Screening Blind Spot: Missing Preterm Infants in the Detection of Congenital Hypothyroidism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aotearoa New Zealand Newborn Metabolic Screening Process for Low Birth Weight Infants (<1500 g) During Audit Timeframe

2.2. Audit Methodology

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

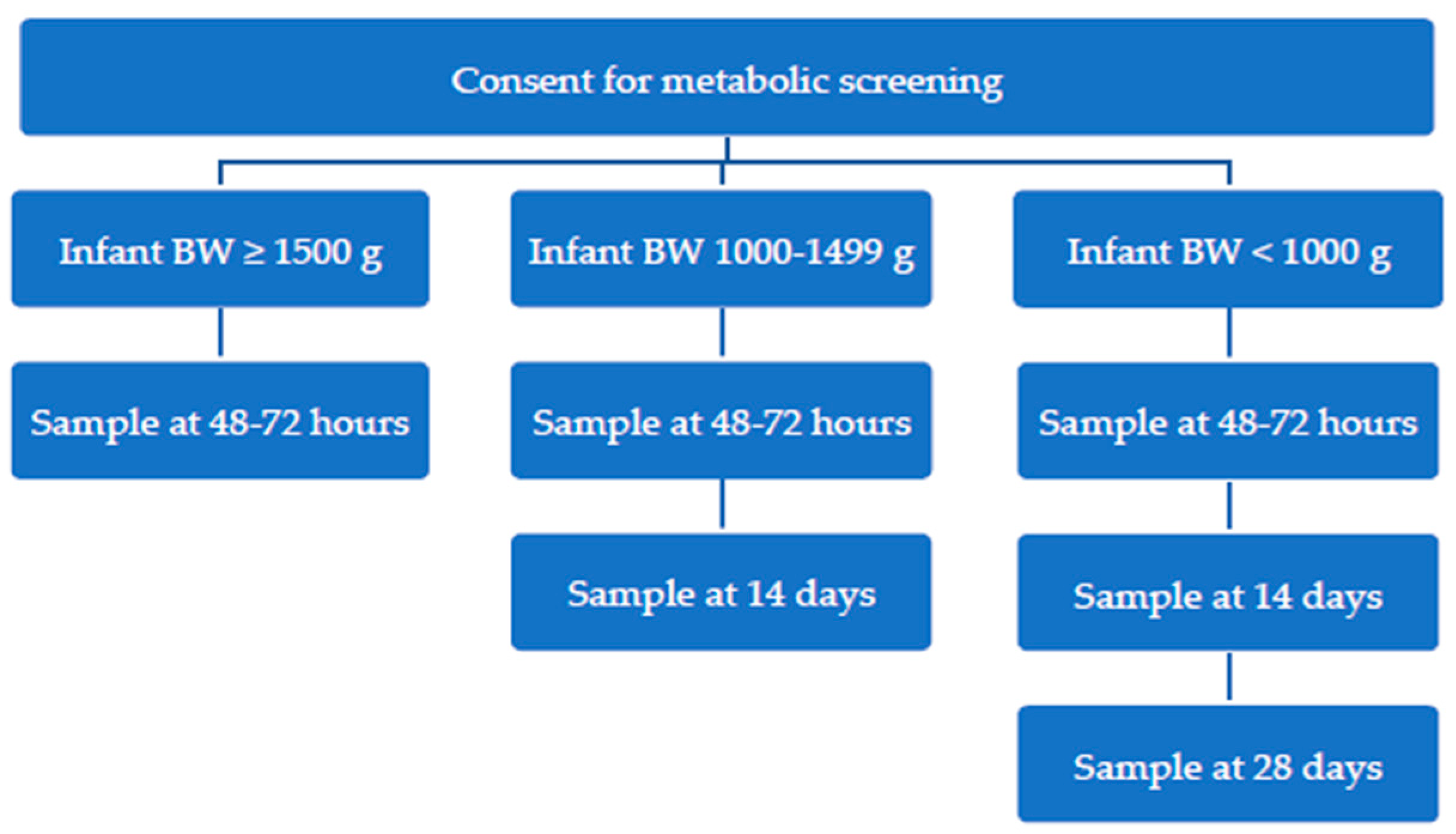

New ‘Preterm Metabolic Bloodspot Screening Protocol

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ford, G.; LaFranchi, S.H. Screening for congenital hypothyroidism: A worldwide view of strategies. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 28, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, T.; Greaves, R.; Mawad, N.; Greed, L.; Wotton, T.; Wiley, V.; Ranieri, E.; Rankin, W.; Ungerer, J.; Price, R.; et al. Fifty years of newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism: Current status in Australasia and the case for harmonisation. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2022, 60, 1551–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Screening Unit. Newborn Metabolic Screening Programme Annual Report 2021; Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2023.

