A Longitudinal Evaluation of an Intervention Program for Physical Education Teachers to Promote Adolescent Motivation and Physical Activity in Leisure Time: A Study Protocol

Abstract

:1. Introduction

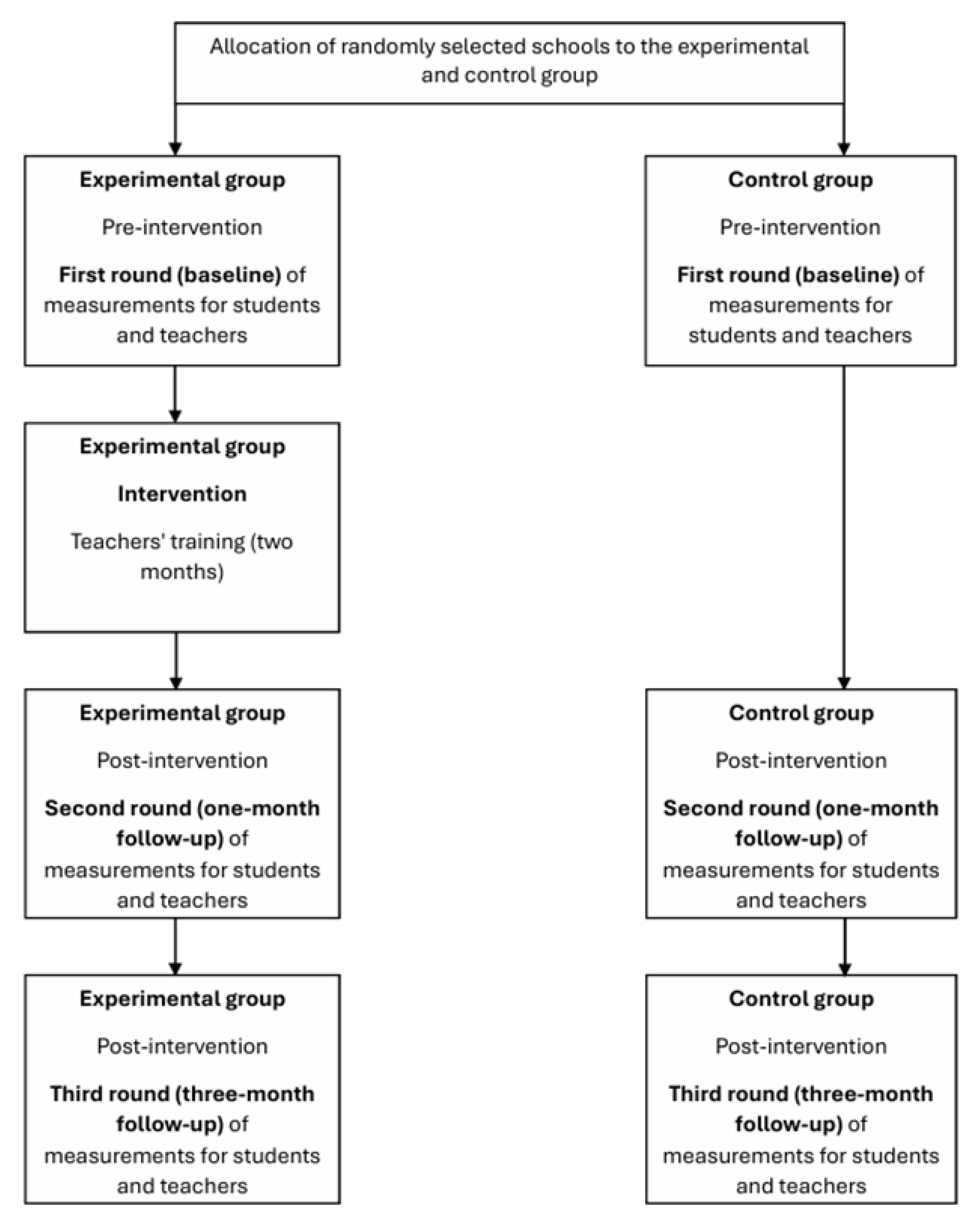

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Ethical Considerations, Consent, and Permissions

2.3. Interventions

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Behavioral Measure

2.4.2. Psychological Measures for Students

2.4.3. Psychological Measures for Teachers

2.5. Sample Size Calculation and Statistical Analysis

3. Expected Results

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Cadenas-Sánchez, C.; Estévez-López, F.; Muñoz, N.E.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Migueles, J.H.; Molina-García, P.; Henriksson, H.; Mena-Molina, A.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; et al. Role of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in the Mental Health of Preschoolers, Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 1383–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Ekelund, U.; Crochemore-Silva, I.; Guthold, R.; Ha, A.; Lubans, D.; Oyeyemi, A.L.; Ding, D.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Physical Activity Behaviours in Adolescence: Current Evidence and Opportunities for Intervention. Lancet 2021, 398, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.A.; Parkinson, K.N.; Adamson, A.J.; Pearce, M.S.; Reilly, J.K.; Hughes, A.R.; Janssen, X.; Basterfield, L.; Reilly, J.J. Timing of the Decline in Physical Activity in Childhood and Adolescence: Gateshead Millennium Cohort Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrovouniotis, F. Inactivity in Childhood and Adolescence: A Modern Lifestyle Associated with Adverse Health Consequences. Sport Sci. Rev. 2012, 21, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, E.; Woodfield, L.A.; Nevill, A.M. Increasing Physical Activity Levels in Primary School Physical Education: The SHARP Principles Model. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Culverhouse, T.; Biddle, S.J.H. The Processes by Which Perceived Autonomy Support in Physical Education Promotes Leisure-Time Physical Activity Intentions and Behavior: A Trans-Contextual Model. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. (Eds.) Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4625-3896-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J. Toward A Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997; Volume 29, pp. 271–360. [Google Scholar]

