2. Conceptions of the Name

In early Buddhism, reflection on one particular concept dominates: that of the “name” (nāma). Beyond its shared etymological root with the English “name” (cf. the Proto-West Germanic root *namō with Latin nōmen, Greek ὄνομα, and Hittite ḫannai-), we must not assume that this concept is perfectly equivalent. First and foremost, the Buddhist nāma serves a very specific function. While it partially overlaps with the Western linguistic notion of “name”, it also exceeds its boundaries in significant ways.

A careful analysis of the texts suggests that, in early Buddhist thought, nāma is primarily understood as a function capable of organizing the phenomenal continuum into discrete, recognizable units. However, the nature of this division is not derived from the phenomenal continuum itself but from the requirements shaped by sociocultural convictions, which expect that a given “thing” can be isolated, and thus manipulated. This expectation necessitates the intervention of “isolating cognitions” aimed at achieving this end. The rationale is therefore purely the convenience of knowledge systems that structure language. In short, the organizing principle is primarily one of usability. I will call this principle “isolating cognitions” for reasons that will become evident in the description of cognitive mechanisms.

Nāma appears, in fact, to be the pivot around which the entire early Buddhist conception of language revolves. It is part of a fundamental cognitive dyad (which it forms alongside rūpa), yet it also functions as an agent with its own specific characteristics. Furthermore, whether as part of the dyad or as an individual function (nāma indeed possesses its own characteristics), it holds a unique relationship with consciousness.

A concise but remarkably clear text on the idea of nāma can be found in SN 1.61, where we read:

- kiṃsu sabbaṃ addhabhavi,

- kismā bhiyyo na vijjati;

- kissassu ekadhammassa,

- sabbeva vasamanvagu

- “What oppresses everything?

- What has nothing greater than itself?

- What is the one thing that holds everything under

- its sway?”

The answer to these three questions is always nāma. From this brief text, it is already evident that early Buddhism did not regard language as a trivial matter. The name is seen as a universal oppressor so powerful that it holds everything beneath it, with none greater than itself (nāmaṃ sabbaṃ addhabhavi, nāmā bhiyyo na vijjati; nāmassa ekadhammassa, sabbeva vasamanvagu).

We must exercise great caution regarding this idea of the seemingly boundless power of a linguistic element and determine whether this is truly an exaggeration by the authors or whether their reflections on language lead them to such conclusions. To better understand this discussion, it is useful to analyze the suttas following SN 1.61, as well as the preceding one. A triplet very similar to

sabbaṃ addhabhavi, bhiyyo na vijjati, and

ekadhammassa, sabbeva vasamanvagu is, in fact, applied not only to

nāma (name) but also to

citta (cognition). In the subsequent sutta (SN 1.62), we find the following statements: “Cognition is what leads the world” (

cittena nīyati loko), “By cognition [the world] is drawn along” (

cittena parikassati), and finally, “Cognition is that one thing which has everything under its control” (

cittassa ekadhammassa, sabbeva vasamanvagu). This is, again, a very intriguing triad, partially overlapping with the functions of

nāma (name). Thus, we observe not only that name and cognition are interconnected, but also that cognition specifically relates to

loka (the world) and that both are functions associated with control. Moreover, they represent forces to which, in some way, we are yoked (they control us). This specific nuance is subtle but present in the text, especially when examined in relation to other suttas addressing the same themes. The following suttas more or less maintain the same line of argumentation but address different topics. In

Table 1, I have correlated all these assertions for comparative purposes.

From this comparison, we note further similarities. First, it must be noted that even though SN 1.64-65 are titled “fetters” and “bonds”, the theme is, in fact, desire, recognized as capable of creating (or acting as) fetters and bonds toward the world.

In the table, I compared the suttas from SN 1.61 to 1.65, but it should be said that the analysis continues in greater depth and involves numerous other concepts examined in this particular series of suttas. From a comprehensive analysis, we realize that the general theme appears to be loka, i.e., the “world”. This theme is thus linked to these five suttas but is also the central theme of the subsequent ones. SN 1.66 focuses on what harms the world (kenassubbhāhato loko), what surrounds it, and what has struck it down (namely: death, old age, and the dart of craving). SN 1.67 centers on what ensnares the world (uḍḍito loko), what surrounds it, and what grounds it (craving, old age, and suffering). We begin to recognize a very precise pattern. SN 1.68 discusses what closes off the world (pihito loko), what grounds it, what ensnares it, and what surrounds it (morality, suffering, craving, and old age). SN 1.69 addresses what imprisons, “binds”, the world (bajjhatī loko); that is, desire and craving; their removal will sever all bonds (icchāya vippahānena, sabbaṃ chindati bandhanaṃ). Finally, with SN 1.70, we arrive at the world itself. The suttas proceed with further analyses, such as health (SN 1.73), but these are not of interest in this context.

The description of the world provided in SN 1.70 is that it is “arisen in six” (

chasu loko samuppanno), forms a close bond in six (

chasu kubbati santhavaṃ), and through attachment to these six, the world is tormented (

channameva upādāya, chasu loko vihaññati). This sixfold structure, which constitutes what allows the arising of the phenomenon (

samuppanno) called

loka (“world”), and which is the foundation of its binding as well as the origin of its torment, refers to the only other significant sixfold structure known in the Pāli canon, namely the sensory spheres (

saḷāyatana) ([

20], pp. 116–117).

There is a reason I chose to analyze the suttas from SN 1.60 (which we will examine shortly) to SN 1.70. The reason is that they are part of a particular group of suttas dedicated to reflection on language and its relationship with the “world” [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

In a previous study, it has been demonstrated how the concept of

loka in early Buddhism is closely tied to perceptual–cognitive experience ([

20], p. 112). For this reason, the sixfold structure with which SN 1.70 associates it can only be the set of six sensory spheres, as evidenced by suttas that explicitly link the “phenomenon” of

loka to the perceptual–cognitive structure arising from contact (

phassa) between the effector and the sensor, producing a specific sensory consciousness (see, for example, SN 12.44, 35.107, 56.28, AN 4.23, Ud 3.10, Iti 112, and compare them, for example, with MN 146.6, SN 35.60, and AN 4.23). In all the major discourses on the theme of the “world”, it is treated as a “phenomenon” that “arises” from specific causes and conditions and that, in the absence of these bases to sustain its phenomenal appearance, naturally ceases along with its influence on human experience (see, for example, SN 35.85).

However, it is precisely the experiential dimension that is central to the conception of the world, which is primarily tied to sensory dynamics and the social conventions that organize these into recognizable percepts. The fact that the linguistic sign is a matter of convention, and not of presumed natural laws determining the identities of “things” independently of perceivers, is something Saussure emphasizes strongly ([

18], pp. 160–162). In particular, the proof of the arbitrariness of the linguistic sign lies in the mutability of semantic values ([

18], p. 154). Time leads to shifts in semantics, and thus signs never remain identical in their value. Time also brings about other changes: those of the signifier. Phonic execution is never perfectly identical, and languages “evolve”, i.e., they “change” the pronunciation of words over time ([

18], pp. 163–168), leading to considerable diachronic transformation ([

19], pp. 290–294). Above all, geographical and historical–cultural discontinuities are what also determine differences in the

values of signs. Speaking of the perception of linguistic sounds as something believed to be objectively determinable, as well as the relationship between the idea and the word associated with it, Saussure cautions, “Elle aussi ne représentera jamais qu’un des éléments de la valeur, et ce sera une illusion de croire qu’au nom de cette élément on puisse traiter par la psychologie pure les différents unités de la langue” ([

19], p. 290).

Variability is observed synchronically, as well, as languages evolve independently, and a certain community of speakers may develop tendencies that another nearby community does not ([

18], pp. 163–168). This was a fact well known to the Buddha, who, in a famous sutta, explicitly uses the issue of dialectal variability to illustrate how language is not, in itself, a reliable means for understanding reality or truth, but is rather a source of “opinions”, and thus of conflicts

5.

The fact that language (nirutti) and nominal labeling (adhivacana) is fundamentally a convention, a common agreement, and not a faithful representation of reality is also expressed through specific technical terms, such as paññatti (“designation”, “convention”), applied specifically to language (see SN 22.62: niruttipathā adhivacanapathā paññattipathā).

From the relationship connecting the group of suttas SN 1.61-70, we also understand that certain functions of the “world” are in fact closely linked to a particular aspect of language, which is determined by the peculiar object nāma, which I will proceed to define.

3. Origin of Conceptions on Language

The reasons behind the Buddhist focus on language likely have very ancient roots. Buddhist considerations on the theme of language and its connections with cognition and perception are grounded in the significance that words held in the Vedic world, where the ability to encode a message in the form of verses for oral transmission was a highly complex art requiring genuine specialization. The importance language assumes in these conceptions is akin to a phenomenal performative power, and the linguistic object is treated with utmost caution due to its potential. It is undeniable that these foundations fostered an attention to the theme of words that led to technical analyses of language and refined reflections on linguistic phenomena. This is true even though the nature of linguistic focus differs fundamentally between the Vedic and Buddhist traditions. In the Vedic tradition, language holds a sacred significance; it is a tool of technical power with a “magical” nature, and mastering it is the prerogative of specific technicians versed in this sapiential tradition. In Buddhism, however, language is perceived as what “chains” (saṃyojana) human beings to a particular “world” (loka).

Here, too, there is a divergence from the Vedic conception, in which the loka is something founded and preserved by a certain order. This order, recognized by Buddhists as a perceptual–cognitive system—namely, a psychosemantic organization of perceptions into well-defined normative structures—systems and frameworks that influence our experience of reality and “conform” us to specific orders, is precisely what their contemplative practice aims to dismantle. This represents a fundamental difference between the two approaches to contemplative practice.

