New Approach for Targeting Small-Molecule Candidates for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Databases

- O02828 Capra hircus;

- P10637 Mus musculus;

- P19332 Rattus norvegicus;

- P29172 Bos taurus;

- P57786 Macaca mulatta;

- Q5S6V2 Pongo pygmaeus;

- Q5YCV9 Hylobates lar;

- Q5YCW0 Gorilla gorilla gorilla;

- Q5YCW1 Pan troglodytes;

- Q6TS35 Spermophilus citellus;

- Q9MYX8 Papio hamadryas.

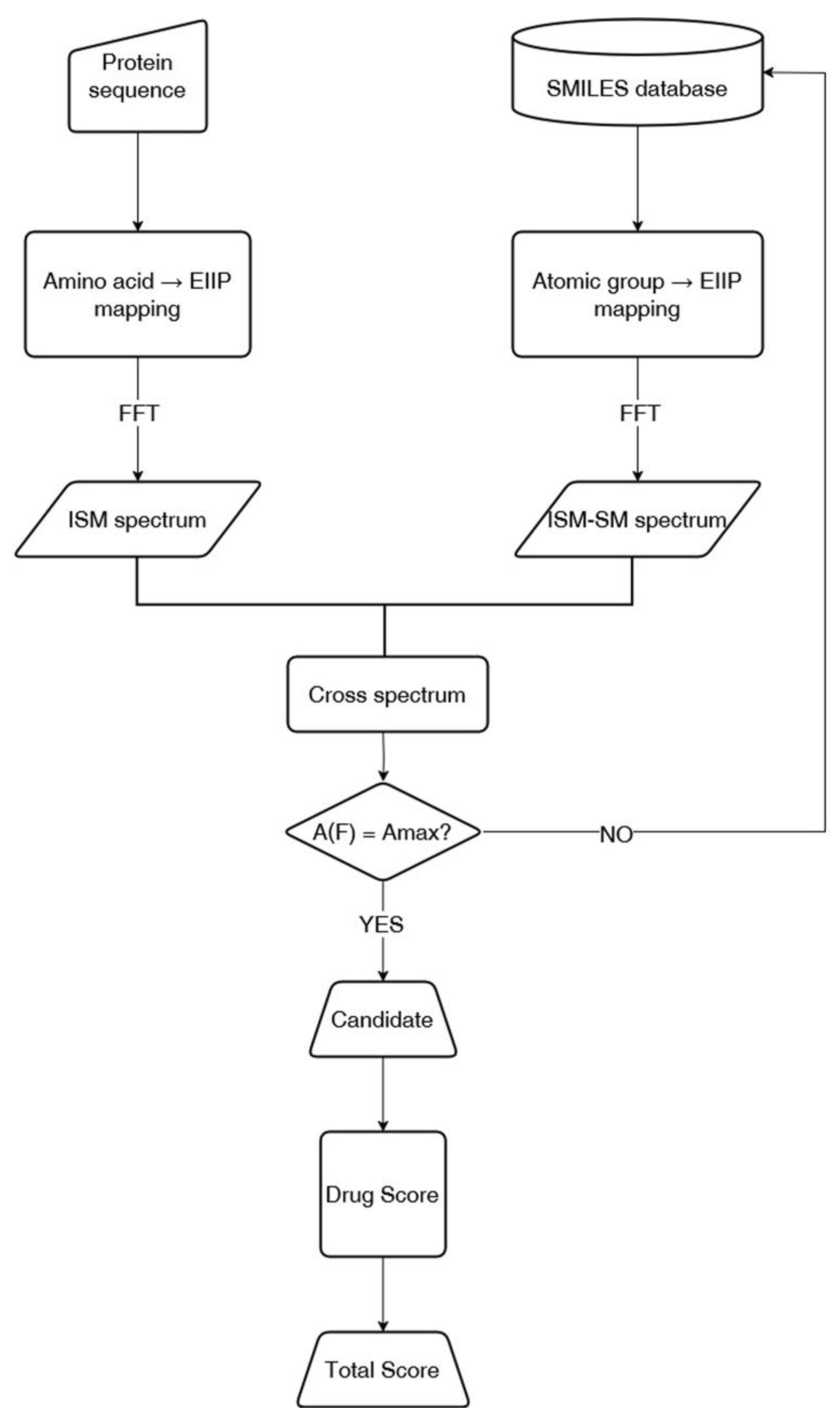

2.2. ISM-SM Method

- Numerical Encoding of Protein Sequences: The primary amino acid sequence of the protein is converted into a numerical series by assigning each residue its corresponding electron–ion interaction potential (EIIP) value.

- Numerical Encoding of Small Molecules: The molecular structure of a small molecule, represented in SMILES notation, is translated into a numerical sequence by mapping each atomic group to its EIIP value.

- Informational Spectrum Calculation: The numerical sequences obtained for the protein and small molecules are transformed into informational spectra (IS) using the discrete Fourier transform (DFT). This process decomposes the sequences into frequencies and amplitudes, revealing periodicities corresponding to structural and functional motifs.

- Cross-Spectrum (CS) Analysis: The interaction potential between the protein and small molecules is assessed by calculating the cross-spectrum, which identifies shared frequencies in their respective IS profiles. These common frequencies indicate potential sites of interaction or functional correlation.

2.3. Drug Score Calculation

2.4. Pharmacokinetics Predictions

2.5. Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. DrugBank Candidates

3.2. COCONUT Database Candidates

3.3. Pharmacokinetic Properties of the Selected Compounds

k-Means Clustering

3.4. Comparison to the Martini-IDP Forcefield

3.5. Comparison to Ensemble Docking Results

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IDP | Intrinsically disordered protein |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin gallate |

| MD | Molecular Dynamics |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| SPR | Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| ISM-SM | Informational Spectrum Method for Small Molecules |

| HTPS | High-Throughput Screening |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| EIIP | Electron Ion Interaction Potential |

| DFT | Discrete Fourier Transformation |

| IS | Informational Spectra |

| CS | Cross Spectrum |

| MW | Molecular Weight |

| dS | Drug Score |

| S/N | Signal-to-Noise ratio |

| MTBD | Microtubule-Binding |

| Aβ | Amyloid-Beta |

| PKC | Protein Kinase C |

| GSK | Glycogen Synthase Kinase |

| CWT | Continuous Wavelet Transform |

References

- Uversky, V.N. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins and Their (Disordered) Proteomes in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.E.; Dyson, H.J. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins in Cellular Signalling and Regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieschke, J.; Russ, J.; Friedrich, R.P.; Ehrnhoefer, D.E.; Wobst, H.; Neugebauer, K.; Wanker, E.E. EGCG Remodels Mature α-Synuclein and Amyloid-β Fibrils and Reduces Cellular Toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 7710–7715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoury, E.; Pickhardt, M.; Gajda, M.; Biernat, J.; Mandelkow, E.; Zweckstetter, M. Mechanistic Basis of Phenothiazine-Driven Inhibition of Tau Aggregation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013, 52, 3511–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Mistry, H.; Bihani, S.C.; Mukherjee, S.P.; Gupta, G.D. Unveiling Potential Inhibitors Targeting the Nucleocapsid Protein of SARS-CoV-2: Structural Insights into Their Binding Sites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 133167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verburgt, J.; Zhang, Z.; Kihara, D. Multi-Level Analysis of Intrinsically Disordered Protein Docking Methods. Methods 2022, 204, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, A.; Sisk, T.R.; Robustelli, P. Ensemble Docking for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins 2025. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 6847–6860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzas, P.; Brotzakis, Z.F.; Sarimveis, H. Small Molecules Targeting the Structural Dynamics of AR-V7 Partially Disordered Proteins Using Deep Ensemble Docking. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2025, 21, 4898–4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, K.N.; Chavda, D.; Manna, M. Molecular Docking of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: Challenges and Strategies. In Pro-tein-Protein Docking; Methods in Molecular Biology; Kaczor, A.A., Ed.; Springer US: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 2780, pp. 165–201. ISBN 978-1-0716-3984-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, H.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Lai, L. Targeting Intrinsically Disordered Proteins at the Edge of Chaos. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chong, B.; Sun, Z.; Ruan, H.; Yang, Y.; Song, P.; Liu, Z. More Is Simpler: Decomposition of LIGAND-BINDING Affinity for Proteins Being Disordered. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, e4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apicella, A.; Marascio, M.; Colangelo, V.; Soncini, M.; Gautieri, A.; Plummer, C.J.G. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Intrinsically Disordered Protein Amelogenin. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2017, 35, 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrev, V.S.; Fred, L.M.; Gerhart, K.P.; Metallo, S.J. Characterization of the Binding of Small Molecules to Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 611, pp. 677–702. ISBN 978-0-12-815649-0. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, G.T.; Shukla, V.K.; Figueiredo, A.M.; Hansen, D.F. Picosecond Dynamics of a Small Molecule in Its Bound State with an Intrinsically Disordered Protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 2319–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, G.T.; Sormanni, P.; Vendruscolo, M. Targeting Disordered Proteins with Small Molecules Using Entropy. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Nieto, P.; Pérez, A.; De Fabritiis, G. Small Molecule Modulation of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 5003–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.; Yu, C.; Niu, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Xiong, R.; Sun, Q.; Jin, C.; Liu, Y.; et al. Computational Strategy for In-trinsically Disordered Protein Ligand Design Leads to the Discovery of P53 Transactivation Domain I Binding Compounds That Activate the P53 Pathway. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 3004–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vagrys, D.; Davidson, J.; Chen, I.; Hubbard, R.E.; Davis, B. Exploring IDP–Ligand Interactions: Tau K18 as a Test Case. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Brasnett, C.; Borges-Araújo, L.; Souza, P.C.T.; Marrink, S.J. Martini3-IDP: Improved Martini 3 Force Field for Disor-dered Proteins. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadourakis, M.; Cournia, Z.; Mey, A.S.J.S.; Michel, J. Comparison of Methodologies for Absolute Binding Free Energy Cal-culations of Ligands to Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2024, 20, 9699–9707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, J.; Cuchillo, R. The Impact of Small Molecule Binding on the Energy Landscape of the Intrinsically Disordered Protein C-Myc. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiong, R.; Lai, L. Rational Drug Design Targeting Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2023, 13, e1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appadurai, R.; Koneru, J.K.; Bonomi, M.; Robustelli, P.; Srivastava, A. Clustering Heterogeneous Conformational Ensembles of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins with T-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2023, 19, 4711–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattuparambil, A.A.; Chaurasia, D.K.; Shekhar, S.; Srinivasan, A.; Mondal, S.; Aduri, R.; Jayaram, B. Exploring Chemical Space for “Druglike” Small Molecules in the Age of AI. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1553667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lama, D.; Vosselman, T.; Sahin, C.; Liaño-Pons, J.; Cerrato, C.P.; Nilsson, L.; Teilum, K.; Lane, D.P.; Landreh, M.; Arsenian Henriksson, M. A Druggable Conformational Switch in the C-MYC Transactivation Domain. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzi, N.L.; Ying, J.; Torchia, D.A.; Clore, G.M. Kinetics of Amyloid β Monomer-to-Oligomer Exchange by NMR Relaxation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 9948–9951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMasi, J.A.; Grabowski, H.G.; Hansen, R.W. Innovation in the Pharmaceutical Industry: New Estimates of R&D Costs. J. Health Econ. 2016, 47, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sencanski, M.; Sumonja, N.; Perovic, V.; Glisic, S.; Veljkovic, N.; Veljkovic, V. Application of Information Spectrum Method on Small Molecules and Target Recognition. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.02713v3. [Google Scholar]

