Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Forearm in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Assessments

2.2. MRI Acquisition

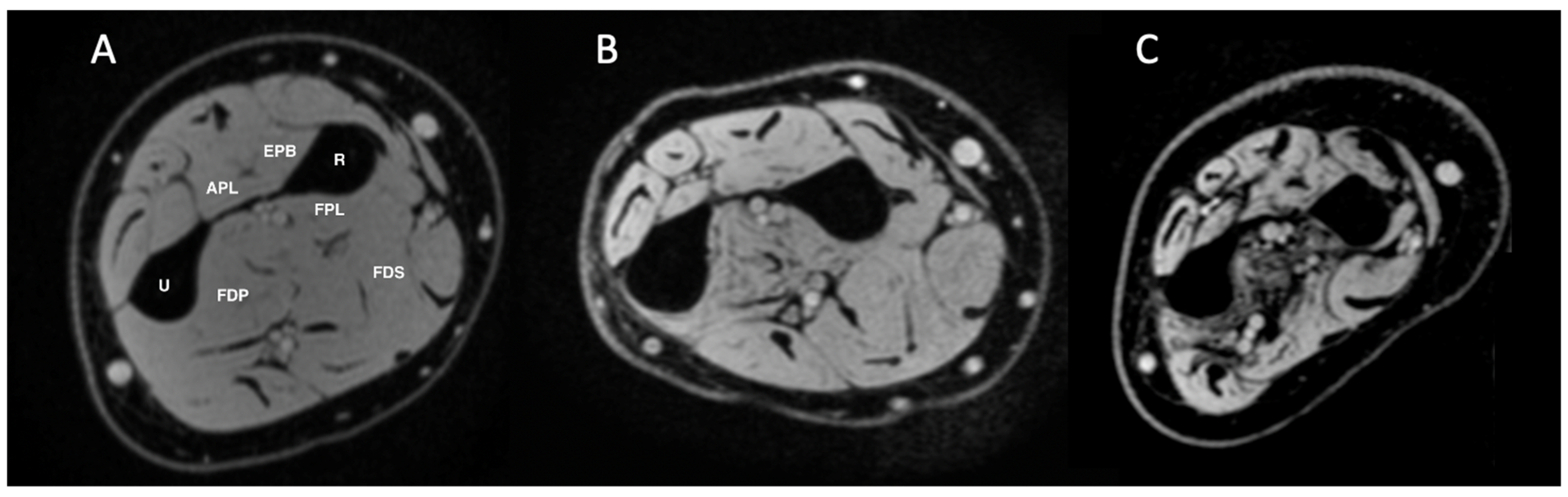

