Anxiety Sensitivity, Uncertainty and Recursive Thinking: A Continuum on Cyberchondria Conditions During the COVID Outbreak

Abstract

:Introduction

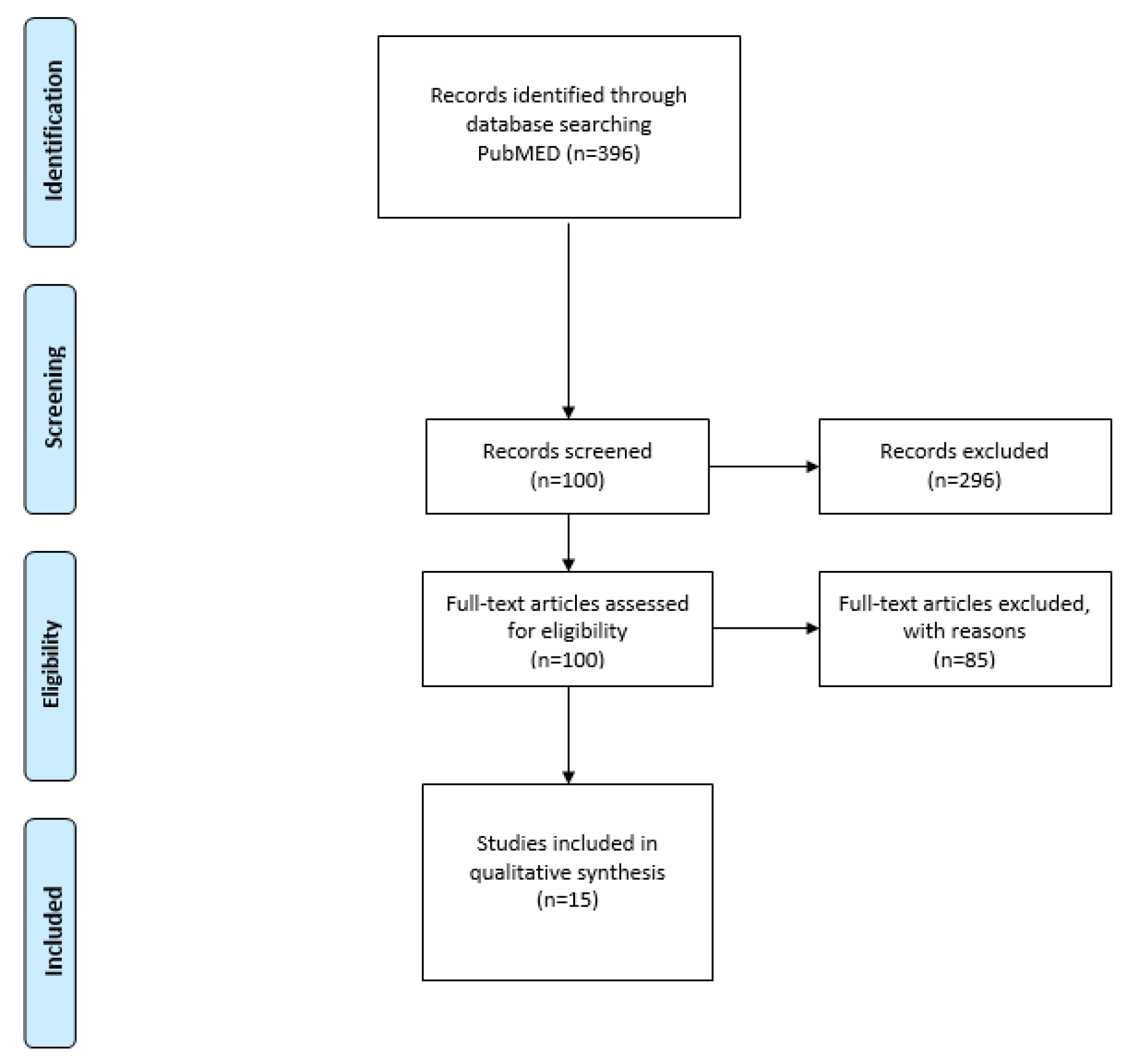

Methods

Research Strategy

| Number | Search term |

| 1 | Cyberchondria [all fields] |

| 2 | Anxiety [all fields] |

| 3 | Quarantine [all fields] |

| 4 | 1 OR 2 |

| 5 | AND 3 |

| 6 | English [Language] |

| 7 | 2015/01/01 to 2020/12/20 [publication date] |

The selection criteria for the study

Results

| REFERENCES (Author) | AIM | SAMPLE | TYPE OF MEASURE | FINDINGS |

| Bai et al. (2004) [23] | This study investigated stress reactions among staff members in the hospital, during the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). | 338 staff members in a hospital in East Taiwan. | -Anonymous SARS-related stress reactions questionnaire, comprising acute stress disorder criteria according to DSMIV criteria and related emotional and behavioral changes. -The personnel department sent the questionnaires. | The results highlighted the value of shortened work hours as a means by which the tremendous stress caused by a SARS outbreak can be reduced and the value of unambiguous information in reducing uncertainty. Quarantined staff members were at a high risk of developing an acute stress disorder. |

| Casagrande et al. (2020) [42] | This study investigated the effects of the quarantine period for Covid-19, in the Italian population. | 2,291 participants. | - The online survey collected information on the socio-demographic data and additional information concerning the Covid-19 pandemic. | The results revealed that the participants reported poor sleep, high anxiety, and high distress. |

| Cava et al. (2005) [22] | The aim of this study was to explore the experience of home quarantine during the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) | 21 participants. | -All interviews were audiotaped and followed a semi structured interview guideline. | The results showed that people felt uncertainty and anxiety after the quarantine period. |

| Desclaux et al. (2017) [24] | The aim of this study was to analyze the contact cases’ perceptions and acceptance of contact monitoring at the field level, during the Ebola virus. | 74 participants. | -Semi-Structured interview | The quarantine period for the Ebola epidemic was associated with mood disorders. |