- Sencanski, M.; Perovic, V.; Pajovic, S.B.; Adzic, M.; Paessler, S.; Glisic, S. Drug Repurposing for Candidate SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors by a Novel in Silico Method. Molecules 2020, 25, 3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sencanski, M.; Perovic, V.; Milicevic, J.; Todorovic, T.; Prodanovic, R.; Veljkovic, V.; Paessler, S.; Glisic, S. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 Papain-like Protease (PLpro) Inhibitors Using Combined Computational Approach. Chem. Open 2022, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Đukić, I.; Kaličanin, N.; Sencanski, M.; Pajovic, S.B.; Milicevic, J.; Prljic, J.; Paessler, S.; Prodanović, R.; Glisic, S. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with Vitamin C, L-Arginine and a Vitamin C/L-Arginine Combination. Front. Biosci. 2023, 28, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protić, S.; Kaličanin, N.; Sencanski, M.; Prodanović, O.; Milicevic, J.; Perovic, V.; Paessler, S.; Prodanović, R.; Glisic, S. In Silico and In Vitro Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro with Gramicidin D. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protić, S.; Crnoglavac Popović, M.; Kaličanin, N.; Prodanović, O.; Senćanski, M.; Milićević, J.; Stevanović, K.; Perović, V.; Paessler, S.; Prodanović, R.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 PLpro Inhibition: Evaluating in Silico Repurposed Fidaxomicin’s Antiviral Activity Through In Vitro Assessment. Chem. Open 2024, 13, e202400091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thal, D.R.; Tomé, S.O. The Central Role of Tau in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Neurofibrillary Tangle Maturation to the Induction of Cell Death. Brain Res. Bull. 2022, 190, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The UniProt Consortium; Bateman, A.; Martin, M.-J.; Orchard, S.; Magrane, M.; Adesina, A.; Ahmad, S.; Bowler-Barnett, E.H.; Bye-A-Jee, H.; Carpentier, D.; et al. UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D609–D617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Feunang, Y.D.; Guo, A.C.; Lo, E.J.; Marcu, A.; Grant, J.R.; Sajed, T.; Johnson, D.; Li, C.; Sayeeda, Z.; et al. DrugBank 5.0: A Major Update to the DrugBank Database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D1074–D1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, V.; Rajan, K.; Kanakam, S.R.S.; Sharma, N.; Weißenborn, V.; Schaub, J.; Steinbeck, C. COCONUT 2.0: A Comprehensive Overhaul and Curation of the Collection of Open Natural Products Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D634–D643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veljković, V.; Cosić, I. A Novel Method of Protein Analysis for Prediction of Biological Function: Application to Tumor Toxins. Cancer Biochem. Biophys. 1987, 9, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lechelon, M.; Meriguet, Y.; Gori, M.; Ruffenach, S.; Nardecchia, I.; Floriani, E.; Coquillat, D.; Teppe, F.; Mailfert, S.; Marguet, D.; et al. Experimental Evidence for Long-Distance Electrodynamic Intermolecular Forces. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veljković, V. The Dependence of the Fermi Energy on the Atomic Number. Phys. Lett. A 1973, 45, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veljković, V.; Slavić, I. Simple General-Model Pseudopotential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1972, 29, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, T.; Freyss, J.; Von Korff, M.; Rufener, C. DataWarrior: An Open-Source Program for Chemistry Aware Data Visuali-zation and Analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, D.E.V.; Blundell, T.L.; Ascher, D.B. pkCSM: Predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Properties Using Graph-Based Signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 4066–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaković, S.; Senćanski, M.; Perović, V.; Stevanović, K.; Prodić, I. Bioinformatic Selection of Mannose-Specific Lectins from Allium Genus as SARS-CoV-2 Inhibitors Analysing Protein–Protein Interaction. Life 2025, 15, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, S.C.; Iaccarino, L.; Pontecorvo, M.J.; Fleisher, A.S.; Lu, M.; Collins, E.C.; Devous, M.D. A Review of the Flortaucipir Literature for Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of Tau Neurofibrillary Tangles. Brain Commun. 2023, 6, fcad305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo, L.E.; Alzate-Morales, J.; Saavedra, I.N.; Davies, P.; Maccioni, R.B. Selective Interaction of Lansoprazole and Astemizole with Tau Polymers: Potential New Clinical Use in Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. JAD 2010, 19, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imtiaz, A.; Shimonaka, S.; Uddin, M.N.; Elahi, M.; Ishiguro, K.; Hasegawa, M.; Hattori, N.; Motoi, Y. Selection of Lansoprazole from an FDA-Approved Drug Library to Inhibit the Alzheimer’s Disease Seed-Dependent Formation of Tau Aggregates. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1368291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustke, N.; Trinczek, B.; Biernat, J.; Mandelkow, E.-M.; Mandelkow, E. Domains of Tau Protein and Interactions with Micro-tubules. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 9511–9522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shi, J.; Chu, D.; Hu, W.; Guan, Z.; Gong, C.-X.; Iqbal, K.; Liu, F. Relevance of Phosphorylation and Truncation of Tau to the Etiopathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarini, A.; Armato, U.; Liu, D.; Dal Prà, I. Calcium-Sensing Receptors of Human Neural Cells Play Crucial Roles in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-F.; Jhao, Y.-T.; Chiu, C.-H.; Sun, L.-H.; Chou, T.-K.; Shiue, C.-Y.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Ma, K.-H. Bezafibrate Exerts Neuropro-tective Effects in a Rat Model of Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Yu, J.-T.; Zhu, X.-C.; Zhang, Q.-Q.; Cao, L.; Wang, H.-F.; Tan, M.-S.; Gao, Q.; Qin, H.; Zhang, Y.-D.; et al. Temsirolimus Attenuates Tauopathy in Vitro and in Vivo by Targeting Tau Hyperphosphorylation and Autophagic Clearance. Neurophar-macology 2014, 85, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Yu, J.-T.; Zhu, X.-C.; Tan, M.-S.; Wang, H.-F.; Cao, L.; Zhang, Q.-Q.; Shi, J.-Q.; Gao, L.; Qin, H.; et al. Temsirolimus Promotes Autophagic Clearance of Amyloid-β and Provides Protective Effects in Cellular and Animal Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2014, 81, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Agrawal, M.; Mahendiratta, S.; Kumar, S.; Arora, S.; Joshi, R.; Prajapat, M.; Sarma, P.; Prakash, A.; Chopra, K.; et al. Everolimus: A Potential Therapeutic Agent Targeting PI3K/Akt Pathway in Brain Insulin System Dysfunction and Associated Neurobehavioral Deficits. Fundamemntal Clin. Pharma 2021, 35, 1018–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassano, T.; Magini, A.; Giovagnoli, S.; Polchi, A.; Calcagnini, S.; Pace, L.; Lavecchia, M.A.; Scuderi, C.; Bronzuoli, M.R.; Ruggeri, L.; et al. Early Intrathecal Infusion of Everolimus Restores Cognitive Function and Mood in a Murine Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 311, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admane, N.; Grover, A. A Neurohypophyseal Hormone Analog Modulates the Amyloid Aggregation of Human Prion Protein. Biophys. J. 2022, 121, 56a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Dexheimer, T.; Sui, D.; Hovde, S.; Deng, X.; Kwok, R.; Bochar, D.A.; Kuo, M.-H. Hyperphosphorylated Tau Aggregation and Cytotoxicity Modulators Screen Identified Prescription Drugs Linked to Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitive Functions. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, N.H.; El-Tanbouly, D.M.; El Sayed, N.S.; Khattab, M.M. Roflumilast Ameliorates Cognitive Deficits in a Mouse Model of Amyloidogenesis and Tauopathy: Involvement of Nitric Oxide Status, Aβ Extrusion Transporter ABCB1, and Reversal by PKA Inhibitor H89. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 111, 110366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.-Y.; Xu, J.-H.; Lo, Y.M.; Tu, R.-S.; Wu, J.S.-B.; Huang, W.-C.; Shen, S.-C. Alleviative Effect of Alpha-Lipoic Acid on Cognitive Impairment in High-Fat Diet and Streptozotocin-Induced Type 2 Diabetic Rats. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 774477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, B.; Berkay Yılmaz, Y.; Antika, G.; Boyunegmez Tumer, T.; Fawzi Mahomoodally, M.; Lobine, D.; Akram, M.; Riaz, M.; Capanoglu, E.; Sharopov, F.; et al. Insights on the Use of α-Lipoic Acid for Therapeutic Purposes. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, S.M.; Romeiro, C.F.R.; Rodrigues, C.A.; Cerqueira, A.R.L.; Monteiro, M.C. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Al-pha-Lipoic Acid: Beneficial or Harmful in Alzheimer’s Disease? Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Singh, T.G.; Dahiya, R.S.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. α-Lipoic Acid, an Organosulfur Biomolecule a Novel Therapeutic Agent for Neurodegenerative Disorders: An Mechanistic Perspective. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 1853–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Hu, F.; Luo, F.; Huang, X.; Li, X.; Xing, S.; Long, D. The Neuroprotective Effects of Alpha-lipoic Acid on an Experimental Model of Alzheimer’s Disease in PC12 Cells. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2022, 42, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, X.; Hu, F.; Hu, Z.; Luo, F.; Li, X.; Xing, S.; Sun, L.; Long, D. Neuroprotective Effect of α-Lipoic Acid against Aβ25–35-Induced Damage in BV2 Cells. Molecules 2023, 28, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zara, S.; De Colli, M.; Rapino, M.; Pacella, S.; Nasuti, C.; Sozio, P.; Di Stefano, A.; Cataldi, A. Ibuprofen and Lipoic Acid Conjugate Neuroprotective Activity Is Mediated by Ngb/Akt Intracellular Signaling Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease Rat Model. Gerontology 2013, 59, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarini-Gakiye, E.; Vaezi, G.; Parivar, K.; Sanadgol, N. Age and Dose-Dependent Effects of Alpha-Lipoic Acid on Human Mi-crotubule- Associated Protein Tau-Induced Endoplasmic Reticulum Unfolded Protein Response: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. CNSNDDT 2021, 20, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarini-Gakiye, E.; Sanadgol, N.; Parivar, K.; Vaezi, G. Alpha-lipoic Acid Ameliorates Tauopathy-induced Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis, and Behavioral Deficits through the Balance of DIAP1/DrICE Ratio and Redox Homeostasis: Age Is a Determinant Factor. Metab. Brain Dis. 2021, 36, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-H.; Wang, D.-W.; Xu, S.-F.; Zhang, S.; Fan, Y.-G.; Yang, Y.-Y.; Guo, S.-Q.; Wang, S.; Guo, T.; Wang, Z.-Y.; et al. α-Lipoic Acid Improves Abnormal Behavior by Mitigation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Ferroptosis, and Tauopathy in P301S Tau Transgenic Mice. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Rosario, E.R.; Soper, J.C.; Pike, C.J. Androgens Regulate Tau Phosphorylation Through Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase–Protein Kinase B–Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β Signaling. Neuroscience 2025, 568, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggal, P.; Jadaun, K.S.; Siqqiqui, E.M.; Mehan, S. Investigation of Low Dose Cabazitaxel Potential as Microtubule Stabilizer in Experimental Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: Restoring Neuronal Cytoskeleton. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2020, 17, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.B.; Peres, K.C.; Ribeiro, R.P.; Colle, D.; dos Santos, A.A.; Moreira, E.L.G.; Souza, D.O.G.; Figueiredo, C.P.; Farina, M. Probucol, a Lipid-Lowering Drug, Prevents Cognitive and Hippocampal Synaptic Impairments Induced by Amyloid β Peptide in Mice. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 233, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-de-la-Rosa, M.; Silva, I.; Nilsen, J.; Pérez, M.M.; García-Segura, L.M.; Avila, J.; Naftolin, F. Estradiol Prevents Neural Tau Hyperphosphorylation Characteristic of Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1052, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, A.V.; Wheeler, J.M.; Guthrie, C.R.; Liachko, N.F.; Kraemer, B.C. Dopamine D2 Receptor Antagonism Suppresses Tau Aggregation and Neurotoxicity. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, J.; Sabbagh, M.N.; Kang, M.H.; Lawrence, J.J.; Pruitt, K.; Bacus, S.; Reyna, E.; Brown, M.; Decourt, B. Cancer Drugs with High Repositioning Potential for Alzheimer’s Disease. Expert. Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2023, 28, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, E.; Zhao, W.; Qian, X.; Freire, D.; Bilski, A.E.; Cheng, A.; Vempati, P.; Ho, L.; et al. Unintended Effects of Cardiovascular Drugs on the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samir, S.M.; Hassan, H.M.; Elmowafy, R.; ElNashar, E.M.; Alghamdi, M.A.; AlSheikh, M.H.; Al-Zahrani, N.S.; Alasiri, F.M.; Elhadidy, M.G. Neuroprotective Effect of Ranolazine Improves Behavioral Discrepancies in a Rat Model of Scopolamine-Induced Dementia. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1267675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, A.; Siddiqi, F.H.; Villeneuve, J.; Ureshino, R.P.; Jeon, H.-Y.; Koulousakis, P.; Keeling, S.; McEwan, W.A.; Fleming, A.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibition Ameliorates Tau Toxicity via Enhanced Tau Secretion. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2025, 21, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Chen, S.R.W. R-Carvedilol, a Potential New Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1062495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, U.; Dwivedi, H.; Subramaniam, J.R. Reserpine Ameliorates Aβ Toxicity in the Alzheimer’s Disease Model in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Exp. Gerontol. 2009, 44, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasantharaja, R.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; Subramaniam, J.R. Reserpine Improves Working Memory. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 2016, 6, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