2.3. MRI Image Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Clinical Assessments

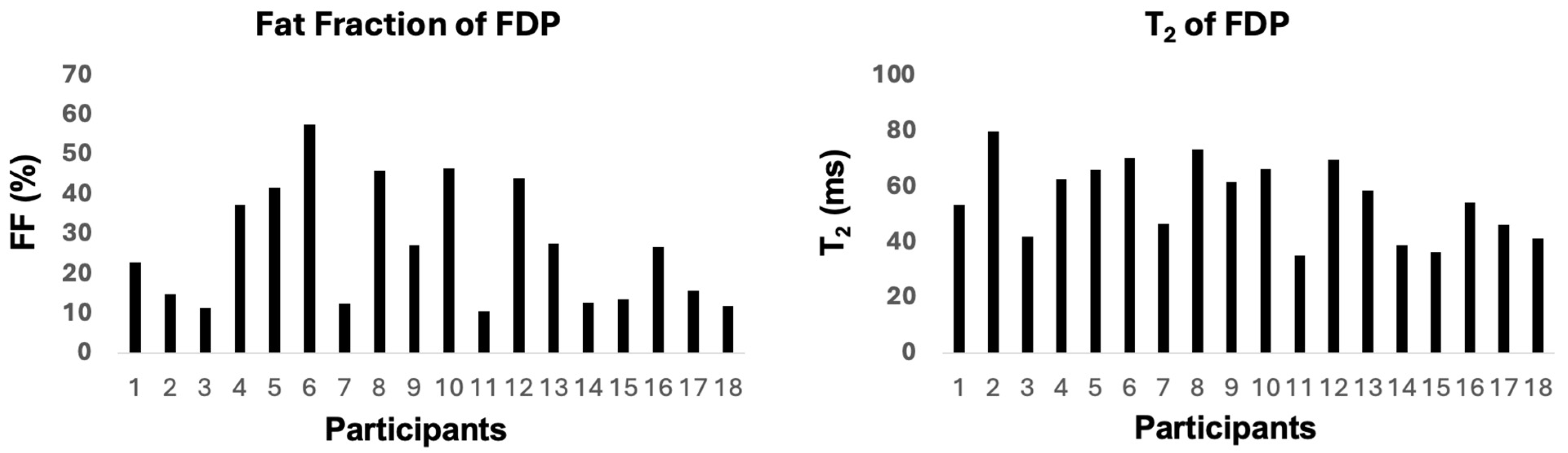

3.2. MRI Findings

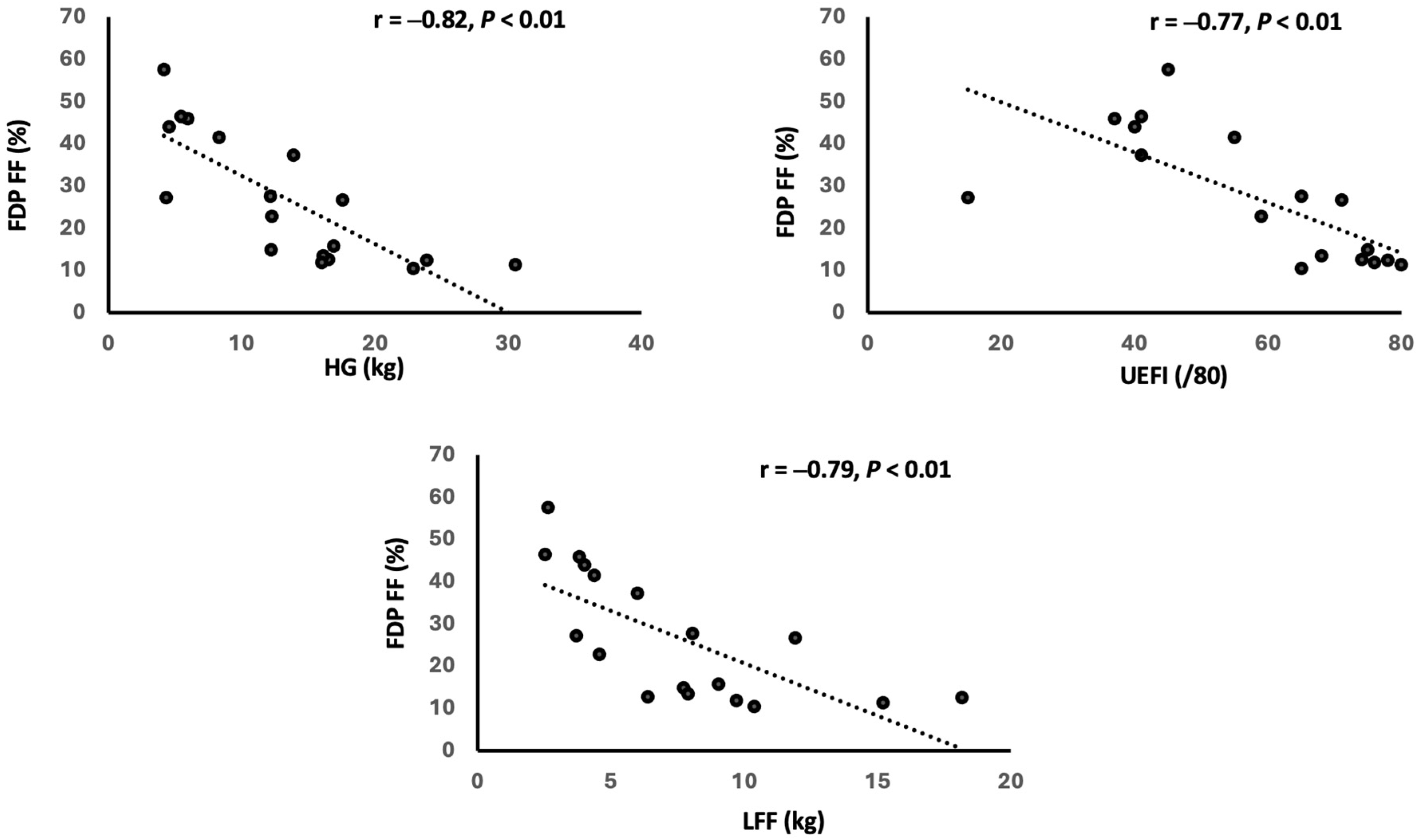

