Abstract

At the entrance of some churches in Tuscany (Italy), the reproduction of an apparently undecipherable inscription can be found. Beginning in the 18th century, this epigraphic puzzle has originated a debate on its interpretation. This study proposes a hypothesis based on the Latin alphabet used in texts contemporary to the churches where the inscription is reproduced and a possible interpretation of the message consistent with the official religious doctrine. The proposed deciphering is extended to the full text, including some signs that were previously considered geometric forms or a specific elaboration of letters not attested in other contemporary documents.

1. Introduction

This paper is part of an active debate on the interpretation of a Medieval inscription carved on marble monuments and located near the entrance of many churches in Tuscany, Central Italy.

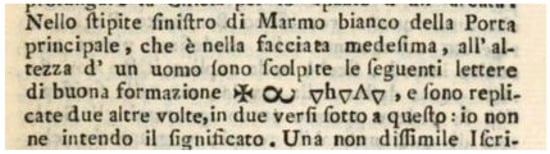

The inscription has a specific structure, showing a possible alternative to the symbols and letters. Its impenetrable nature attracted the attention of many glyph-breakers and has kept several “savants” engaged, such as the physician and naturalist Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti (1712–1783). Indeed, he described the puzzling inscription observed at the Duomo of Barga, a village located in a valley among the Apennines mountains, in the Lucca province, northern Tuscany (). A short extract of his study is reproduced in Figure 1, where he proposes a possible transcription. It is interesting to note that the reproduction is sometimes different from the real inscription in Figure 2. Indeed, the first letter after the cross is upside down, possibly to create a Greek omega. Despite Targioni Tozzetti translating many Latin inscriptions, in this case, he declared: “I do not understand its meaning” (… io non ne intendo il significato, the text in the last two lines in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Text from a book by G. Targioni Tozzetti, reproducing the puzzling inscription of Barga (Targioni Tozzetti 1768).

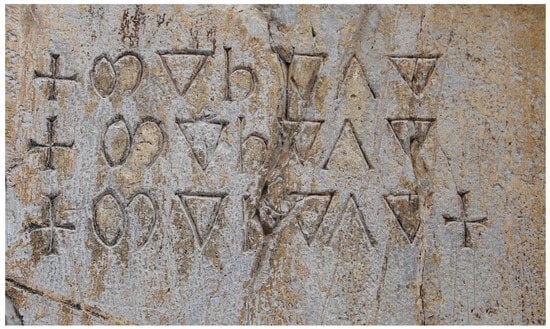

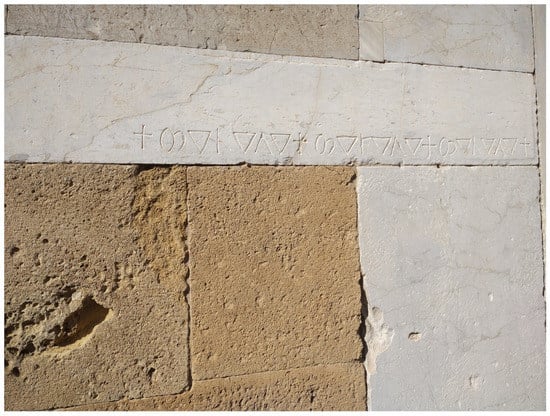

Figure 2.

Inscription from the Duomo of Barga, main entrance (T. Giannini—Barga 2023).

The inscription, represented in Figure 2, is composed of a set of six symbols, repeated three times, separated by crosses with equal arms (Greek crosses).

The version reproduced in Figure 2 is placed on the external wall of the main entrance of the Duomo of Barga (12th century). Barga, as mentioned, is a small center located in the province of Lucca in the Lunigiana Valley.

In the same church, another reproduction of the inscription exists, on the left jamb of the door on the right wall of the nave, represented in Figure 3.

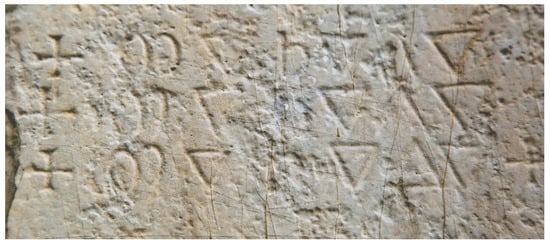

Figure 3.

Inscription from the Duomo of Barga, the door on the right of the nave (T. Giannini—Barga 2023).

