Does the Selected Segment Within a Two-Legged Hopping Trial Alter Leg Stiffness and Kinetic Performance Values and Their Variability?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Experimental Procedures

2.3. Double-Legged Hopping Task

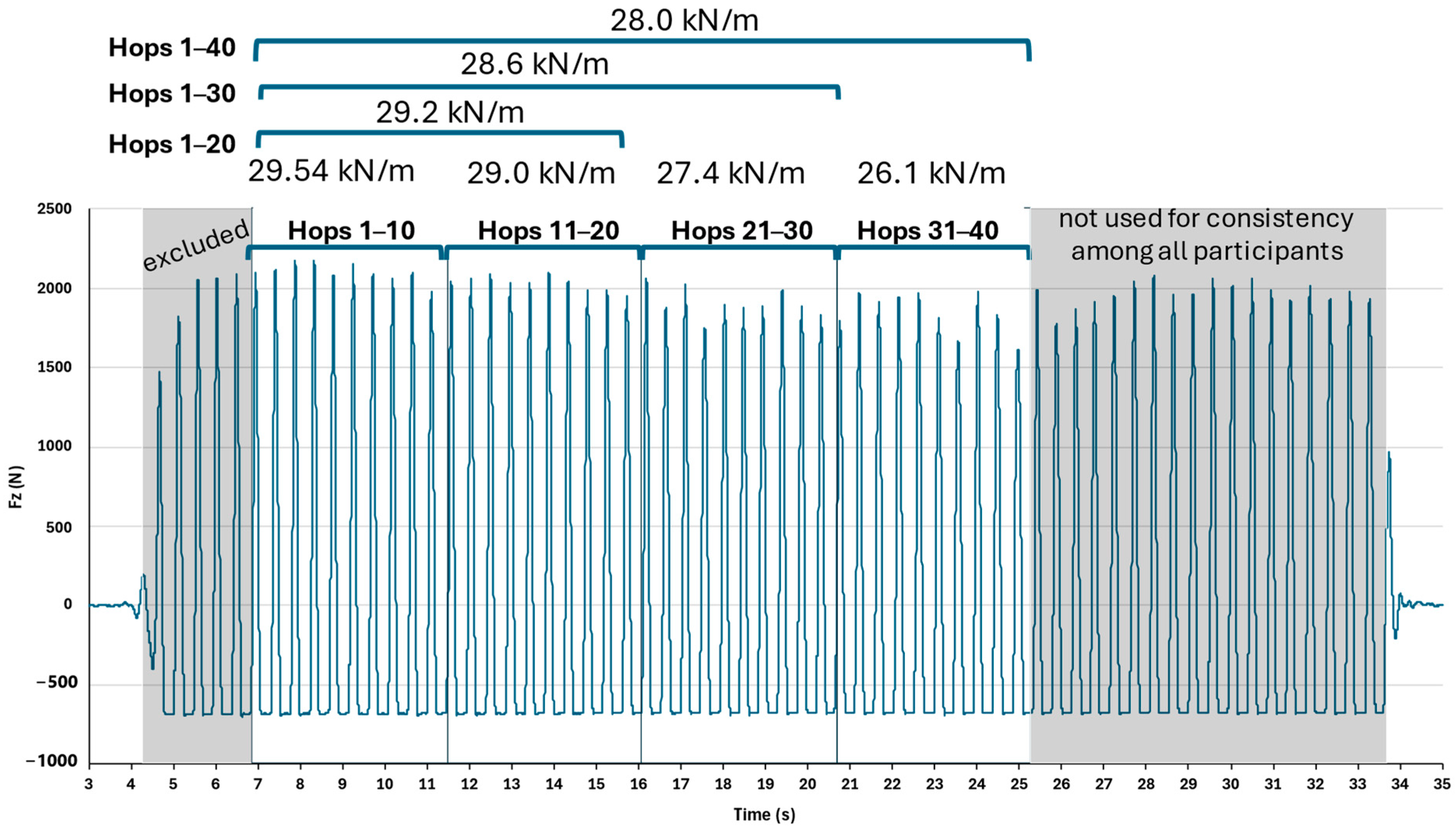

2.4. Hopping Segment Extraction

