The Relationship Between Quality of Life and Functionality in Patients with Schizophrenia—A Preliminary Report

Abstract

:Introduction

Materials and Methods

Results

Discussions

Conclusions

Highlights

- ✓

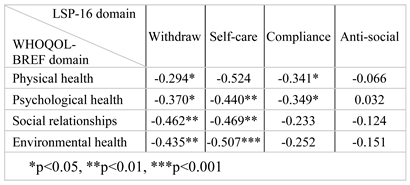

- Lower quality of life was associated with increased disability in patients with schizophrenia.

- ✓

- Satisfaction with social relationships was associated with a lower degree of withdrawal and better self-care performance.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest disclosure

Acknowledgments

References

- World Health Organization. Schizophrenia. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news- room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [CrossRef]

- Clow, B. 'Burden of disease': What it means and why it matters. Available online: https://evidencenetwork.ca/ burden-of-disease-what-it-means-and-why-it-matters/ (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Lajoie, J. Understanding the measurement of global burden of disease. Available online: https://nccid.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/03/Global_Burden_Diseas e_Influenza_ENG.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017, 390, 1211–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettunen, J.; Immonen, J.; McGrath, J.; Isohanni, M.; Jääskeläinen, E. F128. The age of onset of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bulletin. 2018, 44 (Suppl. 1), S270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępnicki, P.; Kondej, M.; Kaczor, A.A. Current Concepts and Treatments of Schizophrenia. Molecules. 2018, 23, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R.S.; Sommer, I.E.; Murray, R.M.; et al. Schizophrenia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015, 1, 15067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karow, A.; Wittmann, L.; Schöttle, D.; Schäfer, I.; Lambert, M. The assessment of quality of life in clinical practice in patients with schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2014, 16, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum, M.Y.; Ho, N.F.; Sim, K. Cross diagnostic comparisons of quality of life deficits in remitted and unremitted patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2015, 168, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.Y.; Migliorini, C.; Huang, Z.H.; et al. Quality of life in patients with schizophrenia: A 2-year cohort study in primary mental health care in rural China. Front Public Health. 2022, 10, 983733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, J.; Villacrés, L.; Rosado, D.; Loor, E. Cognitive Deterioration and Quality of Life in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Single Institution Experience. Cureus. 2020, 12, e6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, C.S.; Caiaffa, W.T.; Bandeira, M.; Siqueira, A.L.; Abreu, M.N.; Fonseca, J.O. Factors associated with low quality of life in schizophrenia. Cad Saude Publica. 2005, 21, 1338–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fan, X.W.; Zhao, X.D.; Zhu, B.G.; Qin, H.Y. Correlation Analysis of the Quality of Family Functioning and Subjective Quality of Life in Rehabilitation Patients Living with Schizophrenia in the Community. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, H.T.; Panatik, S.A.; Nabeel, T.; et al. Observed Social Support and Willingness for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020, 13, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulon, N.; Godin, O.; Bulzacka, E.; et al. Early and very early-onset schizophrenia compared with adult-onset schizophrenia: French FACE-SZ database. Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Immonen, J.; Jääskeläinen, E.; Korpela, H.; Miettunen, J. Age at onset and the outcomes of schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2017, 11, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, D.; Girma, S.; Abdeta, T. Quality of life and its association with current substance use, medication non-adherence and clinical factors of people with schizophrenia in Southwest Ethiopia: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020, 18, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. ICD-10 Classifications of Mental and Behavioural Disorder: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrman, H.; Hawthorne, G.; Thomas, R. Quality of life assessment in people living with psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002, 37, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Expósito, L.; Amador-Campos, J.A.; Gómez-Benito, J.; Lalucat-Jo, L. Research Group on Severe Mental Disorder. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale Brief Version: a validation study in patients with schizophrenia. Qual Life Res. 2011, 20, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlim, M.T.; Pavanello, D.P.; Caldieraro, M.A.; Fleck, M.P. Reliability and validity of the WHOQOL BREF in a sample of Brazilian outpatients with major depression. Qual Life Res. 2005, 14, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, S. World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Scale (WHOQOL-BREF): Analyses of Their Item Response Theory Properties Based on the Graded Responses Model. Iran J Psychiatry. 2010, 5, 140–153. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, G.; Rosen, A.; Emdur, N.; Hadzi-Pavlov, D. The Life Skills Profile: psychometric properties of a measure assessing function and disability in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991, 83, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, P.M.; Harris, M.G.; Coombs, T.; Pirkis, J.E. A systematic review of clinician-rated instruments to assess adults' levels of functioning in specialised public sector mental health services. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017, 51, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network. Abbreviated Life Skills Profile (LSP-16). Available online: https://www.amhocn.org/sites/ default/files/publication_files/life_skills_profile_-16.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Li, Y.; Hou, C.L.; Ma, X.R.; et al. Quality of life in Chinese patients with schizophrenia treated in primary care. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 254, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Zeng, L.N.; Zong, Q.Q.; et al. Quality of life in Chinese patients with schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 268, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.; Naber, D. Current issues in schizophrenia: overview of patient acceptability, functioning capacity and quality of life. CNS Drugs. 2004, 18 (Suppl 2), 5–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eack, S.M.; Newhill, C.E. Psychiatric symptoms and quality of life in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2007, 33, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alptekin, K.; Erkoç, S.; Göğüş, A.K.; et al. Disability in schizophrenia: clinical correlates and prediction over 1-year follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 2005, 135, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.D.; Strassnig, M. Predicting the severity of everyday functional disability in people with schizophrenia: cognitive deficits, functional capacity, symptoms, and health status. World Psychiatry. 2012, 11, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, G.M.; Legas, G.; Azale, T.; Abera, M.; Asnakew, S. The magnitude of disability in patients with schizophrenia in North West Ethiopia: A multicenter hospital-based cross-sectional study. Heliyon. 2021, 7, e07053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.T.; Park, E.C.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.J.; Park, S. Is marital status associated with quality of life? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defar, S.; Abraham, Y.; Reta, Y.; et al. Health related quality of life among people with mental illness: The role of socio-clinical characteristics and level of functional disability. Front Public Health. 2023, 11, 1134032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manickam, L.S.; Chandran, R.S. Life skills profile of patients with schizophrenia and its correlation to a feeling of rejection among key family carers. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005, 47, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Wang, S.; Bi, J.; et al. Gender differences in socio-demographics, clinical characteristic and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia: A community-based study in Shenzhen. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2021, 13, e12446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kujur, N.S.; Kumar, R.; Verma, A.N. Differences in levels of disability and quality of life between genders in schizophrenia remission. Ind Psychiatry J. 2010, 19, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.H.; Karkhaneh Yousefi, M. Quality of Life and GAF in Schizophrenia Correlation Between Quality of Life and Global Functioning in Schizophrenia. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2011, 5, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Galuppi, A.; Turola, M.C.; Nanni, M.G.; Mazzoni, P.; Grassi, L. Schizophrenia and quality of life: how important are symptoms and functioning? Int J Ment Health Syst. 2010, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, R.M.; Malla, A.K.; McLean, T.; et al. The relationship of symptoms and level of functioning in schizophrenia to general wellbeing and the Quality of Life Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000, 102, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandrini, M.; Lançon, C.; Fond, G.; et al. A structural equation modelling approach to explore the determinants of quality of life in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016, 171, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertekin Pinar, S.; Sabanciogullari, S. The relationship between functional recovery and quality of life in patients affected by schizophrenia and treated at a community mental health center in Turkey. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2020, 56, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Mann, F.; Wang, J.; et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing subjective and objective social isolation among people with mental health problems: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 839–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissos, S.; Balanzá-Martinez, V.; Dias, V.V.; Carita, A.I.; Figueira, ML. Is personal and social functioning associated with subjective quality of life in schizophrenia patients living in the community? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011, 261, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender, N (%) | |

