Learning Collaborative to Support Continuous Quality Improvement in Newborn Screening

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Assess needs and engage state and territorial NBS programs for participation in a multidisciplinary collaborative network focused on NBS quality improvement projects.

- Coordinate and facilitate QI projects and data-driven outcome assessments, utilizing evidence-based QI methodologies within each participating state/jurisdiction NBS program.

- Create a model for replication, sharing, and sustainability of NBS QI projects.

2. Materials and Methods

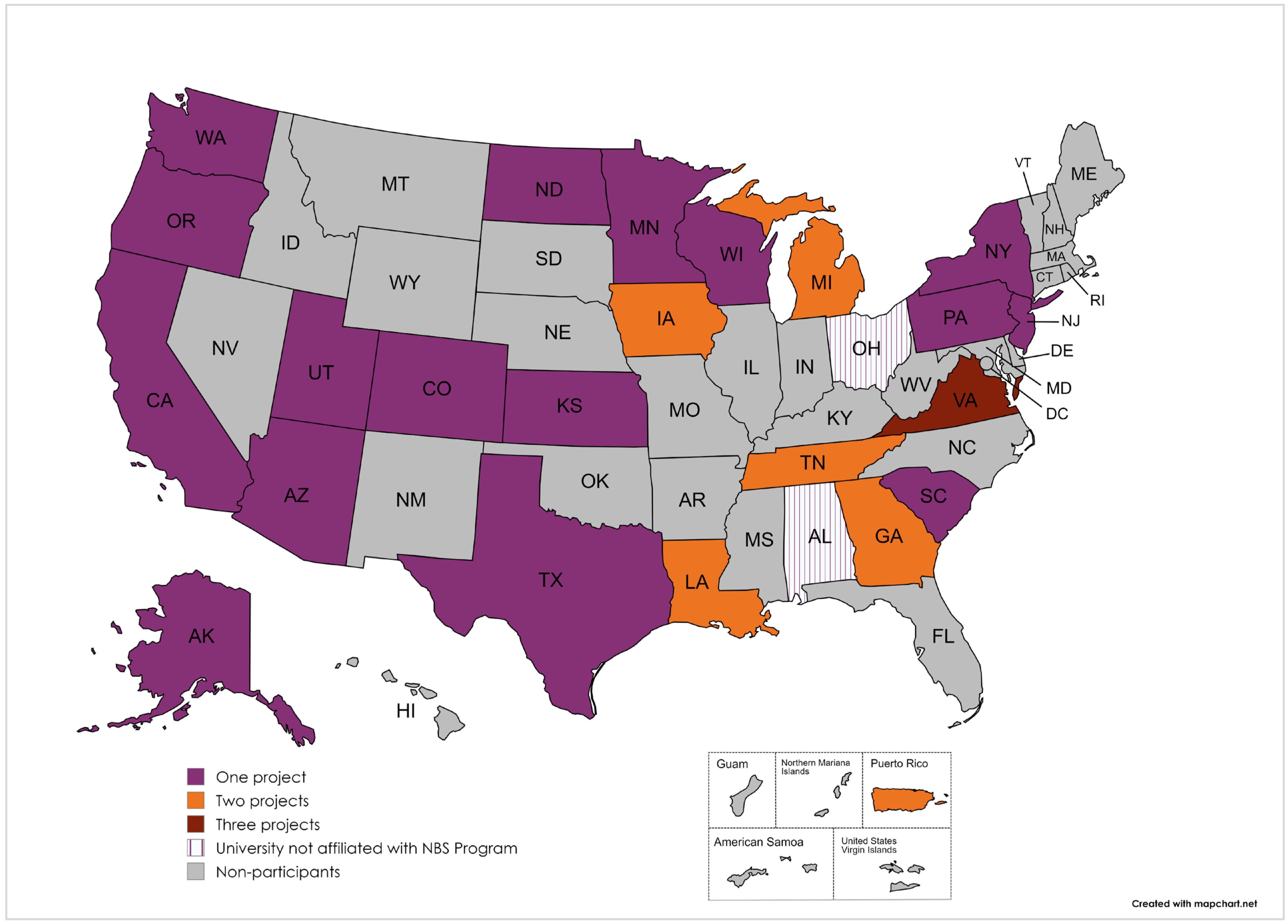

2.1. Collaborative Formation and Criteria for Participant Inclusion

- Project Data- well-defined problem and plans for collecting baseline data and measuring data