This double presence is an interesting fact, and it is helpful to understand the role of this artifact. It looks closely related to the door and, probably, it was aimed at transmitting a message preparing people for their access to a holy place.

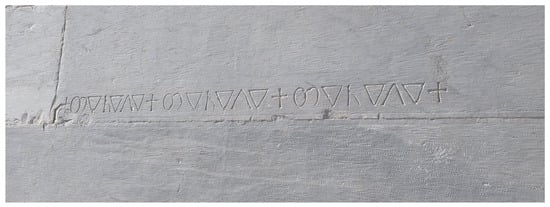

Another version of the inscription, with the entire text on a single line, reproduced in Figure 4, is attested on the jamb of the main door of the Baptistery of Pisa (12th century) ().

Figure 4.

Inscription from the Baptistery of Pisa, main door (M. Pierantoni—Proloco Barga 2023).

Additionally, in Pisa, there is another attestation of the epigraph on one side of the door of the San Frediano church (11th–12th centuries). This indicates a local distribution of religious buildings realized between the 11th and the 12th centuries in Tuscany.

A version split in three lines, similar to the Barga specimen, can be observed at the National Museum of San Matteo in Pisa, engraved on a stone that was originally in the church of the Cosma and Damiano Saints, a building now destroyed ().

The only document describing the inscription can be found in manuscript No. 896 (folio 63 recto), dating back to the 18th century, from the Biblioteca Governativa of Lucca (), the “Government Library of Lucca”. The document refers to the translation of the San Ponziano relics from Rome to Lucca in 901 (). On the lead box containing the body of the Saint, there was a copy of the inscription. Under every segment of the epigraph, the following words were added: Immensitas, Unitas, Veritas (“Boundlessness, Oneness, Truth”, three doctrinal references).

The content of the manuscript has generated some doubts about the date of the translation and the name of the individuals mentioned. The facts described, indeed, have no reference in the original documents from the Middle Ages. For this reason, the first appearance of the inscription in the 10th century has not been considered strong evidence of its origins.

2. Materials

2.1. Literature Review

A. Mancini recognized in the inscription the three letters “M, H, and A”, which are associated with acronyms of an apotropaic invocation: “m(alum) h(inc) a(vertatur)” (“keep away bad things”) or with a magic spell adopted by some workers involved in the building of churches in Tuscany in the Middle Ages, people extremely devoted to the Holy Trinity. Another interpretation proposed for the letters is m(isterium) h(oc) a(moris) (“this is a mystery of love”) ().

The famous epigraphist Margherita Guarducci proposed a detailed analysis. She confirmed the idea of a text related to the Holy Trinity in order to keep away the presence of Evil, but, instead of the Latin alphabet, according to her, the inscription would contain three Greek letters: mu (mi), eta, and lambda ().With reference to the epigraphic conventions of the reduction in names, the text would represent the Greek name Μικαηλ (“Micael”), in an invocation to Saint Michael.

If the third letter was considered an uppercase lambda, we would expect to find an eta also in upper case, and this is not what was observed.

Lastly, Ottavio Banti proposed the last and more commonly accepted deciphering attempt. The inscription would not be written in Greek, but in the Latin (Roman) alphabet, and all six symbols would be characters (). Banti read the name, Mihili, a variation introduced by the Lombards of the name of San Michele (Saint Michael). In the scholar’s opinion, the three triangular symbols would be the letter “i”, in a specific elaboration of style, and the fifth character, similar to an inverted V, would be an “L”, a rare form of the letter “L” from the 6th–7th centuries ().

On the same line of interpretation, Daria Pasini, in 2015, focused on the historical references. She proposed a detailed analysis of the date of realization of different versions of the inscription (). The first version was probably realized in the 8th century in the area of the current Lucca province; this would justify the asserted archaic form of some letters suggested by Banti.

Another paper on the possible methodological approach to decipher this inscription has been recently published by Francesco Perono Cacciafoco (), with the aim of re-animating the debate on this epigraphic document.

Hana El-Shanawany proposed a new (slightly speculative) hypothesis on the meaning of the triangular symbols ().