| DiGiovanni et al. (2004) [31] | The aim of this study was to explore the factors influencing compliance with quarantine in Toronto during the 2003 SARS outbreak. | 35 participants were affected by the SARS epidemic. | -General Population Survey. | The results of this study showed increased levels of stress in people after the quarantine period. |

| Farooq et al. (2020) [20] | This study investigated the impact of online information on the individual-level intention to voluntarily self-isolate during the pandemic (COVID-19) | 11 participants. | - Multi-item scales were used to measure cyberchondria, information overload, threat and coping appraisal construct. All the constructs were measured using a 5-point scale. | The author showed the relationship between online information and self-isolation during the pandemic period (COVID-19). During COVID-19, the frequent use of social media contributed to information overload and over concern among individuals. |

| Hashemi et al. (2020) [2] | This study proposed a model in order to understand the associations between problematic internet use (PIU), cyberchondria, anxiety sensitivity, metacognition beliefs, and fear of COVID-19. | 651 participants. | Utilizing a cross-sectional online survey, 651 Iranians completed the following psychometric scales: Metacognition Questionnaire-30 (MCQ-30), Anxiety Sensitivity Questionnaire (ASI), Cyberchondria Severity Scale-Short Form (CSS-12), Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV–19S), and Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale (GPIUS). | The relationship between problematic use internet and cyberchondria with fear of COVID-19 was significantly mediated by anxiety sensitivity and metacognitive beliefs, because the fear of COVID-19 was found to be significantly associated with cyberchondria and anxiety sensitivity. |

| Jalloh et al. (2018) [43] | The authors studied the impact of the Ebola experiences and risk perceptions on Mental health. | 3,564 participants. | -Patient Health Questionnaire-4. -Events of Events Scale-revised. | During this period, people felt anxiety and depression. |

| Jokic-Begic et al. (2020) [16] | The aim of this study was to examine how cyberchondria is related to changes in levels of COVID-19. | 966 participants. | -Short Cyberchondria Scale (SCS) -Questionnaire regarding COVID-19 | The results demonstrated that the cyberchondria plays an important role in anxiety during the pandemic period. |

