Psychological Impact of Newborn Screening for 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA Carboxylase Deficiency: The Parental Experience

Abstract

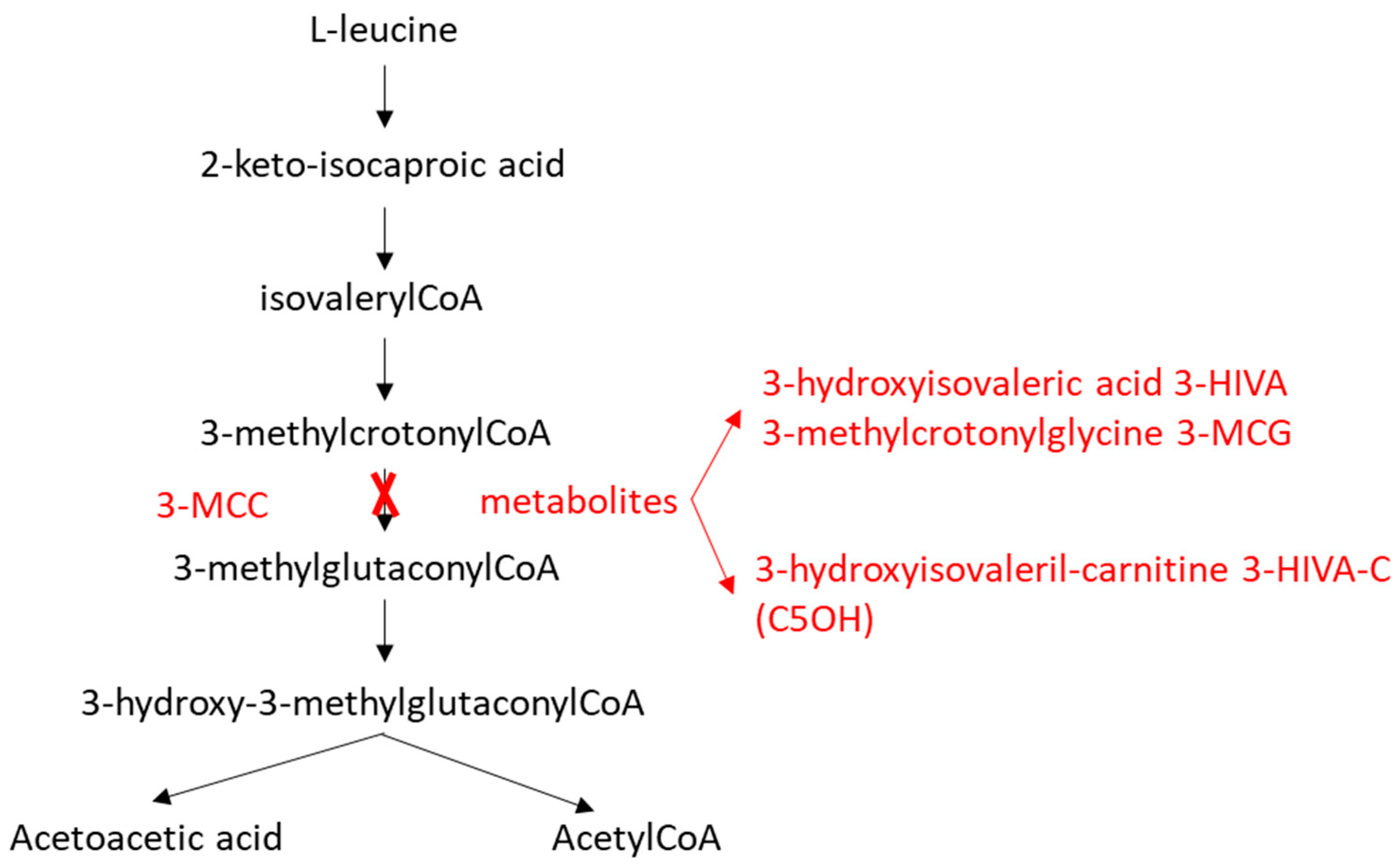

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Newborn Screening

2.2. Confirmatory Testing

2.3. Management and Follow-Up

2.4. Psychological Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

3.1. Newborn Screening and Confirmatory Testing

3.2. Follow-Up

3.3. Psychological Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3-MCCD | 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency |

| 3-MCC | 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase |

| 3-MCG | 3-methylcrotonylglycine |

| 3-HIVA | 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid |

| HIVA-C/C5OH | 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine |

| DBS | dried blood spot |

| GC-MS | gas chromatography/mass spectrometry |

| IMD | inherited metabolic disorders |

| MS/MS | tandem mass spectrometry |

| NBS | newborn screening |

| PPV | positive predictive value |

| SD | standard deviation |

Appendix A

| Newborn | Mother | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Sex | Origin | C5OH (Cutoff ≥0.8 µmol/L) * | C0 (nv 11–51 µmol/L) * | Urinary Organic Acids | C5OH (nv 0.08–0.5 µmol/L) * | C0 (nv 11–51 µmol/L) * | Urinary Organic Acids |

| M1 | F | Italy | 2.24 | 13.2 | Neg | 0.87 | 19.2 | 3-MCG, 3-HIVA |

| M2 | M | Moldova | 2.42 | 11.0 | Neg | 3.69 | 12.1 | 3-MCG, 3-HIVA |

| M3 | M | Italy | 0.98 | 34.1 | Neg | 2.12 | 19.4 | 3-MCG, 3-HIVA |

| M4 | M | Nigeria | 4.48 | 8.9 | Neg | 6.8 | 5.6 | 3-MCG, 3-HIVA |

| M5 | F | Italy | 1.24 | 22 | Neg | 1.07 | 18.5 | 3-MCG, 3-HIVA |

| M6 (Sibling of M4) | F | Nigeria | 4.26 | 7.1 | Neg | |||

| M7 | F | Senegal | 0.85 | 8.3 | Neg | 1.77 | 12.6 | 3-MCG, 3-HIVA |

| M8 (Sibling of M7) | F | Senegal | 1.12 | 9.5 | Neg | |||

| M9 | F | Tunisia | 2.45 | 16.2 | Neg | 3.71 | 13.2 | 3-MCG, 3-HIVA |

| Question 1 | Question 2 | Question 3 | Question 4 | Question 5 | Question 6 | Question 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 Father | 10 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 7 |

| P1 Mother | 10 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| P2 Father | 4 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 6 |

| P2 Mother | 10 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 10 |

| P3/P8 Father | 8 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| P3/P8 Mother | 9 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 10 |