2.5. Performed Frequency Against the Set Frequency of 130 bpm

2.6. Variable Extraction

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Group X Segment Interaction

3.2. Segment Effect

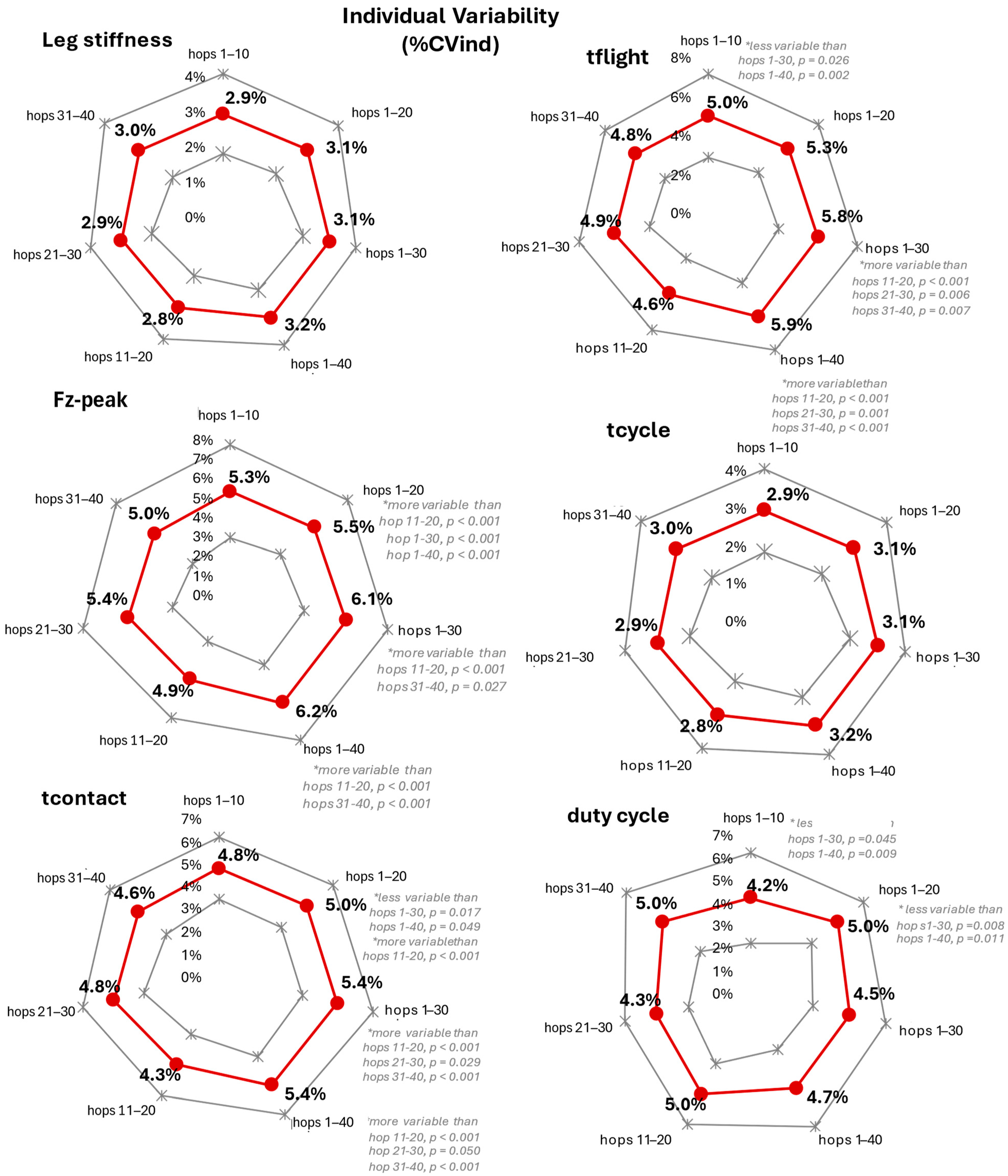

3.3. Trial Segment Effect on Individual Variability (%CVind)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GRF | Ground Reaction Force |