Nonetheless, Buddhism is not radically opposed to the Vedic order; it respects much of its traditions and knowledge, positioning itself as a new interpreter of these elements. Conceptions of language are a clear example of this. Central in this regard is the importance of

Vāc, comparable to that of Agni in

Ṛgveda ([

26], p. 64). The sacred word has luminous properties, and Agni is its inventor (ṚV 2.9.4)

6. The Vedic poets are also inspired by this light, by Agni himself (ṚV 4.11.3).

A sutta that helps us navigate this topic is SN 1.60, the first in the group mentioned in the previous section, which I have reserved for analysis here. This sutta is dedicated to the figure of the kavi, a term we can translate as poet, but which, as we shall see, denotes a much broader figure. The sutta asks what is the basis of poetic verses (kiṃsu nidānaṃ gāthānaṃ), what is their distinguishing feature (kiṃsu tāsaṃ viyañjanaṃ), on what do they depend, and what do they imply (kiṃsu sannissitā gāthā, kiṃsu gāthānamāsayo). This brief sutta is one of many attestations of the profound knowledge Buddhists had of the preceding tradition, the importance of composing verses for encoding and transmitting knowledge, and the role of the kavi in all this. It is no coincidence that this sutta precedes the one on the name discussed earlier; in fact, the answer to these questions is that “meter is the basis of poetic verses, syllables are their distinguishing feature, verses depend on names, and a poet is one who underpins the verses” (chando nidānaṃ gāthānaṃ, akkharā tāsaṃ viyañjanaṃ; nāmasannissitā gāthā, kavi gāthānamāsayo).

The roles of poet and seer (ṛṣi) in the Vedic world are closely connected. The authors of the Vedas, those who first began codifying sacred verses, are considered to possess power comparable to that of deities, and the families that initiated this tradition are revered as divine. The Pāli canon knows and mentions these ten seers (Aṭṭhaka, Vāmaka, Vāmadeva, Vessāmitta, Yamadaggi, Aṅgīrasa, Bhāradvāja, Vāseṭṭha, Kassapa, and Bhagu) in some suttas, such as AN 7.52, and in DN 32, the epithet of Aṅgīrasa, the name of one of the most significant of these authors, is even attributed to the Buddha (aṅgīrasassa namatthu, sakyaputtassa sirīmato).

In the Vedas, the figure of the technician is much more clearly linked to that of the seer and the poet. Through poetic expression, complex knowledge unveiling the underlying connections (

bándhu) ([

27], p. 17, note 9) that sustain the world’s mechanisms are expressed, and such insights can only be seen by the extraordinary power of the seers. However, this poetic capacity is in itself described as a technical power, not only because, as is well known, since antiquity, composing in verse has been a complex art, requiring refined skills to maintain meter and convey messages with equally refined mnemonic techniques, but also because the role of the poet (

kaví) is closely connected to that of the

ṛṣi [

28], to the extent that it essentially embodies the same role, insofar as it is tied to the concept of possessing “potency” or “performative efficacy”

7, particularly in the use of words. Language, as well as its masterful command, is another theme linked with the archaic concept of τέχνη.

The fact that the role of Vedic language, that is, of poetry, was analogous to that of τέχνη is confirmed not only by comparative philological studies but also by the very terminology employed. In this regard, comparative historical studies on the figure of the poet in various Indo-European cultures are useful, as they attest to how this role was markedly different from what the term “poet” conveys today. As Campanile perfectly summarizes, the poet “is the individual who masters the art of speech in all its possible purposes: that is, he is a priest, jurist, doctor, historian, enchanter, apologist of the aristocratic structure of Indo-European society, and the sole preserver of its most ancient traditions” ([

30], p. 29). This is also justified by the intensive training that the poet had to undergo to become a master of speech, training in which attention to language and the art of its codification were essential priorities, thus far removed from the modern notion of the poet as a free composer of verses. Inspiration was mystical, yet it guided the poet in the rigorous codification of the message into an elevated linguistic form, closely linked to τέχνη not only as art but also as “power” ([

31], p. 20). In other words, the poet is “the conservator and professional of speech: he is, by definition, competent in all domains where speech is, or is considered to be, operative” ([

30], p. 32).

A clear example of the technical nature of this role, which also highlights the importance attributed to language, is the comparison drawn between the poet and the carpenter or the weaver. It should be noted, considering the contemplative function of language, that the carpenter is invoked metaphorically for his ability to “construct” something meticulously, precisely, and functionally. This is because, in the Vedic contemplative exercise (

dhī), which represents the devotee’s aspiration toward the divine, the metaphor employed is precisely that of a chariot or vehicle, intended to “lead” the contemplator toward the divine realm or to deliver his prayers to the deity [

26,

28,

32]. The contemplator must “construct” this chariot through his thought, and to achieve this, his skill must be comparable to that of a carpenter ([

26], pp. 52–62). Thus, given the essential comparability between mastery in language and mastery in contemplation, the metaphor of the carpenter is dual in this context.

The term used in this instance is often derived from takṣa- or stoma-, but it is the former that is of particular interest. Although its etymological meaning is primarily connected to the concept of dividing (takṣati), it also denotes the quintessential act of the carpenter or artisan who “fashions” something. The reconstructed Indo-European root for this term is tetḱ- (cf. Avestan auui tāšti, Latin tēla, tēlum, or texō), and it is no coincidence that it also underpins the Greek τέχνη. The Greeks employed the concept of τέχνη in a manner strikingly similar to the Veda.

In ṚV 1.62.13 and ṚV 1.130.6, the crafting of prayers–contemplations (navyam atakṣad brahma hariyojanāya) is compared to the crafting of a chariot by an artisan (imāṃ te vācaṃ vasūyanta āyavo rathaṃ na dhīraḥ svapā atakṣiṣuḥ sumnāya tvām atakṣiṣuḥ). Furthermore, ṚV 3.38.1 emphasizes the focus and discipline required of the contemplator, likening it to that of a disciplined carpenter (abhi taṣṭevadīdhayā manīṣām atyo na vājī sudhuro jihānaḥ). Similar observations appear in ṚV 5.2.11 (etaṃ te stomaṃ tuvijāta vipro rathaṃ na dhīraḥ svapā atakṣam), ṚV 5.73.10 (imā brahmāṇi vardhanāśvibhyāṃ santu śaṃtamā yā takṣāma rathāṃ ivāvocāma bṛhan namaḥ), ṚV 10.39.14 (etaṃ vāṃ stomam aśvināv akarmātakṣāma bhṛgavo na ratham), and ṚV 10.80.7 (agnaye brahma… tatakṣur).

As Campanile points out, terms connected to the root *

tetḱ- are also used in the Greek world to denote the same “poetic” action through the metaphor of the carpenter. In the

Pythian Odes, Pindar refers to poets as τέκτονες σοφοί ([

30], p. 35), Sophocles even defines the Muse as “chief carpenter” (τεκτόναρχος μοῦσα, ἀλλ᾽ οὐδὲ μὲν δὴ κάνθαρος τῶν αἰτναίων). Furthermore, in Ἑλλάδος Περιήγησις (10.5.1), we read τεκτάνατ’ἀοιδάν, an exhortation to craft songs as carpenters would, a comparison that, according to Campanile, arises from the technical nature of both the poet and the carpenter: “which does not tolerate individual fantasies, and which holds a significant and precise social function. A well-constructed song is akin to a cart that the carpenter can only build by repeating and preserving a form of knowledge far older than himself” ([

30], p. 36). The same applies to the comparison with a weaver (ṚV 5.29.15 as well

8, as the contemplation likened to weaving in ṚV 1.61.8 and 2.28.5), reflecting analogous operative methods of ποιητικὴ τέχνη. Even the

Iliad (3.212) employs an expression involving weaving (ὕφαινον) in reference to narratives (μύθοι), thus again to language (ἀλλ᾽ ὅτε δὴ μύθους καὶ μήδεα πᾶσιν ὕφαινον).

It should also be noted that Buddhism employs these metaphors in the specific context of contemplative practice: “just as irrigators guide water, fletchers shape arrows, and carpenters plane timber, those who are virtuous tame themselves” (

udakañhi nayanti nettikā, usukārā namayanti tejanaṃ; dāruṃ namayanti tacchakā, attānaṃ damayanti subbatā, Dhp 145). This notion of taming the self, where the term

attā is used for self, is particularly interesting, especially considering the philosophy of

anattā in Buddhism, which is markedly anti-Upaniṣadic and thus does not seem to be invoked here coincidentally. The carpenter also appears in AN 7.72, in a

sutta titled

Bhāvanā, a term that literally signifies growth but is, practically, a technical term for contemplative practice. Other mentions related to contemplation can be found in MN 20: cognition must become internally stilled, settle, and reach a unified state—a state of perfect immersion, akin to a carpenter or his apprentice carefully extracting a large peg with a finer one

9. Perhaps the most notable and interesting mentions, however, are in MN 10 and DN 22, the two

satipaṭṭhānasuttas. Here, the carpenter (and his apprentice) is again evoked in relation to meditation, but in the context of mindful attention. Just as a carpenter must focus keenly while cutting a mark and be present in the act of “cutting deeply or shallowly”, so too the meditator brings their present attention to the four

satipaṭṭhānas (

kāya, vedanā, citta, dhamma) with the same kind of awareness [

33]

10.