- Woo, H.C.; Lizarda, A.; Tucker, R.; Mitchell, M.L.; Vohr, B.; Oh, W.; Phornphutkul, C. Congenital hypothyroidism with a delayed thyroid-stimulating hormone elevation in very premature infants: Incidence and growth and developmental outcomes. J. Pediatr. 2011, 158, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijarnia, S.; Wilcken, B.; Wiley, V.C. Newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism in very-low-birth-weight babies: The need for a second test. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011, 34, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, B.B.; Cutfield, W.S.; Webster, D.; Carll, J.; Derraik, J.G.B.; Jefferies, C.; Gunn, A.J.; Hofman, P.L. Etiology of increasing incidence of congenital hypothyroidism in New Zealand from 1993–2010. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 3155–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, N.; Hawkes, C.P.; Mayne, P.; Murphy, N.P. Optimal Timing of Repeat Newborn Screening for Congenital Hypothyroidism in Preterm Infants to Detect Delayed Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Elevation. J. Pediatr. 2019, 205, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFranchi, S.H. Thyroid Function in Preterm/Low Birth Weight Infants: Impact on Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Dysfunction. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 666207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger, J.; Olivieri, A.; Donaldson, M.; Torresani, T.; Krude, H.; van Vliet, G.; Polak, M.; Butler, G.; ESPE-PES-SLEP-JSPE-APEG-APPES-ISPAE; Congenital Hypothyroidism Consensus Conference Group. European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology consensus guidelines on screening, diagnosis, and management of congenital hypothyroidism. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2014, 81, 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J.; LaFranchi, S.H. Fetal and neonatal thyroid function: Review and summary of significant new findings. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2010, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, S.; Saenz-Rico, B.; Arnaez, J.; Diez-Sebastian, J.; Omeñaca, F.; Bernal, J. Effects of oral iodine supplementation in very low birth weight preterm infants for the prevention of thyroid function alterations during the neonatal period: Results of a randomised assessor-blinded pilot trial and neurodevelopmental outcomes at 24 months. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Zealand Ministry of Health. Report on Maternity Web Tool. Available online: https://tewhatuora.shinyapps.io/report-on-maternity-web-tool/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Chow, S.S.W.; Creighton, P.; Chambers, G.M.; Lui, K. Report of the Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network 2020; ANZNN: Sydney, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics New Zealand. 2018 Census Place Summaries. Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/2018-census-place-summaries/new-zealand (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Kaluarachchi, D.C.; Allen, D.B.; Eickhoff, J.C.; Dawe, S.J.; Baker, M.W. Increased Congenital Hypothyroidism Detection in Preterm Infants with Serial Newborn Screening. J. Pediatr. 2019, 207, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odenwald, B.; Fischer, A.; Röschinger, W.; Liebl, B. Long-term course of hypothyroidism detected through neonatal TSH screening in a population-based cohort of very preterm infants born at less than 32 weeks of gestation. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2021, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Screening Unit. Guidelines for Practitioners Providing Services Within the Newborn Metabolic Screening Programme in New Zealand; National Screening Unit: Wellington, New Zealand, 2010.

- CLSI. Newborn Screening for Congenital Hypothyroidism; First Edition Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Berwyn, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics New Zealand. Live Births by Area, Regional Councils (Maori and Total Population) (Annual-Dec); Statistics New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2019.

