1. Introduction

Purpose of the paper. Our foremost goal is to offer a concise, non-specialist coverage of economic growth and its contribution to transforming the world. How better to tell its story than through the lens of the world’s first growing economy?

In this second paper in a series of four, we establish that economic growth is a two-sided coin. Introducing the pain to growth’s pleasure: economic crisis. This paper surveys the literature to provide a concise journey through the UK’s past experiences of economic crisis, from the mid-1800s to the 2008 Financial Crisis, in a manner accessible to those with or without a background in Economics.

We consider policy decisions, effects on growth and changes to industry and work brought about by historical crises and economic restructuring, and address how crises have altered the UK’s position in the global economy. The past permeates the present—we live in times sculpted by historical decisions. Hence, this paper aims to provide readers with historical context of crisis in the UK, which may be useful when viewing potential effects of current, and future, crises and policy.

In the first half of the paper, we journey through the Second Phase of the Industrial Revolution and into the 20th century, to introduce a potted history of the UK’s economic woes up until the Second World War. We investigate the UK’s first struggles with international economic fragility, when, after the glory days of rapid industrialisation and soaring national wealth, risky investments, trade channels, and interconnected financial markets spelled trouble for UK growth.

We discuss the economic decisions during the First World War that forced the UK government to re-evaluate the policies and political ideologies of unregulated markets and free trade, which had prospered during the Industrial Revolution. We then discover the new economic order that was set in motion by the First World War. The aftermath of the War left the UK economy wheezing, whilst the interwar years, marred by continued economic turbulence, saw the economy undergo significant structural changes, particularly to policy and employment.

The second half of this paper dissects the permanent restructuring effects of three major economic crises with varying triggers: the economic fallout of the Second World War, the 1980–1981 Recession, and the 2008 Financial Crisis. The UK experienced several recessions in the post-war era—not all are covered in this paper. Some recessions are quickly recoverable—the 1956 and 1961 UK recessions only lasted for two quarters each—but often, recessions signal underlying indicators of an unhealthy economic environment. We have selected three periods of economic distress, as these had permanent restructuring effects on the UK economy, employment, society and growth. We consider international power dynamics, domestic policy and productivity, to assess how the pursuit of growth in times of crisis can reconfigure a nation with lasting effects.

We survey the post-Second World War period to investigate trade-offs and compromises faced by policy in times of extreme economic distress, tensions between the comfort of the past and the unknowns of the future, and by considering the Bretton Woods Agreement, we survey the role of international power dynamics in determining a nation’s economic direction.

Through examining the 1980–1981 Recession, we examine the role of political ideology in deciding the industrial structure of the economy, and in influencing the public’s behaviour and perceptions of citizenship and society. Finally, a study of the 2008 Financial Crisis investigates lingering slowdowns in productivity and growth, considers the socio-economic consequences of austerity and covers a major outcome of the crisis: reformed financial regulation.

We currently live in times of immense economic upheaval, resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, conflict and a world economy undergoing great change due to processes such as climate change and new technologies. Uncertain times provoke questions. Are our current experiences new, or reminiscent of history? How may we be able to learn from our past? How might we approach future challenges? People may wish to look to history when seeking answers. The paper does not aim to present comprehensive answers to these questions—it is by no means exhaustive in terms of detail—but it may provide information as a starting point for those wishing to consider the current economy in context of its past.

Finally, we have to stress that the term economic growth is used synonymously with economic development. The reader should not commit the fallacy of equating economic growth solely with increases in GDP. Economic growth encompasses institutions, human capital, technological change, demographics, and much more. The economic theory through which we interpret past events in the present paper is the prevalent, neoclassical view—although, as the reader will notice, this does not lead to controversy in our survey.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 considers the latter half of the Industrial Revolution and presents the economy of the First World War.

Section 3 investigates some of the restructuring effects of the interwar years.

Section 4 and

Section 5 address the economy following the Second World War, including the Bretton Woods Agreement.

Section 6 investigates the 1980–1981 Recession.

Section 7 examines the 2008 Financial Crisis.

Section 8 concludes.

Section 9 is a ’technical zone’ for readers who are interested in the macroeconomic mechanisms behind some of the discussed terminology. References, including those for definitions in the ‘technical zone’, are collected at the end of the paper.

2. Laissez-Faire to Despair

2.1. The Long Depression

Industrialisation had brought the British economy unprecedented wealth. From the mid-19th to early 20th century, the Second Phase of the Industrial Revolution took hold, characterised by widespread usage of steam engines, specialisation of employment into skilled work and the contagion of industrialisation. With it, the advent of a connected global economy meant potential crises were always just around the corner. The first major globally-interconnected economic crisis came in 1873.

At this time, the new British middle class, who had a penchant for speculating stocks, ran the nation through industrial private investment; political sway had reduced since the First Phase of the Industrial Revolution. Productivity was booming, creating a vast labour surplus in rural areas, heightening the structural transition to urban employment, with rapid urbanisation pushing down industrial wages. European production was becoming more integrated and outsourcing British production to reduce costs, particularly labour, was on the rise. In the age of transport, the investments of the new middle class included the development of railways in Britain and the US.

When the US railroad suffered overexpansion, triggering bank runs and a stock market crash in the US, the US experienced the Panic of 1873. At this time, the Suez Canal project failed—the project had attracted hefty sums of British capital to complete and the value of the wealthy elite’s investments plummeted. The crisis hit the US and Europe hard across the population; however, the surface impact in Britain was primarily felt by the middle classes. The impact of devalued investments stifled investment into future developments in British infrastructure.

Continuing deflation led to a reluctance to invest now, knowing that prices will be lower the next day, resulting in a more than 20-year spiral of falling prices and wages which ended in 1896. Given productivity maintained aggregate output, the British economy stagnated, whilst international dominance declined with the emergence of newly-industrialised competition. The period has since been termed ‘The Long Depression’; it marked the beginning of a tough relationship between British economic growth and recurrent economic crisis.

2.2. British Economic Crisis in WWI

The First World War marked a reversal of Britain’s economic fortunes experienced during the previous two centuries. Britain incurred vast economic and human costs, both direct and indirect. The first two years of the war were a mangled concoction of demand shocks and supply shortages. The latter half of the war was characterised by direct economic management, but a deteriorating financial position.

Over the course of the war, Britain incurred vast national debt and had extinguished many of its sources of cash revenues from foreign investment. Its position as the centre of the free-market world had dwindled, and the necessity to focus on economic policy and the role of the state in economic recovery had shifted centuries of focusing on private industry for national wealth. Christopher Phillips notes that government spending contributed 38.7% of British GDP, in comparison to 8.1% preceding the war.

The First World War was a significant turning point in Britain’s experience of economic growth. It ended the glory years of the Industrial Revolution, and through its impact on government, policy and Britain’s macroeconomic conditions, it set Britain on a course that would prove irreversible and define Britain’s prospects for growth, and international position, throughout the 20th century.

Before the war began, the 1914 financial crisis, triggered by murmurs of war in Europe, led to public bank runs to acquire gold. There was reluctance to relinquish gold in the financial sector due to fears of low gold reserves at the Bank of England. Trade and exchange markets froze, the ladder of financial and credit institutions, all contingent on each other, began to strain and could topple. This led to sudden internal demand by financial institutions for money from international debtors. It was not forthcoming due to risks associated with shipping gold on the eve of war.

The British government declared a 5-day bank holiday to halt the economy and give time to devise a plan to prevent the British economy from collapsing. As a result, Britain entered the First World War funded by short-term Treasury Bills (short-term debt) and Ways and Means Advances (designed to bridge temporary shortfalls in cash to cover outlay) under the belief that the war would be a short affair.

Economically, the war can be viewed as two stages: the first led by Prime Minister Asquith from 1914 to December 1916, and the second led by Prime Minister Lloyd George from December 1916 to Armistice Day 1918. The first two years of the war constituted confused economic choices and lack of directional leadership. Britain’s government was torn between calls for state intervention to coordinate the war effort, and maintaining the free-market economy and British financial international superiority.

During this period, there was failure to adopt coherent economic strategies to adequately confront the conflict—the government was reluctant to encroach on the free-market but realised the necessity to strategise the war effort. It requisitioned the railways and textile contracts, but not the control over manpower, meaning by mid-1915, large portions of workers in industries necessary for the war effort had voluntarily enlisted, leading to critical shortages on the frontline. The second half of the war saw conscription of employees from services, finance and commerce in order to maintain levels of production in British industry on home soil.

The tide began to turn with a change of prime minister in December 1916, a month after the Battle of the Somme. Lloyd George established direct economic management, founding new ministries to control different aspects necessary to supply the war, and replacing political decision-makers with business representatives accustomed to coordinating complex supply chains.

Complete state control of the economy turned the war around—Phillips highlights that in the production of munitions, 500,000 shells were produced in the first 5 months of the war but after the change of approach, 50 million shells a year were produced by 1917. British industrial production was soaring and economic growth was robust, with GDP estimated to have risen 14% from 1914 to 1918.

However, the substitution of workers in the first phase meant industrial workers returned to find their jobs replaced by unskilled workers from other sectors or previously unemployed women. As such, fear of labour dilution and industrialists reducing pay to increase profits, led to a surge in union membership, growing from 22% to 44% of the workforce during the war, leading to frequent strikes over pay.