2.2. Context

The symbols on the inscription are actually difficult to be recognized and interpreted. They look like archaic letters or not letters at all. This poses the question of whether the inscription was a cryptic message for a group of adepts or a possibly clearer message for all devout persons, with its meaning lost over time, with the loss of specific knowledge. The reproduction in many copies of the same inscription suggests that it was not an occasional realization engraved by local workers. Its position is always near a church door, at a height aimed at attracting human eyes and, therefore, being well-visible. The carving of an inscription in a religious building is, on a marble slab, a significant act, probably requiring the approval of ecclesiastical authorities, and it has to be related to Catholic doctrine ().

In Tuscany, during the 11th–12th centuries, the official religion was represented by the Christian Catholic confession with reference to Rome and the Latin rituals. It was, therefore, not directly connected with the Greek rituals of Byzantium, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. The language of the “clergy” for religious texts and ceremonies was, indeed, Latin ().

Reading and writing competencies in the European Middle Ages were skills almost exclusively limited to clerical scholars and some members of the dominant class, so it was common to hand down religious messages to the population through images, such as the frescos findable in many churches or the bas-reliefs on the façade of churches and their internal spaces (the so-called Biblia Pauperum) ().

In this context, it would be very important to achieve a precise estimation of the time of the first appearance of the inscription. As seen in the introduction, the document preserved in the National Museum of Pisa contains dubious references; therefore, the 10th century as the first attestation on a lead box is uncertain. An inscription carved in a church could be contemporary or successive to the date of its building, but, in the Middle Ages, it was a widespread habit to recover stones and architectural elements taken from previous buildings, so it is not impossible that the origin of the inscription is earlier than expected.

Figure 5 shows that the slab with the inscription from the church of San Frediano is very different from the stony material of the wall where it is inserted, and this could represent an example of architectural reuse.

Figure 5.

Inscription from the church of San Frediano, Pisa (M. Pierantoni—Proloco Barga 2023).

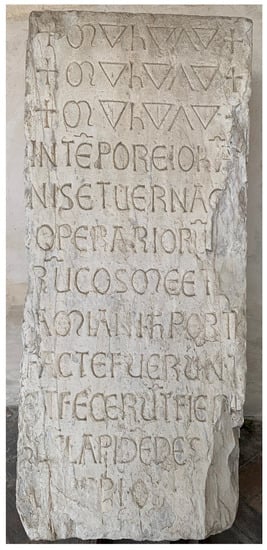

The inscription from the former church of Saints Cosma and Damiano, reproduced in Figure 6, provides us with some very useful details. In the upper part of the stone, the inscription is attested and, in the lower part, we can read a text that describes the realization of the doors of the church. This suggests a contemporary origin of the inscription and the building.

Figure 6.

Inscription from the former church of Saints Cosma and Damiano, now at the National Museum of Pisa (M. Pierantoni—Proloco Barga 2023).

The second inscription from the Duomo of Barga, in the jamb of a lateral door, is engraved on a material so similar to the architectural elements of the rest of the wall that it appears to be contemporary to (or slightly more recent of) the construction of the church.

There is no earlier date for the first appearance of the inscription, but the text was probably widespread in the 11th–12th centuries.

The aim of this research is to try to answer two questions: what alphabets were used in the inscription and what was the message vehiculated by it? A specific focus is given to contents widespread among the majority of believers in the 11th–12th centuries can easily be interpreted by them, possibly avoiding ad hoc solutions for the understanding of the single letters.

2.3. Method

Considering the shape, position, and number of symbols in the Barga inscription, it is possible to theorize that it is not a linear text like the one defined in O. Banti’s assumption. Only some symbols are clearly recognizable as letters of the alphabet, and they seem interposed with other symbols, at least at first look.

The crosses are an explicit religious reference and are used to separate the message, which is repeated three times.

The research process aimed at identifying all possible characters is based on an analysis of the epigraphic urban tradition and comparison with Medieval liturgical texts (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ).

A further step consists of the tentative extraction of a possible meaning from the letters in accordance with the rules of epigraphy and the examples from inscriptions produced between the 11th and 12th centuries on the Italian peninsula (; , ; ; ).

It is now useful to summarize some preliminary remarks:

- A text located near the door of a religious building, visible to all the believers, had to represent a significant message, potentially understandable by a general “audience” in a specific cultural and historical context ();

- The characters had to be part of the same alphabet, carved in the same version; this excludes the option of a mix of Latin and Greek letters, or a mix of recent and archaic writing styles; both could have represented, indeed, an unnecessary obstacle for the readers;

- In a church, it is normal to expect messages reinforcing the religious traditions, referring to episodes of dogmatic texts or figures relevant to the religious hierarchy ().

