Abstract

Deserts confuse, fogging memory and electrifying the imagination. In 1853, on Utah’s Sevier River, a ritualized killing spawned a folklore of deserts that lives on to this day. Captain John W. Gunnison, an engineer, had detoured into an ambush. Dismembered, decapitated, his heart torn from his chest, he had died, it was said, by order of the Mormon prophet and Utah’s Latter-day Saints. Fabulized over the decades, the tale was contorted with an evil king in a desert kingdom, with ghoulish assassins and restless corpses undead. Folklore saw what historians have been slow to perceive about hauntings in desolation. Memories of trauma run deep in disquieting strangeness. Places presumed to be empty set dark expectations for horror.

1. Introduction

Geography was destiny, even a curse, in the grim remoteness of the Utah barrens where U.S. Army Captain John Williams Gunnison died. On 26 October 1853, on Utah’s Sevier River, the captain had staggered through a fury of arrows, killed among the carnage of seven men in his command. One trooper escaped by plunging into the river. Another, half dead, thrown from his horse, burrowed into sagebrush until the screams dissolved into silence. Soldiers later found what appeared to be Gunnison’s thighbone. A headless torso had been knifed through the heart.

“Barbarously Murdered then Maimed” was the Utah headline. “Indian Treachery. Revolting Cruelty. The Most Brutal Outrage Ever Committed”.1 But why the mutilation, with legs amputated and arms axed off at the elbow? Where were the corpses? Why had a jury acquitted the killers? Even now, the murders beguile.

John Gunnison, an explorer, an engineer, had wandered into a blood feud. Killed in barrens presumed to be empty, he had died, it was said, in a fight he knew nothing about. Embellished, the story went gothic in Victorian times with tropes from mystery fiction: a butchery, a boneyard desecration, a lock of blood-matted hair sent to a grieving widow, a gasping corpse with a thumping heart. What literature saw that engineers found hard to measure was malice of the strange and uncanny in Utah’s most desolate places. “You must be careful”, Gunnison had reported, awestruck. Emptiness seemed to “vibrate” as salt flats floated before you. Sticks appeared to be giants, and sometimes “a man walking alone will multiply into a troop marching with beautiful military exactness. Imagination lends a frightful aid”.2

Deserts, Gunnison knew, goaded the phantasmagoric. Hauntings gave narrative form to shape-shifting nebulous landscapes. Beyond the Great Salt Lake in the vibrating air of a trembling desert was blankness on which to compose.

2. Phantoms and Conspiracy Theories

Deserts overwhelm with fear and misinformation, Gunnison’s desert more so than most. From 1853 to 1857, south of the Great Salt Lake at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, its horror had curved like a hook through the heart of the Mormon county, bearing three great American fables. One featured a golden sea to the promise of California. Another had a priestly cabal of vigilante assassins. A third blamed innocent men for the bloodiest slaughter of Christians in the history of the overland trails. Seeding conspiracy theories, conjuring ghosts, the three great fables converged in Gunnison’s misadventure, for the engineer, it was said, had died at the gates of the golden passage, killed by those same assassins. Metaphysics rooted those stories. All parables of wilderness crossings, of sacrifice and ordeal, they unleashed from the dark subconscious a terror of austere blankness. Horror rushed in to structure how history came to be told.3

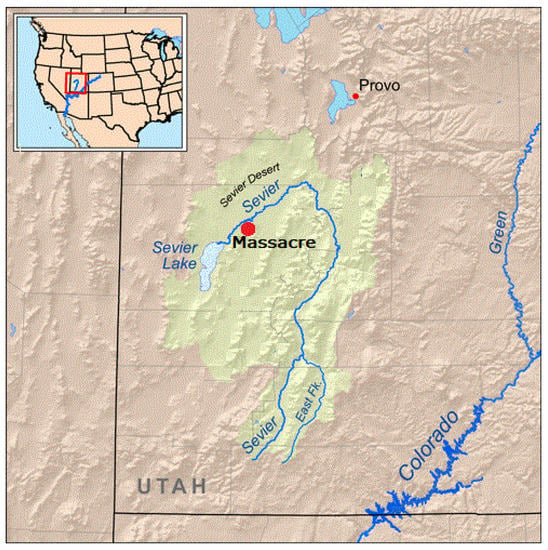

French-Canadian trappers had called the blankness sauvage, meaning chaotic, naming the steppe for its principal river (Figure 1). Spaniards said severo, meaning violent or severe. Anglicized, the basin became Sevier (se-VEER). Utah’s largest interior drainage, its watershed the size of Vermont, the Sevier fanned alluvial silt of alkali, chalk, and gypsum, flowing into one of the last of America’s unmapped places, an enigma in Gunnison’s time. Somewhere west of Fillmore, in Utah’s Millard County, the snowmelt suddenly vanished as if sucked underground by whirlpools. Travelers hallucinated. Flatness conspired with distance to distort human perception. Heat bent surreal light into the sheen of a glinting mirage.4

Figure 1.

Gunnison massacre site above Sevier Lake in Utah’s Millard County. Credit: Kmusser/Shallat.

Pahvants, a subtribe of the Utes, were said to have taken their name from the sump of the hooking Sevier, the sink where the delta dissolved. Pah was said to mean water. Vant meant vanished or gone. Vanishing water may also explain a grid of serpentine lines on a cliff near the Gunnison campsite—a prehistoric river treaty, perhaps. Above, on a crumbling ridge, is a tall black fracture of lava—a chimney for the devil, say some; the Great Stone Face of Latter-day Saint Joseph Smith, say others. Pahvant Butte, farther south, an 800-foot dormant volcano, marked the Old Spanish Trail in pioneer times. Beyond, in the powdery scrub, were placenames of trepidation. Confusion, a range of mountains. Skull Rock, a trail through Confusion. Devil’s Kitchen. Devil’s Gate. Devil’s Armchair. Hellhole. Misery. Disappointment. Little Sahara.

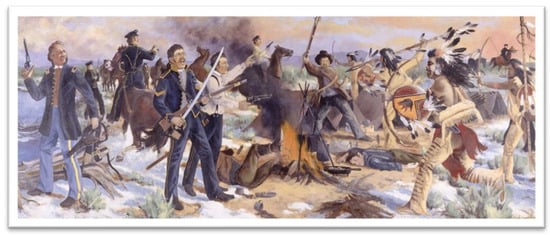

Phantoms menaced those badlands. In September 1853, near Fillmore, a millworker had bolted awake with a nightmarish premonition about a massacre that only he would survive. Seven weeks later came the shock of the Gunnison rampage (Figure 2). Pahvant warriors freely confessed. It was an eye-for-an-eye act of retribution, they said, for the murder of an Indian elder. But why Gunnison? A captain in the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, a West Pointer, he had been exploring a desert railroad. Skeptics looked north to Salt Lake City, where Brigham Young, the Mormon prophet, sat in the governor’s mansion and presided over the rising Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-day Saints. Young, it was said, feared rails would corrupt with a flood of nonbelievers; or, in an alternate telling, he wanted the route turned north through the Valley of the Great Salt Lake.5

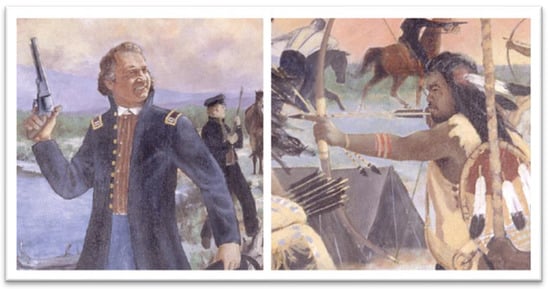

Figure 2.

Detail from “The Gunnison Massacre” by Frank M. Thomas, Millard County Fairgrounds, 1996. Credit: Frank Thomas Gallery.

Another whisper maligned the recent unwelcomed publication of Gunnison’s politely differential historical treatise concerning Utah’s Latter-day Saints. The book had been one of the first to detail the Mormon doctrine of plural marriage. Young, it was said, had the engineer snuffed as payback.

“I have always held myself that the Mormons were the directors of my husband’s murder”, wrote Martha Gunnison, the engineer’s widow.6

Murder, yes, and coldly premediated in the tale as it came to be told by a man widely hated in Utah. In 1855, William W. Drummond had traveled from Chicago to Millard County to preside as an ill-tempered federal judge. Blatantly immoral, a “libertine”, a “rotten-hearted loathsome reptile”, a “wolf”, a “jackass, a “peacock”, Drummond had shocked the pious people of Fillmore by arriving for work with a brute of a knife-wielding negro servant and a “scarlet lady”, a “strumpet”, too provocatively rouged to be any man’s Christian wife. Within a year, Drummond was gone. In flight via Carson City, having absconded with government horses, having threatened a man with a bullwhip, the runaway judge had gone to the New York Times with a zero-evidence theory about Mormon hitmen behind Gunnison’s tent. Allegedly, they were Sons of Dan, or Danites, alias Brigham’s Destroyers, a truth squad of bearded avengers, the prophet’s own palace guard. Drummond claimed a Danite sniper had signaled the ambush. Corpses had been left to the wolves to hide the bullets in Gunnison’s chest.7

Few academics ever believed it. Hubert Bancroft’s History of Utah (1889) rejected the rumor of Mormon assassins, calling it “entirely false”.8 But still the story grew thoroughly tangled. “No credible [Gunnison homicide] investigation was ever conducted”, wrote Robert Kent Fielding, formerly a BYU history professor, fired in 1961 for refusing to tithe the church. Three decades later, now retired, he fired back hard in a meticulous book of conspiratorial innuendo. Prophet Young, Lion of the Lord, stood accused of sheltering Gunnison’s killers. His minions were roundly denounced for scrubbing the historical record. Sadly, the professor lamented, the faithful were “calves in a stall” and primal in their need to believe that the Lord’s anointed prophets were incapable of any injustice and guiltless of any offense.9

And so the mystery was mired in rancor and ancestor worship. Keepers of Gunnison’s flame downplayed the killings as randomly accidental. Others saw in the slaughter a prelude to the 1857 rebellion that came to be called the Utah War.10 Nothing was said of hauntings or psychic vibrations or the phenomenological process through which mental and material deserts comingle in gruesome events. Historians have yet to connect the hook of the Sevier to the fabulation of horror. Deserts, nevertheless, bedevil. The more boundless the space, the more ghostly and enigmatic, the more distance hazes perception. Footprints dissolve. Objects elongate. Rivers seem to deny the common logic of nature. Logic deconstructs to account for the chaos of abnormal things.