| P4 Father | 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 7 |

| P5 Father | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 8 |

| P5 Mother | 10 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 10 |

| P6 Father | 7 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 10 |

| P7 Father | 10 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 10 |

| P7 Mother | 10 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 10 |

| P9 Father | 5 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 9 |

| P9 Mother | 9 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 9 |

References

- Gallardo, M.; Desviat, L.R.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Esparza-Gordillo, J.; Pérez-Cerdá, C.; Pérez, B.; Rodríguez-Pombo, P.; Criado, O.; Sanz, R.; Morton, D.; et al. The Molecular Basis of 3-Methylcrotonylglycinuria, a Disorder of Leucine Catabolism. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 68, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, M.R.; Almashanu, S.; Suormala, T.; Obie, C.; Cole, R.N.; Packman, S.; Baumgartner, E.R.; Valle, D. The molecular basis of human 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kremer, R.D.; Latini, A.; Suormala, T.; Baumgartner, E.R.; Laróvere, L.; Civallero, G.; Guelbert, N.; Paschini-Capra, A.; Depetris-Boldini, C.; Mayor, C.Q. Leukodystrophy and CSF Purine Abnormalities Associated with Isolated 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA Carboxylase Deficiency. Metab. Brain Dis. 2002, 17, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, S.C.; Polanetz, R.; Maier, E.M.; Heidenreich, S.C.; Niederer, B.; Mayerhofer, P.U.; Lagler, F.; Koch, H.-G.; Santer, R.; Fletcher, J.M.; et al. Newborn screening for 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency: Population heterogeneity of MCCA and MCCB mutations and impact on risk assessment. Hum. Mutat. 2006, 27, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.; Carter, J.M.; Cederbaum, S.D.; Neidich, J.; Gallant, N.M.; Lorey, F.; Feuchtbaum, L.; Wong, D.A. Analysis of cases of 3-methylcrotonyl CoA carboxylase deficiency (3-MCCD) in the California newborn screening program reported in the state database. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2013, 110, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, E.W.; Chace, D.H. Automated Tandem Mass Spectrometry for Mass Newborn Screening for Disorders in Fatty Acid, Organic Acid, and Amino Acid Metabolism. J. Child Neurol. 1999, 14, S4–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeberl, D.D.; Millington, D.S.; Smith, W.E.; Weavil, S.D.; Muenzer, J.; McCandless, S.E.; Kishnani, P.S.; McDonald, M.T.; Chaing, S.; Boney, A.; et al. Evaluation of 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency detected by tandem mass spectrometry newborn screening. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2003, 26, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roscher, A.A.; Liebl, B.; Fingerhut, R.; Olgemöller, B. Prospective study of MS-MS newborn screening in Bavaria, Germany. Interim results. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2000, 23, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, A.; Lindner, M.; Kohlmüller, D.; Olgemöller, K.; Mayatepek, E.; Hoffmann, G.F. Expanded Newborn Screening for Inborn Errors of Metabolism by Electrospray Ionization-Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Results, Outcome, and Implications. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcken, B.; Wiley, V.; Hammond, J.; Carpenter, K. Screening Newborns for Inborn Errors of Metabolism by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2304–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Weng, C.; Hong, F.; Tong, F.; Yang, R.; Yin, X.; Yu, P.; Huang, X.; et al. Identification of eight novel mutations and transcript analysis of two splicing mutations in Chinese newborns with MCC deficiency. Clin. Genet. 2015, 88, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’cOnnor, K.; Jukes, T.; Goobie, S.; DiRaimo, J.; Moran, G.; Potter, B.K.; Chakraborty, P.; Rupar, C.A.; Gannavarapu, S.; Prasad, C. Psychosocial impact on mothers receiving expanded newborn screening results. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 26, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchbinder, M.; Timmermans, S. Newborn Screening for Metabolic Disorders: Parental Perceptions of the Initial Communication of Results: Parental Perceptions of the Initial Communication of Results. Clin. Pediatr. 2012, 51, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rips, J.; Almashanu, S.; Mandel, H.; Josephsberg, S.; Lerman-Sagie, T.; Zerem, A.; Podeh, B.; Anikster, Y.; Shaag, A.; Luder, A.; et al. Primary and maternal 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency: Insights from the Israel newborn screening program. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2016, 39, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruoppolo, M.; Malvagia, S.; Boenzi, S.; Carducci, C.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Teofoli, F.; Burlina, A.; Angeloni, A.; Aronica, T.; Bordugo, A.; et al. Expanded Newborn Screening in Italy Using Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Two Years of National Experience. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, D.S.; Terada, N.; Millington, D.S. Automated analysis for free and short-chain acylcarnitine in plasma with a centrifugal analyzer. Clin. Chem. 1992, 38, 2215–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Kawana, S.; Hasegawa, Y.; Yamaguchi, S. Simplified Method for the Chemical Diagnosis of Organic Aciduria Using GC/MS. J. Chromatogr. B 2010, 878, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisbren, S.E.; Albers, S.; Amato, S.; Ampola, M.; Brewster, T.G.; Demmer, L.; Eaton, R.B.; Greenstein, R.; Korson, M.; Larson, C.; et al. Effect of expanded newborn screening for biochemical genetic disorders on child outcomes and parental stress. JAMA 2003, 290, 2564–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- On behalf of the Canadian Inherited Metabolic Diseases Research Network (CIMDRN); Siddiq, S.; Wilson, B.J.; Graham, I.D.; Lamoureux, M.; Khangura, S.D.; Tingley, K.; Tessier, L.; Chakraborty, P.; Coyle, D.; et al. Experiences of caregivers of children with inherited metabolic diseases: A qualitative study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2016, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verberne, E.A.; Heuvel, L.M.v.D.; Ponson-Wever, M.; de Vroomen, M.; Manshande, M.E.; Faries, S.; Ecury-Goossen, G.M.; Henneman, L.; van Haelst, M.M. Genetic diagnosis for rare diseases in the Dutch Caribbean: A qualitative study on the experiences and associated needs of parents. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 30, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, M.R.; Dantas, M.; Suormala, T.; Almashanu, S.; Giunta, C.; Friebel, D.; Gebhardt, B.; Fowler, B.; Hoffmann, G.F.; Baumgartner, E.; et al. Isolated 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA Carboxylase Deficiency: Evidence for an Allele-Specific Dominant Negative Effect and Responsiveness to Biotin Therapy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 75, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morscher, R.J.; Grünert, S.C.; Bürer, C.; Burda, P.; Suormala, T.; Fowler, B.; Baumgartner, M.R. A single mutation in MCCC1 or MCCC2 as a potential cause of positive screening for 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012, 105, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, M.F.; Suormala, T.; Randolph, A.; Coelho, D.; Fowler, B.; Valle, D.; Baumgartner, M.R. 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency: Mutation analysis in 28 probands, 9 symptomatic and 19 detected by newborn screening. Hum. Mutat. 2005, 26, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ficicioglu, C.; Payan, I. 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA Carboxylase Deficiency: Metabolic Decompensation in a Noncompliant Child Detected Through Newborn Screening. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 2555–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Chen, P.; Yu, Z.; Yin, X.; Zhang, C.; Miao, H.; Huang, X. Newborn screening for 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency in Zhejiang province, China. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 542, 117266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, G.; Suormala, T.; Smit, G.P.A.; Reijngoud, D.-J.; Bink-Boelkens, M.T.E.; Niezen-Koning, K.E.; Baumgartner, E.R. 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency in an infant with cardiomyopathy, in her brother with developmental delay and in their asymptomatic father. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2000, 159, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünert, S.C.; Stucki, M.; Morscher, R.J.; Suormala, T.; Bürer, C.; Burda, P.; Christensen, E.; Ficicioglu, C.; Herwig, J.; Kölker, S.; et al. 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency: Clinical, biochemical, enzymatic and molecular studies in 88 individuals. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2012, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, R.; Vockley, C.W.; Edick, M.J.; Cameron, C.A.; Hiner, S.J.; Berry, S.A.; Vockley, J.; Arnold, G.L. Outcomes of cases with 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase (3-MCC) deficiency—Report from the Inborn Errors of Metabolism Information System. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2016, 118, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Wang, K.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Lin, Y. Newborn screening and genetic diagnosis of 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency in Quanzhou, China. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2024, 40, 101127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tluczek, A.; Ersig, A.L.; Lee, S. Psychosocial Issues Related to Newborn Screening: A Systematic Review and Synthesis. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLuca, J.M.; Kearney, M.H.; Norton, S.A.; Arnold, G.L. Parents’ Experiences of Expanded Newborn Screening Evaluations. Pediatrics 2011, 128, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botkin, J.R.; Rothwell, E.; Anderson, R.A.; Rose, N.C.; Dolan, S.M.; Kuppermann, M.; Stark, L.A.; Goldenberg, A.; Wong, B. Prenatal Education of Parents About Newborn Screening and Residual Dried Blood Spots: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazzorla, C.; Gragnaniello, V.; Gaiga, G.; Gueraldi, D.; Puma, A.; Loro, C.; Benetti, G.; Schiavo, R.; Porcù, E.; Burlina, A.P.; et al. Newborn Screening for Gaucher Disease: Parental Stress and Psychological Burden. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2025, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | Question (Rate from 1 to 10, Where 1 = Not at All, 10 = Very Much) |