Faced with these exercises and these metaphors, the hypothesis under consideration is that, at least in the Buddhist context, such exercises were intended to function as anti-inhibitory processes; that is, to counteract the automatism [

34,

35,

36] generally associated with the act of naming. It may seem counterintuitive to combat automatism with another automatism, but it is crucial to first understand the nature of habituation constituted by the nominal function in the Buddhist sense, and secondly, the difference between inhibitory automatism and the “conscious” or attentive discipline enacted by Buddhist contemplative practice ([

33], pp. 10–11), [

37,

38,

39].

4. The Inhibitory–Habitual Process of the Nāma

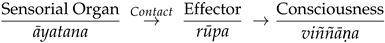

Under normal conditions, our body receives a certain number of environmental stimuli that are processed as sensory data. Sensation, even in the Buddhist system, constitutes the first level of processing. Sensory stimuli can be understood in various ways, but when considering them as organs capable of interacting in a particular manner with our sensory capacity, the dynamic between effector and sensor described by Uexküll [

40,

41,

42] remains one of the most effective models for representing the relationship between

rūpa and

āyatana in the Buddhist system.

For Uexküll, each animal essentially experiences its own environment, as the perceptual markers populating it function as signs with a specific semiotic value for each animal, which may not hold the same value (or any value) for others.

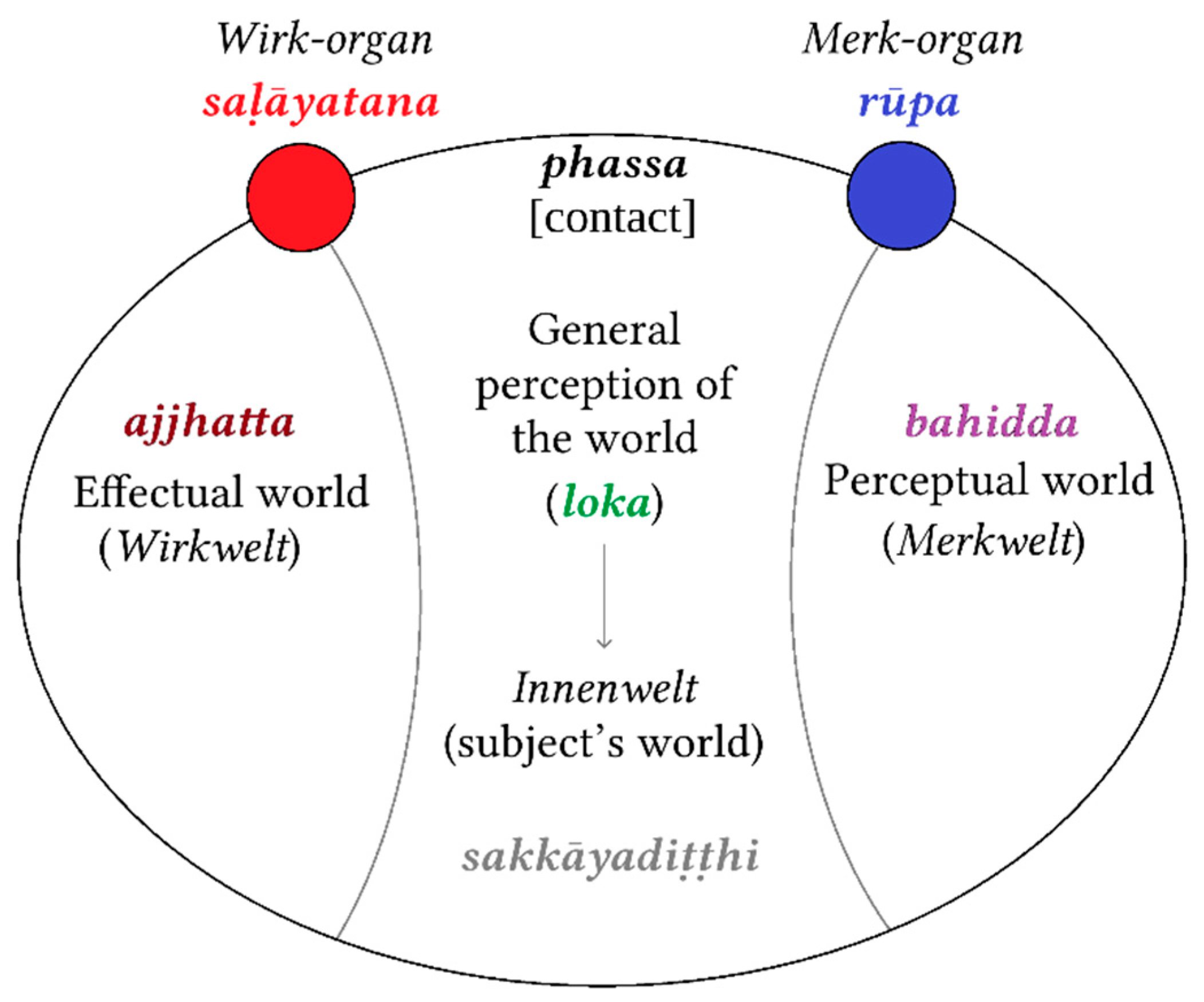

What emerges in

Figure 1 is a dynamic of constructing the experience of the world as an environment (

Umwelt), which can be recognized as having two fundamental interacting dimensions: the “perceptual environment” (

Merkwelt)—that is, how it is perceived by the organism—and the “effectual environment” (

Wirkwelt), comprising the modifications produced in the environment by the organism’s actions. The

Merkwelt is not “external” in an absolute sense; rather, it is that aspect of perceptual experience determined by the effectual organs. If the

Merkwelt is responsible for perception (stimuli registered and interpreted by the animal), the effectors in the

Wirkwelt are responsible for the animal’s active responses, such as movement or other actions that impact the external world.

I have identified in this dynamic the binomial relationship between

ajjhatta and

bahiddha, as Buddhism also recognizes the “external” world (

bahiddha) not as an autonomous and self-sufficient dimension but rather as the locus of perceptions. The internal (

ajjhatta), on the other hand, is specifically understood as the sensory spheres (

āyatana), as demonstrated by Qian Lin ([

43], pp. 343–348).

In my interpretation, as I will elaborate as we progress with this analysis, the Buddhist “world” (loka) should be understood strictly as a psycho-ecological dimension. This, which partially coincides with the Umwelt but does not fully align with Uexküll’s conception, is also responsible for that “sense of self” that Buddhists describe in the analysis of the five aggregates and the perception of natural identities. It is a complex construct, yet one that depends on the world (loka), exists in the world, and is of the world.

The contact (phassa) between an effector organ and a sensor is, in the system of the five aggregates, the starting point of the basic perceptual dynamic. The initiation of the process has rūpa as its apex, but it is important to emphasize that this term does not merely indicate a geometric form but rather a form cognitively apprehended through phassa. It is the initial datum susceptible to future elaborations, so much so that the system of the khandhas can be understood as a set of concentric nuclei: rūpa is the central element, around which the other aggregates layer themselves, dependent on the preceding state, around which they crystallize, and so forth. Moreover, there are multiple ways of understanding rūpa, just as there are various analyses of the perceptual process. The model of the five khandhas is extremely effective yet also nuclear, and it serves as the prototype for both the analysis of phenomenal processes and cognitive processes, which are, in reality, two aspects sharing the same nature. However, it is through the more in-depth analysis of factors like the nāma that the cognitive aspects will be examined in greater detail.

The principle of the five

khandhas applies to any construct, from one’s self to the identity of a supposed “external thing”, such as a “tree”. As is well known, the teaching of the five aggregates focuses primarily on the interdependent nature of all phenomena, thereby refuting the belief that they are autonomous and self-sufficient: their close interrelation is also to be understood as mutual implication. Hence, the artificial division we may draw between phenomenon A and phenomenon B arises for reasons extraneous to the actual nature of phenomena. The construction of a given conception, such as the separateness of phenomena A and B, depends on the conviction that phenomena A and B are defined by autonomous entities inherent to their nature and that refer to an essence of A as A and of B as B, which is independent and self-existent

11. Sensation (

vedanā), constituted by the first level of apprehension of experiential data, is insufficient in itself to construct this conviction. Sensations, in fact, are undifferentiated in their raw data state: even recognizing “smooth”, “rough”, “hot”, or “cold” is a subsequent attribution of identity that reorganizes the bundle of sensations and fragments it from a complex continuum into a series of recognizable entities structured according to highly generic prototypes. It must not be naively assumed that a sensation of smoothness is always identical. Certainly, touching the surface of a book cover and then a wooden piece of furniture may lead us to classify both as “smooth”, yet it is evident that this is a generalization and that there are an infinite number of differences between the smoothness of the book and that of the furniture. Sensations must, therefore, be organized in a particular way, and the function tasked with this role is called “perception” (

saññā). This function will also be encountered in the description of the cognitive apprehension of

nāma, which will become central later on.

Figuratively speaking, every animal subject attacks its objects in a pincer movement—with one perceptive and one effective arm. With the first, it imparts each object a perception mark [Merkmal] and with the second an effect mark. Certain qualities of the object become thereby carriers of perception marks and others carriers of effect marks. Since all qualities of an object are connected with each other through the structure of the object, the qualities affected by the effect mark must exert their influence through the object upon the qualities that are carriers of the perception mark and have a transformative effect on the perception mark itself. One can best sum this up this way: The effect mark extinguishes the perception mark.

Perceptions represent a further stage of organized conceptualization. Perception already imparts a level of “sense”, and indeed, as has been argued in other works, [

33,

44,

45,

46], “perception” in Early Buddhism can be defined as

psychosemantic, a force already of a semantic nature. Sensation, perception, and cognitive constructs (

saṅkhāra) form part of a subgroup within the five aggregates defined as “cognitive factors” (

cetasika). It is therefore plausible that the notion of

saṅkhāra is associative in nature.

