Current Insight into the Dynamics of Secondary Endodontic Infections

Abstract

1. Introduction

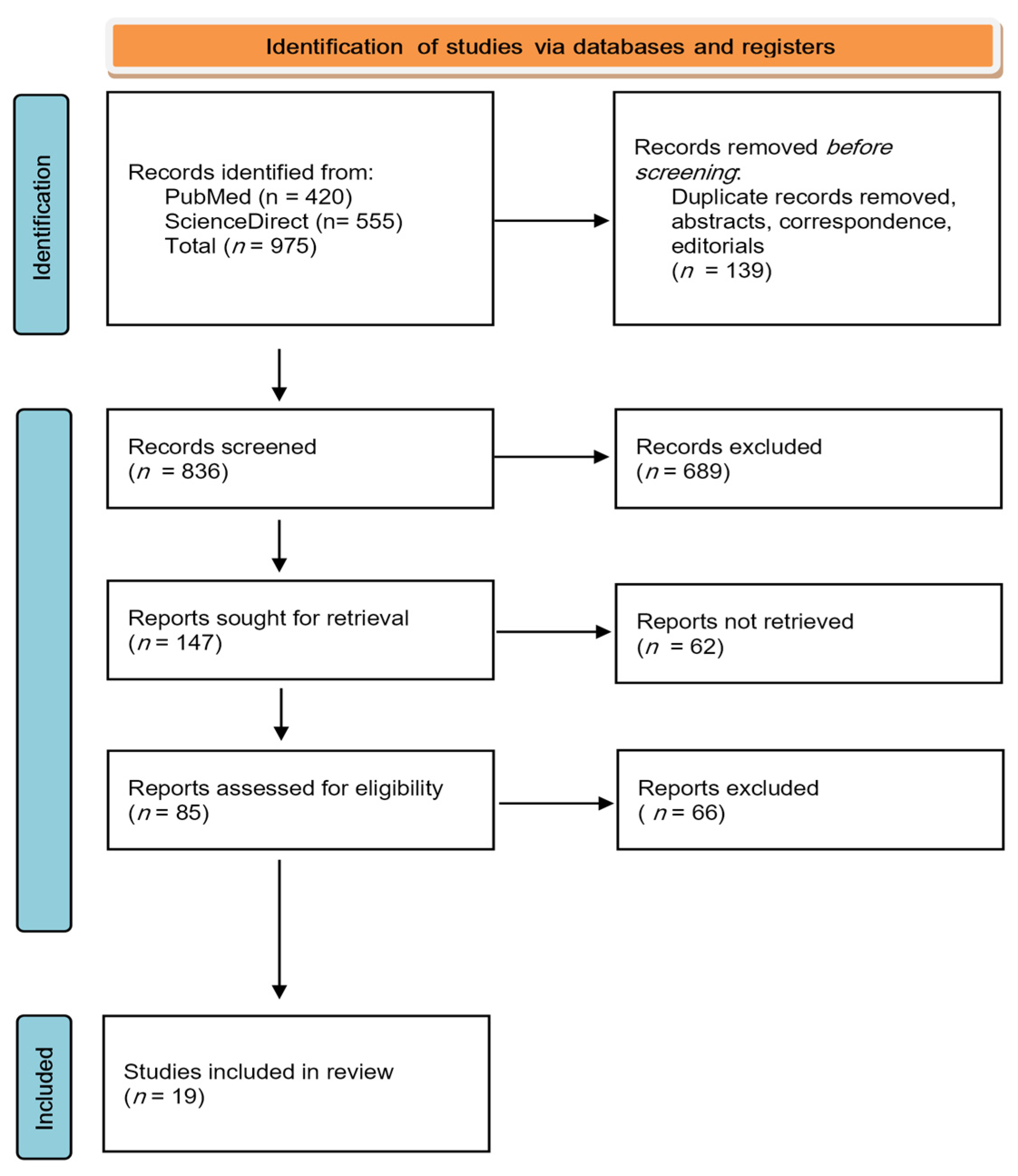

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Question

2.2. Search Strategy

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Quality Assessment

3.2. Summary of Findings

3.3. Interpreting the Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Current Insight into Microbial Colonization of Necrotic Root Canals