|---|---|

| Q1 | How anxious did you feel after receiving the result of the newborn screening? |

| Q2 | How easy did you find it to understand the information you were given about the disease? |

| Q3 | How much emotional support did you feel you received from healthcare professionals? |

| Q4 | How often do you worry about your child’s future health due to the diagnosis? |

| Q5a | How much did the diagnosis initially affected your or your family daily life? |

| Q5b | How much does the diagnosis currently affect your or your family daily life? |

| Q6 | How useful do you think newborn screening for this disease has been in your experience? |

| Case | Sex | Ethnic Origin | NBS | Biochemical Phenotype | Genotype | Diagnosis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DBS C5OH (Cut off ≥0.80 µmol/L) | DBS C0 (nv > 11 µmol/L) | DBS C5OH (0.08–0.50 µmol/L) | Plasma Free Carnitine (29–42 µmol/L) | Urinary Organic Acids | Affected Gene | Nucleotide Change 1 | Nucleotide Change 2 | Amino Acid Change 1 | Amino Acid Change 2 | ||||

| P1 | M | Italy | 6.59 | 18.5 | 5.73 | 6.25 | 3-MCG, 3-HIVA | MCCC1 | c.189G>C | c.1331G>A | p.Arg63Ser | p.Arg444His | 3-MCCD |

| P2 | F | Italy | 5.32 | 28.9 | 3.18 | 25.6 | 3-MCG | MCCC2 | c.358A>T | c.436T>C | p.Ile120Phe | p.Tyr146His | 3-MCCD |

| P3 | M | Italy | 0.96 | 8.5 | 1.28 | 13.2 | 3-MCG, 3-HIVA | MCCC1 | c.230C>T | c.1526del | p.Ala77Val | p.Cys509Serfs*14 | 3-MCCD |

| P4 | M | Bangladesh | 2.6 | 33.4 | 2.91 | 32.8 | negative | MCCC2 | c.387T>C | c.903+5G>A | p.Ile133Thr | p.? | 3-MCCD |

| P5 | M | Italy | 1.21 | 13.2 | 1.98 | 31.1 | 3-MCG, 3-HIVA | MCCC1 | c.1194A>C | c.1594+1G>A | p.Glu383Asp | p.? | 3-MCCD |

| P6 | M | Morocco | 0.85 | 18.9 | 1.16 | 49.6 | 3-MCG, 3-HIVA | MCCC1 | c.1008G>C | c.1008G>C | p.Met336Ile | p.Met336Ile | 3-MCCD |

| P7 | F | Italy | 2.89 | 30.9 | 5.33 | 22.7 | 3-MCG, 3-HIVA | MCCC2 | c.295G>C | c.724G>T | p.Glu99Gln | p.Ala242Ser | 3-MCCD |

| P8 | M | Italy | 1.16 | 12.4 | 1.30 | 15.3 | 3-MCG, 3-HIVA | MCCC1 | c.230C>T | c.1526del | p.Ala77Val | p.Cys509Serfs*14 | 3-MCCD |

| P9 | F | Italy | 0.80 | 15.8 | 0.81 | 24.9 | negative | MCCC1 | c.1155A>C | / | p.Arg385Ser | / | 3-MCCD (Dominant negative allele) |

| E1 | M | Kosovo | 0.92 | 14.1 | 0.81 | 27.1 | negative | MCCC1 | c.725_727delATG | / | p.Asp242del | / | Healthy carrier |

| E2 | F | East Asia | 1.01 | 18 | 1.21 | 33.2 | negative | MCCC1 | c.863A>G | / | p.Glu288Gly | / | Healthy carrier |

| E3 | M | Moldova | 1.05 | 20.2 | 1.02 | 35.4 | negative | MCCC1 | c.1155A>C | / | p.Arg385Ser | / | Healthy carrier |

| E4 | M | Italy | 0.92 | 32 | 0.80 | 34.9 | negative | MCCC1 | c.414delT | / | p.Phe138Leufs*13 | / | Healthy carrier |

| E5 | F | Albania | 0.87 | 18.7 | 0.84 | 31.6 | negative | MCCC1 | c.288T>A | / | p.Tyr96* | / | Healthy carrier |

| E6 | M | Albania | 1.18 | 17 | 1.45 | 29.4 | negative | MCCC1 | c.1399A>T | / | p.Ile467Phe | / | Healthy carrier |