In the constitution of a given percept x (associated with one or more sensations that must confer recognizability at the moment of experience), it is necessary to associate specific factual “possibilities”. These possibilities are the qualities of the percept as it has been constituted, and they form a set of ideas, specific “constructs” (

saṅkhāra). For example, considering that this system operates a priori—anticipating an acquisition, so to speak, of “immediate” sensory data while mediating them through cognitive associations—it resembles the perception of an object we identify as a “tree”: the apprehension of a series of sensations through

phassa (contact) between the sensory organs and environmental stimuli is qualified into an indeterminate number of elements rendered recognizable by our mental associations. This phase permits sensations, now “qualified” in a certain way, to be reconciled with the cognitive form that was previously learned [

47,

48,

49,

50].

Out of the infinite possibilities for a phenomenon like “tree” to manifest, someone who possesses the notion of “tree” identifies a common denominator among these differences. It is evident that no two “trees” are perfectly identical, yet the observer classifies them all as “trees”. This is due to the processing of sensory data that the observer has learned to associate with the idealized phenomenon, which is transformed into a cognitive prototype of experience. This process does not occur solely and trivially through sight. If one closes their eyes and begins to touch the trunk of a tree, it will not take long before the sensations of roughness and woodiness are associated with the same phenomenon. Smells, too, can serve this purpose. Most of us could recognize the taste of a familiar food even without seeing it, merely by tasting it. The principle is the same.

At this point, psychosemantic association intervenes: this is where sign perception comes into play, organizing perceptions and presenting a “tree” to the conscious mind. The phase of association with eidetic constructs is always linked to cognitive factors, but it serves a practical purpose: once the object “tree” is recognized, a series of multiple eidetic elements qualifying its possibilities also presents itself. A carpenter, for instance, will see in the tree a “raw material”, valuable “wood”; this is one possibility. A child might see in it the possibility of a game involving climbing its branches. Someone else might see shade, and thus coolness and shelter from the scorching sun or from rain.

In this framework, Buddhists have described with remarkable precision the “semiological” process of sign recognition, a fundamental psychological (indeed, psychosemantic) principle [

33]. This principle is integral to the invaluable reflections of Ferdinand de Saussure, which underpin modern linguistics, and it bears more than a coincidental resemblance to these Buddhist insights.

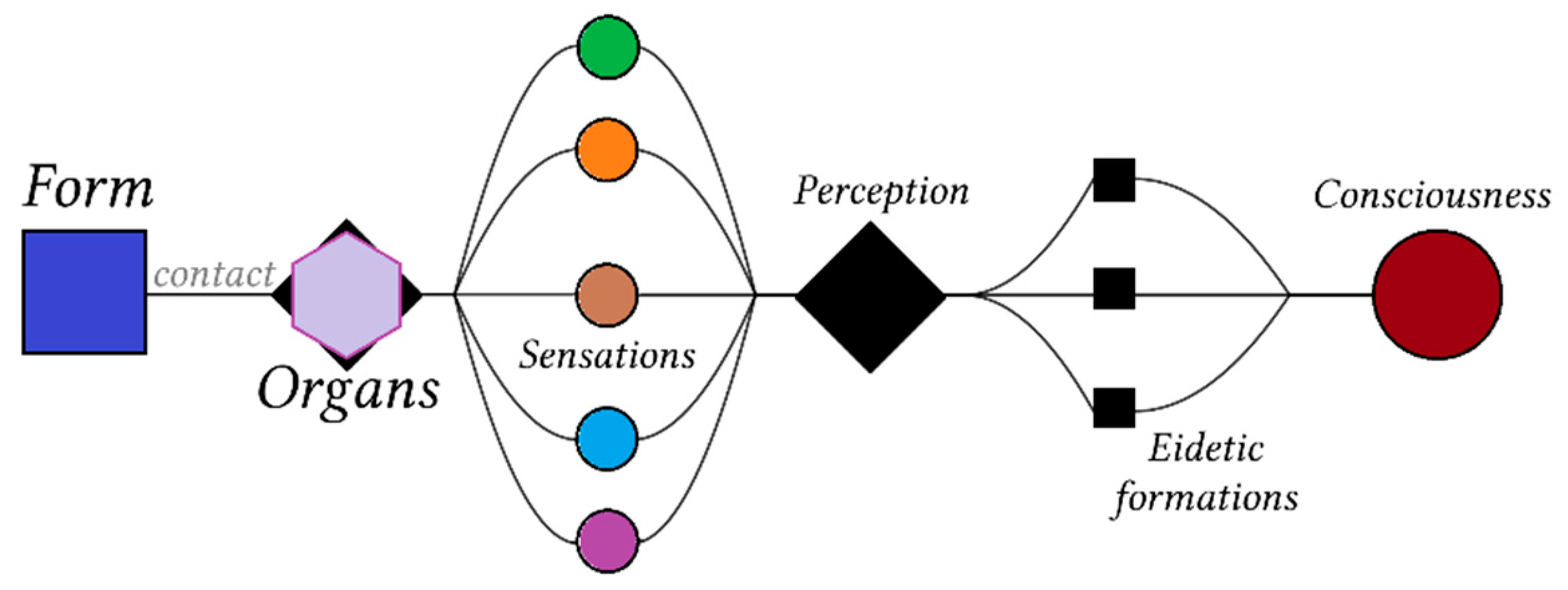

We know that each aggregate “links” to the previous one through a process of associations, thereby implying not only the immediately preceding aggregate but potentially all the aggregates preceding the one to which it is linked. Additionally, we know that the aggregates are functions that can be either simple or complex. Sensations (

vedanā), for instance, are depicted as plural because they are processed by the six sensory spheres (

āyatana), and thus, we can usually expect at least more than one sensation to be involved. For this reason, in

Figure 2, I have represented the first aggregate as, in reality, dual: the contact (

phassa) between form (

rūpa) and the sensory spheres (represented as a hexagon because Buddhists include thought,

manas, as the sixth sense).

By way of example, I have imagined the branching of five vedanā as associations arising from this initial form–sense contact, though there could also be fewer. For instance, in perceiving the aggregate “flower”, I will receive a series of visual sensations (the flower’s color and shape), olfactory sensations (its fragrance), and tactile sensations (if I hold it in my hand), but no auditory sensations unless I intentionally rub the flower near my ear to hear the sounds it produces.

I have represented perception as singular because

saññā, as a process of

synthesis (in the etymological sense of the term: indeed, σύνθεσις is related to putting together, σύν-; similarly, the term

saññā is composed of

saṃ- + √

ñā, ([

51], p. 1133), indicates a synthetic–associative type of knowledge that “brings together” all perceptions to associate them with a well-defined “sign’: “flower”).

Mental constructs (saṅkhāra) revert to being plural because the possible eidetic and volitional associations are multiple: the flower can be picked, trampled, observed, and so on. All these various possibilities are “volitions” branching out from ideas associated with that specific percept.

I will now proceed to conclude our analysis of the five aggregates before proceeding to the specific examination of

nāma. At this point, only one element remains to be addressed: consciousness (

viññāna). The importance of this term in early Buddhism is immense. Consciousness must be defined in its specific sense to avoid confusion with our preconceived ideas [

4,

52,

53,

54,

55]. First and foremost,

viññāna has a privileged relationship with

nāma. These two functions mutually imply one another; that is, each is responsible for the functioning of the other. This peculiar relationship of mutual generation and co-implication is specific to the

nāma-

viññāna axis, but it also clarifies certain functions of consciousness as such, which we will examine later.

Secondly,

viññāna is also part of another cycle—that of the five aggregates themselves (see

Figure 2). These aggregates are not to be understood merely as a stratification process of concepts “usable” by an individual; rather, they form a cyclical system without a clear origin. One of the functions of

viññāna, explicitly revealed by its etymology, which is sufficiently transparent in this sense, is to “separate” and “organize by dividing.” The form of knowledge (

ñāna, <

jñāna) managed by consciousness is primarily divisive in nature (

vi-, <

dvi-) ([

51], p. 961).

Let us return for a moment to the beginning of the process of the five aggregates: from a complex continuum of sensory stimuli, the perceptual–cognitive system “isolates” certain sensations to reduce them to specific and recognizable percepts. This divisive process constitutes the act of discernment, which is concretely enacted by consciousness. To understand rūpa in only one way would be incorrect in light of the Pāli texts, where the meanings of rūpa are manifold. Two, in particular, are of interest here: “form” can be understood both as an undifferentiated formal datum, aspectual and indicative of a specific epiphenomenology, and as a “recognizable” and “recognized” form by a cognitive system. At this point, “form” is no longer merely the aspectuality of a phenomenon—an undeniable part of the phenomenology of the world we observe, which does not necessarily imply independence, separateness, or isolation between formal aspect A and formal aspect B that follows it temporally or spatially (e.g., the form of seed A appearing first, then that of sprout B). Instead, it becomes an in vitro form, a functional prototype to which a whole series of similar but not identical phenomena can be referred, phenomena that must nonetheless be organized by isolating cognitions.

With this necessary premise established, the remaining aspect of

viññāna to consider is its “organizational” function, which is predominant. Certainly, the organization carried out by

viññāna is primarily based on divisions. However, having established this, it becomes clearer how a “system of knowledge” functions within Buddhist theory. The theory of knowledge involves methodically organizing a series of discrete “notions”

12.