4.2. Decipher the Endodontic Microbiome

4.3. Primary Versus Secondary Endodontic Infections

4.3.1. Microbial Communities in Primary Endodontic Infections

4.3.2. Microbial Communities in Secondary Endodontic Infections

4.3.3. Persisting Taxa in Post-Instrumentation Secondary Infections

4.3.4. Putative Correlation Between Root Canal Microbiome and Clinical Symptoms

4.4. Dynamic Transition from Primary to Secondary Endodontic Infection

4.5. Putative Endodontic Pathogens vs. Functional Redundancy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PEI | primary endodontic infection |

| SEI | secondary endodontic infection |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| Sp | species |

| 16S rRNA | 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid |

| EN | Enterococcus faecalis |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| OTU | operational taxonomic units |

| PAP | primary apical periodontitis |

| SAP | symptomatic apical periodontitis |

| FN | Fusobacterium nucleatum |

| PAI | periapical index |

| RAP | refractory apical periodontitis |

References

- Bouillaguet, S.; Manoil, S.; Girard, M.; Louis, J.; Gaia, N.; Leo, S.; Schrenzel, J.; Lazarevic, V. Root microbiota in primary and secondary apical periodontitis. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Y.; Sun, Z.; Ma, H.; Cao, D.; Sun, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhuo, Q.; Tao, R.; Ying, B.; et al. Odontogenic infections in the antibiotic era: Approach to diagnosis, management, and prevention. Infection 2024, 52, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiburcho-Machado, C.S.; Michelon, C.; Zanatta, F.B.; Gomes, M.S.; Marin, J.A.; Bier, C.A. The global prevalence of apical periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 712–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuweiler, D.; Ordinola-Zapata, R.; Dietz, M.; Lima, B.P.; Noblett, W.C.; Staley, C. Microbial diversity in primary endodontic infections: Demographics and radiographic characteristics. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, R.R.; Love, R.M.; Braga, T.; Souza Côrtes, M.I.; Rachid, C.T.C.C.; Rôças, I.N.; Siqueira, J.F. Impact of root canal preparation using two single-file systems on the intra-radicular microbiome of teeth with primary apical periodontitis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coaguila-Llerena, H.; Ordinola-Zapata, R.; Staley, C.; Dietz, M.; Chen, R.; Faria, G. Multispecies biofilm removal by a multisonic irrigation system in mandibular molars. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelakantan, P.; Romero, M.; Vera, J.; Daood, U.; Khan, A.U.; Yan, A.; Cheung, G.S.P. Biofilms in endodontics—Current status and future directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, J.F.; Silva, W.O.; Romeiro, K.; Gominho, L.F.; Alves, F.R.F.; Rộças, I.N. Apical root canal microbiome associated with primary and posttreatment apical periodontitis: A systematic review. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, I.; Mico-Munoz, P.; Giner-Lluesma, T.; Mico-Martinez, P.; Collado-Castellano, N.; Manzano-Saiz, A. Influence of microbiology on endodontic failure. Literature review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2019, 24, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, S.R.; Siqueira, J.F.; Voigt, D.D.; Soimu, G.; Brasil, S.C.; Provenzano, J.C.; Mdala, I.; Alves, A.R.F.; Rộças, I.N. Bacteriologic conditions of the apical root canal system of teeth with and without posttreatment apical periodontitis: A correlative multianalytical approach. J. Endod. 2024, 50, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.H.; Lin, Y.X.; Zhou, L.; Lin, C.; Zhang, L. The immune landscape in apical periodontitis: From mechanism to therapy. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 1526–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordinola-Zapata, R.; Noblett, W.C.; Perez-Ron, A.; Ye, Z.; Vera, J. Present status and future directions of intracanal medicaments. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 613–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonavoglia, A.; Zamparini, F.; Lanave, G.; Pellegrini, F.; Diakoudi, G.; Spinelli, A.; Lucente, M.S.; Camero, M.; Vasinioti, V.I.; Gandolfi, M.G.; et al. Endodontic microbial communities in apical periodontitis. J. Endod. 2023, 49, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Shetty, N.D.; Kamath, D.G. Commensalism of fusobacterium nucleatum—The dilemma. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2024, 28, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korona-Glowniak, I.; Piatek, D.; Fornal, E.; Lukowiak, A.; Gerasymchuk, Y.; Kedziora, A.; Bugla-Ploskinska, G.; Grywalska, E.; Bachanek, T.; Malm, A. Patterns of oral microbiota in patients with apical periodontitis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, J.F.; Rộças, I.N. A critical analysis of research methods and experimental models to study the root canal microbiome. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 46–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Hu, J.; Chen, J.; Zhou, W. High-performing cross-dataset machine learning reveals robust microbiota alteration in secondary apical periodontitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1393108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, R.R.; Braga, T.; Siqueira, J.F.; Rộças, I.N.; da Costa Rachid, C.T.C.; Guimarães Oliveira, A.G.; de Sousa Côrtes, M.I.; Love, R.M. Root canal microbiome associated with asymptomatic apical periodontitis as determined by high-throughput sequencing. J. Endod. 2022, 48, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadainy, H.A.; Abdel-karim, A.H.; Fouad, A.F. Prevalence of Fusobacterium species in endodontic infections detected with molecular methods: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Endod. 2023, 49, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardelo, L.C.L.; Pinheiro, E.T.; Gavini, G.; Prado, L.C.; Romero, R.X.; Gomes, B.P.F.A.; Skelton-Macedo, M.C. Nature and prevalence of bacterial taxa persisting after root canal chemomechanical preparation in permanent teeth: A systematic review. J. Endod. 2022, 48, 572–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, A.; Razi, M.A.; Kundu, M.; Qamar, S.; Chandra, S.; Deep, A. Comparative evaluation of microbial flora of endodontic origin in teeth with endo-perio lesions. J. Pharm. Bioall. Sci. 2024, 16, S856–S858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, J.E.; Stratton, C.W.; Persing, D.H.; Tang, Y.W. Forty years of molecular diagnostics for infectious diseases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022, 60, e0244621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Könönen, E.; Fteita, D.; Gursoy, U.K.; Gursoy, M. Prevotella species as oral residents and infectious agents with potential impact on systemic conditions. J. Oral. Microbiol. 