| bmp | beats per minute |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

Appendix A

| Trial Segments | Mean ± SD of Hopping Frequency in bpm (p-Value for One-Sample t-Test with 130 bpm as Test Value) | One-Way ANOVA for Group Effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volley (n = 14) | Basket (n = 14) | Handball (n = 14) | Control (n = 14) | Total (n= 56) | F | Sig. | |

| hops 1–10 | 128.5 ± 3.7 (0.161) | 130.6 ± 3.0 (0.430) | 129.2 ± 2.3 (0.216) | 129.9 ± 3 (0.863) | 129.1 ± 5.0 (0.174) | 1.793 | 0.160 |

| hops 1–20 | 129.0 ± 3.7 (0.182) | 130.9 ± 3.0 (0.275) | 129.0 ± 2.9 (0.221) | 130 ± 2.5 (1.000) | 129.2 ± 4.9 (0.232) | 1.822 | 0.155 |

| hops 1–30 | 129.0 ± 3.9 (0.211) | 131.3 ± 2.7 (0.101) | 129.5 ± 1.9 (0.346) | 129.9 ± 2.2 (0.907) | 129.5 ± 4.6 (0.400) | 2.034 | 0.121 |

| Hops 1–40 | 128.4 ± 4.1 (0.293) | 131.4 ± 2.8 (0.098) | 129.4 ± 1.6 (0.205) | 130.0 ± 2.4 (1.000) | 129.6 ± 4.4 (0.544) | 1.657 | 0.188 |

| hops 11–20 | 127.9 ± 4.7 (0.199) | 131.2 ± 3.4 (0.189) | 128.8 ± 2.9 (0.138) | 129.9 ± 2.7 (0.848) | 129.3 ± 4.8 (0.259) | 1.880 | 0.144 |

| hops 21–30 | 127.8 ± 4.4 (0.287) | 132.0 ± 2.8 (0.061) | 130.2 ± 1.7 (0.748) | 129.1 ± 3.1 (0.314) | 129.8 ± 4.4 (0.711) | 2.335 | 0.085 |

| hops 31–40 | 127.6 ± 5.1 (0.681) | 131.6 ± 3.0 (0.071) | 130.1 ± 2.8 (0.907) | 128.9 ± 6.1 (0.502) | 129.9 ± 5.3 (0.915) | 0.704 | 0.554 |

| Stiffness KN/m | Fz-Peak (BW) | Tcontact (s) | Tflight (s) | Tcycle (s) | Duty Cycle (% Tcycle) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hops 1–10 | 31.08 ± 8.87 | 4.09 ± 0.57 | 0.240 ± 0.037 | 0.228 ± 0.043 | 0.470 ± 0.026 | 51.4 ± 8.2 |

| hops 1–20 | 31.11 ± 8.59 | 4.10 ± 0.57 | 0.239 ± 0.037 | 0.227 ± 0.043 | 0.470 ± 0.024 | 51.4 ± 8.3 |

| hops 1–30 | 31.07 ± 8.60 | 4.08 ± 0.56 | 0.240 ± 0.037 | 0.226 ± 0.042 | 0.468 ± 0.023 | 51.6 ± 8.2 |

| hops 1–40 | 30.64 ± 7.92 | 4.07 ± 0.55 | 0.240 ± 0.036 | 0.225 ± 0.041 | 0.467 ± 0.022 | 51.7 ± 8.0 |

| hops 11–20 | 31.13 ± 8.40 | 4.11 ± 0.58 | 0.239 ± 0.037 | 0.227 ± 0.043 | 0.467 ± 0.022 | 51.4 ± 8.3 |

| hops 21–30 | 31.00 ± 8.72 | 4.03 ± 0.55 | 0.241 ± 0.037 | 0.222 ± 0.040 | 0.465 ± 0.020 | 52.0 ± 7.9 |

| hops 31–40 | 30.65 ± 7.69 | 4.03 ± 0.55 | 0.241 ± 0.035 | 0.222 ± 0.038 | 0.437 ± 0.192 | 52.1 ± 7.7 |