3. Results

3.1. Deciphering Proposal

The following analysis considers the group of six symbols reproduced in each line of Figure 2. It does not focus on the crosses, as they are supposedly a normal reference to the church and the religious context and not alphabetic characters.

The effort to associate letters with crosses that was tried during the development of this paper on the basis of previous studies did not produce any meaningful results.

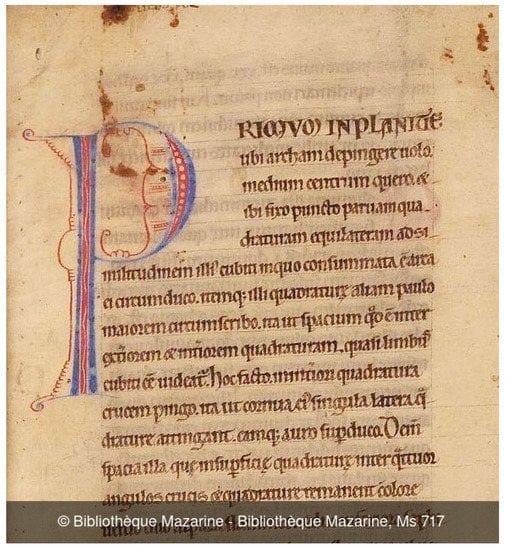

Based on a comparison of the inscription with a text from the 12th century that reproduces the incipit of a paragraph of a religious book by Ugo from San Vittore, in Figure 7, it is evident that the first and the third symbols of the Barga inscription directly correspond to upper case characters of the Latin uncial alphabet: the M and H letters.

Figure 7.

Bibliothèque Mazarine Paris Ms 0717, f093v, Hugues de Saint Victor, De vanitate mundi, 12th century. Text of the title: Primum in planitie ().

Originally, the uncial alphabet was a twelfth height of a foot size script, and it was adopted in manuscripts from the 3rd to the 8th century. Later, it was replaced by Carolingian, but it continued to be utilized over the centuries to write the first characters of paragraphs or titles.

Following the hypothesis of homogeneous alphabet characters, the fifth symbol should belong, therefore, to the uncial alphabet, and should be the letter A.

The shape of the possible M in the inscription is very specific to the epigraph and it seems to correspond so much to the uncial version that the theory of the use of the Greek alphabet, for the inscription, becomes very weak.

The last and most consistent confirmation of the interpretation of the three letters comes from the inscription found in the church of Saints Cosma and Damiano, visible in Figure 6. The letter “M” is repeated many times in the text below the inscription; the letter “h” is also present, and only the letter “A” shows a negligible difference, which provides us with the option of doubting that this can be solved only through a subsequent semantic analysis.

It looks difficult to accept the interpretation of the third character of the inscription, proposed by Banti, as a rare form of “L” from the 7th or 8th century. All three letters, indeed, are considered as if they were reproduced in the standard uncial in use in the 12th century. As additional support, the letter A was represented as an inverted V in some coins of the Ostrogoths and the Lombards, such as in the solidus of King Sico in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Solidus of King Sico (817–832), Mint of Benevento (): main side, bust of the king with the globus crucifer; reverse side, an image of Saint Michael Archangel with a crosier and the globus crucifer.

The second, fourth, and sixth symbols are triangular shapes with a downward vertex. They have multiple roles. They are symbols of the claws of Evil and, at the same time, they represent the letters “V” with a specific convention adopted in the Medieval epigraphic tradition explained in the analysis of the following text.

In some Lombard coins, a horizontal bar is added over a letter representing a vowel to indicate that a nasal consonant has to be added; therefore, “V” with an upper bar could indicate a sound “un” (). A similar convention is extended to traditional epigraphy, and the bar is a reference to an acronym; therefore, “V” plus a bar could represent words beginning with “uni” or with “ver”, (). Like in Latin, indeed, “V” can represent both the phonemic variants “u” and “v”.

3.2. Interpretation of the Message

The Barga inscription, as it appears in Figure 2, is a complex mix of letters repeated exactly three times. Three lines with three repetitions of the same group contain three letters and three triangles. Four crosses are interposed, possibly to strengthen the evidence of the religious context.

The whole inscription could be interpreted as a graphical composition aimed at sending a message both to the literate and the majority of illiterate believers ().