The “world” that results from this operation is exclusively experiential in nature. It must be noted that, for Buddhists, the concept of “world” refers solely to this [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

53,

56]. To speak of a reality independent of these constructs and re-elaborations means engaging with a different level of knowledge, and “truth” (

sacca), understood as that which “is” (

sat-) in its most genuine sense, is neither an “other world” nor something reducible to mundanity. On the contrary, mundane realities appear as reductions in truth, and while they are not outside of it, they do not coincide with it perfectly.

This also explains the etymological nuance of the term

loka (“world”) and of related terms derived from the same root, such as the verb

oloketi, which means “to look at”, “to examine”, or “to look down (at)”. The reconstructed Indo-European root *

leu̯k- relates to shining, and to light, which elucidates its fundamental etymological significance. Light is obviously an instrument to clarify something that would otherwise remain unrecognizable. Light has always served as the quintessential metaphor for phenomena. A phenomenon is that which reveals itself in the light, becoming available to our perception and thereby comprehensible. In the Vedic world, however, this term also denoted an “open space”, as reflected in Old English

lēah (“open field, meadow”) or Lithuanian

laũkas (“field”). The meaning of “open space”, particularly “free”, is primary, followed by those of “world”, “realm”, or a collective of people organized into a society, “inhabitants [of the world]”. All these meanings, including the one linking this root to perception (cf.

oloketi) ([

46], p. 71) to the concept of perception or vision (cf.

locate and

locana), [(49], p. 907), ([

52], p. 79) are far from being in conflict with one another. The “open” (that is, “available”) space serves as a metaphor not only for the primordial conquest performed by the Vedic warrior–hero in the original establishment of the world—making the Earth, previously free from human dominion ([

57], p. 230], available—but also reflects the expulsion of darkness by Agni, who, in Vedic myth, emerges from the primordial waters to dispel the darkness [

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. The mechanism is the same: Agni, as the bearer of light, makes previously uninhabitable lands “knowable” [

65]. By casting light upon them, Agni not only makes them knowable but also “available” for human dominion, as these lands are, through the harnessing of fire’s power (

agniyojana) [

66], “conquered” and “known” by humans. However, the resulting “world” is merely the specific portion, the “field”, within which this perceptual–cognitive dominion operates and within which the organization of norms takes effect. This inevitably leaves an “other”, apparently outside these boundaries. Yet even when this “other” is conceptually reintegrated as a possibility within the normative structure—via the mechanism of anomie, the non-normed, the otherness, the beyond “unknown’—it remains, in every sense, “untilled land”. This metaphor, which is already Indo-European, is found, for example, in Ovid (as

tellus inarata) and in the

Uttarakāṇḍa (

akṛṣṭapacyā pṛthivī) ([

67], p. 211).

Much thought has been given to Buddhist asceticism. As is well known, one of the most prominent aspects of ascetic discipline is precisely the aim of exiting the “world” (the “field”, the “boundaries” of organized society), and the reasons for this exit can be manifold. For one, the normative order that would otherwise act as a coercive force on subjectivities is absent, which significantly facilitates a contemplative practice aimed precisely at disengaging from everyday habits. Here, we arrive at the fundamental crux of the matter, reconnecting with the problem of naming, and beyond.

The outcome of this intricate network of perceptual–cognitive processes can be summarized in one of the existential dramas characteristic of Early Buddhism, aptly captured by a formula found in Snp 4.13: “When a person sees, they see nothing but name-and-form; and having seen this, they will know only in this way” (passaṃ naro dakkhati nāmarūpaṃ, disvāna vā ñassati tānimeva). This passage is highly significant, as it introduces us to one of the fundamental dyads of Early Buddhism, arguably the cornerstone of early Buddhist psychology. The term nāmarūpa connects the concept of “name” with that of “form”, as we have delineated thus far. It is often translated as “name-and-form”, but since it is a dyad endowed with properties that operate only in the interplay of its two components, I will henceforth refer to it as n/r.

This passage establishes a connection between the act of seeing, expressed in two different ways:

passaṃ and

dakkhati. The former verb genuinely means “to observe” (Sanskrit

paśyati, derived from

speḱ-, vaguely implying “to inspect” or “to observe attentively”) ([

51], p. 611) and seems to alternate with

dakkhati, which is instead related to

dṛś, “to look something” (< *

derḱ-) ([

51], p. 491). However, it must be noted that it is likely the context that clarifies the specific nuance in this case. There is, in fact, an ingenuous, spontaneous observation defined by

passaṃ, and one conditioned by the factor

n/r. Moreover,

dakkhati does not merely mean “to observe” but also “to find something as a result of observation”. The observer of Snp 4.13 “realizes” that in the act of observation, they find nothing but

n/r. But what does this mean? Clearly, the

n/r dyad acts as a factor capable of conditioning ordinary lived experience, though it remains implicit, not overtly manifest. Nevertheless, upon more careful observation, it becomes evident that “everything” that seems to be “seen” is, in reality,

n/r.

Finally, the verse connects the pervasive action of n/r to knowledge: “Having seen this, they will know [only] in this way”. The key term here is tānimeva, “only in this way”, which evidently refers to the modality governed by n/r—a factor capable of conditioning the way of knowing. The seer who “having seen” (disvāna) only through n/r will consequently “know” (ñassati) only “in this way”, that is, through n/r.

It is crucial to emphasize this point, as it prompts reflection on the quasi-obstructive nature of n/r, an element that interposes itself like lenses between the eyes and what is seen. It also becomes evident that, in this passage, the sutta does not refer to the continuous sense of rūpa—firstly because it forms part of a compound—but at this juncture, it is legitimate to ask whether the rūpa that forms part of the n/r dyad differs from the rūpa that begins the chain of the five aggregates. If so, we must inquire into the nature of this difference. For now, I will preemptively state that the n/r dyad has a peculiar relationship with consciousness. Furthermore, of the two elements composing it, it is nāma that serves as the principal driver of its functions, and I will explain why.

5. The Functions of the Cognitive Binomial n/r

The cognitive binomial

n/r constitutes a semiosic coordination of perceptions [

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73]. Within this dyad, the term

rūpa refers not only to the cognitive form—a definition that can be broadly applied to the term—but also to its physical or material aspect. Additionally,

rūpa signifies the body, and as defined in the canonical texts, within the pair

n/r,

rūpa primarily denotes the four great elements (

mahābhūtā). This distinction, which we may loosely summarize as psycho/somatic or psychological/physical, should not mislead us. Buddhism does not endorse a real separation between the psychic and physical dimensions, just as the internal/external (

ajjhatta/bahiddhā) binary is evoked for practical purposes but is critically deconstructed in contemplative practice. While the distinction between the internal (psychological) and the external (physical) may have practical utility, at a deeper level, this binary must be abandoned.

avijjānīvaraṇassa, bhikkhave, bālassa taṇhāya sampayuttassa evamayaṃ kāyo samudāgato. eti ayañceva kāyo bahiddhā ca nāmarūpaṃ, itthetaṃ dvayaṃ, dvayaṃ paṭicca phasso saḷevāyatanāni, yehi phuṭṭho bālo sukhadukkhaṃ paṭisaṃvedayati etesaṃ vā aññatarena.

O mendicants, for a fool who is dominated by ignorance and bound by attachment, his body has been produced. There is thus a dualism between such a body and an external name-and-form. Contact depends on this dualism. When contact occurs between one or the other of the six sensory spheres [and the object of the senses], the fool thereby experiences pleasure and pain.

(SN 12.19)

The reason is not that the internal and external do not exist, but that they are not closed, independent dimensions; rather, they are two parts of a continuum. Consequently, their invocation serves functional purposes, as in the case of MN 28, but it is quite evident that these categories are conceptual fictions.

For example, MN 28 states: “Though the eye is intact internally, so long as exterior sights do not come into range and there is no corresponding engagement, there is no manifestation of the corresponding type of consciousness” (

ajjhattikañceva cakkhuṃ aparibhinnaṃ hoti, bāhirā ca rūpā na āpāthaṃ āgacchanti, no ca tajjo samannāhāro hoti, neva tāva tajjassa viññāṇabhāgassa pātubhāvo hoti). This refers to a classical model of Early Buddhist psychology, for which any sensorial organ produces its own consciousness when it enters

into contact with a specific form. For example,

This model can be translated concretely into the processual development of any consciousness, such as “visual consciousness” (cakkhuviññāṇa), that arises from the contact (phassa) between the āyatana of vision, i.e., the eye (cakkhu), and the visual form.

Another significant example is found in MN 109, which addresses the origin of the five aggregates: “Sir, how can one know and see that there is no formation of “I”, no underlying tendency that substantiates this perceiving body and all the external stimuli [lit. “external signs’]?” (‘kathaṃ pana, bhante, jānato kathaṃ passato imasmiñca saviññāṇake kāye bahiddhā ca sabbanimittesu ahaṅkāramamaṅkāramānānusayā na hontī’ti).

Thus, beyond their practical significance—which frames the ajjhatta/bahiddhā pair as a relationship between sensor and effector—it must be noted that this dyad also accurately describes the phenomenological mechanism of the appearance of the five aggregates. It is important to understand that any given phenomenon x, such as the formation of the psychological self (ahaṅkāra), involves the five aggregates as fundamental elements that are simultaneously present within the phenomenon, interconnected and interacting. The phenomenon called ahaṅkāra is composed of at least five simpler categories of phenomena, which, in their aggregation, enable its manifestation—much like a house of cards.