3. Mapping the Strange

Gunnison’s strange desert of torment pulled American geographical science off the map and beyond the army’s empirical world. A wasteland, a wagon passage, it was the highest and driest of North American deserts, the largest and least populated, the most disparaged and misunderstood. The Great Basin, explorers called it. The Big Empty. The Big Quiet. The Void. It was “stricken dead and turned to ashes”, said Mark Twain of Utah-Nevada.11 “Fierce and dull…[an] abomination” was that steppe at the foot of the Rockies in Owen Wister’s first cowboy novel. A “mean ash-dump landscape”, there was “no portion of earth more lacquered with paltry unimportant ugliness”. August heat beat down as if the barrens were roofed with zinc. No refuge for the restless yeoman who pined for forested landscapes. Not a teardrop of wholesome water in a mile of alkali sand.12

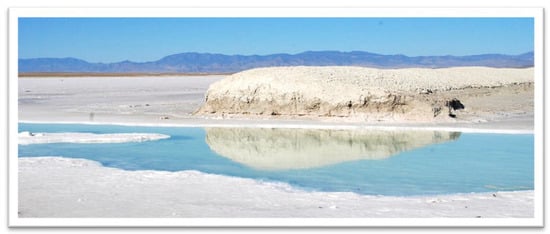

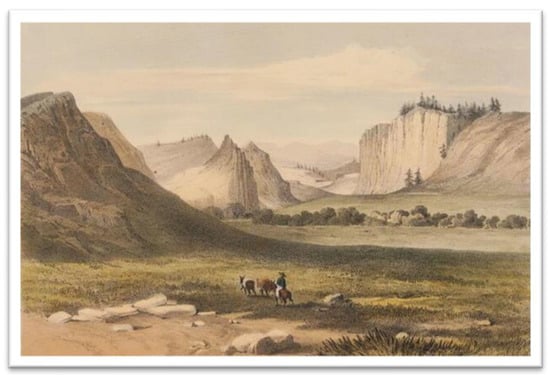

It was here, some 14,500 years before, that Lake Bonneville split desolation in one of history’s most massive floods. Swirling and crashing north into the Snake-Columbia drainage, carving chasms, tossing boulders larger than bison, the Bonneville Flood left prairies salted with playa lakebeds. The largest remnant with standing water is Great Salt Lake. Second is the Dead Sea of Millard County (Figure 3), also known as Sevier Lake. Forty years have passed since the windswept playa held snowmelt enough to pool even ten feet of water. Salt glistens crystalline-white like 27 miles of snow cones. Google Maps colors it blue, but do not expect a dockside campground. A red-lettered sign warns campers away from the shoreline. The county sheriff wants $500 to tow your rig from the muck.13

Figure 3.

Sevier Lake’s glittering salt flat. Credit: Jennifer Huntington.

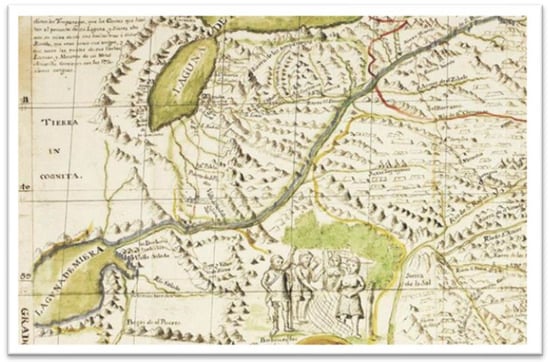

Once, it had seemed that the Sevier’s ethereal lakebed held water enough to validate Columbus’s dream of a passage from Europe to Asia. So said Father Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, a Spanish Franciscan. In 1776, on a search for that Great River to the Great Sea that would somehow link New Mexico to California at Monterey Bay, Escalante and nine companions had set out from Santa Fe. Father Francisco Atanasio Domínguez co-led the expedition. A second companion was Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco, age 62, a mapmaker and engineer, a retired cavalry captain. Miera went on to fame for an illuminated map that was among the first to tally a census of Indian nations. Hydrographically, nevertheless, the map proved its maker to be as dumbfounded as any in the befuddled western tradition of jumping to the wrong conclusion about how water seeped through deserts. Deductive simplicity overwhelmed observable facts.14

Still, Domínguez-Escalante-Miera trekked farther into the raw unknown than Daniel Boone’s trip through Kentucky, farther even than Lewis and Clark. On 30 September 1776, the Franciscans reached the Sevier River, naming it for the patron saint of neglected people, Santa Ysabel. From a willow hut, there emerged a wizened old man with a puzzled expression. “He was alone”, Escalante reported. “He had a beard so full and long that he looked like one of the ancient hermits of Europe”.15 Vaguely, with gesturing hands, the hermit seemed to confirm the existence of a “beautiful river”. Exactly where, the travelers wanted to know. Somewhere, the hermit replied. It was a river thought to be “very large and navigable” with civilized Indians in opulent cities.16 Its current was said to run west, perhaps feeding the western sea.

Dawn rose the following day to the sudden arrival of 20 talkative natives who looked even more European. Nomads without pueblos, they seemed “docile and affable”, even “joyous”. Holes bored through the cartilage of noses held polished ornamental bones. Men wore knee-length shirts and ropelike blankets that seemed to be twisted from the fur of rabbits. Most wore impressive beards. Yutes Barbones (long-bearded Utes), the friars called them. Tyrangapui, they called themselves. Could these innocents possibly be from the colony of lost Europeans who, according to Spanish legend, built seven great cities of gold? “They are very poor”, wrote Escalante, dismissing the legend. “They use no arms, other than arrows and some lances of flint, nor have they any other breastplate, helmet or shoulder-piece than that which they brought out from the bellies of their mothers”.17

Whether or not Escalante saw Sevier Lake is an open question. The Utah History Encyclopedia (1994) has the Franciscans preaching a lakeside sermon. But anyone who felt underfoot the crunch of the crusted playa would find it hard to believe that the friars came anywhere near it. Probably they camped to the east, no closer than 50 miles. Perhaps a scout had climbed a butte for a glimpse of the fabled ocean. Perhaps a ripple of light had shimmered on the western horizon. Perhaps the explorers, desperate for water, saw what they needed to find.18

“At times we saw a fairly good mirage in the distance”, said a newsman from Millard County, backtracking Escalante in 1931. “For all the world it looked like real water. [It was] very fooling so real did that fake water appear”.19

That illusion, whatever the source, inspired profound cartographic confusion. Miera’s 1777 Map of the Territories Newly Discovered brightly drew Sevier Lake like the rounded head of a tadpole with a long swimming riverine tail (Figure 4). The sketchy Santa Ysabel, redrawn, became a fat, wavy, blue-green line named Rio de San Buenaventura. It drained, that fantasy river, from the Green River of Wyoming-Utah to an estuary or sea or lagoon cut short by the edge of the page. Laguna de Miera, the mapmaker humbly called it. “By my calculations”, Miera estimated, “140 leagues (330 miles) remained to reach Monterey”.20 Today, via interstate, the distance is 1500 miles.

Figure 4.

Rio Buenaventura feeds into Sevier Lake’s Laguna de Miera, 1777. Credit: University of New Mexico Press.