2022, 14, 2079814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, E.T.; Karygianni, L.; Candeiro, G.T.M.; Vilela, B.G.; Dantas, L.O.; Pereira, A.C.C.; Gomes, B.P.F.A.; Attin, T.; Thumheer, T.; Russo, G. Metatranscriptome and resistome of the endodontic microbiome. J. Endod. 2024, 50, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, R.; Liu, T.; Lu, X.; Huang, W.; Guo, L.; Coaggregated, E. faecalis with F.nucleatum regulated environmental stress responses and inflammatory effects. Appl. Microbiol. Technol. 2024, 108, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Dong, P.T.; Cen, L.; Bor, B.; Lux, R.; Shi, W.; Yu, Q.; He, X.; Wu, T. Antagonistic interaction between two key endodontic pathogens Enterococcus faecalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum. J. Oral. Microbiol. 2023, 15, 2149448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, F.A.; Micu, S.I.; Popoiag, R.E.; Musat, M.; Caloian, A.D.; Calu, V.; Constantin, V.D.; Balan, D.G.; Nitipir, C.; Enache, F. Intestinal dysbiosis—A new treatment target in the prevention of colorectal cancer. J. Mind. Med. Sci. 2021, 8, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fässler, D.; Heinken, A.; Hertel, J. Caracterising measures of functional redundancy in microbiome communities via relative entropy. Comp. Str. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 27, 1482–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillingham, M.A.F.; Pruter, H.; Montero, B.K.; Kempenaers, B. The costs and benefits of a dynamic host microbiome. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2025, 40, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.M.; Luo, T.; Lee, K.H.; Guerreiro, D.; Botero, T.M.; McDonald, N.J.; Rickard, A.H. Deciphering endodontic microbial communities by next-generation sequencing. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, J.F.; Rộças, I.N. Present status and future directions: Microbiology of endodontic infections. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastav, S.; Biswas, A.; Anand, A. Interplay of niche and respiratory network in shaping bacterial colonization. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruly, P.C.; Alenezi, H.E.H.M.; Manogue, M.; Devine, D.A.; Dame-Teixeira, N.; Pimentel Garcia, F.C.; Do, T. Residual bacteriome after chemomechanical preparation of root canals in primary and secondary infections. J. Endod. 2022, 48, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waag, C.; Schlaeppi, K.; Banerjee, S.; Kramae, E.E.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Fungal-bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swapna Kumari, K.; Dixit, S.; Gaur, M.; Behera, D.U.; Dey, S.; Sahoo, R.K.; Dash, P.; Subudhi, E. Taxonomic assignment-based genome reconstruction from apical periodontal metagenomes to identify antibiotic resistance and virulence factors. Life 2023, 13, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordinola-Zapata, R.; Costalonga, M.; Nixdorf, D.; Dietz, M.; Schuweiler, D.; Lima, B.P.; Staley, C. Taxonomic abundance in primary and secondary root canal infections. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, K.S.; Chung, J.; Na, H.S. Comparison of the performance of MiSeq and NovaSeq in oral microbiome study. J. Oral. Microbiol. 2024, 16, 2344293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alquria, T.A.; Acharya, A.; Tordik, P.; Griffin, I.; Martinho, F.C. Impact of root canal disinfection on the bacteriome present in primary endodontic infection: A next generation sequencing study. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, J.F.; Antunes, H.S.; Perez, A.R.; Alves, F.R.F.; Mdala, I.; Silva, E.J.N.L.; Belladonna, F.G.; Rộças, I.N. The apical root canal system of teeth with posttreatment apical periodontitis: Correlating microbiologic, tomographic, and histopathologic findings. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoil, D.; Al-Manei, K.; Belibasakis, G.N. A systematic review of the root canal microbiota associated with apical periodontitis: Lessons from next-generation sequencing. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2020, 14, e1900060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito, L.C.N.; Doolittle-Hall, J.; Lee, C.T.; Moss, K.; Bambirra Júnior, W.; Tavares, W.L.F.; Ribeiro Sobrinho, A.P.; Teles, F.R.F. The apical root canal system microbial communities determined by next-generation sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valm, A.M. The structure of dental plaque microbial communities in the transition from health to dental caries and periodontal disease. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 2957–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronzato, J.D.; Davidian, M.E.S.; de Castro, M.; de-Jesus-Soares, A.; Ferraz, C.C.R.; Almeida, J.F.A.; Marciano, M.A.; Gomes, B.P.F.A. Bacteria and virulence factors in periapical lesions associated with teeth following primary and secondary root canal treatment. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 54, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Ma, T.; Ye, M.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hao, P. Microbiota in the apical root canal system of tooth with apical priodontitis. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, C.A.; Garrett, W.S. Fusobacterium nucleatum—Symbiont, opportunist and oncobacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maezono, H.; Klanliang, K.; Shimaoka, T.; Asahi, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Haapasalo, M.; Hayashi, M. Effects of sodium hypochlorite concentration and application time on bacteria in an ex vivo polymicrobial biofilm model. J. Endod. 2024, 50, 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nieuwenhuysen, J.P.; D’Hoore, W.; Leprince, J.C. What ultimately matters in root canal treatment success and tooth preservation: A 25-year cohort study. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 544–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Carrasco, V.; Uroz-Torres, D.; Soriano, M.; Solana, C.; Ruiz-Linares, M.; Garcia-Salcedo, J.A.; Arias-Moliz, M.T. Microbiome in paired root apices and periapical lesions and its associatopn with clinicl signs in persistent apical periodontitis using next-generation sequencing. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persoon, I.F.; Buijs, M.J.; Ozok, A.R.; Crielaard, W.; Krom, B.P.; Zaura, E.; Brandt, B.W. The mycobiome of root canal infections is correlated to the bacteriome. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2017, 21, 871–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliescu, A.A.; Gheorghiu, I.M.; Ciobanu, S.; Roman, I.; Dumitriu, A.S.; Popescu, G.A.D.; Păunică, S. Primary endodontic infections—Key issue in pathogenesis of chronic apical periodontitis. J. Mind. Med. Sci. 2024, 11, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordinola-Zapata, R.; Costalonga, M.; Dietz, M.; Lima, B.P.; Staley, C. The root canal microbiome diversity and function. A whole-metagenome shotgun analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 872–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Yang, Z.; Nie, Y.; Hou, B. Microbial communities in the extraradicular and intraradicular infections associated with persistent apical periodontitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 11, 798367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.H.; Park, O.J.; Yoo, Y.J.; Perinpanayagam, H.; Cho, E.B.; Kim, K.; Park, J.; Noblett, W.G.; Kum, K.Y.; Han, S.H. Microbiota association and profiling of gingival sulci and root canals of teeth with primary or secondary/persistent endodontic infections. J. Endod. 2024, 50, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Tan, X.; Huang, D.; Song, D. Potential relationship between clinical symptoms and the root canal microbiomes of root filled teeth based on the next-generation sequencing. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thammasitboon, K.; Teanpaisan, R.; Pahumunto, N. Prevalence and virulence factors of haemolytic Enterococcus faecalis isolated from root filled teeth associated with periradicular lesions: A laboratory investigation in Thailand. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Moliz, M.T.; Perez-Carrasco, V.; Uroz-Torres, D.; Ramos, J.D.S.; Garcia-Salcedo, J.A.; Soriano, M. Identification of keystone taxa in root canals and periapical lesions of post-treatment endodontic infections: Next generation microbiome research. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Wang, X.W.; Wu, A.K.; Fan, Y.; Friedman, J.; Dahlin, A.; Waldor, M.K.; Weinstock, G.M.; Weiss, S.T.; Liu, Y.Y. Deciphering functional redundancy in the human microbiome. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Moliz, M.T.; Ordinola-Zapata, R.; Staley, C.; Perez-Carrasco, V.; Garcia-Salcedo, J.A.; Uroz-Torres, D.; Soriano, M. Exploring the root canal microbiome in previously treated teeth: A comparative study of diversity and metabolic pathways across two geographical locations. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.R.; Shin, J.; Guevarra, R.B.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.W.; Seol, K.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.B.; Isaacson, R.E. Deciphering diversity indices for a better understanding of microbial communities. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 2089–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonze, D.; Coyte, K.Z.; Lahti, L.; Faust, K. Microbial communities as dynamical systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2018, 44, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudela, H.; Claus, S.P.; Saleh, M. Next generation microbiome research: Identification of keystone species in the metabolic regulation of host-gut microbiota interplay. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 719072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronda, C.; Wang, H.H. Engineering temporal dynamics in microbial communities. Cur.r Opin. Microbiol. 2022, 65, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager-Mair, F.F.; Bloch, S.; Schäffer, C. Glycolanguage of oral microbiota. Mol. Oral. Microbiol. 2024, 39, 291–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboushadi, M.M.; Albelasy, E.H.; Ordinola-Zapata, R. Association between endodontic symptoms and root canal microbiota: A systematic review and meta-analysis of bacteroidetes, spirochaetes and fusobacteriales. Clin Oral Invest 2024, 28, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakovlevic, A.; Duncan, H.F.; Nagendrababu, V.; Jacimovic, J.; Milasin, J.; Dummer, P.M.H. Association between cardiovascular diseases and apical periodontitis: An umbrella review. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 1374–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, E.B.; Gomes, C.C.; Pires, F.R.; Pinto, L.C.; Antunes, L.A.A.; Armada, L. Immunoexpression of bone resorption biomarkers in apical periodontitis in diabetics and normoglycaemics. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagendrababu, V.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Fouad, A.F.; Pulikkotil, S.J.; Dummer, P.M.H. Association between diabetes and the outcome pf root canal treatment in adults: An umbrella review. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cintra, L.T.A.; Gomes, M.S.; da Silva, C.C.; Faria, F.D.; Benetti, F.; Cosme-Silva, L.; Oliveira Samuel, R.; Pinheiro, T.N.; Estrela, C.; Gonzalez, A.C.; et al. Evolution of endodontic medicine: A critical narrative review of the interrelationship between endodontics and systemic pathological conditions. Odontology 2021, 109, 741–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; Gould, K.; Hakan Sen, B.; Jonasson, P.; Cotti, E.; Mazzoni, A.; Sunay, H.; Tjäderhane, L.; Dummer, P.M.H. Antibiotics in endodontics: A review. Int. Endod. J. 2017, 50, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Schlaeppi, K.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Keystone taxa as drivers of microbiome structure and functioning. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunar Silva, I.; Cascales, E. Molecular strategies underlying Porphyromonas gingivalis virulence. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 166836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraga, H.; Sato, T.; Watanabe, K.; Hamada, N.; Tani-Ishii, N. Effect of progression of Fusobacterium nucleatum induced apical periodontitis on the gut microbiota. J. Endod. 2022, 48, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamont, R.J.; Koo, H.; Hajishengallis, G. The oral microbiota: Dynamic communities and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiou, A.C.; van der Waal, S.V.; Buijs, M.J.; Crielaard, W.; Zaura, E.; Brandt, B.W. The endodontic microbiome in relation to circulatory immunologic markers. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 748–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article, Year | Topic | References |

