Health Status After Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

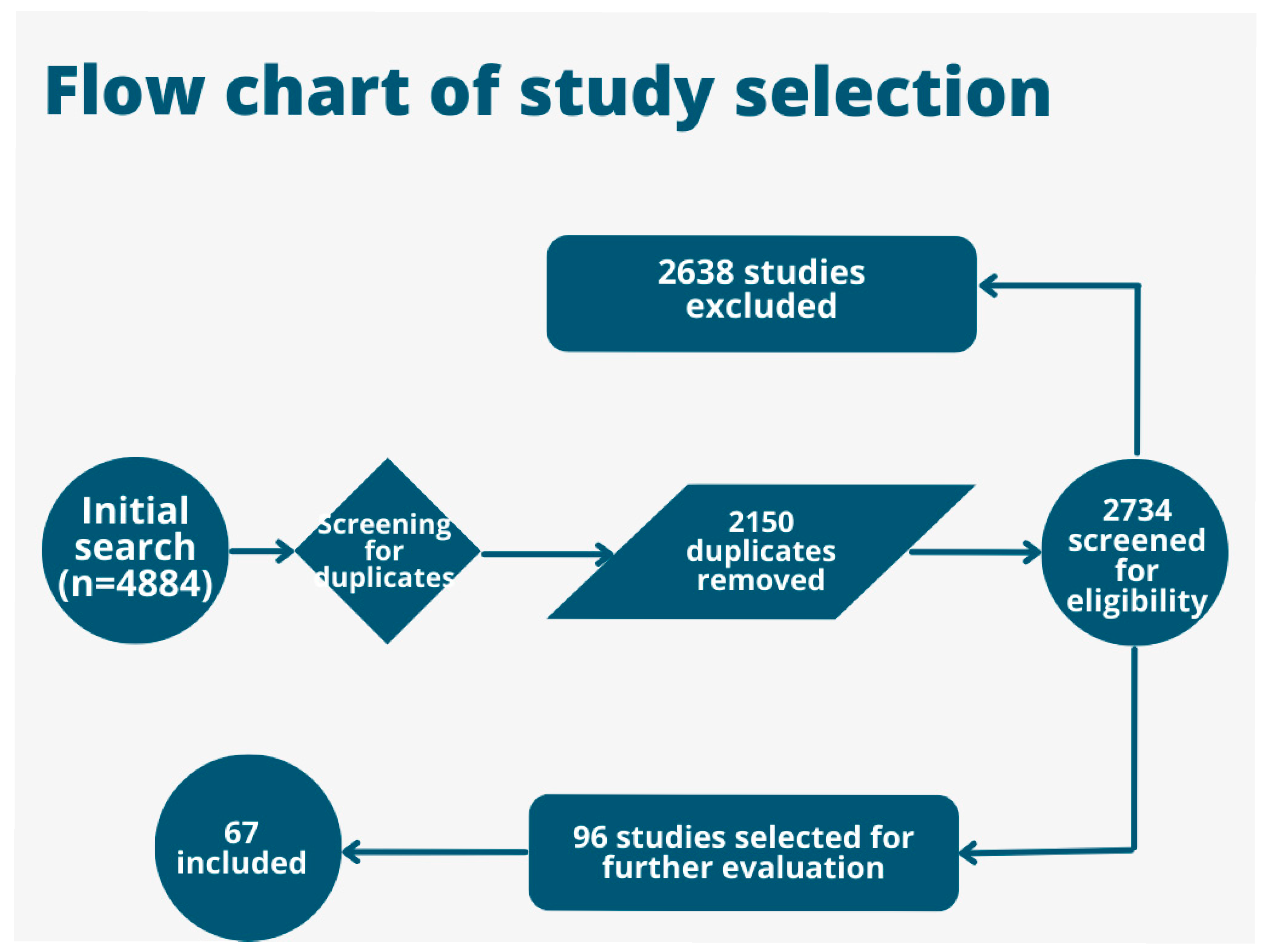

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Study design: quantitative or qualitative original research.

- Language: published in English.

- Availability: full text accessible.

- Population: adult patients (≥18 years) preparing for or having undergone total hip arthroplasty (THA).

- Outcomes: reporting on health-related quality of life (QoL) before and/or after THA.