“Faith is to believe what you do not see”, wrote St. Augustine, anticipating Miera. “The reward of this faith is to see what you believe”.21

And so it was with the legend of the Buenaventura. It measured in the wake of Miera what cartographers were prepared to believe. In 1804, the faithful were richly rewarded in Baron Drummond von Humboldt’s monumental map of New Spain. The illustrious baron, having pledged never to be hoodwinked by hearsay, transposed Miera without attribution, faintly sketching a yawning shoreline parallel to Monterey. Humboldt hand-delivered the map to President Thomas Jefferson, who passed it to Captain Zebulon Pike, who hunted the hypothetical river as far west as the peak in Colorado that now bears his name. By 1823, in Henry Tanner’s New American Atlas, the Buenaventura stretched 800 miles.22

Mountain man Jedediah Smith surely knew better. Rivers of wonder and other torrents of Miera’s imagination might have vanished from geography textbooks had the Rocky Mountain trapper survived to publish a journal. But Sevier Lake confused even Smith. One dubious story has the frontiersman building a lakeside fort for 100 American trappers. Another has beaver tycoon William Ashley naming the lake for himself.23

It remained for Captain John Charles Frémont of the army’s topographical corps to puncture the most inflated of western legends. In 1843–1844, on a covert mission for a secret committee of Congress, the topographer had circumnavigated some 200,000 square miles of northern Mexico, appraising that treasure for conquest. California bedazzled, but the return trip east across the Mojave was as dreary as the playas were bright. “No river from the interior can, or does, cross the Sierra Nevada”, Frémont reported. The “Great Basin”, as he coined it, was self-contained and concave. Its rivers all drained inward. There was no Rio de San Buenaventura. No outlet to Monterey Bay.24

Frémont, like Miera before him, like Gunnison nine years hence, never quite reached the sink of the Sevier but paid a toll, nonetheless. Yuba Dam now backfloods the upstream channel where the explorer lost a loyal companion. François Badeau, a French-Canadian scout, had grabbed the wrong end of his Hawken rifle and shot himself point blank.25

Perhaps it was here, in the backflow of the river’s damnation, that the curse of the place had passed to the red-faced Prussian who witnessed the fatal mishap. Charles Preuss, Frémont’s cartographer, had been determined as any meticulous man on a mission to resolve, once and for all, the conundrum of the vanishing Sevier. Instead, in his 1848 map of the Sevier drainage, Preuss jinxed the barrens again with a fresh set of misconceptions. A southern range of fantasy mountains appeared. A tributary of Sevier Lake (the Beaver?) was misdirected into the mile-long misspelled Pruess Lake of central Utah. Melancholy, morose, the mapmaker never really recovered. Back home, on the fringe of the capital city where Franklin Pierce sat in the White House, Preuss found a tree, knotted a rope, and ended his life.26

Meanwhile, under radiant skies in the haunting Utah strangeness, geography paused to reset. Sage and sand pushed back on the Jeffersonian myth of wet and boundless croplands. Dehydration was that paradigm lost. “No wood, no water, no grass”, wrote Frémont of the basin scrublands.27 No inhabitants save “diggers” and “lizard eaters”.28 Not a good place for cotton, surely. Not a great basin for farmers who knew nothing about pump irrigation. Rebranded in the nation’s frustration, the void was now negative space.

Even so, Congress wanted hard information. Was there water enough for a railroad? And where was Miera’s mirage?

4. Bad Water

The Emptiness Factor. It pulled the farmer who followed the trapper and was followed again, in turn, by steamboats and railroads in the art prints of Gunnison’s time. No saloon framed a print of scrubgrass. God’s Mistake, the mythmakers called it, that Sahara where progress derailed.29

Emptiness, a sneer, a conqueror’s justification, is today the gear-grinding basin-and-range of U.S. Highway 50 (Figure 5), an outback of bullsnakes and UFO mothership sightings, America’s “loneliest road”.30 Seven comatose hours from Delta to Fallon, Nevada, it flanks Sevier Lake to the north. “Totally empty”, frowns an auto club travel agent. “We don’t recommend it. There are no points of interest. We warn all motorists not to drive there unless they’re confident of their survival skills”.31 Stop at the Border Inn on the Nevada line for dollar slots and “I Survived Route 50” tee shirts. The Ritz it is not, but pass at your peril. Next gas: 91 miles.

Figure 5.

Lonely U.S. 50 near Austin, Nevada. Credit: Sydney Martinez/Travel Nevada.

That loneliest of hypnotic highways spans 11,000 years at least of diaspora and social migratory adaptations: the bison hunters, the mound builders, the pottery makers, the horsemen who preyed on the horseless, the Danish converts to Mormonism who plowed through the pottery shards. Near Sevier Lake are graves from the century of Julius Caesar. A male skeleton, recently excavated, faces up with palms open in muted surrender, seemingly astonished to have been found in a place presumed to be vacant. Flint axes, finger rings, lacquered baskets, clay dolls, and ceramic pipes for the smoking of cured tobacco date from the epoch before Columbus, when the basin was colder and wetter than Utah is now. Archeologists estimate a native population of 20,000 in the land of the Utes on the eve of the Mormon conquest. “Emptiness, for me, [is] absurd”, writes Dylan Mace, a scholar of Millard County, his roots stretching back to the Danes who settled near the massacre site.32

Emptiness was seldom empty of fables, surely. One from the storybook of Paiute tradition has a clumsy young water-born god in a wasteland of mishap. He carries a great sack of squirming people. The sack spills open. The people scatter.33

Likewise, in the Book of Mormon, a book of curses and omens, the dark and the savage are scattered for straying from the one true faith. Lamanites, so-called, they are the seed of Laman, a biblical villain. They cross the ocean on barges. Their skin is tarred with blackness. Surviving on uncooked meat in brush shelters, they degenerate and transmute into Utah’s aboriginal people. Utes, Paiutes, Shoshones, and Goshutes, they numbered perhaps 1000 in Millard County in the year of the Gunnison rampage. Brigham Young found them “loathsome” and “full of mischief”, and yet he allowed that God had marked them as allies. If converted from hunters to farmers, if won over with bread and kindness, the Lamanite brethren might one day become, said Young, “a white and delightsome people”.34 Whiteness, like rain and redemption, would follow the pilgrim’s plow.35

The irony was that a brainy New Englander of slight stature and ruddy complexion had a similar take on Latter-day Saints. Topographer John Gunnison, in 1852, had independently published a cautiously hopeful report on the state of Christianity’s progress in the kingdom called Deseret. Gunnison found Mormons “peculiar” but potentially Christian enough to redeem negative space. Mormonism, a “priestly tyranny”, was said to be “harmless” and “on the defensive”. Emptiness hemmed it in. Winter snows effectively shut off the Mormon corridor via Wyoming and Colorado. As for the government’s railroad, that “great cause”, that “crowning work of the century”, it was impartial and far removed from blood feuds.36 So said the soon-to-be-martyred lieutenant in the stillness before the ambush that proved his analysis wrong.

In 1853, the year the stillness shattered, it was Corn Creek’s fated misfortune to be midway between Brigham Young in Salt Lake City and the promise of cotton farming in and around St. George. It was here, in the Pahvant Valley at the base of the Pahvant Mountains, that Escalante had been so joyously overwhelmed by the tearful Yutes Barbones. Sons of their native sons still wore sharp-pointy beards when Gunnison saw them. Daughters still tended creekside gardens of short-eared Mexican corn. Jackrabbits and purple beans supplemented the protein. So did pronghorns, bighorns, deer, duck eggs, lizard eggs, grasshoppers, fish, bee larvae, and more than 100 edible species of roots, berries, and bulbs. Goshute women descended from the juniper highland with tall willow baskets of pinion nuts to be roasted and consumed by the fistful. Green minty tea from the leaves of sagebrush calmed headaches and rheumatism. A tart yellow porridge for upset stomachs mashed ricegrass with pickleweed seeds.37

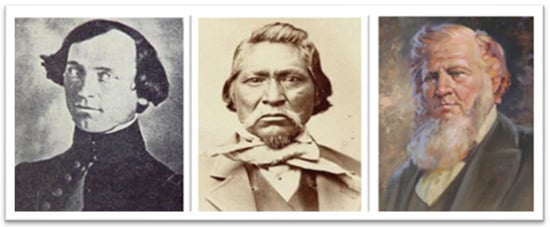

It fell to Chief Kanosh of the Corn Creek Pahvants to be man-in-the-middle in the place-in-between (Figure 6). Kanosh never met Gunnison, so far as we know, but the murder of one sparked the fame of the other as the Indian noble enough to recover a dead man’s pistol, watch, and notebook. Thereafter, in Millard County, waving back from parades and holiday pageants, Kanosh the Friend of the Whiteman was scripted to play The Last of the Sevier’s Mohicans, the Chief Joseph who, overwhelmed, vowed to fight no more forever, the Hiawatha who, seeking peace, drifted offstage as the sun of history set on the doom of his vanishing race. The shadow of that persona in the literature of historical revisionism was Kanosh the Mormon puppet, defeated, baptized, ordained. A sycophant, that Kanosh, he had bartered his Indian soul for a cabin, buggy, and top hat. As he aged, it was said that his skin spotted like a pale leopard, losing its pigmentation. Doctors blamed a fungal infection. Saints said Lord God had fulfilled His promise by suspending the curse of Laman, making Kanosh delightsome and white.38

Figure 6.

John W. Gunnison (left) from an ambrotype photograph, 1853; portrait alleged to be Kanosh, about 1870; Utah Governor Brigham Young. Credits: Colorado Historical Society, Brigham Young University, Roscoe A. Grover.

Historians lament that the man-in-the-middle left no memoir or personal papers. What we know comes from hearsay, mostly. Through folklore, nevertheless, we see Kanosh still in buckskins, age 25, riding into the mud village of Fillmore, a flintlock aimed at his head. It was 1853, a Friday in late September. The gunman had spent a frightful night shooting at phantoms from a circle of Missouri wagons on the trail from Salt Lake to Los Angeles. Gunfire near Scipio Pass had spooked the travelers into a panic. Wagon master Thomas Hildreth and his terrified greenhorns had vowed to shoot the next Indian regardless of tribe. “You infernal fool!” cursed Anson Call, bishop of Fillmore, as he slapped down the emigrant’s rifle. Kanosh was “the best loved Indian in the country”. Killing him would be suicidal. Within 24 h, said Call, brothers and uncles and the cousins of cousins would be leaping from every shadow. Only a dark “greasy spot” would remain.39

Kanosh—literally saved by Latter-day Saints in the tale as it came to be told—raced back to Corn Creek too late to head off the mayhem. A Pahvant elder was already dead. Old Toniff, a former chief, bent, grizzled, beloved, had approached the wagons in a trade delegation: one son, three women, and four or five others. They would stay the night, he insisted. It was Pahvant land, after all. Missouri greenhorns fingered their flintlocks. A sentry by the name of Hart made a grab for the old man’s arrow. Toniff pushed back, stabbing. One account has Hart jabbed in the stomach. Another has him shanked in the chest. Shrieking, falling back, Hart emptied his Colt revolver. Indians scattered, three of them wounded. Toniff, shot in the side, was chained to the wheel of a wagon. The next day, his sons found the corpse.40

And so it had sparked, the four-year spiral of violence, the fire that ignited the rampage that brought federal troops to Utah, damning Brigham Young in the court of public opinion, haunting Latter-day Saints to this day.