|---|---|---|

| Bouillaguet, S. et al., 2018 Buonavoglia, A. et al., 2023 Nayak, S. et al., 2024 Korona-Glowniak, I. et al., 2021 Siqueira, J.F. et al.,2022 | Current insight into microbial colonization of necrotic root canals | [1,13,14,15,16] |

| Siqueira, J.F. et al.,2024 Li, H. et al., 2024 Amaral, R.R. et al., 2022 Alhadainy, H.A. et al., 2023 | Decipher the endodontic microbiome | [8,17,18,19] |

| Nardelo, L.C.L. et al., 2022 Mahajan, A. et al., 2024 Schmitz, J.E. et.al, 2022 Könönen, E. et al., 2022 | Primary versus secondary endodontic infections | [20,21,22,23] |

| Pinheiro, E.T. et al., 2024 Zhou, J. et al., 2024 Xiang, D. et al., 2023 | Dynamic transition from primary to secondary endodontic infection | [24,25,26] |

| Dumitru, F.A. et al., 2021 Fässler, D. et al., 2025 Gillingham, M.A.F. et al., 2025 | Putative endodontic pathogens vs. functional redundancy | [27,28,29] |

| Current Insight in Microbial Colonization of Infected Root Canals | Microbiome | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEI | SEI | ||

| Etiology | polymicrobial | polymicrobial | [1,13] |

| Most numerous phyla | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria | [13] |

| Most numerous genera | Cutibacterium, Lactobacillus, Pseudomonas, Dialister, Prevotella, and Staphylococcus | Cutibacterium, Prevotella, Atopobium, Capnocytophaga, Fusobacterium, Pseudomonas, Solobacterium and Streptocccus | [13] |

| High frequency | Fusobacterium nucleatum, Parvimonas micra, Porphyromonas endodontalis, Prevotella oris, Slackia exigua, Dialister pneumosintes | Enterococcus faecalis Actinomyces spp., Cutibacterium acnes, Pseudoramibacter alactolyticus, Arachnia propionica, Dialister spp., Fusobacterium nucleatum, Parvimonas micra, Prevotella spp. As-yet-uncultivable or uncharacterized phylotypes may be sometimes dominant | [1,16] |

