Characterizing the Bone Marrow Environment in Advanced-Stage Myelofibrosis during Ruxolitinib Treatment Using PET/CT and MRI: A Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Aim

2.2. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.3. Study Protocol

2.3.1. Study Procedures

2.3.2. Conventional Evaluation

2.3.3. Imaging Protocol

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Conventional Response Evaluations

3.3. Imaging Results

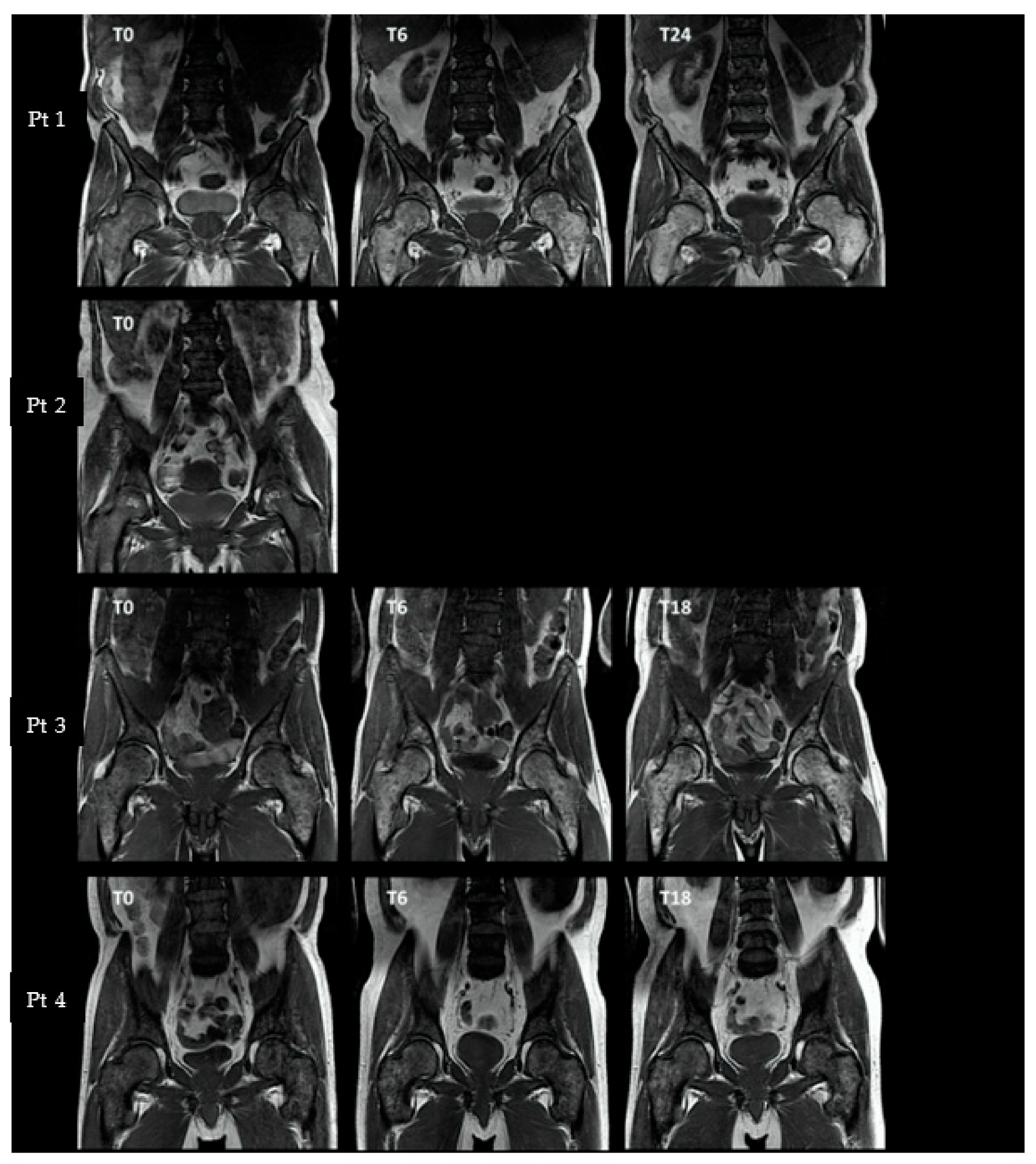

3.3.1. Axial and Proximal Femoral T1-Weighted MRI

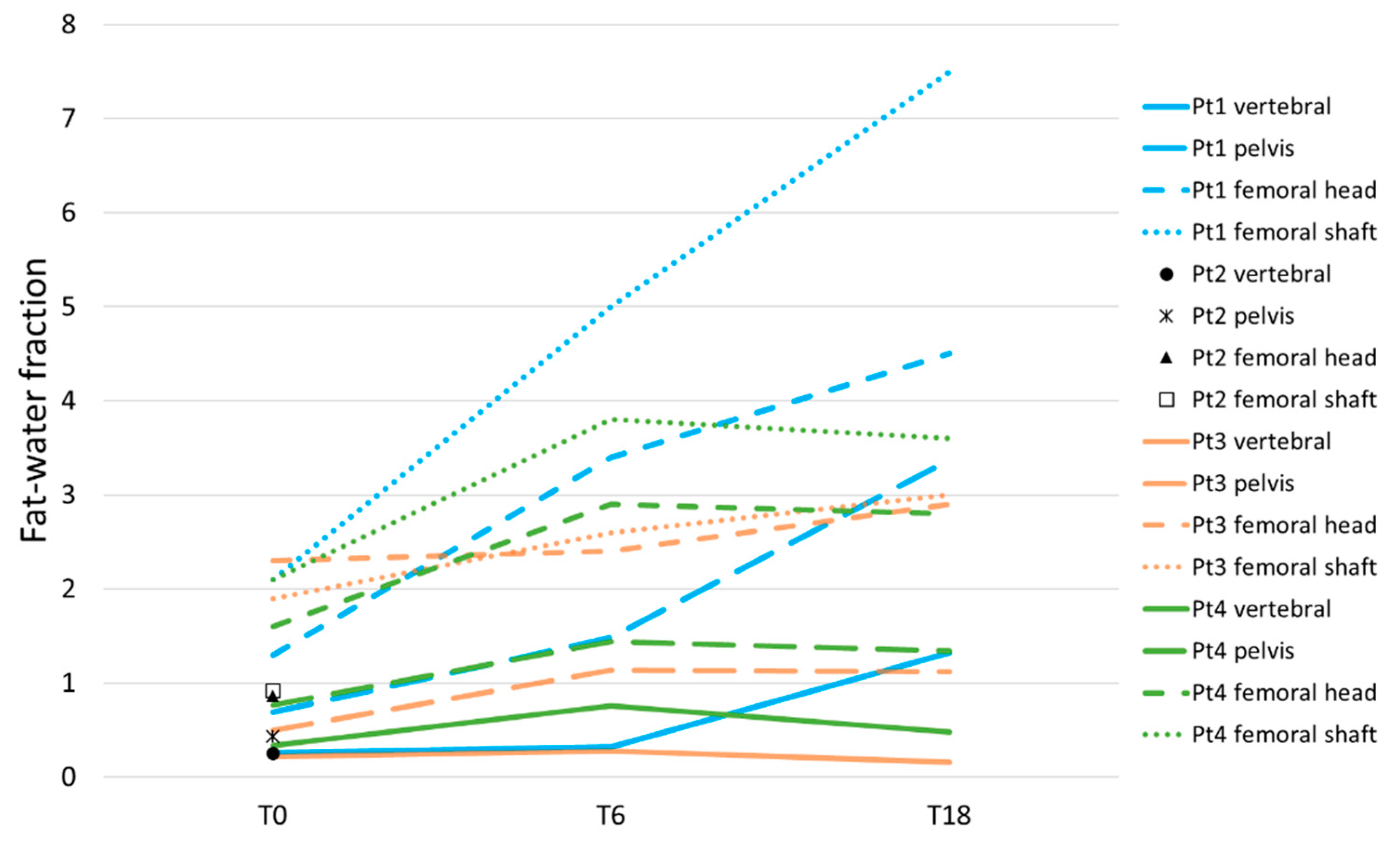

3.3.2. Axial and Proximal Femoral Dixon

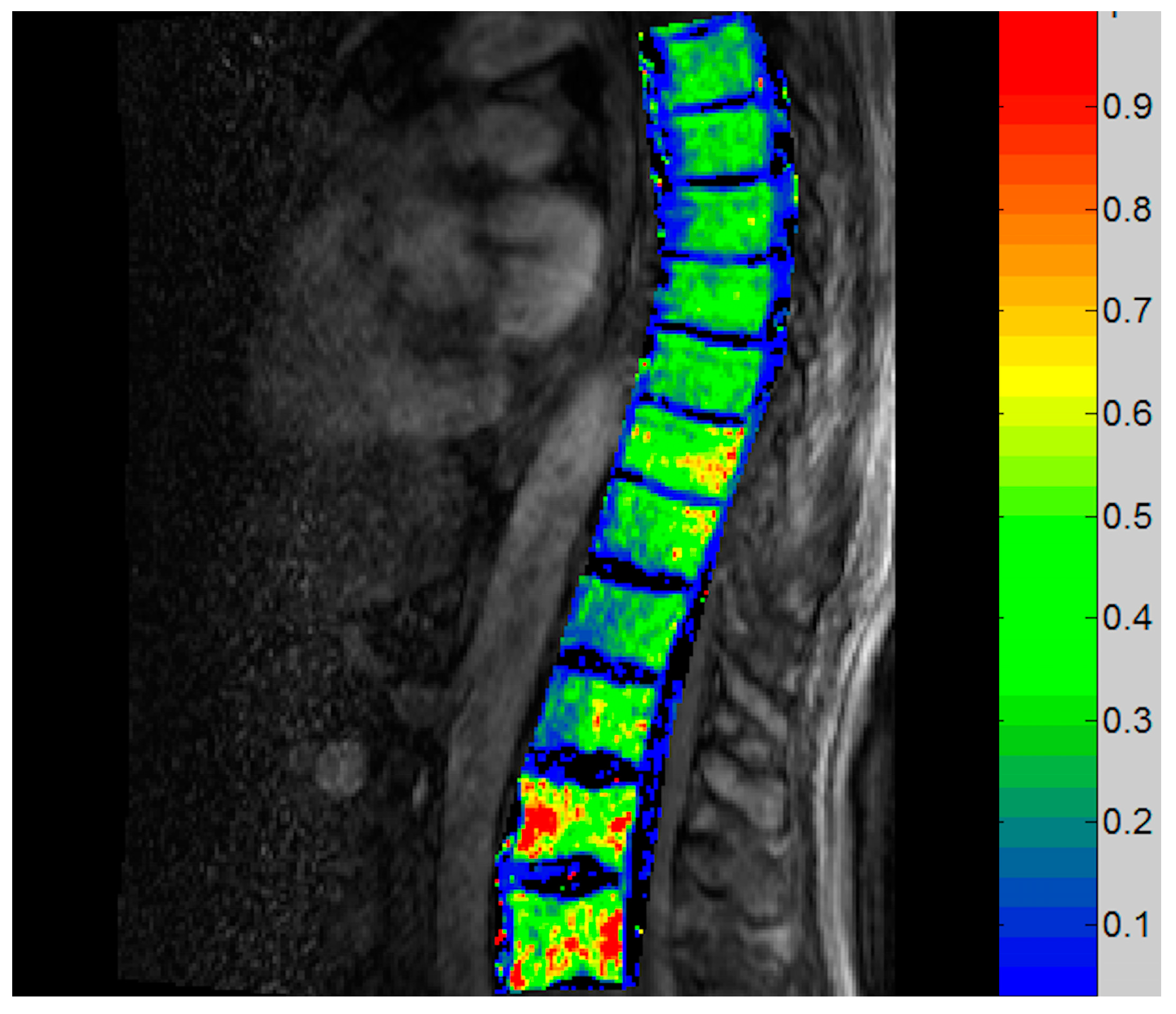

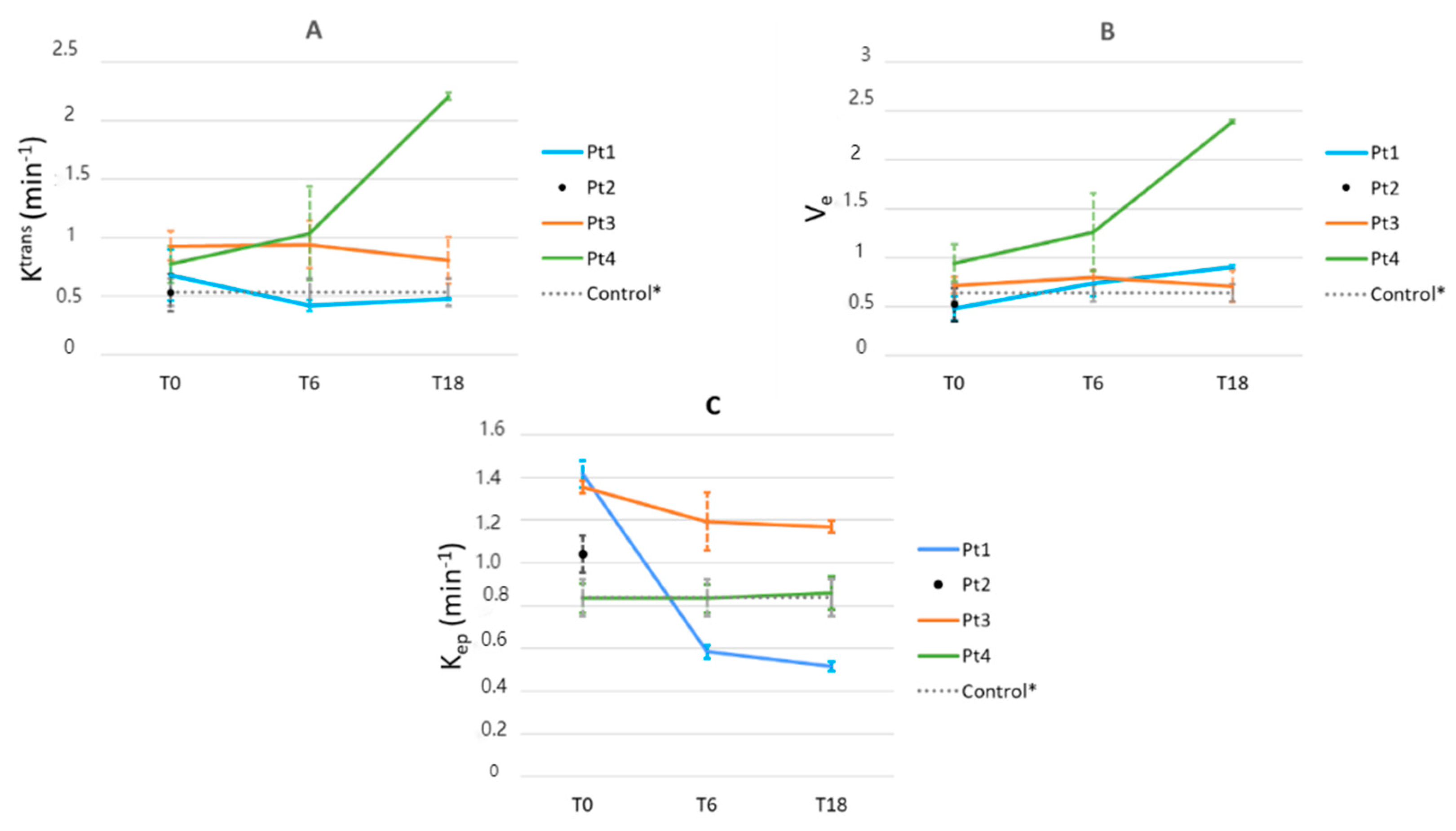

3.3.3. Vertebral DCE-MRI

3.3.4. Vertebral Blood Flow as Measured by [15O]Water PET

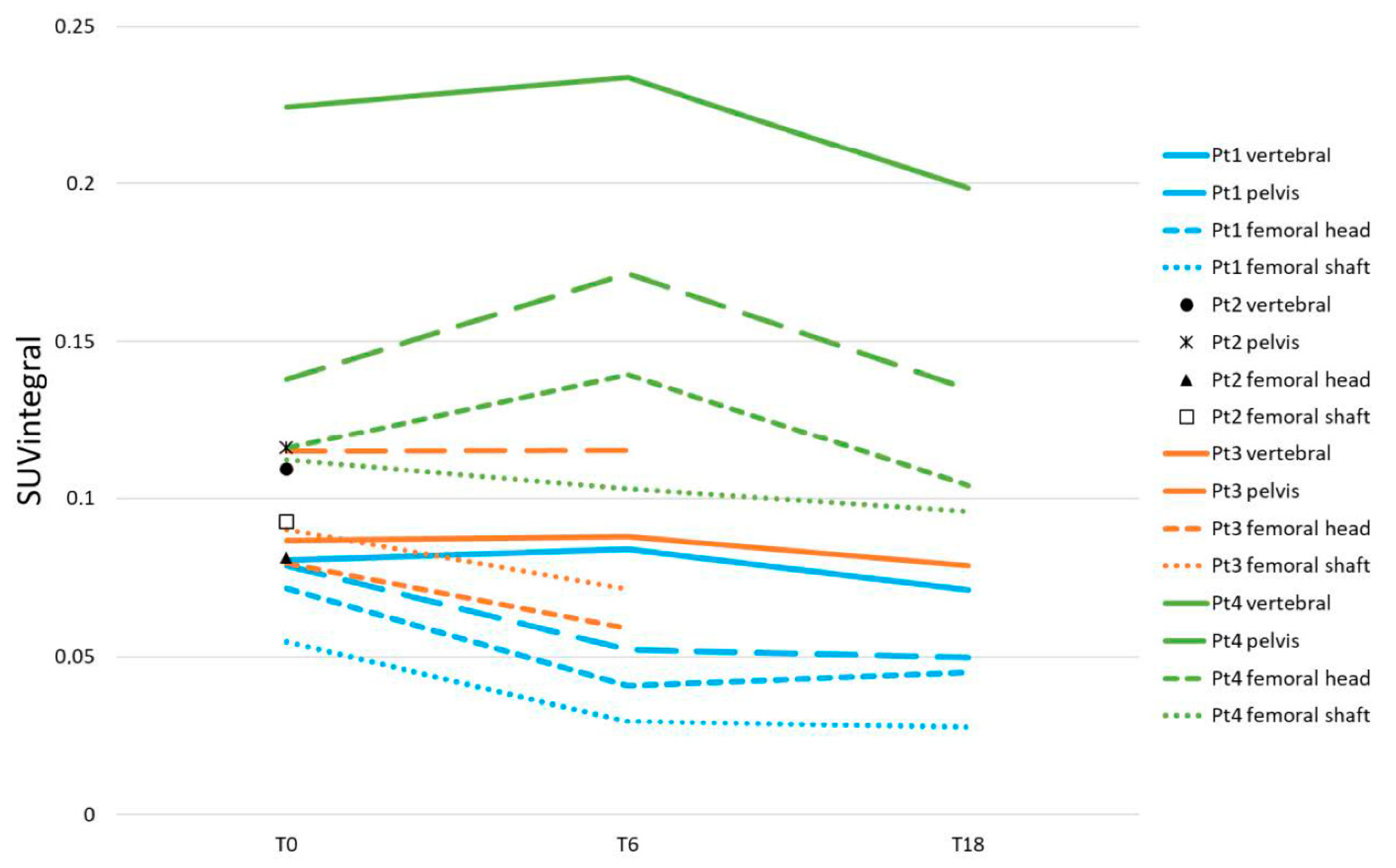

3.3.5. Axial and Femoral [18F]NaF Uptake

3.4. Comparison of Histopathology and Imaging Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mesa, R.A.; Silverstein, M.N.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Wollan, P.C.; Tefferi, A. Population-based incidence and survival figures in essential thrombocythemia and agnogenic myeloid metaplasia: An Olmsted County Study, 1976–1995. Am. J. Hematol. 1999, 61, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, O.; Loch, G.; Schade, U.; Busche, G.; Wasielewski, R.; Wiese, B.; Kreipe, H. Osteosclerosis in advanced chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis is associated with endothelial overexpression of osteoprotegerin. Br. J. Haematol. 