A Protocol for the Biomechanical Evaluation of the Types of Setting Motions in Volleyball Based on Kinematics and Muscle Synergies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Design

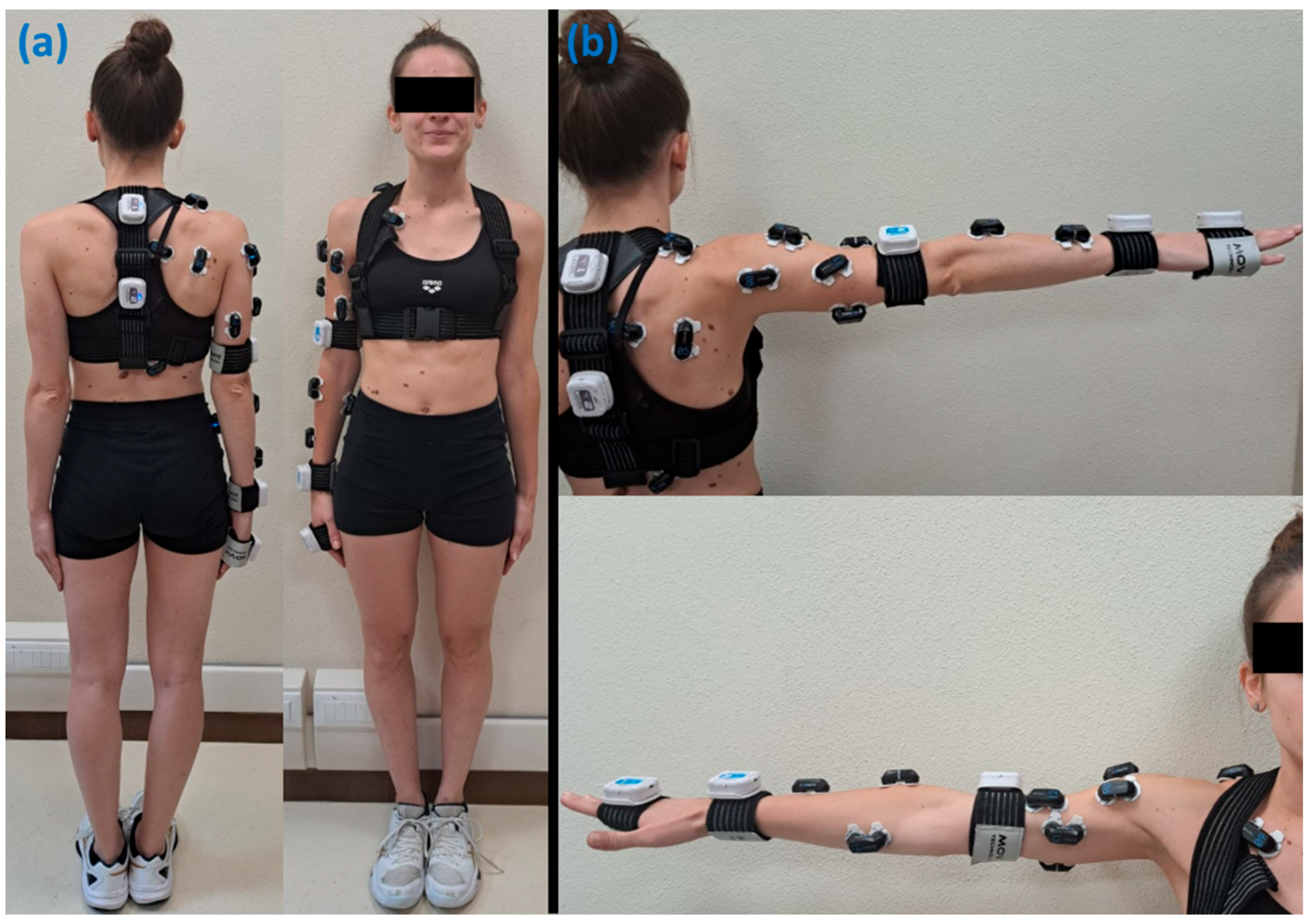

2.1. Equipment and Sensors Positioning

