttara) [AS 2.19].

The normal condition of cognitions is that of being circles or systems of circles. Any limitation of the conceivability of the conditioned in the form of a boundary is called a circle. There is an inside and an outside of this limit, and the conditioned are included within it partially and never the same at every moment due to the ambulant nature of the circle. It is the circle that moves, even when it appears to be still, and in this movement, different parts of the series of conditioned entities are processually revealed, giving the illusion of the world we know, populated by “objects” (i.e., designated identities of conditioned entities).

The relations among conditioned entities are interpreted as causal links, whereas they are positional relations, which reveal no more than the nature of the self-being of the conditioned. However, having only a partial view of what appears within the limits of one’s own circle, the human being sees only transformations, the arising and dissolution of things. In dissolution, for example, one sees the disappearing of configurations that previously conditioned the appearing, within one’s circle, of a given phenomenon.

The circle, too, is a (complex) conditioned entity, but above all, it is in relation to the other conditioned entities. However, its own relational links are what tend to most elude experience, as they are lived as implicit and underlying the things that appear more evidently. In general, causes are always more hidden than effects.

Given a circle (i.e., given a world), there is also necessarily and inevitably the possibility of its crisis, that is, of its rupture either through transcendence or through the collapse of its presuppositions. In the second case, the crisis is configured as a tragic event.

It is usually thought that archaic Buddhism lacks a reflection on intersubjectivity, as it appears to be more concerned with the deconstruction of individual attā. However, the strength of the interaction between different subjectivities within a shared background is evidenced precisely by the careful attention these authors dedicate to the problem of conditionality and the attribution of a common meaning to things. Indeed, by recognizing that every concept is the result of convention, the nature of this arbitrariness is immediately referred back to “common consent”, and this is the sense of the term paññatti, which already appeared prior to the Abhidhamma and which the latter recuperated in order to render it a technical term, denoting precisely the element of tension between the sensory pole and the effectual pole.

Only a community can establish a common agreement on conventional identities, and this also applies to intersubjective relationships, where “my” identity is also partly sustained by the recognition of others. The paradox of identity is that, in my ordinary experience, my perceptibility is grounded in a world of “objects”, of which I am the experiencer. Even the subjectivity of others is actually treated as an object, except that toward this specific object, I may feel empathy—that is, I direct toward my own body’s simulations of sensations that I imagine or see the other body experiencing. Even though I do not have access to the sensory dimension of the other’s body, I can imagine it, and this constitutes a paradox, a short circuit in the subject–object relationship upon which perception is based.

This “world of things” (Dingwelt) that we inhabit is not the world as it is but rather as it is most readily made available to our perception; once the object world has been constituted, it also becomes the foundation (the common field, gemeinsames Feld) for intersubjective dynamics, including the processes of designation.

Diese Dingwelt ist in unterster Stufe die intersubjektive materielle Natur als gemeinsames Feld wirklicher und möglicher Erfahrung der individuellen Geister, der Einzelnen und in erfahrender Vergemeinschaftung.

The equivalent of the process of designation (

paññatti) in Husserl is the environment constituted by common consensus (

Einverständnis konstituierende Umwelt [

3] (p. 193)), which is then the communicative environment (

kommunikative). The environment (

Umwelt) is a term of central importance for understanding the S/E axis. For Husserl, any subject is such only insofar as it is an environmental subject (

als Subjekt einer Umwelt [

3] (p. 185)). It follows, then, that the subject is in a relationship of mutual dependence with this environment. Husserl defines it in many other ways, such as “that which is perceived by the person in their acts, that which is remembered, grasped, thought—the world of which the personal Ego is conscious”. This ego “relates” to the world, intends it, but this world is

not to be understood as physical reality. Again, this is not a psyche/physis dualism, but it is the world as

intentionable: it is a cognitive fact of apperception [

3] (p. 186).