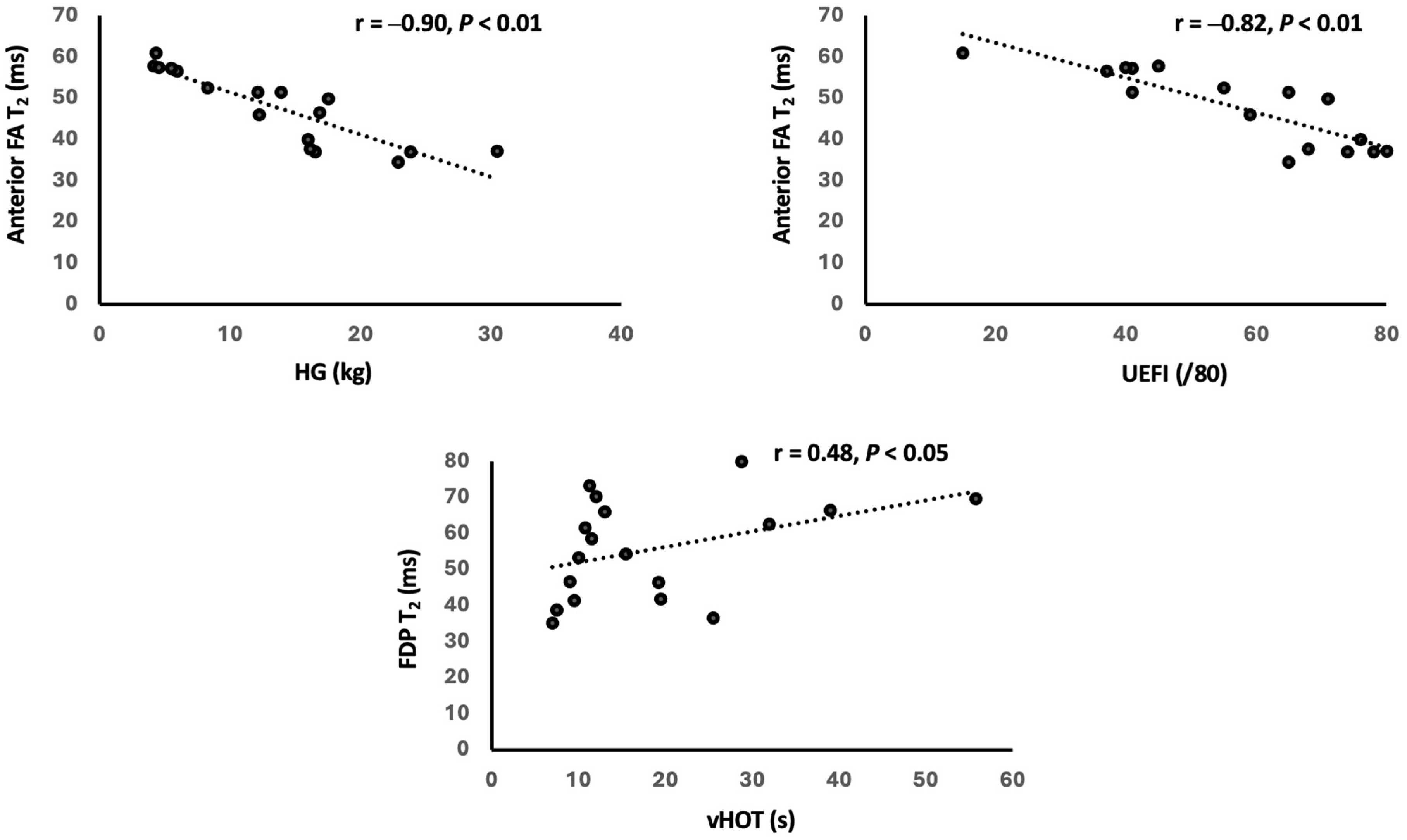

3.3. Relationship Between MRI and Clinical Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Increased FF and T2 Values in DM1 Forearm

