Evaluation of Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening and Follow-Up Process in Georgia (2022–2023)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Birth Data

3.2. New Cases of Cystic Fibrosis

3.3. Specific Mutations in Georgia

4. Discussion

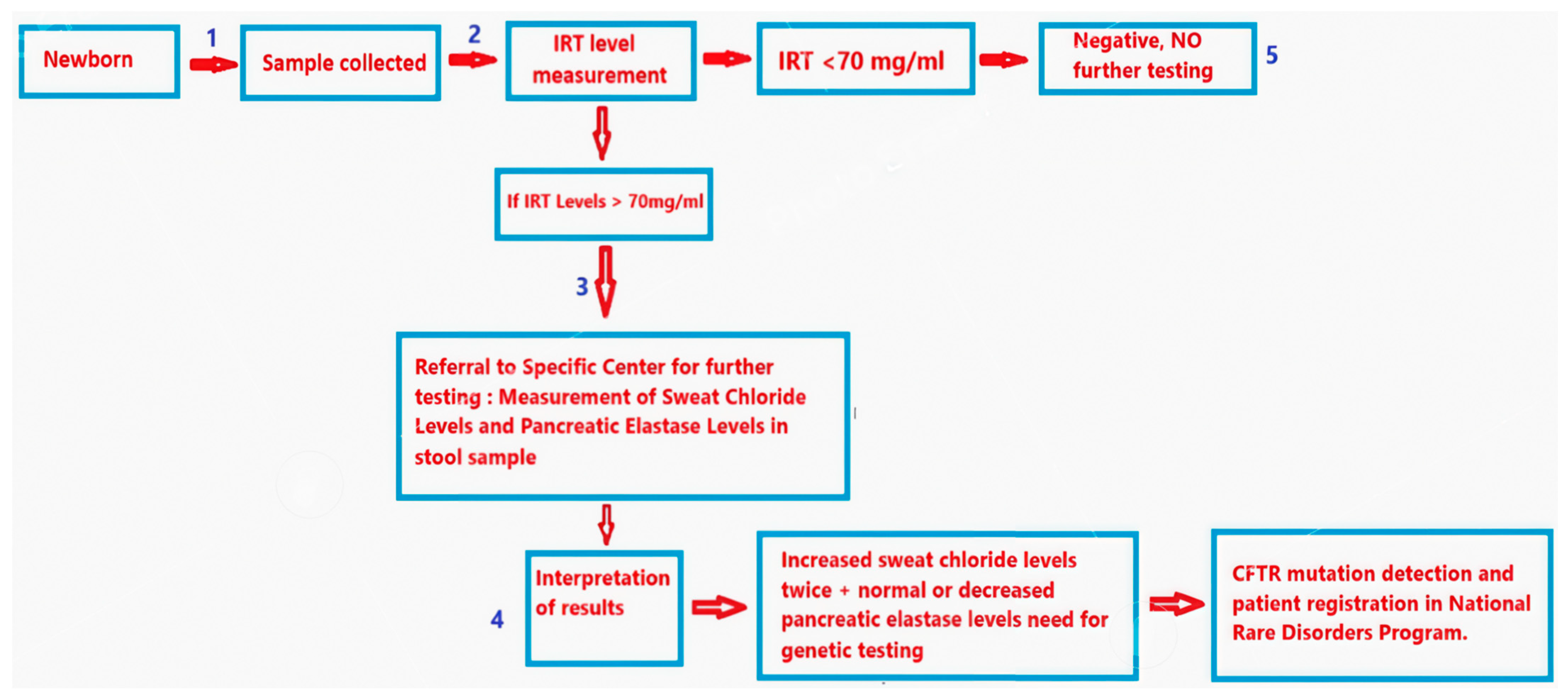

Theoretically, our national CF NBS program, with IRT determination followed by additional testing (sweat chloride and pancreatic elastase) provides an efficient means for detecting or excluding the diagnosis of CF, but multiple challenges exist. The IRT determination is five times cheaper than the IRT-DNA protocol. Genetic testing can take up to a month with our current capacity in Georgia. But having the screen positive for initial elevated IRT, without further identifying these infants for the additional testing becomes problematic.

- A blood sample should be collected within 48–72 h of birth. Missed cases may occur if one of the following happens:

- (a)

- The sample was not taken or sent to the lab.

- (b)

- The sample was not taken within the recommended time frame, especially if the patient was discharged before they were 24 h old.

- (c)

- The newborn was not fed enterally, leading to false negative IRT levels.

- (d)

- The blood sample was not properly labeled with the patient’s name and surname.

- Samples sent to screening lab.

- A monitoring system is lacking in the government, screening lab, or rare disorders center to ensure patients with elevated IRT levels are referred for sweat chloride testing. As noted in our article, this gap is a key factor in missed diagnoses, as the rare disorders center only received the results after the patient came for additional testing.