Mechanisation of agriculture during the Industrial Revolution and increases in imports meant Britain was short on agricultural workers and food at the onset of war. In the free-market economy of the early phase of the war, the government was reluctant to regulate the food markets.

By early 1917, skilled agricultural workers were recalled from war, children were taken out of school in favour of agricultural work, and returning servicemen unfit to return to active service, and prisoners of war, were sent to work on farms. Non-farm land was utilised for arable crops and rationing was introduced in 1918. As a result, Britain’s agricultural output climbed during the latter half of the war.

2.3. Debt Galore

Despite the shift in strategy in the second phase, the war was financially difficult. Britain jumped from one funding source to another, burning through cash in reluctance to take on foreign debt and reduce Britain’s post-war financial superiority. An initial plan to fund the war with taxation fell short of the required cash flows to fund expenditures—it is estimated that wartime expenditures were 26% funded by taxation.

Even under Asquith’s government, the emphasis on the free-market was already diminishing through necessity, with free movement of goods reduced through import duties and excess profits tax to impede profiteering by private business. Borrowing constituted the majority share of war financing; with long-term borrowing supplanted in spring 1917, the government adopted a continuous borrowing strategy, amalgamating a series of short-term debt sources of funding.

As a result, management of the debt became administratively time-consuming, while diminishing cash and foreign investments meant the debt was increasingly unbacked by liquidity. Demand for Dollars to support trade with the US led the government to seize Dollar-denominated securities held by British private investors to be sold in the US; however, the resulting cash was quickly exhausted.

By the end of the war, Britain had been forced to take on levels of debt estimated at 130% of its GDP, stifling the economy, which before the war had only debt to the value of 25% of GDP on its books. Economic growth was reduced through high interest rates and high taxes, hence reduced investment and a reduction in total factor productivity due to lack of technological development.

Loans that Britain had made to allies, hoping to recoup gold reserves through repayment—mainly France and Russia—were looking unlikely to be settled, whilst Britain had borrowed from the US, who were keen for prompt repayment. The most significant British policy decision following the war was the decision to return to the gold standard to prevent rising interest rates. Returning to the gold standard meant drastic deflation in the early 1920s, plunging the economy into a deep recession, causing a permanent increase in the rate of unemployment (average unemployment rate for all workers in 1921–1922 was 11.5%).

Nicholas Crafts highlights that this deflationary adjustment meant real earnings showed no growth in the years 1919–1926. Dramatically falling prices and the large ‘differential between real interest rates and real growth rates’ caused the real value of Britain’s war debt relative to GDP to rise.

The real value expresses the quantity of goods equivalent to the monetary value of the debt, hence lower prices meant GBP 1 had purchasing power over more goods. As the real value of the debt rose, it became increasingly difficult to clear the debt balance—in 1923 the public debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 1.76 (compared to 1.3 immediately after the war). Overall, reduced production once the war effort subsided, a surplus of labour once troops were demobilised and deflationary economic policy led to a rise in the unemployment rate, which reduced the annual real GDP.

A reduced trade-to-GDP ratio—trade-to-GDP indicates the relative importance of international trade to the nation—meant the national cash inflows from international trade were reduced throughout the 1920s. The debt-to-GDP level grew from its pre-war levels, reducing economic growth hence reducing the annual levels of GDP year-on-year. In total, the macroeconomic effects of the First World War all pointed to reductions in GDP throughout the 1920s.

By the end of the Second Phase of the Industrial Revolution, Britain’s economy was heavily reliant on import-export trade. Trade constituted a higher portion of Britain’s GDP than its industrial and industrialising counterparts. Import disruptions during the war prevented Britain acquiring necessary supplies for manufacturing needed for the war effort. However, the true cost to the British economy was the long-term impact of loss of the trade advantage.

Before the war, Britain’s economic prowess was gaining rivals due to recent industrialisation in the US and Europe. The British economy’s struggle with the after-effects of the First World War only enhanced the global catch up to Britain’s previous economic strength, and reduced Britain’s status in the global economy.

The war prevented the import-export contribution to British GDP from continuing at its pre-war levels and other nations, primarily the US and Japan benefited, replacing portions of British exports in key regions such as India. Britain had attempted to maintain its economic position whilst concurrently trying to win the world’s first major mechanised conflict.

Its biggest fear was surrendering its international financial centre—the City of London—to the US. By adopting this mindset, Britain finished the war both cashless and entrenched in debt. The era of British reliance on the purely free-market system was over. Crafts argues that the loss of GDP as a result of WW1 over the course of the 1920s approximately ‘doubled the total costs of the war to Britain’.

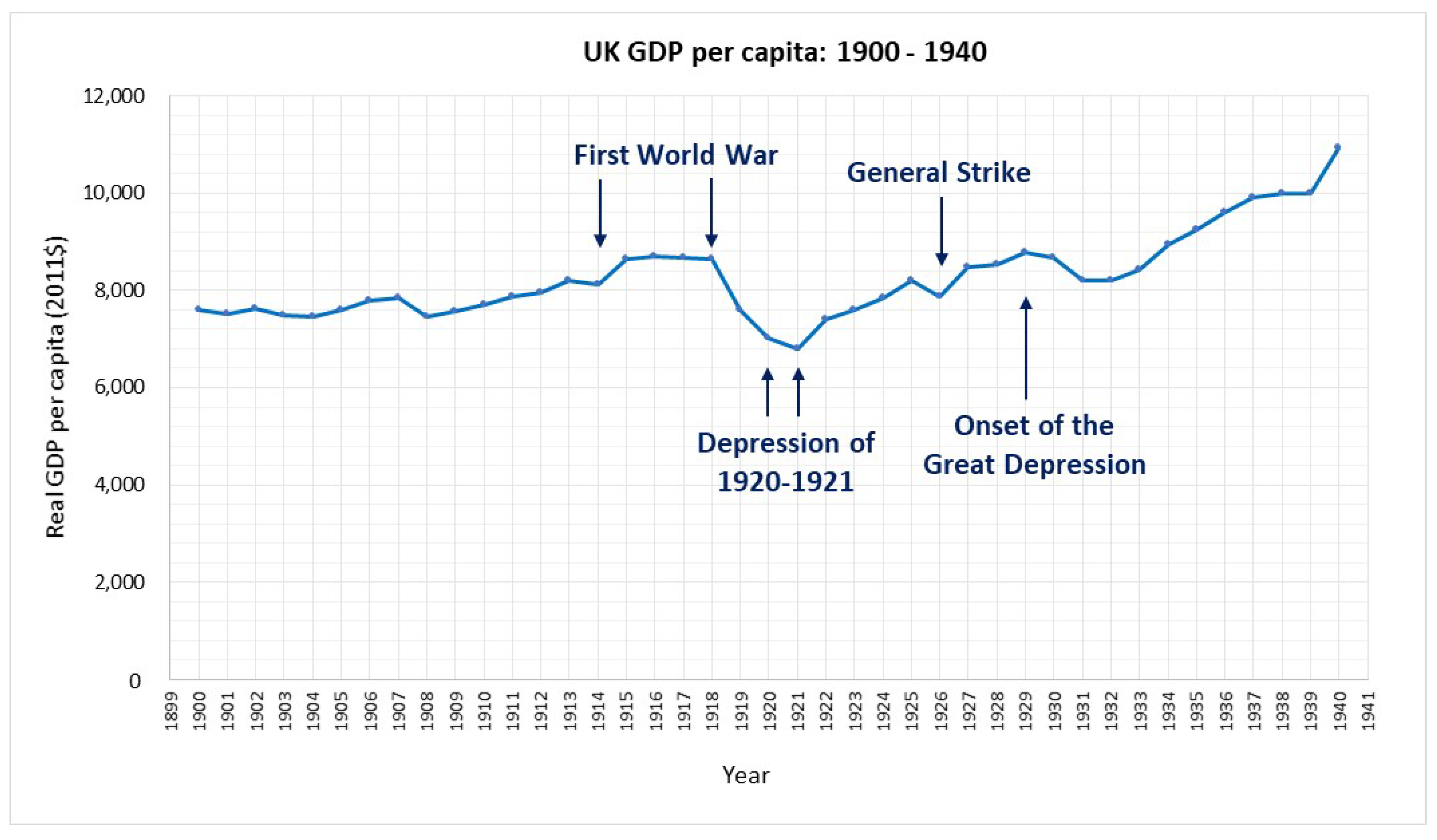

The global economic fallout from the First World War is viewed as a key driving force of the Great Depression in 1929. After a centuries-long soar of sustained economic growth, the depression of 1920–1921 brought the first significant drop in British GDP per capita since sustained growth began around 1650. The drop in growth took the wind out of the sails of the British economy, causing a 21.95% drop from the peak GDP per capita on record in 1916 to the hit in 1921 (calculated using Maddison Project Data at 2011 prices).

The hit took the British economy back to the GDP per capita levels of the mid-1890s and it took until 1929 to regain 1916 GDP per capita levels. Growth in the years immediately after the war acted to re-establish Britain’s pre-war economic position, only to be thrown backwards again by the impacts of the Great Depression. GDP fell again, dipping in 1931–1932, back to 1914 levels. Industrial areas of Britain were particularly impacted, with British exports halving, sending unemployment rates to around 20%. It was not until 1934 that GDP per capita exceeded 1916’s all-time peak and regained its ascent of continuing economic growth.