2005, 130, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch, H.C. The role of cytokines in the initiation and progression of myelofibrosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013, 24, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahr, A.A.; Salama, M.E.; Carreau, N.; Tremblay, D.; Verstovsek, S.; Mesa, R.; Hoffman, R.; Mascarenhas, J. Bone marrow fibrosis in myelofibrosis: Pathogenesis, prognosis and targeted strategies. Haematologica 2016, 101, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward, H.P.; Block, M.H. The natural history of agnogenic myeloid metaplasia (AMM) and a critical evaluation of its relationship with the myeloproliferative syndrome. Medicine 1971, 50, 357–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekovic, D.; Gotic, M.; Skoda, R.; Beleslin-Cokic, B.; Milic, N.; Mitrovic-Ajtic, O.; Nienhold, R.; Sefer, D.; Suboticki, T.; Buac, M.; et al. Bone marrow microvessel density and plasma angiogenic factors in myeloproliferative neoplasms: Clinicopathological and molecular correlations. Ann. Hematol. 2017, 96, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvasnicka, H.M.; Thiele, J. Bone marrow angiogenesis: Methods of quantification and changes evolving in chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Histol. Histopathol. 2004, 19, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, F.; Dupriez, B.; Pereira, A.; Passamonti, F.; Reilly, J.T.; Morra, E.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Mesa, R.A.; Demory, J.L.; Barosi, G.; et al. New prognostic scoring system for primary myelofibrosis based on a study of the International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment. Blood 2009, 113, 