- Age group: studies restricted to pediatric populations.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

- Duplicate reports or overlapping datasets.

- Abstracts, conference proceedings, or protocols without full text.

- Reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, commentaries.

- Anatomical focus: interventions targeting joints other than the hip (e.g., knee, shoulder).

- Patient population: non-arthroplasty indications (e.g., cerebral palsy).

- Outcomes: studies evaluating postoperative endpoints unrelated to QoL (e.g., fracture healing, infection rates, prosthesis mechanics).

2.4. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Etiology of Coxarthrosis

4. Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA)

5. QoL Assessment

6. Results

6.1. Preoperative Quality of Life in Coxarthrosis Patients

6.2. Postoperative QoL in Coxarthrosis Patients

6.3. Comparisons of QoL Between Preoperative and Postoperative Phases

6.4. Factors Influencing QoL in Coxarthrosis Patients

7. Discussion and Implications for Clinical Practice

8. Limitations and Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Palo, N.; Chandel, S.S.; Dash, S.K.; Arora, G.; Kumar, M.; Biswal, M.R. Effects of Osteoarthritis on Quality of Life in Elderly Population of Bhubaneswar, India. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2015, 6, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novelli, A.; Frank-Tewaag, J.; Franke, S.; Weigl, M.; Sundmacher, L. Exploring Heterogeneity in Coxarthrosis Medication Use Patterns before Total Hip Replacement: A State Sequence Analysis. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e080348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdoğan, F.; Can, A. The Effect of Previous Pelvic or Proximal Femoral Osteotomy on the Outcomes of Total Hip Arthroplasty in Patients with Dysplastic Coxarthrosis. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 2020, 54, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kort, N.P.; Bemelmans, Y.F.L.; van der Kuy, P.H.M.; Jansen, J.; Schotanus, M.G.M. Patient Selection Criteria for Outpatient Joint Arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2017, 25, 2668–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manole, F.; Marian, P.; Mekeres, G.M.; Voiţă-Mekereş, F. Systematic Review of the Effect of Aging on Health Costs. Arch. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 14, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncay Duruöz, M.; Öz, N.; Gürsoy, D.E.; Hande Gezer, H. Clinical Aspects and Outcomes in Osteoarthritis. Best. Pr. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2023, 37, 101855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, H.; Wei, W.; Cheng, B. Multivariate Analysis of the Relationship between Gluteal Muscle Contracture and Coxa Valga. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, J.; Klatt, B. Essentials in Total Hip Arthroplasty; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-1-00-352401-4. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Q.; Wu, X.; Tao, C.; Gong, W.; Chen, M.; Qu, M.; Zhong, Y.; He, T.; Chen, S.; Xiao, G. Osteoarthritis: Pathogenic Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, Z.; Alexander, P.G.; Ocasio-Nieves, B.D.; Yocum, L.; Lin, H.; Tuan, R.S. Pathogenesis of Osteoarthritis: Risk Factors, Regulatory Pathways in Chondrocytes, and Experimental Models. Biology 2020, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelmer, G.; Stone, A.H.; Turcotte, J.; King, P.J. Reasons for Revision: Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty Mechanisms of Failure. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2021, 29, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, N.M.; Varnum, C.; Nelissen, R.G.H.H.; Overgaard, S.; Pedersen, A.B. The Association between Socioeconomic Status and the 30- and 90-Day Risk of Infection after Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Registry-Based Cohort Study of 103,901 Patients with Osteoarthritis. Bone Jt. J. 2022, 104-B, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Ling, L.; Qi, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Z.; Wang, W.; Tu, C.; Li, Z. Patients’ Risk Factors for Periprosthetic Joint Infection in Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Meta-Analysis of 40 Studies. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.T.; Moore, A.C.; Burris, D.L.; Price, C. Detrimental Effects of Long Sedentary Bouts on the Biomechanical Response of Cartilage to Sliding. Connect. Tissue Res. 2020, 61, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliorini, F.; Vecchio, G.; Pintore, A.; Oliva, F.; Maffulli, N. The Influence of Athletes’ Age in the Onset of Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2022, 30, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirò, S.; Foreman, S.C.; Joseph, G.B.; Souza, R.B.; McCulloch, C.E.; Nevitt, M.C.; Link, T.M. Impact of Different Physical Activity Types on Knee Joint Structural Degeneration Assessed with 3-T MRI in Overweight and Obese Subjects: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Skelet. Radiol. 2021, 50, 1427–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, X.; Kourkoumelis, N.; Shang, X. The Mysteries of Rapidly Destructive Arthrosis of the Hip Joint: A Systemic Literature Review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9, 1220–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaque, B.A. Short Stem for Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA)—Overview, Patient Selection and Perspectives by Using the Metha® Hip Stem System. Orthop. Res. Rev. 2022, 14, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanchini, F.; Piscopo, A.; Nasto, L.A.; Piscopo, D.; Boemio, A.; Cacciapuoti, S.; Iodice, G.; Cipolloni, V.; Fusini, F. Which Problematics in tha after Acetabular Fractures: Experience of 38 Cases. Orthop. Rev. 2022, 14, 38611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontea, M.; Bimbo-Szuhai, E.; Macovei, I.C.; Maghiar, P.B.; Sandor, M.; Botea, M.; Romanescu, D.; Beiusanu, C.; Cacuci, A.; Sachelarie, L.; et al. Anterior Approach to Hip Arthroplasty with Early Mobilization Key for Reduced Hospital Length of Stay. Medicina 2023, 59, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Awwad, A.; Tudoran, C.; Patrascu, J.M.; Faur, C.; Tudoran, M.; Mekeres, G.M.; Abu-Awwad, S.-A.; Csep, A.N. Unexpected Repercussions of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Total Hip Arthroplasty with Cemented Hip Prosthesis versus Cementless Implants. Materials 2023, 16, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatod, M.; Inacio, M.C.S.; Bini, S.A.; Paxton, E.W. Prophylaxis against Pulmonary Embolism in Patients Undergoing Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2011, 93, 1767–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, D.; Jain, V.K.; Iyengar, K.P.; Vaishya, R.; Malhotra, R. Total Hip Arthroplasty in Tubercular Arthritis of the Hip—Surgical Challenges and Choice of Implants. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma. 2021, 17, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derriennic, J.; Nabbe, P.; Barais, M.; Le Goff, D.; Pourtau, T.; Penpennic, B.; Le Reste, J.-Y. A Systematic Literature Review of Patient Self-Assessment Instruments Concerning Quality of Primary Care in Multiprofessional Clinics. Fam. Pr. 2022, 39, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabowska, I.; Antczak, R.; Zwierzchowski, J.; Panek, T. How to Measure Multidimensional Quality of Life of Persons with Disabilities in Public Policies—A Case of Poland. Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Gill, A.; Hussain, H.K. Evaluating the Potential of Artificial Intelligence in Orthopedic Surgery for Value-Based Healthcare. Int. J. Multidiscip. Sci. Arts 2023, 2, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrillo-Cárdenas, J.; Jiménez-Pérez, J.-R.; Feito, F.R. The Role of Virtual and Augmented Reality in Orthopedic Trauma Surgery: From Diagnosis to Rehabilitation. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 191, 105407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josipović, P.; Moharič, M.; Salamon, D. Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Slovenian Version of Harris Hip Score. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białkowska, M.; Stołtny, T.; Pasek, J.; Mielnik, M.; Szyluk, K.; Baczyński, K.; Hawranek, R.; Koczy-Baron, A.; Kasperczyk, S.; Cieślar, G.; et al. The Influence of Hip Arthroplasty on Health Related Quality of Life in Male Population with Osteoarthritis Hip Disease. Wiad. Lek. 2020, 73, 2627–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulzan, M.; Cavalu, S.; Abdelhamid, A.; Hozan, C.; Voiţă-Mekeres, F. Coxarthrosis Etiology Influences the Patients’ Quality of Life in the Preoperative and Postoperative Phase of Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2023, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalund, P.K.; Glassou, E.N.; Hansen, T.B. The Impact of Age and Preoperative Health-Related Quality of Life on Patient-Reported Improvements after Total Hip Arthroplasty. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 1951–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnowska, J.; Lewko, J.; Chilińska, J.; Cybulski, M.; Pogroszewska, W.; Krajewska-Kułak, E.; Sierżantowicz, R. The Impact of Early Rehabilitation and the Acceptance of the Disease on the Quality of Life of Patients after Hip Arthroplasty: An Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariconda, M.; Galasso, O.; Costa, G.G.; Recano, P.; Cerbasi, S. Quality of Life and Functionality after Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Long-Term Follow-up Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2011, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifan, D.F.; Tirla, A.G.; Moldovan, A.F.; Moș, C.; Bodog, F.; Maghiar, T.T.; Manole, F.; Ghitea, T.C. Can Vitamin D Levels Alter the Effectiveness of Short-Term Facelift Interventions? Healthcare 2023, 11, 1490. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37239776/ (accessed on 16 October 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoară, N.D.; Marian, P.; Petriș, A.O.; Delcea, C.; Manole, F. A Review of the Role of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy on Anxiety Disorders of Children and Adolescents. Pharmacophore 2023, 14, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Berkel, A.C.; Schiphof, D.; Waarsing, J.H.; Runhaar, J.; van Ochten, J.M.; Bindels, P.J.E.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A. 10-Year Natural Course of Early Hip Osteoarthritis in Middle-Aged Persons with Hip Pain: A CHECK Study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, J.; Blom, M.; Tuominen, U.; Seitsalo, S.; Lehto, M.; Paavolainen, P.; Hietaniemi, K.; Rissanen, P.; Sintonen, H. Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients Waiting for Major Joint Replacement. A Comparison between Patients and Population Controls. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2006, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, J.; Tuominen, U.; Seitsalo, S.; Lehto, M.; Paavolainen, P.; Hietaniemi, K.; Rissanen, P.; Sintonen, H.; Blom, M. The Effect of Waiting Time on Health-Related Quality of Life, Pain, and Physical Function in Patients Awaiting Primary Total Hip Replacement: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Value Health 2009, 12, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo Loures, E.; Leite, I.C. Analysis on Quality of Life of Patients with Osteoarthrosis Undergoing Total Hip Arthroplasty. Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2012, 47, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunescu, F.; Didilescu, A.; Antonescu, D.M. Does Physiotherapy Contribute to the Improvement of Functional Results and of Quality of Life after Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty? Maedica 2014, 9, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lavernia, C.J.; Villa, J.M.; Contreras, J.S. Alcohol Use in Elective Total Hip Arthroplasty: Risk or Benefit? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2013, 471, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCalden, R.W.; Charron, K.D.; MacDonald, S.J.; Bourne, R.B.; Naudie, D.D. Does Morbid Obesity Affect the Outcome of Total Hip Replacement?: An Analysis of 3290 THRs. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2011, 93, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, M.; Greene, M.; Frumento, P.; Rolfson, O.; Garellick, G.; Stark, A. Age- and Health-Related Quality of Life after Total Hip Replacement: Decreasing Gains in Patients above 70 Years of Age. Acta Orthop. 2014, 85, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perneger, T.V.; Hannouche, D.; Miozzari, H.H.; Lübbeke, A. Symptoms of Osteoarthritis Influence Mental and Physical Health Differently before and after Joint Replacement Surgery: A Prospective Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzer, M.; Pedneault, C.; Yakobov, E.; Hart, A.; Sullivan, M. Marital Relationship and Quality of Life in Couples Following Hip Replacement Surgery. Life 2021, 11, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telang, S.; Hoveidaei, A.H.; Mayfield, C.K.; Lieberman, J.R.; Mont, M.A.; Heckmann, N.D. Are Activity Restrictions Necessary After Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review. Arthroplast. Today 2024, 30, 101576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnis, S.E.; Wartemberg, G.K.; Khan, W.S.; Agarwal, S. A Literature Review of Total Hip Arthroplasty in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis: Perioperative Considerations and Outcome. Open Orthop. J. 2015, 9, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaballa, E.; Dennison, E.; Walker-Bone, K. Function and Employment after Total Hip Replacement in Older Adults: A Narrative Review. Maturitas 2023, 167, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiss, F.; Götz, J.S.; Maderbacher, G.; Meyer, M.; Reinhard, J.; Zeman, F.; Grifka, J.; Greimel, F. Excellent Functional Outcome and Quality of Life after Primary Cementless Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA) Using an Enhanced Recovery Setup. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lix, L.M.; Ayilara, O.; Sawatzky, R.; Bohm, E.R. The Effect of Multimorbidity on Changes in Health-Related Quality of Life Following Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. Bone Jt. J. 2018, 100, 1168–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Makimoto, K.; Higo, T.; Shigematsu, M.; Hotokebuchi, T. Changes in the WOMAC, EuroQol and Japanese Lifestyle Measurements among Patients Undergoing Total Hip Arthroplasty. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2009, 17, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Allison, K.; Hinman, R.S.; Bennell, K.L.; Spiers, L.; Knox, G.; Plinsinga, M.; Klyne, D.M.; McManus, F.; Lamb, K.E.; et al. Effects of Adding Aerobic Physical Activity to Strengthening Exercise on Hip Osteoarthritis Symptoms: Protocol for the PHOENIX Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, A.; Sandiford, M.H.; Menigaux, C.; Bauer, T.; Klouche, S.; Hardy, P. Pain Catastrophizing and Pre-Operative Psychological State Are Predictive of Chronic Pain after Joint Arthroplasty of the Hip, Knee or Shoulder: Results of a Prospective, Comparative Study at One Year Follow-Up. Int. Orthop. 2022, 46, 2461–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, S.N.; Nakonezny, P.A.; Richard, H.M.; Wells, J.E. Pain Catastrophizing, Anxiety, and Depression in Hip Pathology. Bone Jt. J. 2019, 101, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawker, G.A.; French, M.R.; Waugh, E.J.; Gignac, M.A.; Cheung, C.; Murray, B.J. The Multidimensionality of Sleep Quality and Its Relationship to Fatigue in Older Adults with Painful Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2010, 18, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppold, D.A.; Kandil, F.I.; Güttler, O.; Müller, A.; Steckhan, N.; Meiß, S.; Breinlinger, C.; Nelle, E.; Hartmann, A.M.; Jeitler, M.; et al. Effects of Prolonged Fasting during Inpatient Multimodal Treatment on Pain and Functional Parameters in Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis: A Prospective Exploratory Observational Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampazo-Lacativa, M.K.; Santos, A.A.; Coimbra, A.M.; D’Elboux, M.J. WOMAC and SF-36: Instruments for Evaluating the Health-Related Quality of Life of Elderly People with Total Hip Arthroplasty. A Descriptive Study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2015, 133, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Hinman, R.S.; Knox, G.; Spiers, L.; Sumithran, P.; Murphy, N.J.; McManus, F.; Lamb, K.E.; Cicuittini, F.; Hunter, D.J.; et al. Effects of Adding a Diet Intervention to Exercise on Hip Osteoarthritis Pain: Protocol for the ECHO Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelani, M.A.; Marx, C.M.; Humble, S. Are Neighborhood Characteristics Associated With Outcomes After THA and TKA? Findings From a Large Healthcare System Database. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2023, 481, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, L.; Chen, A.F. Patient Satisfaction and Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Review. Arthroplasty 2019, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, D.L.; Dunn, J.A.; Hooper, G. Associations between Pain, Function and Quality of Life after Total Hip Arthroplasty. Int. J. Orthop. Trauma. Nurs. 2024, 54, 101121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K.; Sørensen, O.G.; Hansen, T.B.; Thomsen, P.B.; Søballe, K. Accelerated Perioperative Care and Rehabilitation Intervention for Hip and Knee Replacement Is Effective: A Randomized Clinical Trial Involving 87 Patients with 3 Months of Follow-Up. Acta Orthop. 2008, 79, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giesinger, J.M.; Kuster, M.S.; Behrend, H.; Giesinger, K. Association of Psychological Status and Patient-Reported Physical Outcome Measures in Joint Arthroplasty: A Lack of Divergent Validity. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, U.G.; De Salvatore, S.; Greco, A.; Marino, M.; Santamaria, G.; Piergentili, I.; De Marinis, M.G.; Denaro, V. Influence of Depression and Sleep Quality on Postoperative Outcomes after Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Prospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauß, I.; Steinhilber, B.; Haupt, G.; Miller, R.; Martus, P.; Janßen, P. Exercise Therapy in Hip Osteoarthritis—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2014, 111, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atukorala, I.; Hunter, D.J. A Review of Quality-of-Life in Elderly Osteoarthritis. Expert. Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2023, 23, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paget, L.D.A.; Tol, J.L.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.M.J.; Reurink, G. Health-Related Quality of Life in Ankle Osteoarthritis: A Case-Control Study. Cartilage 2021, 13, 1438S–1444S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.-X.; Yang, X.; Zhao, F.; Ma, J.-Q.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Liang, F.; Zhao, L.; Cai, D.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life and Its Influencing Factors in Chinese with Knee Osteoarthritis. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 2395–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, H.; Guillemin, F.; Pallagi, E.; Fekete, R.; Lippai, Z.; Luterán, F.; Tóth, I.; Tóth, K.; Vallata, A.; Varjú, C.; et al. Evaluation of Osteoarthritis Knee and Hip Quality of Life (OAKHQoL): Adaptation and Validation of the Questionnaire in the Hungarian Population. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. 2020, 12, 1759720X20959570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, D.R.B.; Moça Trevisani, V.F.; Frazao Okazaki, J.E.; Valéria De Andrade Santana, M.; Pereira Nunes Pinto, A.C.; Tutiya, K.K.; Gazoni, F.M.; Pinto, C.B.; Cristina Dos Santos, F.; Fregni, F. Risk Factors of Pain, Physical Function, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Elderly People with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcieszek, A.; Kurowska, A.; Majda, A.; Liszka, H.; Gądek, A. The Impact of Chronic Pain, Stiffness and Difficulties in Performing Daily Activities on the Quality of Life of Older Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuprez, A.; Neuprez, A.H.; Kaux, J.-F.; Kurth, W.; Daniel, C.; Thirion, T.; Huskin, J.-P.; Gillet, P.; Bruyère, O.; Reginster, J.-Y. Total Joint Replacement Improves Pain, Functional Quality of Life, and Health Utilities in Patients with Late-Stage Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis for up to 5 Years. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 39, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hozan, C.T.; Coțe, A.; Bulzan, M.; Szilagy, G. Common Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering for Bone Tissue Regeneration: A Review Article. Pharmacophore 2023, 14, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbø, J.V.; Straume-Næsheim, T.M.; Hallan, G.; Fenstad, A.M.; Sivertsen, E.A.; Årøen, A. Patients with Total Hip Arthroplasty Were More Physically Active 9.6 Years after Surgery: A Case-Control Study of 429 Hip Arthroplasty Cases and 29,272 Participants from a Population-Based Health Study. Acta Orthop. 2024, 95, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajala, M.; Holopainen, R.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kaakinen, P.; Meriläinen, M. A Quasi-experimental Study of Group Counselling Effectiveness for Patient Functional Ability and Quality of Counselling among Patients with Hip Arthroplasty. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 6108–6116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraliov, A.T.; Iacov-Craitoiu, M.M.; Mogoantă, M.M.; Predescu, O.I.; Mogoantă, L.; Crăiţoiu, S. Management and Treatment of Coxarthrosis in the Orthopedic Outpatient Clinic. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2023, 49, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Browne, H.; Mobasheri, A.; Rayman, M.P. What Is the Evidence for a Role for Diet and Nutrition in Osteoarthritis? Rheumatology 2018, 57, iv61–iv74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, A.N.; Vincent, H.K.; Newman, C.B.; Batsis, J.A.; Abbate, L.M.; Huffman, K.F.; Bodley, J.; Vos, N.; Callahan, L.F.; Shultz, S.P. Evidence-Based Dietary Practices to Improve Osteoarthritis Symptoms: An Umbrella Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, T.; Stevens, M.; Van Beveren, J.; Rijk, P.C.; Brouwer, R.; Bulstra, S.; Brouwer, S. Influence of Social Support on Return to Work after Total Hip or Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Prospective Multicentre Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e059225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Population | Tools/Measures | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10-Year natural course of early hip osteoarthritis in middle-aged persons with hip pain: a CHECK study [36] | 588 participants aged 45–65 | Physical exams, clinical criteria for OA | Pain and stiffness increased over 10 years; medication use trends varied based on risk groups. |