- Normal results: Sweat chloride <29 mmol/L and pancreatic elastase >200 mcg/g. Abnormal results: (a) Sweat chloride >29 mmol/L and elastase >200 mcg/g require the monitoring of chloride levels. If they decrease on retesting, the diagnosis is excluded. (b) Sweat chloride <29 mmol/L and elastase <200 mcg/g call for the initiation of enzyme treatment and monitoring of elastase levels. If there is no response, further tests are conducted to identify the cause of pancreatic insufficiency. (c) Sweat chloride >29 mmol/L and elastase <200 mcg/g indicate high risk for the disease. The sweat chloride test is repeated and genetic testing is performed if levels remain elevated.

- In the Georgian protocol, if a patient has normal sweat chloride and pancreatic elastase levels within their first month of life, a second sweat chloride test is recommended at 4 months to double-check and exclude the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kerem, B.; Rommens, J.M.; Buchanan, J.A.; Markiewicz, D.; Cox, T.K.; Chakravarti, A.; Buchwald, M.; Tsui, L.C. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene. Science 1990, 245, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riordan, J.R.; Rommens, J.M.; Kerem, B.-S.; Alon, N.; Rozmahel, R.; Grzelczak, Z.; Zielenski, J.; Lok, S.; Plavsic, N.; Chou, J.-L.; et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: Cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science 1989, 245, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutting, G.R. Cystic fibrosis genetics: From molecular understanding to clinical application. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 16, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, A. Cystic fibrosis: A review of pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2021, 14, 1120–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry Report; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Quinton, P.M. Cystic fibrosis: A disease of the CFTR ion channel. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2008, 70, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cono, J.; Farrell, P.M.; Hannon, W.H.; Khoury, M.J.; Qualls, N.L. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: A global perspective. Pediatrics 1997, 99, 411–412. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, M.R.; Clarke, L.L.; Drumm, M.L.; Yankaskas, J.R.; Boucher, R.C.; Button, B.; Davis, S.D.; Flume, P.A.; Gibson, R.L.; Konstan, M.W.; et al. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 2019, 394, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, P.M. Why cystic fibrosis newborn screening programs have failed to meet original expectations… thus far. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2023, 140, 107679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotet, V.; Gutierrez, H.; Farrell, P.M. NBS for CF across the Globe—Where Is It Worthwhile? Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, P.M.; White, T.B.; Ren, C.L.; Hempstead, S.E.; Accurso, F.; Derichs, N.; Howenstine, M.; McColley, S.A.; Rock, M.; Rosenfeld, M.; et al. Diagnosis of cystic fibrosis: Consensus guidelines from the cystic fibrosis foundation. J. Pediatr. 2017, 181, S4–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurtsilava, I.; Agladze, D.; Parulava, T.; Margvelashvili, L.; Kvlividze, O. Specifics of cystic fibrosis genetic spectrum in Georgia. Int. J. Internet Res. 2023, 8, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CFTR2 Database. CFTR Mutations and Disease Severity. Available online: http://cftr2.org (accessed on 10 January 2025).

| 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|

| Live Births | 40,420 | 37,695 |

| Increased IRT | 768 (1.9%) | 645 (1.7%) |

| Follow-Up Chloride Test | 460 (59.9%) | 330 (51.2%) |

| Elevated Chloride | 62 (13.5%) | 37 (11.2%) |

| New CF Cases (Late Diagnosis) | 8 (2) | 10 (1) |

| Incidence Rate | 1 in 5051 newborns | 1 in 3774 newborns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Neonatal Screening. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vardosanidze, N.; Kavlashvili, N.; Margvelashvili, L.; Kvlividze, O.; Diakonidze, M.; Iordanishvili, S.; Agladze, D. Evaluation of Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening and Follow-Up Process in Georgia (2022–2023). Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2025, 11, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11020043

Vardosanidze N, Kavlashvili N, Margvelashvili L, Kvlividze O, Diakonidze M, Iordanishvili S, Agladze D. Evaluation of Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening and Follow-Up Process in Georgia (2022–2023). International Journal of Neonatal Screening. 2025; 11(2):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11020043

Chicago/Turabian StyleVardosanidze, Nino, Nani Kavlashvili, Lali Margvelashvili, Oleg Kvlividze, Mikheil Diakonidze, Saba Iordanishvili, and Dodo Agladze. 2025. "Evaluation of Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening and Follow-Up Process in Georgia (2022–2023)" International Journal of Neonatal Screening 11, no. 2: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11020043

APA StyleVardosanidze, N., Kavlashvili, N., Margvelashvili, L., Kvlividze, O., Diakonidze, M., Iordanishvili, S., & Agladze, D. (2025). Evaluation of Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening and Follow-Up Process in Georgia (2022–2023). International Journal of Neonatal Screening, 11(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11020043