Figure 1 shows the development of GDP per capital in Britain during these periods.

3. Interwar Shifts

The interwar years presented significant challenges to the maintenance of British economic growth. The post-war challenges presented difficult macroeconomic conditions for increasing output, whilst international economic turbulence festered throughout the period. The British economy never fully returned to its complete embrace of the frictionless free trade that had characterised the pre-war period, enacting protectionist policies to protect British industry amidst a declining global market share.

Protectionist policies were successful in regaining British growth; however, the interwar years set in motion long-run trends in employment and drivers of growth, impacting productivity, hence future growth, even after the Second World War. The interwar period was defined by unemployment, changing structures in private business and the changing face of industry. Throughout the period, disjoint in labour relations exacerbated high tensions due to unemployment and demand declines for British goods. This economically crisis-stricken era laid the foundation for a plethora of societal disquiet that persisted throughout the 20th century.

3.1. Protectionism

British economic policy in the interwar period emphasised protectionism, attempting to defend British production and strengthen ties with the ‘Imperial Bloc’ through trade, where a trading advantage had been diminished during the First World War. Pre-WW1 the British economy was fanatical about free trade amidst an increasingly globalised economy; attempts from the Conservatives to reform tariffs to favour an ‘Imperial Bloc’, wanting to strengthen British power against rising trade rivals, were quashed in favour of sustaining tariff-free unilateral free-trade.

The direct economic management of the First World War heavily influenced the post-war economic landscape. The government was reluctant to return to the ‘laissez-faire’ economics, which had contributed to the turmoil of early efforts in the First World War.

During the economic fallout from the First World War, international trade lost its multilateral nature and the UK became insular in its trading policies, backing discriminatory trade policies to complement its protection of British production. The UK explicitly favoured Empire nations over free trade with globalised economies such as Europe and the US.

The post-WW1 period saw the UK increasingly stringent on the quantities and types of goods which could be freely imported, with increasing commodity-specific tariffs, embargoes (such as the 1926 pork embargo prohibiting pork imports from Europe) and Acts to safeguard British industry. The Empire was already favoured in the period up to major reforms in 1930, with lower import duties on goods imported from the Empire and exemptions from duties on key goods in the 1921 duties.

The Great Depression led the British government to tighten restrictions on foreign imports—a series of Acts throughout the 1930s strengthened the UK position of domestic preference in supply to the British markets and Imperial Preference in imports. The 1931 ‘Abnormal Importations Act’ introduced sweeping tariffs and ad valorem taxes on goods produced outside of the Empire. In 1932, the Ottawa Conference brought together representatives from across the British Empire and stronger bilateral trade agreements were agreed to enhance ‘Imperial Preference’ for manufactured commodities and raw materials.

Political agreements extended beyond that evidenced in tariffs—the turn inward was boosted by active political will towards favouring Empire imports over ‘foreign’ imports. Although falling incomes due to the economic effects of the Great Depression are responsible for the majority of import decline, protectionist policies are estimated to account for approximately one quarter of the decline in imports the UK experienced in the period 1929–1933. Economic historians estimate that over 70% of the switch to Empire imports in 1930–1933 can be accredited to protectionist policy, whilst 50% of the shift can still be attributed to this policy as late as 1938.

Several economic historians view the turn to protectionism as ‘paradoxical’—Britain tightened its grip on controlling its place in the market to protect a global dominance which was already fading. However, data evidences a positive impact of the ‘1932 General Tariff’ (imposed a 10% tariff on British imports, with exemptions for some imports from the Empire) on the industries it protected. The 1932 tariff is attributed as a significant contributory factor to positive GDP growth from 1932 onwards. Industry-specific tariffs increased domestic productivity, improving output in protected sectors and encouraging substitution to British goods in the domestic market.

Given the economic environment at the time the tariff was enacted, protectionist policies of this kind were beneficial to increasing British industrial productivity and reigniting the trend of economic growth in the UK economy. This contradicts many perspectives amongst economic theorists that protectionism is detrimental to growth. As such, these policies demonstrated that contextual economic conditions are a significant factor for a policy’s success.

3.2. Corporate Structure and the Private Sector

The interwar period began to restructure British employment as the shape of the private sector altered. This era saw the idea of the ‘corporate manager’ in its infancy. Although ‘merger waves’—where companies were combined to create larger and more powerful entities—had been prevalent during the final years of the 1800s, failure to understand the limits to managerial capacity of the sudden surge in growth led companies to re-divide or collapse.

In the interwar period, technological innovations, however, such as accounting machines and the increasing prominence of the telephone, and new methods in accountancy, costing methodology and budgeting techniques, led firms to understand their financial position and market power potential. Some large-scale companies began to form, giving rise to the private sector professional, such as accountants and business administrators.

Further, the private ‘trading estate’—an area of land developed by private industry, primarily for manufacturing—became a pivotal part of employment. New fields of work emerged in ‘new industries’ such as the expansion of electrical engineering and the new focus on consumer goods such as cars. With these changes, the face of British employment shifted, altering the drivers of British economic growth.

The changing private sector created institutional change—firms formed as hierarchical institutions, akin to central and local government and public systems. In some areas, private owners of trading estates funded local amenities and services, acting in the role of the state. Over time, the government began to structure itself to serve the employment needs of these private companies, directing the Ministry of Labour and Labour Exchanges towards offering jobs in manufacturing sectors on behalf of the employers.

The formation of corporate structure attempted to provide the private sector with longevity, by a business becoming an entity of itself (e.g., from Lord Leverhulme’s estate to Unilever), and by planning for future economic performance. Although large-scale mergers were still infrequent, by 1939 there were 61 British companies with a market capitalisation of over GBP 8 million (over a 2-fold increase from 1924, and nearly a 9-fold increase on the 1907 number).

The early stages of the modern structure of the divisional, decentralised corporate firm were developing and proving successful in some companies, such as Imperial Chemical Industries (I.C.I.), by the end of the interwar period, reducing competition in the private sector. I.C.I. had successfully acquired other firms by managing its long-term growth through staggered acquisitions over several years, so could decide which companies were absorbable without financially distressing the existing firm.

Although the foundations and strategy necessary to manage large-scale business were emerging, many companies failed to adopt it due to reluctance to acknowledge the power of trained management and strategised business operations, along with a resistance to rationalisation.

Aversion to the large-scale corporate firm would later impact Britain’s productivity, severely impacting the economy’s ability to generate the level of growth achieved by international counterparts.

3.3. Workforce and Productivity

3.3.1. Unemployment

Many political and economic commentators have sought to explain the drastic unemployment figures of the interwar period, which hovered regularly in double-figures from 1921 to 1938 (averaging 14% and never falling below 9.5%).

Some commentators and analysts have offered theories of ‘voluntary unemployment’ due to generous state unemployment insurance through the National Insurance scheme, suggesting that receiving benefits surpassed net earnings from employment for lower earners. However, others question whether a large portion of unemployment was voluntary, with difficulty finding empirical evidence to ascertain causality between unemployment and benefits, due to intricacies regarding eligibility. Some query whether, at such high national unemployment rates and destitution, discussions about whether unemployment benefits or paid employment were most financially beneficial were unlikely to have been central to employment choice.

The Keynesian school of thought argued that low expenditure decreasing aggregate demand contributed to high involuntary unemployment, advocating for government spending to refloat the economy. Whichever perspective prevails, high unemployment presented a significant source of inefficiency in the economy and reduced output. Idle human capital, in combination with declines in production output due to reduced demand in the market, meant prospects for growth suffered during the 1920s and early 1930s.

3.3.2. Human Capital

Adjustments in the structure of the private sector meant the traditional ‘word-of-mouth’ manner to gain employment was coming to its end, representing a significant overhaul in the nature of employment. Private firms began to develop recruitment strategies and also recruited from the government for personnel skilled in specific administrative tasks. The development of internal recruitment structures and the National Insurance Scheme formalised work.

The need to contribute to National Insurance to receive unemployment benefits meant the workplace became an all-in or all-out environment, restricting casual or temporary work which in previous eras had enabled many women to work. The interwar period has been identified as forming ‘the housewife ideology’, as to undertake temporary duties at home, women may have needed to become permanently unemployed. Further, changes in property purchase and rental reduced housing availability for unmarried women, making it difficult to live near workplaces—this catch-22 situation could bar women’s participation in the workforce, hence from individual access to the economy.

The rising influence of the ‘Fordist’ system of corporate recruitment i.e., recruitment only of the ‘typical family man’ excluded many from the workforce. Reducing opportunity for work and selective employment practices creates efficiency losses in the economy by incurring wasted human capital due to able workers left unemployed, hence productivity is sub-optimal and growth potential is not fully utilised.

Reduced aggregate demand for industrial goods, led to high unemployment in heavy industries. The government sought to rid the unemployment problem through Labour Exchanges formed by the Ministry of Labour. This included moving young men from former industrial ‘distressed’ areas into boarding facilities where they were offered employment in local ‘new’ industries at a lower rate of pay than locals, or offering young men work in ‘work camps’ (later renamed ‘instructional centres’) to train them in manual labour.