2895–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangat, N.; Caramazza, D.; Vaidya, R.; George, G.; Begna, K.; Schwager, S.; Van Dyke, D.; Hanson, C.; Wu, W.; Pardanani, A.; et al. DIPSS plus: A refined Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System for primary myelofibrosis that incorporates prognostic information from karyotype, platelet count, and transfusion status. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmelli, P.; Lasho, T.L.; Rotunno, G.; Mudireddy, M.; Mannarelli, C.; Nicolosi, M.; Pacilli, A.; Pardanani, A.; Rumi, E.; Rosti, V.; et al. MIPSS70: Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Score System for Transplantation-Age Patients With Primary Myelofibrosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstovsek, S.; Mesa, R.A.; Gotlib, J.; Gupta, V.; DiPersio, J.F.; Catalano, J.V.; Deininger, M.W.; Miller, C.B.; Silver, R.T.; Talpaz, M.; et al. Long-term treatment with ruxolitinib for patients with myelofibrosis: 5-year update from the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 COMFORT-I trial. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrison, C.N.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Kiladjian, J.J.; Al-Ali, H.K.; Gisslinger, H.; Knoops, L.; Cervantes, F.; Jones, M.M.; Sun, K.; McQuitty, M.; et al. Long-term findings from COMFORT-II, a phase 3 study of ruxolitinib vs best available therapy for myelofibrosis. Leukemia 2016, 30, 1701–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kvasnicka, H.M.; Thiele, J.; Bueso-Ramos, C.E.; Sun, W.; Cortes, J.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Verstovsek, S. Long-term effects of ruxolitinib versus best available therapy on bone marrow fibrosis in patients with myelofibrosis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tefferi, A.; Thiele, J.; Orazi, A.