What is particularly noteworthy about MN 109 is the type of relationship it establishes between the last of the five aggregates (viññāṇa) and the n/r pair. It states that the n/r pair constitutes the phenomenal condition for the arising of consciousness (nāmarūpaṃ kho… hetu, nāmarūpaṃ paccayo viññāṇakkhandhassa paññāpanāyā). This is intriguing because it does not refer merely to form, as the first aggregate does, and thus it does not allude to the cyclical structure we examined in the preceding section. Another important sutta that establishes a relation between the n/r dyad and consciousness is SN 12.64, in which we read that the two entities are related by a process of phenomenological appearing (avakkanti) and development (patiṭṭhitaṃ). For instance, it is said that “once consciousness is established and developed, there is the appearing of n/r” (attha patiṭṭhitaṃ viññāṇaṃ virūḷhaṃ, atthi tattha nāmarūpassa avakkanti).

It remains true that consciousness, in its role as an element discerning the sensible reality, segments “forms” into recognizable cognitive prototypes, thereby perpetuating the circular nature of the five aggregates. From the apprehension of a given form as a cognitive datum, the mechanism proceeds with the elaboration of sensations, their association with fundamental percepts, the correlation of these percepts with related eidetic constructs, and thus their relationship with consciousness. From here, the cycle continues: consciousness will preferentially recognize, in its explored environment, those same forms that align with prototypical cognitive models. Consequently, consciousness continues to act as an agent that “segments” the formal phenomenological continuum into individual, discrete phenomena that can be cognitively isolated and thus apprehended as distinct “forms”.

This cycle involves two aspects of the concept of form: the original aspect of the phenomenological continuum and the discrete aspect of the learned cognitive form. However, it does not encompass the relational nexus between form and name that comprises the

n/r pair, in which the formal aspect must be understood as co-dependent with the nominal aspect [

43,

74,

75].

We better understand this problem when we see that MN 109 connects it to the conception of identity (

sakkāyadiṭṭhi) ([

51], p. 1134). To form the conception (the term

diṭṭhi is not used accidentally) of the autonomy of a given psychophysical entity (

sakkāya, from

sat-

kāya, the existence of a body), it is necessary for a particular element of a psychosemantic nature, such as the agent

n/r, to be perceived as something self-standing. Observing a certain entity in the world—a body not merely understood as an organism but anything that constitutes, in itself, an identity boundary in our perceptions—we realize that the perception of its autonomy, translated into an identity conception (

sakkāya), is derived precisely from its being an

n/r; that is, a certain formal givenness (

rūpa) associated with a nominal identity (

nāma). Of a certain formal continuum, we determine that, under certain conditions, some of those formal aspects, and not others, are to be considered autonomous. We then associate with that precise formality a given nominal identity, something that qualifies it as distinct from others.

In other words, “internal” refers to the subjective aspects of experience, namely, the six senses and their corresponding consciousnesses. Therefore, the six sense bases constitute the body (kāya), and the body is accompanied by or possessing (sa-) consciousness (vijñāna). “Externally”, meanwhile, are the objects of experience, which are names (nāman) and forms (rūpa), or more generally, “all signs (sarvanimitta)”. These can be further analyzed as being of six types, and are objective in the sense that they are not taken as part of the sentient being that is considered the subjective experiencer. This interpretation of internal and external as the subjective and objective aspects of experience can be further confirmed by the sūtras’ explicit references to the six sense bases (āyatana) as “internal” (ajjhattika), and to their respective objects as “external” (bāhira).

In this sense, the n/r dyad is the fundamental quality of any psychosemantic construct, from our self-perception of identity to that of an object such as a “vase”. The determining principle is the same, which is why MN 109 recognizes that the n/r dyad is the condition for the functioning of discernment (viññāṇakkhandha). My identity is defined by a series of qualities nominally attributed to me: from my registered name to my profession or education, my address, physical characteristics, and so forth. All these qualities, coordinated by specific names, are the various x, y, and z that define me: I “am” x, y, z. These qualities associate with my identity to define me by opposition. This, it should be noted, is their sole function: distinguishing who is x, y, z, from who “is not” x, y, z, and who may instead be a, b, c. The “vase” is not a “table”, and the “table” is not a “chair”, and so forth.

The issue, which for the Buddha is the core of this cognitive deception, lies in attributing ontological autonomy to these characteristics instead of recognizing them as epiphenomena that we have surreptitiously abstracted from a continuum, and which therefore remain inseparable from that fundamental complex web of relationships. This does not mean denying the differences in their aspects, but rather that these differences do not imply, as the human cognitive apparatus unconsciously seems to assume, autonomy in essence. Believing that a thing “is a self” means, in these Buddhist terms, believing that it is autonomous and self-sufficient; nothing more. And this is the true core of the problem: “they regard the form as self, as having a form, as self in form, or form in self” (rūpaṃ attato samanupassati rūpavantaṃ vā attānaṃ attani vā rūpaṃ rūpasmiṃ vā attānaṃ).

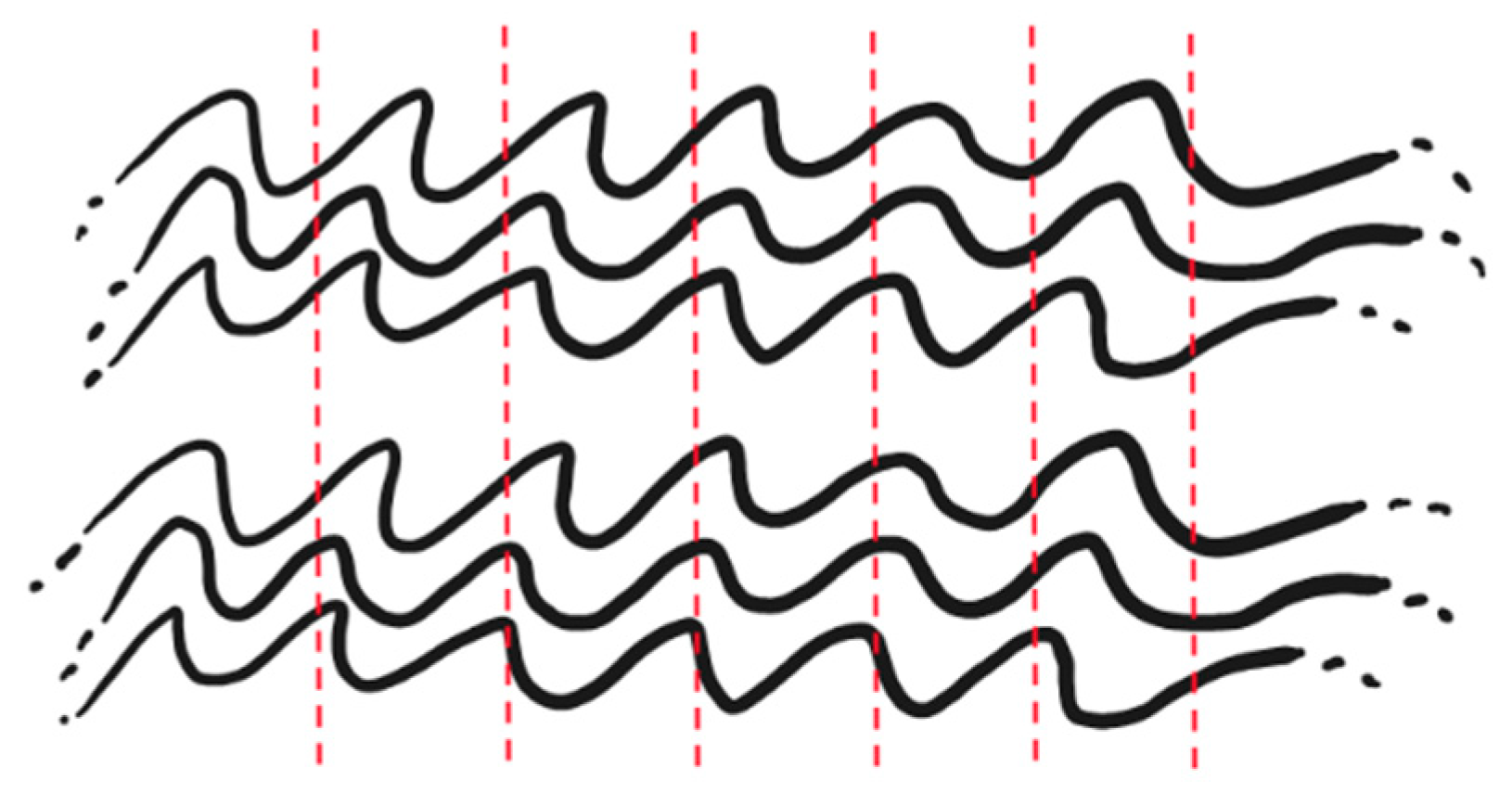

In this sense, nāma can be better understood as an inhibitory process that reduces cognitive responses to certain perceptual stimuli, systematically relating them to known determinations, to already acquired identities, and thus not experiencing perceptual stimuli as new but as part of a recognizable system. For this reason, we can say that nāma, heading the n/r dyad, is a process of habituation of perceptions. Habituation is any inhibitory process that progressively suppresses a response to certain recurring stimuli. Just as someone wearing a tight bracelet will, after a certain period, grow accustomed to the presence of that stimulus and no longer notice the bracelet, in our “world” (understood as loka, and thus especially as a network of incorporated sociocultural dynamics), the fundamental recurring stimuli are reiterated through systems of values conveyed by linguistic signs or ordered by them.

We somatically respond to certain conceptual stimuli, and just as we “conform” our body to certain stimuli automatically, other stimuli are inhibited in their novelty value because they are recognized as something familiar and manageable. In our psycholinguistical dimensions, the recurring stimuli acts as “signs”, and the Buddhist contemplative practice aims to attain a state of complete liberation from the influence of any sign; that is, a state of complete signlessness (

animitta) [

76,

77].