This

Umwelt finds some correspondence in the concept of

loka, which in the

sutta is described as having an origin (

lokassa samudaya) precisely in the S/E dynamic, listing the six sensory organs, the contact with their respective effectual elements, and the arising of the six consciousnesses determined by this contact (S/E ⟷ C) [

40]. According to the Abhidhamma [Kv 1.1], “it is said that the world is empty” (

suñño loko’ti vuccati) because, in this case, “emptiness” means “devoid of self and what pertains to the self” (

suññaṃ attena vā attaniyena vā). Furthermore, since the world is originated from the six sensory fields, their effectual contact, and the respective consciousness, and since each of these constituents is not autonomous nor self-sufficient (i.e., it is empty of a self) it can be said that the world is empty (

cakkhuṃ kho,

…,

suññaṃ attena vā attaniyena vā, rūpā suññā,

…,

pe,

…,

cakkhuviññāṇaṃ suññaṃ,

…,

cakkhusamphasso suñño,

…,

yampidaṃ cakkhusamphassapaccayā uppajjati vedayitaṃ sukhaṃ vā dukkhaṃ vā adukkhamasukhaṃ vā, tampi suññaṃ attena vā attaniyena vā).

Husserl also distinguishes between a relation of intentional type and one of real type [

3] (p. 215). Using Buddhist terminology, we could say that the intentional relation is the one established with any

paññatti, whether it is a mental construct or the appearing of a designation relating to the attestation of a certain phenomenal aggregate. For example, I may direct my intentionality toward that tree out there, and the fact that it appears to me as a “tree”, that is, as the

paññatti “tree”, makes it an intentional relation. But even if I evoke the image of a tree in my mind, it is a kind of intentionality no different from the former: this holds for both Husserl and the

Abhidhamma, which will always designate that mental tree as a

paññatti. All designable constructs are

paññatti, and therefore deconstructible into fundamental phenomena (

dhamma).

The sensory–type relation, which precedes the appearing of the

paññatti, that is, the very oscillation of the S/E axis, is instead understood by Husserl as a real relation. This type of relation depends on the S/E axis itself; otherwise, it naturally collapses. As proof of this, Husserl describes it precisely as a sensory–effector relation: “…Schwingungen im Raume sich verbreiten, meine Sinnesorgane treffen etc.” [

3] (p. 215).

The core of the Abhidhamma is analysis. The structure of analytical thought (paṭisambhidā) is recognized as having four fundamental objects, and it is worthwhile to dwell on them, as they reveal important aspects of the Abhidhammic conception. If these four objects are considered to be subject to analysis, it is due to their importance within cognitive mechanisms, which, as we recall, are understood in Buddhism as factors that imprison or lead to suffering when we are not their masters but instead allow them to lead us, a condition that characterizes the normal, usual state of the human being.

The four elements of Abhidhammic analysis are the analytical study of meaning (

atthapaṭisambhidā), the analytical study of phenomena (

dhammapaṭisambhidā), the analytical study of language (

niruttipaṭisambhidā), and the analysis of intellect (

paṭibhānapaṭisambhidā) [Vb 15.1]. The term

attha may refer not only to meaning but also to purpose. However, I consider that here it concerns the former, since it is likely intended to mean something very close to determined perception: perceiving something as having a certain identity designated by common consensus (

attha-paññatti). A similar issue concerns language more generally, which is indeed subjected to further analysis. According to Karunadasa [

6], the conception of language substantially refers to SN 22.62, in which it is defined as a matter of convention and is said to share a path alongside designation (

paññatti) and nomination (

adhivacana).

The mode of knowing (ñāṇa) is also subjected to analysis [Vb 16], and it is found that knowledge essentially depends on the articulation of five types of consciousness, accompanied by a cause that triggers their functioning (pañca viññāṇā, ..., sappaccayā). The consciousnesses are conditioned, formless phenomena (their form lies in the object with which they relate) and, above all, “mundane” (saṅkhatā, arūpā, lokiyā). The world is that which is composed of multiple elements (Husserl would say “objective world”), and thus it is nānādhātulokaṃ [Vb 16.10], of which the Buddha knows the ultimate essence (yathābhūtaṃ pajānāti). If there thus exists a cognitive relationship among the four things subject to analysis (meaning, phenomena, language, and intellect), we must presume that a logical connection also exists among these elements and that, being what we “know”, they are also the constitutive basis of the objects of the world (loka) subject to knowledge (ñāṇa). Both Vb 15 and Vb 16 seem to intend to render this connection implicit.

