Optimized Whole-Mount Fluorescence Staining Protocol for Pulmonary Toxicity Evaluation Using Mouse Respiratory Epithelia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Design

2.1. Materials

2.2. Equipment

- Dissection Microscope with light source. Allowing up to ~8–10× magnification, e.g., Leica EZ4 (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany); Zeiss Stemi 305 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany); Olympus SZX7 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan); Nikon SMZ800N (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

- Rocking Plate, e.g., BenchRocker variable 2D rocker (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

- Fluorescent Microscope [20]: Upright or inverted; high magnification/NA (≥40×/>1 NA) water/glycerol or oil immersion objective; capable of epifluorescence or confocal fluorescence imaging. Required fluorescence filters: BLUE (Ex 405 nm/Em 451 nm), FITC (Ex 492 nm/Em 520 nm), TRITC (Ex 540–545 nm/Em 570–573 nm), e.g., Zeiss LSM 710 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

3. Procedure

3.1. Collection of Mouse Tracheas

- Euthanize the mouse using CO2 euthanasia.

- Use blunt forceps and dissecting scissors to isolate and remove the mouse pluck (heart/lungs/trachea) from the animal.

- Place the mouse pluck into a 35 mm culture dish filled with 4°C PBS onto the stage of a dissection microscope.

- Use micro scissors and tweezers to separate the trachea from the heart, lungs, esophagus, and all fat/miscellaneous tissue from the trachea surface.

- Use a P1000 pipette and P1000 tip to gently flush the tracheal lumen with PBS to remove any blood/mucus.

- Use micro-scissors to cut the trachea into short lengths (>4–5 cartilaginous rings in length), then, using two sagittal cuts, divide the trachea lengths into half trachea sections.

3.2. Trachea Treatment and Fluorescent Staining

CRITICAL STEP: Care should be taken that trachea samples are not floating on top of the liquid when washing/staining and should be completely submerged.

3.2.1. Sample Treatment

- Trachea sections are placed into 12-well plates; multiple sections can be placed per well. Recommended one well per experimental treatment containing ~5–6 trachea sections (from 5 to 6 animals), the first well is reserved for sham/control-treated samples. As 4+ trachea sections can be harvested per mouse trachea, each animal can provide a control sample and 3+ different possible sample treatments (e.g., different chemical concentrations).

- OPTIONAL STEP: Instead of using a standard 12-well plate, 12-well plates with mesh-bottomed inserts can be used (e.g., Corning NETWELL plates). This will allow easier tissue processing by simply moving inserts/tissue between wells for washing/staining.

- Trachea samples are then exposed to the treatment being assessed for toxicity (e.g., 10 min of incubation with varying concentrations of H2O2 [9]).

3.2.2. Live/Dead Staining

- Wash samples three times with PBS (1–2 mL per well/per wash).

- Dissolve the live/dead dye in DMSO as per kit instructions (50 μL of DMSO added to one vial of dye, mixed well, and visually inspect to confirm all dye has dissolved).

- Add 1 μL of the reconstituted fluorescent dye to 1 mL of PBS, mix, then add to each sample well (1 mL dye/PBS per well);

CRITICAL STEP: After the addition of fluorescent dye, samples should be protected from light for all subsequent steps. This can be performed by wrapping the 12-well plate in aluminum foil during incubations.

- Incubate samples with fluorescent dye at room temperature for 30 min.

- Wash samples once in PBS (1–2 mL per well).

- Fix samples in 4% PFA at room temperature for 15 min.

- Wash samples three times in PBS (1–2 mL per well/per wash).

PAUSE STEP: Fixed live/dead stained trachea sections can be stored at 4°C in PBS for 1–2 days before subsequent immunohistochemical staining.

3.2.3. Immunohistochemical Staining

- If previously stored at 4°C, allow samples to warm to room temperature.

- Wash samples twice in PBSFS (1–2 mL per well/per wash).

- Incubate samples in PBST (1–2 mL per well/per wash) for 10 min at room temperature.

- Block samples in PBSGS (1–2 mL per well/per wash) for 1 h at room temperature.

- Wash samples twice in ADB (1–2 mL per well/per wash).

- Incubate samples with a mouse anti-acetylated tubulin antibody diluted in ADB (1:750 dilution), 1 mL ADB/antibody per well, for 2 h at room temperature.

- Wash samples three times with PBSGS (1–2 mL per well/per wash).