| Gram-negative | Fusobacterium nucleatum, Dialister spp., Porphyromonas endodontalis, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella spp., Tannerella forsythia, and Treponema spp. | [15,16] | |

| Gram-positive | Enterococcus, Parvimonas micra, Filifactor alocis, Pseudoramibacter alactolyticus, Olsenella uli, Actinomyces spp., Streptococcus spp., Peptostreptococus Propionibacterium spp., Cutibacterium acnes | [15,16] | |

| Positive correlation | Pyramidobacter piscolens, Propionibacterium acnes, Lactobacillus spp., Streptococcus spp., but above all Dialister invisus | [1,15] | |

| Negative correlation | Enterococcus faecalis vs. Fusobacterium nucleatum | [1] | |

| Gene families involvement | LPS biosynthesis | -phosphotransferase system -metabolism of galactose, fructose, amino sugars, nucleotide sugars, and glycerolipids | [1] |

| Co-aggregation of Gram-positive and Gram-negativs | Fusobacterium nucleatum | Fusobacterium nucleatum | [14] |

| Treatment resistant | Enterococcus faecalis, Candida albicans | [15] | |

| Systemic involvement (colorectal cancer) | Fusobacterium nucleatum | [14] | |

| Decipher the Endodontic Microbiome | Microbiome | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEI | SEI | ||

| Most frequent taxa | Pseudoramibacter alactolyticus, Olsenella uli, Fusobacterium spp., Streptococcus spp., Porphyromonas endodontalis, Prevotella spp., Actinomyces spp., Parvimonas micra, Treponema denticola, Synergistetes spp. and as-yet-uncharacterized taxon | Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Fusobacterium, Actinomyces, Pseudoramibacter, Pseudomonas, Propionibacterium. Enterococcus faecalis, Cutibacterium acnes, Delftia acidovorans | [8] |

| The high-performing machine learning models revealed in SEIs the disease signature and enriched metabolic pathways (phosphotransferase system and peptidoglycans biosynthesis) | [17] | ||

| Comparing PEIs and SEIs, it was concluded that a small number of pathogens have a prevailing position in disease development | [17] | ||

| In SEIs, both alpha and beta biodiversity of microbiota are highly correlated with the progression of periapical lesions. | [17] | ||

| Currently, Enterococcus faecalis, Cutibacterium acnes, and Delftia acidovorans are judged as main participating bacteria in failed endodontic treatments. | [17] | ||

| Delftia acidovorans is also persistent in root canals in post-treatment SEIs and is also regarded as a crucial contributor to SEI progression. | [17] | ||

| The shift from PEI to SEI is rather the consequence of microbial imbalance which results in facilitating a small amount of number of bacteria to dominate and trigger a SEI | [17] | ||

| High-throughput sequencing technology underscored the general complexity of infected root canal microbiome as well as its heterogeneity that characterizes individual cases | [18] | ||

| In SEIs, the large older periapical lesions had a higher number of species but the microbial diversity was not significantly different compared to incipient lesions | [18] | ||

| In large lesions the highest prevalence proved a previously uncultivated but still unnamed and uncharacterized taxon Bacteroidaceae (G-1) bacterium HMT 272 | [18] | ||

| The prevalence of Fusobacterium nucleatum in PEIs ranged from 3 to 100%. Its detected subspecies were mainly Fusobacterium nucleatum ssp. nucleatum, followed to a lesser extent by Fusobacterium nucleatum ssp. polymorphum, Fusobacterium nucleatum ssp. vicentii, and Fusobacterium nucleatum ssp. periodonticum | [19] | ||

| Despite the low proportion in SEIs, by association with other members of the community Fusobacterium nucleatum proved to enhance the microbial pathogenicity of Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella nigrescens, P.gingivalis, P.endodontalis, Peptostreptococcus micros, Tannerella forsythia, Treponema denticola, and Streptococcus sp. | [19] | ||

| Currently, present new microbial communities are present in SEIs, but no significant difference was found between PEIs and SEIs regarding the prevalence of Fusobacterium nucleatum | [19] | ||

| Generation | Type | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| First generation | Microbiological methods (open ended) | Culture studies |

| Second generation | Molecular principles of identification (closed ended) | Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (whole genomic probes) |

| Third generation | Molecular principles of identification (open ended) | Open-ended DNA-based assays |

| Fourth generation | Molecular principles of identification (closed ended) | PCR, reverse-capture checkerboard hybridization and microarrays |

| Fifth generation | Molecular principles of identification (open ended) | NGS (next-generation sequencing) Whole Genomic Sequencing Meta-transcriptomics |