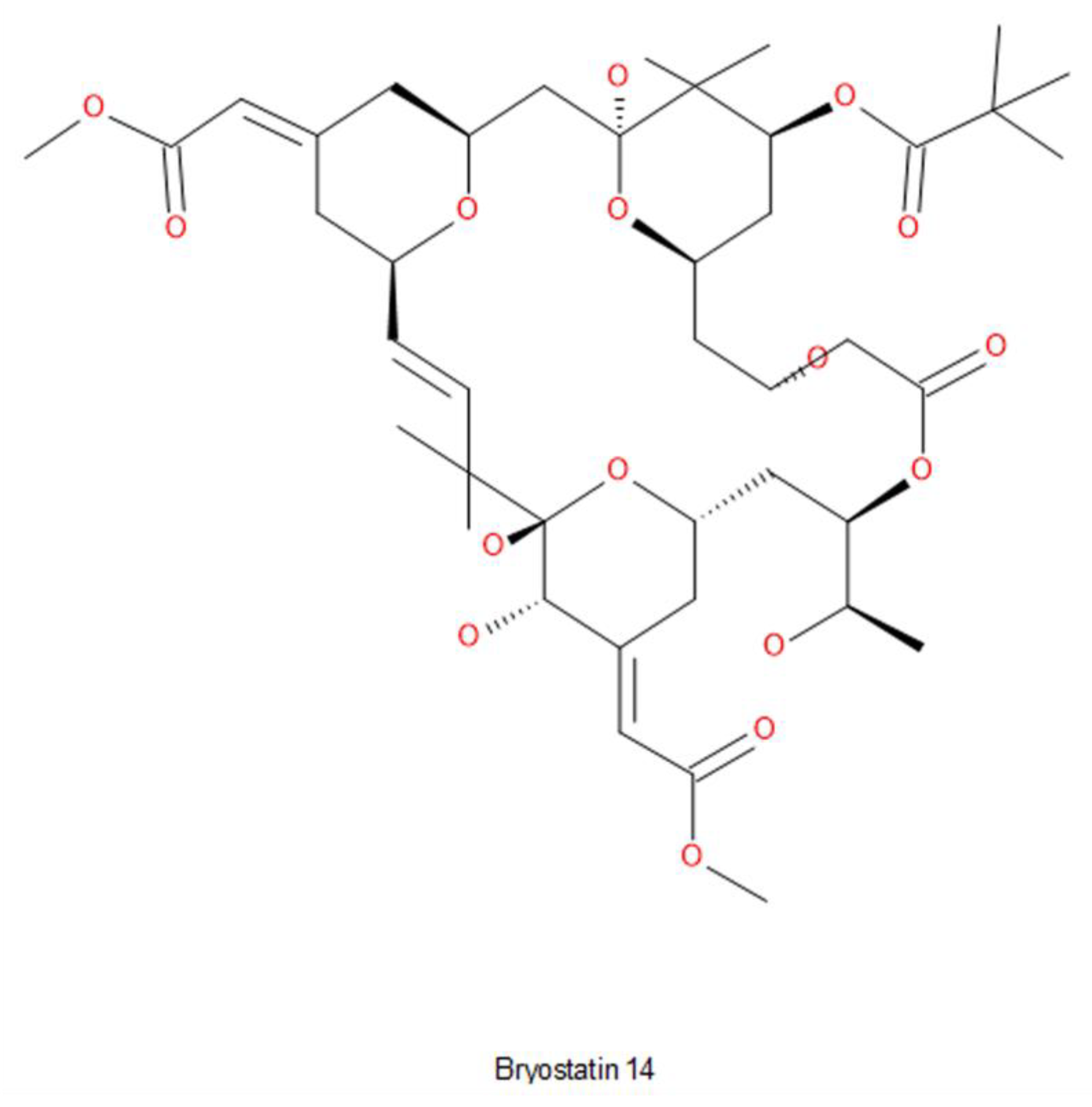

- Hongpaisan, J.; Sun, M.-K.; Alkon, D.L. PKC ε Activation Prevents Synaptic Loss, Aβ Elevation, and Cognitive Deficits in Alz-heimer’s Disease Transgenic Mice. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrott, L.M.; Jackson, K.; Yi, P.; Dietz, F.; Johnson, G.S.; Basting, T.F.; Purdum, G.; Tyler, T.; Rios, J.D.; Castor, T.P.; et al. Acute Oral Bryostatin-1 Administration Improves Learning Deficits in the APP/PS1 Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. CAR 2015, 12, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Jiang, G.; Tang, W.; Zhao, X.; Chen, F.; Zhang, X.; Ye, N. Aporphines: A Privileged Scaffold in CNS Drug Discovery. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 256, 115414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontes Barbosa, M.; Benatti Justino, A.; Machado Martins, M.; Roberta Anacleto Belaz, K.; Barbosa Ferreira, F.; Junio de Oliveira, R.; Danuello, A.; Salmen Espindola, F.; Pivatto, M. Cholinesterase Inhibitors Assessment of Aporphine Alkaloids from Annona Crassiflora and Molecular Docking Studies. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 120, 105593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabavi, S.M.; Uriarte, E.; Rastrelli, L.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E. Aporphines and Alzheimer’s Disease: Towards a Medical Approach Facing the Future. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 3253–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sichaem, J.; Tip-pyang, S.; Lugsanangarm, K. Bioactive Aporphine Alkaloids from the Roots of Artabotrys Spinosus: Cholines-terase Inhibitory Activity and Molecular Docking Studies. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 1934578X1801301011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Sun, J. Oxoisoaporphine Alkaloids: Prospective Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease, Anticancer, and Antidepressant Agents. Chem. Med. Chem. 2018, 13, 1262–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