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; Barbui, T.; Hanson, C.A.; Barosi, G.; Verstovsek, S.; Birgegard, G.; Mesa, R.; et al. Proposals and rationale for revision of the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis: Recommendations from an ad hoc international expert panel. Blood 2007, 110, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbui, T.; Thiele, J.; Gisslinger, H.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Guglielmelli, P.; Orazi, A.; Tefferi, A. The 2016 WHO classification and diagnostic criteria for myeloproliferative neoplasms: Document summary and in-depth discussion. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tefferi, A.; Cervantes, F.; Mesa, R.; Passamonti, F.; Verstovsek, S.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Gotlib, J.; Dupriez, B.; Pardanani, A.; Harrison, C.; et al. Revised response criteria for myelofibrosis: International Working Group-Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and Treatment (IWG-MRT) and European LeukemiaNet (ELN) consensus report. Blood 2013, 122, 1395–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sale, G.E.; Deeg, H.J.; Porter, B.A. Regression of myelofibrosis and osteosclerosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation assessed by magnetic resonance imaging and histologic grading. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006, 12, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bain, B.J.; Bailey, K. Pitfalls in obtaining and interpreting bone marrow aspirates: To err is human. J. Clin. Pathol. 2011, 64, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slot, S.; van de Donk, N.; Otten, R.H.J.; Boden, B.J.H.; Zijlstra, J.; Raijmakers, P.; Zweegman, S. The value of bone marrow, liver, and spleen imaging in diagnosis, prognostication, and follow-up monitoring of myeloproliferative neoplasms: A systematic review. Cancer Imaging 2021, 21, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozman, C.; Cervantes, F.; Rozman, M.; Mercader, J.M.; Montserrat, E. Magnetic resonance imaging in myelofibrosis and essential thrombocythaemia: Contribution to differential diagnosis. Br. J. Haematol. 1999, 104, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luker, G.D.; Nguyen, H.M.; Hoff, B.A.; Galban, C.J.; Hernando, D.; Chenevert, T.L.; Talpaz, M.; Ross, B.D. A Pilot Study of Quantitative MRI Parametric Response Mapping of Bone Marrow Fat for Treatment Assessment in Myelofibrosis. Tomography 2016, 2, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglin, T.P.; Crocker, J.; Timmins, A.; Chandler, S.; Boughton, B.J. Bone marrow hypervascularity in patients with myelofibrosis identified by infra-red thermography. Clin. Lab. Haematol. 1991, 13, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirrmeister, H.; Bommer, M.; Buck, A.; Reske, S.N. The bone scan in osteomyelosclerosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2001, 16, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.A.; Choi, Y.; Huang, S.C.; Hoh, C.K.; Dahlbom, M.; Schiepers, C.; Satyamurthy, N.; Barrio, J.R.; Phelps, M.E. Evaluation of the skeletal kinetics of fluorine-18-fluoride ion with PET. J. Nucl. Med. 1992, 33, 633–642. [Google Scholar]