The five consciousnesses—which we must presume to be those relating to the first five senses, excluding mind-thought—are also said to depend on arising, to depend on having a referent object (recalling Husserl, consciousness is always consciousness of something), and to depend on having an “internal” base (i.e., a sensory organ) (pañca viññāṇā uppannavatthukā, uppannārammaṇāti uppannasmiṃ vatthusmiṃ uppanne ārammaṇe uppajjanti, ...) [Vb 16, Ekakaniddesa]. The circuit evoked here is that which exists between “internal” and “external”, understood as the sensory base and the effectual base.

For Husserl, the thing in itself would consist in the synthesis of all the meanings that appear in immanence, but we must doubt whether the Abhidhamma would agree, since the sum is always exceeded by the unconditioned, which otherwise would not be the essence of the foundation of all meanings or of all essences—but we shall come to that.

Meanings appear as such by virtue of their positional relation—as specific and aspectual regions of the thing in itself—with consciousness. Without the relationality between consciousness and these positional aspects, no meaning would appear in this way. What best expresses this concept of “meaning” in the Abhidhamma is the idea of paññatti, as we shall see later.

The Buddhists were also acutely aware of the centrality of the relationship with the positional aspects of appearings. Taking relationality into account radically changes the way phenomena and meanings are analyzed, but we must not understand the relationship between consciousness and the experienced thing as a mechanism or a process that follows from a condition of autonomy of either consciousness or the thing. We are accustomed to imagining that there are “things of the world” somewhere “out there”, beyond our perceptual sphere, which are autonomous and self-sufficient. With these, consciousness establishes a relationship, which consists in assimilating them into a cognitive datum that reproduces them in our brain. This is not the idea of a phenomenological relationship. Neither consciousness nor the thing can ever be given in isolation, but only in relation. Thus, the very appearing of the thing, in relation to consciousness, is the thing itself, which cannot be given—just as consciousness cannot be given—in any other way than in the specific positional aspect that constitutes the relationship with consciousness. This fact, too, has important consequences that we will explore. Husserl already recognizes that in its significant manifestation to consciousness, that particular aspect which appears is already one with it. In the Buddhist theory of mutual conditionality (paccaya), we will see that this is equally true. The bond is a positional nexus on par with those that describe the aspectual essences of the regions of the existents.

For Husserl, we must admit that it is in no way demonstrable that something exists independently of this relationship. Therefore, since consciousness (and its relationality) is the only thing of which we can be certain, Husserl takes it as absolute. This immanence of consciousness does not stand in opposition to an “outside”. Husserl denies a reality that is external and independent from the subject who experiences it. The relational nexus between reality (R) and experiencing consciousness (C) is a relation of

co-implication: R ⟷ C. In other words, consciousness is always relational; consciousness can never be given in any instance without its own relational nexus (“das Wesen des

Bewußtseins von Etwas”, [

2] (p. 69)).

In contrast, the naturalistic thesis to which Husserl is opposed posits a unidirectional dependence of the type R → C, and thus a reality that always transcends consciousness, upon which consciousness depends, but upon which reality itself does not depend in turn. This thesis is not rejected in principle (“dann

negiere ich diese „Welt“ also nicht”, [

2] (p. 65)), but its uncritical absolutization is rejected—no use is made of it, says Husserl: “

schalte ich aus, ich mache

von ihren Geltungen absolut keinen Gebrauch”. Indeed, Husserl does not deny the transcendent reality, just as he does not deny the world of objects, but he brackets it, “puts it out of play” (

Außerspielsetzen) [

4] (p. 60). If he were to explicitly deny it, he would fall into the second absolutism he seeks to avoid—namely, the psychologistic thesis according to which reality depends on consciousness (C → R), a thesis he often calls “subjective idealism”.

Husserl must arrive at the assertion that, with respect to the disappearance of the condition for the possibility of the reality that appears to signify, it must be said of the latter that both its existence and its non-existence are denied: ¬(ƎR ʌ ¬ƎR). This is a compromise aimed at eliminating all dogmatism and is therefore equivalent to stating ¬[(R → C) ʌ (C → R)]. This negation (¬) must not be understood in an ontological sense, in the sense that the possibility ¬Ǝ does not imply “non-existence” in terms of nullity or annihilation of the negated thing, but simply denies its givenness as a possibility. We could even indicate a second type of negation (~) as the negation of the affirmation. In that case, it would be well applied to the condition described by Husserl, who specifically asserts that he does not affirm either that the external reality exists or that it does not exist: ~(ƎR ʌ ¬ƎR).