The illiterate worshippers, indeed, could easily recognize and understand a graphical composition containing repeated symbols. During the rituals, the clerics probably explained with accuracy the correct meaning of the epigraph. This complex group of symbols was, possibly, effective in attracting the attention of the believers. Today, in Pisa, a popular belief survives: the three triangles in the inscription are considered marks of the claws of Evil, driven back away by crosses and by the formula contained in the text. This could be confirmed if the sound “un”, represented by a “V” with a bar, was an abbreviation for the Latin word unguis, meaning “nail” (plural ungues = “nails”).

The author of the inscription appears to be interested in vehiculating a powerful message to the point of adopting a specific solution. He represents the concept of the aggression of Evil with a graphic image of the claws on the wall and an alphabetic text at the same time.

In the inscription, the alphabetic letters are “M, H, A” in the form of acronyms in accordance with the epigraphic tradition. However, in the absence of more information, every Latin word beginning with the corresponding characters could be proposed, and this originates potentially endless (and arbitrary) options. A solution could be achieved by analyzing the religious tradition and some of its specific aspects, such as the habit of the believers to call for help from intermediary figures between human beings and God, i.e., the Saints, a custom that is widespread in the Catholic tradition.

Unexpected support for this comes from some inscriptions attested in the early European Middle Ages. When books were so rare, another form of writing was used in everyday life and was intentionally utilized as a tool of propaganda for political and religious ideas: the art of coin inscriptions.

After the deposition of the last emperor of the West Roman Empire, Romulus Augustulus, at the end of the 5th century (476), a diffusion of coins minted by new rulers suddenly occurred on the Italian peninsula; first, the Ostrogoth kings, then, the Lombard rulers in the 6th–8th centuries, and, finally, the Francs in the 8th–9th centuries.

The Lombard invaders of Italy minted their first coins as an imitation of the Empire ones. For a long time, the coins were not very accurate reproductions of Imperial coins and, sometimes, they were carrying meaningless texts. Only during the reign of Cunipert (688–700) did the coins assume a distinctive iconography: the introduction of the king’s name, on one side, and, on the other side, the winged figure of Saint Michael, the saint patron of the Lombards.

An example of the image of Saint Michael is evident on the solidus of King Sico in Figure 8. One side shows the image of the King, and the reverse shows the Saint with a crosier in his right hand and the globus crucifer on the left. The text Michael Archangelu Conob contains the name of the Saint and Conob, an imitation of the Byzantine mints to indicate golden coins from Constantinople.

In the Bible, Saint Michael the Archangel is the chief of the army of the angels, a warrior; his cult became widespread in Italy mainly irradiating from the monastery of San Michele on the Gargano in Apulia ().

Some interesting acronyms on the Lombard coins connected with Saint Michael are:

- -

- “M H”, to indicate Michael Archangelus, represented on a denarius of King Adelchis (Anno Domini 853[-878]);

- -

- “MIHA”, to indicate Michael Archangelus, on a denarius of Radelchis II (Anno Domini 881[-884]) ().

These coins are only one example of the importance of Saint Michael in the Catholic tradition. The original tomb of Emperor Adrianus, located near the Vatican in Rome, is, today, named Castel Sant Angelo in honor of Saint Michael, the Defensor of Vatican City.

The devotion to Saint Michael, indeed, acquired an increasing importance in most of Europe during the Middle Ages, as the Saint represents the defense of Faith against Evil. This idea was supported by an apocryphal text, The Assumption of Moses, which describes a contentious argument between the Saint and Evil to keep “ownership” of the body of Moses.

Evidence of the significance of this fight can be found in a letter by Saint Bruno from Cologne (1030–1101), an intellectual of the 12th century, quoted by G. Marangoni (). The letter states … Michael pugnat cum Diabolo principe Daemoniorum (“Saint Michael fights against the Devil, prince of Demons”). This reference also confirms that the form Michael for the name of the Saint was in use in the 11th–12th centuries ().

The epigraphic tradition to use acronyms and the relevant role of Saint Michael support the hypothesis that the inscription with M H A may be read as:

MicHael Archangelus.

In the Catholic tradition, when a demonic presence was active, it was mandatory to keep it apart and call the Saints to help. The position of the inscription near the door of religious buildings, and, in a specific case, the double inscription at the Barga Duomo, confirm the ritual role of the epigraph.

The inscription could have been, therefore, an invitation to call Saint Michael Archangel three times before entering the sacred building. The Saint could protect the believers against bad influxes and Evil ().