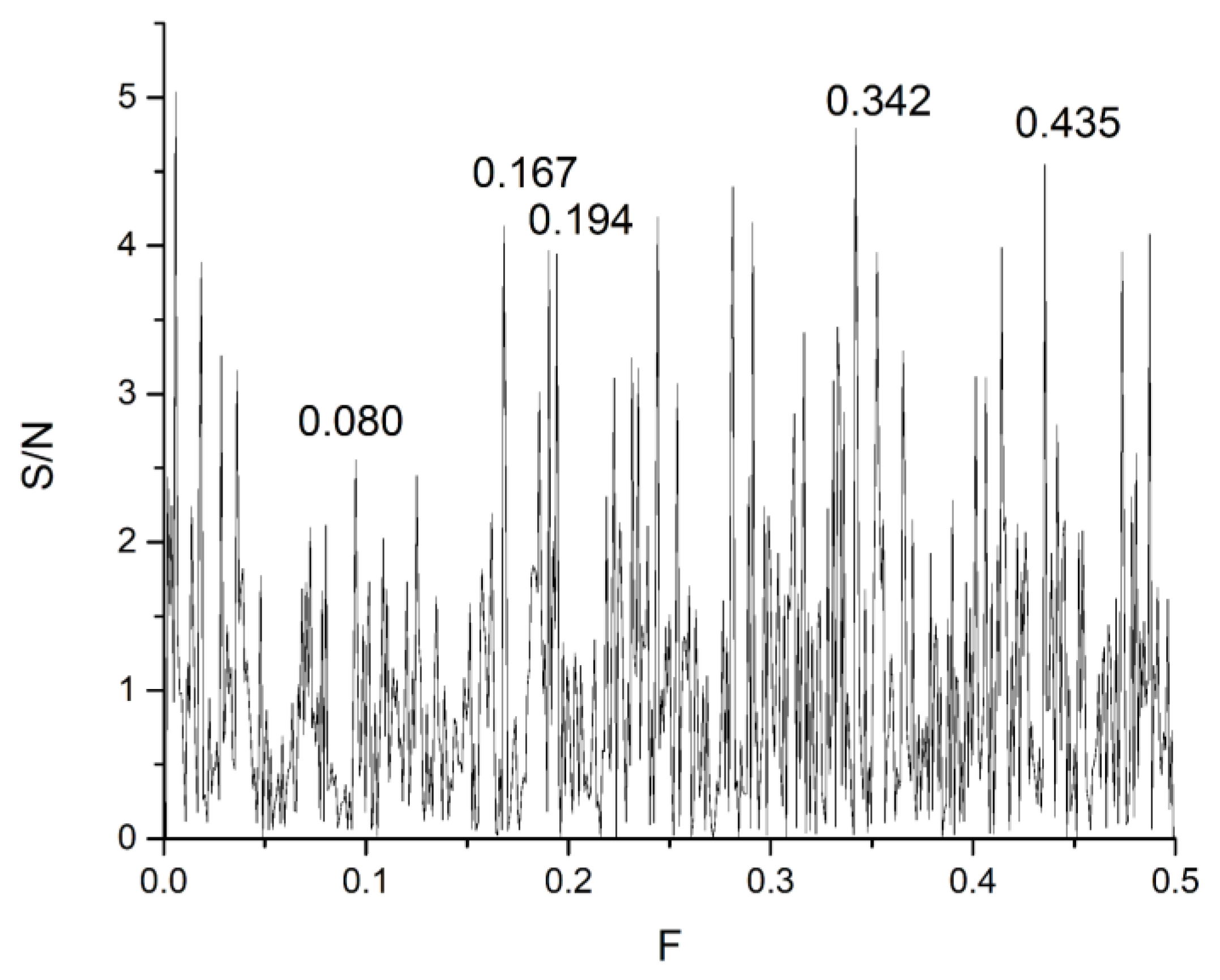

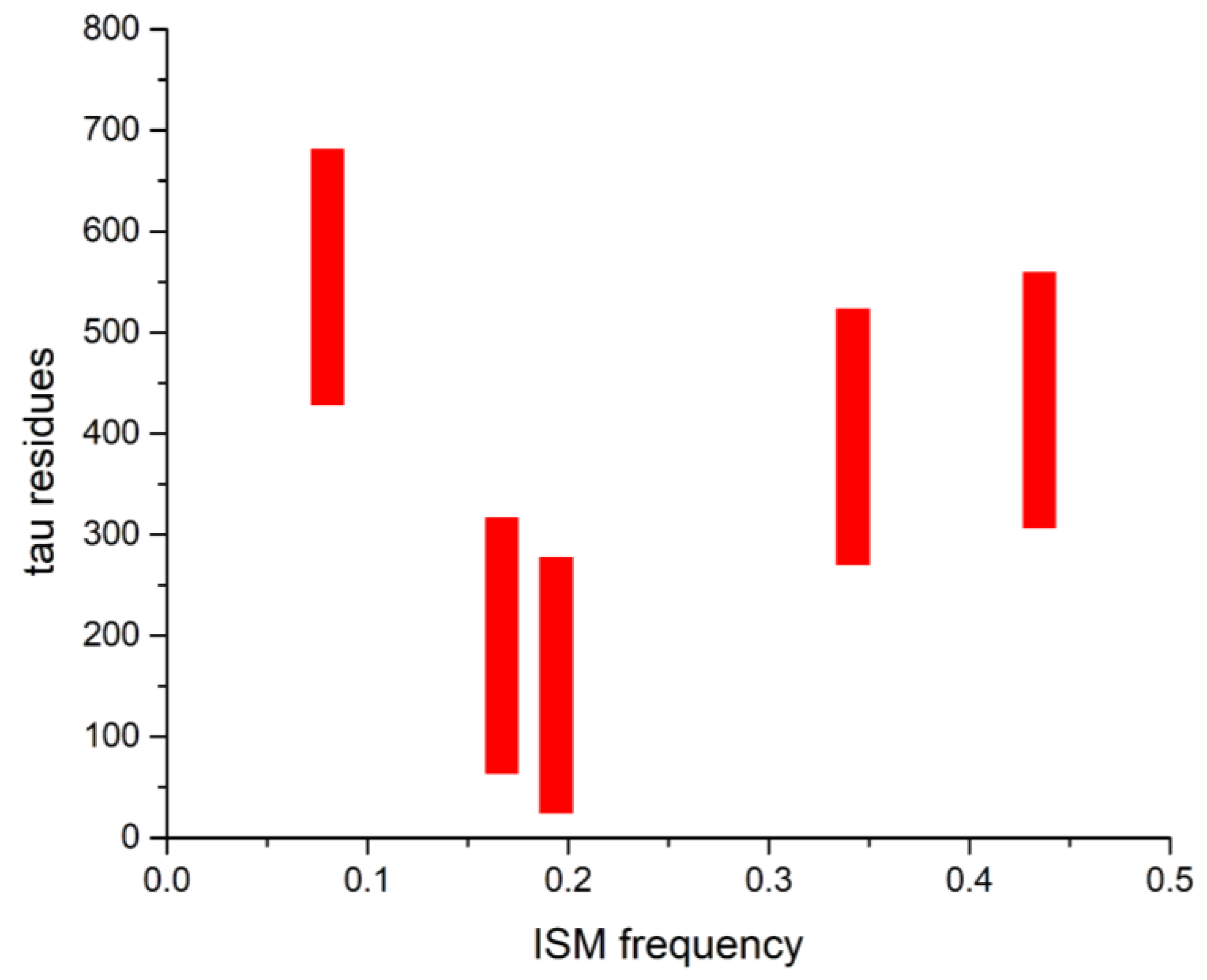

| DrugBank Compound | Name | CS with tau Frequencies | Amplitude | S/N | Corresponding Domain in the tau Protein | Literature Binding Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB00637 | Astemizole | 0.342 | 0.9958 | 17.353 | 269–525 | 386–391 |

| DB01248 | Docetaxel | 0.167 | 1.7847 | 20.023 | 62–318 | β-tubulin |

| DB14914 | Flortaucipir F-18 | 0.080 | 0.10816 | 9.0225 | 427–683 | R3–R4 386–391 |