| Group X Segment Interaction | F = 0.795 | F = 1.177 | F = 1.656 | F = 0.844 | F = 0.940 | F = 1.553 |

| p = 0.592 | p = 0.326 | p = 0.142 | p = 0.489 | p = 0.429 | p = 0.177 | |

| Segment Effect across the total of participants (n = 56) | ||||||

| F | 0.572 | 8.406 | 1.417 | 6.037 | 1.394 | 3.612 |

| Sig. (Greenhouse correction for all) | 0.592 | <0.001 * | 0.247 | 0.004 * | 0.243 | 0.034 * (with non-significant pairwise comparisons) |

| Cohen’s d effect size [34] 0.20 = small 0.50 = medium 0.80 = large | 0.20 | 0.78 | 0.32 | 0.66 | 0.32 | 0.51 |

| small | medium to large | small to medium | medium | small to medium | medium | |

| Partial Eta Squared | 0.010 | 0.133 | 0.025 | 0.099 | 0.025 | 0.062 |

| Noncent. Parameter | 1.340 | 16.230 | 2.841 | 11.110 | 1.415 | 6.666 |

| Observed Power | 0.151 | 0.956 | 0.299 | 0.855 | 0.214 | 0.632 |

| Pairwise Segment Comparisons | ns for all | 1–20 > 1–30 >1–40 >21–30 | ns for all | 1–10 > 1–30 >1–40 1–20 > 1–30 >1–40 | ns for all | ns for all |

| KN/m (%) | Fz-Peak (%) | Tcontact (%) | Tflight (%) | Tcycle (%) | Duty Cycle (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hops 1–10 | 8.2 ± 2.0 | 5.4 ± 2.4 | 4.8 ± 1.4 | 5.0 ± 2.1 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 3.8 ± 1.5 |

| hops 1–20 | 8.2 ± 2.1 | 5.5 ± 2.3 | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 2.0 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 3.9 ± 1.3 |

| hops 1–30 | 8.7 ± 2.0 | 6.1 ± 2.2 | 5.4 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 2.1 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 1.5 |

| hops 1–40 | 8.6 ± 2.0 | 6.2 ± 2.1 | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 5.9 ± 2.0 | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 4.4 ± 1.3 |

| hops 11–20 | 7.1 ± 2.5 | 4.7 ± 2.2 | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 4.6 ± 2.0 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 3.3 ± 1.2 |

| hops 21–30 | 8.6 ± 3.0 | 5.4 ± 2.4 | 4.8 ± 1.4 | 4.9 ± 1.9 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 1.4 |

| hops 31–40 | 7.4 ± 2.2 | 5.0 ± 2.6 | 4.6 ± 1.6 | 4.8 ± 2.0 | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 3.4 ± 1.3 |

| Group X Segment Interaction | F = 8.928 | F = 2.673 | F = 1.492 | F = 0.639 | F = 1.177 | F = 0.975 |

| p < 0.001 | p = 0.035 | p = 0.131 | p = 0.801 | p = 0.279 | p = 0.471 | |

| Segment Effect across the total of participants (n = 56) | ||||||

| F | 0.784 | 6.648 | 8.182 | 7.955 | 1.222 | 12.803 |

| Sig. (Greenhouse correction for all) | 0.382 | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.303 | <0.001 * |

| Cohen’s d effect size [34] 0.20 = small 0.50 = medium 0.80 = large | 0.20 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.97 |

| small | large | large | large | medium to small | large | |

| Partial Eta Squared | 0.014 | 0.110 | 0.129 | 0.126 | 0.022 | 0.189 |

| Noncent. Parameter | 0.796 | 19.718 | 32.413 | 30.820 | 3.851 | 47.485 |

| Observed Power | 0.141 | 0.970 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.332 | 1.000 |

| ns for all | ns for all | 1–20 > 11–20 >21–30 >31–40 1–30 > 11–20 >21–30 >31–40 1–40 >11–20 >21–30 >31–40 | 1–10 < 1–30 <1–40 1–30 > 11–20 >21–30 >31–40 1–40 > 11–20 >21–30 >31–40 | ns for all | 1–10 < 1–30 <1–40 1–20 < 1–30 <1–40 1–30 > 11–20 >21–30 >31–40 1–40 > 11–20 >21–30 >31–40 | |