| Jungmann & Witthöft (2020) [19] | The aim of this study was to investigate the links between trait health anxiety, cyberchondria, and virus anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. | 1,615 participants | - The German short version of the Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS15). - The Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI) - The Short Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ short) - Questions specific to the COVID-19 pandemic. | The participants reported a significantly increasing virus anxiety in recent months (the previous months recorded retrospectively), especially among individuals with heightened trait health anxiety. Cyberchondria showed positive correlations with the current virus anxiety. |

| Lee et al. (2005) [17] | This research studied stigma among the residents of Amoy Gardens (AG), the first officially recognized site of community outbreak of SARS in Hong Kong. | 15 participants. | -A self–report questionnaire was constructed from a content analysis of the focus group. | The findings showed that stigma affected most residents and took various forms of being shunned, insulted, marginalized, and rejected by the people. |

| Lei et al. (2020) [44] | This research aimed at assessing and comparing the prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among the public affected by quarantine during Covid-19. | 1,593 participants. | -Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) | This study demonstrated there was a prevalence of anxiety and depression in people during the pandemic period. |

| Liu et al. (2020) [45] | This study identified factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic. | 898 young adults (18-30 years). | -questionnaire for assessing the levels of anxiety, depression and PTSD symptoms. | People reported high levels of depression, anxiety and PTSD symptoms, and high levels of loneliness. |

| Maftei & Holman (2020) [1] | This study investigated the effect of two opposing traits, optimism and neuroticism, on cyberchondria during the COVID-19 pandemic. | 880 participants. | - The Life Orientation Test (LOT) - the Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS) - The Neuroticism Scale from the international personality item pool—IPIP) | The results showed that neuroticism, age, and being female are positively associated with cyberchondria. |

| Mihashi et al. (2009) [18] | This study investigated strategies for broad mass isolation during the outbreaks of infectious diseases. | 300 participants. | -General Health Questionnaire. | This study suggested important strategies for the management of the psychological aspects of infectious diseases. |

| Wester et al. (2019) [26] | This study studied stigma during the exposure to the infection with Ebola among healthcare workers. | Swedish Healthcare workers who worked in Africa during 2014 (in Ebola period). | -General Health Questionnaire. | This study reported that the infectious diseases increased anxiety among people. |