| N1 | F | Kosovo | 1.44 | 50.5 | 1.06 | 34.9 | negative | Negative | |||||

| N2 | M | Italy | 1.37 | 19.3 | 1.06 | 33.2 | negative | Negative | |||||

| N3 | F | Moldova | 1.08 | 34.6 | 0.9 | 40.9 | negative | Negative | |||||

| Clinical Phenotype/Outcome | Last Follow Up | Biochemical Parameters Before Carnitine Supplementation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Decompensation, Age | Growth and Development | Current Age (y) | DBS C5OH (0.08–0.50 µmol/L) | Plasma Free Carnitine (29–42 µmol/L) | Urinary Organic Acids | Diet | Medication | Age at Start Therapy | Plasma Free Carnitine (29–42 µmol/L) | |

| P1 | 1 yrs | Normal | 10 | 45.53 | 22.7 | 3MCG, 3HIVA | free | Carnitine 100 mg/kg | At birth | 6.25 |

| P2 | No | Developmental delay (transient) | 10 | 9.70 | 23.3 | 3MCG, 3HIVA | free | Carnitine 100 mg/kg | 2 yrs | 8.4 |

| P3 | No | No | 7 | 4.4 | 29.9 | 3HIVA, 3MCG | free | no | / | / |

| P4 | No | No | 3 | 7.98 | 14 | 3HIVA, 3MCG | free | no | 3 yrs | / |

| P5 | No | No | 2 | 5.89 | 44.4 | 3MCG, 3HIVA | free | Carnitine 100 mg/kg | 3 mos | 9.3 |

| P6 | No | No | 2 | 1.71 | 20.7 | 3MCG, 3HIVA | free | no | / | / |

| P7 * | No | Growth retardation | 2 | 9.56 | 20.3 | 3MCG, 3HIVA | free | Carnitine 100 mg/kg | 1 yr | 6.3 |

| P8 | No | No | 1 | 2.29 | 33.1 | 3MCG, 3HIVA | free | no | / | / |

| P9 | No | No | 1 | 1.07 | 497 | 3MCG, 3HIVA | free | no | / | / |

| Fathers (n = 8) | Mothers (n = 6) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Median | p-Value | |

| Question 1 | 7.5 | 10 | 0.02 * |

| Question 2 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 0.89 |

| Question 3 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 0.79 |

| Question 4 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 0.22 |

| Question 5a | 4.5 | 7.5 | 0.20 |

| Question 5b | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.52 |

| Question 6 | 8.0 | 10 | 0.02 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Neonatal Screening. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gragnaniello, V.; Gaiga, G.; Cazzorla, C.; Porcù, E.; Gueraldi, D.; Puma, A.; Loro, C.; Doimo, M.; Salviati, L.; Burlina, A.B. Psychological Impact of Newborn Screening for 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA Carboxylase Deficiency: The Parental Experience. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2025, 11, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11040115

Gragnaniello V, Gaiga G, Cazzorla C, Porcù E, Gueraldi D, Puma A, Loro C, Doimo M, Salviati L, Burlina AB. Psychological Impact of Newborn Screening for 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA Carboxylase Deficiency: The Parental Experience. International Journal of Neonatal Screening. 2025; 11(4):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11040115

Chicago/Turabian StyleGragnaniello, Vincenza, Giacomo Gaiga, Chiara Cazzorla, Elena Porcù, Daniela Gueraldi, Andrea Puma, Christian Loro, Mara Doimo, Leonardo Salviati, and Alberto B. Burlina. 2025. "Psychological Impact of Newborn Screening for 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA Carboxylase Deficiency: The Parental Experience" International Journal of Neonatal Screening 11, no. 4: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11040115

APA StyleGragnaniello, V., Gaiga, G., Cazzorla, C., Porcù, E., Gueraldi, D., Puma, A., Loro, C., Doimo, M., Salviati, L., & Burlina, A. B. (2025). Psychological Impact of Newborn Screening for 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA Carboxylase Deficiency: The Parental Experience. International Journal of Neonatal Screening, 11(4), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11040115