2.2. Data Acquisition

3. Procedure

3.1. Experimental Protocol

3.2. Kinematics

3.3. EMG Pre-Processing and Muscle Synergies Extraction

3.4. Test–Retest

4. Results

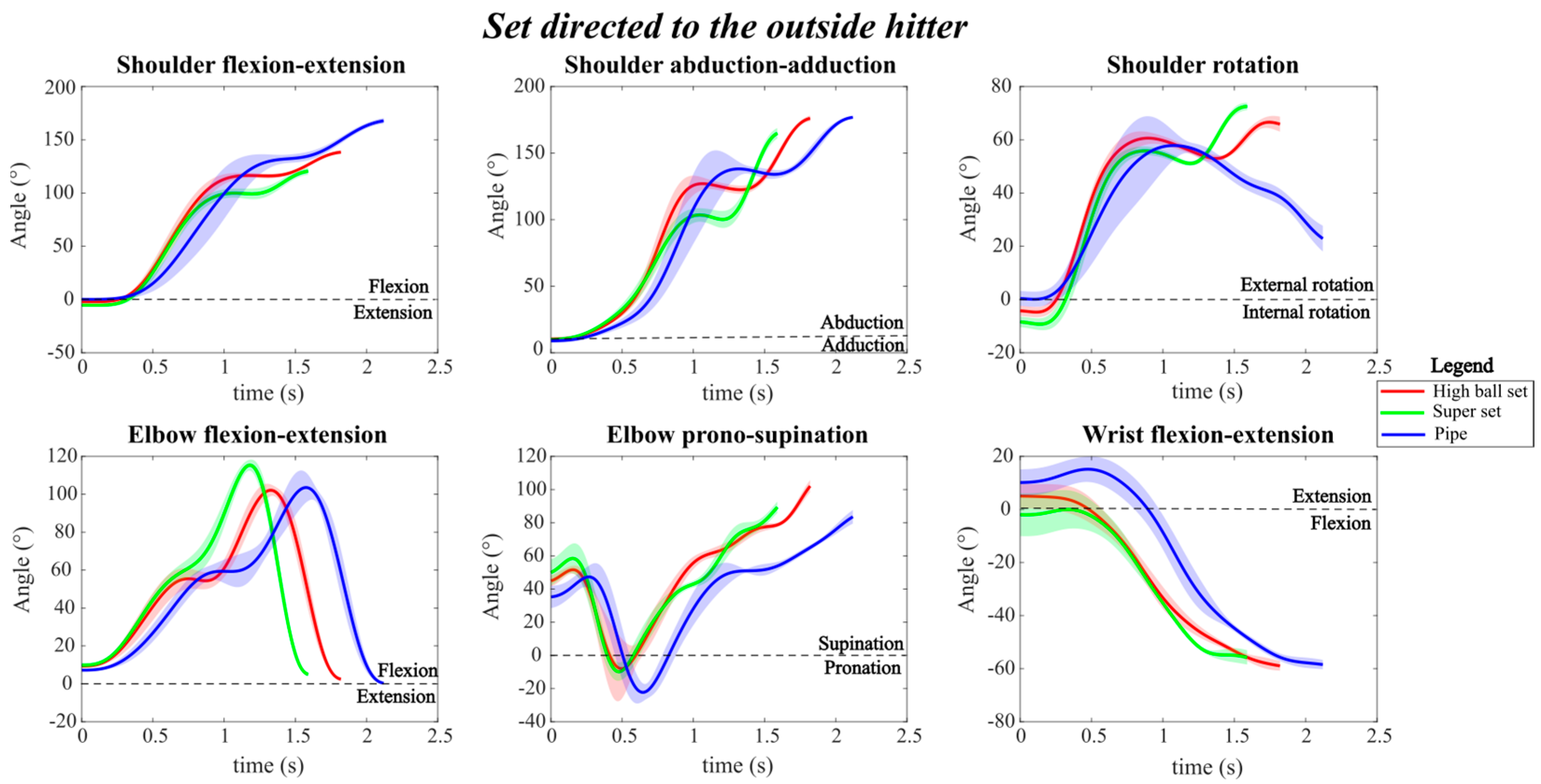

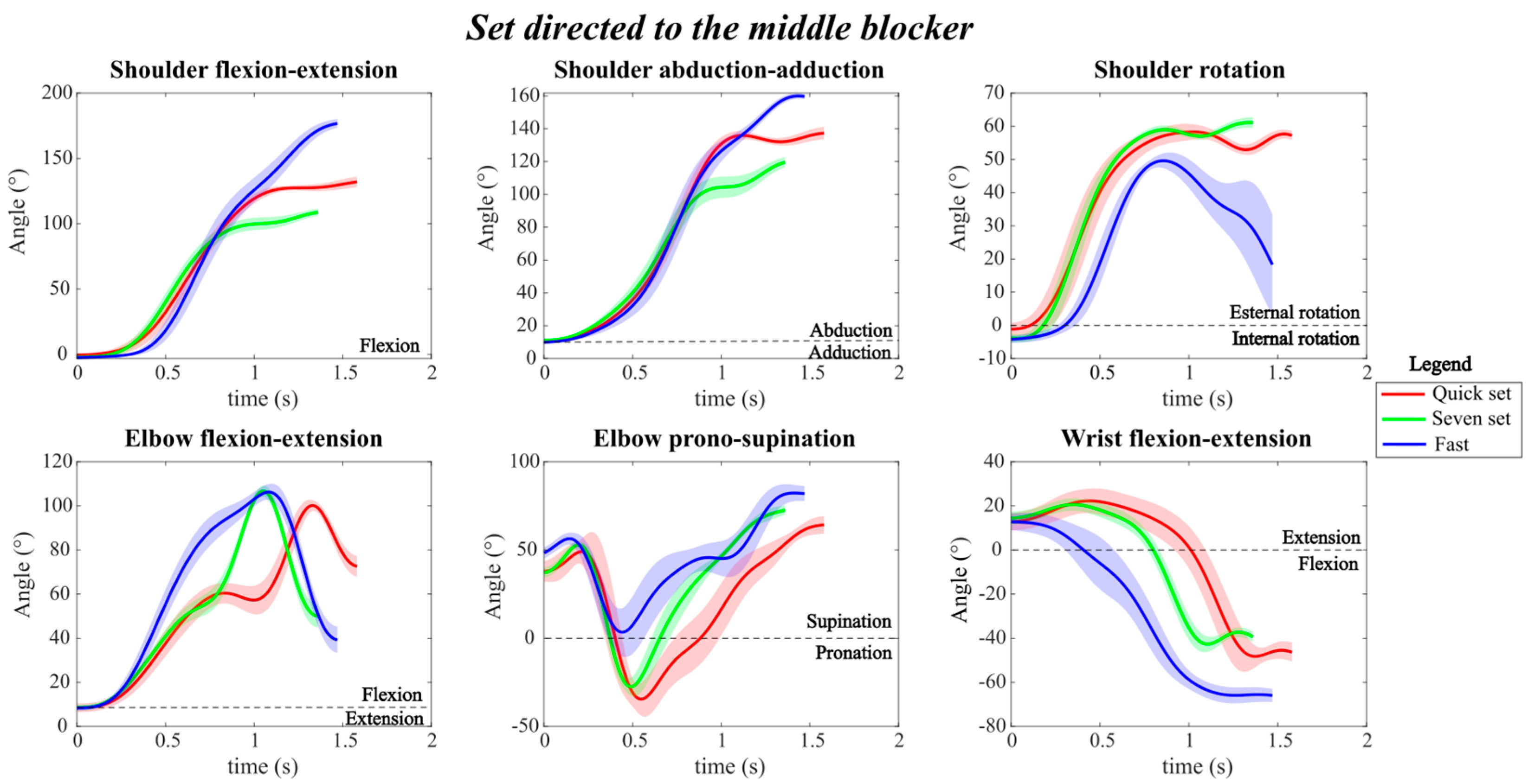