- Project Charter/Action Plan- change ideas specified, project team members representing the NBS system identified with project roles defined, and demonstration of staff and leadership support

- Budget/Justification- funding needs and how they relate to the goals and objectives of the project

- Impact- why the project is important, how it will improve the NBS system/community served

- Sustainability- how activities will be sustained upon completion of the funding cycle

2.2. QI Collaborative Engagement and Activities

2.3. Evaluation Criteria for QI Collaborative

3. Results

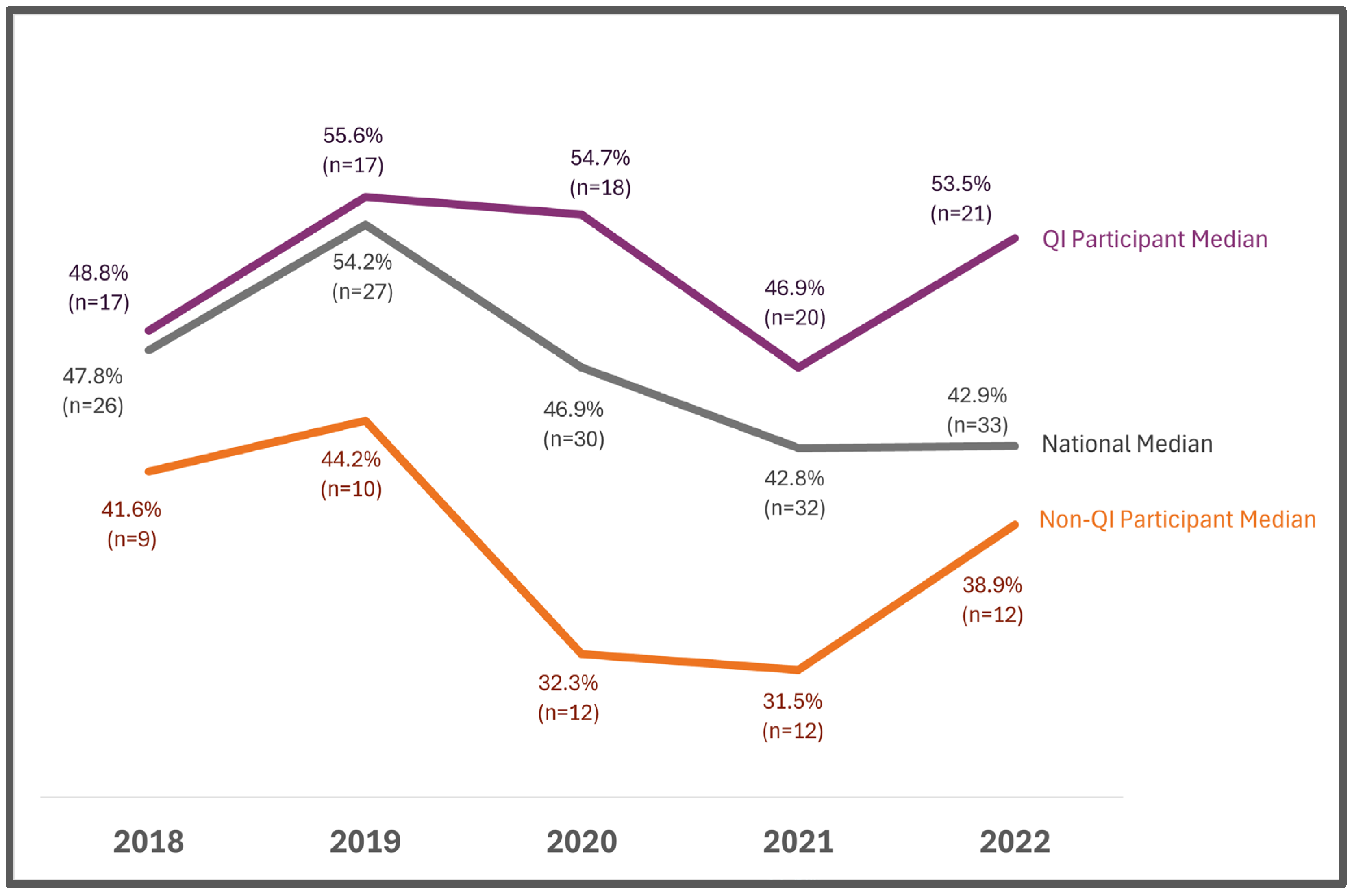

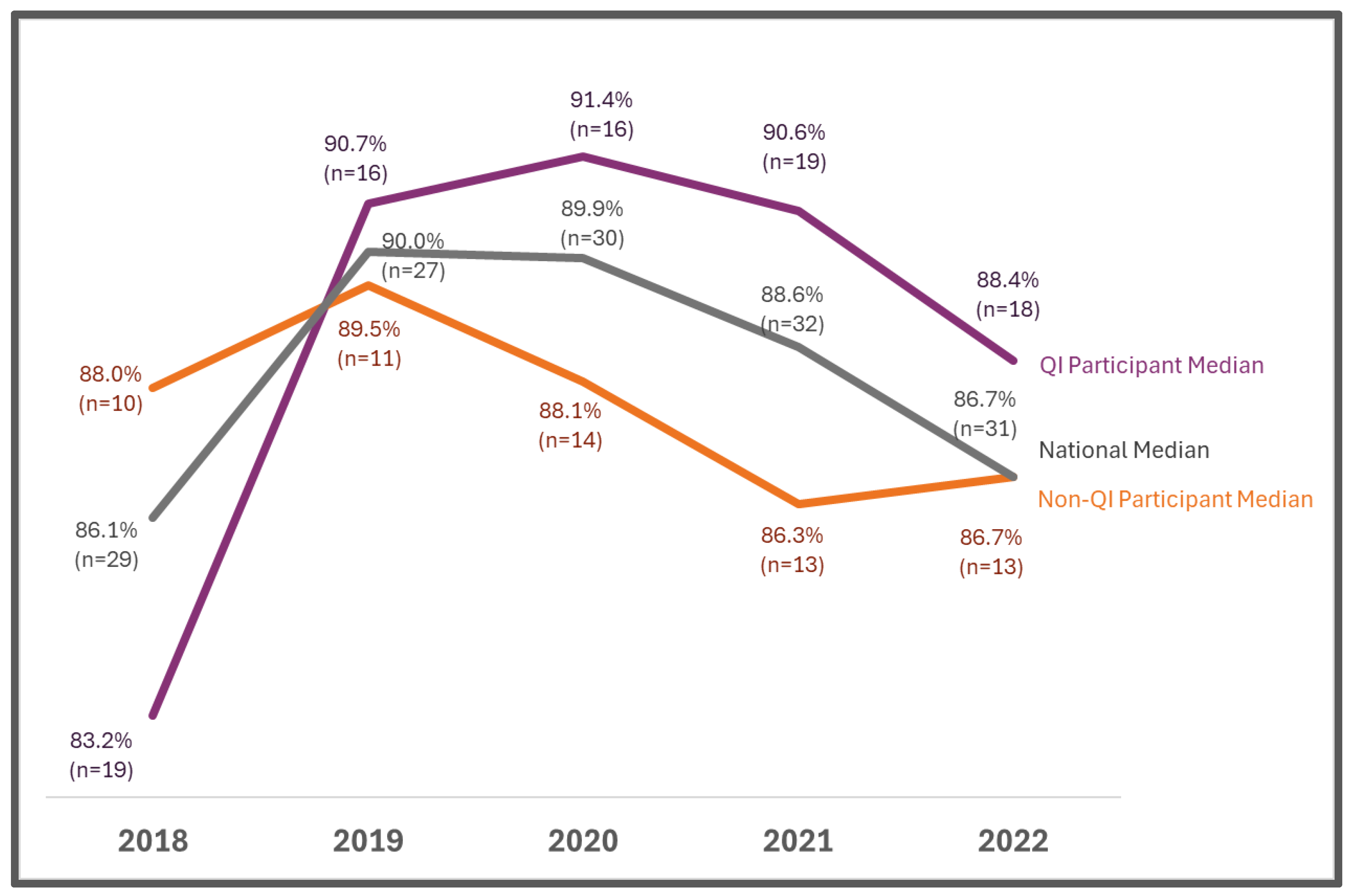

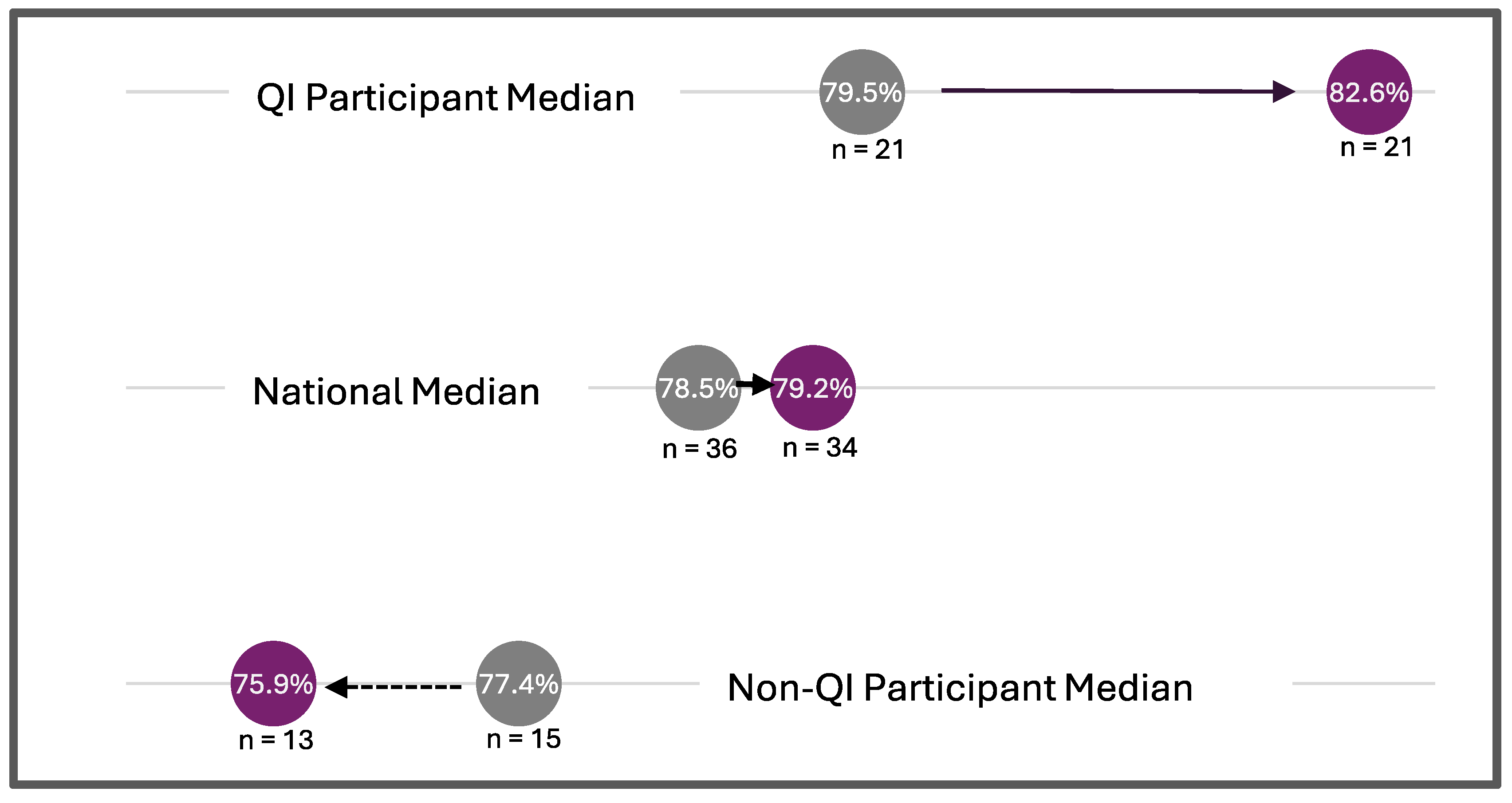

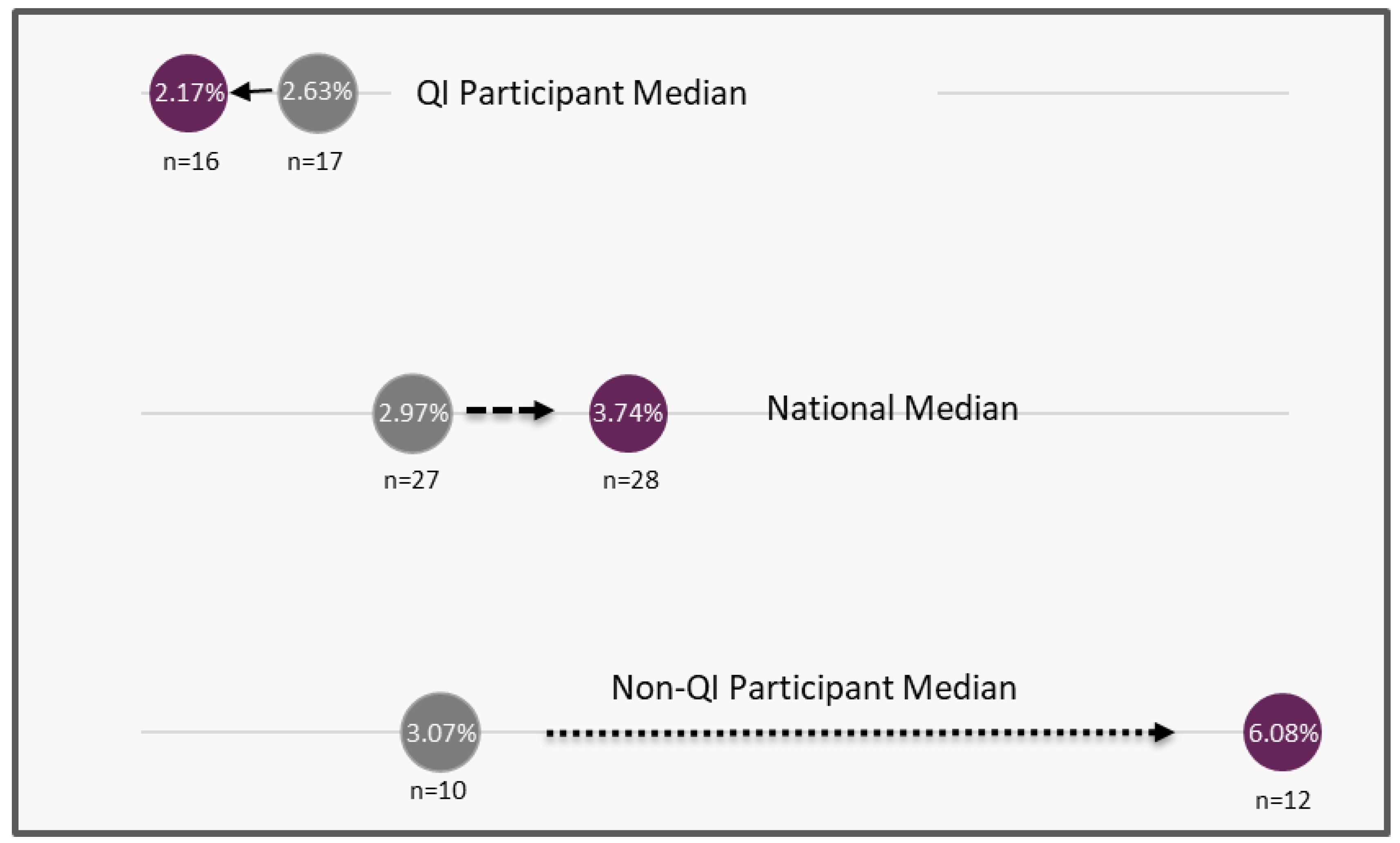

3.1. Quality Improvement Metrics

3.2. Program Evaluation

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Strengths

4.3. Challenges

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Impact

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| Webinar Topic | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Awardee Kickoff Call | November 2019 | Introduction and overview of the QI Projects Collaborative (Cohort 1) |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Cohort 1 Webinar | January 2020 | Tools and strategies for starting a continuous quality improvement project |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Cohort 2 Kick-off Call | April 2020 | Introduction and overview of the QI Projects Collaborative (Cohort 2) |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Teach and Learn, Steel Shamelessly, Share Seamlessly | June 2020 | Introduction to relational coordination and strategies for building collaborative relationships to achieve project goals |

| NewSTEPs CQI National Webinar: So, You Want to Start a Quality Improvement Project | July 2020 | Strategies for identifying a strong aim statement, ways to gain organizational buy-in, and techniques for testing change and measuring impact |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Introduction to Measuring and Interpreting Quality Improvement Data: Introduction to Run Charts | September 2020 | Introduction to run charts and tracking improvement |

