Quality of Life in Romanian Patients with Schizophrenia Based on Gender, Type of Schizophrenia, Therapeutic Approach, and Family History

Highlights

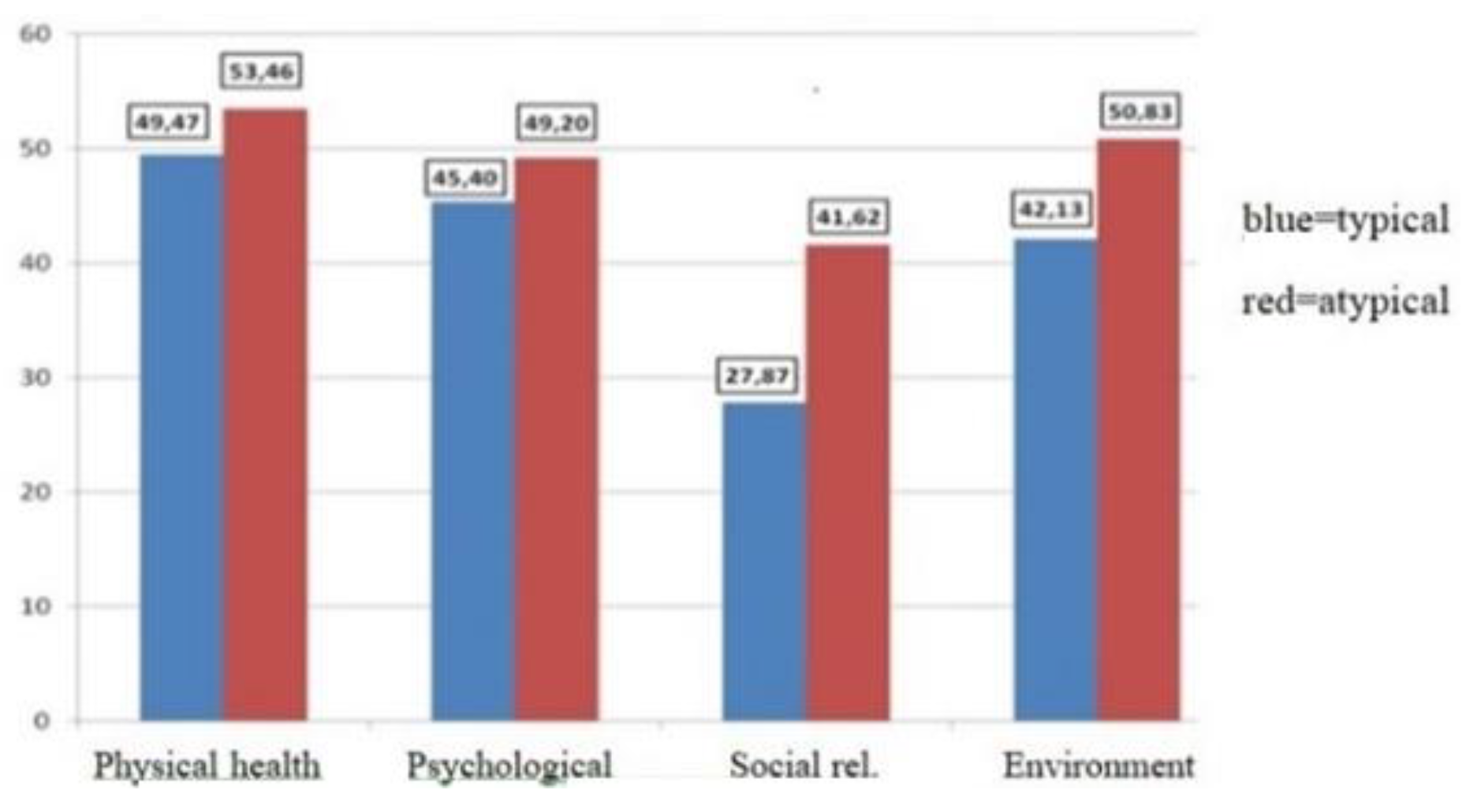

- The level of social integration, self-control and physical function is better in subjects who are treated with atypical neuroleptics.