Discussion

Conclusions

Conflict of interest disclosure

Compliance with ethical standards

References

- Maftei, A.; Holman, A.C. Cyberchondria During the Coronavirus Pandemic: The Effects of Neuroticism and Optimism. Front Psychol. 2020, 11, 567345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyed Hashemi, S.G.; Hosseinnezhad, S.; Dini, S.; Griffiths, M.D.; Lin, C.Y.; Pakpour, A.H. The mediating effect of the cyberchondria and anxiety sensitivity in the association between problematic internet use, metacognition beliefs, and fear of COVID-19 among Iranian online population. Heliyon. 2020, 6, e05135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anandkumar, S. Effect of pain neuroscience education and dry needling on chronic elbow pain as a result of cyberchondria: a case report. Physiother Theory Pract. 2015, 31, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichenberg, C.; Schott, M. Use of Web-Based Health Services in Individuals With and Without Symptoms of Hypochondria: Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2019, 21, e10980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huberty, J.; Dinkel, D.; Beets, M.W.; Coleman, J. Describing the use of the internet for health, physical activity, and nutrition information in pregnant women. Matern Child Health J. 2013, 17, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Bashir, M.; Khan, K.; Farooq, S.; Shoaib, S.; Farhan, S. Effect of presence and absence of parents on the emotional maturity and perceived loneliness in adolescents. J Mind Med Sci. 2021, 8, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, U.; Dell’Osso, B.; Fiorillo, A.; Mucic, D.; Aboujaoude, E. Internet-related psychopathology: clinical phenotypes and perspectives in an evolving field. J Psychopathol. 2015, 21, 406–414. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.W.; Horvitz, E. Cyberchondria: studies of the escalation of medical concerns in web search. ACM Transactions on Information Systems. 2009, 27, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, H.J. Possibilities and limitations of DSM-5 in improving the classification and diagnosis of mental disorders. Psychiatr Pol. 2018, 52, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, K.J.; Skritskaya, N.; Doherty, E.; Fallon, B.A. Advances in understanding illness anxiety. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008, 10, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, T.A. Anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty as potential risk factors for cyberchondria: A replication and extension examining dimensions of each construct. J Affect Disord. 2015, 184, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergus, T.A.; Spada, M.M. Cyberchondria: Examining relations with problematic Internet use and metacognitive beliefs. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2017, 24, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norr, A.M.; Oglesby, M.E.; Raines, A.M.; Macatee, R.J.; Allan, N.P.; Schmidt, N.B. Relationships between cyberchondria and obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 230, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starcevic, V.; Aboujaoude, E. Cyberchondria, cyberbullying, cybersuicide, cybersex: "new" psychopathologies for the 21st century? World Psychiatry. 2015, 14, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcevic, V.; Berle, D. Cyberchondria: towards a better understanding of excessive health-related Internet use. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013, 13, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokic-Begic, N.; Lauri Korajlija, A.; Mikac, U. Cyberchondria in the age of COVID-19. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0243704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Chan, L.Y.; Chau, A.M.; Kwok, K.P.; Kleinman, A. The experience of SARS-related stigma at Amoy Gardens. Soc Sci Med. 2005, 61, 2038–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihashi, M.; Otsubo, Y.; Yinjuan, X.; Nagatomi, K.; Hoshiko, M.; Ishitake, T. Predictive factors of psychological disorder development during recovery following SARS outbreak. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungmann, S.M.; Witthöft, M. Health anxiety, cyberchondria, and coping in the current COVID-19 pandemic: Which factors are related to coronavirus anxiety? J Anxiety Disord. 2020, 73, 102239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A.; Laato, S.; Islam, A.K.M.N. Impact of Online Information on Self-Isolation Intention During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovetta, A.; Bhagavathula, A.S. COVID-19-Related Web Search Behaviors and Infodemic Attitudes in Italy: Infodemiological Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, M.A.; Fay, K.E.; Beanlands, H.J.; McCay, E.A.; Wignall, R. The experience of quarantine for individuals affected by SARS in Toronto. Public Health Nurs. 2005, 22, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Lin, C.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Chen, J.Y.; Chue, C.M.; Chou, P. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv. 2004, 55, 1055–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desclaux, A.; Badji, D.; Ndione, A.G.; Sow, K. Accepted monitoring or endured quarantine? Ebola contacts' perceptions in Senegal. Soc Sci Med. 2017, 178, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawryluck, L.; Gold, W.L.; Robinson, S.; Pogorski, S.; Galea, S.; Styra, R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004, 10, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wester, M.; Giesecke, J. Ebola and healthcare worker stigma. Scand J Public Health. 2019, 47, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bati, A.H.; Mandiracioglu, A.; Govsa, F.; Çam, O. Health anxiety and cyberchondria among Ege University health science students. Nurse Educ Today. 