| DB00448 | Lansoprazole | 0.435 | 0.65514 | 12.299 | 305–561 | R3–R4 386–391 |

| DB01229 | Paclitaxel | 0.194 | 1.1917 | 14.089 | 23–279 | β-tubulin |

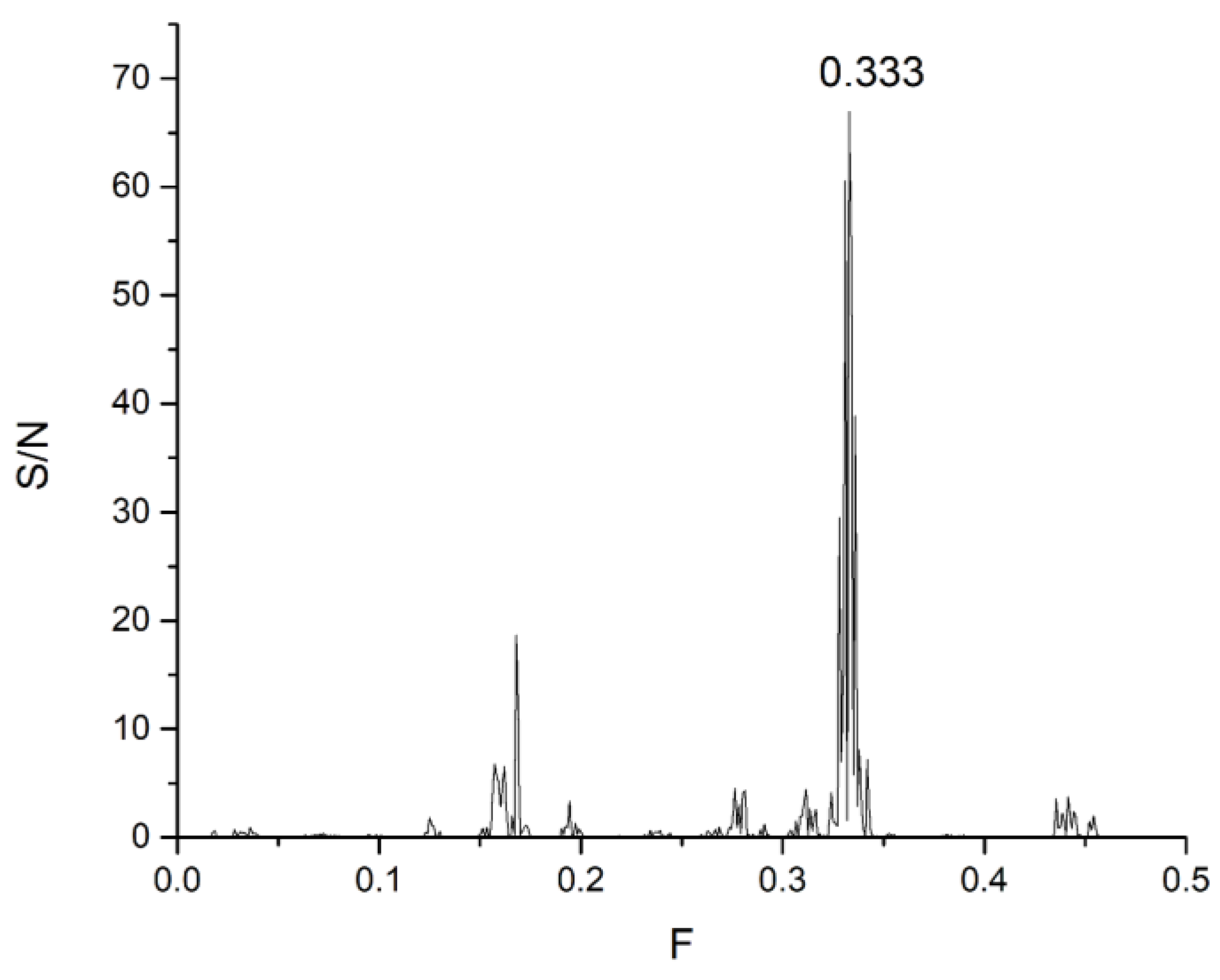

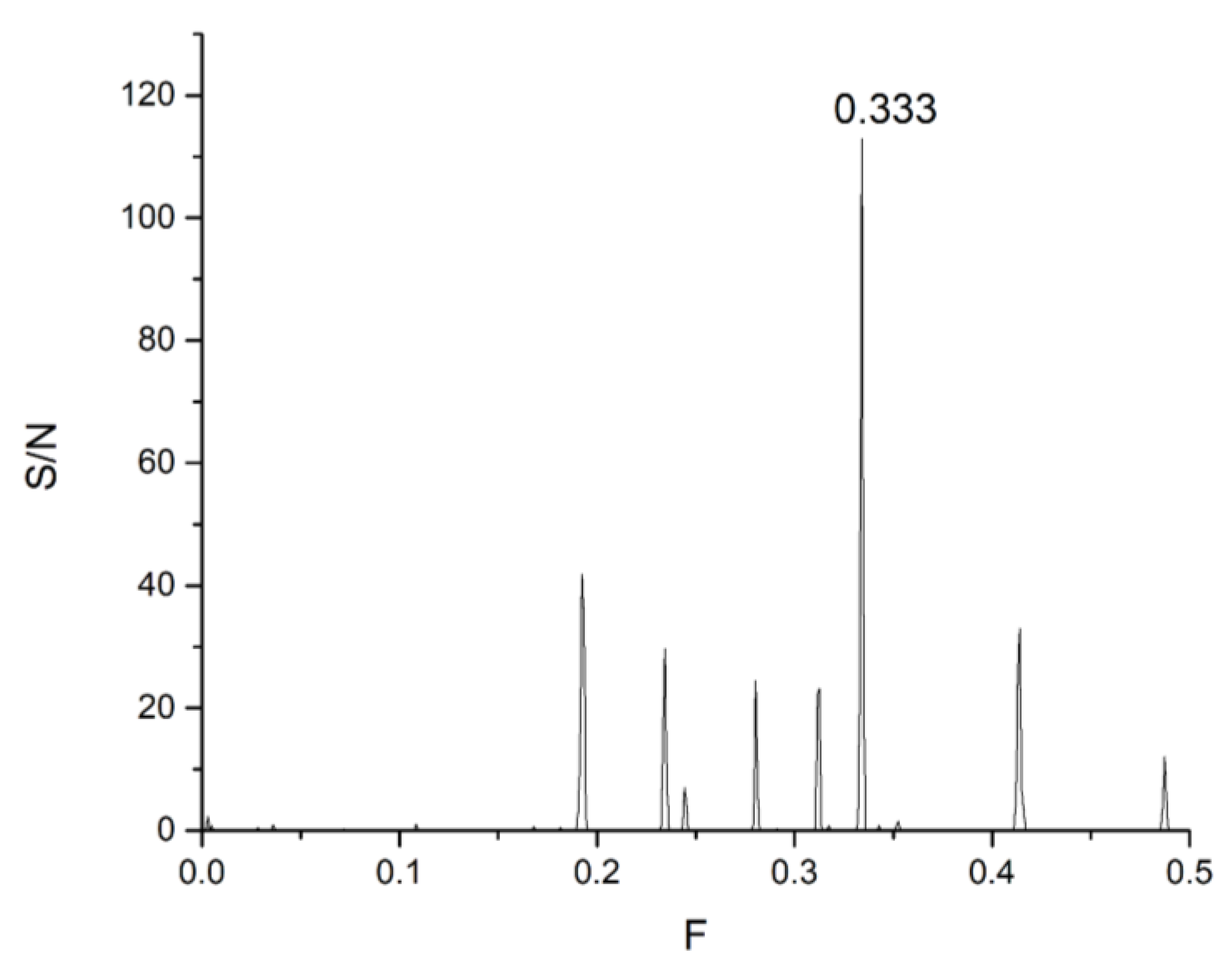

| No | ID | Name | Amplitude | S/N | Frequency | Effect on tau Protein/AD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DB01012 | Cinacalcet | 0.40481 | 13.45278 | 0.080 | Indirect on tau phosphorylation |

| 2 | DB01393 | Bezafibrate | 0.32723 | 9.6733 | 0.080 | Reduces Aβ and tau pathology |

| 3 | DB06287 | Temsirolimus | 1.14833 | 28.35191 | 0.167 | Reducing tau hyperphosphorylation |

| 4 | DB01590 | Everolimus | 3.23776 | 20.74836 | 0.167 | Reducing tau hyperphosphorylation |

| 5 | DB00035 | Desmopressin | 2.30313 | 20.55908 | 0.167 | Could influence Aβ/tau cross-interactions |

| 6 | DB01130 | Prednicarbate | 1.34609 | 18.58936 | 0.167 | Potential tau aggregation modulator |

| 7 | DB01656 | Roflumilast | 17.85085 | 0.05962 | 0.167 | Ameliorates cognitive deficits in tauopathy models |

| 8 | DB00166 | Lipoic acid | 17.1443 | 0.04087 | 0.167 | Reduces tauopathy |

| 9 | DB01420 | Testosterone Propionate | 1.00595 | 22.21979 | 0.194 | Hyperphosphorylation of tau |

| 10 | DB06772 | Cabazitaxel | 2.47515 | 22.12693 | 0.194 | Microtubule stabilization |

| 11 | DB01599 | Probucol | 0.50271 | 19.55832 | 0.194 | Reduce amyloid deposition |

| 12 | DB08866 | Estradiol valerate/Dienogest | 0.91072 | 19.02854 | 0.194 | Prevents tau hyperphosphorylation |

| 13 | DB00850 | Perphenazine | 0.71948 | 14.65717 | 0.333 | Lower the levels of insoluble tau. |

| 14 | DB06699 | Degarelix | 2.05541 | 13.78509 | 0.333 | Hormone modulation may influence neurodegeneration |

| 15 | DB00883 | Isosorbide Dinitrate | 0.87453 | 22.00889 | 0.342 | Nitric oxide modulation (could influence neurodegeneration) |

| 16 | DB00243 | Ranolazine | 1.48002 | 23.2534 | 0.435 | Reduces oxidative stress, lacks tau-specific evidence |

| 17 | DB00423 | Methocarbamol | 0.80441 | 21.58701 | 0.435 | Promoting tau clearance |

| 18 | DB01136 | Carvedilol | 1.07707 | 21.14359 | 0.435 | May reduce Aβ and tau toxicity |