Had the Pahvants been a cohesively unified nation—had they been, say, Lakota Sioux or Chiricahua Apache—a pragmatic strongman of vision may have had the political muscle to snuff out the menacing flame. Kanosh, one chief of many, could not. An October entry in the diary of Anson Call records the predawn emergency meeting at which the saints of Fillmore offered cattle to the family of Toniff in blood-money compensation. Brothers and sons mostly agreed. All but one. “They [the Missourians] have killed my father; I will fight them”, seethed Moshoquop, a warrior, the son who had witnessed the shooting.41 Moshoquop the Avenger, he came to be called. Bereaved, inconsolable, he would return to the campsite, and there, dancing with shamans, communing with spirits, raise a multiethnic brigade of 20 or 30 young renegade fighters. They would hunt Old Toniff’s killers as far as justice required. At Cedar City, however, the plan collapsed when the Missourians fell in with an escort of Scottish frontiersmen. The renegades would have to regroup. They would winter in the waterfowl flyway, where the Sevier dissolved into salt flats. Uhvuh’pah (bad water), the Pahvants called it. No sane man would hope to find Moshoquop there.42

“Revenge is sweet and natural to the red man”, said a pioneer, his ranch about six miles east of Moshoquop’s brushwood tepee.43 “How cruel the red man is; how savage”, said another, as if no Christian had ever been vengeful, as if pigmentation was a precondition to be forever lusting for blood.44 What was racial was also spatial. Mark Twain of Missouri saw in Central Utah “that species of deserts whose concentrated hideousness shames [Africa’s] Sahara”. The most arid places, said Twain, bred a hybrid of kangaroo and African bushman, a race of “prideless beggars”.45 Naked places unlike the lush Mississippi were said to be the most depraved. Before reclamation, before Christian man could bestow the blessings of the Creator, New Eden would have to be cleansed.

“The Indians are sure to have their revenge”, Gunnison knew, having heard the story in Fillmore.46 Good thing he was headed in the other direction, moving west toward his scientific objective in The Empty that was anything but.

5. Into the Blackness

A glass-plate photograph shows Captain J. W. Gunnison, age 40, with a look of crazed foreboding in the blankness of dilated eyes. Wavy hair ducktails west, as if dust-blown toward California. A raised eyebrow under the high forehead of a receding hairline gives him the quizzical look of a man too tenaciously single-minded to be sidetracked by an Indian war.

Born in New Hampshire, schooled at West Point, he stood at the vanguard of American science at its golden moment of triumph, when desolation became a marvel of romantic fascination. At age 25, under enemy fire, he had hacked a timber highway through Florida’s Kissimmee swamplands. He had survived dysentery and yellow fever, mapped Michigan and Wisconsin, sounded Lake Erie, crossed on his back a stretch of Nebraska prairie in a spring-carriage ambulance wagon, shot out his own galloping horse while chasing bison in Colorado, triangulated and thereby confirmed with the certainty of astrometric computation that no Buenaventura drained west from the Great Salt Lake. Like John C. “The Pathfinder” Frémont, also a schooled engineer, the West Pointer had authored an important book and parlayed political connections into the choicest frontier assignments. Both had traveled far without straying from the West Point delusion that geographical science, being mathematical, was impervious to political bias. Gunnison, of the two, had proven the more able and cautious, having crisscrossed Colorado without once needing to admonish his troops for resorting to cannibalism.47

Gunnison and Frémont both had wondered what to make of the goosenecked river that vanished. Backwards, it was upside-down: its flow streaming north against the drainage of the Colorado, its basin concave like a range of mountains inverted, their watery peaks underground. “Ought to be called the severe valley”, said a pioneer saint in the year of the Mormon invasion. Army maps sketched only an outline of a Sevier lagoon as faintly as Humboldt had drawn it. Beyond, in bold block letters, the Great Sandy Desert was marked PAIUTE and UNEXPLORED. But still it beckoned, that largest last missing piece of God’s bizarre hydrographical puzzle. Missourians saw in that void the nation’s shortest and most practical line for a federal Pacific railroad. Minnesotans claimed St. Paul to Seattle was shorter. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, a Mississippian, supposed that any honest railroad survey would favor a flatter route through Arizona’s arid southwest. In 1853, with Congress deadlocked, the U.S. topographical corps sent the scientific brain of the army to resolve what politicians could not. There would be five simultaneous surveys. Gunnison, promoted to captain, would explore a 38th parallel route from St. Louis to San Francisco, crossing the Sevier ghostlands, bisecting what remained unexplored.48

On 23 June 1853, the Gunnison 38th Parallel Central Pacific Survey embarked from Westport Landing, where Kansas City crowds the levee today. Sixty men. Eighteen wagons. One-hundred-fifty-plus horses and mules in a 31-star armada of topographical instrumentation: of globes and beakers and tubes in brass-hinged mahogany boxes, of barometers, chronometers, thermometers, odometers, quadrants and sextants, rods and chains, bibles and navy revolvers, textiles and coins for the Indian trade. A mounted guard of 30 dragoons packed 0.54-caliber rifled muskets. There was also an artillery lieutenant, a botanist, an astronomer, a surgeon-geologist, a Comanche scout, a French-Canadian trapper, and an adventurous young landscape painter with a flair for the romantic sublime. Even for an era of grand scientific ventures, the 1700-mile wilderness survey, said a Boston reporter, “[was] the boldest…the most comprehensive…the most gigantic of any yet contemplated”.49

Not everyone thought Gunnison up to the hype. Not Frederick Creutzfeldt, expedition botanist, who despaired that “our ass of a captain” was marching in circles and into disaster.50 Not Missouri’s Thomas Hart “Old Bullion” Benton, five-term senator, Frémont’s father-in-law and patron who wanted The Pathfinder for Gunnison’s job. Benton had invested other people’s money in the promise of tunnels and trestles over the icy spine of Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. On 2 September, at 10,032 feet in Cochetopa Pass (Figure 7), geography voided that plan. Vertical chasms of cratered granite made jagged Colorado impractical for steam locomotion. The Great Transcontinental—that ribbon of steel the Union Pacific later completed—would have to run a northern 42nd parallel path via Iowa–Nebraska–Wyoming into the Valley of the Great Salt Lake.51

Figure 7.

Exploring Cochetopa Pass by John Mix Stanley from a sketch by Richard H. Kern, 1855. Credit: Amon Carter Museum.

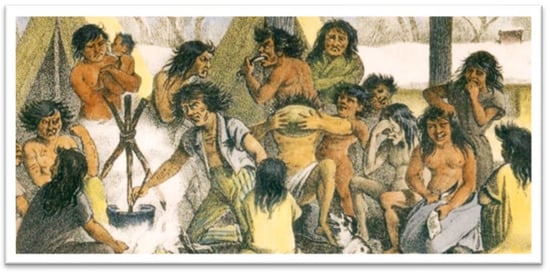

All had not been quiet on the Pahvant Front in the autumn of 1853 while Gunnison snaked through the Rockies. On 2 October, the Sabbath, the same dark day when Moshoquop stormed out of Fillmore, a militia of saints at the gates of Nephi gunned down a huddle of Utes begging for bread. Eight Indians died. A woman and two children were captured (Figure 8). At Spring Creek, now Springville, a fistfight left an Indian dead on the floor of a Mormon cabin. In Fillmore, a sniper cut down a sentry. Knifings, beatings, the stampeding of livestock, the sacking of gristmills and homesteads: it was terror so chaotically sporadic that historians have resorted to shorthand, blaming a single flamboyant outlaw, calling it Walker’s War. Chief Joseph Walker, his Mormon name, was elsewhere Wakara or Walkara, a Timpanogos Ute, a horse-rich kingpin of the Mexican-California slave trade. So fearsome was his persona, so long his cultural shadow, that folklore has twisted his tale with all manner of mendacious mayhem. Gunnison’s murder, for one. But the war named for Walker/Wakara, if war it deserves to be called, was sparked about where it died in the canyons above Lake Utah. Gunnison’s death, metaphysically speaking, was fury from another dimension. A reckoning, a crime of misperception, its pathos was peculiar to place.52

“There is a war going on between the Mormons & the Indians”, Gunnison wrote his wife in a hasty letter, his last. “We did not know what a risk we have lately been running. May the favor of Heaven attend us”.53

Figure 8.

Ute prisoners stockaded in Provo, 1852. Credit: U.S. Topographical Corps.