- Temmerman, O.P.; Raijmakers, P.G.; Heyligers, I.C.; Comans, E.F.; Lubberink, M.; Teule, G.J.; Lammertsma, A.A. Bone metabolism after total hip revision surgery with impacted grafting: Evaluation using H2 15O and [18F]fluoride PET; a pilot study. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2008, 10, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scherer, A.; Strupp, C.; Wittsack, H.J.; Engelbrecht, V.; Willers, R.; Germing, U.; Gattermann, N.; Haas, R.; Modder, U. [Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for evaluating bone marrow microcirculation in malignant hematological diseases before and after thalidomide therapy]. Radiologe 2002, 42, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courcoutsakis, N.; Spanoudaki, A.; Maris, T.G.; Astrinakis, E.; Spanoudakis, E.; Tsatalas, C.; Prassopoulos, P. Perfusion parameters analysis of the vertebral bone marrow in patients with Ph(1)(-) chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms (Ph(neg) MPN): A dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) study. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 35, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiat, P.; Ferrant, A.; Cogneau, M.; Bol, A.; Michel, C.; Rodhain, J.; Michaux, J.L.; Sokal, G. Assessment of bone marrow blood flow using positron emission tomography: No relationship with bone marrow cellularity. Br. J. Haematol. 1987, 66, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahtinen, R.; Lahtinen, T.; Romppanen, T. Bone and bone-marrow blood flow in chronic granulocytic leukemia and primary myelofibrosis. J. Nucl. Med. 1982, 23, 218–224. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke, D.; Parker, H.; Anger, H.O.; McRae, J.; Dobson, E.L.; Yano, Y.; Naets, J.P.; Linfoot, J. Markedly increased bone blood flow in myelofibrosis. J. Nucl. Med. 1971, 12, 506–512. [Google Scholar]