Refusing to attend the work camp (‘accept the job from the Exchange’) resulted in withdrawal of unemployment benefits. However, training workers in generic manual labour did not provide workers in distressed areas with the precise skillsets necessary to gain employment in new sectors which were key drivers of growth. Hence workforce adaptability was reduced, making communities vulnerable to employment diversification away from heavy industries and manual labour.

A change in geographical distribution of industry during this period (with trading estates mostly established in the south of England) contributed to the fall of industrial heartlands, such as South Wales and the North East of England where workers were forced out of heavy industry areas into ‘new’ industries. Thereby creating pockets of prosperity, without rebuilding declining areas, which impaired future growth potential on a national scale.

3.3.3. Rigidities

The surge in industrial representation during the First World War led to prominent strikes in the 1920s against reduced wages and increasing work hours as a result of the rising costs of British exports (due to the decision to link British currency to the gold standard). However, the dominance of trade unions drastically declined in the post-war era. Bargaining power and the effectiveness of industrial strike action waned during periods of mass unemployment and decline in markets for industrial goods.

Collectives that still existed, however, displayed ‘institutional rigidities’—the failure of trade unions and particularly employers’ organisations to adapt to the difficult economic environment of the deep depression. This was restrictive for interwar British economic development. Organised collective bargaining was continually eroded, whilst some managers struggled, or refused, to adapt to new economic conditions.

Productivity across traditional industries in this era was poor, although employment in these sectors was still relatively high. Although the lessons from the First World War dictated that reliance on pre-existing systems was doomed to fall behind fast shifts in global economic conditions, heavy industry dropped behind in interwar Britain due to insufficient technological innovation (investing in capacity instead of technologies) and deteriorating employer-employee relations.

As a result, heavy industry, previously the jewel in the crown of British economic growth, struggled to maintain competitiveness in a global market. During the interwar period, the engineering workforce altered from 60% skilled and 20% semiskilled in 1914 to 33% skilled and over 50% semiskilled by 1939, deskilling industrial employment, representing a shift from the skills focus of the latter half of the Industrial Revolution and forging a distinct ‘different-ness’ in the British political psyche between the skills (therefore ‘deserved’ wages) of the lower earners and higher earners and managers in industry.

Deskilling reduces human capital accumulation needed to improve productivity in industry, which can reduce future growth potential. Further, a rise in piecework created short-term gains in productivity and income growth, masking underlying inadequacies needing to be rectified to secure long-term growth potential.

3.3.4. Socio-Cultural Restructuring

With the transition to a new form of internal firm structure, private sector employment began to create administrative jobs, forming new roles for ‘workers’, previously only able to work ‘at the coal face’ of industry—this gives ‘employment’ a new definition in the sense of the nature of ‘work’ in the UK economy but also creates a division within ‘workers’ and a new hierarchy of employment.

‘New’ industries were badly unionised due to lack of established workplace collectives, whilst traditional means of union recruitment were significantly reduced as unions could not occupy the private land on which companies had established their ‘trading estates’. These factors are not only significant for understanding the changing drivers of economic growth and industrial production in the British economy, but are relevant to assess future class and societal conflicts that arose during future economic crises. The interwar era not only strengthened class divide and sowed the seeds of employment polarisation, but sought to erode working culture established in industrial communities.

3.3.5. Searching for the New Normal

In the remainder of this paper, we will survey three crises that have been pivotal in structuring the modern-day British economy. The three crises had varying triggers—an international conflict, a domestic policy response to global macroeconomic instability and financial collapse in a globalised economy—but displayed similarities in their effects and subsequent impacts on productivity.

We will review the causes of these crises and the circumstances surrounding the recovery of growth. Primarily, we will assess the restructuring effects of these crises, emphasising changes to industry, productivity and employment. We will observe that responses to temporary crises have long-term implications for economic growth, socio-economic structure, cultural identity and the economy’s ability to absorb the effects of future crises.

4. The Post-WW2 Crisis

The sudden end to the war in Japan in July 1945 forced the UK into its post-war period prematurely. The war was expected to last a further 18 months to 2 years. As such, the abrupt end meant economic strategy was not prepared to begin recovery in such dire economic conditions. At the end of the war, the UK was penniless and heavily indebted. This section draws on references

Broadberry and Crafts (

1996);

Calomiris and Gorton (

1991);

Sutch (

2006);

Robinson (

1986).

4.1. Rebuilding the Economy

The UK’s economic flexibility had been restricted during the war by mutual aid agreements with the US—a promise that Britain would not export goods received through the mutual aid programme. However, caveats to the agreement prevented the export of all goods within the category of a good received, hence barring the UK from exporting its own goods. Exports were at 28% of their 1938 level in 1944. The UK had also been a recipient of a large number of lend-lease import agreements, enabling the UK to receive US imports, deferring payment until after the war—including around a quarter of the total UK food supply.

Part of the post-war economic recovery was the challenge of extracting the UK economy from the US and Canadian economies, as it had become interwoven with them during the war. In the years following the war, all troops could not be immediately demobilised due to duties still required in Germany and the Pacific. Keeping on troops costs money, whilst also incurring the opportunity cost of lost output that they would otherwise contribute through employment in the UK economy. ‘Normality’ could not return until the UK had tackled a number of industry-level and employment-level factors, along with significant national economic troubles: a balance of payments deficit, shortages of steel, timber, coal and energy, and industry-specific skilled manpower. Initial prospects for growth were bleak.

There were two phases to the post-WW2 crisis: 1945–1947 and 1947-recovery. During 1945–1947, US enthusiasm for an early return to a liberal free-market economy underestimated the financial toll the war had taken on the UK.

Figure 2 depicts the annula GDP growth during these years.

In an attempt to gain funds to rebuild the economy, the UK secured a loan from the US in 1946 (the Anglo-American loan), settling for USD 1250 million less than needed (around USD 17.5 billion in today’s money, approximately GBP 12.76 billion given the exchange rate at time of writing)—and agreeing to conditions forcing through convertibility of sterling to the dollar in 1947.

The Sterling Convertibility Crisis following convertibility reignited UK and US financial panic due to an immediate drain on dollar reserves—Austin Robinson later reflected that this event ‘seemed at the time the most serious economic crisis of those years’, leading the government to ration bread and potatoes (which had not occurred during the war itself).

To climb out of the crisis, the UK needed to ascertain the exports required to finance necessary imports. Although export markets existed, other nations would rather use limited funds to rebuild their own infrastructures than create cash outflows through acquiring imports from Britain. Hence, the extent to which the UK could rely on these markets to acquire dollars was unknown.

Short-term expenditure was necessary to get out of the rut and create better conditions for growth. Britain had to prioritise—social investment (such as housing) was demoted in favour of capital formation. During the war, equipment had been worn out and not replaced, plants and machinery that were of no use in war time had been idle and were now in need of maintenance.

The UK set export targets—not usually used in peacetime—to incentivise industry to employ rationed raw materials towards achieving the necessary exports to provide cash inflows needed to meet domestic needs without imports. The managed economy sought to achieve the same aims that a free-market price system could provide, but enact them quicker through direct economic management. Following the convertibility crisis, the UK became a recipient of US ‘Marshall Aid’ intended to rebuild European economies.

Marshall Aid was conditional on recipients producing a viable plan for economic recovery by 1952, which drove the UK out of limbo towards long-term goal-setting. By 1951, the UK economy was stable enough that controls could be slowly lifted. The UK had achieved high employment, began to facilitate growth and had controlled wage inflation.

4.2. A Double-Edged Sword

Following the Second World War, Britain favoured the ‘social contract’ approach to recovery; however, this has been attributed as a cause of later industrial decline and a struggling economic position in comparison to international competitors. Direct state control of the economy had achieved record-breaking growth in the early war years, resulting in new factory space, technology, and skills.

Britain faced difficult decisions in reconciling wartime economic prowess with post-war financial destitution. As a consequence, to prevent the rapid depreciation of sterling and appreciation of prices that would ensue from immediate consolidation into the international liberal economy, Britain implemented controls and maintained a level of government intervention, enacting a gradualist strategy intended for a slow and steady return to the free-market economic order.

Nationalisation and a mixed economy approach were favoured in fear of a return to the interwar destitution, increasing the welfare state, including the formation of the NHS in 1948. The National Insurance (NI) scheme from the interwar period, which had caveats to eligibility and had in some cases precluded part-time work, was expanded, to cater for men and women, in both full and part-time work. NI provided state pensions and compensated for illness, maternity, unemployment, child support, funeral expenses and death or injury at work, whilst the 1948 National Assistance Act removed means-testing and expanded coverage to elderly and unemployed who had not paid contributions to the scheme.

Stephen Broadberry and Nicholas Crafts note that the ‘short-termist’ post-war economic strategies in Britain were by no means irrational given the limiting factors of the time. However, this ‘contract’ prevented industrial reforms necessary for long-term growth and productivity, leading to the industrial decline that marked later decades. Institutional barriers hampered Britain’s ability to keep pace with its international counterparts as frictions forming in the interwar years re-emerged following the Second World War—powerful decentralised ‘craft’ trade unions alongside monopolistic company structure.

Tackling the sudden macroeconomic shocks of the transition from the Second World War to peacetime prevented implementation of supply-side reforms needed to make the economy flexible to productivity gains and capable of evolving. This meant short-term recovery masked long-term inability for the economy to grow in line with international competitors.