The absoluteness of phenomenological consciousness is a consequence of this reasoning [

2] (§33). The pure ego is that which intends inasmuch as it

does not stand within the world understood as a world populated by objects—which is bracketed—and instead intends the world (of phenomena) in a phenomenological–transcendental sense. For Husserl, the ego intends the world insofar as it is

correlated to the world, but in order to be correlated to the world, it cannot be a part of it. Moreover, consciousness is that which confers meaning, and in order to do so, it must be independent from any further conferral of meaning upon itself. Without this pure absolute consciousness, there is no foundation of essence that allows for the deactivation of the two extremes: ¬[(R → C) ʌ (C → R)]. This is possible precisely on the basis of the assertion of a non-empirical subject. Consciousness is absolute in its role as the sphere of meaning conferral. From this, phenomenological analysis becomes possible.

From an experiential point of view—the only one that can be apodictically affirmed by our knowledge—that all lived experiences are given essentially only to consciousness (

Alle Erlebnisse sind bewußt, [

2] (p. 95)) is a matter of fact, which implies, with regard to intentional experiences (→), that they are not simply consciousness (I would add that this is because consciousness is primarily the network of relations) and thus the object (B) of a reflective gaze (A). On the contrary, this B is already present as background (

Hintergrund) and is therefore “ready to be perceived” (

wahrnehmungsbereit).

For Husserl, when I reflect on my lived experience, I grasp an absolute self, whose existence cannot be denied. It is not possible to doubt the presence of an immediately lived experience, because to do so would be a contradiction (“Richtet sich das reflektierende Erfassen auf mein Erlebnis [...] jeder trägt die Bürgschaft seines absoluten Daseins als prinzipielle Möglichkeit in sich selbst”, [

2] (pp. 96–97)).

However, we must note here a fundamental difference with Buddhist phenomenology. For Husserl, the thing in itself “transcends”; I only see its adumbrations, which constitute the phenomenon—the only attestable thing. However, for Buddhism, what must be considered is not only the conceptual and designative superstructure that clouds the immediate perception of the phenomenon but also the constitution of the phenomenon itself. While for Husserl the phenomenon is the only immanent and apodictic fact, it is a fact that must be considered and upon which an analysis can be conducted, beyond which one indeed comes closer to the apodictic essence. This comes very close to an idea of the thing in itself, which, however, Husserl brackets out, just as he sidelines the thing as an object reconstructed by an epistemological system and valued by historical–cultural categories.

Only the phenomenon, being certain insofar as it is attested, is of interest to the phenomenologist. For Husserl, this means arriving directly at things in an immediate way, without concepts contaminating the

Erlebnis. Everything is given to experience: the “things” we talk about, judge, or discuss are things of

experience (“...sind sie als Dinge der Erfahrung”, [

2] (p. 100)). And every concrete experience is always embedded in a context. But we can also consider eidetic (i.e., essential) possibilities of alternative ways in which these experiences could be given.

4. The Problem of Transcendental Consciousness (And Ego)

When we turn to the theme of consciousness, some interpretative difficulties arise. Consciousness is in fact fundamental in both “phenomenologies”, but while Husserl suspends judgment on its nature, basing his method on the apodicticity of consciousness as a point of observation, Buddhism is not very interested in this aspect but deconstructs consciousness as a flow of elaboration of real experience that alternates with phases of automatism, that is, of acting in the world in suspension of awareness. Consciousness is in short deconstructed in its dependence on temporality, but this does not imply that Buddhists deny the centrality of the experiencer—quite the opposite.

In the Abhidhamma [Kv 2.7], the momentariness view of consciousness is affirmed, that is, the idea that each unit of consciousness arises and ceases very rapidly, moment by moment, and does not endure for long periods, such as a day, a year, or an eon.

In another part of the Kathāvatthu [Kv 3.11], it is said that if there exist beings called “impercipient”, they cannot experience perception at all during their life. Otherwise, they would be like normal percipient beings—with a “fivefold” set of mental/physical components instead of just “body” alone. Their life would be constituted in a totally different manner. Thus, claiming that they are sometimes conscious is self-contradictory and absurd.