- Mäestu, E.; Kull, M.; Mäestu, J.; Pihu, M.; Kais, K.; Riso, E.-M.; Koka, A.; Tilga, H.; Jürimäe, J. Results from Estonia’s 2022 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth: Research Gaps and Five Key Messages and Actions to Follow. Children 2023, 10, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Demchenko, I.; Hawthorne, M.; Abdeta, C.; Nader, P.A.; Sala, J.C.A.; Aguilar-Farias, N.; Aznar, S.; Bakalár, P.; et al. Global Matrix 4.0 Physical Activity Report Card Grades for Children and Adolescents: Results and Analyses From 57 Countries. J. Phys. Act. Health 2022, 19, 700–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibar, A.; Chanal, J.; Zaragoza, J.; Generelo, E.; Bois, J.E. Physical Activity Differences between Two European Countries: Does Motivation Matter? Educ. Psychol. 2022, 42, 800–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-K.; Chen, S.; Tu, K.-W.; Chi, L.-K. Effect of Autonomy Support on Self-Determined Motivation in Elementary Physical Education. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2016, 15, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reeve, J.; Cheon, S.H. Autonomy-Supportive Teaching: Its Malleability, Benefits, and Potential to Improve Educational Practice. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 56, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilga, H.; Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Koka, A. Web-Based and Face-To-Face Autonomy-Supportive Intervention for Physical Education Teachers and Students’ Experiences. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2021, 20, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vaquero-Solís, M.; Gallego, D.I.; Tapia-Serrano, M.Á.; Pulido, J.J.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A. School-Based Physical Activity Interventions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paap, H.; Koka, A.; Meerits, P.-R.; Tilga, H. The Effects of a Web-Based Need-Supportive Intervention for Physical Education Teachers on Students’ Physical Activity and Related Outcomes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Children 2025, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polet, J.; Schneider, J.; Hassandra, M.; Lintunen, T.; Laukkanen, A.; Hankonen, N.; Hirvensalo, M.; Tammelin, T.H.; Hamilton, K.; Hagger, M.S. Predictors of School Students’ Leisure-Time Physical Activity: An Extended Trans-Contextual Model Using Bayesian Path Analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Polet, J.; Hassandra, M.; Lintunen, T.; Laukkanen, A.; Hankonen, N.; Hirvensalo, M.; Tammelin, T.H.; Törmäkangas, T.; Hagger, M.S. Testing a Physical Education-Delivered Autonomy Supportive Intervention to Promote Leisure-Time Physical Activity in Lower Secondary School Students: The PETALS Trial. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Boudreau, P.; Josefsson, K.W.; Ivarsson, A. Mediators of Physical Activity Behaviour Change Interventions among Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2021, 15, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Koka, A. Effects of a Web-Based Intervention for PE Teachers on Students’ Perceptions of Teacher Behaviors, Psychological Needs, and Intrinsic Motivation. Percept. Mot. Skills 2019, 126, 559–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J. A Classroom-Based Intervention to Help Teachers Decrease Students’ Amotivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 40, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J.; Moon, I.S. Experimentally Based, Longitudinally Designed, Teacher-Focused Intervention to Help Physical Education Teachers Be More Autonomy Supportive Toward Their Students. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 34, 365–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriz, R.; Jiménez-Loaisa, A.; González-Cutre, D.; Romero-Elías, M.; Beltrán-Carrillo, V.J. A Self-Determined Exploration of Adolescents’ and Parents’ Experiences Derived From a Multidimensional School-Based Physical Activity Intervention. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2021, 41, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Noetel, M.; Parker, P.; Ryan, R.M.; Ntoumanis, N.; Reeve, J.; Beauchamp, M.; Dicke, T.; Yeung, A.; Ahmadi, M.; et al. A Classification System for Teachers’ Motivational Behaviors Recommended in Self-Determination Theory Interventions. J. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 115, 1158–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerens, L.; Aelterman, N.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Soenens, B.; Van Petegem, S. Do Perceived Autonomy-Supportive and Controlling Teaching Relate to Physical Education Students’ Motivational Experiences through Unique Pathways? Distinguishing between the Bright and Dark Side of Motivation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Koka, A.; Hagger, M.S. How Physical Education Teachers’ Interpersonal Behaviour Is Related to Students’ Health-Related Quality of Life. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 64, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doren, N.; Compernolle, S.; Bouten, A.; Haerens, L.; Hesters, L.; Sanders, T.; Slembrouck, M.; De Cocker, K. How Is Observed (de)Motivating Teaching Associated with Student Motivation and Device-Based Physical Activity during Physical Education? Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2024, 1356336X241289911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriz, R.; González-Cutre, D.; Julián, J. Propuestas Didácticas Para Mejorar la Motivación en Educación Física y Desarrollar Estilos de Vida Saludable; Editorial INDE: Barcelona, Spain, 2023; ISBN 978-84-9729-423-2. [Google Scholar]