| Health-related QoL in patients waiting for major joint replacement [37] | 133 patients awaiting surgery | 15D questionnaire | HRQoL worse than controls; no deterioration while waiting, but BMI and baseline 15D scores influenced admission outcomes. |

| The effect of waiting time on health-related QoL [38] | 312 patients | 15D, HHS, ADL scores | No significant difference in HRQoL based on waiting time. |

| Study | Population | Tools/Measures | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| QoL and functionality after total hip arthroplasty: a long-term follow-up study [33] | 250 patients (11–23 years postop) | SF-36, Harris Hip Score, WOMAC | High satisfaction rates (96%); hip functionality and comorbidities were key determinants. |

| Excellent Functional Outcome and QoL after Primary Cementless THA Using an Enhanced Recovery Setup [49] | 109 patients | Harris Hip Score, WOMAC, EQ-5D | Significant QoL improvements at 4 weeks and 12 months postop. |

| The impact of age and preoperative HRQoL on improvements after THA [31] | 1283 cases | PROMs, EQ-5D | Older patients had better HRQoL improvements; high preoperative HRQoL inhibited further improvement. |

| Study | Population | Etiology | Key Findings | QOL Assessment Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-Year Natural Course of Early Hip Osteoarthritis (CHECK Study) [36] | 588 participants aged 45–65 with hip pain | Not specified | Physical function decreased significantly over 10 years; medication use varied based on radiographic OA (ROA) presence. | WOMAC, EQ-5D |

| Accelerated Perioperative Care and Rehabilitation Intervention [62] | 87 patients, 42 control, 45 interventions | Degenerative OA | QOL gain higher in the intervention group (0.42 vs. 0.26); reduced hospital length of stay. | EQ-5D, WOMAC |

| Age-Related QOL After Total Hip Replacement [43] | 4519 patients | Primary OA | Older patients had less improvement in HRQoL; younger patients showed higher gains post-surgery. | EQ-5D, WOMAC |

| Effect of Nutritional Status on QOL Post-Surgery [42] | 206 THRs implanted in morbidly obese | Primary OA | Preop WOMAC scores were significantly lower in obese patients; postop improvements comparable to non-obese patients. | WOMAC, SF-36 |

| Impact of Social Support on Recovery and QOL [63] | 29 couples | Primary OA | Spousal support led to enhanced recovery and better QOL improvements in social and family activities. | WOMAC, SF-36 |

| Influence of Depression and Sleep Quality on Post-Op Outcomes [64] | 61 patients | End-stage OA | Depression negatively correlated with QOL outcomes; better mental health linked to better recovery. | SF-36, WOMAC |

| Physical Activity and Functional Recovery After THA [40] | 100 patients | Primary OA | Physiotherapy improved functional outcomes significantly in elderly patients. | Harris Hip Score, WHOQOL-BREF |

| Effects of Fasting and Dietary Changes During Rehabilitation [56] | 125 patients | Primary OA | Modified fasting reduced pain and stiffness by 40%; highlighted dietary influence on recovery. | WOMAC |

| Exercise Therapy and QOL Improvements [65] | 225 patients | Primary OA | Exercise adherence associated with better pain management, physical function, and self-reported effect. | WOMAC, SF-36 |

| Impact of Early Rehabilitation on Patient Satisfaction [32] | 147 patients | OA (Not specified) | Early rehabilitation reduced disability; acceptance of disease improved QOL in 95% of cases. | Barthel Index, WHOQOL-BREF, HHS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bulzan, M.; Voiță-Mekeres, F.; Cavalu, S.; Szilagyi, G.; Mekeres, G.M.; Davidescu, L.; Hozan, C.T. Health Status After Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Literature Review. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2025, 12, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms12010035

Bulzan M, Voiță-Mekeres F, Cavalu S, Szilagyi G, Mekeres GM, Davidescu L, Hozan CT. Health Status After Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Literature Review. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2025; 12(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms12010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleBulzan, Mădălin, Florica Voiță-Mekeres, Simona Cavalu, Gheorghe Szilagyi, Gabriel Mihai Mekeres, Lavinia Davidescu, and Călin Tudor Hozan. 2025. "Health Status After Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Literature Review" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 12, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms12010035

APA StyleBulzan, M., Voiță-Mekeres, F., Cavalu, S., Szilagyi, G., Mekeres, G. M., Davidescu, L., & Hozan, C. T. (2025). Health Status After Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Literature Review. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 12(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms12010035