- Incubate samples with a FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody in ADB (1:200 dilution) containing TRITC labelled phalloidin (1 μL/mL), 1 mL of ADB/antibody/phalloidin per well, for 1 h at room temperature.

- Wash samples once in PBSGS (1–2 mL per well/per wash).

- Wash samples three times in PBS (1–2 mL per well/per wash).

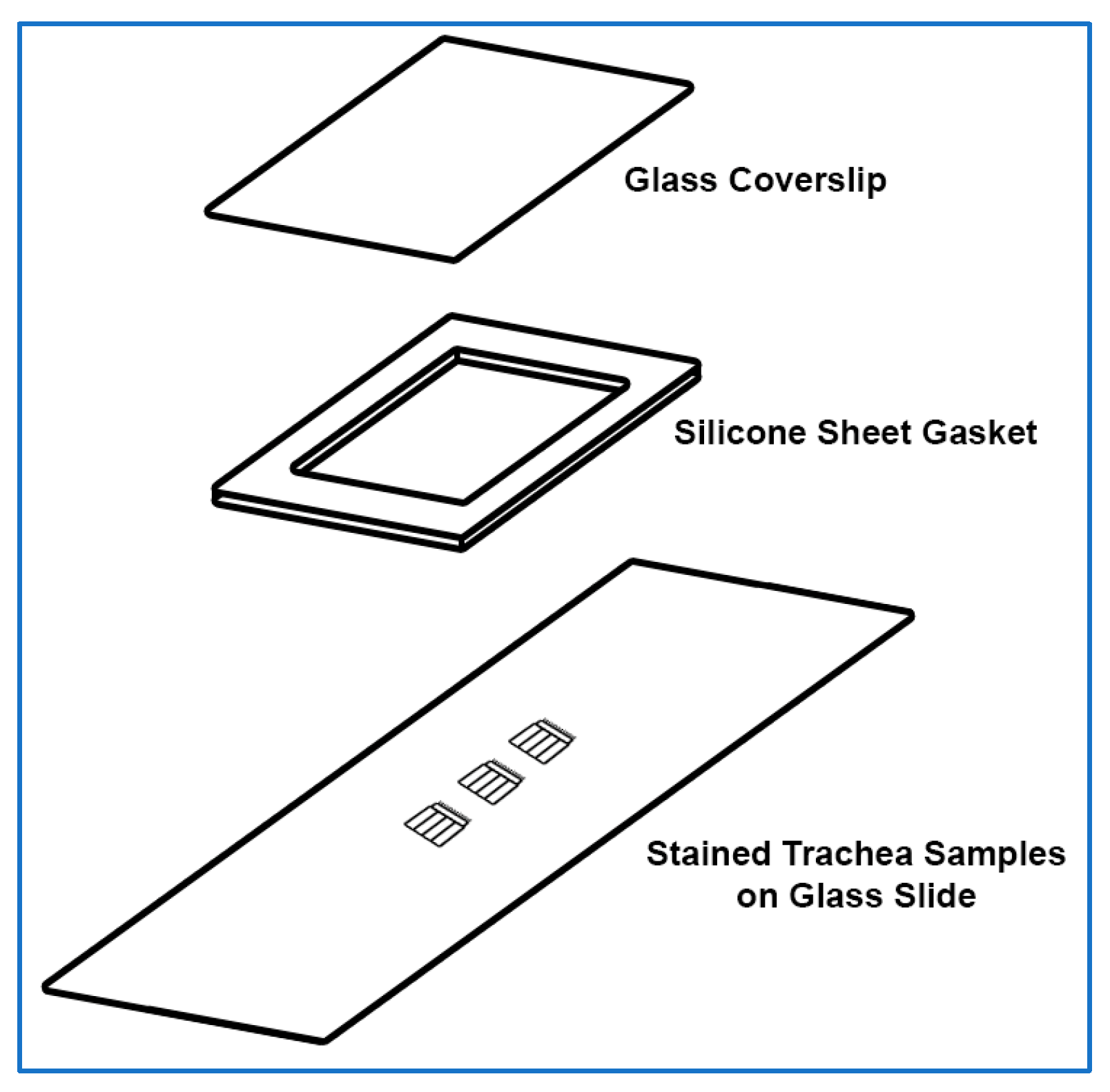

3.2.4. Sample Mounting for Imaging

- Cover a rectangular glass coverslip (24 mm × 50 mm) with ~0.127 mm thick silicone sheet; no adhesive is required, press adhesion is sufficient.