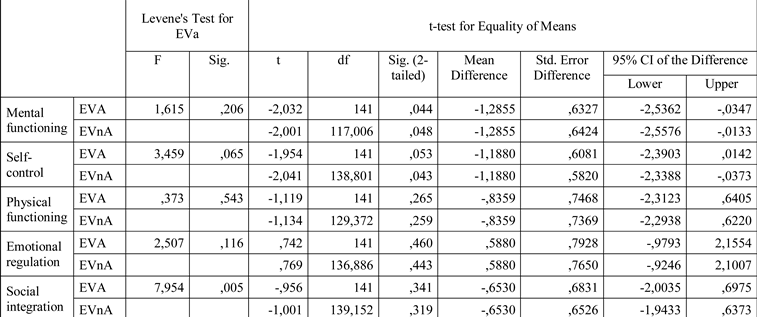

- Self-control, physical function and the capacity of emotional control is equally affected in both women and men with, while mental functioning would be better preserved in men.

Abstract

Highlights

- ✓ The level of social integration, self-control and physical function is better in subjects who are treated with atypical neuroleptics.

- ✓ Self-control, physical function and the capacity of emotional control is equally affected in both women and men with, while mental functioning would be better preserved in men.

Introduction

Materials and Methods

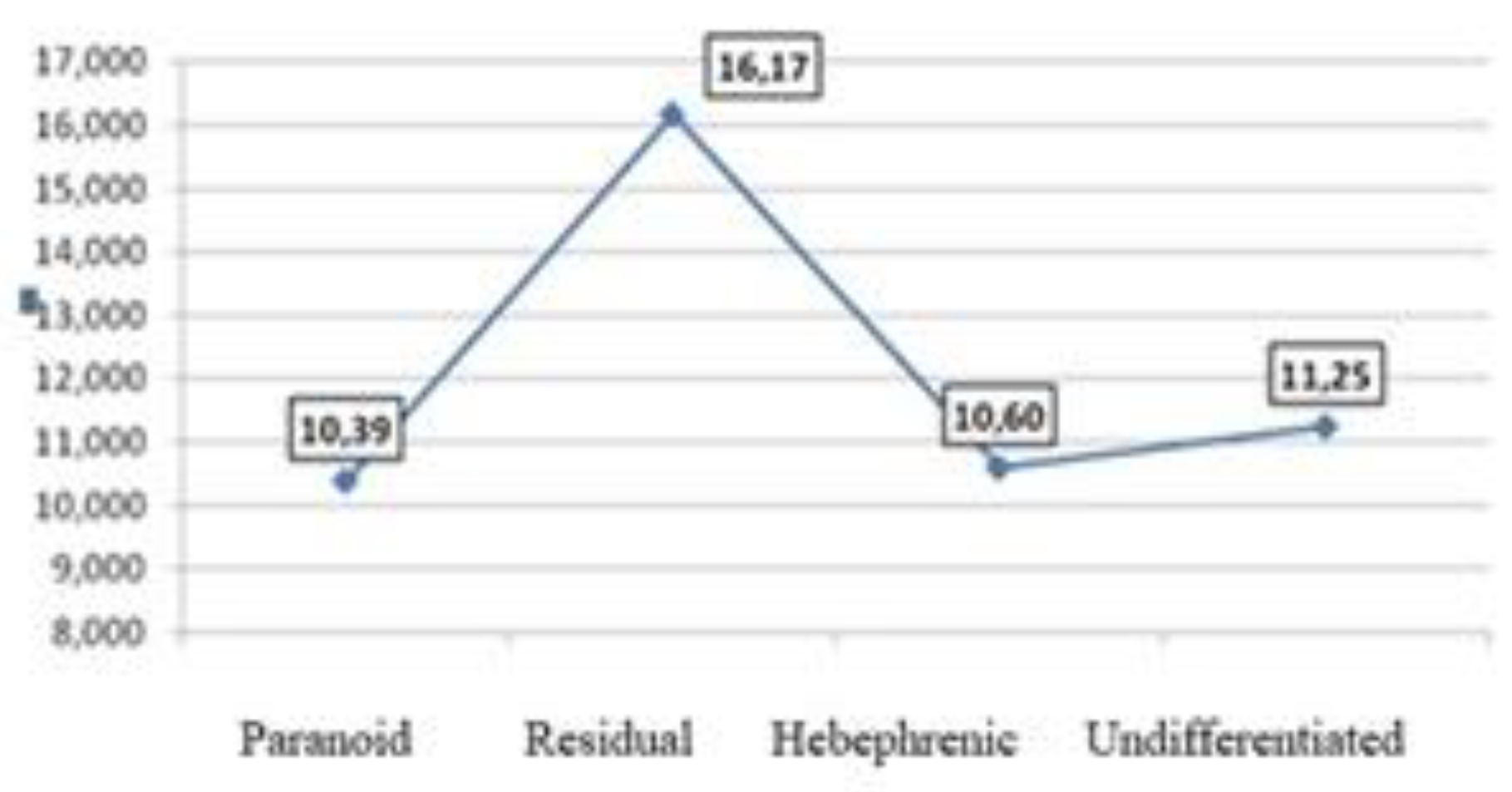

- Subjective Well-being under Neuroleptic Treatment Scale (SWN) [12,13,14], a self-assessment scale with the initial form of 38 items and a short variant of 20 items (10 negative and 10 positive scored items), each being scored on a Likert 6-step scale. The purpose of the scale is to show the subjective experience of the patient during neuroleptic treatment, having 5 distinct topics: physical functioning, mental functioning, self- control, emotional regulation, and social integration. A high value indicates better functioning of the patient on the respective domain. The scale has an overall evaluation of both the efficiency and the quality of the medical treatment in schizophrenia, but it also includes the subjective well-being of the respondents, and further offers the possibility of evaluating the subjective perception of the patient, no matter the psychopathology [15,16].

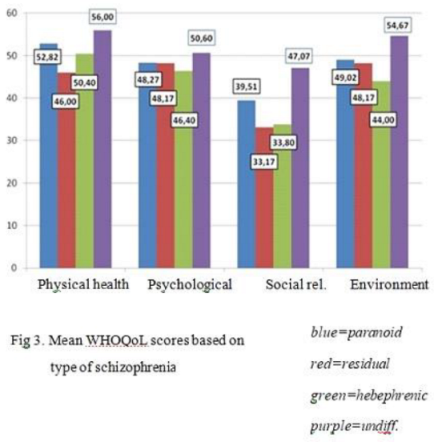

- World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHO- QoL – BREF) [17,18,19]; in our analysis, we used scores related to 4 domains of quality of life (physical, psychological, social, and living environment), while 2 other items were evaluated separately. The patients’ answers were quantified using a 5-step Likert scale. High values correspond to a high level of satisfaction regarding quality of life [20,21,22].

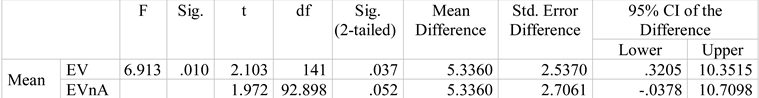

Results

Discussions

Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowling, A. What things are important in people's lives? A survey of the public's judgements to inform scales of health related quality of life. Soc Sci Med. 1995, 41, 1447–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symanski, S.; Lieberman, J.A.; Alvir, J.M.; et, at. Gender Differences in onset of ilness, treatment response, course in first episode schizophrenic patients. Amer J Pshychiatry. 1995, 152, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, D.J.; Abel, K.; Takei, N.; Murray, R.M. Gender differences in schizophrenia: Hormonal effect or subtypes? Schziophrenia Bulletin. 1995, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Test, M.A.; Burke, S.S.; Wallisch, L.S. Gender differences of young adults with schizophrenic disorders in community care. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1990, 16, 331–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, J.; Jody, D.; Geisler, S.; et al. Time course and biologic correlates of treatment response in first episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993, 50, 369–76 PMID: 8098203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opjordsmoen, S. Long-term clinical outcome of schizophrenia with special reference to gender differences. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991, 83, 307–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardenstein, K.K.; McGlashan, T.H. Gender differences in affective, schizoaffective and schizo- phrenic disorders: A review. Schizoph Res. 1990, 3, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ring, N.; Tatitam, D.; Motitague, L.; et al. Gender differences in the incidence of definite schizophrenia and atypical psychosis – Focus on negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Acta Psychi Scand. 1991, 84, 489–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadock, B.; Sadock, V.; Ruiz, P. Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry; 2017; ISBN 9781451100471. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), 4th ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0890420256.

- World Health Organization. The International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1993.