| 19 | DB00206 | Reserpine | 2.15401 | 19.96937 | 0.435 | Reduces Aβ toxicity |

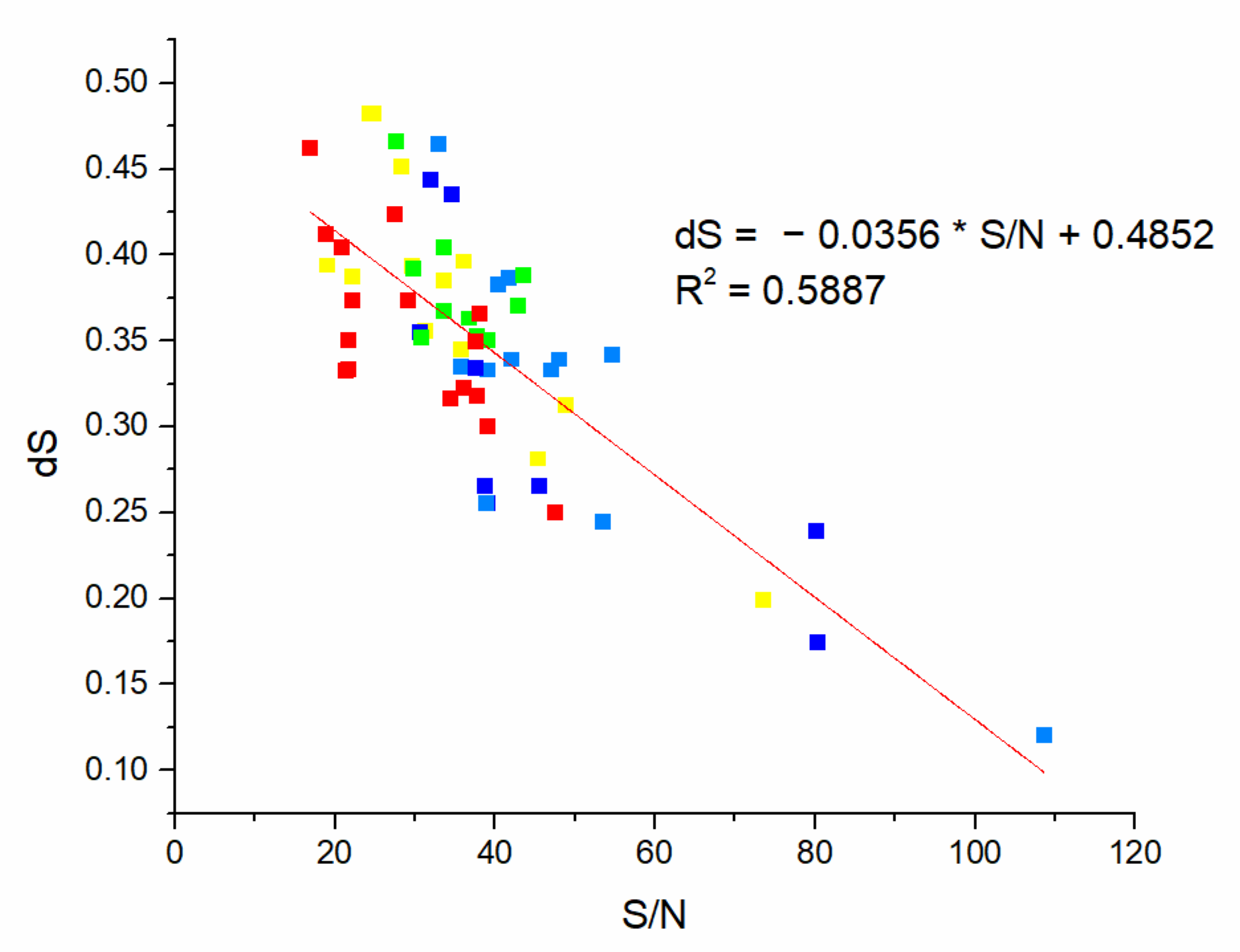

| Compound ID | Amplitude | S/N | Drug Score | Total Score | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNP0504067.0 | 2.6931 | 27.5146 | 0.4236 | 11.6548 | 0.080 |

| CNP0126636.1 | 2.0462 | 22.2079 | 0.3871 | 8.5975 | |

| CNP0560502.0 | 0.9447 | 20.8465 | 0.4040 | 8.4210 | |

| CNP0195295.1 | 1.7374 | 22.2690 | 0.3734 | 8.3160 | |

| CNP0532732.0 | 0.5916 | 16.8757 | 0.4619 | 7.7952 | |

| CNP0581434.0 | 0.9140 | 18.8845 | 0.4116 | 7.7720 | |

| CNP0111317.1 | 1.0835 | 21.7010 | 0.3503 | 7.6024 | |

| CNP0154283.1 | 1.7748 | 19.1053 | 0.3937 | 7.5220 | |

| CNP0285595.1 | 0.9112 | 21.7744 | 0.3330 | 7.2507 | |

| CNP0511033.0 | 0.7804 | 21.4297 | 0.3323 | 7.1204 | |

| CNP0266316.1 | 4.2790 | 33.7220 | 0.3849 | 12.9806 | 0.167 |

| CNP0168057.1 | 4.9895 | 35.8560 | 0.3450 | 12.3714 | |

| CNP0427543.1 | 3.5080 | 37.8452 | 0.3181 | 12.0369 | |

| CNP0135438.1 | 3.0234 | 39.1900 | 0.3002 | 11.7653 | |

| CNP0327834.1 | 2.5014 | 36.2093 | 0.3224 | 11.6753 | |

| CNP0297394.1 | 3.1593 | 31.3039 | 0.3558 | 11.1366 | |

| CNP0359990.1 | 3.0488 | 34.4367 | 0.3164 | 10.8969 | |

| CNP0449680.1 | 6.3795 | 30.7200 | 0.3544 | 10.8859 | |

| CNP0072358.1 | 1.5625 | 29.1654 | 0.3732 | 10.8849 | |

| CNP0280000.1 | 4.7052 | 30.8741 | 0.3516 | 10.8550 | |

| CNP0267855.1 | 7.1527 | 54.7695 | 0.3416 | 18.7103 | 0.194 |

| CNP0115161.1 | 5.9639 | 48.0360 | 0.3389 | 16.2787 | |

| CNP0271940.1 | 6.0078 | 47.1667 | 0.3328 | 15.6975 | |

| CNP0144759.1 | 3.8288 | 32.9508 | 0.4640 | 15.2877 | |

| CNP0399889.1 | 5.2859 | 42.0429 | 0.3389 | 14.2478 | |

| CNP0271195.1 | 5.0978 | 39.0668 | 0.3328 | 13.0018 | |

| CNP0206347.1 | 5.2161 | 27.6665 | 0.4660 | 12.8917 | |

| CNP0075233.1 | 4.1613 | 35.8159 | 0.3348 | 11.9926 | |

| CNP0199404.1 | 2.0896 | 47.5628 | 0.2497 | 11.8770 | |

| CNP0337940.1 | 3.9174 | 29.6884 | 0.3930 | 11.6670 | |

| CNP0425508.1 | 8.0539 | 41.7191 | 0.3861 | 16.1071 | 0.333 |

| CNP0426456.1 | 7.3556 | 40.4095 | 0.3824 | 15.4512 | |

| CNP0580557.0 | 79.8827 | 108.7010 | 0.1205 | 13.0938 | |

| CNP0492610.1 | 6.6601 | 45.5939 | 0.2655 | 12.1062 | |

| CNP0574550.1 | 4.4607 | 24.8369 | 0.4820 | 11.9716 | |

| CNP0493035.1 | 4.3748 | 24.4605 | 0.4820 | 11.7901 | |

| CNP0598400.0 | 5.2834 | 29.8102 | 0.3916 | 11.6749 | |

| CNP0571478.1 | 5.5340 | 38.7741 | 0.2655 | 10.2954 | |

| CNP0491847.1 | 5.6254 | 39.1878 | 0.2556 | 10.0162 | |

| CNP0357360.0 | 7.9691 | 39.0120 | 0.2556 | 9.9713 | |

| CNP0285895.1 | 8.6899 | 43.5842 | 0.3877 | 16.8988 | 0.341 |

| CNP0313376.1 | 8.3450 | 42.9529 | 0.3704 | 15.9113 | |

| CNP0578185.1 | 6.3962 | 32.0514 | 0.4437 | 14.2199 | |

| CNP0291861.1 | 6.2579 | 39.1064 | 0.3501 | 13.6928 | |

| CNP0538593.1 | 3.9683 | 33.6090 | 0.4039 | 13.5734 | |

| CNP0180487.0 | 5.7451 | 36.7896 | 0.3628 | 13.3468 | |

| CNP0525297.1 | 6.1290 | 37.8186 | 0.3521 | 13.3144 | |

| CNP0423521.1 | 5.3032 | 45.4780 | 0.2811 | 12.7837 | |

| CNP0549106.1 | 7.1238 | 37.6706 | 0.3341 | 12.5872 | |

| CNP0319138.1 | 4.8550 | 33.6416 | 0.3671 | 12.3481 | |

| CNP0551487.1 | 16.0579 | 80.2087 | 0.2389 | 19.1640 | 0.435 |

| CNP0199424.0 | 6.8985 | 48.9195 | 0.3121 | 15.2669 | |

| CNP0509389.2 | 3.9253 | 34.6086 | 0.4348 | 15.0463 | |

| CNP0105199.1 | 15.3904 | 73.5380 | 0.1991 | 14.6407 | |

| CNP0417346.0 | 4.4444 | 36.2080 | 0.3960 | 14.3374 | |

| CNP0048849.1 | 26.4727 | 80.3243 | 0.1742 | 13.9922 | |

| CNP0061932.1 | 2.4242 | 38.1590 | 0.3657 | 13.9535 | |

| CNP0151916.0 | 2.4107 | 37.6099 | 0.3492 | 13.1339 | |

| CNP0078724.1 | 20.8988 | 53.4832 | 0.2448 | 13.0907 | |

| CNP0429159.1 | 1.9277 | 28.3867 | 0.4510 | 12.8016 |

| Compound ID | S/N | Drug Score | Distance to Cluster | F | Total Score 2 (S/N/Distance to Centroid) | Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNP0151916.0 | 37.6099 | 0.3492 | 23.1768 | 0.435 | 1.6227 | 1 |