CRITICAL STEP: If the silicon sheet is powder-coated, the silicone should be thoroughly cleaned using cold water, then dried with paper towels before being used to cover a glass coverslip.

CRITICAL STEP: If the silicon sheet is powder-coated, the silicone should be thoroughly cleaned using cold water, then dried with paper towels before being used to cover a glass coverslip.- 2.

- Create a silicon gasket by cutting and removing a small rectangular section of silicone from the middle of the silicone covering the coverslip using a sharp scalpel, also, trim excess silicone from the edges of the coverslip as needed.

- 3.

- Place a glass slide (75 × 25 mm) onto the stage of a dissection microscope.

- 4.

- Using tweezers, place the trachea samples in the middle of the glass slide. Multiple samples can be placed onto the same slide (~5–6 samples per slide).

CRITICAL STEP: The trachea samples need to be placed lumen side up on the glass slide. This can be determined by observing trachea curvature under the dissection microscope.

CRITICAL STEP: The trachea samples need to be placed lumen side up on the glass slide. This can be determined by observing trachea curvature under the dissection microscope.- 5.

- Use the edge of a Kimwipe to carefully remove excess liquid from the trachea samples on the glass slide.

- 6.

- Add a drop of mountant onto the top of each trachea sample (e.g., SlowFade Diamond Antifade Mountant).

CRITICAL STEP: Care should be taken that no air bubbles are present in the added mountant before the coverslip is placed.

CRITICAL STEP: Care should be taken that no air bubbles are present in the added mountant before the coverslip is placed.- 7.

- Gently lower the silicone-covered coverslip onto the glass slide and trachea samples/mountant, then gently press into place. Care should be taken so that the silicone layer is the middle layer between the coverslip and the glass slide.

- 8.

- Use a Kimwipe or paper towel to collect any leaked mountant from the sides of the coverslip.

- 9.

- Seal the coverslip edges using quick-dry nail polish, then air dry at room temperature, protected from light, for 10–20 min.

- 10.

PAUSE STEP: Slides can now be stored at 4 °C before imaging (~1–4 days).

3.3. Fluorescent Imaging

CRITICAL STEP: To minimize fluorescence photobleaching when imaging, do not illuminate samples with bright white or fluorescence excitation light unless actively viewing or collecting images.

CRITICAL STEP: To minimize fluorescence photobleaching when imaging, do not illuminate samples with bright white or fluorescence excitation light unless actively viewing or collecting images.- Place the glass slide onto the stage of the fluorescence microscope.

- Use the microscope stage to position the sample in front of the microscope objective and focus using brightfield.

CRITICAL STEP: The coverslip should be the side facing the microscope objective, i.e., if using an upright microscope, the coverslip should be face up. If using an inverted microscope, the coverslip should be face down.

CRITICAL STEP: The coverslip should be the side facing the microscope objective, i.e., if using an upright microscope, the coverslip should be face up. If using an inverted microscope, the coverslip should be face down.- 3.

- Use green (FITC) epifluorescence, microscope eyepieces, stage controller, and focus knobs to quickly scan the sample and find a representative area of ciliated trachea epithelium to image.

- 4.

- Use the image collection software to optimize fluorescence collection settings (e.g., camera gain/laser power) as needed for each fluorescence channel (BLUE/FITC/TRITC). Image settings should result in images that are bright with minimal overexposure [25].

CRITICAL STEP: To optimize image collection, camera gain should be optimized for each different sample area imaged.

CRITICAL STEP: To optimize image collection, camera gain should be optimized for each different sample area imaged.- 5.

- Collect a three-colour (BLUE/FITC/TRITC) image z-stack. Use the green (FITC) channel to set the top of the image z-stack to just above the top of the cilia. Use the red (TRITC) channel to set the bottom of the image z-stack to just below the epithelial cell layer. The total z-stack depth should be ~12 μm if the epithelial layer is flat. The total number of images to collect within the z-stack will depend on the objective NA [26]. Two example three-colour image z-stacks can be found in the Supplementary Files.

- 6.

- Save image z-stacks on computer, making sure to include in file name sample/treatment information.

CRITICAL STEP: If saved image files do not contain imaging metadata, make sure to record in the lab book the microscope and camera settings used.