4.3. Old Habits Die Hard

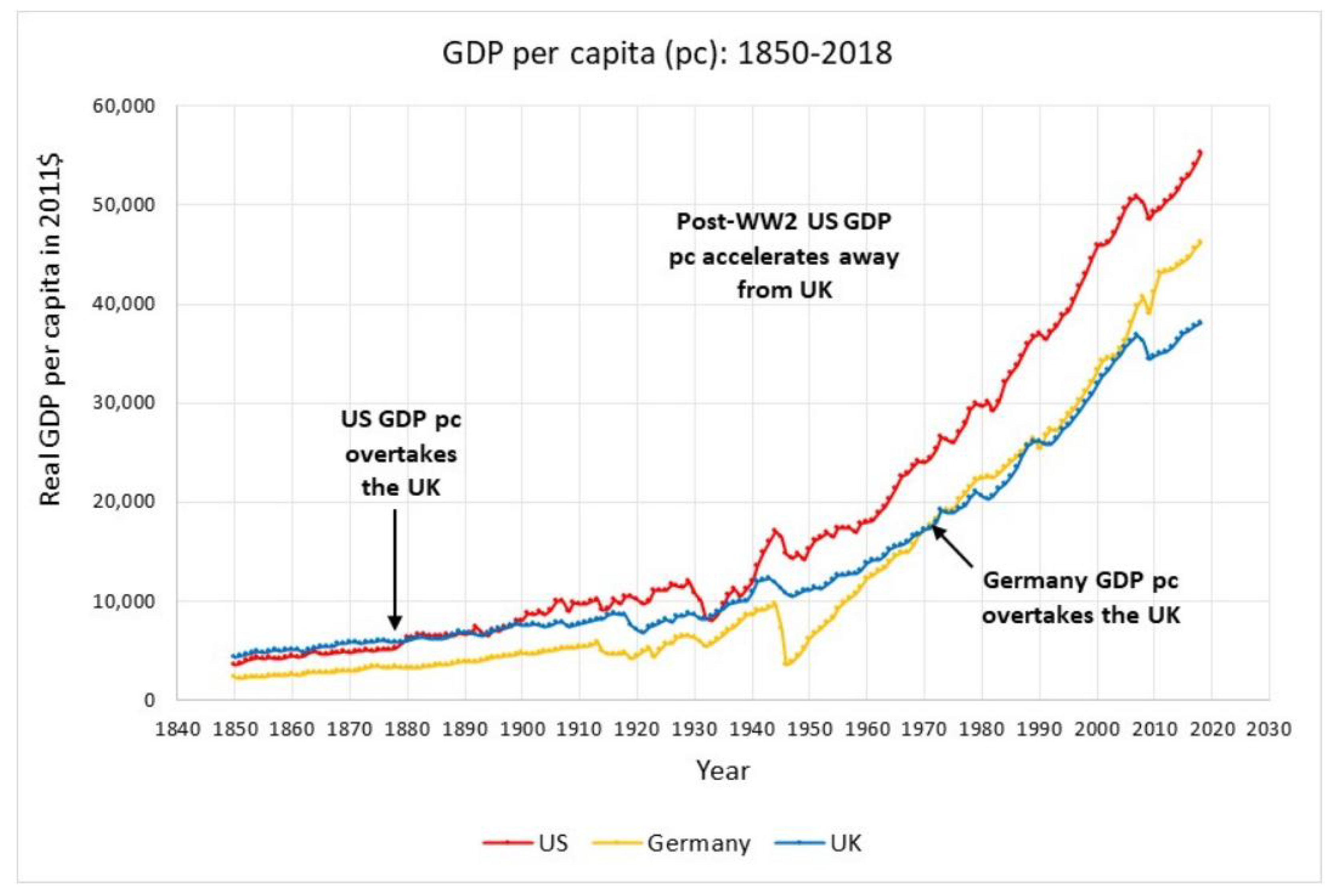

During the early post-war period, Britain did not invest in research and development to the extent of their US counterparts. Further, Broadberry and Crafts note that Britain was slow to adapt to the ‘Golden Age of European growth’, where opportunities were taken to increase total factor productivity in production, meaning the UK economy was overtaken by European competitors, see

Figure 3.

The US had accelerated capital replacement during the war whilst Britain had continued to use depreciated capital that required huge expenditure to replace in the post war period. Loss of manufacturing made the UK economy import-centric. Despite balancing payments with measures taken after the war, following the crisis, from the 1950s, Britain returned to importing more than it could finance from exports and invisibles.

Britain’s economic position became increasingly dependent on banking, finance and overseas insurance, manufacturing was increasingly outsourced and finished goods imported, whilst Britain encouraged foreign multinational corporations to establish bases in the UK. This created cash outflows from the UK to import cheaper goods produced abroad, whilst reducing the manufacturing base.

The ‘Golden Age of Capitalism’—the ‘good times’ following recovery from the war, constituting a global economic expansion—carried Britain’s economy along, masking its shortcomings in economic strategy. Britain’s economic position became globally economically subordinate following international economic reconfiguration, and lost its competitive global advantage.

The US became the dominant economy and Imperial strength was in decline, making Britain’s position as an importer of food and raw materials unsustainable. Global economic restructuring reduced connections between developed and developing economies, centring the global economy around transactions between developed economies. Increasing international trade in finished manufactured goods made the most highly developed industrial nations more dependent on production in each other’s markets.

Most significantly, Britain struggled to adopt the efficient large-scale divisional firm, leading British productivity performance to be weak in comparison to its US counterparts. Collusion, monopoly power and decentralised powerful ‘craft’ trade unions impeded the long-term productivity potential necessary to maintain high rates of future growth. As the US ‘deskilled’ the workers on the production line, it focused on improving human capital in managerial practices.

In the UK, resistance to rationalisation, which began in the 1930s, continued into the post-war era, meaning Britain had a lack of focus on managerial training for hierarchical corporate capitalism. Unions and management resisted the necessary reskilling and formation of human capital needed to establish effective managerial practices.

Prior to the war, Britain had sustained a competitive position through highly skilled workers. However, in the post-war economy there was a decline in focus in the British apprenticeship, which deskilled the working population. However, due to resistance to rationalisation, Britain did not compensate with managerial training. As a result, Britain suffered an overall lack of human capital accumulation relative to international counterparts, putting the nation in productivity catch-up, leading to lack of growth opportunities.

The UK became more interested in the US methods of production, but was slow to adopt capital-intensive mass manufacturing practices, due to resistance to standardisation from workers and employers. In the late 1940s, there was significant opposition to antitrust laws intended to break up monopoly power, from workers and employers, limiting the future growth potential through market competition of the private sector.

The US transition to ‘competitive managerial capitalism’, where salaried managers decide the allocation of resources, manpower and operations for the present and future, has been attributed as a key determinant of US large-scale firm success. Britain maintained ‘personal capitalism’, a continuation of the Second Phase of the industrial revolution—businesses are often family-owned, the owners dictate the day-to-day operations and extract profit from the business as dividends, which hindered progress towards integrating the large-scale firm into the British economy.

Lack of adaptability meant the UK lost its competitive edge, leading to industrial decline. In the post-war period, it was expected that advanced industrial nations would experience employment sector transition from manufacturing to services, leading to a new stable economic system: the service economy. With the dawn of ‘post industrialisation’, employment ought to shift gradually into higher skilled, higher waged jobs in services.

The post-war economic restructuring in the UK, however, led to deindustrialisation. The transition away from manufacturing accelerated, but higher waged services jobs failed to appear. Manufacturing employment went into decline from 1966, falling 34.5% (loss of 2.9 million jobs) in the 17 years up to 1983—of this decline, 1.5 million jobs were lost between 1979 and 1983 as a result of policies enacted to tackle inflation, leading to the 1980 recession.

Although the UK experienced its best growth on record in the period following the war, other nations were growing quicker and were proving more adaptable to the new economic order, leading to relative decline of the British economy. The US led in GDP per employed person in the 1950s; however, the UK was overtaken by countries which had lower standards of living and productivity in 1950, and has been slow to close the gap to the US.

Due to lack of international competitiveness, the UK economy became more vulnerable to unexpected declines in international economies. As Britain lost its competitive position, it became a reactive player in the global economy. Government economic policy continued attempts to increase investment and output but they proved futile against strong international competition. Planning measures were continually put on the backburner by exchange rate crises calling for deflationary policy, leading to further decreases in productivity and worsening balance of payments deficits. Lack of both investment and industrial prowess made the new globalised economy a vulnerable situation for the UK economy. Recovery was slow from the economic downturns throughout the 1970s, as the UK had economic rigidities preventing speedy reconstruction. Britain’s share of world trade continued to decline and economic growth was suffocated by high inflation throughout the 1970s.

5. Can Governments Plan Growth? Lessons from Bretton Woods

Economic recovery is, by definition, a period where the economy returns to a trend of growth. Although we would expect this to accompany a decrease in unemployment, a rise in business activity and growing GDP, on exiting a recession, unemployment may not decline. The key factor in determining whether a recession, depression or economic crisis is ending is that economic growth returns. Therefore, economic policy intended to navigate out of a crisis is a planned exit enabling the economy to grow its own way out of crisis. This section draws on references

Bordo (

2017);

Bryan (

2013);

The National Archives (

2008a).