Signal fires tracked the engineer’s progress as he threaded the hook of the Sevier at the bend that now bears his name. Flurries dusted Pahvant Butte, an opaque whisper beyond the scrubgrass. Waterfowl squawked in the wetlands. On 25 October, with an advance patrol of seven troopers and four civilians, Gunnison found a thumb of beach in a screen of willows with adequate forage. He was two hours, maybe three, from whatever it was that Miera once saw. Undetected nearby were Moshoquop’s lakeside rebels. Ankle Joint, a Pahvant, a Moshoquop loyalist, elbowed through the rushes to find blue-coated squat-hatted men with flintlocks. One had a cavalry saber. Clearly not Mormons, these men. Mericats (Americans), he thought. Probably cutthroat kin to the killers who had shot Old Toniff. The hour of vengeance was nigh.54

Anthropologists would later make much of the fact that the Gunnison slayings were the first on record in which rebels-in-arms converged from distant places to stage a coordinated stealth attack. Sixteen were Corn Creek Pahvants. Others were Paiutes, Goshutes, Nevada Shoshone, and a Ute “buck” from Nephi. Hungry young men on the brink, 24 warriors in all, they shared no one single political grievance. Brigham Young called them “adolescents”. Kanosh said they were “boys”.55 Four or five may have had powder and lead for smoothbore muskets. There were also flint knives, stone axes, juniper bows, obsidian arrows, tall lances, the feathers and claws of animal spirits, deerskin and buffalo shields. Battle faces streaked crimson and white with pigments of ochre and limestone. On 26 October, in the cold early hours past midnight, they pranced and rhythmically chanted until the moon found a blanket of fog. Moshoquop, plunging forth, waved from his lance a false scalp of matted horsehair. Into the blackness, crouched in the ice, he inched into silvery willows not 50 paces from Gunnison’s tent.56

Daylight. A single shattering gunshot. A whoosh of arrows. Troopers scrambling, diving. John Bellows, the cook, dead at his kettle. William Potter, a civilian, a Mormon from Manti, swinging with the butt of a musket. Gunnison running, shouting. One story has the engineer firing a navy revolver, missing with all six shots. Staggered, he is shafted with 15 arrows. Speechless, eyes pleading, he crawls to a clump of saltgrass, props on an elbow then topples, shot point blank. The tale’s more gothic telling has Gunnison’s heart ripped from his chest. Plump with blood, pulsating, it rolls like a ball in the sand. Buzzards and wolves scatter around the carcass. It was doubtful that Moshoquop (Figure 9) even knew who Gunnison was.57

Figure 9.

Gunnison and Moshoquop details from Thomas’s mural. Credit. Frank Thomas Gallery.

It was done but far from over. “Who were the murderers?” the Missouri Democrat wanted to know, as it hazarded a conspiracy theory. Only Mormons had the means (the guns) and motive (the hatred), since, the Democrat said, “the whole tenor of their lives are [sic] such as to render them outlaws”.58 Pahvants were thought too simple to overwhelm U.S. dragoons. And besides, the Democrat added, Indians scalped. All but one of the slaughtered army surveyors still had full heads of hair.

It was Kanosh, again in the middle, who brokered a political deal: the United States would claim one Pahvant hostage for each of the slain surveyors, minus one for the life of Toniff. Four of the hapless seven were Pahvants too ancient to fire an arrow. Another was blind. Another was a nameless woman. A seventh was said to be mentally challenged and never made it to trial. Moshoquop the Avenger was not among them because, said Kanosh, he had stood on his Pahvant birthright. President Pierce sent an artillery colonel with 300 men to guard against insurrection. Chaos reigned, nevertheless. On 24 March 1855, in a Nephi courtroom, in a farce called noonday madness, an all-Mormon jury refused to condemn. Three of the Pahvants were outright acquitted. Three others were allowed to escape.59

No one needed a prophet to see that the Kingdom of Zion now faced a political crisis. “Mormon Interference” was the New York headline. “It was a time of war”, wrote Brigham Young, defending the verdict. “It cannot be expected of the Indian, in their present low and ignorant condition, with all their traditions and ferocious natures, to understand and act in accordance with the provisions of law which they never had the least knowledge of, nor any opportunity for obtaining such information”.60 Custom dictated that the son of a murdered man had a social duty, an obligation, to enforce lethal revenge. “Blood atonement”, the Mormon priesthood had called it. Eye-for-an-eye. Clan-versus-clan. Two years later, that same stark jurisprudence would come back to haunt, when copycat killings in a Utah ravine left 120 emigrants dead.61

Not until 1872 did a U.S. geographer reach Miera’s laguna to find, with anticlimax, no Eldorado, just the floor of a Pleistocene sea. Science still strained to explain the desert’s glinting hypnosis. Floating horsemen and pale stick-figure giants were dismissed as “optical defects” or “trembling air”.62 Physicists with weather balloons would later say alkali dust bent light into delusions. Jacob Schiel, army surgeon, had another theory. The sump in the sink of the Sevier, said Schiel, writing in his native German, was Satan’s back entrance to Hell.63

6. Talk to the Angels

Had the bodies been properly buried, had the Mormons raised a militia, had there been rifles enough in all of Utah to capture Moshoquop and hold him for trial, then, perhaps, the storm would have passed. Instead, it rained hard frustration. “Mormonism, this monster”, spat the New York Times. “Godforsaken”, it was “the grossest outrage…a curse too deep to tell”.64 Democrats and Republicans both stumped hard on “the Mormon question” when Pathfinder Frémont challenged James Buchanan in the 1856 presidential election. Mormondom was “wicked”, wrote W.W. Drummond in an open letter to the U.S. Justice Department.65 An “ulcer”, a “cancer”, said Stephen Douglas of Illinois, a presidential contender.66 Six months later, the Democrat Buchanan was in the White House, and a federal army of 2500 was slogging toward Salt Lake City with orders to depose Brigham Young.

Mormons prepared for the worst, sealing borders, stockpiling munitions, burning crops, abandoning farms. In August 1857, meanwhile, the Baker–Fancher emigrant train of 150-some pioneers in 40 Arkansas wagons rolled south against the flow of the Sevier on the Old Spanish Trail. Near Corn Creek, where Moshoquop had sworn his blood feud, a traveling LDS apostle had planted an explosive rumor: the emigrants, it was said, were using strychnine, or perhaps it was anthrax, to poison Kanosh’s water. The teenage son of a farmer had died. Down the road, a brigade of Mormons waited in ambush. Paiute allies called Piedes joined in for a cut of the spoils.67

On 7 September 1857, west of Cedar City in a clearing called Mountain Meadows, sniper fire at daybreak cut off the ear of a child. Four days of punishing siege left seven dead and sixteen wounded. Their water depleted, their dead decomposing in the baking heat of the wagon enclosure, the Baker–Fancher defenders agreed to lay down their arms. Then, in a blink, the unthinkable happened. Under a white flag of truce, as two lines of prisoners walked single file, a militiaman rose in his stirrups and shouted, “Do your duty!” Point blank, on cue, the captors turned on the captives, clubbing, stabbing, and shooting.68 Some 120 pioneers died (Figure 10), women, men, and children. Coyotes scattered their corpses for miles.

Figure 10.

Mountain Meadows Massacre, 1857. Credit: Barclay & Co. Credit: HWALKER597/Atas Obscura.

Mormons blamed Indian allies. Newspapers from New York to San Francisco were quick to blame Brigham Young. Again, it was said, the killers were white men in warpaint. Again, it was feared, the vipers would never face trial.

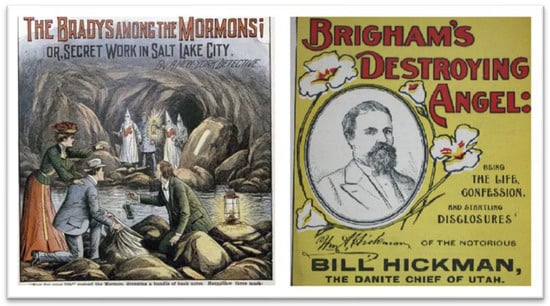

Massacres made good headlines—too good, perhaps, in the hook of the Sevier where things that never happened seemed too plausibly brutal not to be true. No Mormons killed army surveyors. No emigrants poisoned Kanosh’s water. No Pahvants took vengeance at Mountain Meadows. Thereafter, nevertheless, in print and on screen over the course of 17 decades, fables blurred and converged. Polygamists and priestly fanatics (Figure 11) sneered as they kidnapped and killed in a Zane Grey Mormophobe western and another by Joaquin Miller, in Paramount’s A Mormon Maid (1917), where mounted avengers are hooded like Klansmen, in Trapped by the Mormons (1922), where the latter-day undead drink a maiden’s virginal blood. Faceless, they were “goblins who strike at night in vengeance” in one Victorian thriller.69 Called Danites, also known as Brigham’s Destroying Angels, they returned post-9/11 in American Massacre (2003), September Dawn (2007), Hell on Wheels (2013), and Godless (2017). In No Time to Die, a 2021 James Bond sequel, a clean-cut assassin called Book of Mormon murders with a submarine bomb.70

Figure 11.

Danites murder and maim in “The Bradys Among the Mormons” (1903) and Bill Hickman’s incredulous memoir (1904). Credits: Juvenile Instructor; Shepard Publishing.