In the cultural world where the concept of the “president” has a certain value, the body of the individual holding the presidential office becomes an emitter of psychosemantic signals recognizable to other subjects for whom those particular signs hold a certain value. Conforming to those signals, our body reacts: it “bends”, it bows in deference. This is a mechanism far from merely theoretical but stimulates significant bodily reactions: it is the actualization of Hegel’s master–slave dynamic.

This is not even a uniquely human prerogative. In the world of bees, a body capable of emitting signals that hold value for some but not for others is, for instance, a flower. The bee can recognize the signs/signals of the flower as having value for it because it has a particular relationship with that body and thus recognizes its effectors. The flower, too, benefits from its relationship with the bee, constituting a functional circuit with it, as part of a shared ecological environment. A rock, as is evident, will not emit signals of the same value to the bee. Another example is described below:

We see the bees in their surroundings, a meadow in bloom, in which blossoming flowers alternate with closed buds. If one places the bees in their environment and transforms the blooms according to their shape into stars or crosses, the buds will take the form of circles. From this, the biological meaning of this newly discovered characteristic of the bees is effortlessly apparent. Only the blooms, not the buds, have meaning for the bees.

Habit prevents us from marveling each time certain values act in our daily lives. In the complexification of cognition that humans achieve through language, there is also the expectation that the world is populated by “things” and “names”; that is, by identities inherent to each thing. This expectation is so strong that even when we do not know the name of something, we are nonetheless certain that it possesses an identity, and we can assume “not knowing the name”; such is the conviction that the world is populated by “things” merely awaiting their appropriate labels. Thus, when we walk in the park and see a “flower” or a “tree”, we are not amazed: we are “accustomed” to these stimuli because we immediately associate them with known identities. Even if we were to encounter a flower we have never seen before, our astonishment would still be minimal: it would be a flower with an unknown name, but it is necessarily “something”.

This mechanism also operates as a function of conformity to specific sociocultural norms that are not questioned by the bodies assimilating them. The “king”, along with all the values connected to his figure, such as superiority over “lower classes” (“class” being another value—values, of course, exist within a network of relationships that define their interconnections), imposes his semiotic value with a force that is not contested by the “subject”, who has accepted the value of their social identity and conforms automatically, fulfilling their “social duties” without objection (see, for example, Snp 1.10, Snp 1.7 and variants found in Snp 3.9 and MN 98) ([

78], p. 152), ([

79], p. 178), ([

80], pp. 21–22), [

81,

82,

83,

84].

Although Buddhists give a decidedly unique characterization to the

n/r binomial, and their psychological conception of this factor’s functioning is undoubtedly part of their innovations, it should be noted that it is already mentioned in the Upaniṣadic world

13.

The n/r dyad produces yoking (see SN 12.58), chaining, “fettering” (saṃyojaniya), and possesses the nature of a bond. It can be understood in two ways: either it yokes the subject to its power, or it “binds” or “chains” itself to the subject to act. In both cases, the pervasiveness and invasiveness of its mechanism are unquestionable. The term saṃyojaniya also relates to obstruction in addition to chaining (fettering, bonding): n/r is an obstructive element to immediate perception. Furthermore, the n/r dyad is the phenomenal condition for the six sense organs (nāmarūpapaccayā saḷāyatanaṃ).

DN 14 emphasizes not only the relationship between n/r and the sensory spheres (‘nāmarūpe kho sati saḷāyatanaṃ hoti, nāmarūpapaccayā saḷāyatanan’ti) but also the direct connection between n/r and consciousness (‘nāmarūpe kho sati viññāṇaṃ hoti, nāmarūpapaccayā viññāṇan’ti), further relating the two phenomena (nāmarūpapaccayā viññāṇaṃ, viññāṇapaccayā nāmarūpaṃ, nāmarūpapaccayā saḷāyatanaṃ).

DN 15 elucidates the rationale for this interconnection. Here, it is explained that n/r serves as the condition both for consciousness and for sensory phenomena due to its pervasiveness in the relational nexus, i.e., in contact (phassa). On the other hand, its obstructive nature (saṃyojaniya) already suggests that n/r is the quintessential mediating element in experiential processes. DN 15 identifies n/r as the specific condition for contact (‘nāmarūpapaccayā phasso’ti iccassa vacanīyaṃ).

This signifies something crucial: Buddhists do not conceive of contact as a purely relational nexus, such as the interdependence of phenomena—the idea that every phenomenon is tightly interconnected with every other. Instead, contact is an apprehensive agency, a grasping in the Husserlian sense (

Erfassen), ([

85], pp. 14–15), and thus an act of relating to something after having cognitively isolated it beforehand, i.e., having conceived it as an autonomous phenomenal aggregation. For this reason,

n/r is a condition of

phassa, and the circle closes in the following two phrases, where the

n/r dyad is identified as being “conditioned” by consciousness itself (

viññāṇapaccayā nāmarūpaṃ).

This leads to an apparent paradox: mutual conditionality. The fundamental contact with form, which initiates the chain of the five aggregates, is evidently the contact with the sensory spheres (

saḷāyatana), as these are the only ones producing “sensation”. However, the sensory spheres are themselves conditioned by

n/r: “name-and-form is the condition for consciousness, consciousness is the condition for name-and-form; name-and-form is the condition for contact, contact is the condition for sensation” (

nāmarūpapaccayā viññāṇaṃ, viññāṇapaccayā nāmarūpaṃ, nāmarūpapaccayā phasso, phassapaccayā vedanā). We can observe several examples of this process in the Pāli canon. For instance, Iti 41 discusses a genuine form of habituation to

n/r, a condition in which this force is fully established (

niviṭṭhaṃ nāmarūpasmiṃ) and leads to the belief in absolute truths (

idaṃ saccanti maññati). Dhp 221 attributes to the

n/r dyad a nature connected to attachment

14, or at least suggests that attachment fuels the mechanism underlying it. The same is stated in SN 1.34 (

taṃ nāmarūpasmimasajjamānaṃ, akiñcanaṃ nānupatanti dukkhā) and SN 1.36 (

saṃyojanaṃ sabbamatikkameyya; taṃ nāmarūpasmimasajjamānaṃ…). DN 15 further informs us that name is something seen as possessing “features, attributes, signs, and details through which the aggregate of phenomena” allows what is called name to be recognized (

ākārehi yehi liṅgehi yehi nimittehi yehi uddesehi nāmakāyassa paññatti hoti). In the absence of these factors enabling the appearance of the nominal phenomenon, even form could not be found (

tesu ākāresu tesu liṅgesu tesu nimittesu tesu uddesesu asati api nu kho rūpakāye adhivacanasamphasso paññāyetha).

6. The n/r Dyad Is a Primary Semiosis Function

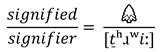

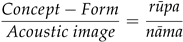

There are several reasons to hypothesize that Buddhists attribute the origin of the sensory spheres to the n/r dyad, but the most probable is the fact that the n/r dyad, being fundamental to consciousness, has a direct impact on the sensory spheres. This is because the sensory spheres are considered functional only insofar as they lead to the arising of their corresponding consciousness. Indeed, each of the six sensory spheres has its respective consciousness, which arises in relation to the contact between the sensory organ and the formal effector. Since every consciousness is solely a consciousness of something, and since the specific consciousness of an organ exists only in relation to its interaction with an effector, it follows that the consciousness of the sensory organs has merely a functional basis and does not represent a distinct entity: it is implicit in the functions of the sensory organ. For example, from the contact between the eye and a visual form arises visual consciousness; similarly, from the contact between the ear and an acoustic form—such as a sound or a given “acoustic image”, to use Saussure’s terminology (image acoustique)—arises a specific auditory consciousness suited to analyze it, and so forth.

Le caractère psychique de nos images acoustiques apparaît bien quand nous observons notre propre langage. Sans remuer les lèvres ni la langue, nous pouvons nous parler à nous-mêmes ou nous réciter mentalement une pièce de vers. C’est parce que les mots de la langue sont pour nous des images acoustiques qu’il faut éviter de parler des « phonèmes » dont ils sont composés.

Nonetheless, the suttas also highlight the merely semantic nature of the n/r dyad, and thus its grounding in a primarily linguistic function. This is not necessarily understood as articulated language, but as something upon which even articulated language is based: the essential processes of discernment and organization of entities in the world into “things” endowed with their specific “names”. For example, the nāma forms another dyad in MN 98, namely nāmagotta (name-clan). Belonging to a specific clan as a determining factor in an individual’s life is another of those mechanisms of attribution and designation to which the Buddha appeared particularly averse: “the householder cannot compete with the mendicant: the sage who meditates sheltered in the forest” (evaṃ gihī nānukaroti bhikkhuno, munino vivittassa vanamhi jhāyatoti, Snp 1.12). Countless sections of the canon attest to the Buddha’s strong rejection of the idea that family or “birth” (jāti) should determine an individual’s life (Snp 1.7), as is also evident in MN 98.

- samaññā hesā lokasmiṃ,

- nāmagottaṃ pakappitaṃ;

- sammuccā samudāgataṃ,

- tattha tattha pakappitaṃ.

- Merely by designation in the world,

- is the name-and-family conceived;

- Arise by virtue of common consensus,

- Thus conceived for everyone.

It appears evident that the name, at the head of the

n/r binomial, renders the latter essentially a semiosis device, much like consciousness, which primarily enacts the divisive aspect of semiosis; that is, the discernment between two signs perceived as distinct. Semiosis is the process through which a sign acquires a certain meaning and is perceptively interpreted by its recipient, thereby enabling communication and mutual understanding [

68,

72,

73]. In other words, it is the activity of producing, transmitting, and interpreting signs through which meaning is constructed and shared. The semiosis of division is also what makes the binomial

langue/

parole possible within the Saussurean framework. It must be noted that this distinction is primarily based on “psychic” facts (to use Saussure’s terminology)

15 that conform to historically established social and cultural networks.