| Generation | Methods | Advantages | Limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| First generation | Culture studies | - identifying the main cultivable bacterial species - identifying the susceptibility to customary antimicrobial/antibiotics used in endodontic treatment | - they fail to evaluate the multispecies components in biofilms - they fail to unveil the non-cultivable bacteria |

| Second generation | Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (whole genomic probes) | - more sensitive and specific in detecting particular taxa - identifying difficult-to-grow bacteria - mainly proficient in disclosing the complexity and abundance of microbial communities | they require specific primers for increasing specific microorganisms in demand |

| Third generation | Open-ended DNA-based assays | - more sensitive and specific in detecting particular taxa - enable to distinguish at least the most dominant taxa/all of them (cultivable and as-yet-uncultivable/difficult-to-culture microorganisms) - outlining the profile of endodontic microbiome | they recognized merely the dominant bacterial species |

| Fourth generation | PCR, reverse-capture checkerboard hybridization and microarrays | - more sensitive and specific in detecting particular taxa - identifying as-yet-uncultivable/difficult-to-culture bacteria | they can be altered by different technique aspects (differences in DNA extraction methods, preferential DNA amplification) |

| Fifth generation | Next-generation sequencing (NGS) Whole genomic sequencing and meta-transcriptomics | - more sensitive and specific in detecting particular taxa - identifying diversity and complexity of endodontic microbiome -identifying a large number of scarce unexpected microbial species - identifying microbiota interactions - identifying functional pathways that support initiation/progress of apical periodontitis - systematically quantifying microbiome large-scale data - identifying pathogenic consequences | they can be just screening tool for endodontic microbiome regarding the dynamics of endodontic infections - higher cost - lack standardization - require specialized equipment -require specific skills |

| Primary Versus Secondary Endodontic Infections | Microbiome | References |

|---|---|---|

| In descending order in post-treatment, SEIs were found in 8 bacterial phyla (Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, Spirochaetes, Synergistetes, Saccharibacteria) | [20] | |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum and Leptotrichia buccalis, as main members of the phylum Fusobacteria are among the most abundant species of SEIs | [20] | |

| Some difficult-to-culture members of Firmicutes (Dialister sp., Solobacterium moorei, Pseudoramibacter alactolyticus, Filifactor alocis) were identified given the current molecular methods, presuming a possible pathogenic role | [20] | |

| Usually Dialister sp., Pseudoramibacter alactolyticus, and Filifactor alocis are lower in post-treatment SEIs than in PEIs, in contrast to Solobacterium moorei whose increase in SEIs presumes a putative antimicrobial resistance | [20] | |

| Bacterioidetes have an important role in root canal infections as modulate the activity of anaerobic bacteria and support the pathogenicity | [20] | |

| Bacteroidaceae [G-1] bacterium HMT 272, one of its members usually found in PEIs is significantly reduced in post-treatment SEIs proving to be highly susceptible to endodontic management | [20] | |

| The periodontal endodontic lesions are of polymicrobial etiology | [21] | |

| The highest frequency in periodontal endodontic lesions was recorded in descending order for Porphyromonas gingivlis, Treponema denticola, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Streptococcus mutans, Actinomyces naeslundi, Prevotella intermedia, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, and Enterococcus faecalis | [21] | |

| The genetic and currently genomic/multi-omic knowledge re-characterize the information delivered by microbiological laboratories | [22] | |

| Sequencing detects a pathogen and simultaneously characterizes its identity (diagnostic metagenomics) | [22] | |

| Pathobiome view of disease is based on host-microbe relationship at the physical, metabolic, and inflammatory level falling outside Koch’s criteria | [22] | |

| Patient’s microbiome allows the way to personalized medicine | [22] | |

| Some Prevotella species are true commensals, but some are potential pathobionts within dysbiotic biofilms in susceptible hosts (Prevotella baroniae, Prevotella oris, Prevotella multissacharivorax) contributing to root canal infections | [23] | |

| In pulp necrosis of primary teeth were found Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella nigrescens, and Prevotella denticola | [23] | |

| In SEIs with periapical lesions, including radicular cysts, Prevotella baroniae, Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella buccae, Prevotella multissacharivorax were frequently found | [23] | |

| A dysbiotic shift in biofilms occurs subsequent to an environmental change | [23] | |

| Prevotella species can contribute to microbial dysbiosis and inflammation-regulated periapical tissue destruction | [23] | |

| As immunostimulatory bacteria Prevotella species may play a role as potential pathobionts or pathogens | [23] | |

| Dynamic Transition from Primary to Secondary Endodontic Infections | Microbiome | References |

|---|---|---|

| High-throughput sequencing enhanced the knowledge of the microbial communities in endodontic infections relying on 16S rRNA screening | [24] | |

| Metatranscriptomics displayed the activity of potential endodontic pathogens | [24] | |

