Abstract

Background. Contemporary literature indicates that there is significant support and assistance provided by schools for young autistic people, which has had a positive impact on the accessibility of jobs. Nevertheless, the employment rate of autistic people is unacceptably low in the UK. The current study investigated teachers’ views on the preparation for employment of young autistic people in the UK. Methods. Interviews were conducted with individuals from the educational field and thematic analysis was used to explore the teachers’ views regarding the factors that have an impact on the preparation for employment of young autistic people. Results. Four main themes emerged from the analysis. These themes included awareness, funding and government support, action plans and motivation. Conclusion. These results have critical implications for the educational field and future research, which are discussed in the paper.

Introduction

Employment is crucial for health and well-being, as it enhances one’s self esteem and self-confidence [1,2,3,4,5]. Previous literature indicates that employment allows individuals to form new relationships and to experience a sense of value and personal achievement [6]. Not only does it provide one with income to support their needs and desires, but it also offers a sense of belonging, increasing happiness and self-satisfaction [7]. Indeed, there is evidence that employment bolsters psychological welfare in individuals with mental health concerns [8], promoting the individuals’ levels of pride and self-esteem. It goes without saying that employment is critical for psychological welfare.

Autism is characterized by difficulties in communication and social interaction and by engagement in repetitive thoughts and behaviors [9,10]. A report published by the Office for National Statistics indicated that the UK employment rate was recorded at 75.1%, on April 20th, 2021 [11]. However, the search published by the National Autistic Society stated that only 22% of autistic adults are engaged in any kind of paid employment, despite 77% of autistic adults expressing the desire to be employed [12]. These results highlight the worryingly low employment rates among autistic people.

Previous research by Lorenz investigated the barriers for autistic individuals entering the job market. The authors reported that the decreased employment rates amongst autistic people could be due to barriers during the job application process; namely, the perception that autistic individuals will be less able to swiftly adapt to new work environments and possess communication skills that differ from those of non-autistic people [13]. Hence, the researchers attempted to find ways in order to overcome these barriers. For example, the authors reported that clear, explicit and direct communication was helpful when liaising with autistic employees and reduced miscommunication at the work place.

Furthermore, numerous studies have investigated the way in which young students are prepared by schools for employment in the UK [14,15]. The researchers interviewed nine teaching staff members and examined the actions that schools are taking to prepare young autistic adults for employment. The findings indicated that schools are offering tailored packages and educational practices are being adapted in an individualistic manner for autistic students. Nesbit reported that schools often fail to prepare autistic individuals for employment [16]. Moreover, the researchers identified a gap in the literature regarding the instructions that are given to young autistic adults for school-related employment skills, with most of the research being based on young autistic children [17]. Overall, it is clear that young autistic people are not receiving adequate support from educational institutions regarding employment opportunities.

Previous research has focused largely on secondary school pupils or educational schemes. Indeed, despite notable research investigating the knowledge and experiences of teachers in the UK [18], most studies utilize questionnaire-based methods. The current study aimed to investigate teachers’ views on the preparation for employment of young autistic people in the UK via online interviews due to the Covid-19 pandemic. This research focused on schools with special educational needs, as they often have smaller sized classes which allow teachers to develop a more detailed understanding of their students’ abilities and needs [19,20]. Additionally, semi-structured interviews were used to gain a deeper, more holistic understanding of their perceptions.

Materials and Methods

Design

This research utilized a qualitative approach. Using a qualitative approach allowed the researchers to ascertain a deeper understanding of the participants’ experiences [21]. In addition, the qualitative approach allowed participants to provide insights that are specific to the research questions and researchers were able to make more accurate conclusions based on the participants’ views and perspectives [22].

Participants

The participants were teachers who work in UK schools for special educational needs and teachers who have had years of experience in working with young autistic people. Each of the participants had taught in either primary or secondary schools, which helped this study gain a broader range of voices, experiences and opinions on their views on the preparation for employment of young autistic people in the UK. The participants were sampled through social media pages, including LinkedIn, Facebook and Instagram.