If this is true for perception, cognition works differently, and it is not active in all moments of a person’s life. The Abhidhamma acknowledges that there are phases in which the flow of automatic and involuntary thoughts (

bhavaṅga-citta) is interrupted, specifically when a particular

attention is required [

41]. At that point, it is held that the flow is interrupted by the attentive moment. Indeed, the Abhidhamma conceives of the cognitive process as a constant flow alternating between phases of automatism and moments of attention.

The concept of bhavaṅga has posed numerous interpretative challenges, often being associated with notions of the unconscious or subconscious. From a technical perspective, however, it more accurately refers to a form of suspended or automatic consciousness, a stage in which consciousness continues to function normally, but the attentive presence—typically active and focused on a specific object in other states—ceases to operate. Cognitive processes persist, but the degree of automatism increases.

From the standpoint of Buddhist psychology, the cognitive process can be described as an uninterrupted continuum, a perpetually active flow. What varies is the oscillation between different degrees of automatism. To conceptualize this, we might imagine two extremes of a spectrum: on one end, consciousness is fully present, meaning it is attentive and aware of its actions, as in contemplative exercises focused on the analysis of a specific object. More generally, whenever attention is focused, the cognitive process tends toward the presence end of the spectrum, albeit at varying levels. On the opposite end of the spectrum, there is a phase of progressively increased automatism, wherein the actions we perform—orienting ourselves in space, processing the cognitive data we receive from it, and responding accordingly—occur more automatically, without the active involvement of our conscious attention.

When we walk down the street, we are not constantly focusing our attention on everything processed by our sensory systems. In Buddhism, ‘sensors’ refer to the five traditional senses, each associated with a specific ‘sensory consciousness’, along with a sixth sense,

manas (literally, “thought”), which corresponds to a

manoviññāṇa, or a specific ‘mental consciousness’ [

42] that, in the Abhidhamma framework, serves as the “coordinator” of all sensory channels [

6] (p. 172). For instance, I may receive visual, auditory, olfactory, and tactile stimuli, and so forth, while my ‘thoughts’ proceed in a manner in which I am not necessarily aware. If, while walking, I perceive the sensory input ‘trees,’ my visual organ (

cakkhu) will process these data through its specific consciousness function (

cakkhuviññāṇa) without my necessarily being present in that act of processing, recognizing each time “this is a tree”—or more precisely, “this form (

rūpa) is what my perceptual conditioning conventionally associates with the nominal identity (

nāma) of tree”. These processes (

vīthi-pātha) typically occur automatically, given that the volume of data processed constitutes a constant and considerable flow. I do not necessarily need to engage my conscious attention to walk down the street, avoid obstacles, or ensure I do not collide with others. All of this occurs ‘automatically’.

As a state of consciousness, the bhavaṅga is rather referred to a type of function or moment that occurs between several cognitive phases constituting becoming. In ancient Buddhist psychology two states of cognition were included: the first is identified as processual (vīthi-citta) and contextually refers to the moments in which one is actually conscious, present to oneself. However, we are not conscious in every moment of the day. Numerous physiological processes are carried out unknowingly, and numerous daily actions are performed automatically, without our subjectivity being fully aware. This second state is called vīthi-mutta, and it is probably the origin of the subsequent elaboration around the state of bhavaṅga.

Certainly, there are moments when the situation demands the intervention of my conscious attention, such as an unexpected event or a situation requiring focus. In such instances, the flow of consciousness, which had proceeded automatically up to that point, is ‘interrupted’ by a series of stages in which cognition (citta) becomes attentive and aware. What the Abhidhamma emphasizes, however, is that the cognitive flow (citta) is never truly interrupted. What changes is the qualitative nature of this flow, which is sometimes dominated by the state of automatism (bhavaṅga-citta) and other times by more consciously attentive states, which intervene to ‘alter’ (calana) the previous (unperturbed) continuous flow of bhavaṅga (bhavange calite bhavangasotaṃ…, [AS 4.6]).

According to Smith [

43] (p. 459), “

bhavaṅga citta is a subliminal mental event that functions to sustain the causal continuity of the stream of consciousness when more ordinary sensory-cognitive events become dormant”. This flux is like a stream “that flows in the absence of ordinary sensory cognitive functions”.

From a modular perspective, we can envision this flow as an alternation between different phases. If we denote moments of conscious attention with a simple circle (〇) and those of bhavaṅga with a square (◻), we might represent the flow as follows:

...—〇—〇—〇—〇—◻—◻—◻—〇—〇—〇—〇—...

