Human Amniotic Membrane Procurement Protocol and Evaluation of a Simplified Alkaline Decellularization Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Design

- −

- 30 cm container;

- −

- Plastic kidney dish;

- −

- Curved Mayo scissors;

- −

- Surgical gown;

- −

- Surgical drape;

- −

- Empty storage container;

- −

- Gauze pads;

- −

- Surgical towel;

- −

- Pairs of surgical gloves (a pair half a size larger than the other).

- −

- Gauze pads

- −

- Toothless dissection forceps

- −

- Mayo tray

- −

- Plastic mesh

- −

- Self-sealing pouch (13.5 cm × 25.5 cm).

- −

- 200 mL of sterile water;

- −

- 1 L Saline solution (0.9%) with antibiotic–antimycotic cocktail (including 100 μg/mL gentamicin);

- −

- 2 L PBS containing antibiotic–antimycotic cocktail (including 100 μg/mL gentamicin).

- −

- 500 mL 0.1 M NaOH;

- −

- 500 mL 0.5 M NaOH;

- −

- 500 mL 0.1%Tween 80;

- −

- 500 mL 0.15% peracetic acid in ethanol (96% v/v);

- −

- 500 mL PBS.

3. Procedure

3.1. Donor Selection and Informed Consent

3.2. Placenta Procurement

- Collect the placenta (n = 12) immediately after cesarean delivery under aseptic conditions.

- Place the placenta into a sterile bowl together with a disposable umbilical clamp.

- Position the placenta with the fetal surface (continuous with the umbilical cord) facing upward.

- Clamp the umbilical cord 1–2 cm above the placental surface using the disposable clamp.

- Compress the umbilical cord with sterile gauze to drain remaining blood and cut above the clamp using Mayo scissors.

3.2.1. Rinsing and Surface Cleaning

- Rinse the placenta multiple times with sterile saline or an antibiotic–antimycotic solution (penicillin, streptomycin, neomycin, and amphotericin B) to eliminate bacteria and fungi [21].

- Clean the fetal surface gently with sterile gauze to remove blood and residual tissue debris.

- Place the placenta fetal side up in a sterile container lined with a laparotomy sponge to absorb maternal blood and maintain a clean working area.

3.2.2. Amniotic Membrane Separation

- Identify the amniotic membrane as the translucent layer continuous with the umbilical cord epithelium.

- Locate a natural separation plane between the amniotic membrane (AM) and chorion if present.

- Separate the AM from the chorion by gently lifting and dissecting the membrane.Note: Process placentas with central cord insertion by separating the membrane centripetally, moving from the periphery toward the cord.Process placentas with eccentric cord insertion by first cutting around the cord and then lifting and separating the membrane laterally.

- 5.

- Perform careful dissection in areas with generalized rupture to avoid tissue damage (Figure 1).

- 6.

- Cut the AM around the umbilical cord using Mayo scissors to free the membrane from its attachment.Note: The membranes appeared uniformly thin, elastic, and transparent, with minimal residual blood following thorough rinsing with sterile saline (Figure 2).

- 7.

- Roll the amniotic membrane (AM) carefully with the epithelial surface facing outward around sterile gauze.

- 8.

- Place the rolled membrane into a sterile 50 mL tube in sterile saline or PBS (Figure 3).

3.2.3. Rising and Surface Cleaning

- Introduce the container with the AM and an isotonic rinsing solution to a laminar flow hood.

- Transfer the membrane with sterile forceps onto a sterile mesh-lined tray and rinse thoroughly on both sides using the rinsing solution [24].

- Inspect the AM macroscopically to exclude any visible anomalies and confirm tissue integrity.

- Roll the AM around gauze with the epithelial surface facing outward and store in a 50 mL sterile tube.

- Label the tube with the procurement date, the donor’s full name, and their medical record number.

- Use fresh AM soaked in antimicrobial solution only for short-term applications, noting its limited sterility and short shelf life.