- Kaluarachchi, D.C.; Allen, D.B.; Eickhoff, J.C.; Dawe, S.J.; Baker, M.W. Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Reference Ranges for Preterm Infants. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20190290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, R.F.; Northfield, J.-A.; Cross, L.; Mawad, N.; Nguyen, T.; Tan, M.; O’Connell, M.A.; Pitt, J. Managing newborn screening repeat collections for sick and preterm neonates. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2024, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigone, M.C.; Caiulo, S.; Di Frenna, M.; Ghirardello, S.; Corbetta, C.; Mosca, F.; Weber, G. Evolution of thyroid function in preterm infants detected by screening for congenital hypothyroidism. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Provincial Health Services Authority (PHSA). Neonatal Guideline: Newborn Metabolic Screening; Perinatal Services BC: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. PHE Screening. In Guidelines for Newborn Blood Spot Sampling; Public Health England: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Minamitani, K. Newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism in Japan. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2021, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M.A.; Rodd, C.; Dussault, J.H.; Van Vliet, G. Very low birth weight newborns do not need repeat screening for congenital hypothyroidism. J. Pediatr. 2002, 140, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B.; Lee, K. Head size and growth in the very preterm infant: A literature review. Res. Rep. Neonatol. 2015, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selva, K.A.; Harper, A.; Downs, A.; Blasco, P.A.; Lafranchi, S.H. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in congenital hypothyroidism: Comparison of initial T4 dose and time to reach target T4 and TSH. J. Pediatr. 2005, 147, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.M.; O’Shea, T.M.; Allred, E.N.; Heeren, T.; Hirtz, D.; Jara, H.; Leviton, A.; Kuban, K.C.K.; ELGAN Study Investigators. Neurocognitive and Academic Outcomes at Age 10 Years of Extremely Preterm Newborns. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20154343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Newborn Screening for Preterm, Low Birth Weight, and Sick Newborns; Approved Guideline CLSI Document NBS03-A; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, S.R.; Wassner, A.J.; Wintergerst, K.A.; Yayah-Jones, N.-H.; Hopkin, R.J.; Chuang, J.; Smith, J.R.; Abell, K.; LaFranchi, S.H.; Section on Endocrinology Executive Committee; et al. Congenital Hypothyroidism: Screening and Management. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022060420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heather, N.; de Hora, M.; Brothers, S.; Grainger, P.; Knoll, D.; Webster, D. Introducing Newborn Screening for Severe Combined Immunodeficiency—The New Zealand Experience. Screening 2022, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Hora, M.R.; Heather, N.L.; Webster, D.R.; Albert, B.B.; Hofman, P.L. Evaluation of a New Laboratory Protocol for Newborn Screening for Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia in New Zealand. Screening 2022, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Hora, M.R.; Heather, N.L.; Patel, T.; Bresnahan, L.G.; Webster, D.; Hofman, P.L. Implementing steroid profiling by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry improves newborn screening for congenital adrenal hyperplasia in New Zealand. Clin. Endocrinol. 2021, 94, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protocol prior to 1 January 2013: | |

| TSH < 15 mIU/L = Normal TSH ≥ 15 mIU/L = Follow-up specimen required | |

| Protocol from 1 January 2013: | |

| Age ≤ 14 days: | TSH < 15 mIU/L = Normal TSH ≥ 15 mIU/L = Follow-up specimen required |

| Age > 14 days: | TSH < 8 mIU/L = Normal TSH ≥ 8 mIU/L = Follow-up specimen required |

| Sex | Gestational Age at Birth | Birth Weight (g) | Ethnicity | Screen Positive Sample | Reason for Thyroid Function Tests | Age at Diagnosis | Screening Whole Blood TSH (mIU/L) | At Diagnosis | Outcome (Permanent, Transient) | Age Ceased Thyroxine | Co-Morbidities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Weeks + Days) | Serum TSH (mU/L) Ref: 0.4–16 mU/L | Serum Free T4 (pmol/L) Ref: 10–40 pmol/L | ||||||||||

| Clinically detected | ||||||||||||

| Male | 28 + 3 | 830 | Samoan | Fourth | Third screen borderline for amino acid breakdown disorder, fourth sample requested | 6 weeks | 8 | 18.2 | 17 | Transient | 2 years | Very preterm, ambiguous genitalia with imperforate anus, ELBW, Apnoea of prematurity, RDS, jaundice |

| Male | 28 + 3 | 1350 | Samoan | Third | Unscheduled third screening sample | 5 weeks | 18 | 33 | 6.2 | Transient | 2 years | Very premature, RDS, Apnoea of Prematurity, RoP |

| Female | 29 | 980 | New Zealand European | Maternal Hypothyroidism | 6 weeks | 39 | 12.5 | Transient | 2 years | Very preterm, RoP, AOP, RDS, jaundice, | ||