4.1. Joint Angles

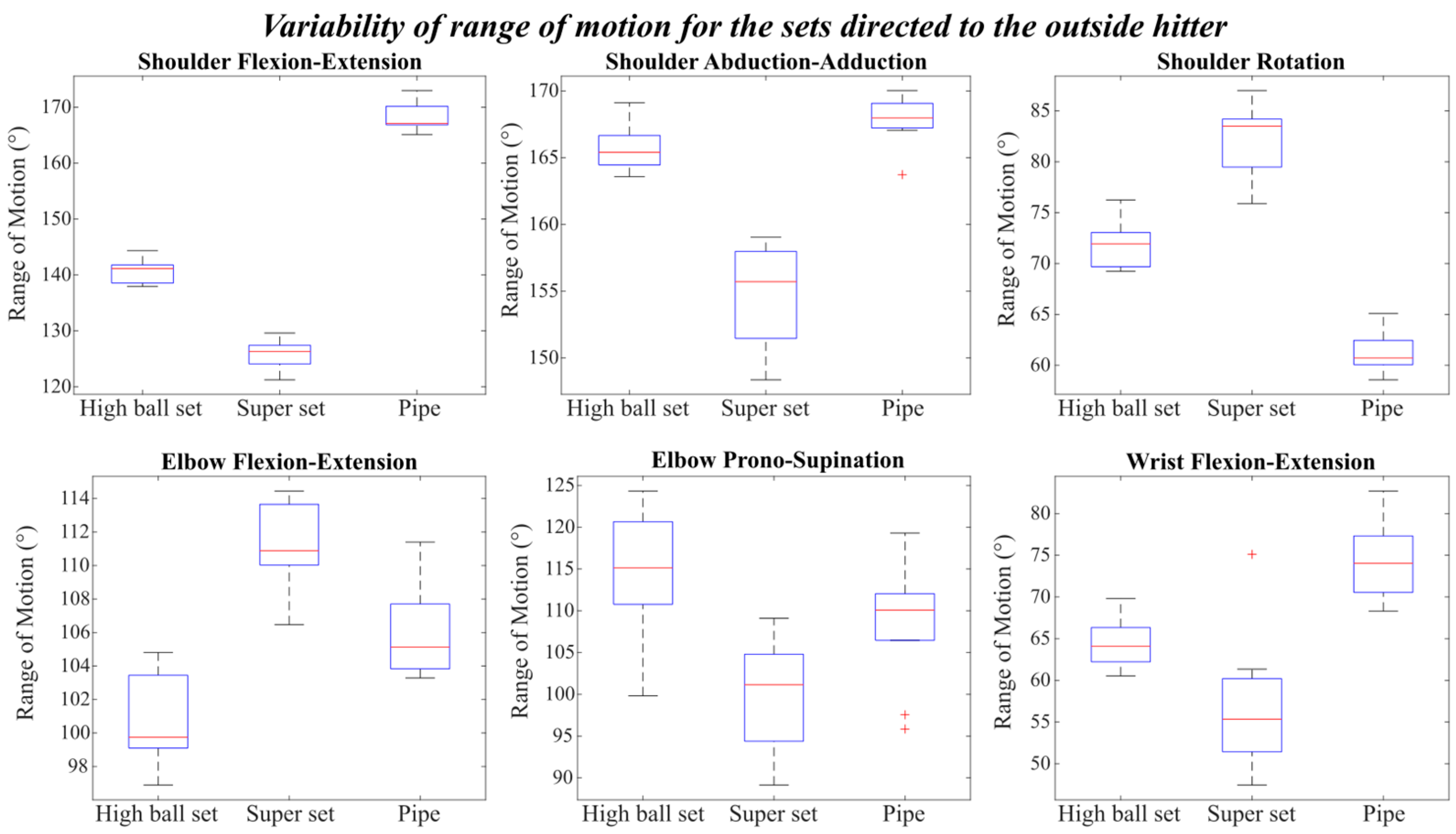

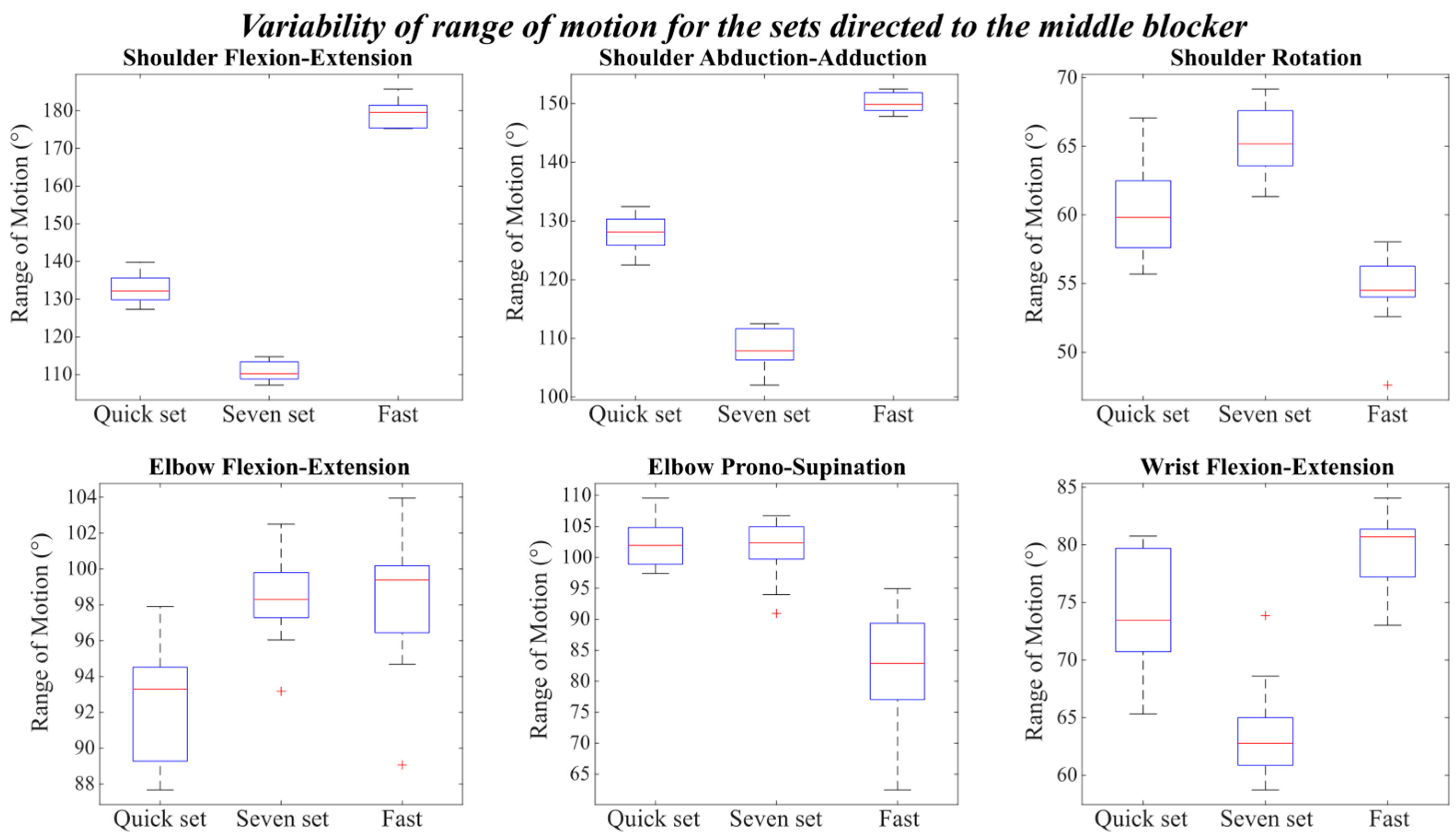

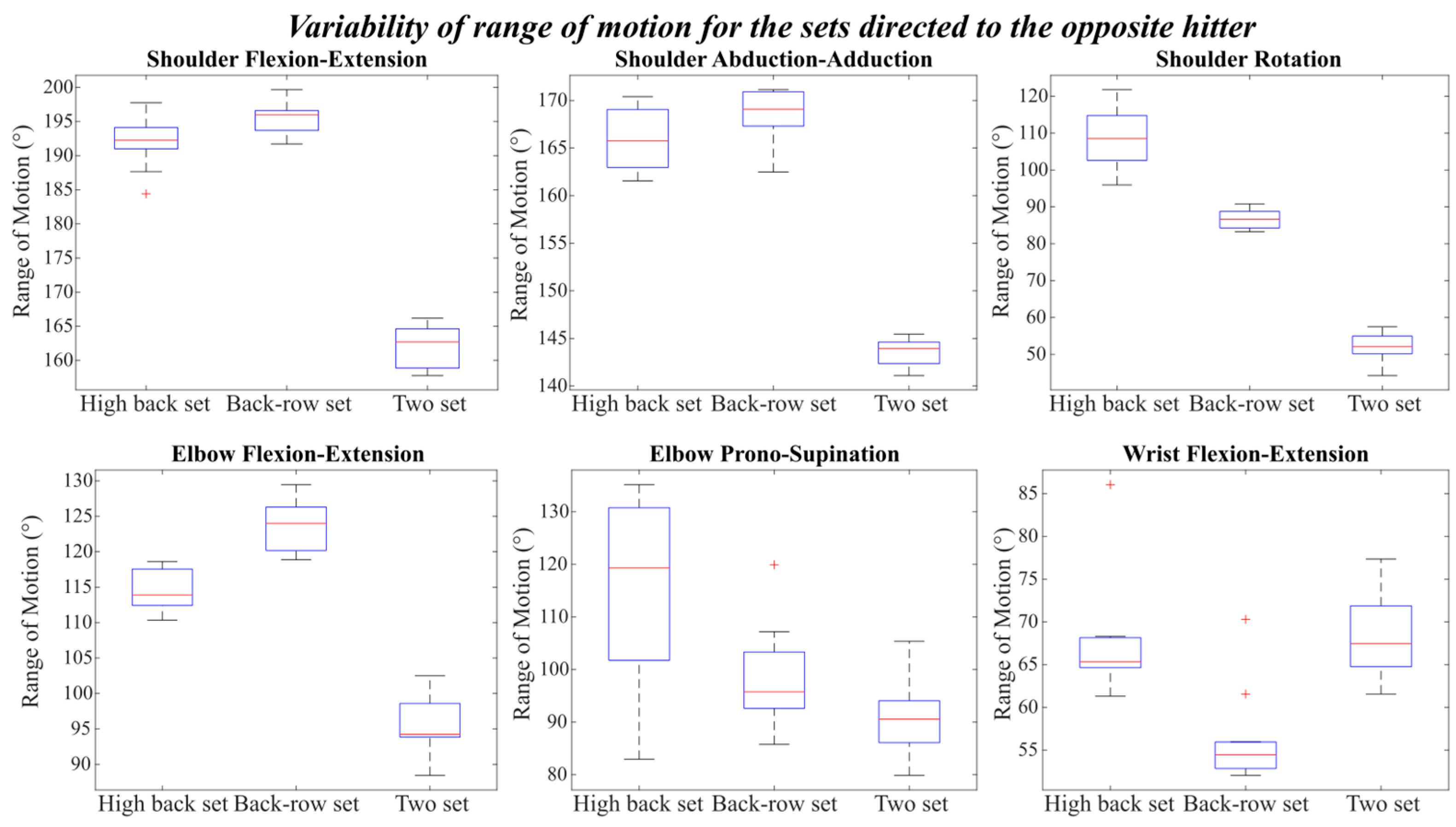

4.2. Range of Motion

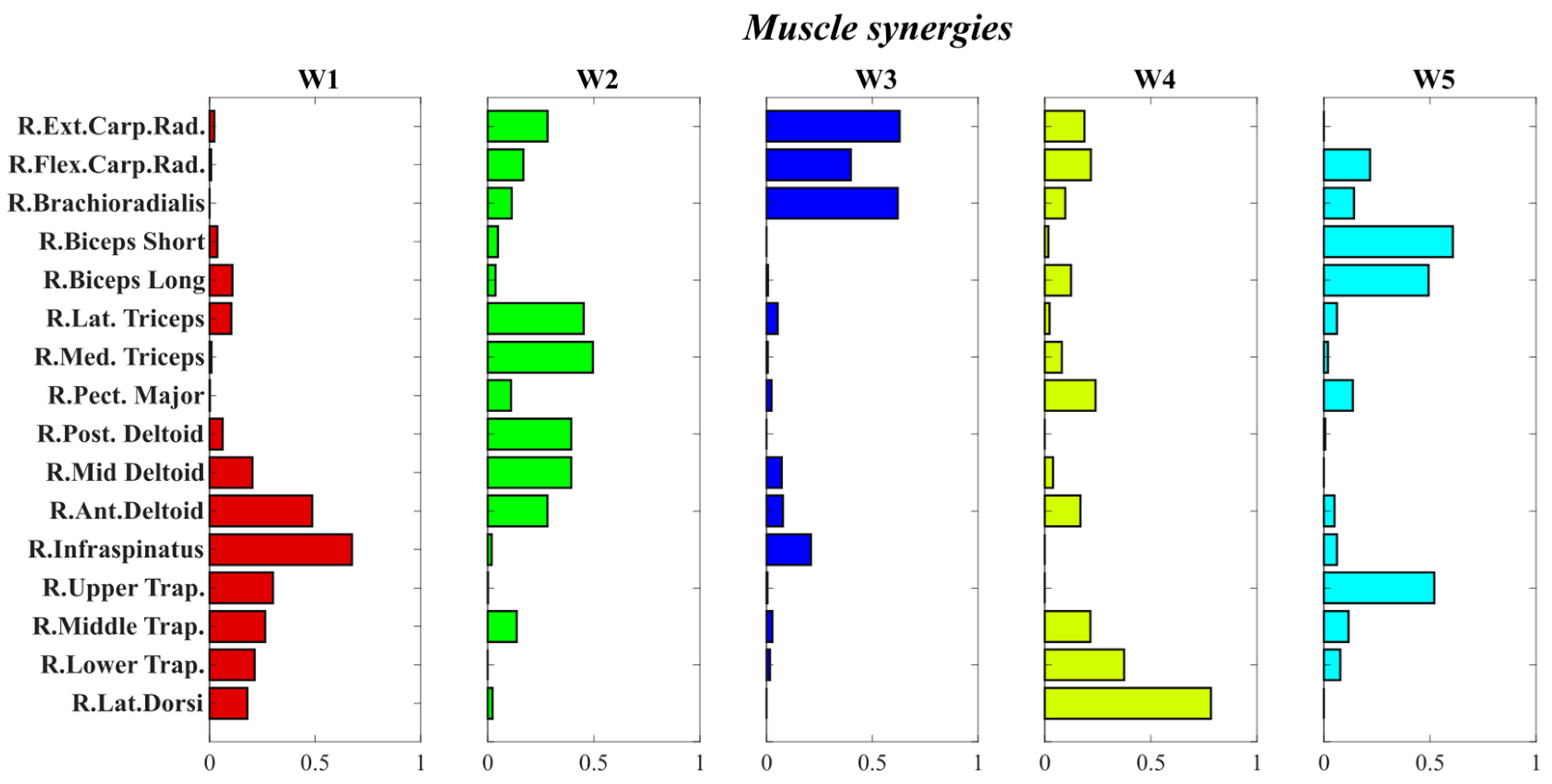

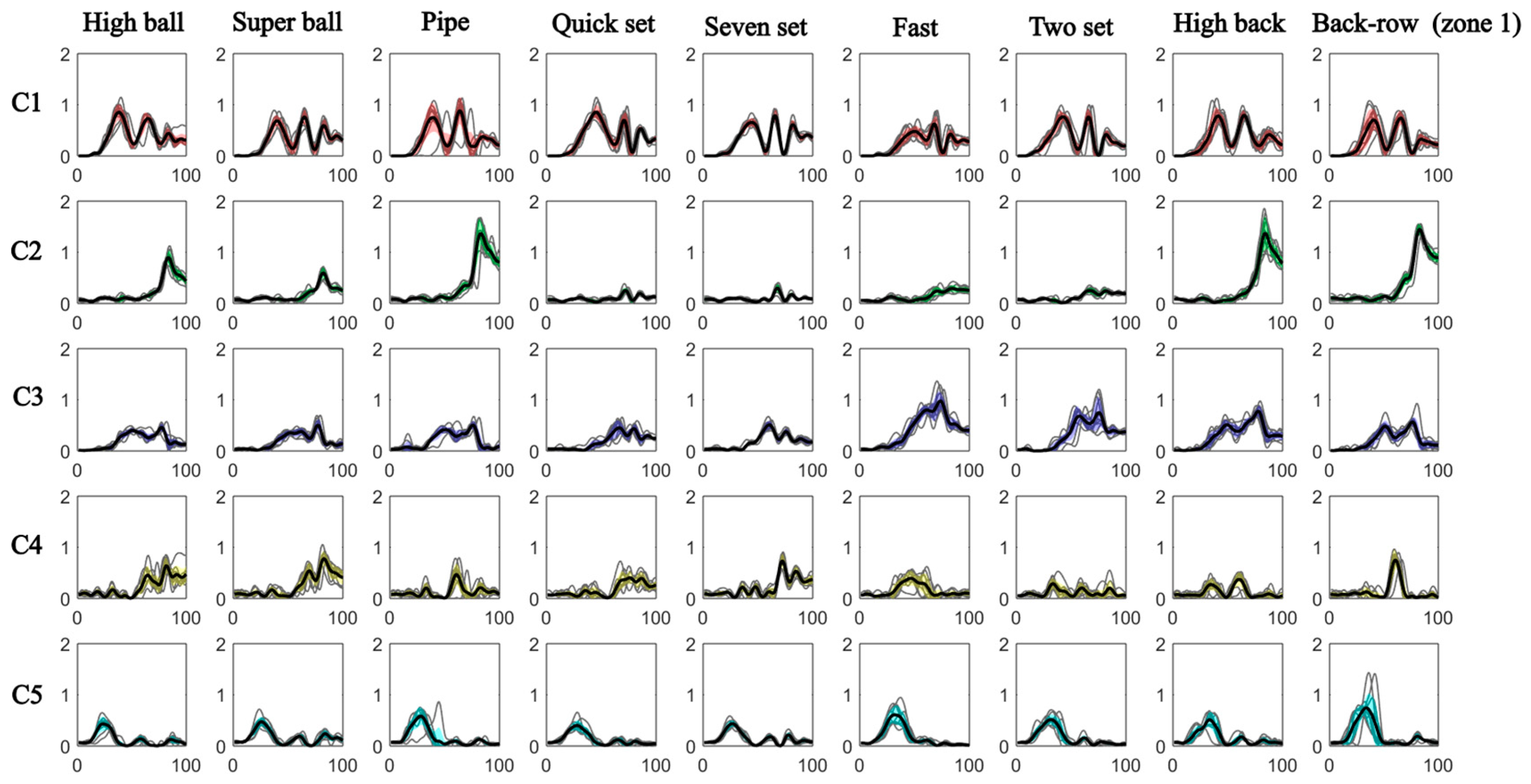