There was a sample of four participants, all of whom worked in the educational field in the UK. Out of the total sample (N=4), there were two male participants and two female participants. The participants’ age ranged from 35 to 64 years and each participant had more than six years of experience in teaching autistic students.

All participants were informed of the purposes of the research and were provided with an information sheet, to give participants clear and accurate information about what their participation would entail. Additionally, all the participants gave their informed consent, prior to completing the online interview.

Measures

A bespoke semi-structured interview schedule was devised to investigate teachers’ views on the preparation for employment of young autistic people in the UK. The interviews involved a mixture of open and closed questions. There were open questions, such as, “If you were able to change one aspect of the system to improve the preparation towards employment of these children, what would it be? Why?” There were also closed questions, such as, “Do you think the support provided by schools is sufficient?” There were five demographic questions asked at the beginning which inquired about the participant’s age, gender, the type of school they are currently teaching at, the number of years of experience and the number of different schools they had worked at. The participants were asked questions regarding their opinion on how schools prepare young autistic people for employment. The participants discussed the beneficial aspects of the schooling system to support autistic students in finding employment and explained their views on the systemic improvements that could be made.

Procedure

The ethical approval for this research was gained from the Department of Psychology and Human Development at the UCL Institute of Education. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the interviews took place online via Microsoft Teams. At the beginning of the interview, the participants were reminded about the purpose of the study and were informed of the procedure. The interview schedule was arranged beforehand, which consisted of five demographic questions and six questions which were more specific to the teachers’ view on the preparation of young autistic people in the UK. However, the interviews were semi-structured, meaning that the participants had the freedom to elaborate on their opinions and researchers had the chance to explore questions in more depth. Finally, the interviews lasted for approximately 20-30 minutes.

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the transcriptions of the interviews in order to identify patterns, trends and meanings through forming codes and themes. This research used the Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke approach which entails a six-step process [23]. Firstly, the transcript was read multiple times to observe trends and meanings and notes were taken. Secondly, codes were formed from the meanings and trends that were reported from the interview transcripts. Following this step, the codes which were associated with each other were grouped together and then combined into broader themes. Once these themes were set, they were reviewed to examine whether the themes had enough data to be substantive. Finally, once the themes were formulated, the findings were explored and interpreted. It is crucial that when using the thematic analysis approach, the themes should not be made from the research question, but should be identified from the data. Also, themes should have enough data to support them in order to be convincing [23].

Results

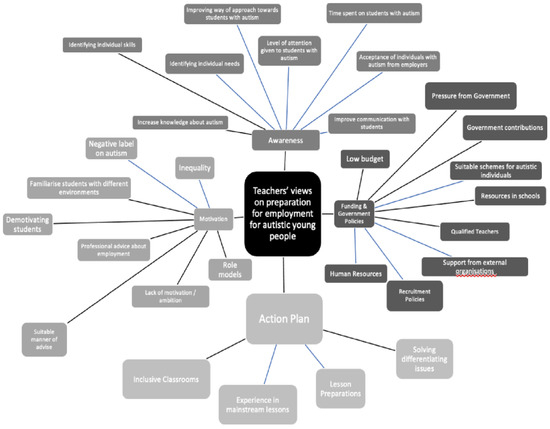

The interviews were analyzed using the thematic analysis and numerous codes were formed on the transcripts. Using the codes that were formed, four main themes emerged. The four main themes were:

- Awareness

- Funding and Government Support

- Action Plans

- Motivation

Figure 1.

Diagram of themes and subthemes from the data collected.

1. Awareness

This first theme was formed based on codes, such as: the teachers’ need to improve their knowledge about autism, to identify individual skills and needs, the level of attention given to autistic students and many more. The data showed that when teachers spoke about awareness, they implied that the school staff, school students and employers should improve their knowledge of autism in order to improve their understanding of how to support autistic students. In addition, participants stated that teachers should be more aware of the individual strengths and needs of autistic students by helping them prepare for employment in an effective manner.

For example, when a participant was asked whether anything has changed in the way schools prepare young autistic people for employment, they responded by saying that “Every year could be different because we personalize it to the students ... I think every year we’ve always tried to keep it more personal to each student.” The participant’s answer indicated that schools attempt to adjust their methods of preparations according to the individuals’ strengths and needs, which makes the preparation for employment more specific, effective and personal.