| NewSTEPs CQI National Webinar: Tools for Tracking and Measuring Improvement | October 2020 | Introduction to a suite of tools templates, and software for designing charts and diagrams useful for tracking and measuring improvement including process maps, run charts, and control charts |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Introduction to Measuring and Interpreting QI Data: Run Charts, a Deeper Dive | November 2020 | Introduction to building and interpreting run charts |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Improvement Burnout and the Power of Small Wins | January 2021 | Introduction to quality improvement burnout and how to avoid it by taking the time to celebrate small wins |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Celebrating Successes and Strategies for Holding the Gains | March 2021 | A continuation of the celebration of small wins and strategies for sustaining project successes |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Cohort 3 Kick-off Call | April 2021 | Introduction and overview of the QI Projects Collaborative (Cohort 3) |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Introduction to the Change Package | June 2021 | Strategies for gaining or increasing buy-in to advance improvements within quality improvement projects |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Getting Buy-In to Advance Improvement | October 2021 | Strategies for gaining or increasing buy-in to advance improvements within quality improvement projects |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Cohort 4 Kick-Off Call | February 2021 | Introduction and overview of the QI Projects Collaborative (Cohort 4) |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Tools for Every Stage of the PDSA | April 2022 | Outline specific tools available at each stage of the Plan-Do-Study-Act to assist teams when performing rapid cycle testing and PDSA tracking strategies |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Strategies for Defining the Problem | June 2022 | Ideas to systematically define a problem and identify a possible change idea |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: Sustaining Momentum | September 2022 | Approaches to maintain impetus as QI project continues; NewSTEPs repository visualizations utility in QI work shared |

| NewSTEPs QI Projects: NBS Collection Device Modification | December 2022 | Demonstration of how to use quality improvement tools when changing the newborn screening collection device and what quality control measures to monitor |

| Variation Knowledge: Understanding and Managing Variation to Improve Outcomes | March 2023 | Review independent system fundamentals crucial to improving the performance of systems; distinguish between variation types to respond to improvement |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ten great public health achievements—Worldwide, 2001–2010. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2011, 60, 814–818. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Public Health Laboratories NewSTEPs Data Center. Available online: https://www.newsteps.org/data-resources (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Ojodu, J.; Singh, S.; Kellar-Guenther, Y.; Yusuf, C.; Jones, E.; Wood, T.; Baker, M.; Sontag, M.K. NewSTEPs: The Establishment of a National Newborn Screening Technical Assistance Resource Center. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2018, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, D.B., Jr.; Gehtland, L. Newborn screening: Evolving challenges in an era of rapid discovery. JAMA 2015, 313, 1511–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The Breakthrough Series: IHI’s Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement. 2003. Available online: https://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/TheBreakthroughSeriesIHIsCollaborativeModelforAchievingBreakthroughImprovement.aspx (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Langley, G.J.; Moen, R.D.; Nolan, K.M.; Nolan, T.W.; Norman, C.L.; Provost, L.P. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance, 2nd ed.; Jossey Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, B.; Gupta, V. Continuous Quality Improvement. Updated 5 April 2022. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559239/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Gorenflo, G. Journey to a Quality Improvement Culture. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2011, 17, 472–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, C.; Sontag, M.K.; Miller, J.; Kellar-Guenther, Y.; McKasson, S.; Shone, S.; Singh, S.; Ojodu, J. Development of National Newborn Screening Quality Indicators in the United States. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2019, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quality Indicators|NewSTEPs. APHL. 2023. Available online: https://www.newsteps.org/data-center/quality-indicators?q=data-resources/quality-indicators (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) & TalentLMS. 2022 Workplace Learning & Development Trends: Executive Summary. 2022. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/content/dam/en/shrm/research/2022-Workplace-Learning-and-Development-Trends-Report.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

| Project Category | Barriers |

|---|---|

| Timeliness |

|

| Identification and Follow-up of Out-of-Range Results |

|

| Communication of NBS results to providers/parents |

|

| Diagnosis Confirmation |

|

| Emerging Issues |

|

| Quality Indicator [10] | Subcategory |

|---|---|

| Unsatisfactory Specimens |

|

| Unsatisfactory Specimens |

|

| Missing Essential Information | Percent of dried blood spot specimens with at least one missing state-defined essential data field upon receipt at the laboratory |