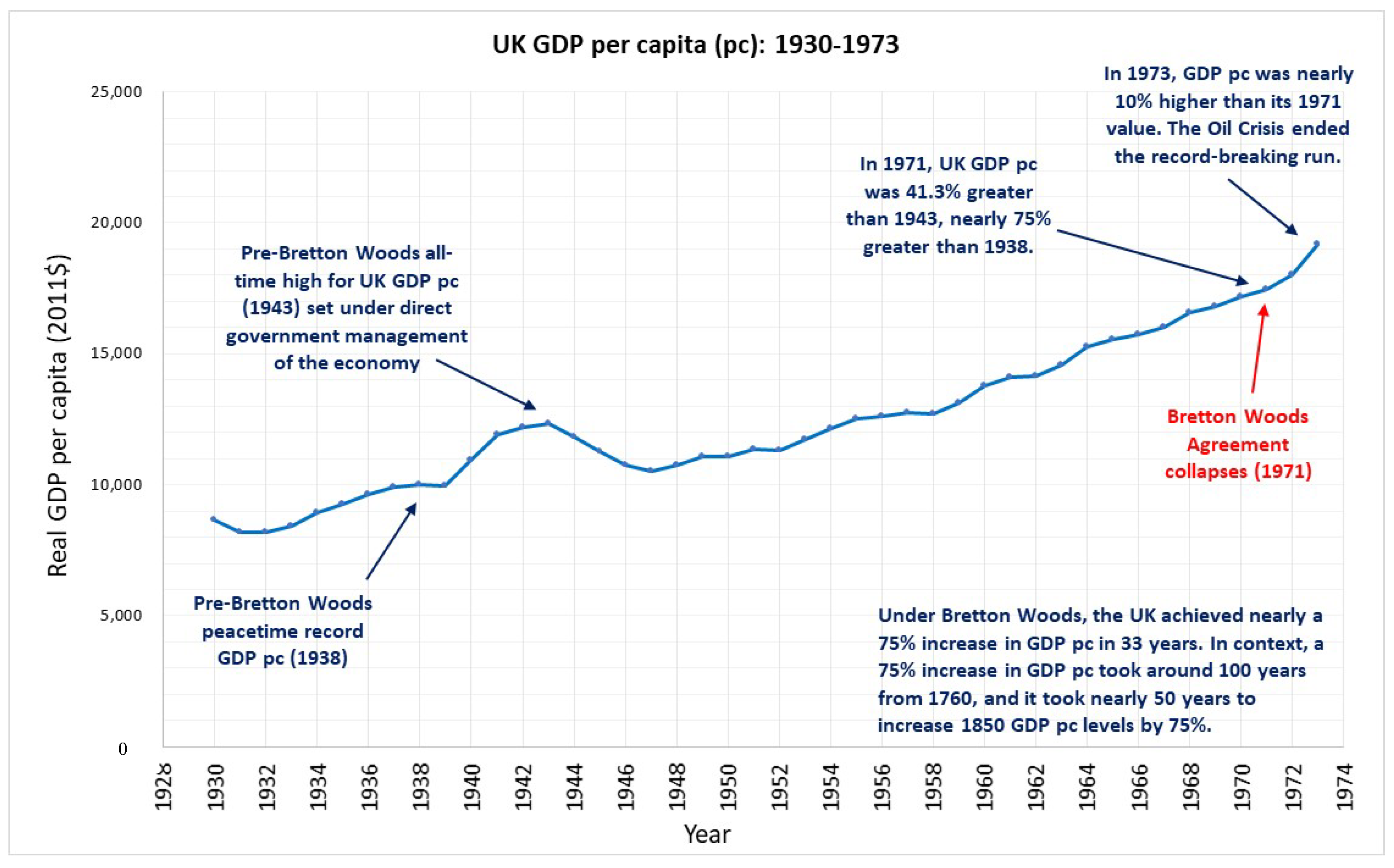

5.1. A Golden Age

The period of economic stability and record growth following the Second World War can be attributed to the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944 and serves as a good study in ‘planning’ growth. The agreement also identifies significant international economic structural change that crafted the shape of the world economy in the post-war period. It redefined the UK’s place in the world economy—by denoting the US Dollar as the world’s reserve currency, it demoted pound sterling from global prominence and removed Britain from being the financial capital of the world. The Agreement endorsed global use of GNP as a competitive metric to actively monitor wealth and growth across nations party to the Agreement. Further, the conference gave rise to international institutional changes to global finance, namely the inauguration of the IMF and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (which later became part of the World Bank)—the birth of the intergovernmental institution era.

With the fear of a return to the interwar period’s erratic exchange rates, unfavourable for growth, it was decided that a constructed monetary system could enable the world economy to navigate out of the Second World War in a more stable market environment. Returning to the gold standard was, throughout the early 20th century, a technique used in an attempt to stabilise currencies. At the time of Bretton Woods, the US held two thirds of the world’s gold reserves. It was decided that many international currencies would be pegged to the US dollar and that the Dollar would be convertible to gold. Any country could exchange Dollars for gold, on demand, via the US. In the early post-war period this system was an immense success. It led to exchange rate stability, enabling economies to re-establish themselves in the post-war period without the need to interrupt recovery. The Dollar-peg avoided the fluctuations in exchange rate that can cause inflationary pressures, hence avoided the need for recurrent changes in monetary policy. The stability brought record levels of growth—during this time, the UK surpassed any level of GDP per capita that it had experienced in its history, see

Figure 4.

5.2. Under Pressure

For the Bretton Woods Agreement to continue, it necessitated that all member countries continue to adhere to the monetary outlines of the agreement—breaking the pact would ruin the agreement. This is what spelled the death of Bretton Woods.

Nations who were party to the Bretton Woods Agreement held Dollar reserves that could be exchanged for gold. By 1959, the outstanding Dollars held by nations party to the Agreement matched US gold reserves and pressure began to mount that the gold reserves would not suffice if the outstanding Dollars grew and needed to be converted into gold. A series of Acts passed by the US government to dissuade gold conversion ensued throughout the early 1960s.

In 1965, the US, whilst running a balance of payments deficit, encountered a series of expenditures, which would need to be financed. As a result, they implemented expansionary monetary policy in an attempt to fund the shortfall created by increased expenditure in the Vietnam War and President Johnson’s Great Society (a sweeping overhaul of public services). Nations holding Dollar reserves needed a way to store them. As a result, they invested in Treasury securities (US government bonds).

Increased demand for Treasury securities increased their price (as they are fixed in number). As paper dollars were exchanged for the Treasury securities sold by the US, the US gained more paper money by securities being sold at a higher price, hence increasing money supply. Inflationary pressure grew, leading to fears that instability of the Dollar would lead to an international clamour for US gold reserves.

In 1971, US President Nixon suspended convertibility to protect US gold reserves and the Bretton Woods Agreement collapsed. This was a significant change as world currencies became free-floating for the first time—under the agreement sterling had been devalued twice (in 1949 and 1967) in order to maintain the exchange rate peg without free-floating currency exchange. The Bretton Woods Agreement illustrates the highs and lows of planning economic growth stability. Although the period of stability benefited many nations, the period that subsequently arose, of high inflation, recessions and economic turbulence, was a stark contrast.