| CNP0327834.1 | 36.2093 | 0.3224 | 53.6144 | 0.167 | 0.6754 | |

| CNP0072358.1 | 29.1654 | 0.3732 | 44.1454 | 0.167 | 0.6607 | |

| CNP0504067.0 | 27.5146 | 0.4236 | 54.1343 | 0.08 | 0.5083 | |

| CNP0199404.1 | 47.5628 | 0.2497 | 110.9528 | 0.194 | 0.4287 | |

| CNP0061932.1 | 38.1590 | 0.3657 | 101.6911 | 0.435 | 0.3752 | |

| CNP0427543.1 | 37.8452 | 0.3181 | 103.7778 | 0.167 | 0.3647 | |

| CNP0135438.1 | 39.1900 | 0.3002 | 132.4314 | 0.167 | 0.2959 | |

| CNP0511033.0 | 21.4297 | 0.3323 | 75.7621 | 0.08 | 0.2829 | |

| CNP0560502.0 | 20.8465 | 0.4040 | 79.2396 | 0.08 | 0.2631 | |

| CNP0111317.1 | 21.7010 | 0.3503 | 97.8961 | 0.08 | 0.2217 | |

| CNP0359990.1 | 34.4367 | 0.3164 | 164.0605 | 0.167 | 0.2099 | |

| CNP0581434.0 | 18.8845 | 0.4116 | 94.3867 | 0.08 | 0.2001 | |

| CNP0285595.1 | 21.7744 | 0.3330 | 110.4145 | 0.08 | 0.1972 | |

| CNP0532732.0 | 16.8757 | 0.4619 | 105.8951 | 0.08 | 0.1594 | |

| CNP0195295.1 | 22.2690 | 0.3734 | 173.7049 | 0.08 | 0.1282 | |

| CNP0337940.1 | 29.6884 | 0.3930 | 15.2877 | 0.194 | 1.9420 | 2 |

| CNP0199424.0 | 48.9195 | 0.3121 | 44.9265 | 0.435 | 1.0889 | |

| CNP0574550.1 | 24.8369 | 0.4820 | 26.6104 | 0.333 | 0.9334 | |

| CNP0493035.1 | 24.4605 | 0.4820 | 26.3254 | 0.333 | 0.9292 | |

| CNP0266316.1 | 33.7220 | 0.3849 | 44.7305 | 0.167 | 0.7539 | |

| CNP0126636.1 | 22.2079 | 0.3871 | 35.9000 | 0.08 | 0.6186 | |

| CNP0105199.1 | 73.5380 | 0.1991 | 140.4245 | 0.435 | 0.5237 | |

| CNP0168057.1 | 35.8560 | 0.3450 | 78.0769 | 0.167 | 0.4592 | |

| CNP0429159.1 | 28.3867 | 0.4510 | 64.1686 | 0.435 | 0.4424 | |

| CNP0154283.1 | 19.1053 | 0.3937 | 46.2699 | 0.08 | 0.4129 | |

| CNP0423521.1 | 45.4780 | 0.2811 | 115.1818 | 0.341 | 0.3948 | |

| CNP0417346.0 | 36.2080 | 0.3960 | 107.3436 | 0.435 | 0.3373 | |

| CNP0297394.1 | 31.3039 | 0.3558 | 95.0548 | 0.167 | 0.3293 | |

| CNP0180487.0 | 36.7896 | 0.3628 | 13.9520 | 0.341 | 2.6369 | 3 |

| CNP0313376.1 | 42.9529 | 0.3704 | 20.4250 | 0.341 | 2.1030 | |

| CNP0525297.1 | 37.8186 | 0.3521 | 34.1682 | 0.341 | 1.1068 | |

| CNP0319138.1 | 33.6416 | 0.3671 | 44.9490 | 0.341 | 0.7484 | |

| CNP0291861.1 | 39.1064 | 0.3501 | 66.2943 | 0.341 | 0.5899 | |

| CNP0285895.1 | 43.5842 | 0.3877 | 79.0845 | 0.341 | 0.5511 | |

| CNP0598400.0 | 29.8102 | 0.3916 | 57.8419 | 0.333 | 0.5154 | |

| CNP0280000.1 | 30.8741 | 0.3516 | 77.4212 | 0.167 | 0.3988 | |

| CNP0538593.1 | 33.6090 | 0.4039 | 99.8643 | 0.341 | 0.3365 | |

| CNP0206347.1 | 27.6665 | 0.4660 | 87.9175 | 0.194 | 0.3147 | |

| CNP0115161.1 | 48.0360 | 0.3389 | 64.0638 | 0.194 | 0.7498 | 4 |

| CNP0271940.1 | 47.1667 | 0.3328 | 63.0634 | 0.194 | 0.7479 | |

| CNP0399889.1 | 42.0429 | 0.3389 | 64.2465 | 0.194 | 0.6544 | |

| CNP0271195.1 | 39.0668 | 0.3328 | 62.7261 | 0.194 | 0.6228 | |

| CNP0267855.1 | 54.7695 | 0.3416 | 112.7427 | 0.194 | 0.4858 | |

| CNP0075233.1 | 35.8159 | 0.3348 | 78.4168 | 0.194 | 0.4567 | |

| CNP0580557.0 | 108.7010 | 0.1205 | 266.9120 | 0.333 | 0.4073 | |

| CNP0426456.1 | 40.4095 | 0.3824 | 151.0078 | 0.333 | 0.2676 | |

| CNP0425508.1 | 41.7191 | 0.3861 | 166.1188 | 0.333 | 0.2511 | |

| CNP0357360.0 | 39.0120 | 0.2556 | 163.7966 | 0.333 | 0.2382 | |

| CNP0078724.1 | 53.4832 | 0.2448 | 356.3395 | 0.435 | 0.1501 | |

| CNP0144759.1 | 32.9508 | 0.4640 | 224.4241 | 0.194 | 0.1468 | |

| CNP0551487.1 | 80.2087 | 0.2389 | 134.2948 | 0.435 | 0.5973 | 5 |

| CNP0048849.1 | 80.3243 | 0.1742 | 137.0805 | 0.435 | 0.5860 | |

| CNP0509389.2 | 34.6086 | 0.4348 | 79.4140 | 0.435 | 0.4358 | |

| CNP0492610.1 | 45.5939 | 0.2655 | 121.3631 | 0.333 | 0.3757 | |

| CNP0491847.1 | 39.1878 | 0.2556 | 106.6358 | 0.333 | 0.3675 | |

| CNP0549106.1 | 37.6706 | 0.3341 | 108.1871 | 0.341 | 0.3482 | |

| CNP0578185.1 | 32.0514 | 0.4437 | 95.4639 | 0.341 | 0.3357 | |

| CNP0571478.1 | 38.7741 | 0.2655 | 121.3645 | 0.333 | 0.3195 | |

| CNP0449680.1 | 30.7200 | 0.3544 | 102.7158 | 0.167 | 0.2991 |

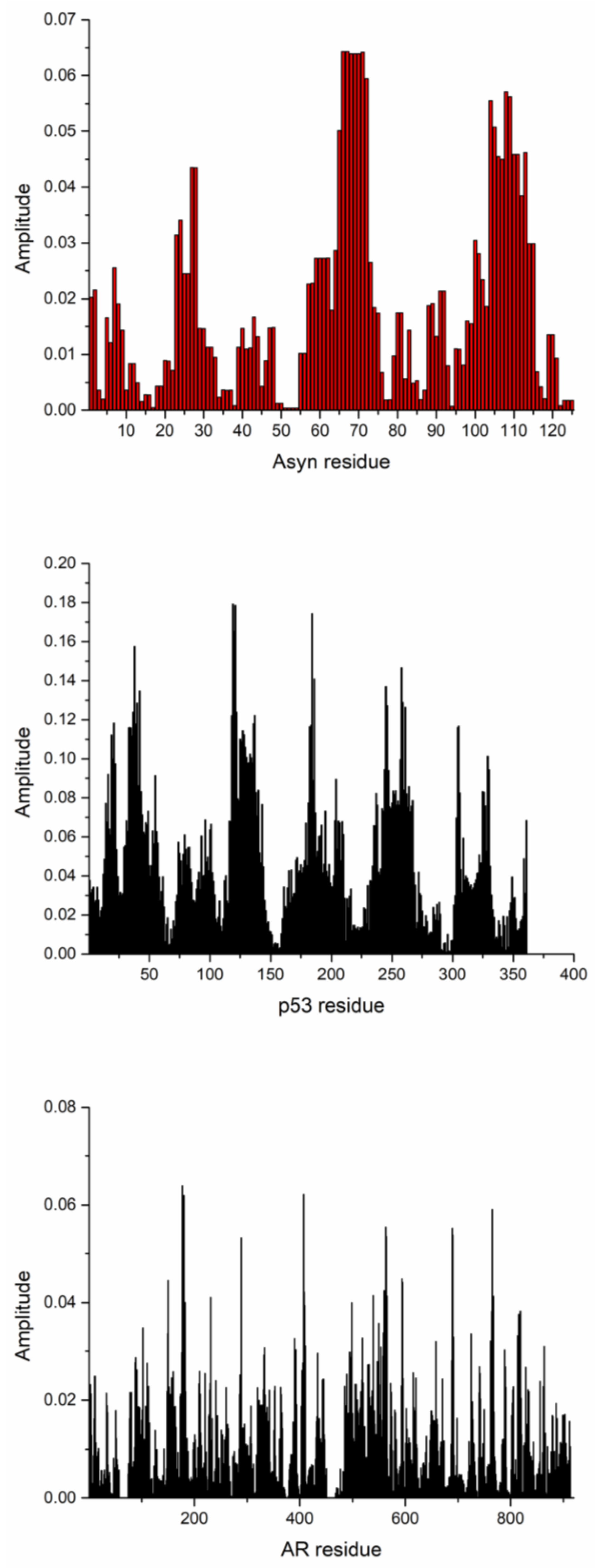

| System | Martini-IDP | ISM-SM Region |

|---|---|---|

| alpha-synuclein- fasudil | 3, 38, 93, 115, 124, 127, 135 | 1, 2, 7, 23, 24, 27, 28, 66, 67, 68, 69,70, 71, 104, 108, 109 (Slide window width 17) |

| p53—Ligand 1050 | 23 | 21, 38, 119, 184, 258, 305, 329, 361 (Slide window width 33) |

| AR—EPI-002 | 396, 405, 406, 432, 433, 437, 438 | 177, 289, 407, 563, 689, 765 (Slide window width 8) |