- Naber, D.; Moritz, S.; Lambert, F.; Rajonk, R.; Holzbach, R.; Mass, B.; et al. Improvement of schizophrenic patients’ subjective well-being under atypical antipsychotic drugs. Schizophr Res. 2001, 50, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schennach-Wolff, R.; Jäger, M.; Obermeier, M.; Schmauss, M.; Laux, G.; Pfeiffer, H.; et al. Quality of life and subjective well-being in schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders: Valid predictors of symptomatic response and remission? World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010, 11, 729–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naber, D. A self-rating to measure subjective effects of neuroleptic drugs, relationships to objective psychopathology, quality of life, compliance and other clinical variables. Int Clin Psycholpharmacol. 1995, 10 (Suppl. S3), 133–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karow, A.; Czekalla, J.; Dittmann, R.W.; Schacht, A.; Wagner, T.; Lambert, M.; et al. Association of subjective well-being, symptoms, and side effects with compliance after 12 months of treatment in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007, 68, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naber, D.; Karow, A.; Lambert, M. Subjective well- being under neuroleptic treatment and its relevance for compliance. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005, 111, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skevington, S.M.; Sartorius, N.; Amir, M. Developing methods for assessing quality of life in different cultural settings. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOLBREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998, 28, 551–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skevington, S.M.; Lotfy, M.; O'Connell, K.A.; WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. Qual Life Res. 2004, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Carroll, R.E.; Smith, K.; Couston, M.; Cossar, J.A.; Hayes, P.C. A comparison of the WHOQOL-100 and the WHOQOL-BREF in detecting change in quality of life following liver transplantation. Qual Life Res. 2000, 9, 121–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Division of mental health and prevention of substance abuse. In WHOQOL-User Manual; World Health Organization, 1998.

- Fang, C.T.; Hsiung, P.C.; Yu, C.F.; Chen, M.Y.; Wang, J.D. Validation of the World Health Organization quality of life instrument in patients with HIV infection. Qual Life Res. 2002, 11, 753–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallant, J.F. SPSS Survival Manual: a step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS, 4th ed.; Allen&Unwin: Crows Nest, NSW, USA, 2011; ISBN 9781742373928. [Google Scholar]