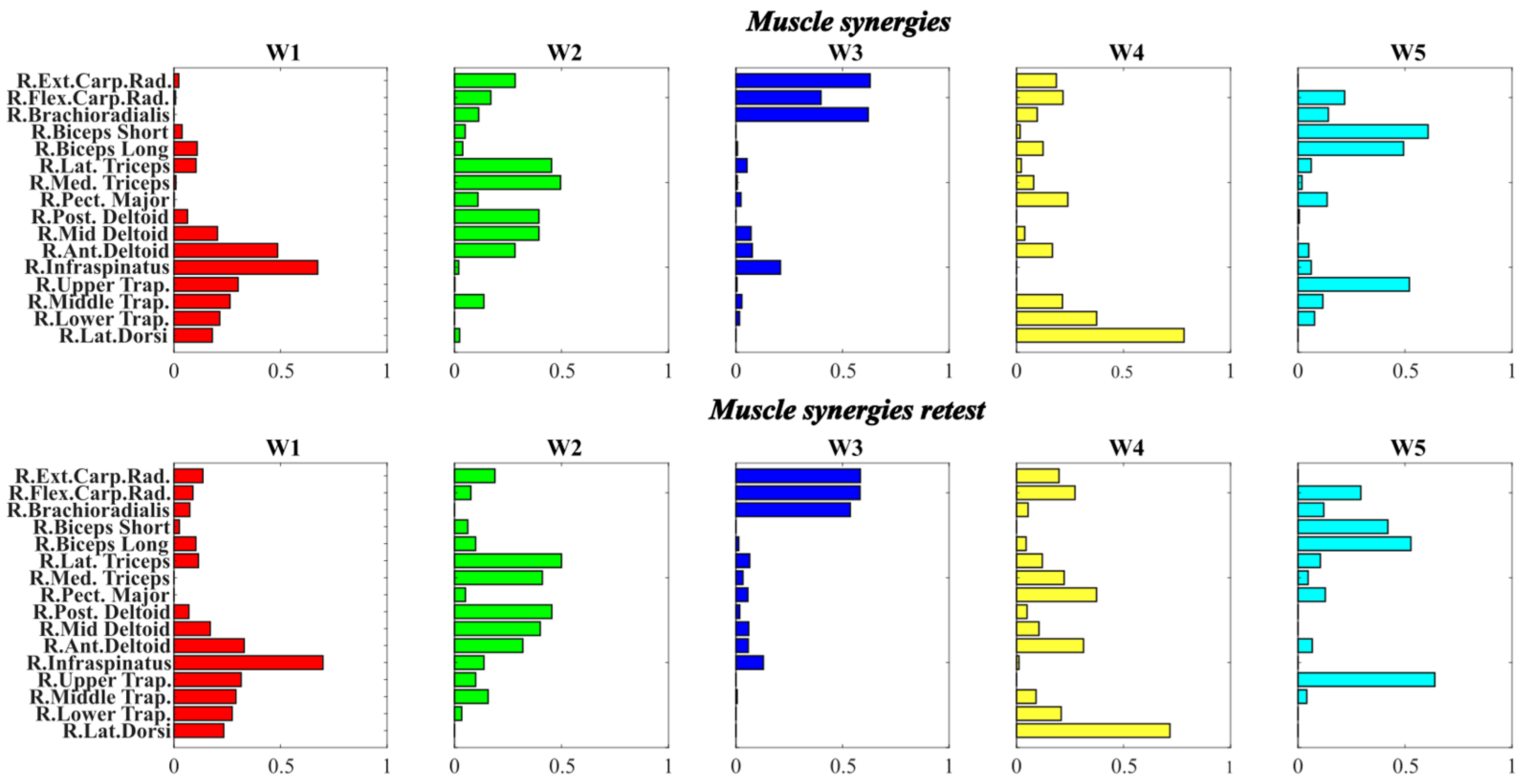

4.3. Muscle Synergies

4.4. Test–Retest

4.4.1. Muscle Synergies Similarity

4.4.2. Pearson’s Coefficient and Interclass Correlation Coefficient for the Kinematic Patterns of the Joint Angles

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Results and Added Value of the Protocol

5.2. Expected Outcomes and Application of the Protocol

5.3. Validity and Methodological Limitations

5.4. Test–Retest Reliability

5.5. Interpretation of Muscle Synergies

5.6. Practical Applications for Coaches and Clinicians

5.7. Suggestions for Protocol Improvement

6. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EMG | Electromyographic |

| NMF | Non-negative matrix factorization |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| r | Pearson’s coefficient |