| Male | 30 | 1600 | Chinese | Feeding problems | 12 weeks | 11.9 | 14 | Transient | 18 months | Very preterm | ||

| Male | 31 | 1490 | Indian | Pituitary screening | 8 weeks | 19.7 | 17 | Permanent | Very preterm, 45XO/46XY, Hypospadias | |||

| Female | 32 | 1420 | New Zealand European | Dysmorphism, macrocephaly, and seizures | 6 weeks | 10 | 15 | Permanent | Moderate preterm, RDS, later diagnosed with GDD | |||

| Screening detected | ||||||||||||

| Female | 24 + 3 | 650 | New Zealand European | Third | 5 weeks | 14 | 41 | 9.6 | Transient | 2 years | Extreme preterm, ELBW, CLD, Apnoea of prematurity, RoP, PDA | |

| Male | 27 + 5 | 1105 | Fijian | Second | Borderline second screen, third sample requested | 4 weeks | 74 | >100 | 3.7 | Transient | 2.5 years | Extreme preterm, VLBW, RDS, CLD, left inguinal hernia, CMV |

| Male | 28 + 6 | 900 | Cook Island Māori | Second | 3 weeks | 13 | 39.9 | 12.7 | Transient | 2.5 years | Very preterm, ELBW, RDS, hypospadias with chordee | |

| Female | 29 + 5 | 720 | Cook Island Māori | Second | 3 weeks | 78 | 138 | 6 | Permanent | Very preterm, ELBW, RDS, CLD, Twin 2 | ||

| Female | 30 + 1 | 1455 | Chinese | Second | 4 weeks | 22 | 49 | 9.9 | Transient | 5 years | Very preterm, VLBW, RDS, jaundice, maternal GDM | |

| Female | 30 + 5 | 1065 | New Zealand Māori | Second | 17 days | 32 | >100 | 3.2 | Transient | 3 years | Very preterm, VLBW, apnoea of prematurity, AOP, PDA | |

| Female | 32 + 1 | 1235 | Samoan | Second | 4 weeks | 19 | 42.2 | 10.9 | Transient | 6 months | Moderate preterm, VLBW, RDS, SGA | |

| State or Country | First Sample | Second Sample | Third Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aotearoa New Zealand [17] | 48–72 h | 14 days if BW < 1500 g | 28 days if BW < 1000 g |

| Queensland, Australia [2] | 48–72 h | 14 days if BW < 1500 g | 28 days if BW < 1000 g |

| Western Australia, Australia [2] | 48–72 h | 14 days if BW < 1500 g | 28 days if BW < 1000 g |

| South Australia, Australia [2] | At or near 48 h | 10 days if BW < 1500 g | 30 days or discharge if BW < 1500 g |

| Victoria, Australia [2,21] | 36–72 h | 4 weeks or discharge if BW < 1500 g or GA < 32 weeks | |

| New South Wales, Australia [2] | 48–72 h | 1 month if BW < 1500 g or GA < 30 weeks | |

| British Columbia, Canada [23] | 24–48 h | 21 days or day of discharge if BW < 1500 g | |

| United Kingdom [24] | 5 days | 28 days or day of discharge if GA < 32 weeks | |

| Wisconsin, USA [15] | 24–48 h | 14 days if BW < 2000 g or GA < 34 weeks | 30 days for all infants |

| Japan [25] | 5–7 days | 4 weeks or body weight reaches 2500 g or at discharge if BW < 2000 g |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Neonatal Screening. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brown, A.; Hofman, P.; Webster, D.; Heather, N. Screening Blind Spot: Missing Preterm Infants in the Detection of Congenital Hypothyroidism. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2025, 11, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11020037

Brown A, Hofman P, Webster D, Heather N. Screening Blind Spot: Missing Preterm Infants in the Detection of Congenital Hypothyroidism. International Journal of Neonatal Screening. 2025; 11(2):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11020037

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrown, Ashleigh, Paul Hofman, Dianne Webster, and Natasha Heather. 2025. "Screening Blind Spot: Missing Preterm Infants in the Detection of Congenital Hypothyroidism" International Journal of Neonatal Screening 11, no. 2: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11020037

APA StyleBrown, A., Hofman, P., Webster, D., & Heather, N. (2025). Screening Blind Spot: Missing Preterm Infants in the Detection of Congenital Hypothyroidism. International Journal of Neonatal Screening, 11(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11020037