- Freeze the AM at −28 °C (up to 8 months) or −80 °C for long-term preservation (up to 2 years), ensuring access to appropriate freezing equipment and pretreatment steps prior to use [25].

- Assign the membranes to two different decellularization protocols (n = 5 total) according to the comparative study design.

3.2.4. Decellularization

Alkaline Decellularization Protocol (Modified from Saghizadeh et al. [18])

- Thaw the frozen amniotic membranes stored at −80 °C by immersing them in PBS for 10–30 min at room temperature.

- Place each membrane with the epithelial surface facing upward.

- Soak a cotton-tipped applicator in 0.5 M NaOH.

- Gently rub the epithelial surface with the NaOH-soaked applicator to initiate epithelial removal.

- Immerse the membrane in 0.5 M NaOH for 20–30 s.

- Transfer the membrane immediately to PBS to stop the alkaline reaction.

- Wash the membrane in PBS two to three times, each wash lasting 10 to 15 min.

- Maintain gentle agitation during all washes to ensure uniform treatment and prevent structural damage.

Detergent Alkaline Decellularization Protocol (Modified from Villamil-Ballesteros et al. [26])

- Thaw the frozen amniotic membranes at room temperature for 2 h.

- Immerse each membrane in 0.1% Tween 80 for 4 h with continuous mechanical stirring.

- Transfer the membrane to 0.1 M NaOH and incubate for 1 h.

- Prepare an acid solution consisting of 0.15% peracetic acid in ethanol (96% v/v).

- Soak the membrane in the peracetic acid/ethanol solution for 12 h under mechanical stirring.

- Wash the membrane in 70% ethanol for 1 h.

- Buffer the membrane in PBS for 2 h with agitation.

- Immerse the membrane again in 0.1 M NaOH for 1 h.

- Transfer the membrane back into 0.15% peracetic acid for 1 h.

- Wash the membrane in PBS four times to remove residual chemicals.

- Remove residual ethanol completely by performing three additional PBS washes, 2 h each.

- Store the processed membrane at −80 °C.Note: Maintain gentle agitation throughout all steps to ensure homogeneous chemical exposure and to minimize ultrastructural damage. Can apply optional antimicrobial or irradiation steps as needed to enhance disinfection, consistent with detergent-based decellularization practices