The choice of the number “three” is not arbitrary but has, from very remote times, a special meaning in spiritual rituals and beliefs.

In the religious tradition of the European Middle Ages, repeating the Psalms three times was a recommendation from the book Rationale Divinorum Officiorum (1280 ca.) and, specifically, in the Latin text, tres salmos dicimus ().

Another implementation of the number is inherent in the three words added under the inscription in the manuscript of Lucca: immensitas, unitas, and veritas; they are a reference to three relevant characteristics of God and are related to the three letters “V” with upper bars. Individuals who had solid cultural and religious backgrounds in the Middle Ages, such as priests and monks, could read in the abbreviations “un” and “ver” and the mystic words unitas, universitas, and veritas, or similar lexical items.

In Medieval Christian rituals, after all, there is a tendency to give a relevant position to the Saints, but this could lead to suspects of heresy and, therefore, a reference to the unity of God was always necessary ().

4. Discussion

The choice to compare the puzzling inscription from Tuscany with religious texts from Medieval documents has led to the hypothesis that the epigraph analyzed here contains an invocation to the Archangel Saint Michael, and the three Latin letters M, H, and A in every group of symbols are acronyms of Michael Archangel.

In addition, the three letters “V” should be marked with a convention, widespread in the epigraphic context, which makes the letters difficult to be recognized. The meaning of these letters is complex and may be references to Evil and divine properties.

In the representation of the three claws of Evil scratching the wall of a church and a Saint who drives back the Evil itself, it is possible to see a plastic image of the temptation, which, possibly, was very impressive for the believers (; ).

This image is reinforced by “anatomical” details. The Evil has three anterior claws, as it is a bird of prey. In Medieval frescoes representing Saint Michael or Saint George killing the dragon, the animal does not have the characteristics of a reptile, but it has two wings and feet with the claws of a bird. The idea of temptation was symbolically related, indeed, to flying beasts, such as the Roman Harpies.

The religious message of the inscription is connected with many concepts from the culture and beliefs of the European Middle Ages:

- -

- The use of apotropaic texts near the door of a house was widely adopted during the Roman era, especially against catastrophic natural events. In the Middle Ages, the triple call to Saint Michael, who fights a dragon, recalls the fear of Evil influxes, which always require a divine “champion”, to be defeated;

- -

- A believer calls for the aid of the Saint in the form of purification. It is evident from the inscription on the Baptistery of Pisa that Saint Michael and the Christening are both media to save the souls;

- -

- Saint Michael is a warrior, and in an era of general violence, when society was dominated by a group of warriors, his figure became extremely popular;

- -

- The contrast described in the inscription of Barga is between two angels: Saint Michael, the chief of “divine” angels, and Evil/Lucifer/the Devil, a fallen and rebellious angel;

- -

- The repeated reference to the number three highlights the special role of this number in the religious context of the European Middle Ages. More than one thousand years earlier, it was already part of the rituals of the Etruscan and Raetic peoples, populations that were at the origins of the proto-historic cultural substrate of the Italian Peninsula where the towns of Lucca and Pisa are located;

- -

- Symbolic and cultural elements may have more than one meaning, such as the text “un” being represented three times in the inscription. It contains a reference to the demonical temptation in the word unguis/ungues and a divine quality, represented by the Latin word unitas.

The puzzling inscription contains the Latin alphabet in a version used in the 11th–12th centuries when, in some churches of Tuscany, the believers had the opportunity to observe it every time they entered the religious facility.

The main subject of the epigraph is a very significant figure, Saint Michael the Defensor, against the temptations represented by Evil.

The believers call the Saint three times in an apotropaic request to be protected, implicitly recognizing their (human) weakness, a concept widely diffused in Christianity ().

A complete understanding of the epigraph is very difficult to achieve because the text includes a superimposition of two opposite concepts, with elements mutually alternating: the name of Saint Michael and the reference to the Evil represented by its claws. This probably was a designed symbolic effect, implemented to foreshadow the dramatic fight between Saint Michael and Evil.

5. Conclusions

The puzzle of the Medieval inscription from Tuscany is a fascinating one. It attracted attention in the past and is still the object of an interesting debate. Due to the extremely short length of this epigraphic text and its symbolic nature, it is very difficult, or even impossible, to say the “final word” on its interpretation.