Another participant discussed the importance of employers increasing their knowledge and acceptance of autistic individuals. For instance, a participant stated the following: “I think a lot of employers are very unsure as to how to provide the appropriate support, particularly for people with more complex needs. So, I think perhaps improving the way that we transition people into employment with an understanding of the individual needs, supporting the educators for the individuals, as well as supporting the employers are all really, really important.”

The statement of the participant emphasized the importance of increasing awareness of autism in workplaces and the necessity of employers to provide more opportunities for young autistic adults to find employment. Additionally, this suggested that teachers believe that employers are also responsible for the employment gap for autistic people.

The data also showed that some teachers are aware that autistic students need additional support and attention. For example, one participant mentioned, “In the past, if they needed a visit to a college, sometimes we sent one of our staff members with them. So, from our school’s perspective, I think we do quite a lot. And if any parent requests it or for anything extra, we normally try our best to support them as much as we can.” This suggests that teachers endeavor to proactively support autistic students and help them experience novel environments. This plays an important role in teachers and schools preparing young autistic adults for employment.

2. Funding and Government Support

The theme ‘Funding and Government Support’ was extracted from the data as all participants mentioned that the lack of government funding and the low budgets provided to schools was a key reason why schools are not appropriately preparing young autistic adults for employment.

Participant 1 stated that it is important to recruit SEN qualified teachers as they have increased knowledge and experience in supporting autistic students. Also, by recruiting more SEN qualified teachers, there would be additional benefits as teachers who are not SEN qualified can get advice on working with autistic students. However, participant 1 mentioned that the limited budgets prevent schools from recruiting as many SEN qualified teachers as would be desirable.

Participant 4 was asked why he/she thinks that the employment rate for autistic individuals is so low. The participant’s response was, “I think that despite the limited resources, they do their best, but there is only so much they can do on the budget.” In addition, when participant 4 was asked about whether anything has changed in the way schools prepare autistic people for their future and employment, the participant stated with a tone of disappointment that schools have not got the time to prepare autistic students for employment and discussed that they believe that it is due to budget restraints. Participants have highlighted that they believe that budget restraints and the lack of funding are issues and drawbacks in preparing young autistic adults for employment.

However, the data collected indicated that there had been government contributions which had a positive impact on helping schools prepare young autistic adults for employment.

For instance, participant 2 was asked about the most beneficial aspect of the schooling system to help autistic students find employment and the participant answered, “The National Career Service provides a range of options and I think things like that are becoming increasingly aware of the challenges faced by people with neurodiverse backgrounds. NIMH as well, you’re aware of them. I mean, you have got a lot of charities working in the sector as well, so I think it’s really important that the government sector returned to the benefits of the charity sector on schooling.”

3. Action Plans

The ‘Action Plans’ theme was extracted from the data, as participants reported that making action plans has a positive impact on preparing young autistic adults for employment. Participant 1 stated that action plans must be made to solve differentiating issues between autistic children and non-autistic children.

Participant 2 was asked about what works well when schools train autistic people for employment. The participant replied by saying, “So, the first thing is to understand the individual needs and then you work through a plan of action with them regarding the typical traits associated with a diagnosis of autism.” Participant 2 implied that it is important to make an action plan specific to individuals based on their abilities, in order to make it more effective in preparing them for employment. Participant 3 also stated “I think every year we’ve always tried to keep it more personal to each student for those students who are autistic anyway.”

This demonstrates that schools are performing action plans which are tailored to individual needs in order to enhance and improve the preparation of young autistic adults for employment.

Participant 3 noted that autistic students are prepared for employment by experiencing the transition from specialized schools to mainstream education. For instance, “I think what benefits them is that they have their specialist provisions, but they are also integrated into the mainstream, which resume appears because when, when they, if they leave a specialized school and go straight out, they kind of find that difficult.” This suggested that schools enable autistic students to experience the setting transitions when moving from specialized schools to mainstream schools, which is helpful in preparing for employment.