La partie physique peut être écartée d’emblée. Quand nous entendons parler une langue que nous ignorons, nous percevons bien les sons, mais, par notre incompréhension, nous restons en dehors du fait social. La partie physique n’est pas non plus tout entière en jeu: le côté exécutif reste hors de cause, car l’exécution n’est jamais faite par la masse; elle est toujours le maître; nous l’appellerons la *parole*. C’est par le fonctionnement des facultés réceptive er coordinative que se forment chez les sujets parlants des empreintes qui arrivent à être sensiblement les mêmes chez tous. Comment faut-il se représenter ce produit social pour que la langue apparaisse parfaitement dégagée du reste? Si nous pouvons embrasser la somme des images verbales emmagasinées chez tous les individus, nous toucherions le lien social qui constitue la langue.

The first work to compare semiosis to the

n/r binomial was an article by Edward Small [

86], which engaged in a comparative dialogue with Saussure. However, Small argues that the

n/r binomial allows for epistemological possibilities that Saussure chose to ignore, despite his knowledge of Sanskrit. Today, we know that Small was partially mistaken: with the publication of Saussure’s unpublished writings [

87], we gain further insight into his conceptions, and many similarities between his thought and Buddhist philosophy acquire new significance. Certainly, Small correctly identifies the potential of the

n/r binomial, particularly in view of its mutual dependence with “the human sensorium”, which indicates a conception “that is neither positivist nor materialist but which rather suggests that signs are constitutive devices for cognitive-perceptual categorization” ([

86], p. 458).

Regarding the claim that Saussure ignored this literature, I am, however, skeptical. The publication of the Harvard manuscripts suggests the exact opposite ([

17], p. 79), and although these writings are disorganized, it is evident that Saussure’s passion transcended mere dialogue with Indian grammarians (where the concept of

nāmarūpa does not appear prominently). He was a conscious and attentive reader of Buddhist issues as well, and there is reason to suspect that a dualistic model (such as that of

nāmarūpa, though not necessarily confined to it) permeating all descriptions of cognitive deceptions as understood in Pāli Buddhism might underlie the antinomy between signifier and signified. Here, the signifier, which Saussure himself understands as a cognitively learned datum rather than a physical fact (physicality itself is relatively marginal to the interests of Saussurean “semiology”) ([

18], p. 81), ([

19], pp. 43–44), may be comparable to the idea of

nāma, understood as a nominal signifier paired with a given cognitive form (for Saussure, they are merely “faits de conscience” that determine the functional circuit underlying language) ([

18], pp. 76–77), a formal meaning (

rūpa) that, again, is understood as a specific cognitive prototype: the mental image of the ideal tree, which serves as the model to which the perception of every phenomenal tree is associated.

Le fond ou le tréfond de la réflexion hindoue sur les choses réside, à ce que je crois, dans l’idée de substance qui a dominé entièrement l’imagination de ces peuples, car une substance est à la fois ce qui développe des effets et ce qui reste inaltérable à travers les formes.

But the most interesting reflection that Saussure makes in the Harvard manuscripts concerns precisely the concept of identity as a psychosemantic obstruction:

Le procédé philosophique de l’esprit hindou est invariablement le même: 1° il écarte le monde, et les sensations qui en proviennent/2° il lui reste « l’intime » et il suppose que ce moi sans qualités ni affections possibles est identique à la substance universelle. Les différences ne sont que des variations sur ces deux thèmes, même quand elles aboutissent (beaucoup de ratures) à modifier un des 2 centres fondamentaux en niant absolument le moi, comme dans l’idée bouddhique, ou en multipliant les moi comme dans la philosophie sânkhya.

On pourrait caractériser comme suit le conflit fondamental entre l’Inde et notre pensée occidentale. Pour cette dernière la question s’est posée séculairement entre le moi, comprenant ses sensations, et le non-moi/et pour l’Inde, éternellement, entre le non-moi et le moi en excluant du moi les sensations elles-mêmes, comme non différentes de l’objet […].

It may not primarily assume the form of “conflict”, as Saussure notes in his writings, but it is certain that the conception of the psychological, as we have seen in the problem of

sakkāyadiṭṭhi—that of perceived psychological identities—is fundamentally a psychosemantic issue. In its critique of dualism and the semiosis of dividing, Buddhism emphasizes this central aspect: the division between perceiving subject and perceived object may hold practical utility, but it does not concretely reflect reality, which is rather a complex network of phenomena that are distinct yet not autonomous, differentiated yet not self-sufficient, characteristic yet not truly separate from one another

16.

This is the fundamental critique of perceptual dualism (ultimately extending into a critique of dualism, in general, as a system insufficient to account for phenomenological complexities). Beyond this theme, which is fascinating but merits separate treatment, Buddhists understand—and Saussure perceives—that the principle of divisive semiosis, namely a mechanism that organizes perceptions on a dualistic basis, underpins the construction of human “worlds”. This principle also applies to the

n/r binomial, which is a dualistic principle of biosemiotic systems. Saussure further identifies this level of complexity, speaking of “unceasing duality” in psycholinguistic systems ([

19], pp. 17–18). He views linguistics as a science closely related to psychology precisely because the principles of language essentially describe problems of a perceptual and cognitive nature.

In this sense, Saussure’s unpublished writings are extremely valuable to us, as they help better define the problem—one that Saussure clearly grasped—of the relationship between language and perception. In defining the actual object of linguistic study, he writes that the issue primarily concerns the constitution of “points of view” (

points de vue). Buddhists might refer to this as

diṭṭhi. The essence of this reflection is as follows: prior to language, it can be said that there are no determined points of view. At the same time, precisely because language determines “points of view” in the cognition of speakers, studying language while attempting to position oneself outside a point of view becomes a rather arduous endeavor ([

19], p. 19). The proximity of this reasoning to the same problems highlighted in Pāli Buddhism is, of course, striking—particularly in the suttas like Snp 4.3

17, Snp 4.9

18, or Snp 4.14

19, which critiques the problematic nature of adherence to any “point of view”. This is comparable to Saussure’s discussion of the indefinite referral of points of view: for instance, positioning oneself in a stance that seeks to exclude a certain point of view A means adopting another determined point of view, such as B, whose identity is defined by its intent to be non-A but which does not escape the problem itself. The issue persists as long as one seeks to define a science through the specification of names and concepts: “parler d’un objet,

nommer un objet, ce n’est pas autre chose que d’invoquer un point de vue A déterminé” ([

19], p. 23). Furthermore, Saussure continues, a given point of view A is equipped with its corresponding concepts/names, which have value only relative to the determined point of view A. Establishing a different order, B, would not resolve the problem but would merely create a different system based on the same functional principle.

One of the most comprehensive explanations of the nominal function is provided in MN 9. In this sutta, it is explicitly explained what is meant by nāmarūpa, and specifically how to understand nāma and rūpa. As previously mentioned, rūpa is essentially understood as cognitively apprehensible phenomenal possibilities. While it is not of primary interest in this context, it would certainly be relevant in a paper focused on the physical ontological conceptions of early Buddhism, given that such phenomenal aspects are substantially described through the model of the four elements (cattāri ca mahābhūtāni).

As for nāma, it is identified as consisting of five fundamental elements, three of which are also part of the five aggregates (technically two, since “contact” is implicitly considered part of the aggregates as it enables perceptual processes, but it is not included in the list beginning with rūpa). These constituents are sensation (vedanā), perception (saññā), intention (the term cetanā has a broad connotation of volition, but we must understand it more in the sense of the Latin intendō), contact, and attention (the term manasikāra also has a broad volitional connotation, but since it pertains to thought, manas, we can interpret it as a set of conceivable possibilities of the perceived “thing”, its “thinkabilities”).

- yato kho, āvuso, ariyasāvako nāmarūpañca pajānāti, nāmarūpa-samudayañca pajānāti, nāmarūpanirodhañca pajānāti, nāmarūpanirodhagāminiṃ paṭipadañca pajānāti—

- katamaṃ panāvuso, nāmarūpaṃ, katamo nāmarūpasamudayo, katamo nāmarūpanirodho, katamā nāmarūpanirodhagāminī paṭipadā?

- vedanā, saññā, cetanā, phasso, manasikāro—idaṃ vuccatāvuso, nāmaṃ;

- cattāri ca mahābhūtāni, catunnañca mahābhūtānaṃ upādāyarūpaṃ—idaṃ vuccatāvuso, rūpaṃ.

- iti idañca nāmaṃ idañca rūpaṃ—

- idaṃ vuccatāvuso, nāmarūpaṃ.

- viññāṇasamudayā nāmarūpasamudayo, viññāṇanirodhā nāmarūpanirodho, ayameva ariyo aṭṭhaṅgiko maggo nāmarūpanirodhagāminī paṭipadā, seyyathidaṃ—

- A noble disciple perfectly understands what names and forms are, what their origin is, their cessation, and what practices lead to their cessation. But what are name and form? What is their origin, their cessation, and the practice that leads to their cessation?

- Sensation, perception, intention, contact, and attention;

- This is called “name”;

- The four primary elements and the form derived from the four primary elements;

- This is called “form”.

- Thus, this is name and this is form.

- This (together) is called name-and-form.

- Name and form arise from consciousness. Name and form cease when consciousness ceases. The practice leading to the cessation of name and form is simply the noble eightfold path.

(MN 9)

Apart from reiterating the mutual dependence of the