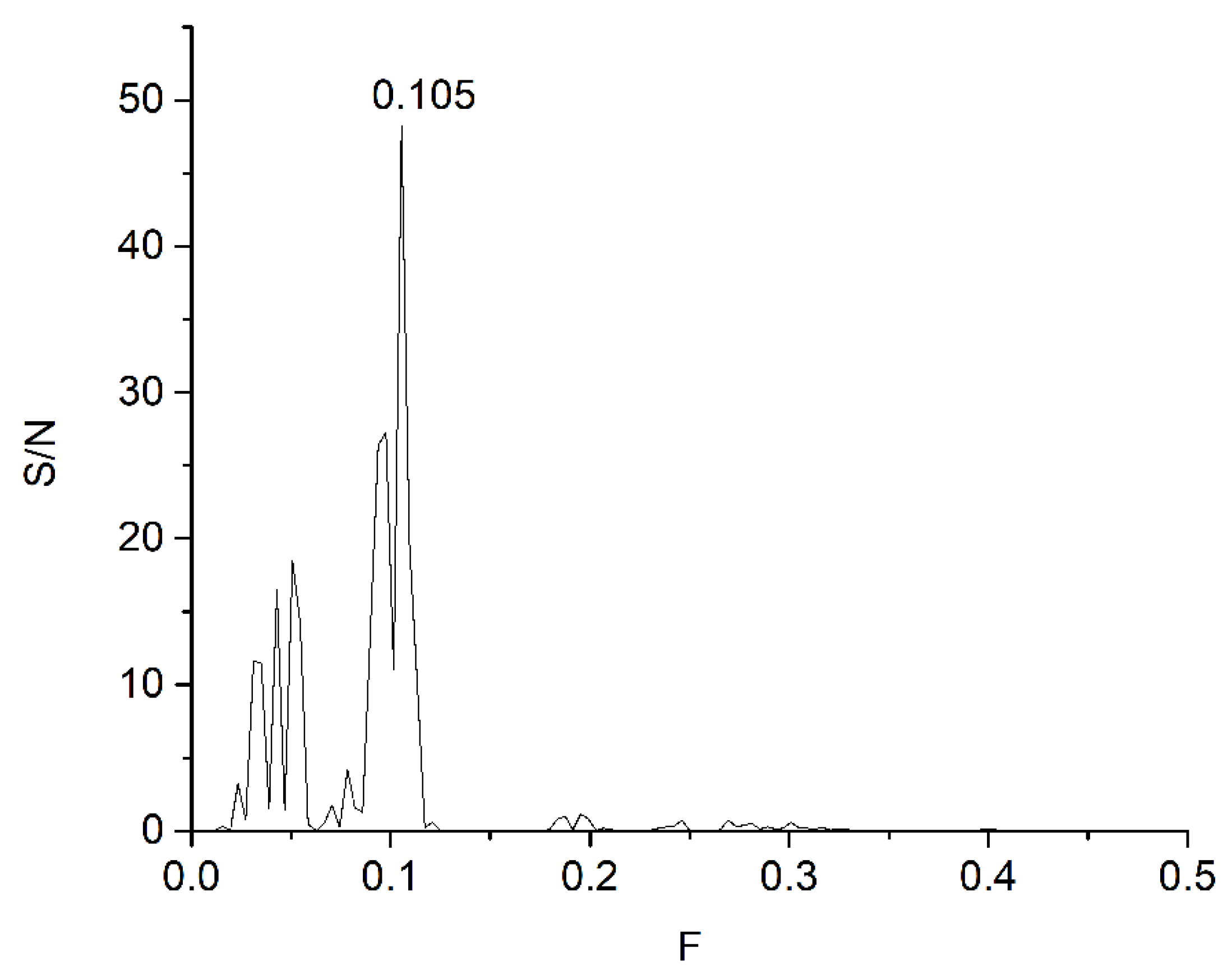

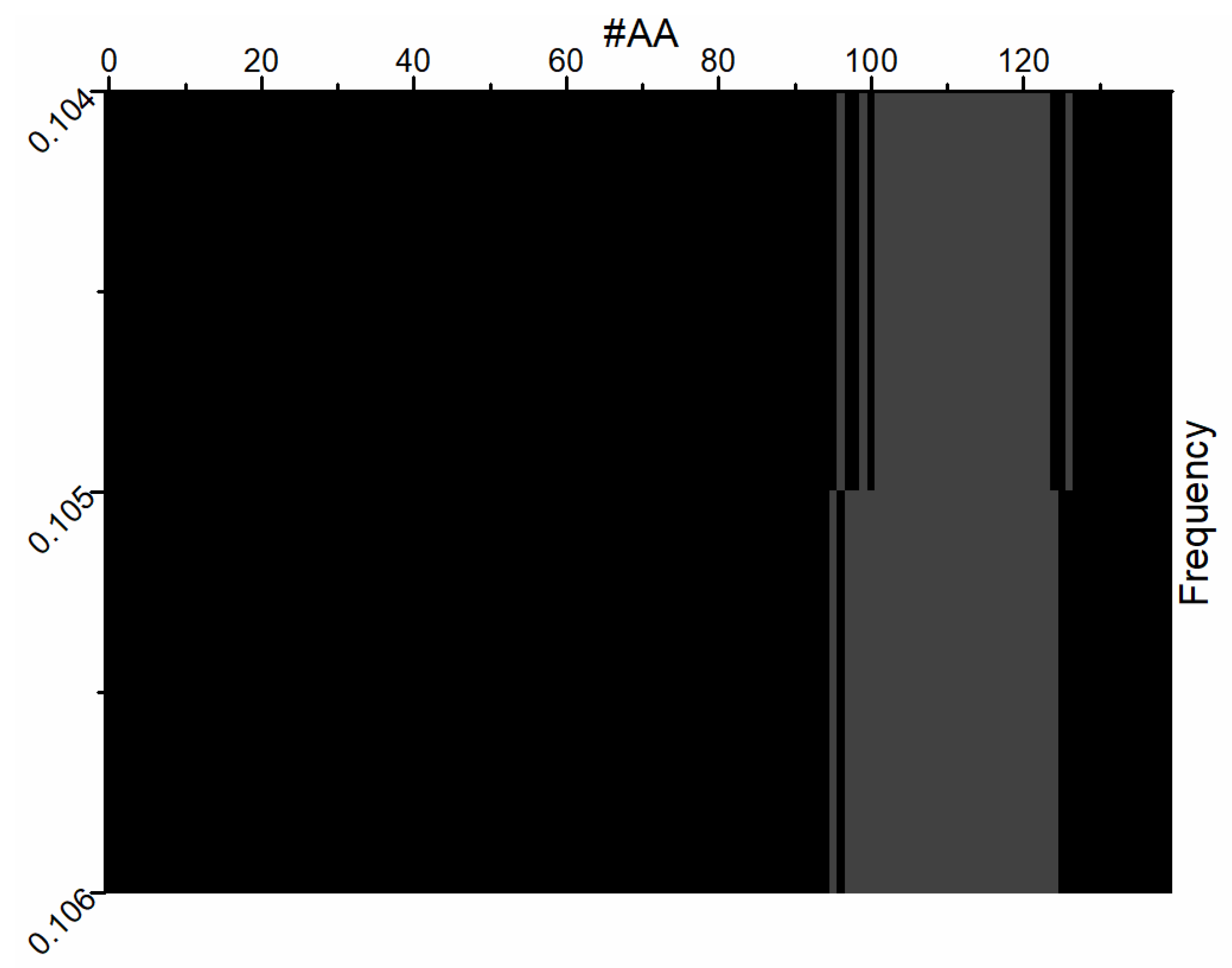

| Protein–Ligand Complex | Peak | F | A | S/N | ISM-SM Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand47 | 1 | 0.054 | 0.0772 | 11.18 | 42–106 |

| 2 | 0.105 | 0.0615 | 8.9147 | 4–132 | |

| 3 | 0.226 | 0.0438 | 6.3474 | 70–134 | |

| Fasudil | 1 | 0.105 | 0.0972 | 12.359 | 4–132 |

| 2 | 0.031 | 0.0720 | 9.1587 | 57–121 | |

| 3 | 0.093 | 0.0667 | 8.4796 | 7–71 | |

| Ligand23 | 1 | 0.300 | 0.0342 | 7.4993 | 57–121 |

| 2 | 0.351 | 0.0298 | 6.5445 | 71–135 | |

| 3 | 0.105 | 0.0287 | 6.2984 | 4–132 | |

| All three ligands | 1 | 0.105 | 0.0003 | 48.2984 | 4–132 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Senćanski, M. New Approach for Targeting Small-Molecule Candidates for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060150

Senćanski M. New Approach for Targeting Small-Molecule Candidates for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Methods and Protocols. 2025; 8(6):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060150

Chicago/Turabian StyleSenćanski, Milan. 2025. "New Approach for Targeting Small-Molecule Candidates for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins" Methods and Protocols 8, no. 6: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060150

APA StyleSenćanski, M. (2025). New Approach for Targeting Small-Molecule Candidates for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Methods and Protocols, 8(6), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060150