However, scholars have been able, over time, to propose significant theories on its origins and its meaning, which, possibly, have moved more and more toward its complete explanation.

This paper provides its readers with a comprehensive interpretation of the inscription, which takes into account the previous deciphering attempts and tries to consider the epigraph in its historical (and paleographic) context. The hope is to offer scholars and readers an original contribution, which can trigger further debate and discussion to get even closer to the truth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.V.; methodology, S.V.; validation, S.V. and F.P.C.; formal analysis, S.V.; investigation, S.V.; resources, S.V.; data curation, S.V.; writing—original draft preparation, S.V. and F.P.C.; writing—review and editing, F.P.C. and S.V.; visualization, F.P.C.; supervision, F.P.C.; project administration, S.V.; funding acquisition, F.P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Barga Proloco for the support they provided with images and pictures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allegria, Simone. 2010. Manu mea subscripsi. considerazioni sulla cultura scritta ad Arezzo tra ix e inizio xi secolo. Scripta 3: 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi, Gino. 1955. Attorno ad una iscrizione su tre chiese di Pisa e sul Duomo di Barga. La Provincia Di Pisa III: 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi, Gino. 1956. Attorno ad un’antica iscrizione sulla tomba del martire S. Ponziano, in Il nuovo corriere. Il Nuovo Corriere 15: 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Banti, Ottavio. 1975. Simbolismo religioso e stilizzazione grafica in una iscrizione longobarda del secolo VIII. Studi Medioevali XVI: 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- Banti, Ottavio. 1995. Epigrafi medievali pisane nel Museo Nazionale di San Matteo. In Scritti di Storia, Diplomatica ed Epigrafia. Edited by Silio P. P. Scalfati. Pisa: Pacini Editore, vol. 1, pp. 181–98. [Google Scholar]

- Banti, Ottavio. 2000. Monumenta Epigraphica Pisana Saeculi XV Antiquiora. Pisa: Pacini Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Bosisio, Matteo. 2016. Nephandi criminis/stupenda qualitas. L’ Ecerinis di Mussato tra meraviglioso e demonologia. In Aspetti del meraviglioso nelle letterature medievali. Aspects du merveilleux dans les littératures médiévales: Medioevo latino, romanzo, germanico e celtico. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, pp. 105–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelli, Adriano. 1929. Dizionario di abbreviature latine e italiane. Edited by Ulrico Hoepli. Milan: Hoepli, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Costambeys, Marios. 2012. The laity, the clergy, the scribes and their archives: The documentary record of eighth- and ninth-century Italy. In Documentary Culture and the Laity in the Early Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 231–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debiais, Vincent. 2019. Visibilité et présence des inscriptions dans l’image médiévale. In Visibilité et présence de l’image dans l’espace ecclésial. Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, pp. 357–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Saint Victor, Hugues. 1141. Recueil de textes d’Hugues de Saint-Victor. De Vanitate Rerum Mundanarum Ms0717, f 093v. Available online: https://bibnum.institutdefrance.fr/records/item/1896-recueil-de-textes-d-hugues-de-saint-victor?offset=6 (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Durando, Guillaume. 1612. Rationale Divinorum Officiorum (Sumptibus P. R. Apud Haeredes Gulielmi Rouillii, Ed.). Apud Haeredes Gulielmi Rouillii, Sumptibus Petri Rousselet. Available online: https://archive.org/details/rationalediuinor01dura/page/n539/mode/2up?q=dicimus (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- El-Shanawany, Hana. 2022. The decipherment of the inscription of the baptistery of Pisa. Academia Letters 3360: 1–3. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/51125775/The_Undeciphered_Inscription_of_the_Baptistery_ (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Farinelli, Roberto. 2008. Archeologia urbana a Grosseto. Il contributo delle epigrafi e dei testi epigrafici (secoli XIII-XIV). Ricerche Storiche 111: 137–88. [Google Scholar]