References

- Blickhan, R. The spring-mass model for running and hopping. J. Biomech. 1989, 22, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, T.A.; Cheng, G.C. The mechanics of running: How does stiffness couple with speed? J. Biomech. 1990, 23, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, S.J.; McMahon, J. Lower limb mechanical properties: Determining factors and implications for performance. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazier, J.; Maloney, S.; Bishop, C.; Read, P.J.; Turner, A.N. Lower extremity stiffness: Considerations for testing, performance enhancement, and injury risk. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.J.; Crowell, H.P.; McClay Davis, I. Lower extremity stiffness: Implications for performance and injury. Clin. Biomech. 2003, 18, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalleau, G.; Bepearlli, A.; Viale, F.; Lacour, J.R.; Bourdin, M. A simple method for field measurements of leg stiffness in hopping. Int. J. Sports Med. 2004, 25, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbüken, I.; Yurdalan, S.U.; Savelberg, H.; Meijer, K. Gender specific strategies in demanding hopping conditions. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2009, 8, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Farley, C.T.; Houdijk, H.H.; Van Strien, C.; Louie, M. Mechanism of leg stiffness adjustment for hopping on surfaces of different stiffnesses. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 85, 1044–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobara, H.; Inoue, K.; Omuro, K.; Muraoka, T.; Kanosue, K. Determinant of leg stiffness during hopping is frequency-dependent. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 2011, 111, 2195–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobara, H.; Inoue, K.; Kanosue, K. Effect of hopping frequency on bilateral differences in leg stiffness. J. Appl. Biomech. 2013, 29, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, Y.H. Leg Stiffness from landing methods of hopping. In Proceedings of the 6th World Congress of Biomechanics (WCB 2010), Singapore, 1–6 August 2010; IFMBE Proceedings. Lim, C.T., Goh, J.C.H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; Volume 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padua, D.A.; Carcia, C.R.; Arnold, B.L.; Granata, K.P. Gender differences in leg stiffness and stiffness recruitment strategy during two-legged hopping. J. Mot. Behav. 2005, 37, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, C.T.; Morgenroth, D.C. Leg stiffness primarily depends on ankle stiffness during human hopping. J. Biomech. 1999, 32, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granata, K.P.; Padua, D.A.; Wilson, S.E. Gender differences in active musculoskeletal stiffness. Part. II. Quantification of leg stiffness during functional hopping tasks. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2002, 12, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maloney, S.J.; Fletcher, I.M.; Richards, J. A comparison of methods to determine bilateral asymmetries in vertical leg stiffness. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 34, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuriyama, K.; Takeshita, D. Leg stiffness adjustment during hopping by dynamic interaction between the muscle and tendon of the medial gastrocnemius. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 138, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, C.T.; Farley, C.T. Human hopping on damped surfaces: Strategies for adjusting leg mechanics. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 1741–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, M.; Kurihara, T.; Isaka, T. Bilateral deficit of spring-like behaviour during hopping in sprinters. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 118, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobara, H.; Inoue, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ogata, T. A comparison of computation methods for leg stiffness during hopping. J. Appl. Biomech. 2014, 30, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresi, M.P.; Bradshaw, E.J.; Greene, D.A.; Naughton, G.A. The impact of data reduction on the intra-trial reliability of a typical measure of lower limb musculoskeletal stiffness. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, N.; Decker, L.M. Human movement variability, nonlinear dynamics, and pathology: Is there a connection? Hum. Mov. Sci. 2011, 30, 869–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, R.; Wheat, J.; Robins, M. Is movement variability important for sports biomechanists? Sports Biomech. 2007, 6, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajachandrakumar, R.; Mann, J.; Schinkel-Ivy, A.; Mansfield, A. Exploring the relationship between stability and variability of the centre of mass and centre of pressure. Gait Posture 2018, 63, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Emmerik, R.E.; van Wegen, E.E. On variability and stability in human movement. J. Appl. Biomech. 2000, 16, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repp, B.H.; Su, Y.H. Sensorimotor synchronization: A review of recent research (2006–2012). Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2013, 20, 403–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varlet, M.; Williams, R.A.; Keller, P.E. Effects of pitch and tempo of auditory rhythms on spontaneous movement entrainment and stabilisation. Psychol. Res. 2018, 84, 568–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobara, H.; Kanosue, K.; Suzuki, S. Changes in muscle activity with increase in leg stiffness during hopping. Neurosci. Lett. 2007, 418, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, J.B.; Dalleau, G.; Kyröläinen, H.; Jeannin, T.; Belli, A. A simple method for measuring stiffness during running. J. Appl. Biomech. 