4. Motivation

The final theme that emerged was ‘Motivation’ and this entails an important role in preparing young autistic adults for employment. The data suggested that schools affect the students’ level of motivation both positively and negatively. For example, participant 3 stated, “I’m actually going out on a field trip next week where I’m taking some year 10 students to a sixth form college where they can experience what the day is like at a college. We do quite a lot to prepare them for that next step.” Participant 3 said that students are given the opportunity to experience college environments which may motivate them to find employment in a similar atmosphere, if they enjoy this environment. This implies that some teachers perceive that autistic students lack motivation as a consequence of their experiences and that this can serve as a barrier to accessing employment.

Participant 3 was asked about which aspect he/she would change in the schooling system in order to improve preparation for employment. The participant said that they believe that schools should find more work experience projects that can improve accessibility for autistic students, as this may positively motivate students as it gives them a clearer idea of the nature of employment. In addition, participant 3 stated, “… to get them in contact with students like themselves that have now left school and college or have found employment, to come and talk to them… It’s alright for us to say oh yeah, you can do this and this could happen, but I think they benefit more from speaking to somebody their own age who has been through what they’re going through currently. I think they would really benefit from it.” This is strongly related to the theme ‘motivation’, as students having the opportunity to interact with others who are employed allows them to ask questions, gain advice and be told about their experiences. This was assumed to positively motivate autistic students and bolster their confidence.

However, there can be negative effects on students’ motivation. Participant 2 stated, “… if you have any condition, regardless of the nature of the condition, and you’re constantly saying that this condition will hold you back, there comes a point where you start to believe it. I think it’s really important that the kind of role models that we have in our education system represent diversity of every kind, so there’s always somebody that a child could look up to and take after and be sure that if they have succeeded, they can also do that.” Once again, the participant emphasizes the positive impact of having role models for young autistic adults. It also demonstrates the perceived detrimental effects of negative stigma on the motivation of autistic students.

Similarly, when participant 4 was asked about young adults’ level of ambition for employment, he/she answered, “Some do. Some, if you talk to some, they’re just like, you know, if you ask them what they want to do with their lives, they simply say stay at home and watch TV.” This statement showed that the teachers believe that some autistic young people are not motivated to seek employment; however, it was unclear whether this perception was domain-general across all school-age children. Participant 4 elaborated that their school has career advisors who come from external organizations and talk to autistic students about their future in order to provide advice. Despite this seeming as though it would have a positive impact on students’ motivation, the participant stated that it had the opposite effect. Participant 4 highlighted, “… they’re very blunt. So, they will just turn and say that erm, you can’t do that, which you know, with, with an autistic child, it’s not preparing them. You need to, you know, say that, think about options you could have, but they just go, no, you’re not suitable for that.” This indicates that the staff can perpetuate stigmas associated with a diagnosis of autism, which can serve to reduce the students’ motivation in pursuing careers in particular professions.

Participant 3 also voiced beliefs that autistic students are less ambitious than mainstream students and that this is likely due to the stigma associated with the diagnosis. This participant was asked whether they are aware if some autistic individuals have access to employment preparation outside schools. He/she explained, “…when we do offer the work experience, it’s offered to all the students regardless, but we do find a lot of autistic students who won’t take it up or don’t want to do it, but the offer is always there.” This suggests that some teachers perceive autistic students to be less motivated to pursue work experience opportunities. Whilst exploring the nature of this would be a fruitful avenue for future research, it suggests that schools need to find new and creative ways of supporting autistic students in accessing these opportunities.

Discussion

This study aimed at investigating the teachers’ views on the preparation for employment of young autistic people in the UK. The findings suggested that both primary and secondary school teachers believed that there needs to be greater awareness of autism, schools need to be provided with increased funding and government support, schools need to prepare effective action plans according to autistic students’ goals and teachers need to focus on improving the students’ levels of motivation.