| A mixed analysis of 16S rRNA genes (DNA) and transcripts (RNA) of microbial communities proved that transcriptionally active was only a part of its members | [24] | |

| Dominant phyla are Proteobcteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria | [24] | |

| Non-dominant phyla are Fusobacteria, Spirochaetes, and Synergistetes | [24] | |

| Among the top 10 species were found obligate anaerobes (Gram-negative Capnocytophaga sp. oral taxon 323, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella oris, Tannerella forsythia, Tannerella sp. oral taxon HOT-286 as well as Gram-positive Olsenaella uli, Parvimonas micra) | [24] | |

| Transcripts encoding moonlighting proteins are highly expressed resulting in potential effect on bacterial adhesion, biofilm formation, host defense evasion, and induction of periapical inflammation | [24] | |

| The abundance of transcripts encoding moonlighting proteins may suggest a putative role in pathogenesis of periapical lesions | [24] | |

| Streptococcus faecalis survives in environmental stress either separate or in coaggregation with Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. polymorphum | [25] | |

| Coaggregation of Streptococcus faecalis with Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. polymorphum increased its resistance to alkaline, hypertonic, starvation, and antibiotic challenges. | [25] | |

| Due to coaggregation of Streptococcus faecalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. polymorphum changed its gene transcription involved in amino acid metabolism, transporter proteins, lipopolysaccharides metabolism, and biofilm formation | [25] | |

| Coaggregation of Streptococcus faecalis with Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. polymorphum induced macrophages apoptosis and reduced the pro-inflammatory response | [25] | |

| Coaggregation of Streptococcus faecalis with Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. polymorphum helps both of them engulfed by macrophages helping the Streptococcus faecalis survival within the cells | [25] | |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum and Enterococcus faecalis are associated with root canals infections | [26] | |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum is more abundant in PEIs and Enterococcus faecalis in SEIs | [26] | |

| Enterococcus faecalis physically binds to Fusobacterium nucleatum either in planktonic or in biofilm status | [26] | |

| The physical binding of Enterococcus faecalis with Fusobacterium nucleatum requires the galactose-inhibitable adhesion-encoding gene F.nucleatum fap2 | [26] | |

| Enterococcus faecalis exhibits a killing effect against Fusobacterium nucleatum by generating an acidic milieu and hydrogen peroxide | [26] | |

| Putative Endodontic Pathogens Versus Functional Redundancy | Microbiome | References |

|---|---|---|

| Metagenome sequencing reveals bacterial composition, host interactions and taxonomic alterations by analyzing the genetic and metabolic profile of infected root canals microbiome | [27] | |

| More than 70% of human microbiome is located in colon. Within the gut microbiome it was proved that over 90% of microbiota is represented by Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes | [27] | |

| Dysbiosis within the gut microbiome may be associated within colorectal cancer | [27] | |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum was identified in large amounts in colon cancerous tissue compared to neighboring healthy tissue | [27] | |

| Functional redundancy is the core of relationship between high diversity of endodontic microbiome and human health | [28] | |

| The concept of functional redundancy in microbial communities enables the understanding of how microbiota diversity modulates the complexity of functions expressed by endodontic microbiome | [28] | |

| Based on functional redundancy it can be explained how two microbiomes may strongly diverge in species diversity but be for the most part comparable in functions | [28] | |

| Low functional redundancy may be associated with a extremely diverse microbial community compared to an intense functional redundancy expressed by a reduced species diversity | [28] | |

| The key to host health is a stable microbiome, able to display both resistance and resilience against environmental perturbations | [29] | |

| Microbiome stability presumes the chance of microbial communities to adopt multiple dynamic states | [29] | |

| In case of ecological perturbation in infected root canals, the microbial community either returns to its initial homeostatic status or switch to an alternative status, which as previously may be homeostatic or is converted into dysbiotic | [29] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iliescu, A.A.; Gheorghiu, I.M.; Ciobanu, S.; Roman, I.; Dumitriu, A.S.; Păunică, S. Current Insight into the Dynamics of Secondary Endodontic Infections. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2025, 12, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms12010028

Iliescu AA, Gheorghiu IM, Ciobanu S, Roman I, Dumitriu AS, Păunică S. Current Insight into the Dynamics of Secondary Endodontic Infections. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2025; 12(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms12010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleIliescu, Alexandru Andrei, Irina Maria Gheorghiu, Sergiu Ciobanu, Ion Roman, Anca Silvia Dumitriu, and Stana Păunică. 2025. "Current Insight into the Dynamics of Secondary Endodontic Infections" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 12, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms12010028

APA StyleIliescu, A. A., Gheorghiu, I. M., Ciobanu, S., Roman, I., Dumitriu, A. S., & Păunică, S. (2025). Current Insight into the Dynamics of Secondary Endodontic Infections. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 12(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms12010028