- Druică, E.; Druică, I.; Ianole, R.; Sandu, M. Statistica pe înţelesul tuturor; Editura C.H. Beck, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, A.F. A Quality of Life Interview for the chronically mentally ill. Eval. Program Plan. 1988, 11, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skantze, K.; Malm, U.; Dencker, S.J.; May, P.R.; Corrigan, P. Comparison of quality of life with standard of living in schizophrenic out-patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1992, 161, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, S.; Roe, M.; Lane, A.; Gervin, M.; Morris, M.; Kinsella, A.; Larkin, C.; Callaghan, E.O. Quality of life in schizophrenia: relationship to sociodemographic factors, symptomatology and tardive dyskinesia. Acta Psychiatrica Scand. 1996, 94, 118–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, H.Y.; Burnett, S.; Bastani, B.; Ramirez, L.F. Effects of six months of clozapine treatment on the quality of life of chronic schizophrenic patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1990, 41, 892–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeman, M.V. Interaction of sex, age, and neuroleptic dose. Compr Psychiatry. 1983, 24, 125–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, G.L.; Glick, I.D.; Clarkin, J.F.; Spencer, J.H.; Lewis, A.B. Gender and schizophrenia outcome: a clinical trial of an inpatient family intervention. Schizophr Bull. 1990, 16, 277–92 PMID: 2197716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shtasel, D.L.; Gur, R.E.; Gallacher, F.; Heimberg, C.; Gur, R.C. Gender differences in the clinical expression of schizophrenia. Schizoph Res. 1992, 7, 225–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paunica, M.; Manole, A.; Motofei, C.; Tanase, G.L. The Globalization in the actual Context of the European Union Economy. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2018, 12, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.T.; Weng, Y.Z.; Leung, C.M.; Tang, W.K.; Chan, S.S.; Wang, C.Y.; Han, B.; Ungvari, G.S. Gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristic and the quality of life of Chinese schizophrenia patients. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010, 44, 450–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, J.M.; Ciudad, A.; Gascón, J.; Gómez, J.C.; EFESO Study Group. Safety, effectiveness, and quality of life of olanzapine in first-episode schizophrenia: A naturalistic study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003, 27, 667–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, C.W.; Chiu, E.; Harrigan, S.; Hall, K.; Hassett, A.; Macfarlane, S.; Mastwyk, M.; O'Connor, D.W.; Opie, J.; Ames, D. The impact upon extra-pyramidal side effects, clinical symptoms and quality of life of a switch from conventional to atypical antipsychotics (risperidone or olanzapine) in elderly patients with schizophrenia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003, 18, 432–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voruganti, L.; Cortese, L.; Owyeumi, L.; Kotteda, V.; Cernovsky, Z.; Zirul, S.; Awad, A. Switching from conventional to novel antipsychotic drugs: Results of a prospective naturalistic study. Schizoph Res. 2002, 57, 201–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crossley, N.A.; Constante, M.; McGuire, P.; Power, P. Efficacy of atypical v. typical antipsychotics in the treatment of early psychosis: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010, 196, 434–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilian, R.; Angermeyer, M.C. The effects of antipsychotic treatment on quality of life of schizophrenic patients under naturalistic treatment conditions: An application of random effect regression models and propensity scores in an observational prospective trial. Qual Life Res. 2005, 14, 1275–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, M.; Naber, D. Current issues in schizophrenia: overview of patient acceptability, functioning capacity and quality of life. CNS Drugs. 2004, 18, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, R.M.; Malla, A.K.; McLean, T.; Voruganti, L.P.; Cortese, L.; McIntosh, E.; Cheng, S.; Rickwood, A. The relationship of symptoms and level of functioning in schizophrenia to general wellbeing and the Quality of Life Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000, 102, 303–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motofei, I.G.; Rowland, D.L.; Georgescu, S.R.; Tampa, M.; Baconi, D.; Stefanescu, E.; Baleanu, B.C.; Balalau, C.; Constantin, V.; Paunica, S. Finasteride adverse effects in subjects with androgenic alopecia: A possible therapeutic approach according to the lateralization process of the brain. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016, 27, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueoka, Y.; Tomotake, M.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneda, Y.; Taniguchi, K.; Nakataki, M.; Numata, S.; Tayoshi, S.; Yamauchi, K.; Sumitani, S.; Ohmori, T.; Ueno, S.; Ohmori, T. Quality of life and cognitive dysfunction in people with schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011, 35, 53–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, B.F.; Resende, C.B.; Carvalhaes, C.F.; Cardoso, C.S.; Teixeira, A.L.; Keefe, R.S.; Rocha, F.L.; Salgado, J.V. Interview-based assessment of cognition is a strong predictor of quality of life in patients with schizophrenia and severe negative symptoms. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2016, 38, 216–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sigaudo, M.; Crivelli, B.; Castagna, F.; Giugiario, M.; Mingrone, C.; Montemagni, C.; Rocca, G.; Rocca, P. Quality of life in stable schizophrenia: The relative contributions of disorganization and cognitive dysfunction. Schizophr Res. 2014, 153, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2008 by the author. 2008 Elena Alina Roșca, Ovidiu Alexinschi, Călin Brîncuș, Valentin Petre Matei, Ana Giurgiuca

Share and Cite

Roșca, E.A.; Alexinschi, O.; Brîncuș, C.; Matei, V.P.; Giurgiuca, A. Quality of Life in Romanian Patients with Schizophrenia Based on Gender, Type of Schizophrenia, Therapeutic Approach, and Family History. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2018, 5, 202-209. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.52.P202209

Roșca EA, Alexinschi O, Brîncuș C, Matei VP, Giurgiuca A. Quality of Life in Romanian Patients with Schizophrenia Based on Gender, Type of Schizophrenia, Therapeutic Approach, and Family History. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2018; 5(2):202-209. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.52.P202209

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoșca, Elena Alina, Ovidiu Alexinschi, Călin Brîncuș, Valentin Petre Matei, and Ana Giurgiuca. 2018. "Quality of Life in Romanian Patients with Schizophrenia Based on Gender, Type of Schizophrenia, Therapeutic Approach, and Family History" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 5, no. 2: 202-209. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.52.P202209

APA StyleRoșca, E. A., Alexinschi, O., Brîncuș, C., Matei, V. P., & Giurgiuca, A. (2018). Quality of Life in Romanian Patients with Schizophrenia Based on Gender, Type of Schizophrenia, Therapeutic Approach, and Family History. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 5(2), 202-209. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.52.P202209