Awareness was mentioned by all participants. In particular, teachers’ awareness of a student’s strengths and needs was highlighted as a critical point, so that students can be supported and prepared for employment in an individualistic manner. Previous research underscored the importance of teachers acknowledging their student’s strengths and needs, as it allows them to form a meaningful bond and give teachers deeper knowledge about their student’s strengths [24]. This would give teachers a clearer insight on how to prepare their students for employment. The participants also mentioned the importance of raising awareness amongst employers. This is because it is important that autistic people are given equal opportunities to be employed and find jobs in the UK. Previous research looked at the perspectives of employers who have worked with autistic individuals at the workplace [25]. The findings indicated that employers reported positive experiences of working with autistic people and mentioned that there was an increased level of recognition of the contributions made by young autistic adults within the organisation. Previous research supports the finding that increasing awareness amongst employers and encouraging inclusive hiring strategies leads to positive organizational outcomes.

Participants reported that there is an urgent need to increase the amount of funding and resources that schools receive. An increase in funding and resources would allow schools to hire more SEN qualified teachers who may be better placed to support autistic students [26]. This would aid the preparation of young autistic adults for employment, by improving access to resources such as SEN professionals who could provide autistic children with advice for employment. Whilst the government has increased the awareness and support for autistic people, participants felt that there is more to be done to help schools prepare autistic students for employment.

The findings of this study indicated that some teachers believe that action plans play a key role in preparation for employment. Teachers prepare action plans and make adjustments according to the individuals, depending on their skills, strengths and abilities. Furthermore, action plans help teachers record progress and make reflections [27,28,29]. This suggests that action plans enable teachers to monitor students and better prepare them for employment.

Motivation was a factor discussed by the participants and, in their views, schools provide autistic students with opportunities to boost their level of motivation. However, the participants also noted that there are factors which can deter autistic students from employment. Schools work with external organizations to provide students with career advice. However, some members in these organizations may have insufficient knowledge of how to best support autistic individuals and it was indicated that this can have a maladaptive influence on the students’ confidence. Nevertheless, schools do field trips with these young adults to colleges to give them an experience of a different environment, which was implied to encourage students to find employment and work in a similar setting.

Limitations

Nevertheless, this study had numerous limitations. One primary limitation of this study was that a small sample was collected. This was a limitation as the codes and the themes were developed from the data collected which were based on the views of four participants. However, if there had been more participants with a wider range of experience from different types of schools (primary or secondary) in the UK, the results could have been more readily generalizable. Nevertheless, these results provide a springboard for future research to more extensively examine the teachers’ views on the preparation for employment of young autistic people.

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to investigate teachers’ views on the preparation for employment of young autistic people in the UK. After using Microsoft Teams to interview a sample of four participants who work in the educational field, the findings revealed that there were four areas that the teachers thought impacted the effectiveness of the preparation for employment of young autistic people in UK. The four themes were awareness, funding and government support, action plans and motivation. These findings will aid future research, as researchers can use the themes to examine the impact that these themes have on preparation for employment. Schools can focus their efforts on these four themes and examine whether improving these areas has a positive impact on the preparation for employment of young autistic people in the UK.

Conflict of interest disclosure

There are no known conflicts of interest in the publication of this article. The manuscript was read and approved by all authors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies and that such approvals are acknowledged within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Liam Myles would like to thank the Harding Distinguished Postgraduate Scholars Programme Leverage Scheme and the Economic and Social Research Council Doctoral Training Partnership for funding his research at the University of Cambridge.

References

- Chrétien, S.L.; Ensink, K.; Descoteaux, J.; Normandin, L. Measuring grandiose and vulnerable narcissism in adolescents. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrozzino, D.; Costabile, A.; Patierno, C.; Settineri, S.; Fulcheri, M. Clinical psychology in school and educational settings: emerging trends. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, R.E.; Wallach, M.A. Employment is a critical mental health intervention. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modini, M.; Joyce, S.; Mykletun, A.; Christensen, H.; Bryant, R.A.; Mitchell, P.B.; Harvey, S.B. The mental health benefits of employment: Results of a systematic metareview. Australasian Psychiatry; 2016, 24, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamir B Self-esteem and the psychological impact of unemployment. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1986, 49, 61–72. [CrossRef]