2005, 21, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranjić, M.; Janzen, T.B.; Vukšić, N.; Thaut, M. From sound to movement: Mapping the neural mechanisms of auditory–motor entrainment and synchronization. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaradan, S.; Peretz, I.; Keller, P.E. Individual differences in rhythmic cortical entrainment correlate with predictive behavior in sensorimotor synchronization. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, C.T.; Blickhan, R.; Saito, J.; Taylor, C.R. Hopping frequency in humans: A test of how springs set stride frequency in bouncing gaits. J. Appl. Physiol. 1991, 71, 2127–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.W.; Bradshaw, E.J.; Kemp, J.; Clark, R.A. The interday reliability of ankle, knee, leg, and vertical musculoskeletal stiffness during hopping and overground running. J. Appl. Biomech. 2013, 29, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cavagna, G.A. Force platforms as ergometers. J. Appl. Physiol. 1975, 39, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rousanoglou, E.N.; Boudolos, K.D. Rhythmic performance during a whole body movement: Dynamic analysis of force-time curves. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2006, 25, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borzelli, D.; Vieira, T.M.M.; Botter, A.; Gazzoni, M.; Lacquaniti, F.; d’Avella, A. Synaptic inputs to motor neurons underlying muscle coactivation for functionally different tasks have different spectral characteristics. J. Neurophysiol. 2024, 131, 1126–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, M.; Chelli, F.; Frigo, C. Changes in the excitability of soleus muscle short latency stretch reflexes during human hopping after 4 weeks of hopping training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1998, 78, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyhre-Poulsen, P.; Simonsen, E.B.; Voigt, M. Dynamic control of muscle stiffness and H reflex modulation during hopping and jumping in man. J. Physiol. 1991, 437, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuitunen, S.; Ogiso, K.; Komi, P.V. Leg and joint stiffness in human hopping. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2011, 21, e159–e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, H.; Quan, W.; Ma, X.; Chon, T.E.; Fernandez, J.; Gusztav, F.; Kovács, A.; Baker, J.S.; Gu, Y. New insights optimize landing strategies to reduce lower limb injury risk. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2024, 5, 0126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M. Leg joint mechanics when hopping at different frequencies. J. Appl. Biomech. 2021, 37, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte, A.; Nardello, F.; Zamparo, P. Mechanical advantage and joint function of the lower limb during hopping at different frequencies. J. Biomech. 2021, 118, 110294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, M.; Keppler, V.; Seyfarth, A.; Blickhan, R. Human leg design: Optimal axial alignment under constraints. J. Math. Biol. 2004, 48, 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvitella, A.M.; Foster, K.L. On the variability and dependence of human leg stiffness across strides during running and some consequences for the analysis of locomotion data. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 230597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.D.; Collins, D.R.; Bingham, G.P. Perceptual Coupling in Rhythmic Movement Coordination: Stable Perception Leads to Stable Action. Exp. Brain Res. 2005, 164, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobara, H.; Kato, E.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ogata, T. Sex differ ences in relationship between passive ankle stiffness and leg stiffness during hopping. J. Biomech. 2012, 45, 2750–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, D.P.; Farley, C.T. Interaction of leg stiffness and surfaces stiffness during human hopping. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997, 82, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struzik, A.; Zawadzki, J.; Rokita, A.; Pietraszewski, B. Application of an Accelerometric System for Determination of Stiffness during a Hopping Task. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2020, 2020, 3826503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranavolo, A.; Don, R.; Cacchio, A.; Serrao, M.; Paoloni, M.; Mangone, M.; Santilli, V. Comparison between kinematic and kinetic methods for computing the vertical displacement of the center of mass during human hopping at different frequencies. J. Appl. Biomech. 2008, 24, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Komi, P.V. Stretch-shortening cycle: A powerful model to study normal and fatigued muscle. J. Biomech. 2000, 33, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fábrica, G. Effects of power training in mechanical stiffness of the lower limbs in soccer players. Rev. Andal. Med. Deporte 2015, 12, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millett, E.L.; Moresi, M.P.; Watsford, M.L.; Taylor, P.G.; Greene, D.A. Variations in lower body stiffness during sports-specific tasks in well-trained female athletes. Sports Biomech. 2021, 20, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedo, B.L.S.; Cesar, G.M.; Andrade, V.L.; Moura, F.A.; Palucci Vieira, L.H.; Aquino, R.; Domingos, M.B.; Santiago, P.R.P. Landing mechanics of basketball and volleyball athletes: A kinematic approach. Hum. Mov. 2022, 23, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, J.; Moreno-Doutres, D.; Coma, J.; Cook, M.; Buscà, B. Anthropometric and fitness profile of high-level basketball, handball and volleyball players. Rev. Andal. Med. Deport. 2018, 11, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacoff, A.; Kaelin, X.; Stuessi, E. The impact in landing after a volleyball block. In Biomechanics XI-B; Free University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 694–700. [Google Scholar]