References

- Fuchs, P.X.; Menzel, H.J.K.; Guidotti, F.; Bell, J.; von Duvillard, S.P.; Wagner, H. Spike jump biomechanics in male versus female elite volleyball players. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 2411–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabarkapa, D.V.; Cabarkapa, D.; Fry, A.C.; Whiting, S.M.; Downey, G.G. Kinetic and Kinematic Characteristics of Setting Motions in Female Volleyball Players. Biomechanics 2022, 2, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Silva, J.; Domínguez, A.M.; Fernández-Echeverría, C.; Rabaz, F.C.; Arroyo, M.P.M. Analysis of Setting Efficacy in Young Male and Female Volleyball Players. J. Hum. Kinet. 2016, 53, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denardi, R.A.; Romero Clavijo, F.A.; De Souza Santana, T.; Costa De Oliveira, T.A.; Corrêa, U.C. The interpersonal coordination constraint on the volleyball setter’s decision-making on setting direction. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2024, 19, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeser, J.C.; Fleisig, G.S.; Bolt, B.; Ruan, M. Upper Limb Biomechanics During the Volleyball Serve and Spike. Sports Health 2010, 2, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatahi, A.; Sadeghi, H.; Yousefian Molla, R.; Ameli, M. Selected Kinematic Characteristics Analysis of Knee and Ankle Joints During Block Jump Among Elite Junior Volleyball Players. Phys. Treat. Specif. Phys. Ther. J. 2019, 9, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.T.; Huang, Y.C.; Li, Y.Y.; Chang, J.H. The effect of rectus abdominis fatigue on lower limb jumping performance and landing load for volleyball players. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.; Tilp, M.; Von Duvillard, S.P.V.; Mueller, E. Kinematic analysis of volleyball spike jump. Int. J. Sports Med. 2009, 30, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokito, A.S.; Jobe, F.W.; Pink, M.M.; Perry, J.; Brault, J. Electromyographic analysis of shoulder function during the volleyball serve and spike. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. Board Trustees 1998, 7, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, E.Y.; Amorim, C.F.; de Camargo Neves Sacco, I. Influence of ankle functional instability on the ankle electromyography during landing after volleyball blocking. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2009, 19, e84–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Huang, C.-F. Kinematical analysis of female volleyball spike. In ISBS Conference Proceedings Archive; International Society of Biomechanics in Sports: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2008; pp. 617–620. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, S.; Benham, A.S.; Northcott, S.R. A three-dimensional cinematographical analysis of the volleyball spike. J. Sports Sci. 1993, 11, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, L.d.S.; Moura, T.B.M.A.; Rodacki, A.L.F.; Tilp, M.; Okazaki, V.H.A. A systematic review of volleyball spike kinematics: Implications for practice and research. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2020, 15, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Hu, L.-H. Kinematic analysis of volleyball jump topspin and float serve. In Proceedings of the XXV ISBS Symposium, International Society of Biomechanics in Sports, Ouro Preto, Brazil, 23–27 August 2007; pp. 333–336. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.C.; Hu, U.H.; Huang, C.; Sheu, T.Y.; Tsue, C.M. Kinetic and Kinematic differences of two volleyball-spiking jump. In ISBS Conference Proceedings Archive; International Society of Biomechanics in Sports: Extremadura, Spain, 2002; pp. 148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, S.; Delattre, N.; Berton, E.; Divrechy, G.; Rao, G. Comparison of landing kinematics and kinetics between experienced and novice volleyball players during block and spike jumps. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozawa, Y.; Uchiyama, S.; Ogawara, K.; Kanosue, K.; Yamada, H. Biomechanical analysis of volleyball overhead pass. Sports Biomech. 2021, 20, 844–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgway, M.E.; Wilkerson, J. A kinematic analysis of the front set and back set in volleyball. In ISBS Conference Proceedings Archive; International Society of Biomechanics in Sports: Halifax, NS, Canada, 1986; pp. 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Adlou, B.; Wilburn, C.; Weimar, W. Motion Capture Technologies for Athletic Performance Enhancement and Injury Risk Assessment: A Review for Multi-Sport Organizations. Sensors 2025, 25, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborri, J.; Keogh, J.; Kos, A.; Santuz, A.; Umek, A.; Urbanczyk, C.; van der Kruk, E.; Rossi, S. Sport biomechanics applications using inertial, force, and EMG sensors: A literature overview. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2020, 2020, 2041549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.; Ullah, A. Advanced biomechanical analytics: Wearable technologies for precision health monitoring in sports performance. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, H.J.; Freriks, B.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2000, 10, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scano, A.; Dardari, L.; Molteni, F.; Giberti, H.; Tosatti, L.M.; D’Avella, A. A comprehensive spatial mapping of muscle synergies in highly variable upper-limb movements of healthy subjects. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghislieri, M.; Lanotte, M.; Knaflitz, M.; Rizzi, L.; Agostini, V. Muscle synergies in Parkinson’s disease before and after the deep brain stimulation of the bilateral subthalamic nucleus. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pale, U.; Atzori, M.; Müller, H.; Scano, A. Variability of muscle synergies in hand grasps: Analysis of intra- and inter-session data. Sensors 2020, 20, 4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimini, D.; Agostini, V.; Knaflitz, M. Intra-subject consistency during locomotion: Similarity in shared and subject-specific muscle synergies. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brambilla, C.; Russo, M.; d’Avella, A.; Scano, A. Phasic and tonic muscle synergies are different in number, structure and sparseness. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2023, 92, 103148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.D.; Sebastian Seung, H. Learning the parts of objects by non negative matrix factorization. Nature 1999, 401, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Avella, A.; Portone, A.; Fernandez, L.; Lacquaniti, F. Control of fast-reaching movements by muscle synergy combinations. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 7791–7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, J.P. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Lanzani, V.; Brambilla, C.; Scano, A. Kinematic–Muscular Synergies Describe Human Locomotion with a Set of Functional Synergies. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qiu, F.; Gan, L.; Chou, L.S. Concurrent validity of inertial measurement units in range of motion measurements of upper extremity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Wearable Technol. 2024, 5, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, R.E.; Lambiase, J.; Riffitts, M.; Scholle, L.; Kulkarni, S.; Luck, C.L.; Parmanto, D.; Putraadinatha, V.; Yoga, M.D.; Lang, S.N.; et al. The Reliability and Validity of an Instrumented Device for Tracking the Shoulder Range of Motion. Sensors 2025, 25, 3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryhoda, M.; Newell, K.M.; Wilson, C.; Irwin, G. Task Specific and General Patterns of Joint Motion Variability in Upright-and Hand-Standing Postures. Entropy 2022, 24, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D.G.E. Research Methods in Biomechanics; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fleisig, G.S.; Escamilla, R.F.; Andrews, J.R. Applied Biomechanics of Baseball Pitching; Elsevier Saunders: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Li, F.; Cao, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X. Muscle Synergy Analysis for Similar Upper Limb Motor Tasks. In Proceedings of the 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Chicago, IL, USA, 26–30 August 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Scano, A.; Lanzani, V.; Brambilla, C. How Recent Findings in Electromyographic Analysis and Synergistic Control Can Impact on New Directions for Muscle Synergy Assessment in Sports. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavynia, S.; Torres-Oviedo, G.; Ting, L. Muscle synergies: Implications for clinical evaluation and rehabilitation of movement. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2011, 17, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, Y.; Matsunaga, N.; Akuzawa, H.; Kojima, T.; Oshikawa, T.; Iizuka, S.; Okuno, K.; Kaneoka, K. Difference in muscle synergies of the butterfly technique with and without swimmer’s shoulder. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.J.; Castillo, G.C.; Topley, M.; Paul, R.W. The Effects of Fatigue on Muscle Synergies in the Shoulders of Baseball Players. Sports Health 2023, 15, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| W1 | W2 | W3 | W4 | W5 | |

| Similarity | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.96 |

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | |

| High ball | 0.95 (<0.001) | 0.98 (<0.001) | 0.84 (<0.001) | 0.95 (<0.001) | 0.95 (<0.001) |

| Super ball | 0.86 (<0.001) | 0.91 (<0.001) | 0.91 (<0.001) | 0.98 (<0.001) | 0.98 (<0.001) |

| Pipe | 0.93 (<0.001) | 0.99 (<0.001) | 0.73 (<0.001) | 0.74 (<0.001) | 0.93 (<0.001) |

| Quick set | 0.91 (<0.001) | 0.74 (<0.001) | 0.94 (<0.001) | 0.75 (<0.001) | 0.93 (<0.001) |

| Seven set | 0.94 (<0.001) | 0.36 (<0.001) | 0.96 (<0.001) | 0.90 (<0.001) | 0.97 (<0.001) |

| Fast | 0.84 (<0.001) | 0.93 (<0.001) | 0.90 (<0.001) | 0.47 (<0.001) | 0.92 (<0.001) |

| Two | 0.98 (<0.001) | 0.94 (<0.001) | 0.98 (<0.001) | 0.62 (<0.001) | 0.98 (<0.001) |

| High back | 0.88 (<0.001) | 0.99 (<0.001) | 0.93 (<0.001) | 0.79 (<0.001) | 0.98 (<0.001) |