| Unscreened Newborns | Percent of newborns without a valid dried blood spot newborn screen |

| Lost To Follow-Up |

|

| Lost To Follow-Up |

|

| Lost To Follow-Up |

|

| Timeliness |

|

| Timeliness |

|

| Timeliness |

|

| Timeliness |

|

| State Project Team | Years Involved | Project Type | Result As It Relates to Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 2020–2021 | Timeliness | Unsatisfactory specimen rate improved |

| California | 2020–2023 | Timeliness | Transit time improved |

| Colorado | 2019–2021 | Timeliness | Did not reach goal |

| Georgia 2 | 2019–2021 | Timeliness | Unsatisfactory specimen rate improved |

| Kansas | 2020–2023 | Timeliness | Transit time improved |

| Louisiana 1 | 2019–2024 | Timeliness | Time to result reporting improved |

| Louisiana 2 | 2020–2021 | Timeliness | QI model implemented |

| New Jersey | 2021–2023 | Timeliness | Transit time improved for pilot participants |

| New York | 2019–2024 | Timeliness | Transit time improved |

| Oregon | 2022 | Timeliness | Transit time improved |

| Pennsylvania | 2020–2021 | Timeliness | Time to result reporting improved |

| Puerto Rico 1 | 2019–2024 | Timeliness | Time to result reporting improved |

| Puerto Rico 2 | 2019–2024 | Timeliness | Time to result reporting improved |

| South Carolina | 2019–2024 | Timeliness | Transit time improved |

| Tennessee 1 | 2019–2022 | Timeliness | Time to result reporting improved |

| Texas | 2021–2024 | Timeliness | Did not reach goal |

| Virginia 1 | 2019–2024 | Timeliness | Time to result reporting improved and decreased missing essential data |

| Virginia 2 | 2020–2023 | Timeliness | Time to result reporting improved |

| Washington | 2021–2022 | Timeliness | Transit time improved |

| Wisconsin | 2020–2021 | Timeliness | Time to result reporting improved |

| Georgia 1 | 2019–2021 | Identification of out-of-range results | Positive predictive value for specific disorders improved |

| Tennessee 2 | 2021–2022 | Identification of out-of-range results | Positive predictive value for specific disorders improved |

| Utah | 2021–2024 | Identification of out-of-range results | Did not reach goal |

| Iowa 1 | 2019–2022 | Communication of results | Did not reach goal |

| Michigan 1 | 2021–2022 | Communication of results | Parental awareness of NBS improved |

| Michigan 2 | 2022–2023 | Communication of results | Midwife reporting rates improved |

| Minnesota | 2019–2023 | Communication of results | Long-term follow-up improved |

| North Dakota | 2020–2022 | Communication of results | Long-term follow-up improved |

| Univ of Alabama at Birmingham | 2021–2024 | Communication of results | Documented Sickle Cell Disorder follow-up practices across states |

| Alaska | 2019–2021 | Confirming diagnosis | Critical Congenital Heart Disease detection rates determined |

| Cincinnati Children’s | 2021–2024 | Confirming diagnosis | Did not reach goal |

| Iowa 2 | 2021–2022 | Emerging issues | Developed an enhanced continuity of operations plan |

| Virginia 3 | 2021–2023 | Emerging issues | Developed an enhanced continuity of operations plan |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Neonatal Screening. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jones, E.; Singh, S.; McKasson, S.; Sheller, R.; Ojodu, J.; Comer, A. Learning Collaborative to Support Continuous Quality Improvement in Newborn Screening. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2025, 11, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030070

Jones E, Singh S, McKasson S, Sheller R, Ojodu J, Comer A. Learning Collaborative to Support Continuous Quality Improvement in Newborn Screening. International Journal of Neonatal Screening. 2025; 11(3):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030070

Chicago/Turabian StyleJones, Elizabeth, Sikha Singh, Sarah McKasson, Ruthanne Sheller, Jelili Ojodu, and Ashley Comer. 2025. "Learning Collaborative to Support Continuous Quality Improvement in Newborn Screening" International Journal of Neonatal Screening 11, no. 3: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030070

APA StyleJones, E., Singh, S., McKasson, S., Sheller, R., Ojodu, J., & Comer, A. (2025). Learning Collaborative to Support Continuous Quality Improvement in Newborn Screening. International Journal of Neonatal Screening, 11(3), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030070