- Danad, I.; Raijmakers, P.G.; Appelman, Y.E.; Harms, H.J.; de Haan, S.; van den Oever, M.L.; van Kuijk, C.; Allaart, C.P.; Hoekstra, O.S.; Lammertsma, A.A.; et al. Coronary risk factors and myocardial blood flow in patients evaluated for coronary artery disease: A quantitative [15O]H2O PET/CT study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2012, 39, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Emanuel, R.M.; Dueck, A.C.; Geyer, H.L.; Kiladjian, J.J.; Slot, S.; Zweegman, S.; te Boekhorst, P.A.; Commandeur, S.; Schouten, H.C.; Sackmann, F.; et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) symptom assessment form total symptom score: Prospective international assessment of an abbreviated symptom burden scoring system among patients with MPNs. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 4098–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thiele, J.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; Facchetti, F.; Franco, V.; van der Walt, J.; Orazi, A. European consensus on grading bone marrow fibrosis and assessment of cellularity. Haematologica 2005, 90, 1128–1132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kvasnicka, H.M.; Beham-Schmid, C.; Bob, R.; Dirnhofer, S.; Hussein, K.; Kreipe, H.; Kremer, M.; Schmitt-Graeff, A.; Schwarz, S.; Thiele, J.; et al. Problems and pitfalls in grading of bone marrow fibrosis, collagen deposition and osteosclerosis—A consensus-based study. Histopathology 2016, 68, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavini, C.; Kramer, G.; Pieters-den Bos, I.; Hoekstra, O.; Marcus, J.T. MRI protocol optimization for quantitative DCE-MRI of the spine. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2017, 44, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tofts, P.S.; Brix, G.; Buckley, D.L.; Evelhoch, J.L.; Henderson, E.; Knopp, M.V.; Larsson, H.B.; Lee, T.Y.; Mayr, N.A.; Parker, G.J.; et al. Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T(1)-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: Standardized quantities and symbols. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 1999, 10, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavini, C.; Maas, M. DCE-MRI analysis package comprising pixel-by-pixel classification of time intensity curves shapes, permeability maps and Gd concentration calculation. In Proceedings of the ESMRMB, Valencia, Spain, 2–4 October 2008; p. 486, MAGMA. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, G.J.; Roberts, C.; Macdonald, A.; Buonaccorsi, G.A.; Cheung, S.; Buckley, D.L.; Jackson, A.; Watson, Y.; Davies, K.; Jayson, G.C. Experimentally-derived functional form for a population-averaged high-temporal-resolution arterial input function for dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006, 56, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vucht, N.; Santiago, R.; Lottmann, B.; Pressney, I.; Harder, D.; Sheikh, A.; Saifuddin, A. The Dixon technique for MRI of the bone marrow. Skeletal. Radiol. 2019, 48, 1861–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpdogan, O.; Budak-Alpdogan, T.; Bayik, M.; Akoglu, T.; Kodalli, N.; Gurmen, N. Magnetic resonance imaging in myelofibrosis. Blood 1998, 92, 2995–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, W.; Vernon, C.; Muzi, M.; Mankoff, D.A.; Link, J.M.; Conrad, E.U.; Eary, J.F. Comparison of different quantitative approaches to 18F-fluoride PET scans. J. Nucl. Med. 2004, 45, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Fu, J.; Liu, G.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Q.; Wang, S.Y. Angiogenesis in JAK2 V617F positive myeloproliferative neoplasms and ruxolitinib decrease VEGF, HIF-1 enesis in JAK2 V617F positive cells. Leuk. Lymphoma 2018, 59, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhani, A.R.; Hayes, C.; Landau, S.; Leach, M.O. Reproducibility of quantitative dynamic MRI of normal human tissues. NMR Biomed. 2002, 15, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breault, S.R.; Heye, T.; Bashir, M.R.; Dale, B.M.; Merkle, E.M.; Reiner, C.S.; Faridi, K.F.; Gupta, R.T. Quantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of pelvic and lumbar bone marrow: Effect of age and marrow fat content on pharmacokinetic parameter values. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2013, 200, W297–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavini, C. Simulating the effect of input errors on the accuracy of Tofts’ pharmacokinetic model parameters. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015, 33, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosas-Garcia, S.; Moehler, T.; Wasser, K.; Kiessling, F.; Bartl, R.; Zuna, I.; Hillengass, J.; Goldschmidt, H.; Kauczor, H.U.; Delorme, S. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for assessing the disease activity of multiple myeloma: A comparative study with histology and clinical markers. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2005, 22, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merz, M.; Ritsch, J.; Kunz, C.; Wagner, B.; Sauer, S.; Hose, D.; Moehler, T.; Delorme, S.; Goldschmidt, H.; Zechmann, C.; et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for assessment of antiangiogenic treatment effects in multiple myeloma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kahn, D.; Weiner, G.J.; Ben-Haim, S.; Ponto, L.L.; Madsen, M.T.; Bushnell, D.L.; Watkins, G.L.; Argenyi, E.A.; Hichwa, R.D. Positron emission tomographic measurement of bone marrow blood flow to the pelvis and lumbar vertebrae in young normal adults. Blood 1994, 83, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Technique | Regions of Interest a | Outcome Measure(s) |

|---|---|---|

| T1-weighted MRI | Spinal column, pelvis, proximal femora | Visual signal intensity (low/normal/high, homo- or heterogeneous distribution) b |

| Dixon | Th 5/7/9, L1/4, pelvis, proximal femora | Fat–water signal ratio |

| DCE-MRI | Th 7/9, L1 | Ktrans, Ve, Kep |

| 15O-water PET | Th 5/7/9 | Blood flow in ml/min/ml |

| 18F-NaF PET | Th 5/7/9, L1/4, pelvis, proximal femora | Ki, SUVmean, SUVintegral |

| Pt 1 | Pt 2 | Pt 3 | Pt 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | male | female | male | male |

| Age at T0, years | 75 | 64 | 47 | 65 |

| Time since diagnosis, months | 31 | 2 | 30 | 262 |

| Driving mutation | JAK2V617F | JAK2V617F | JAK2V617F | calreticulin |

| Prior treatment | - | - | - | - |

| Comorbidities | - | atrial fibrillation, hypertension | - | - |

| Transfusion history | no | yes (2 months) | no | no |

| DIPSS plus risk score at T0 | int-1 | int-2 | int-1 | int-2 |

| Main reason for treatment | abd. discomfort | night sweats, itching | night sweats, abd. discomfort | night sweats, weight loss |

| Ruxolitinib starting dose, mg/day | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| Dose adjustments (reason) | no | Dose decrease to 5 mg/day (cytopenia) | no | Dose decrease to 20 mg/day (anemia) |

| Grade ≥ 3 adverse events | no | neutropenia | no | anemia |

| Blood transfusions since T0 | no | yes | no | yes |

| Follow-up | deceased | transformation AML | alive | alive |

| Spleen Volume * | MPN-SAF TSS | Bone Marrow Biopsy | IWG-MRT/ELN ^ | DIPSS Plus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellularity | Fibrosis ^ | Fat | MVD | |||||