We need massacre stories, it seems, to settle unfinished business, to valorize martyrs, to recall that Satan has always been there to menace, to grapple with ethical questions about what constitutes murder in war. Massacres also reveal the power of ghostlands to self-fulfill expectations. “I’m getting a bad feeling. Really bad”, says Brett Carstens of California. A road-tripping psychic biker, bearded and bald, he has Suzukied across Nevada on the loneliest highway, traveling with spirit companions. Cosmic radiation draws them to the rusted pillar west of Hinckley, Utah, that now marks the Gunnison massacre site. “I don’t think my guys [the spirits] want me to be here. I’m picking up some wicked currents”. He is not sure who did what to whom, only that the Mormons did it. “I think it was murder. That’s what the spirits are saying”. Gasping, suddenly nauseous, he appeals to something unseen. “Talk to the angels”, he pleads. “If you need help, please talk”.71

Psychics drawn to Gunnison’s torment echo a Freudian thought about trauma deeply embedded in memories darkly repressed. Hauntings of the uncanny (das unheimliche in Sigmund Freud’s original German) are said to be a place-specific psychosis, a delirium triggered by fright. “Residual hauntings”, the hauntologists say.72 The Skinwalkers and Bigfoots and floating Victorian maidens. The hovering spacecraft. The ectoplasmic Other of murderous places where violence remains unresolved: at Idaho’s Bear River, for example, where a plaque cemented to stone blames the Shoshone for their own destruction; at Utah’s Ephraim, Birdseye, Pinhook Draw, and Salt Creek Canyon, where massacre markers list only the Christian dead. Fort Cove, south of Fillmore on the Old Spanish Trail, is said likewise to quiver with memory traces, for it was here that the rumor was planted of emigrants killing with strychnine, and here, in 1926, that townspeople staged a fantasy battle to honor the defenders of Zion. Farm boys disguised as Paiutes wore feathers and face paint. “The whites, they won that story”, said Eleanor Tom, a Paiute elder. “No one asked us for our account”.73

The whites, they won again in 1927, when Boy Scouts joined hands with Daughters of the Utah Pioneers on the slough called Gunnison’s Bend. There, a stone said to be sacred was consecrated to the memory of eight fallen U.S. surveyors. Nothing was said of Toniff. “Massacred by Indians” was stamped into bronze.74

7. Hopeless and Vast

Something is not quite right with the sharp-dressed mustachioed man in wide lapels and a saffron scarf. Glaring, darkly lacquered, he frowns from an oil-on-canvas in Fillmore’s Territorial Statehouse. Curators say the portrait is Kanosh. Archivists are less certain, because the image is an awkward copy of an unnamed, undated postcard. And the painting, besides, seems a shade of brown too red for the prophecy of the Pahvant made white. Above, in a nine-foot mural, is Corn Creek in the nostalgia before the convert Kanosh “was called” to abandon the valley. A curator’s note tells Kanosh’s tale as the story of three executions: a wife dragged to death by a pony, another murdered while hunting for rabbits, a third starved to death in a hut. The caption closes with an odd reminder that the Pahvants were never Nazis, despite blankets and baskets with patterns that resemble a swastika cross.

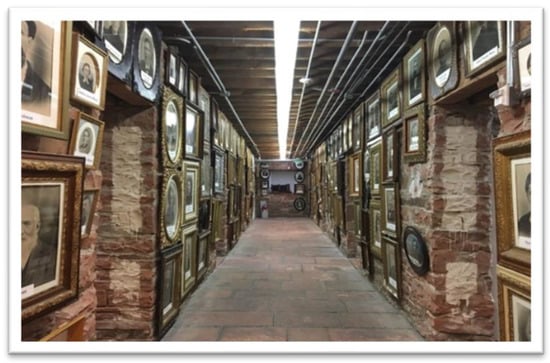

Something cold waits down the hall in the building’s sandstone basement. The jail has no door. The leg irons bolt to flagstones. Rectangles and ovals of golden rococo are triple-stacked ceiling-to-floor with gaunt rheumatic faces (Figure 12). The patriarchs. The scowling matrons. Cheekbones tinted with a pinkish pigment like cadavers in open caskets. “We check for ghosts every day”, says Ranger Carl, curator, a twinkle breaking his deadpan. Outside, in a hoodie and six inches of snow, is a stout young man with a camcorder and three kinds of poltergeist scanners. Ben Stephenson of Fillmore monitors swaying drapes in an upstairs window. The Other is out there, he is sure.75

Figure 12.

Pioneers brood in the portrait hall of the Utah Territorial Statehouse, Fillmore. Credit: HWALKER597/Atas Obscura.

Gunnison’s phantom has yet to be documented, but W.W. Drummond, the scoundrel, is part of Fillmore’s statehouse story, for it may have been here that the runaway judge concocted his conspiracy theories. Fifty paces from Drummond’s perch were mud-red walls of the fort where Kanosh faced down an emigrant’s rifle. A Conoco station down I-15 marks the meadow where Toniff died for his arrow. To the west, then as now, was blue translucence, vague and oddly refracted. The Buenaventura had been its grandest deception. Emptiness, another illusion. Death by Danites, a fable that endures to this day. Physically, topographically, the Sevier’s blankness was similar in scrubgrass and sand to 40-some dry lake playas in the Great Basin of Utah-Nevada. Psychologically, nevertheless, it taunted. Hopeless and vast and therefore, perhaps, a blind spot for American scholars, it had been since the time of Miera that gap on the map, that void, just beyond the reach of scientific instrumentation. Amorphous, it intoxicated. Streams disappeared. Sinks appeared to be oceans. Dust appeared to be demons. Floating tremors of atmospheric refraction were easy to translate as horror.

“Far off things [will] mock you”, said Gunnison enroute to mayhem. “As you endeavor to reach them, they sink out of sight”.76

Mocking still, that most baffling of uncanny places, the Sevier glistens again in a Canadian proposal to dredge potassium sulfate.77 Sevier Lake potash at USD 625 a ton is said to be worth USD 7 billion. In 2023, however, the dredges stand idle for lack of investors. Dunes migrate across an access road to Moshoquop’s rebel hideout. Corn Creek to the east diverts to alfalfa. Pahvants, now Southern Paiutes, flank a cinderblock community center above the Kanosh townsite. An obelisk, misdated, marks a random spot in a humble pasture where Kanosh may have been buried. Gunnison decomposes nearby—his thighbone under granite in Fillmore, his skull, never recovered, in the chalk of a vanishing delta in the curse at the core of the crime.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | “INDIAN SYMPATHY—INDIAN TREACHERY”, The Intelligencer, Saint Louis, Missouri, 1 December 1853; see also “Letter to the Editor”, Deseret News (Salt Lake City) in the reprint preface to Gunnison (1860), p. vii. |

| 2 | Gunnison, The Mormons, p. 22. |

| 3 | Hauntings are repetitive grief-stricken responses to fear and alienation in Blanco (2012), pp. 69–99; see also Beck (2001); and Heholt and Downing (2016), pp. 4–16. |

| 4 | Arrington (1951); see also Wilberg (1991), pp. 11–21; for mirages see Gibbs (1909), p. 179. |

| 5 | Volney King, “Twenty-Five Years in Millard County” (typescript), MS 0638, Volney King Papers, 1873–1924, J. Willard Marriott Digital Library, University of Utah, p. 24; see also “The Railroad and the Mormons, 30 October 1869, from Nineteenth Century Newspaper Index, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, https://jstor.org/stable/community.31321828 (accessed on 1 January 2022). |

| 6 | “The Mormon Outrages”, New York Daily Times, 1 May 1857. |

| 7 | “The Murder of Capt. Gunnison”, Liberty Weekly Tribune, May 8, 1857; see also (Drummond 1857). |

| 8 | See Bancroft (1890), p. 470. |

| 9 | Robert Kent Fielding, “Growing Up Mormon” (typescript 1997), p. 5, MSS 7659, Harold B. Lee Library Special Collections, Brigham Young University, Provo, see also Fielding (1992). |

| 10 | William H. Goetzmann saw the killings as an aberration in the otherwise heroic triumph of map-making science in (Goetzmann 1959); see also, Schubert (1980), pp. 99–103. |

| 11 | See (Twain [1872] 1913), p. 127. |

| 12 | Wister (1897), p. 23; see also Francaviglia (2003), p. 8. |

| 13 | See Wilberg (1991), p. 7. |

| 14 | Escalante (1995), p. 76; the standard overview is Bolton (1951); see also Briggs (1976), pp. 113–18; and Kessell (2013), pp. 91–118. |

| 15 | Escalante, The Domínguez-Escalante Journal, p. 76. |

| 16 | See Power (1920), p. 46. |

| 17 | Briggs, Without Noise of Arms, p. 114. |

| 18 | Bolton, Pageant in the Wilderness, p. 71; see also Haymond (1994). |

| 19 | “Gather Pottery and Arrowheads”, Millard County Chronicle, 6 June 1931; see also Briggs, Without Noise of Arms, p. 114. |

| 20 | See Kessel (2017), p. 28. |

| 21 | See Jurgens (1979), p. 26. |

| 22 | Wheat (1957–1962), pp. 2, 83; see also Crampton and Kline (1956), pp. 163–71. |

| 23 | Victor (1870) p. 33; see also Moffat (1980), pp. 8–9. |

| 24 | Frémont (1849), p. 11; see also Morgan (1973), p. 63; and Goetzmann, Army Exploration in the American West, p. 76. |

| 25 | See Frémont (1845), p. 174. |

| 26 | Erwin and Gudde (1958), pp. xxix, 113; see also Wysong (2018), pp. 129–47. |

| 27 | John C. Frémont, “Geographical Memoir upon Upper California”, House Misc. Doc. 5, 1st Sess., 30th Cong. (1848), p. 11. |