6. The 1980–1981 Recession

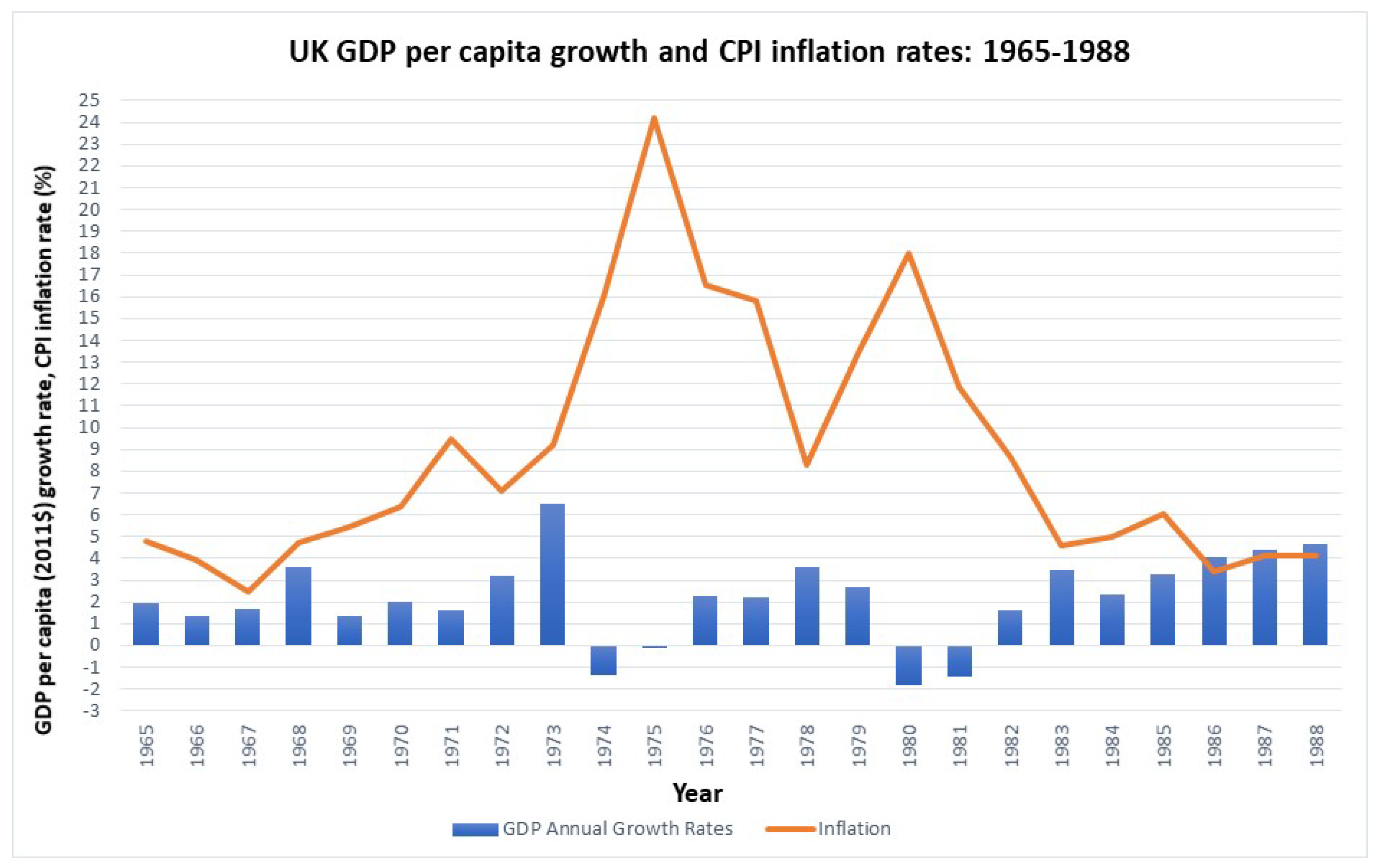

Britain was cossetted by steady economic growth following the war, benefitting from international prosperity through exchange rate regimes. However, the glory days soon faded into memory, as growth embarked on a rocky path through the 1970s, see

Figure 5. The political and economic events of the 1970s led to high inflation, high interest rates and poor productivity which was combined with a loose fiscal policy. Growth rates were volatile and the economy was grinding to a halt. The incoming Conservative government took drastic action. This section draws on references

Andersen (

2010);

Elhefnawy (

2021);

Heyes et al. (

2017);

Paker (

2020);

Pissarides (

2013);

Rose et al. (

1984).

6.1. New Ideals

The year 1971 saw the collapse of Bretton Woods agreement when US President Nixon suspended convertibility of the US Dollar to gold, breaking the agreement intended to stabilise global economies through the post-war period. In 1973, the Oil Crisis meant that a shortage in oil raised oil prices leading to inflation. This spelled the start of a rocky decade. Since the 1973 oil crisis, British North Sea Oil had become lucrative, making the UK a net exporter of oil and masking the decline in British industry. Monetary supply targeting and reduced government spending had been implemented during the 1970s in an attempt to reduce inflation, but had not made great inroads by the end of the 1970s.

Frugal government spending led to limits in public sector pay rises in 1978, which created mass strikes in demand of greater pay rises (especially given that rising inflation decreases the real value of a set wage rate—fewer goods can be bought as prices increase, if the wage remains constant). The 20% pay increase achieved by lorry drivers in January 1979 set the precedent for calls for pay increases.

The Second Oil crisis of 1979 sent inflation spiralling upwards. Margaret Thatcher came into power, implementing deflationary policies to curb inflation, raising the interest rate and triggering the 1980–1981 recession. Monetarist policies and fiscal restraint led to a speedy recovery of growth; however, employment did not respond, leading to long-term stagnation in the labour market. Major strikes became a lasting image of the 1970s and early 1980s era and its recessionary environment.

The year 1979 is accredited as the transition to neoliberalism, signifying a shift in the political ideology associated with UK economic policy. The shift to neoliberalism led to increased focus and reliance on ‘services’, increased deregulation in financial sectors and increased interest rates, negatively impacting industrial sectors. Thatcher’s government employed monetarist monetary policies, which target the growth rate of money supply to control the economy, purporting that the amount of money in the economy is the major driver of economic growth.

Economic policy in the UK shifted away from the welfare state towards tightening of fiscal policy. The government decreased public sector borrowing, increased taxes and imposed cuts in government spending. According to Meredith Paker, ‘fiscal restraint’ remained the government’s economic focus following the growth in output which ended the 1980–1981 recession. The Thatcher government also implemented a series of Acts to reduce trade union power. However, the services industry did not create sufficient cash inflow to balance the trade deficit caused by imports of finished goods.

Figure 6 depicts GDP growth during the 20-year period.

6.2. Mind the Gap

Economic restructuring due to the 1980–1981 recession represented an acceleration of manufacturing decline and industrial plight. The recovery from the recession can be viewed as ‘jobless’— the second half of 1981 saw an increase in GDP growth, leading the economy sharply out of the recession as a result of stunting inflation but the growing economic environment was not reflected in employment levels.

The recession itself lasted five quarters but employment continued to contract until the second quarter of 1983—25 months after the recession had ended—peaking at 11.9% in 1984. It was still high by 1987 (over 10%). Britain’s poor productivity performance was masked by net exports of North Sea Oil at a time when oil was in high demand due to the Oil Crises. Even when removing the contribution of North Sea Oil to the recession recovery, GDP growth increased before unemployment reached its peak.

Over 3 million became unemployed after the 1980–1981 recession. Despite promising rebound growth, high unemployment underutilises human capital in the economy, producing inefficiencies. If employed, the workforce would increase productivity through labour hours worked and if acquiring new skills, build human capital.

Labour reallocation was a significant driving factor of the slow employment response to the recession recovery. Displacement of workers from permanently damaged sectors, such as heavy industry, led the unemployed to seek work in new sectors, requiring new jobs to be created. In theory, the rebound growth from an economic downturn should re-employ those laid off by recessionary conditions, into their previous industries.

Output often resumes following a recession in the industries that were strong before the recession. Due to accelerated industrial decline and drastic deterioration of the manufacturing sector during the 1980–1981 recession, which continued to contract after the recession, jobs in heavy industries were no longer available to re-hire unemployed workers.

The permanent decline in heavy industry had a domino effect on associated industries that supplied and facilitated key sectors, creating further job loss, and eliminating a network of major sources of British economic growth. Across the board, employment in tradables (manufactured goods) decreased and employment in non-tradables (non-tangible sectors, such as services) increased, with large increases in employment in banking and finance.

Traditional ‘British’ industries suffered extreme job loss whilst employment in the financial sector grew, representing structural change in the British economy and worsening the class divide with respect to employment opportunities.

In the 1979–1987 period, the UK economy began to display job polarisation, whereby the central income jobs—‘middle-skilled’ jobs—began to disappear, whilst the lowest and highest earning jobs experienced growth in employment share. Although this effect was not large during 1979–1987, it demonstrates momentum in the direction of a polarised employment market, signifying further structural change in employment. Britain became established in skilled trades and skilled middle-income occupations from the latter half of the Industrial Revolution.

Polarising incomes contributes to deskilling (which reduces productivity) in working class and lower middle-class jobs and also reduces social mobility—the likelihood that a low earner can leap into a high earning profession is markedly reduced when the bridge of incomes in between is removed. The polarisation that occurred during and following the recession was between-industry polarisation—it was driven by the larger shift in labour reallocation away from traditional industries.

Regional disparities worsened during the 1980–1981 recession with growth in the share of employment in the South of the UK and a reduction across the North, Wales and West Midlands, particularly felt in the North West of England. Once recession recovery began, the Southern draw of employment continued and the regions affected by the recession continued to experience deterioration in employment opportunities. Regional differences are attributed as being caused by the high concentration of industries that rapidly declined in the North, West Midlands and Wales.

Employment in the public sector fell after 1979, particularly in the industries nationalised during the post-war years. ‘New’ industries of the interwar years, such as car manufacturing, also experienced decline. Theories suggesting that post-industrialism would enable services to gather unemployed workers from manufacturing were proven to be incorrect in the UK economy. Due to the 1980 recession, 500,000 jobs were lost in services, indicating that the British economy was shedding jobs in secondary and tertiary employment. Manufacturing levels in 1984 equalled 1968 levels—as with the interwar years, the UK economy was growing to return to its position of decades earlier.

6.3. Dire Straits

Despite the political-economic shift away from the post-war structure in 1979, deindustrialisation continued. The 1980–1981 recession accelerated the deindustrialisation effects set into motion following the Second World War and worsened the competitive landscape between the UK and other industrialised nations, such as the US.

The decline in British industry was much more drastic and permanent than the US post-recession economy, which experienced rebounds in major industries. Contracting employment in the key sectors of energy, transport, water, mining and communications only occurred in the UK. Industries that declined during and following the recession did not recover; this signifies a permanent structural impact on the British economy, impairing future industrial output, which had been a key driver of British growth.

The continued decline in the British export market in the 2000s can be traced back to the industrial decline surrounding the 1980–1981 recession, demonstrating the permanence of the restructuring effects surrounding the 1970s–1980s. In this respect, the UK’s performance is not comparable to the US, which experienced a strong bounce-back following the rocky 1980s, with (manufacturing) output rising 30% by 2000 from its 1989 level. During this time, British output grew only 4%.