| Pt 1 | ||||||||

| T0 | 3580 mL | 19 | high | 3 (+) | low | n.e. | - | int-1 |

| T6 | 1970 mL | 22 | low | 2-3 (+) | ↑ | 23/HPF | CI | int-1 |

| T24 | 1600 mL | 23 | n.e. | n.e. (+) | n.e. | n.e. | CI | int-2 |

| Pt 2 | ||||||||

| T0 | 480 mL | unknown | high | 3 (+) | low | 12/HPF | - | int-2 |

| Pt 3 | ||||||||

| T0 | 2920 mL | 14 | high | 3 (+) | low | 22/HPF | - | int-1 |

| T6 | 2140 mL | 14 | normal | 3 (+) | ↑ | 33/HPF | SD | int-1 |

| T18 | 1780 mL | 28 | high | 3 (+) | Low (↓) | 32/HPF | CI | int-1 |

| Pt 4 | ||||||||

| T0 | 2490 mL | 46 | low | 3 (+) | low | 33/HPF | - | int-2 |

| T6 | 1830 mL | 26 | low | 3 (+) | ↑ | 26/HPF | SD | int-2 |

| T18 | 1520 mL | 22 | n.e. | n.e. (+) | n.e. | n.e. | SD | int-2 |

| MRI T1 a | Dixon Fat–Water Signal Ratio b | DCE-MRI c (Spine) | 15O-Water PET Flow d (Spine) | 18F-NaF PET SUVintegral e | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pelvis | Spine | Pelvis | Spine | Ve | Ktrans | Pelvis | Spine | ||

| Pt 1 | |||||||||

| T0 | 1-2P | 1P | 0.69 (–) | 0.26 (–) | - | - | 0.33 (–) | 0.08 (–) | 0.08 (–) |

| T6 | 2P | 1P | 1.48 (+114%) | 0.32 (+23%) | +54% | −38% | 0.17 (−48%) | 0.05 (−37%) | 0.08 (=) |

| T24 | 2P | 1-2P | 3.37 (+388%) | 1.32 (+407%) | +90% | −30% | 0.23 (−30%) | 0.05 (−37%) | 0.07 (−12%) |

| Pt 2 | |||||||||

| T0 | 1H | 1H | 0.43 (–) | 0.26 (–) | - | - | 0.40 (–) | 0.12 (–) | 0.11 (–) |

| Pt 3 | |||||||||

| T0 | 1P | 1H | 0.5 (–) | 0.22 (–) | - | - | 0.37 (–) | 0.11 (–) | 0.09 (–) |

| T6 | 2P | 1P | 1.14 (+128%) | 0.28 (+27%) | +11% | +1% | 0.45 (+22%) | 0.12 (+9%) | 0.09 (=) |

| T18 | 2P | 1P | 1.12 (+124%) | 0.16 −27%) | −1% | −13% | 0.54 (+46%) | - | 0.08 (−11%) |

| Pt 4 | |||||||||

| T0 | 1H | 0H | 0.77 (–) | 0.34 (–) | - | - | 0.61 (–) | 0.14 (–) | 0.22 (–) |

| T6 | 1H | 0H | 1.44 (+87%) | 0.76 (+124%) | +33% | +34% | 0.63 (+3%) | 0.17 (+21%) | 0.23 (+5%) |

| T18 | 1H | 0H | 1.34 (+74%) | 0.48 (+41%) | +153% | +185% | 0.66 (+8%) | 0.13 (−7%) | 0.20 (−11%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Slot, S.; Lavini, C.; Zwezerijnen, G.J.C.; Boden, B.J.H.; Marcus, J.T.; Huisman, M.C.; Yaqub, M.; Barbé, E.; Wondergem, M.J.; Zijlstra, J.M.; et al. Characterizing the Bone Marrow Environment in Advanced-Stage Myelofibrosis during Ruxolitinib Treatment Using PET/CT and MRI: A Pilot Study. Tomography 2023, 9, 459-474. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography9020038

Slot S, Lavini C, Zwezerijnen GJC, Boden BJH, Marcus JT, Huisman MC, Yaqub M, Barbé E, Wondergem MJ, Zijlstra JM, et al. Characterizing the Bone Marrow Environment in Advanced-Stage Myelofibrosis during Ruxolitinib Treatment Using PET/CT and MRI: A Pilot Study. Tomography. 2023; 9(2):459-474. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography9020038

Chicago/Turabian StyleSlot, Stefanie, Cristina Lavini, Gerben J. C. Zwezerijnen, Bouke J. H. Boden, J. Tim Marcus, Marc C. Huisman, Maqsood Yaqub, Ellis Barbé, Mariëlle J. Wondergem, Josée M. Zijlstra, and et al. 2023. "Characterizing the Bone Marrow Environment in Advanced-Stage Myelofibrosis during Ruxolitinib Treatment Using PET/CT and MRI: A Pilot Study" Tomography 9, no. 2: 459-474. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography9020038

APA StyleSlot, S., Lavini, C., Zwezerijnen, G. J. C., Boden, B. J. H., Marcus, J. T., Huisman, M. C., Yaqub, M., Barbé, E., Wondergem, M. J., Zijlstra, J. M., Zweegman, S., & Raijmakers, P. G. (2023). Characterizing the Bone Marrow Environment in Advanced-Stage Myelofibrosis during Ruxolitinib Treatment Using PET/CT and MRI: A Pilot Study. Tomography, 9(2), 459-474. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography9020038