CRITICAL STEP: If saved image files do not contain imaging metadata, make sure to record in the lab book the microscope and camera settings used.3.4. Image Analysis

3.4.1. Image Optimization

- Open image z-stack using FIJI (FIJI 2.3.0/1.53q).

- Use the ‘Channels Tool’ (found in /Image/Color/Channels Tool; Shortcut Ctrl+Shift+Z) to set the colour for each channel (Blue for live/dead, Green for FITC, Red for TRITC).

- Use ‘Z-Project’ to collapse the z-stack into a single image for each colour channel.

- Use ‘Brightness/Contrast’ to optimize brightness for each colour channel, avoiding overexposure of pixel intensities.

- Use the ‘Channels Tool’ to display a merged image of all three colour channels.

- Save the image in TIFF format before cell counting.

CRITICAL STEP: To open this merged image in non-ImageJ software, the image file should be converted into a single RGB image by using ‘Stack to RGB’ in ImageJ before saving as a TIFF image.

CRITICAL STEP: To open this merged image in non-ImageJ software, the image file should be converted into a single RGB image by using ‘Stack to RGB’ in ImageJ before saving as a TIFF image.3.4.2. Image Analysis

- Open the three colour/channel z-projected image using FIJI (FIJI 2.3.0/1.53q).

- Use the ‘Multi-point’ tool to manually count the following by clicking on each cell:

- Total number of epithelial cells (using the red channel);

- Total number of ciliated epithelial cells (using the red and green channels);

- Total epithelial cells stained dead (using the red and blue channels);

- Total nonciliated epithelial cells stained dead (using the green and blue channels).

- OPTIONAL STEP: A range of automated cell counting plugins exists for ImageJ, which can automate the counting of dead stained cells, e.g., the ‘Cell Counter’ tool (found in /Plugins/Analyze/Cell Counter) or other custom plugins [28,29]. Unfortunately, these tools have not proved reliable in counting total epithelial cells using phalloidin staining, which only labels cell edges, or total ciliated cells using anti-acetylated tubulin antibody staining, which only labels the cilia. Recent advances in AI technology may make automated counting of these cells more practical.

- OPTIONAL STEP: Points can be saved using ‘ROI manager’ as a .roi file.

- Calculate the following from the above cell counts:

- Total number of nonciliated epithelial cells (by subtracting the number of ciliated epithelial cells from the total number of epithelial cells);

- Total ciliated epithelial cells stained dead (by subtracting the number of nonciliated epithelial cells stained dead from the total number of nonciliated epithelial cells stained dead).

- OPTIONAL STEP: To control for variability between samples, cell counts can be converted into percentages as outlined below:

- Percentage of epithelial cells with cilia (per sample);

- Percentage of epithelial cells without cilia (per sample);

- Percentage of total epithelial cells stained dead (per sample);

- Percentage of nonciliated epithelial cells stained dead (per sample);

- Percentage of ciliated epithelial cells stained dead (per sample);

- Percentage of dead epithelial cells stained dead that are ciliated (per sample);

- Statistical analysis of group numbers is then assessed using statistics of choice (e.g., ANOVA).

4. Expected Results

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABD | Antibody Dilution Buffer |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| FIJI | Fiji Is Just ImageJ |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen Peroxide |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PBSFS | PBS + 1% FBS |

| PBSGS | PBS + 5% Goat Serum |

| PBST | PBS + 0.2% Triton X |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| RGB | Red, Green, Blue, colour model |