| 28 | Frémont, Report of an Exploration, pp. 173, 268. |

| 29 | See (Van Dyke [1901] 1999), p. xxvi; see also Harding (2014), pp. 3–26; and Fox (2000), pp. ix, 3–14. |

| 30 | “America the Most, Superlatively Speaking”, Life Magazine, 1 July 1986, p. 28; see also “Loneliest Road in America”, https//:travelnevada.com/road-trips/loneliest-road-trips/lonliest-road-in-America (accessed on 1 January 2022). |

| 31 | Charles Hillinger, “Life on the ‘Loneliest Road,’” Los Angeles Times, August 25, 1986. |

| 32 | Mace (2012), p. vi; see also Sherin et al. (1996), pp. 155–68; for climate change, see Simms (2008); vol. 66, pp. 233–34; for population estimates see David Rich Lewis, “Native Americans in Utah”, Utah History Encyclopedia, https://www.uen.org/utah_history_encyclopedia/n/NATIVE_AMERICANS.shtml (accessed on 1 January 2022). |

| 33 | Fowler (1969), p. 28; for creation legends see also Reeve (2010), pp. 10–32. |

| 34 | See Campbell (1996), pp. 119, 121. |

| 35 | Talmage (2019), pp. 46–68; see also, Smith (1830), pp. 73, 564. Mathew Bowman explores the dark side of pigmentation in “A Mormon Bigfoot: David Patten’s Cain and the Conception of Evil in LDS Folklore”, in Van Wagenen and Reeve (2011), pp. 27–29, 36. |

| 36 | Gunnison, The Mormons, pp. 13, 153, 165. |

| 37 | Mace, “Where Dry Rivers Meet”, pp. 5–8; see also Simms, Ancient Peoples, pp. 45, 124. |

| 38 | Lyman (2009), pp. 157–207; see also Lewis (2003), pp. 342–57; for skin turning white see Palmer (1928), p. 15; and “Origins of Utah Place Names”, Millard County Chronicle, 8 December 1938. |

| 39 | Statement of Israel Call, 26 August 1908, Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah; see also Anson Call autobiography circa 1856–1889, p. 46 (typescript), MS 313, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. |

| 40 | See Carvalho (1859), pp. 243–44; and Miller (1968), pp. 37–44. |

| 41 | Anson Call autobiography and journal, p. 46. |

| 42 | Earl Spendlove, “Moshoquop’s Terrible Revenge”, The West, April 1967, pp. 10–12, 654–66; see also Lyman and Newell (1999), pp. 67–68. |

| 43 | King, “Twenty-five Years in Millard County”, p. 29. |

| 44 | “Atrocities—Then and Now”, Millard County Chronicle, 10 October 1939; see also Roberts (1913), p. 290. |

| 45 | Twain, Roughing It, pp. 70–71. |

| 46 | Anson Call autobiography and journal, p. 46; see also Mumey (1955), p. 145. |

| 47 | Mumey (1954), pp. 19–32; see also Stansbury (1853), pp. 14, 30. |

| 48 | See Beadle (1873), p. 150. |

| 49 | “Report on the Several Pacific Railroad Explorations”, The North American Review, 82, no. 170 (January 1856), p. 218. |

| 50 | Frederick Creutzfeldt Journal, 1853, Record Unit 7157, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C. |

| 51 | U.S. War Department, “Report of Explorations and Surveys to Ascertain the Most Practical and Economical Route for a Railroad”, Sen. Ex. Doc 78, 33rd Cong., 2nd Sess. (1855), pp. 43–49; see also De Bow (1849), pp. 20–21. |

| 52 | Wimmer (2010), pp. 6–7, 105–8; see also Walker (2002), pp. 25–47; and Brookes (1978), p. 97. |

| 53 | J.W. Gunnison to Martha Gunnison, 18 October 1853, J. W. Gunnison Papers, Huntington Library, San Marino, California. |

| 54 | U.S. War Department, “Report of Explorations and Surveys”, pp. 74, 80–87; see also (Miller 1968), pp. 52–57. |

| 55 | See Walker (1995), pp. 152, 165. |

| 56 | “Testimony of Arwich”, 21 March 1855, New York Times, 18 May 1855; see also “Names of Indians in Gunnison Massacre”, Millard County Chronicle, 5 June 1960; and Knack (2001), pp. 16–17. |

| 57 | Edwin Stott to Andrew Jensen, 26 October 1853, Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; see also Gibbs (1928), pp. 65–75; and Dimick Huntington to Brigham Young, 11 November 1853, excerpted in Mumey, John Williams Gunnison, pp. 117–18; for the bounding heart see Fielding, Unsolicited Chronicler, pp. 259–60, 368. |

| 58 | Missouri Democrat editorial, reprinted with rejoinder in “A Grave Charge”, Deseret News, 3 March 1854. |

| 59 | “The Late Captain Gunnison”, Daily Alta California, 6 May 1855; Horne (1945), p. 111. |

| 60 | Walker, “President Young Writes Jefferson Davis”, p. 168. |

| 61 | Gordon and Shipps (2017), pp. 307–47; see also Turley and Brown (2023), pp. 15–16, 286. |

| 62 | Dutton (1882), p. 154; see also Van Dyke, The Desert, p. 126. |

| 63 | Grove Karl Gilbert, “Reports on exploration in Nevada and Arizona”, Sen. Doc. 65, 42 Cong., 2d Sess. (1872), pp. 90–94 |

| 64 | “Interesting from Utah: Trial of the Indian Murders of Captain Gunnison”, New York Daily Times, 18 May 1855. |

| 65 | “Freaks of Popular Sovereignty”, The Oregon Argus, 30 May 1857. |

| 66 | Poll and Mackinnon (1994), p. 20. |

| 67 | Brooks (1950); see also Walker et al. (2008), pp. 194, 213; and Bagley (2002), pp. 235, 245. For fables deeply embedded see Novak and Rodseth (2006); see also, Garland Hurt to Jacob Forney, 4 December 1857, in “The Utah Expedition”, House Ex. Doc. 71, 35th Cong., 1st sess. (1858), p. 203. |

| 68 | See Gibbs (1910), p. 27. |

| 69 | See Cornwall and Arrington (1983), p. 156. |

| 70 | Givens (1997), pp. 5, 124, 172; see also Richard Alan Nelson. “Commercial Propaganda in the Silent Film: A Case Study of ‘A Mormon Maid’ (1917)”, Film History, 1 (1987): 149–62; for 21st century Mormon bashing see Johnson (2003), pp. 144–46. |

| 71 | Brett Carstens, “Gunnison Massacre Site”, YouTube video, 10:52, 20 January 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlXb4WGz118 (accessed on 1 January 2022). W. Paul Reeve tracks desert hauntings in “‘As Ugly as Evil’ and ‘As Wicked as Hell’: Gadianton Robbers and the Legend Process among the Mormons”, in Wagenen and Reeve, eds., Between Pulpit and Pew, pp. 40–65. |

| 72 | Jessica Blackwell and David D. Spence, “The Stone Tape Theory: Echoes in Time”, PSIresearcher, 19 March 2012, https://psiresearcher.wordpress.com/2012/03/19/the-stone-tape-theory-echoes-in-time/ (accessed on 1 January 2022). |

| 73 | Baucom (2016), p. 93; see also “Cove Fort”, Beaver County News, 30 January 1925; and “Pioneer Day Celebrated”, Millard County Chronicle, 26 June 1928; for Freudian psychosis in memory studies see Trigg (2012), pp. 25–28; see also Dziuban (2014), 111–35, 237 |

| 74 | “An Interview with Raymond Stott”, Millard County Chronicle, 11 December 1930; see also “Delta”, Millard County Progress Review, 3 June 1927. |

| 75 | “Daily Ghost Check—Utah Territorial Statehouse”, Facebook video, 8: 13, 29 August 2021, https://mk-mk.facebook.com/UtahStatehouse/videos/daily-ghost-check/1142462155846788/ (accessed on 1 January 2022); see also “Territorial Statehouse EVP/Spirit Box Session”, YouTube video, 21:10, 20 February 2020, https://www.youtube.comwatch?v=fgc_E4PY6Qg (accessed on 1 January 2022). |

| 76 | See Note 2 above. |

| 77 | Brian Maffly, “Big Utah Potash Project Collapses”, Salt Lake Tribune, 11 October 2020. |

References

- Arrington, Leonard J. 1951. Taming the Turbulent Sevier: A Story of Mormon Conquest. Western Humanities Review 5: 386–406. [Google Scholar]

- Bagley, Will. 2002. Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Mountain Meadows Massacre. Norman: University of Oklahoma, pp. 235, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft, Herbert Howe. 1890. History of Utah. San Francisco: History Company, p. 470. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom, John E. 2016. ’Make It an Indian Massacre’: The Scapegoating of the Southern Paiutes. Master’s thesis, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA; p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- Beadle, John Hanson. 1873. The Undeveloped West. Philadelphia: National Publishing Company, p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, John. 2001. The American Desert as Trope and Terrain. Nepantla 2: 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, María del Pilar. 2012. Ghost-Watching American Modernity. New York: Fordham University Press, pp. 69–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, Herbert E. 1951. Pageant in the Wilderness: The Story of the Escalante Expedition in the Interior Basin, 1776; Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society.

- Briggs, Walter. 1976. Without Noise of Arms: The 1776 Domínguez-Escalante Search for a Route from Santa Fe to Monterey. Flagstaff: Northland Press, pp. 113–18. [Google Scholar]

- Brookes, Juanita, ed. 1978. Not By Bread Alone: The Journal of Martha Spence Haywood; Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, p. 97.