This could illustrate a cognitive flow in which conscious attention is engaged intermittently, alternating with moments when attention is suspended, and the ‘automatic pilot’ of

bhavaṅga takes over. For example, “when my visual system comes into proper contact with a visible object, a moment of visual consciousness arises” [

43] (p. 460). In the opposite scenario, where I am walking without focusing my attention, this automatic flow might be interrupted by a moment requiring my active attention, leading to something like this:

...—◻—◻—◻—◻—◻—〇—〇—〇—◻—◻—◻—◻—◻—...

Therefore, the role of the bhavaṅga-citta is to guarantee the continuity of the conscious process:

The bhavaṅga functions as a continuity guarantor that arises between each event cluster of perceptual-cognitive engagement with the world. As a visual experience subsides, a series of bhavaṅga citta-s arise, and as an auditory cluster begins, the bhavaṅga citta-s are disturbed and then cease with the arising of subsequent sensory modality-specific citta-s. These latter citta-s then provide the informational basis for subsequent mental activity that work up the basic sensory data into something robustly cognizable. The bhavaṅga citta is necessary in order to make sure the various sensory and cognitive event clusters that make up our ordinary waking state are continuous. According to the Abhidharmikas, there are gaps between each modality-specific event cluster, [and] the bhavaṅga citta fills these gaps.

Why is it important to consider this concept of bhavaṅga-citta? One might assume that Buddhist contemplative practice aims specifically at training the meditator’s cognitive process to sustain prolonged periods of conscious attention, which would also enable the practitioner to analytically engage (vibhaṅga) with processes that normally operate automatically and thus without their awareness. Such analysis would reveal how these automatic processes contribute to constructing a perception of reality based on cognitive mechanisms of attribution and designations of conventional identities, which, as previously stated, bear no relation to the factual reality of things (yathābhūtaṃ). These merely nominal entities (paññatti) do not constitute the fabric of reality. However, since we convince ourselves that the world consists of ‘things’ distinct from one another and endowed with autonomous, self-sufficient identities, we in fact live in an illusory world. While these mechanisms of segmenting reality serve a practical function, they have the side effect of distancing human beings from perceiving the real, rendering them isolated ‘things’ in turn.

Another aspect of fundamental importance concerns intentionality. The cognitive process directed toward a specific object, which Buddhists refer to as

phassa (literally, the contact between the cognitive sensor, such as the visual organ, and the sensory effector—the visual data that will be processed by visual consciousness), is an intentional cognitive process: consciousness is always consciousness ‘of something’, and this something is the cognitive object processed by the sensory organs and directed by the mind-thought [

43] (p. 472). However, what distinguishes this from the state of

bhavaṅga-citta is that the latter is not directed toward a particular object. We might refine the definition by stating that

bhavaṅga is not ‘focused’ on any specific object, although it remains active in processing sensory data. Otherwise, its very function would be undermined, as its role is to allow the automatic subsistence of the body without requiring the meticulous allocation of energy to the detailed processing of data.

This brings us to Smith’s proposal to consider the state of

bhavaṅga as, in fact, a form of pre-reflective attention. This is a highly compelling suggestion, as it does not deprive

bhavaṅga of its effective function but rather allows us to explain how this state of cognitive processing is indeed attentive to the surrounding environment—what Uexküll would describe as the

Umwelt [

44,

45]—without, however, introducing into this processing the precise perception of the identities of the surrounding ‘things.’ For this reason, Smith speaks of a ‘mental state’ endowed with a ‘semantic content’ distinct from that of pre-reflective awareness, though it would be more appropriate at this point to speak of a ‘pre-semantic’ or, even better, ‘pre-conceptual’ state: “

bhavaṅga is better thought of as a kind of primal sentience that makes the organism the kind of organism it is rather than a kind of thought it has about itself. In this way, I understand the reflexivity of

bhavaṅga citta as being similar to the view that just by being conscious of an object, sentient beings come to have a self-awareness that is logically and temporally pre-reflective” [

43] (p. 474).

Specifically, what bhavaṅga lacks is the influence of ‘cognitive constructs’, namely the data referred to as saṅkhāra, which function as organized clusters of information rendered ‘recognizable’ by our habits and attitudes toward the world.