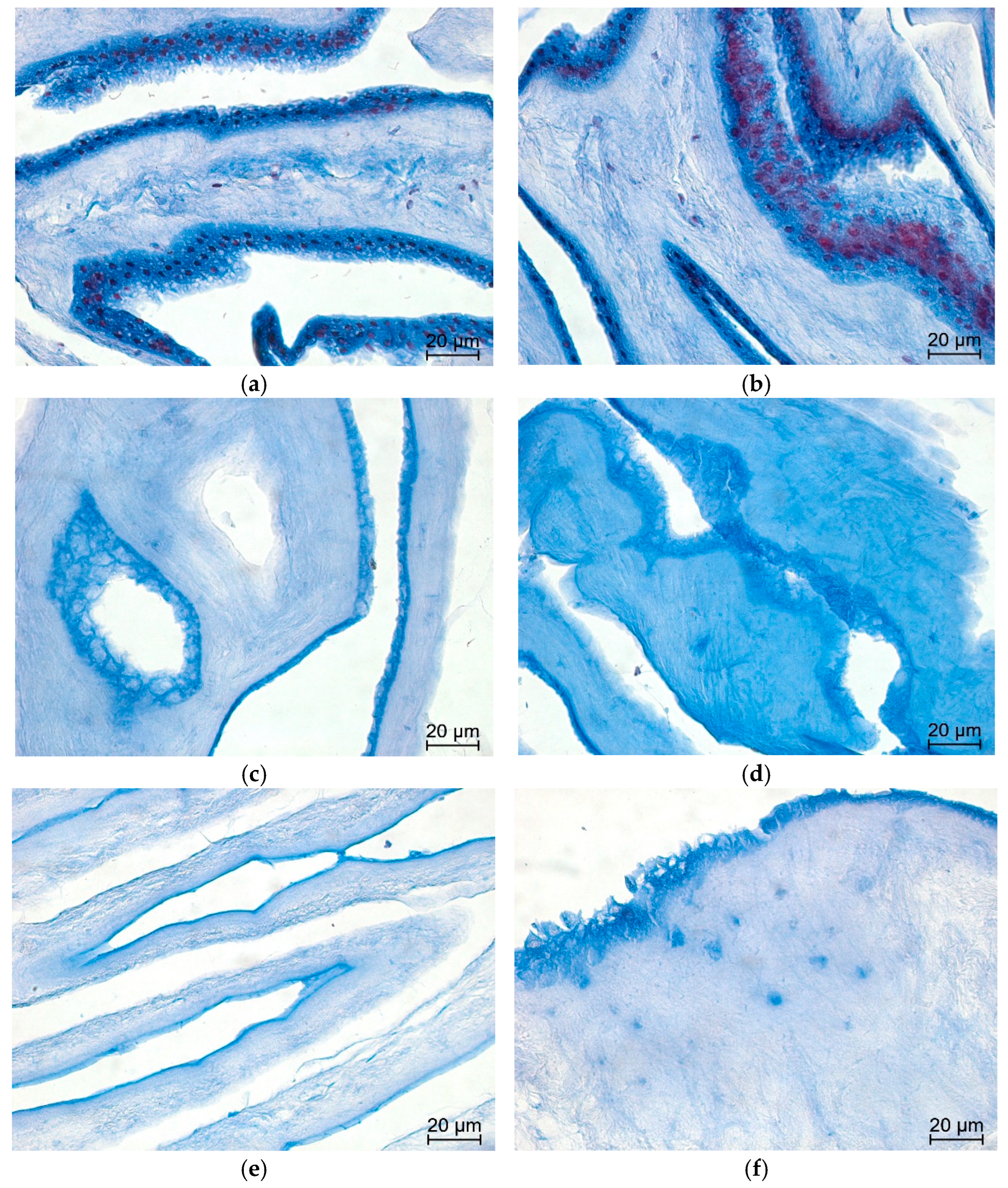

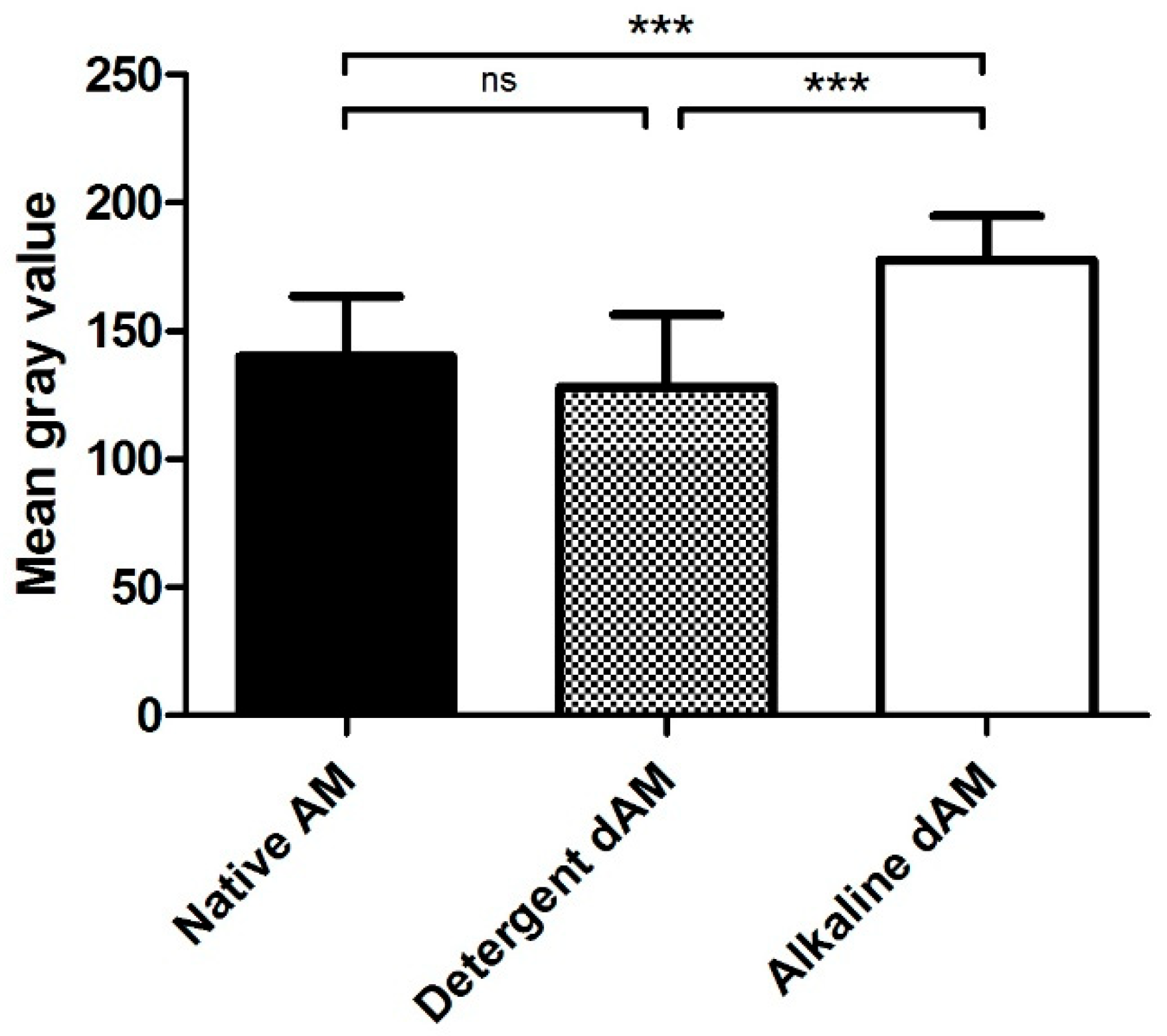

3.3. Histology

- Fix tissue samples (native AM and decellularized AMs) in 4% neutral-buffered formalin for 24 h at room temperature.

- Dehydrate samples through a graded ethanol series.

- Clear samples in xylene.

- Embed samples in paraffin.

- Cut paraffin sections at 4 µm thickness using a microtome and mount sections on glass slides.Note: For each sample in all groups (two biological replicates, each stained in duplicate), three tissue sections were analyzed per slide, and eight non-overlapping high-power fields (HPFs) were randomly selected for evaluation.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AM | Amniotic membrane |

| dAM | Decellularized amniotic membrane |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| HBSS | Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution |

| HPF | High-power field |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

References

- Baergen, R.N. Manual of Pathology of the Human Placenta, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fénelon, M.; Catros, S.; Meyer, C.; Fricain, J.C.; Obert, L.; Auber, F.; Louvrier, A.; Gindraux, F. Applications of human amniotic membrane for tissue engineering. Membranes 2021, 11, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, F.W.B.; Huang, J.; Alió del Barrio, J.L.; Hamada, S.; McAlinden, C. Amniotic membrane transplantation: Structural and biological properties, tissue preparation, application and clinical indications. Eye 2024, 38, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Ni, R.; Hu, Y.; Yang, F.; Du, T.; Zhu, Y. Biological importance of human amniotic membrane in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Mater. Today Bio. 2023, 22, 100790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, C.; Jain, A.K. Human amniotic membrane transplantation: Different modalities of its use in ophthalmology. World J. Transplant. 2014, 4, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Torres, J.R.; Martínez-González, S.B.; Lozano-Luján, A.D.; Martínez-Vázquez, M.C.; Velasco-Elizondo, P.; Garza-Veloz, I.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L. Biological properties and surgical applications of the human amniotic membrane. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 10, 1067480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkhenany, H.; El-Derby, A.; Abd Elkodous, M.; Salah, R.A.; Lotfy, A.; El-Badri, N. Applications of the amniotic membrane in tissue engineering and regeneration: The hundred-year challenge. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, M.; Stachon, T.; Seitz, B.; Huber, M.; Zawada, M.; Langenbucher, A.; Szentmáry, N. Growth Factor and Interleukin Concentrations in Amniotic Membrane-Conditioned Medium. Curr. Eye Res. 2017, 42, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koizumi, N.; Inatomi, T.; Sotozono, C.; Fullwood, N.J.; Quantock, A.J.; Kinoshita, S. Growth factor mRNA and protein in preserved human amniotic membrane. Curr. Eye Res. 2000, 20, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywocz, Z.; Pius-Sadowska, E.; Klos, P.; Gryzik, M.; Wasilewska, D.; Aleksandrowicz, B.; Dworczynska, M.; Sabalinska, S.; Hoser, G.; Machalinski, B.; et al. Growth factors and their receptors derived from human amniotic cells in vitro. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2014, 52, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litwiniuk, M.; Radowicka, M.; Krejner, A.; Śladowska, A.; Grzela, T. Amount and distribution of selected biologically active factors in amniotic membrane depends on the part of amnion and mode of childbirth. Can we predict properties of amnion dressing? A proof-of-concept study. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2018, 43, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbank, S.; Hildner, F.; Redl, H.; Van Griensven, M.; Gabriel, C.; Hennerbichler, S. Impact of human amniotic membrane preparation on release of angiogenic factors. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2009, 3, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah Tehrani, F.; Firouzeh, A.; Shabani, I.; Shabani, A. A Review on Modifications of Amniotic Membrane for Biomedical Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 606982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Marin, S.; Kern, T.; Hofmann, N.; Pogozhykh, O.; Framme, C.; Börgel, M.; Figueiredo, C.; Glasmacher, B.; Gryshkov, O. Human Amniotic Membrane: A review on tissue engineering, application, and storage. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2021, 109, 1198–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenelon, M.; BMaurel, D.; Siadous, R.; Gremare, A.; Delmond, S.; Durand, M.; Brun, S.; Catros, S.; Gindraux, F.; L’HEureux, N.; et al. Comparison of the impact of preservation methods on amniotic membrane properties for tissue engineering applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 104, 109903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, P.B.; Amini, N.; Joghataei, M.T.; Ebrahimi, L.; Amoupour, M.; Sarveazad, A.; Kargozar, S.; Mozafari, M. Decellularized human amniotic membrane: From animal models to clinical trials. Methods 2020, 171, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravimelal, S.; Momeni, M.; Gholipur, M.; Kundu, S.C.; Gholipourmalekabadi, M. Protocols for decellularization of human amniotic membrane. Methods Cell Biol. 2020, 157, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghizadeh, M.; Winkler, M.A.; Kramerov, A.A.; Hemmati, D.M.; Ghiam, C.A.; Dimitrijevich, S.D.; Sareen, D.; Ornelas, L.; Ghiasi, H.; Brunken, W.J.; et al. A simple alkaline method for decellularizing human amniotic membrane for cell culture. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholipourmalekabadi, M.; Mozafari, M.; Salehi, M.; Seifalian, A.; Bandehpour, M.; Ghanbarian, H.; Urbanska, A.M.; Sameni, M.; Samadikuchaksaraei, A.; Seifalian, A.M. Development of a cost-effective and simple protocol for decellularization and preservation of human amniotic membrane as a soft tissue replacement and delivery system for bone marrow stromal cells. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2015, 4, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavagnoli, D.C.F.; Assis, K.; Saraiva, P.G.C.; Saraiva, F.P.; Mello, L.G.M. Protocolo de captação, processamento e armazenamento de membrana amniótica humana para uso oftalmológico. e-Oftalmo 2023, 9, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirsova, K.; Jones, G.L.A. Amniotic membrane in ophthalmology: Properties, preparation, storage and indications for grafting—A review. Cell Tissue Bank. 2017, 18, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baergen, R.N. Pathology of the Umbilical Cord. Manual of Pathology of the Human Placenta; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 247–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, K.; Markel, L.; Odibo, A.; Duncan, J.R. Perinatal Outcomes Based on Placental Cord Insertion Site. Am. J. Perinatol 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L.A.; Domínguez-Paz, C.; Ospina, J.F.; Vargas, E.J. Procurement, Processing, and Storage of Human Amniotic Membranes for Implantation Purposes in Non-Healing Pressure Ulcers. Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, N.; Rennekampff, H.O.; Salz, A.K.; Börgel, M. Preparation of human amniotic membrane for transplantation in different application areas. Front. Transplant. 2023, 2, 1152068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros, A.C.V.; Puello, H.R.S.; Lopez-Garcia, J.A.; Bernal-Ballen, A.; Mosquera, D.L.N.; Forero, D.M.M.; Charry, J.S.S.; Bejarano, Y.A.N. Bovine decellularized amniotic membrane: Extracellular matrix as scaffold for mammalian skin. Polymers 2020, 12, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Murillo, A.; Lara-Arias, J.; Leija-Gutiérrez, H.; Franco-Márquez, R.; Moncada-Saucedo, N.K.; Guzmán-López, A.; Vilchez-Cavazos, F.; Garza-Treviño, E.N.; Simental-Mendía, M. The Combination of Decellularized Cartilage and Amniotic Membrane Matrix Enhances the Production of Extracellular Matrix Elements in Human Chondrocytes. Coatings 2024, 14, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuck, R.S.; Graff, J.M.; Bryant, M.R.; Sweet, P.M. Biomechanical characterization of human amniotic membrane preparations for ocular surface reconstruction. Ophthalmic Res. 2004, 36, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