4.2. Contribution of FF and T2 to Strength and Function Impairments

4.3. Correlation of CTG Size with FF and T2 Values

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DM1 | Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 |

| ADLs | Activities of Daily Living |

| qMRI | Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| FF | Fat Fraction |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| QMT | Quantitative Muscle Testing |

| vHOT | Video Hand Opening Time |

| UEFI | Upper Extremity Function Index |

| LFF | Long Finger fFexor |

| HG | Handgrip |

| FDP | Flexor Digitorum Profundus |

| FDS | Flexor Digitorum Superficialis |

| FPL | Flexor Pollicis Longus |

| EPB | Extensor Pollicis Brevis |

| APL | Abductor Pollicis Longus |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

References

- Bird, T.D. Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Bick, S., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meola, G.; Cardani, R. Myotonic dystrophies: An update on clinical aspects, genetic, pathology, and molecular pathomechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, S.; Gourdon, G. DM1 Phenotype Variability and Triplet Repeat Instability: Challenges in the Development of New Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogrel, J.Y.; Ollivier, G.; Ledoux, I.; Hébert, L.J.; Eymard, B.; Puymirat, J.; Bassez, G. Relationships between grip strength, myotonia, and CTG expansion in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2017, 4, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugie, K.; Sugie, M.; Taoka, T.; Tonomura, Y.; Kumazawa, A.; Izumi, T.; Kichikawa, K.; Ueno, S. Characteristic MRI Findings of upper Limb Muscle Involvement in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Hamano, T.; Kawamura, Y.; Kimura, H.; Matsunaga, A.; Ikawa, M.; Yamamura, O.; Mutoh, T.; Higuchi, I.; Kuriyama, M.; et al. Muscle MRI of the Upper Extremity in the Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1. Eur. Neurol. 2016, 76, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heskamp, L.; van Nimwegen, M.; Ploegmakers, M.J.; Bassez, G.; Deux, J.-F.; Cumming, S.A.; Monckton, D.G.; van Engelen, B.G.M.; Heerschap, A. Lower extremity muscle pathology in myotonic dystrophy type 1 assessed by quantitative MRI. Neurology 2019, 92, e2803–e2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiba, B.; Richard, N.; Hébert, L.J.; Coté, C.; Nejjari, M.; Vial, C.; Bouhour, F.; Puymirat, J.; Janier, M. Quantitative assessment of skeletal muscle degeneration in patients with myotonic dystrophy type 1 using MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 35, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenninger, S.; Montagnese, F.; Schoser, B. Core Clinical Phenotypes in Myotonic Dystrophies. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerman, K.A.; Howe, S.J.; Heatwole, C.R.; Christopher Project Reference Group. The myotonic dystrophy experience: A North American cross-sectional study. Muscle Nerve 2019, 59, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heatwole, C.; Bode, R.; Johnson, N.; Quinn, C.; Martens, W.; McDermott, M.P.; Rothrock, N.; Thornton, C.; Vickrey, B.; Victorson, D.; et al. Patient-reported impact of symptoms in myotonic dystrophy type 1 (PRISM-1). Neurology 2012, 79, 348–357, Correction in Neurology 2012, 79, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakiewicz, J.; Sinclair, C.D.J.; Fischer, D.; Walter, G.A.; Kan, H.E.; Hollingsworth, K.G. Quantifying fat replacement of muscle by quantitative MRI in muscular dystrophy. J. Neurol. 2017, 264, 2053–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.H.; Kim, H.K.; Merrow, A.C.; Laor, T.; Serai, S.; Horn, P.S.; Kim, D.H.; Wong, B.L. Quantitative Skeletal Muscle MRI: Part 1, Derived T2 Fat Map in Differentiation Between Boys with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and Healthy Boys. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015, 205, W207–W215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wokke, B.H.; Van Den Bergen, J.C.; Hooijmans, M.T.; Verschuuren, J.J.; Niks, E.H.; Kan, H.E. T2 relaxation times are increased in Skeletal muscle of DMD but not BMD patients. Muscle Nerve 2016, 53, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Plas, E.; Gutmann, L.; Thedens, D.; Shields, R.K.; Langbehn, K.; Guo, Z.; Sonka, M.; Nopoulos, P. Quantitative muscle MRI as a sensitive marker of early muscle pathology in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Muscle Nerve 2021, 63, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heskamp, L.; Okkersen, K.; van Nimwegen, M.; Ploegmakers, M.J.; Bassez, G.; Deux, J.