- Skazalski, C.; Whiteley, R.; Bahr, R. High jump demands in professional volleyball-large variability exists between players and player positions. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28, 2293–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struzik, A.; Pietraszewski, B.; Zawadzki, J. Biomechanical analysis of the jump shot in basketball. J. Hum. Kinet. 2014, 42, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svilar, L.; Castellano, J.; Jukic, I.; Casamichana, D. Positional differences in elite basketball: Selecting appropriate training-load measures. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousanoglou, E.; Noutsos, K.; Bayios, I.; Boudolos, K. Ground reaction forces and throwing performance in elite and novice players in two types of handball shot. J. Hum. Kinet. 2014, 40, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Haro, P.J.; Gómez-Carmona, C.D.; Bastida-Castillo, A.; Rojas-Valverde, D.; Gómez-López, M.; Pino-Ortega, J. Analysis of playing position and matchstatus-related differences in external load demands on amateur handball:a case study. Rev. Bras. Cineantropometria Desempenho Hum. 2020, 22, e71427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, C.T.; Gonzalez, O. Leg stiffness and stride frequency in human running. J. Biomech. 1996, 29, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tata, O.; Emmanouil, A.; Barzouka, K.; Boudolos, K.; Rousanoglou, E. Does the Selected Segment Within a Two-Legged Hopping Trial Alter Leg Stiffness and Kinetic Performance Values and Their Variability? Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060152

Tata O, Emmanouil A, Barzouka K, Boudolos K, Rousanoglou E. Does the Selected Segment Within a Two-Legged Hopping Trial Alter Leg Stiffness and Kinetic Performance Values and Their Variability? Methods and Protocols. 2025; 8(6):152. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060152

Chicago/Turabian StyleTata, Ourania, Analina Emmanouil, Karolina Barzouka, Konstantinos Boudolos, and Elissavet Rousanoglou. 2025. "Does the Selected Segment Within a Two-Legged Hopping Trial Alter Leg Stiffness and Kinetic Performance Values and Their Variability?" Methods and Protocols 8, no. 6: 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060152

APA StyleTata, O., Emmanouil, A., Barzouka, K., Boudolos, K., & Rousanoglou, E. (2025). Does the Selected Segment Within a Two-Legged Hopping Trial Alter Leg Stiffness and Kinetic Performance Values and Their Variability? Methods and Protocols, 8(6), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060152