- Davenport, L.J.; Allisey, A.F.; Page, K.M.; LaMontagne, A.D.; Reavley, N.J. How can organizations help employees thrive? The development of guidelines for promoting positive mental health at work. International Journal of Workplace Health Management. 2016, 9, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, R.; Eggleton, I.R.C. The effect of different types of employment on quality of life. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005, 49, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, E.W.; Aknin, L.B.; Norton, M.I. Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science. 2008, 319, 1687–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, K.; Gazestani, V.H.; Bacon, E.; et al. Evaluation of the diagnostic stability of the early autism spectrum disorder phenotype in the general population starting at 12 months. JAMA pediatrics. 2019, 173, 578587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, H.V. Theoretical aspects of autism: Causes— A review. Journal of Immunotoxicology. 2011, 8, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Autistic Society (NAS). 2021. Available online: https://www.autism.org.uk/what-we-do/news/newdata-on-the-autism-employment-gap.

- Office for National Statistics. Employment and Labour Market. 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/.

- Lorenz, T.; Frischling, C.; Cuadros, R.; Heinitz, K. Autism and Overcoming Job Barriers: Comparing Job-Related Barriers and Possible Solutions in and outside of AutismSpecific Employment. PloS ONE 2016, 11, e0147040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, A.; Rafferty, A. Making it to work: Towards employment for the young adult with autism. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2001, 36, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, E.M.; McNabney, S.M.; Frisone, F.; et al. Compassion and suppression in caregivers: twin masks of tragedy and joy of caring. J Mind Med Sci. 2020, 7, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilopoulou, E.; Nisbet, J. The quality of life of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2016, 23, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, P.F.; Lainer, I. Addressing the Needs of Adolescents and Adults with Autism: A Crisis on the Horizon. J Contemp Psychother. 2011, 41, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, J.; Retell, J. Teaching Careers: Exploring Links Between Well-Being, Burnout, Self-Efficacy and Praxis Shock. Front Psychol. 2020, 10, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algraigray, H.; Boyle, C. The SEN label and its effect on special education. Educational and Child Psychology. 2017, 34, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sakka, S.; Nikopoulou, V.A.; Bonti, E.; Tatsiopoulou, P.; Karamouzi, P.; Giazkoulidou, A.; Tsipropoulou, V.; Parlapani, E.; Holeva, V.; Diakogiannis, I. Assessing test anxiety and resilience among Greek adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic. J Mind Med Sci. 2020, 7, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banister, P.; Bunn, G.; Burman, E.; Daniels, J.; Duckett, P.; Goodley, D.; Lawthorn, R.; Parker, I.; Runswick-Cole, K.; Sixsmith, J.; Smailes, S.; Tindall, C.; Whelan, P. Qualitative Methods in Psychology: A Research Guide, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: Berkshire (OU) & New York (McGHE), 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, E.; Coyle, A. Introduction to qualitative psychological research. Analysing qualitative data in psychology. 2007, 2, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Russell, A. Understanding the role of selfdetermination in shaping university experiences for autistic and typically developing students in the United Kingdom. Autism. 2021, 25, 1262–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, D.; Mitchell, W.; Zulla, R.; Dudley, C. Perspectives of employers about hiring individuals with autism spectrum disorder: Evaluating a cohort of employers engaged in a job-readiness initiative. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2019, 50, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, R.; Larrazabal, S.; Berwart, R. Educational policies and professional identities: the case of Chilean special educational needs (SEN) teachers under new regulations for SEN student inclusion in mainstream schools. Ethnography and Education. 2020, 15, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.L.; Hebl, M.R. Affirmative reaction: The influence of type of justification on nonbeneficiary attitudes toward affirmative action plans in higher education. Journal of Social Issues. 2005, 61, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, D.; Fraticelli, F.; Polcini, F.; Fulcheri, M.; Mohn, A.A.; Vitacolonna, E. A school educational intervention based on a serious game to promote a healthy lifestyle. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomai, M.; Langher, V.; Martino, G.; Esposito, F.; Ricci, M.E.; Caputo, A. Promoting the development of children with disabilities through school inclusion: clinical psychology in supporting teachers in Mozambique. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2021 by the author. 2021 Biranavan Thavapalan, Emanuele Maria Merlo