-F.; van Engelen, B.G.; Heerschap, A. Quantitative Muscle MRI Depicts Increased Muscle Mass after a Behavioral Change in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1. Radiology 2020, 297, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichinger, K.; Dilek, N.; Dekdebrun, J.; Martens, W.; Heatwole, C.; Thornton, C.; Moxley, R.; Pandya, S.P. 18.3 Test–retest reliability of strength measurements of the long finger flexors (LFF) in patients with myotonic dystrophy type 1. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2017, 23, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatwole, C.; Bode, R.; Johnson, N.E.; Dekdebrun, J.; Dilek, N.; Eichinger, K.; Hilbert, J.E.; Logigian, E.; Luebbe, E.; Martens, W.; et al. Myotonic dystrophy health index: Correlations with clinical tests and patient function. Muscle Nerve 2016, 53, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichinger, K.; Currence, M.; Capron, K.; Duong, T.; Gee, R.; Herbelin, L.; Joe, G.; King, W.; Lott, D. Muscle Strength and Function Measures in a Multicenter Study of Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 (DM1): Baseline Impairment and Test-Retest Agreement over 3 Months. Neurology 2018, 90 (Suppl. S15), P5.455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puwanant, A.; Statland, J.; Dilek, N.; Moxley, R.; Thornton, C. Video hand opening time (vHOT) in myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) (P05.188). Neurology 2012, 78 (Suppl. S1), P05.188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, J.; Creigh, P.D.; Dekdebrun, J.; Eichinger, K.; Thornton, C.A. Remote assessment of myotonic dystrophy type 1: A feasibility study. Muscle Nerve 2022, 66, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bos, I.; Wynia, K.; Drost, G.; Almansa, J.; Kuks, J.B.M. The extremity function index (EFI), a disability severity measure for neuromuscular diseases: Psychometric evaluation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 1561–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roussel, M.P.; Fiset, M.M.; Gauthier, L.; Lavoie, C.; McNicoll, É.; Pouliot, L.; Gagnon, C.; Duchesne, E. Assessment of muscular strength and functional capacity in the juvenile and adult myotonic dystrophy type 1 population: A 3-year follow-up study. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 4221–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiowetz, V.; Kashman, N.; Volland, G.; Weber, K.; Dowe, M.; Rogers, S. Grip and pinch strength: Normative data for adults. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1985, 66, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arpan, I.; Willcocks, R.J.; Forbes, S.C.; Finkel, R.S.; Lott, D.J.; Rooney, W.D.; Triplett, W.T.; Senesac, C.R.; Daniels, M.J.; Byrne, B.J.; et al. Examination of effects of corticosteroids on skeletal muscles of boys with DMD using MRI and MRS. Neurology 2014, 83, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischmann, A.; Hafner, P.; Fasler, S.; Gloor, M.; Bieri, O.; Studler, U.; Fischer, D. Quantitative MRI can detect subclinical disease progression in muscular dystrophy. J. Neurol. 2012, 259, 1648–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplett, W.T.; Baligand, C.; Forbes, S.C.; Willcocks, R.J.; Lott, D.J.; DeVos, S.; Pollaro, J.; Rooney, W.D.; Sweeney, H.L.; Bönnemann, C.G.; et al. Chemical shift-based MRI to measure fat fractions in dystrophic skeletal muscle. Magn. Reson. Med. 2014, 72, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpan, I.; Forbes, S.C.; Lott, D.J.; Senesac, C.R.; Daniels, M.J.; Triplett, W.T.; Deol, J.K.; Sweeney, H.L.; Walter, G.A.; Vandenborne, K. T2 mapping provides multiple approaches for the characterization of muscle involvement in neuromuscular diseases: A cross-sectional study of lower leg muscles in 5–15-year-old boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. NMR Biomed. 2013, 26, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, P.; Romu, T.; Brorson, H.; Dahlqvist Leinhard, O.; Månsson, S. Fat quantification in skeletal muscle using multigradient-echo imaging: Comparison of fat and water references. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2016, 43, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamori, M.; Akiyama, S.; Ogata, H.; Yokoi-Hayakawa, M.; Imaizumi-Ohashi, Y.; Seo, Y.; Mizushima, T. Detection of muscle activity with forearm pronation exercise using T2-map MRI. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2020, 32, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dion, E.; Cherin, P.; Payan, C.; Fournet, J.-C.; Papo, T.; Maisonobe, T.; Auberton, E.; Chosidow, O.; Godeau, P.; Piette, J.-C.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging criteria for distinguishing between inclusion body myositis and polymyositis. J. Rheumatol. 2002, 29, 1897–1906. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, T.A.; Hollingsworth, K.G.; Coombs, A.; Sveen, M.-L.; Andersen, S.; Stojkovic, T.; Eagle, M.; Mayhew, A.; De Sousa, P.L.; Dewar, L.; et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2I: A multinational cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, L.A.M.; van der Pol, W.; Schlaffke, L.; Wijngaarde, C.A.; Stam, M.; Wadman, R.I.; Cuppen, I.; van Eijk, R.P.; Asselman, F.; Bartels, B.; et al. Quantitative MRI of skeletal muscle in a cross-sectional cohort of patients with spinal muscular atrophy types 2 and 3. NMR Biomed. 2020, 33, e4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, A.; Lott, D.J.; Willcocks, R.; Forbes, S.C.; Triplett, W.; Dastgir, J.; Yun, P.; Foley, A.R.; Bönnemann, C.G.; Vandenborne, K.; et al. Lower Extremity Muscle Involvement in the Intermediate and Bethlem Myopathy Forms of COL6-Related Dystrophy and Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2020, 7, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mul, K.; Vincenten, S.C.C.; Voermans, N.C.; Lemmers, R.J.; van der Vliet, P.J.; van der Maarel, S.M.; Padberg, G.W.; Horlings, C.G.; van Engelen, B.G. Adding quantitative muscle MRI to the FSHD clinical trial toolbox. Neurology 2017, 89, 2057–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, W.D.; Berlow, Y.A.; Triplett, W.T.; Forbes, S.C.; Willcocks, R.J.; Wang, D.-J.; Arpan, I.; Arora, H.; Senesac, C.; Lott, D.J.; et al. Modeling disease trajectory in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2020, 94, e1622–e1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, A.M.; Willcocks, R.J.; Triplett, W.T.; Forbes, S.C.; Daniels, M.J.; Chakraborty, S.; Lott, D.J.; Senesac, C.R.; Finanger, E.L.; Harrington, A.T.; et al. MR biomarkers predict clinical function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2020, 94, e897–e909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercuri, E.; Talim, B.; Moghadaszadeh, B.; Petit, N.; Brockington, M.; Counsell, S.; Guicheney, P.; Muntoni, F.; Merlini, L. Clinical and imaging findings in six cases of congenital muscular dystrophy with rigid spine syndrome linked to chromosome 1p (RSMD1). Neuromuscul. Disord. 2002, 12, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, D.; Kley, R.A.; Strach, K.; Meyer, C.; Sommer, T.; Eger, K.; Rolfs, A.; Meyer, W.; Pou, A.; Pradas, J.; et al. Distinct muscle imaging patterns in myofibrillar myopathies. Neurology 2008, 71, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barohn, R.J.; Dimachkie, M.M.; Jackson, C.E. A pattern recognition approach to patients with a suspected myopathy. Neurol. Clin. 2014, 32, 569–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, S.; Liewluck, T.; Milone, M. Myopathies with finger flexor weakness: Not only inclusion-body myositis. Muscle Nerve 2020, 62, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldehag, A.S.; Jonsson, H.; Ansved, T. Effects of a hand training programme in five patients with myotonic dystrophy type 1. Occup. Ther. Int. 2005, 12, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldehag, A.; Jonsson, H.; Lindblad, J.; Kottorp, A.; Ansved, T.; Kierkegaard, M. Effects of hand-training in persons with myotonic dystrophy type 1—A randomised controlled cross-over pilot study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 1798–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Subject | Sex | Age (Years) | Age of Diagnosis (Years) | Age of Symptom Onset (Years) | BMI (kg/m2) | CTG Repeat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 25.7 | 18.0 | 12.5 | 29.2 | 553 |