| 31 (66) |

| 16 (34) |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 38.32±12.32 |

| Living area, N (%) | |

| 38 (80.85) |

| 9 (19,14) |

| Level of education, N (%) | |

| 10 (21.27) |

| 22 (46.8) |

| 15 (31.91) |

| Marital status, N (%) | |

| 38 (80.85) |

| 0 (0) |

| 5 (10.63) |

| 4 (8.51) |

| Employment status, N (%) | |

| 22 (48.8) |

| 4 (8.51) |

| 1 (2.12) |

| 20 (42.55) |

| Physical chronic comorbidity, N (%) | |

| 13 (27.65) |

| 34 (72.34) |

| Duration of illness (years), mean±SD | 13.45±10.51 |

| Age at illness onset (years), mean±SD | 24.83±7.65 |

| Mean | SD | |

| WHOQOL-BREF domain (transformed scores) | ||

| 50.53 | 21.25 |

| 54.17 | 20.49 |

| 34.75 | 23.72 |

| 52.66 | 21.19 |

| LPS-16 total score | 19.47 | 8.937 |

| LSP-16 domain | ||

| 5.149 | 3.290 |

| 7.638 | 3.467 |

| 3.255 | 2.515 |

| 3.426 | 2.483 |

| WHOQOL-BREF | |||||

| Duration of illness | Physical health | Psychological health | Social relationships | Environmental Health | |

| LPS-16 total score | 0.1614 | -0.426** | -0.396** | -0.452** | -0.470*** |

| **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 | |||||

|

© 2023 by the author. 2023 Vlad Dionisie, Mihnea Costin Manea, Mirela Manea, Lavinia Steluta Bonciu, Sorin Riga, Maria Gabriela Puiu

Share and Cite

Dionisie, V.; Manea, M.C.; Mirela, M.; Bonciu, L.S.; Riga, S.; Puiu, M.G. The Relationship Between Quality of Life and Functionality in Patients with Schizophrenia—A Preliminary Report. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2023, 10, 106-112. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1380

Dionisie V, Manea MC, Mirela M, Bonciu LS, Riga S, Puiu MG. The Relationship Between Quality of Life and Functionality in Patients with Schizophrenia—A Preliminary Report. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2023; 10(1):106-112. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1380

Chicago/Turabian StyleDionisie, Vlad, Mihnea Costin Manea, Manea Mirela, Lavinia Steluta Bonciu, Sorin Riga, and Maria Gabriela Puiu. 2023. "The Relationship Between Quality of Life and Functionality in Patients with Schizophrenia—A Preliminary Report" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 10, no. 1: 106-112. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1380

APA StyleDionisie, V., Manea, M. C., Mirela, M., Bonciu, L. S., Riga, S., & Puiu, M. G. (2023). The Relationship Between Quality of Life and Functionality in Patients with Schizophrenia—A Preliminary Report. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 10(1), 106-112. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1380