2018, 71, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, T.A.; Spada, M.M. Moving toward a metacognitive conceptualization of cyberchondria: Examining the contribution of metacognitive beliefs, beliefs about rituals, and stop signals. J Anxiety Disord. 2018, 60, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.; Schlebusch, L.; Gaede, B. Support for family members who are caregivers to relatives with acquired brain injury. J Mind Med Sci. 2021, 8, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrer, P.; Cooper, S.; Tyrer, H.; Wang, D.; Bassett, P. Increase in the prevalence of health anxiety in medical clinics: Possible cyberchondria. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2019, 65, 566–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiovanni, C.; Conley, J.; Chiu, D.; Zaborski, J. Factors influencing compliance with quarantine in Toronto during the 2003 SARS outbreak. Biosecur Bioterror. 2004, 2, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.R.; Agho, K.E.; Stevens, G.J.; Raphael, B. Factors influencing psychological distress during a disease epidemic: data from Australia's first outbreak of equine influenza. BMC Public Health. 2008, 8, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibler, R.C.; Jastrowski Mano, K.E.; O'Bryan, E.M.; Beadel, J.R.; McLeish, A.C. The role of pain catastrophizing in cyberchondria among emerging adults. Psychol Health Med. 2019, 24, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sima, R.M.; Olaru, O.G.; Cazaceanu, A.; Scheau, C.; Dimitriu, M.T.; Popescu, M.; Ples, L. Stress and anxiety among physicians and nurses in Romania during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Mind Med Sci. 2021, 8, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, E.; Shevlin, M. The development and initial validation of the cyberchondria severity scale (CSS). J Anxiety Disord. 2014, 28, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T. Seeking health information on the internet: lifestyle choice or bad attack of cyberchondria? Media, Culture & Society. 2006, 28, 521–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathes, B.M.; Norr, A.M.; Allan, N.P.; Albanese, B.J.; Schmidt, N.B. Cyberchondria: Overlap with health anxiety and unique relations with impairment, quality of life, and service utilization. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 261, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajcar, B.; Babiak, J. Self-esteem and cyberchondria: The mediation effects of health anxiety and obsessive– compulsive symptoms in a community sample. Current Psychology. 2019, 40, 2820–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, J.; Fischerauer, S.F.; Talaei-Khoei, M.; Chen, N.C.; Oh, L.S.; Vranceanu, A.M. What are the Implications of Excessive Internet Searches for Medical Information by Orthopaedic Patients? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019, 477, 2665–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.F.A. Pandemic Fatigue. Ir Med J. 2020, 113, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casagrande, M.; Favieri, F.; Tambelli, R.; Forte, G. The enemy who sealed the world: effects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population. Sleep Med. 2020, 75, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalloh, M.F.; Li, W.; Bunnell, R.E.; Ethier, K.A.; O'Leary, A.; Hageman, K.M.; Sengeh, P.; Jalloh, M.B.; Morgan, O.; Hersey, S.; Marston, B.J.; Dafae, F.; Redd, J.T. Impact of Ebola experiences and risk perceptions on mental health in Sierra Leone, July 2015. BMJ Glob Health. 2018, 3, e000471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Xu, M. Comparison of Prevalence and Associated Factors of Anxiety and Depression Among People Affected by versus People Unaffected by Quarantine During the COVID-19 Epidemic in Southwestern China. Med Sci Monit. 2020, 26, e924609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Zhang, E.; Wong, G.T.F.; Hyun, S.; Hahm, H.C. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leykin, Y.; Muñoz, R.F.; Contreras, O. Are consumers of Internet health information "cyberchondriacs"? Characteristics of 24,965 users of a depression screening site. Depress Anxiety. 2012, 29, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty-Torstrick, E.R.; Walton, K.E.; Fallon, B.A. Cyberchondria: Parsing Health Anxiety From Online Behavior. Psychosomatics. 2016, 57, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, E.; Kearney, M.; Touhey, J.; Evans, J.; Cooke, Y.; Shevlin, M. The CSS-12: Development and Validation of a Short-Form Version of the Cyberchondria Severity Scale. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2019, 22, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, N.; Abbas, A. Use of Internet for health issues: Potential for Cyberchondria. Medical Science. 2014, 14, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pozza, A.; Ferretti, F.; Coluccia, A. The Perception of Physical Health Status in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2019, 15, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermingham, S.L.; Cohen, A.; Hague, J.; Parsonage, M. The cost of somatisation among the working-age population in England for the year 2008-2009. Ment Health Fam Med. 2010, 7, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Asmundson, G.J.; Fergus, T.A. The Concept of Health Anxiety. In The Clinician's Guide to Treating Health Anxiety; Academic Press, 2019; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartright, M.A.; White, R.W.; Horvitz, E. Intentions and attention in exploratory health search. In Proceedings of the 34th international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in Information Retrieval. 2011; pp. 65–74. [CrossRef]