Although the decline in traditional heavy industries is not unique to the UK economy (the US has experienced reductions in those same sectors), it is unusual that those industries have not been replaced by newer manufacturing markets, such as computers. In contrast to the UK, the US government sustains pivotal areas of the economy through government spending, which encourages materials for US-manufactured finished products to be provided by other US-based industries, facilitated by the free-market economy. Investment in the shale gas industry created low-cost energy for the chemical industry, which is a key contributor to US economic growth. Further, a ready supply of gas lowers the cost of input factors in all US industries, leading to greater growth potential.

Nader Elhefnawy accredits the UK’s failure to shift from fossil fuel industries and the lack of movement into new markets, such as technology, as stifling UK economic growth potential, causing the declining industries to dominate economic trends. Facilitating a transition to new sources of rapid growth, such as computers, could have reduced long-term unemployment, increased British output and stimulated long-term growth, instead of enacting surface-level short-run rebound growth to recover GDP.

6.4. Identity Change

Socio-cultural restructuring as a result of the Thatcherist policies that marked the 1980–1981 recession and its subsequent years were significant. The era of the loan made consumer credit opportunities widespread for the British consumer. The UK experienced a rise in use of mortgage finance, intended for home improvements, for instant purchase of consumer goods, which led to a prevalence of consumer durables and electrical goods in the home. However, this masked underlying economic inequalities.

As of 1984, around 15 million people lived on the margins of poverty, up 3.5 million in 5 years. The conflict between material possessions and economic inequality in British society redefined identity. It has been suggested that this era marked a transition from the lived experience as being defined by class structure and employment identity—a collective experience—to a rise in individualism, with experience marked by material social status.

A significant shift in the perception of class, wealth and value was marked by the craze of home ownership as marking societal status—council houses could be sold to their tenants, creating a new rift in the working class and influencing people’s perceptions of their own political preferences and social standing. Hence, despite crippling unemployment, the cultural mindset shift towards Conservatism in previously staunch working-class households led to a re-election for Thatcher with an overwhelming majority (a process termed ‘class dealignment’).

Following the war, ‘citizenship’ as a social structure was defined by the social contract formed by the government, emphasising access to the benevolent welfare state, enabling free healthcare and social support and a dialogue with a public-centric government. However, the restructuring of the Thatcher-era deconstructed the sense of national citizenship, leading people to become insular and self-focused.

During the deindustrialisation process, economic decline was spurred on by government policies in the late 1970s and early 1980s which indirectly threatened the collective identity of citizenship. The nation-state was increasingly ousted in favour of multinational corporations and opportunity became decided by the free-market, instead of government intervention. We build on some of the long-term implications of the socio-economic restructuring of the 1980s in third paper in our series on UK economic growth, where we survey the impacts of inequality due to restricted access to growth.

7. The 2008 Financial Crisis

The negative impact of a highly interconnected economy and a deregulated financial sector came to the fore with the 2007–2008 Financial Crisis, which resulted from ripples across the global economy as US investment banks collapsed due to exposure to subprime mortgages. Subprime loans enabled people to secure mortgages for properties without extensive credit checks and income documentation.

Governments could be inclined to accept a prevalence of subprime loans to encourage investment and create economic buoyancy. When house prices were rising, loan repayments were made; however, when house prices started to decline, defaults increased. If large swathes of borrowers default simultaneously, lenders risk serious liquidity difficulties and banks can collapse. An increasingly globalised economy creates networks of foreign financing in domestic companies worldwide, which can create channels through which financial distress can spread and international financial systems can collapse.

The effects of the recession had spread to Europe by summer 2007 and all countries were in recession by late 2008. With construction and finance hit hard first, the recession spread throughout the economy like wildfire, and GDP contracted for five consecutive quarters. The beginning of 2008 saw the effects of the recession through a rise in unemployment, due to the shock to aggregate demand in the market.

Figure 7 shows annual GDP growth during this period.

Prior to the 2008 Financial Crisis, the UK had established a steady state to its economy, despite falling behind major competitors. Although the world suffered the repercussions of the Financial Crisis, significantly, as other nations began to rise out of the recession around the first quarter of 2009, the UK struggled to gain ground, establishing a new equilibrium at the low level of output and employment. Christopher Pissarides describes this malaise as due to the UK’s macroeconomic rigidities—few or no new jobs were being created to absorb the high levels of unemployed.

7.1. Stuck in the Mud

The Financial Crisis led to the deepest UK recession since the Second World War and was the world’s worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. Inter-bank lending ceased as banks became reluctant to lend to other banks in the fear that they would not be paid back. Financial markets started to freeze up, leading to difficulty securing credit for individuals and businesses.

The UK government bailed out several major banks and enacted austerity in the aftermath to reduce the trade deficit. It took five years for UK GDP to regain its pre-crisis levels. Ten years on from the crisis, UK productivity was still stalling, wage rate rise had been weak and economies globally were still entrenched in debt. The discipline of Economics and the trustworthiness of financial institutions took a hit in the public eye as a result of the crisis, as many believed the extent of the financial chaos could have been avoided.

The subsequent structural reform to the financial sector sought to prevent a repeat of the crisis, but political action, taken after the crisis period had subsided, received condemnation over the social impacts of fiscal restraint and long-term sustainability of the UK economy.

During the recession, the UK did not display structural difficulties at a microeconomic level, meaning there were little or no frictions in matching unemployed people to job vacancies; however, the economy had stagnated at a low level of employment and lack of new job creation prevented the unemployment rate from decreasing.

Pissarides attributes the functioning market at the microeconomic level to reforms following the 1980–1981 recession—structural changes shifted the incentive focus towards employment through lower taxation and more strict unemployment support, creating greater labour market flexibility which could absorb the structural difficulties other nations experienced on the pathway out of the Financial Crisis. (Although, the financial deregulation measures implemented during the Thatcher years are attributed as one of many contributory factors to the fragility of UK financial institutions when the Financial Crisis emerged).

Government policy out of the Financial Crisis was similar in form as the 1980–1981 policies of fiscal restraint, with the coalition government reducing government and public sector spending. However, the intention that the private sector would absorb the unemployed appearing from the public sector did not materialise as expected. The contracting public sector had a negative knock-on effect on aggregate demand in the market, meaning the private sector was limited and not able to expand to create jobs to absorb the unemployed.

The sovereign debt crisis that occurred following the 2008–2009 recession in Southern Europe reduced export potential for UK companies into the Eurozone, further limiting private sector expansion in the UK. The private sector was able to take over in the jobs that were lost in the public sector but had no ability to expand past that point, leading to a new lower-level steady state of employment. Due to low-level employment and stunted private sector expansion, productivity was heavily implicated, reducing potential for strong long-term growth once the recession subsided.

7.2. Austerity

In the wake of the Financial Crisis, the UK coalition government turned to fiscal consolidation and austerity measures in 2010 as a strategy to mitigate the effects of spiralling budget deficits that had emerged in order to finance the crisis. The measures included an increase in VAT to 20% (increased taxation) in 2011. The UK had attempted ‘quantitative easing’ programmes in the early throws of the recession—increasing money supply so that the government can purchase private assets with the new money.

Pissarides comments that this was not at an adequate level to ‘offset the fiscal austerity’ (the cuts in public spending). Fiscal austerity immediately decreases aggregate demand, spreading contraction throughout the economy. However, austerity measures to suppress demand are not a long-term solution—to restore demand necessary for driving output and sustaining growth, the economy requires structural change in institutions and reforms in the labour market.

Surrounding fiscal austerity, the government promoted a dialogue that public services cost too much and that the market and its constituent organisations can operate the nation, cutting public sector budgets and reducing funding for public services. Austerity measures were officially brought to a close in 2015/16, when George Osborne (then Chancellor of the Exchequer) declared that the national deficit as a share of national income had decreased by half and that selling shares in banks (gained as a result of the bank bailout of 2008) was regaining taxpayers’ money.

The measures succeeded in curbing some of the deficit but have been extremely controversial. A UN poverty envoy accused the government of ‘entrenching high levels of poverty and inflicting unnecessary misery’ with the measures, which have been attributed to worsening the socio-economic inequalities and health and social outcomes of many UK citizens. Child poverty, unemployment and the number of families (even those with at least one working parent) requiring food banks rose during the ‘Austerity Age’.

Austerity does not so much ‘fix’ the economy through investments in innovation and skilling to promote future growth, but stalls the balance of payments from escalating further, which can lead to gaps in productivity relative to international counterparts when measures are removed. Critics and supporters continue to debate the fiscal and societal costs of austerity as a suitable policy tool in times of economic deterioration. There does not yet seem a consensus on prolonged austerity following economic turbulence, such as the 2008 Financial Crisis, and the battle between fiscal stimulus and restraints continues to be waged in political circles.

7.3. Puzzling Productivity

Many economists and economic historians have examined the ‘productivity puzzle’ that has emerged in the wake of the Financial Crisis; the UK’s Office for National Statistics claimed ‘it is arguably the defining economic question of our age’. UK labour productivity, measured in real GDP per hour worked, was merely 2% higher in the fourth quarter of 2018 than in the fourth quarter of 2007 (the pre-crisis peak). The UK economy has been lethargic in retrieving pre-crisis growth, see

Figure 8.