- Favreau, Robert. 1969. L’épigraphie médiévale. Cahiers de Civilisation Médiévale 12: 393–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favreau, Robert. 1989. Fonction des inscriptions au Moyen Age. Cahiers de Civilisation Médiévale 32: 203–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favreau, Robert. 1997. Epigraphie Médiévale. Turnhout: Brepols, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Giove Marchioli, Nicoletta. 1994. L’epigrafia comunale cittadina. In Le forme della propaganda politica nel Due e nel Trecento. Relazioni Tenute al Convegno Internazionale di Trieste, (2–5 marzo 1993). Available online: https://www.persee.fr/issue/efr_0000-0000_1994_act_201_1 (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Gramigni, Tommaso. 2012. Iscrizioni medievali nel territorio fiorentino Fino al XIII Secolo. Firenze: Firenze University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graziosi, Gianni. 2022. Cenni di storia e monetazione longobarda. Available online: https://www.panorama-numismatico.com/wp-content/uploads/CENNI-DI-STORIA-E-MONETAZIONE-LONGOBARDA.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Guarducci, Margherita. 1959. La misteriosa iscrizione medioevale di Pisa, Barga e Lucca. Atti Della Accademia Nazionale Dei Lincei XIV: 216–24. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreau-Jalabert, Anita. 2003. L’ecclesia médiévale, une institution totale. In Les tendances actuelles de l’histoire du Moyen Âge en France et en Allemagne. Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, pp. 219–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, Jean. 1997. Les inscriptions chrétiennes de la gaule méridionale. In Actes du Xe congrès international d’épigraphie grecque et latine. Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, pp. 141–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Chiara Maria. 2004. Pagine di Pietra. Manuale di epigrafia latino-campana tardoantica e medievale. Salerno: CUES. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, Augusto. 1956. Ancora sull’iscrizione criptografica di Pisa e di Barga. Atti Dell’Accademia Nazionale Dei Lincei XI: 134–36. [Google Scholar]

- Marangoni, Giovanni. 1763. Grandezze dell’arcangelo San Michele. Gallarini. Available online: https://www.google.it/books/edition/Grandezze_dell_arcangelo_San_Michele_etc/9dZYAAAAcAAJ?hl=it&gbpv=1&dq=grandezze+dell%27arcangelo+michele&printsec=frontcover (accessed on 6 August 2022).

- Mazzoleni, Danilo. 1986. Le ricerche di epigrafia cristiana in Italia. In Actes du XIe congrès international d’archéologie chrétienne. Rome: École Française de Rome, pp. 2273–99. [Google Scholar]

- Morandi, Alessandro. 2001. Due brevi note di epigrafia italica. Revue Belge de Philologie et d’histoire 79: 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pani, Laura. 2015. Manuscript Production in Urban Centres. In Urban Identities in Northern Italy (800–1100 ca.). Turnhout: Brepols, vol. 2, pp. 273–306. [Google Scholar]

- Pasini, Daria. 2015. Daria Pasini Ancora sull’epigrafe con triplice invocazione di Pisa e Barga. Rivista Di Archeologia e Restauro 10: 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pastoreau, Michel, and Claudia Rabel. 1998. Histoire des images, des symboles et de l’imaginaire. In Les tendances actuelles de l’histoire du moyen âge en france et en allemagne. Paris: Edition la Sorbonne, vol. 1, pp. 595–616. [Google Scholar]

- Perono Cacciafoco, Francesco. 2021. The Undeciphered Inscription of the Baptistery of Pisa. Academia Letters 3359: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, Armando. 1971. Origine e diffusione del culto di San Michele nell’Italia medievale. In Millénaire monastique du Mont Saint-Michel. Edited by Marcel Baudot. Washington: Catholic University of America Press, pp. 339–52. [Google Scholar]

- Petrucci, Armando. 1973. Scrittura e libro nella Tuscia altomedioevale. In Lezioni Spoletine. Spoleto: Centro Italiano di Studi Sull’alto Medioevo, pp. 627–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pinsent, Andrew. 2018. The History of Evil in the Medieval Age 450–1450 CE. London: Routledge, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Targioni Tozzetti, Giovanni. 1768. Relazioni d’alcuni viaggi fatti in diverse parti della Toscana per osservare le produzioni naturali e gli antichi monumenti di essa. Firenze: Edizioni G Cambiagi. Available online: https://www.google.it/books/edition/Relazioni_d_alcuni_viaggi_fatti_in_diver/bGdiywAACAAJ?hl=it (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Wroth, Warwick William. 1911. Catalogue of the Coins of the Vandals, Ostrogoths and Lombards, and of the Empires of Thessalonica, Nicaea and Trebizond in the British Museum: British Museum. Dept. of Coins and Medals: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming: Internet Archive. London: Longmans & Co. Available online: https://archive.org/details/catalogueofcoins00britrich/page/n3/mode/2up (accessed on 5 September 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).