- Durmayüksel, E.; Çinar, F.; Guven, B.B.; Aslan, F.E. Risk factors for the development of delirium in elderly patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Invest Surg. 2021, 6, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Risco, A.; Mejia, C.R.; Delgado-Zegarra, J.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; Arce-Esquivel, A.A.; Valladares-Garrido, M.J.; Rosas Del Portal, M.; Villegas, L.F.; Curioso, W.H.; Sekar, M.C.; Yáñez, J.A. The Peru Approach against the COVID-19 Infodemic: Insights and Strategies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020, 103, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Gao, C.; Tang, C.; Wang, H.; Tao, Z. Prevalence of hypochondriac symptoms among health science students in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0222663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, K.L. Cyberchondria in relation to uncertainty and risk perception. Bachelor's thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, the Netherlands. 2016. https://essay.utwente.nl/69904/1/Schulte_BA_PSY.

- Karabeliova, S.; Ivanova, E. Do Personality Traits Lead to Cyberchondria and What are the Outcomes for Well-being? The European Health Psychologist. 2014, 16, 782. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, M.; Kirwan, G. Prognoses for diagnoses: medical search online and “cyberchondria”. BMC Proceedings. 2012, 6, P30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, E.; Karabeliova, S. Elaborating on Internet addiction and cyberchondria–relationships, direct and mediated effects. Journal of Education Culture and Society. 2014, 5, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullan, R.D.; Berle, D.; Arnáez, S.; Starcevic, V. The relationships between health anxiety, online health information seeking, and cyberchondria: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019, 245, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajcar, B.; Babiak, J.; Olchowska-Kotala, A. Cyberchondria and its measurement. The Polish adaptation and psychometric properties of the Cyberchondria Severity Scale CSS-PL. Psychiatr Pol. 2019, 53, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, H.M.; Salkovskis, P.M. Hypochondriasis. Behav Res Ther. 1990, 28, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.; Gregory, J.D.; Walker, I.; Lambe, S.; Salkovskis, P.M. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Health Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2017, 45, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salkovskis, P.M.; Warwick, H. Making sense of hypochondriasis: A cognitive theory of health anxiety. In Health anxiety: Clinical and research perspectives on hypochondriasis and related conditions; Wiley, 2001; pp. 46–64. ISBN 978-0-471-49104-0. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, H.K.; Brach, C.; Harris, L.M.; Parchman, M.L. A proposed 'health literate care model' would constitute a systems approach to improving patients' engagement in care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013, 32, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suziedelyte, A. How does searching for health information on the Internet affect individuals' demand for health care services? Soc Sci Med. 2012, 75, 1828–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zangoulechi, Z.; Yousefi, Z.; Keshavarz, N. The Role of Anxiety Sensitivity, Intolerance of Uncertainty, and Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms in the prediction of Cyberchondria. Advances in Bioscience and Clinical Medicine. 2018, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2022 by the author. 2022 Carmela Mento, Maria Catena Silvestri, Pilar Amezaga, Maria R. Anna Muscatello, Valentina Romeo, Antonio Bruno1, Clemente Cedro1

Share and Cite

Mento, C.; Silvestri, M.C.; Amezaga, P.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Romeo, V.; Bruno, A.; Cedro, C. Anxiety Sensitivity, Uncertainty and Recursive Thinking: A Continuum on Cyberchondria Conditions During the COVID Outbreak. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2022, 9, 78-87. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.91.P7887

Mento C, Silvestri MC, Amezaga P, Muscatello MRA, Romeo V, Bruno A, Cedro C. Anxiety Sensitivity, Uncertainty and Recursive Thinking: A Continuum on Cyberchondria Conditions During the COVID Outbreak. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2022; 9(1):78-87. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.91.P7887

Chicago/Turabian StyleMento, Carmela, Maria Catena Silvestri, Pilar Amezaga, Maria R. Anna Muscatello, Valentina Romeo, Antonio Bruno, and Clemente Cedro. 2022. "Anxiety Sensitivity, Uncertainty and Recursive Thinking: A Continuum on Cyberchondria Conditions During the COVID Outbreak" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 9, no. 1: 78-87. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.91.P7887

APA StyleMento, C., Silvestri, M. C., Amezaga, P., Muscatello, M. R. A., Romeo, V., Bruno, A., & Cedro, C. (2022). Anxiety Sensitivity, Uncertainty and Recursive Thinking: A Continuum on Cyberchondria Conditions During the COVID Outbreak. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 9(1), 78-87. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.91.P7887