| ROI | Region Of Interest |

| TRITC | Tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate |

References

- Whitsett, J.A. Airway Epithelial Differentiation and Mucociliary Clearance. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018, 15, S143–S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.D.; Wypych, T.P. Cellular and functional heterogeneity of the airway epithelium. Mucosal Immunol. 2021, 14, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, B.M.; Button, B. Structure and function of the mucus clearance system of the lung. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2013, 3, a009720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallmeier, J.; Nielsen, K.G.; Kuehni, C.E.; Lucas, J.S.; Leigh, M.W.; Zariwala, M.A.; Omran, H. Motile ciliopathies. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoyne, R.A.; Fisher, A.J.; Borthwick, L.A. The Role of Epithelial Damage in the Pulmonary Immune Response. Cells 2021, 10, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlier, F.M.; de Fays, C.; Pilette, C. Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction in Chronic Respiratory Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 691227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Gowers, K.H.C.; Lee-Six, H.; Chandrasekharan, D.P.; Coorens, T.; Maughan, E.F.; Beal, K.; Menzies, A.; Millar, F.R.; Anderson, E.; et al. Tobacco smoking and somatic mutations in human bronchial epithelium. Nature 2020, 578, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumont, M.; van de Borne, P.; Bernard, A.; Van Muylem, A.; Deprez, G.; Ullmo, J.; Starczewska, E.; Briki, R.; de Hemptinne, Q.; Zaher, W.; et al. Fourth generation e-cigarette vaping induces transient lung inflammation and gas exchange disturbances: Results from two randomized clinical trials. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2019, 316, L705–L719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, R. The effects of acute hydrogen peroxide exposure on respiratory cilia motility and viability. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groneberg, D.A.; Witt, C.; Wagner, U.; Chung, K.F.; Fischer, A. Fundamentals of pulmonary drug delivery. Respir. Med. 2003, 97, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, M.; Dong, D.; Xie, S.; Liu, M. Environmental pollutants damage airway epithelial cell cilia: Implications for the prevention of obstructive lung diseases. Thorac. Cancer 2020, 11, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gappa, M. Outdoor Air Pollution and Its Effects on Lung Health. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2025, 60 (Suppl. 1), S109–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricmont, N.; Bonhiver, R.; Benchimol, L.; Louis, B.; Papon, J.F.; Monseur, J.; Donneau, A.F.; Moermans, C.; Schleich, F.; Calmes, D.; et al. Temporal Stability of Ciliary Beating Post Nasal Brushing, Modulated by Storage Temperature. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, W.; Li, H.; Birk, R.; Nastev, A.; Kramer, B.; Klein, S.; Stuck, B.A.; Birk, C.E. Impact of Bepanthen((R)) and dexpanthenol on human nasal ciliary beat frequency in vitro. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 280, 3731–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, L.K.; Turgutoglu, N.; Allan, K.M.; Belessis, Y.; Widger, J.; Jaffe, A.; Waters, S.A. Comparing Cytology Brushes for Optimal Human Nasal Epithelial Cell Collection: Implications for Airway Disease Diagnosis and Research. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awatade, N.T.; Reid, A.T.; Nichol, K.S.; Budden, K.F.; Veerati, P.C.; Pathinayake, P.S.; Grainge, C.L.; Hansbro, P.M.; Wark, P.A.B. Comparison of commercially available differentiation media on cell morphology, function, and anti-viral responses in conditionally reprogrammed human bronchial epithelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradique, R.; Causa, E.; Delahousse, C.; Kotar, J.; Pinte, L.; Vallier, L.; Vila-Gonzalez, M.; Cicuta, P. Assessing motile cilia coverage and beat frequency in mammalian in vitro cell culture tissues. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 230185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.; Rutman, A.; O’Callaghan, C. Disrupted ciliated epithelium shows slower ciliary beat frequency and increased dyskinesia. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 34, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Richer, E.J.; Huang, T.; Brody, S.L. Growth and differentiation of mouse tracheal epithelial cells: Selection of a proliferative population. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2002, 283, L1315–L1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtman, J.W.; Conchello, J.A. Fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Methods 2005, 2, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, R. A Simple Method for Imaging and Quantifying Respiratory Cilia Motility in Mouse Models. Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, D.J.; Brown, C.M. Epi-fluorescence microscopy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 931, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, A.D. Confocal Microscopy: Principles and Modern Practices. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 2020, 92, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Sevilla, P.; Thompson, S.A.; Jaque, D. Multichannel Fluorescence Microscopy: Advantages of Going beyond a Single Emission. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 2022, 2, 2100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogama, T. A beginner’s guide to improving image acquisition in fluorescence microscopy. Biochemist 2020, 42, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handbook of Biological Confocal Microscopy, 3rd ed.; Pawley, J.B., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grishagin, I.V. Automatic cell counting with ImageJ. Anal. Biochem. 2015, 473, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansak, K.L.; Baum, L.D.; Ghosh, S.; Thapa, P.; Vanga, V.; Walters, B.J. PCP auto count: A novel Fiji/ImageJ plug-in for automated quantification of planar cell polarity and cell counting. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1394031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Kim, B.R.; Yu, W.; Moninger, T.O.; Karp, P.H.; Wagner, B.A.; Welsh, M.J. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins protect human airway epithelial ciliated cells from oxidative damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2318771121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Adcock, I.M.; Barnes, P.J.; Huang, M.; Yao, X. Bronchial epithelial cells: The key effector cells in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Respirology 2015, 20, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tools | Source | Catalogue# |