| Back-row (zone 1) | 0.89 (<0.001) | 0.99 (<0.001) | 0.86 (<0.001) | 0.89 (<0.001) | 0.98 (<0.001) |

| Joints Movement | Correlation and Reliability Coefficients (r, ICC) | Sets Directed to the Outside Hitter | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Ball | Super Ball | Pipe | ||

| Shoulder Flexion-Extension | r | 0.9969 (<0.001) | 0.9999 (<0.001) | 0.9979 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9963 [0.9950; 0.9972] | 0.9903 [0.9896; 0.9928] | 0.9976 [0.9969; 0.9981] | |

| Shoulder Abduction-Adduction | r | 0.9969 (<0.001) | 0.9993 (<0.001) | 0.9973 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9929 [0.9904; 0.9947] | 0.9891 [0.9853; 0.9919] | 0.9940 [0.9923; 0.9953] | |

| Shoulder Rotation | r | 0.9941 (<0.001) | 0.9995 (<0.001) | 0.9955 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9674 [0.9561; 0.9758] | 0.9367 [0.9154; 0.9527] | 0.9357 [0.9180; 0.9496] | |

| Elbow Flexion-Extension | r | 0.9895 (<0.001) | 0.9908 (<0.001) | 0.9965 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9870 [0.9824; 0.9903] | 0.9824 [0.9763; 0.9870] | 0.9939 [0.9922; 0.9953] | |

| Elbow Prono-Supination | r | 0.9578 (<0.001) | 0.9445 (<0.001) | 0.9812 (0.0646) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9309 [0.9077; 0.9484] | 0.8378 [0.7870; 0.8773] | 0.9556 [0.9432; 0.9653] | |

| Wrist Flexion-Extension | r | 0.9975 (<0.001) | 0.9908 (<0.001) | 0.9937 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9941 [0.9920; 0.9956] | 0.9865 [0.9818; 0.9900] | 0.9414 [0.9252; 0.9541] | |

| Joints Movement | Correlation and Reliability Coefficients (r, ICC) | Sets Directed to the Middle Blocker | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quick Set | Seven Set | Fast | ||

| Shoulder Flexion-Extension | r | 0.9952 (<0.001) | 0.9995 (<0.001) | 0.9984 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9942 [0.9921; 0.9958] | 0.9984 [0.9977; 0.9988] | 0.9974 [0.9965; 0.9981] | |

| Shoulder Abduction-Adduction | r | 0.9955 (<0.001) | 0.9991 (<0.001) | 0.9992 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9858 [0.9804; 0.9897] | 0.9913 [0.9879; 0.9937] | 0.9945 [0.9926; 0.9959] | |

| Shoulder Rotation | r | 0.9958 (<0.001) | 0.9996 (<0.001) | 0.8686 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9843 [0.9783; 0.9886] | 0.9778 [0.9694; 0.9840] | 0.8525 [0.8066; 0.8882] | |

| Elbow Flexion-Extension | r | 0.9806 (<0.001) | 0.9938 (<0.001) | 0.9649 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9786 [0.9706; 0.9845] | 0.9843 [0.9783; 0.9886] | 0.9130 [0.8848; 0.9346] | |

| Elbow Prono-Supination | r | 0.9706 (<0.001) | 0.9502 (<0.001) | 0.8582 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9354 [0.9119; 0.9528] | 0.9162 [0.8857; 0.9389] | 0.8412 [0.7921; 0.8795] | |

| Wrist Flexion-Extension | r | 0.9801 (<0.001) | 0.9917 (<0.001) | 0.9735 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9298 [0.9044; 0.9487] | 0.9515 [0.9333; 0.9648] | 0.9486 [0.9315; 0.9615] | |

| Joints Movement | Correlation and Reliability Coefficients (r, ICC) | Sets Directed to the Opposite Hitter | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Back | Back-Row (Zone 1) | Two | ||

| Shoulder Flexion-Extension | r | 0.9990 (<0.001) | 0.9976 (<0.001) | 0.9995 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9754 [0.9671; 0.9816] | 0.9962 [0.9948; 0.9972] | 0.9989 [0.9984; 0.9992] | |

| Shoulder Abduction-Adduction | r | 0.9913 (<0.001) | 0.9841 (<0.001) | 0.9961 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9804 [0.9738; 0.9854] | 0.9573 [0.9429; 0.9682] | 0.9855 [0.9800; 0.9895] | |

| Shoulder Rotation | r | 0.6724 (<0.001) | 0.9188 (<0.001) | 0.9522 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.5713 [0.4642; 0.6620] | 0.5051 [0.3857; 0.6079] | 0.6973 [0.6038; 0.7718] | |

| Elbow Flexion-Extension | r | 0.9959 (<0.001) | 0.9901 (<0.001) | 0.9902 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9956 [0.9941; 0.9967] | 0.9469 [0.9291; 0.9604] | 0.9707 [0.9597; 0.9788] | |

| Elbow Prono-Supination | r | 0.8183 (<0.001) | 0.7975 (<0.001) | 0.8046 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.6099 [0.5094; 0.6940] | 0.7653 [0.6959; 0.8205] | 0.6991 [0.6061; 0.7732] | |

| Wrist Flexion-Extension | r | 0.9827 (<0.001) | 0.9481 (<0.001) | 0.9653 (<0.001) |

| ICC (95% CI) | 0.9426 [0.9237; 0.9569] | 0.9137 [0.8853; 0.9353] | 0.9492 [0.9304; 0.9631] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lanzani, V.; Brambilla, C.; Moscatelli, N.; Scano, A. A Protocol for the Biomechanical Evaluation of the Types of Setting Motions in Volleyball Based on Kinematics and Muscle Synergies. Methods Protoc. 2026, 9, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010006

Lanzani V, Brambilla C, Moscatelli N, Scano A. A Protocol for the Biomechanical Evaluation of the Types of Setting Motions in Volleyball Based on Kinematics and Muscle Synergies. Methods and Protocols. 2026; 9(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleLanzani, Valentina, Cristina Brambilla, Nicol Moscatelli, and Alessandro Scano. 2026. "A Protocol for the Biomechanical Evaluation of the Types of Setting Motions in Volleyball Based on Kinematics and Muscle Synergies" Methods and Protocols 9, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010006

APA StyleLanzani, V., Brambilla, C., Moscatelli, N., & Scano, A. (2026). A Protocol for the Biomechanical Evaluation of the Types of Setting Motions in Volleyball Based on Kinematics and Muscle Synergies. Methods and Protocols, 9(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010006