- Brooks, Juanita. 1950. Pioneered Modern LDS Scholarship in The Mountain Meadows Massacre. Stanford: Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Douglas. 1996. ‘White’ or ‘Pure’: Five Vignettes. Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 25: 119, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, Solomon Nunes. 1859. Incidents of Travel and Adventure in the Far West. New York: Derby & Jackson, pp. 243–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, Rebecca Foster, and Leonard J. Arrington. 1983. Perpetuation of a Myth: Mormon Danites in Five Western Novels, 1840–90. Brigham Young University Studies 23: 156. [Google Scholar]

- Crampton, Gregory, and Gloria Griffen Kline. 1956. The San Buenaventura: Mythical River of the West. Pacific Historical Review 25: 163–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bow, J. D. B. 1849. Intercommunication between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. De Bow’s Review 7: 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, William. 1857. Letter to M. D. Gunnison. New York Times. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, Clarence E. 1882. Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District; Washington, DC: U.S. Geological Survey, p. 154.

- Dziuban, Zuzanna. 2014. Memory as Haunting. HAGAR Studies in Culture, Polity and Identities 12: 111–35. [Google Scholar]

- Erwin, G. Gudde, and Elizabeth K. Gudde, eds. 1958. Exploring with Frémont: The Private Diaries of Charles Preuss. Norman: University of Oklahoma, pp. xxix, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Escalante, Silvestre Vélez. 1995. The Domínguez-Escalante Journal. Logan: University of Utah, p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding. 1992. The Unsolicited Chronicler. Brookline: Redwing Book Co. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, Catherine S. 1969. John Wesley Powell and the Anthropology of the Canyon Country; U.S. Geological Survey, Professional Papers, 670; Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 28.

- Fox, William L. 2000. The Void, the Grid & the Sign. Reno: University of Nevada Press, pp. ix, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Francaviglia, Richard V. 2003. Believing in Place: A Spiritual Geography of the Great Basin. Reno: University of Nevada Press, p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Frémont, John C. 1845. Report of an Exploration of the Country Lying Between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains. Washington, DC: Gales and Seaton, p. 174. [Google Scholar]

- Frémont, John Charles. 1849. Geographical Memoir upon Upper California. Washington, DC: Tippin & Streeper, p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, Josiah F. 1909. The Lights and Shadows of Mormonism. Salt Lake City: Salt Lake Tribune Publishing Co., p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, Josiah F. 1910. The Mountain Meadows Massacre. Salt Lake City: Salt Lake Tribune Publishing, p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, Josiah F. 1928. Gunnison Massacre—1853—Millard County—Indian Mareer’s Version of the Tragedy—1894. Utah Historical Quarterly 1: 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givens, Terryl L. 1997. The Viper on the Hearth: Mormons, Myths, and the Construction of Heresy. Oxford: Oxford University, pp. 5, 124, 172. [Google Scholar]

- Goetzman, William H. 1959. Army Exploration in the American West, 1803–1863. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 283–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Sarah Barringer, and Jan Shipps. 2017. Compare Methodist and Mormon doctrines of blood atonement in “Fatal Convergence in the Kingdom of God. Journal of the Early Republic 37: 307–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnison, John Williams. 1860. The Mormons, or Latter-Day Saints. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., p. vii. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Wendy. 2014. The Myth of Emptiness and the New American Literature of Place. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Haymond, Jay M. 1994. Sevier Lake. In Utah History Encyclopedia. Salt Lake City: Utah Educational Network. Available online: https://www.uen.org/utah_history_encyclopedia/s/SEVIER_LAKE.shtml (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Heholt, Ruth, and Niamh Downing, eds. 2016. Haunted Landscapes: Super-Nature and the Environment. London: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, Flora Diana Bean, ed. 1945. Autobiography of George Washington Bean, a Utah Pioneer. Salt Lake City: Utah Printing Company, p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Janiece. 2003. Convicting the Mormons: The Mountain Meadows Massacre in American Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, pp. 144–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens, William A. 1979. The Faith of the Early Fathers. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, vol. 3, p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Kessell, John L. 2013. Miera Y Pacheco: A Renaissance Spaniard in Eighteenth-Century New Mexico. Norman: University of Oklahoma, pp. 91–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kessell, John L. 2017. Whither the Waters: Mapping the Great Basin from Bernardo del Miera to John C. Frémont. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Knack, Martha C. 2001. Boundaries Between: The Southern Paiutes, 1775–1995. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska, pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Hyrum S. 2003. Kanosh and Ute Identity in Territorial Utah. Utah Historical Quarterly 71: 342–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyman, Edward Leo. 2009. Chief Kanosh: Champion of Peace and Forbearance. Journal of Mormon History 35: 157–207. [Google Scholar]

- Lyman, Edward Leo, and Linda King Newell. 1999. A History of Millard County; Salt Lake City: Utah Historical Society, pp. 67–68.

- Mace, Dylan J. 2012. Where Dry Rivers Meet: A Palimpsest of the Pahvant Valley, Black Rock and Sevier Deserts. Master’s thesis, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA; p. vi. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, David Henry. 1968. The Impact of the Gunnison Massacre on Mormon-Federal Relations: Colonel Edward Jenner Steptoe’s Command in Utah Territory, 1854–1855. Master’s thesis, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA; pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, Riley Moore. 1980. Printed Maps of Utah to 1900: An Annotated Cartobibliography. Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA; pp. 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Dale L. 1973. The Great Salt Lake. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- Mumey, Nolie. 1954. John Williams Gunnison: Centenary of His Survey and Tragic Death. Colorado Magazine 31: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mumey, Nolie. 1955. John Williams Gunnison (1812–1853): The Last of the Western Explorers. Denver: Artcraft Press, p. 145. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, Shannon A., and Lars Rodseth. 2006. Remembering Mountain Meadows: Collective Violence and the Manipulation of Social Boundaries. Journal of Anthropological Research 62: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, Wm. R. 1928. Indian Names in Utah Geography. Utah Historical Quarterly 1: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poll, Richard D., and William P. Mackinnon. 1994. Causes of the Utah War Reconsidered. Journal of Mormon History 20: 20. [Google Scholar]

- Power, Jesse Hazel. 1920. The Domínguez-Escalante Expedition into the Great Basin, 1776–1777. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, W. Paul. 2010. Making Space on the Western Frontier: Mormons, Miners, and Southern Paiutes. Champagne: University of Illinois Press, pp. 10–32. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Brigham H. 1913. History of the Mormon Church. Americana 8: 290. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, Frank N. 1980. Vanguard of Expansion: Army Engineers in the Trans-Mississippi West, 1819–1879. Washington, DC: History Division, Office of the Chief of Engineers, pp. 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sherin, Nancy, Carol Loveland, Ryan Parr, and Dorothy Sak. 1996. A Late Archaic Burial. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 18: 155–68. [Google Scholar]

- Simms, Steven R. 2008. Ancient Peoples of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau. London: Routledge, vol. 66, pp. 233–34. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Joseph. 1830. Book of Mormon. Palmyra: E.B. Grandin, pp. 73, 564. [Google Scholar]

- Stansbury, Howard. 1853. Exploration and Survey of the Valley of the Great Salt Lake of Utah; Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, pp. 14, 30.

- Talmage, Jeremy. 2019. Black, White, and Red All Over: Skin Color in the Book of Mormon. Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 28: 46–68. [Google Scholar]

- Trigg, Dylan. 2012. The Memory of Place: A Phenomenology of the Uncanny. Columbus: Ohio University Press, pp. 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Turley, Richard E., and Barbara Jones Brown. 2023. Vengeance is Mine: The Mountain Meadows Massacre and Its Aftermath. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 15–16, 286. [Google Scholar]

- Twain, Mark. 1913. Roughing It. New York: Harpers & Brothers, p. 127. First published in 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke, John C. 1999. The Desert: Further Studies in Natural Appearances. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. xxvi. First published in 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagenen, Michael Scott, and W. Paul Reeve, eds. 2011. Between Pulpit and Pew: The Supernatural World in Mormon History and Folklore. Logan: Utah State University Press, pp. 27–29, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, Frances Fuller. 1870. The River of the West: Life and Adventure in the Rocky Mountains and Oregon. Toledo: Columbian Book Company, p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Ronald W. 1995. President Young Writes Jefferson Davis about the Gunnison Massacre Affair. BYU Studies Quarterly 35: 152, 165. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Ronald W. 2002. Wakara Meets the Mormons, 1848–52: A Case Study in Native American Accommodation. Utah Historical Quarterly 70: 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Ronald W., Richard E. Turley Jr., and Glen M. Leonard. 2008. Massacre at Mountain Meadows: An American Tragedy. New York: Oxford University, pp. 194, 213. [Google Scholar]

- Wheat, Carl Irving. 1957–1962. Mapping the Transmississippi West. 5 vols, San Francisco: Institute for Historical Cartography, p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Wilberg, Dale. 1991. Hydrologic Reconnaissance of the Sevier Lake Area, West-Central Utah. Technical Publication 96. Salt Lake City: Utah Department of Natural Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer, Ryan Elwood. 2010. The Walker War Reconsidered. Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA; pp. 6–7, 105–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wister, Owen. 1897. Lin McLean. New York: Harpers & Brothers, p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Wysong, Sheri. 2018. The Mountain Men, the Cartographers, and the Lakes. Utah Historical Quarterly 86: 129–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).