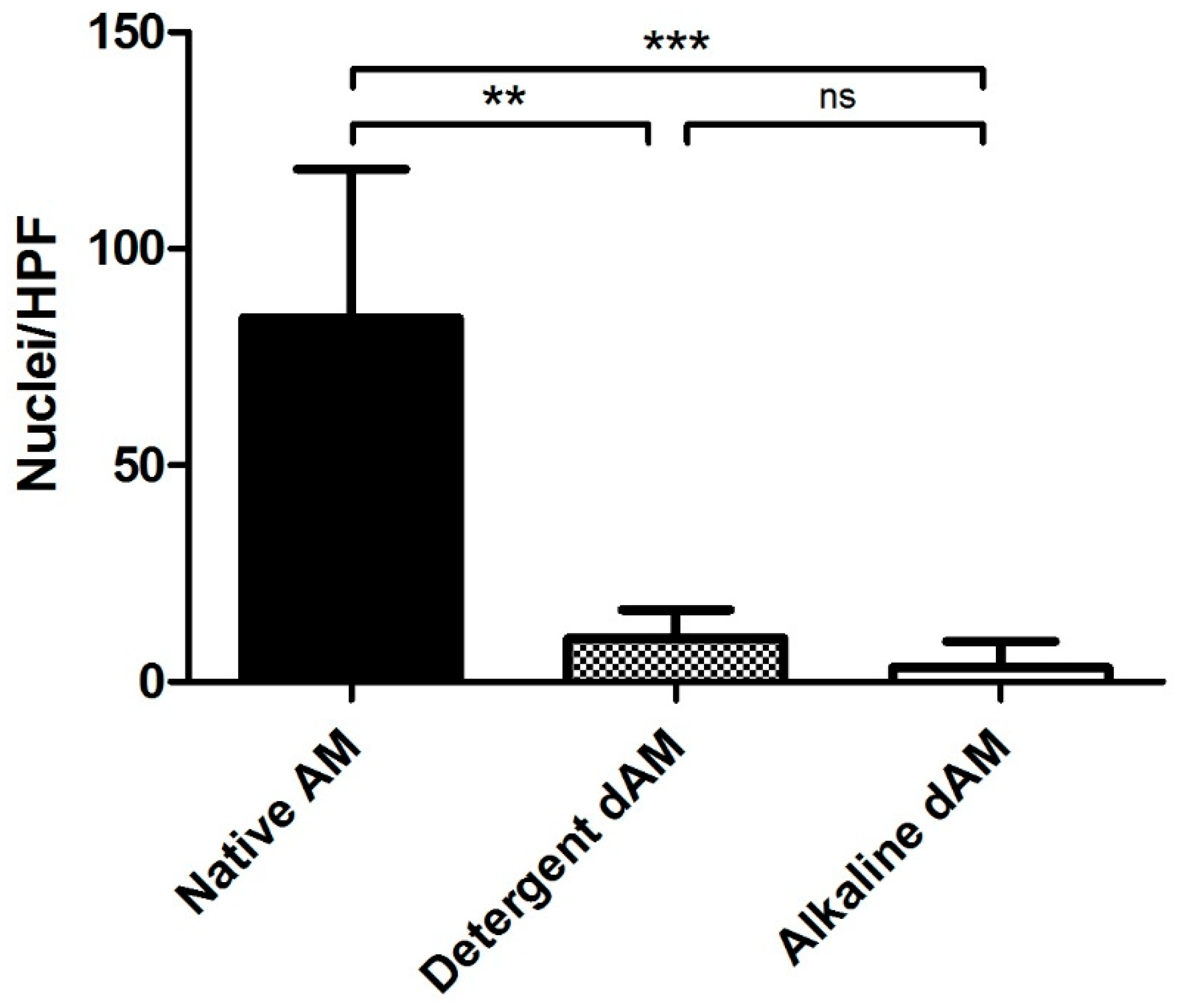

| Experimental Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native AM | Detergent Decellularization | Alkaline Lysis Decellularization | |||

| Nuclei Count | Nuclei Count | % Decellularized | Nuclei Count | % Decellularized | |

| Observer 1 | 88.14 | 0.875 | 99.01 ± 1.53 | 1.99 | 98.01 ± 2.55 |

| Observer 2 | 84.625 | 9.625 | 88.62 ± 7.65 | 1.375 | 98.37 ± 1.77 |

| Observer 3 | 130.75 | 0.375 | 99.69 ± 0.63 | 1.625 | 98.68 ± 1.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

de la Garza Kalife, D.A.; Rojas Murillo, A.; Franco Marquez, R.; Morales Wong, D.L.; Lara Arias, J.; Vilchez Cavazos, J.F.; Leija Gutierrez, H.; Simental Mendía, M.A.; Garza Treviño, E.N. Human Amniotic Membrane Procurement Protocol and Evaluation of a Simplified Alkaline Decellularization Method. Methods Protoc. 2026, 9, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010005

de la Garza Kalife DA, Rojas Murillo A, Franco Marquez R, Morales Wong DL, Lara Arias J, Vilchez Cavazos JF, Leija Gutierrez H, Simental Mendía MA, Garza Treviño EN. Human Amniotic Membrane Procurement Protocol and Evaluation of a Simplified Alkaline Decellularization Method. Methods and Protocols. 2026; 9(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010005

Chicago/Turabian Stylede la Garza Kalife, David A., Antonio Rojas Murillo, Rodolfo Franco Marquez, Diana Laura Morales Wong, Jorge Lara Arias, José Felix Vilchez Cavazos, Hector Leija Gutierrez, Mario A. Simental Mendía, and Elsa Nancy Garza Treviño. 2026. "Human Amniotic Membrane Procurement Protocol and Evaluation of a Simplified Alkaline Decellularization Method" Methods and Protocols 9, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010005

APA Stylede la Garza Kalife, D. A., Rojas Murillo, A., Franco Marquez, R., Morales Wong, D. L., Lara Arias, J., Vilchez Cavazos, J. F., Leija Gutierrez, H., Simental Mendía, M. A., & Garza Treviño, E. N. (2026). Human Amniotic Membrane Procurement Protocol and Evaluation of a Simplified Alkaline Decellularization Method. Methods and Protocols, 9(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010005