- Duda, J.L.; Williams, G.C.; Ntoumanis, N.; Daley, A.; Eves, F.F.; Mutrie, N.; Rouse, P.C.; Lodhia, R.; Blamey, R.V.; Jolly, K. Effects of a Standard Provision versus an Autonomy Supportive Exercise Referral Programme on Physical Activity, Quality of Life and Well-Being Indicators: A Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMA—The World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants; WMA: Ferney-Voltaire, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ICH Official Web Site: ICH. Available online: https://www.ich.org/page/efficacy-guidelines (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Evenson, K.R.; Catellier, D.J.; Gill, K.; Ondrak, K.S.; McMurray, R.G. Calibration of Two Objective Measures of Physical Activity for Children. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgic, J.; Dumuid, D.; Bengoechea, E.G.; Shrestha, N.; Bauman, A.; Olds, T.; Pedisic, Z. Health Outcomes Associated with Reallocations of Time between Sleep, Sedentary Behaviour, and Physical Activity: A Systematic Scoping Review of Isotemporal Substitution Studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aelterman, N.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Haerens, L.; Soenens, B.; Fontaine, J.R.J.; Reeve, J. Toward an Integrative and Fine-Grained Insight in Motivating and Demotivating Teaching Styles: The Merits of a Circumplex Approach. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 497–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diloy-Peña, S.; García-González, L.; Burgueño, R.; Tilga, H.; Koka, A.; Abós, Á. A Cross-Cultural Examination of the Role of (De-)Motivating Teaching Styles in Predicting Students’ Basic Psychological Needs in Physical Education: A Circumplex Approach. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2024, 44, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudas, M.; Biddle, S.; Fox, K. Perceived Locus of Causality, Goal Orientations, and Perceived Competence in School Physical Education Classes. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1994, 64, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Connell, J.P. Perceived Locus of Causality and Internalization: Examining Reasons for Acting in Two Domains. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire; UMass Amherst: Amherst, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, G.; Shephard, R. A Simple Method to Assess Exercise Behavior in the Community. Can. J. Appl. Sport Sci. J. Can. Sci. Appliquées Au Sport 1985, 10, 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Koka, A.; Tilga, H.; Raudsepp, L.; Hagger, M.S. Trans-Contextual Model Predicting Change in Out-of-School Physical Activity: A One-Year Longitudinal Study. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2022, 28, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro-Suero, S.; Van Doren, N.; De Cocker, K.; Haerens, L. Towards a Refined Insight into Physical Education Teachers’ Autonomy-Supportive, Structuring, and Controlling Style to the Importance of Student Motivation: A Person-Centered Approach. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerens, L.; Vansteenkiste, M.; De Meester, A.; Delrue, J.; Tallir, I.; Vande Broek, G.; Goris, W.; Aelterman, N. Different Combinations of Perceived Autonomy Support and Control: Identifying the Most Optimal Motivating Style. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2018, 23, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkoukis, V.; Chatzisarantis, N.; Hagger, M.S. Effects of a School-Based Intervention on Motivation for Out-of-School Physical Activity Participation. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2021, 92, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Marques, M.M.; Silva, M.N.; Brunet, J.; Duda, J.L.; Haerens, L.; La Guardia, J.; Lindwall, M.; Lonsdale, C.; Markland, D.; et al. A Classification of Motivation and Behavior Change Techniques Used in Self-Determination Theory-Based Interventions in Health Contexts. Motiv. Sci. 2020, 6, 438–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paap, H.; Koka, A.; Tilga, H. A Longitudinal Evaluation of an Intervention Program for Physical Education Teachers to Promote Adolescent Motivation and Physical Activity in Leisure Time: A Study Protocol. Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8020034

Paap H, Koka A, Tilga H. A Longitudinal Evaluation of an Intervention Program for Physical Education Teachers to Promote Adolescent Motivation and Physical Activity in Leisure Time: A Study Protocol. Methods and Protocols. 2025; 8(2):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8020034

Chicago/Turabian StylePaap, Hasso, Andre Koka, and Henri Tilga. 2025. "A Longitudinal Evaluation of an Intervention Program for Physical Education Teachers to Promote Adolescent Motivation and Physical Activity in Leisure Time: A Study Protocol" Methods and Protocols 8, no. 2: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8020034

APA StylePaap, H., Koka, A., & Tilga, H. (2025). A Longitudinal Evaluation of an Intervention Program for Physical Education Teachers to Promote Adolescent Motivation and Physical Activity in Leisure Time: A Study Protocol. Methods and Protocols, 8(2), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8020034