|---|---|---|

| Cork Dissecting Board | Agar Scientific (Stansted, UK) | AGL4121 |

| #10 Scalpel Blades | Roboz Surgical Instrument Co. (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) | RS-9801 |

| No 3. Scalpel Handle | Roboz Surgical Instrument Co. (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) | 65-9843 |

| Blunt Dressing Forceps | Roboz Surgical Instrument Co. (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) | RS-8100 |

| Dissecting Scissors; Straight; 5" Length | Roboz Surgical Instrument Co. (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) | RS-6808 |

| McPherson-Vannas Straight Micro Scissors | Roboz Surgical Instrument Co. (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) | RS-5602 |

| #4 Inox Dumont Tweezers | Roboz Surgical Instrument Co. (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) | RS-4904 |

| Rocking Plate | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) | 88882002 |

| Reagents (to purchase) | Source | Catalogue# |

| Kimwipes (12 × 21 cm) | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) | 25509-KL |

| P1000 Micropipette + tips | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) | 4641100N |

| P100 Micropipette + tips | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) | 4641070N |

| OPTIONAL Repeating Pipette with 25 mL tips | Eppendorf (Hamburg, Germany) | M4 or E3 |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) | 18912014 |

| 4% Paraformaldehyde in PBS (PFA) | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) | J61899.AK |

| Goat Serum | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) | 16210064 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) | 16000044 |

| Live/Dead fixable violet dead cell stain kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) | L34955 |

| SlowFade Diamond Antifade Mountant | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) | S36967 |

| Aluminum foil | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) | 040760.HP |

| 35 mm culture dishes | Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) | CLS430165 |

| 50 mL centrifuge tubes | Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) | CLS430829 |

| 12-well culture plate | Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) | CLS3336 |

| OPTIONAL Corning NETWELL 12-well plates | Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) | CLS3477 |

| Microscope Glass Slides (75 × 25 mm) | Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) | CLS294775X25 |

| Rectangular Glass Coverslips (24 mm × 50 mm) | Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) | CLS2975245 |

| Monoclonal Anti-Tubulin, Acetylated antibody | Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) | T6793 |

| Phalloidin Peptide-TRITC labelled | Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) | P1951 |

| Triton X-100 | Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) | X100 |

| Fluorescein (FITC) Goat Anti-Mouse IgG | Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA, USA) | 115-095-003 |

| Revlon Quick Dry Top Coat (nail polish) | Revlon (New York, NY, USA) | - |

| ~0.127 mm thick silicone sheet | AAA Acme Rubber Co. (Tempe, AZ, USA) | CASS-.005X24-65908 |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline with Triton X-100 (PBST): PBS + 0.2% Triton X-100 (100 µL Triton per 50 mL PBS) |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline with Fetal Bovine Serum (PBSFS): PBS + 1% FBS (0.5 mL FBS per 50 mL PBS) |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline with Goat Serum (PBSGS): PBS + 5% Goat Serum (2.5 mL goat serum per 50 mL PBS) |

| Antibody dilution Buffer (ADB): PBS + 5% Goat Serum, + 0.1% Triton X-100 (2.5 mL Goat Serum and 50 µL Triton X-100 per 50 mL PBS) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Francis, R. Optimized Whole-Mount Fluorescence Staining Protocol for Pulmonary Toxicity Evaluation Using Mouse Respiratory Epithelia. Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060146

Francis R. Optimized Whole-Mount Fluorescence Staining Protocol for Pulmonary Toxicity Evaluation Using Mouse Respiratory Epithelia. Methods and Protocols. 2025; 8(6):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060146

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrancis, Richard. 2025. "Optimized Whole-Mount Fluorescence Staining Protocol for Pulmonary Toxicity Evaluation Using Mouse Respiratory Epithelia" Methods and Protocols 8, no. 6: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060146

APA StyleFrancis, R. (2025). Optimized Whole-Mount Fluorescence Staining Protocol for Pulmonary Toxicity Evaluation Using Mouse Respiratory Epithelia. Methods and Protocols, 8(6), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060146