| 2 | M | 51.7 | 40.0 | 37.0 | 21.5 | 153 |

| 3 | M | 22.7 | 17.0 | 12.0 | 21.9 | 270 |

| 4 | F | 42.3 | 37.0 | 29.0 | 26.7 | 443 |

| 5 | F | 35.1 | 32.0 | 23.0 | 22.5 | 590 |

| 6 | M | 31.2 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 30.2 | n.a. |

| 7 | F | 26.2 | 19.0 | 18.0 | 20.5 | 393 |

| 8 | M | 42.9 | 37.0 | 20.0 | 29.5 | n.a. |

| 9 | F | 47.4 | 36.0 | 25.0 | 21.5 | 740 |

| 10 | F | 35.1 | 18.0 | 13.0 | 18.9 | 1033 |

| 11 | F | 21.1 | 19.0 | 15.5 | 22.7 | 513 |

| 12 | M | 48.2 | 32.0 | 29.0 | 24.5 | 134 |

| 13 | F | 55.9 | 25.0 | 40.0 | 26.7 | 973 |

| 14 | F | 18.7 | 10.0 | 12.5 | 18.1 | 440 |

| 15 | F | 54.4 | n.a. | 34.0 | 25.7 | 111 |

| 16 | F | 26.5 | 15.0 | 11.5 | 34.1 | n.a. |

| 17 | M | 42.5 | 11.0 | 9.0 | 18.6 | 953 |

| 18 | F | 23.3 | 22.0 | 17.0 | 31.8 | 440 |

| Mean | 36.2 | 23.8 | 20.8 | 24.7 | 515.9 | |

| SD | 12.3 | 9.8 | 9.5 | 4.8 | 299.8 |

| Subject | HG (kg) | HG Pred (%) | LFF (kg) | UEFI (/80) | vHOT (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12.3 | 22.3 | 4.6 | 59 | 10.0 |

| 2 | 12.2 | 23.7 | 7.7 | 75 | 28.8 |

| 3 | 30.5 | 55.5 | 15.2 | 80 | 19.5 |

| 4 | 13.9 | 43.4 | 6.0 | 41 | 32.0 |

| 5 | 8.3 | 24.6 | 4.4 | 55 | 13.0 |

| 6 | 4.2 | 7.5 | 2.6 | 45 | 12.0 |

| 7 | 23.9 | 70.3 | 18.2 | 78 | 9.0 |

| 8 | 6.0 | 11.2 | 3.8 | 37 | 11.3 |

| 9 | 4.3 | 15.3 | 3.7 | 15 | 10.8 |

| 10 | 5.5 | 16.3 | 2.5 | 41 | 39.0 |

| 11 | 22.9 | 71.5 | 10.4 | 65 | 7.0 |

| 12 | 4.6 | 9.1 | 4.0 | 40 | 55.8 |

| 13 | 12.1 | 46.6 | 8.1 | 65 | 11.5 |

| 14 | 16.5 | 51.7 | 6.4 | 74 | 7.5 |

| 15 | 16.1 | 53.9 | 7.9 | 68 | 25.5 |

| 16 | 17.6 | 51.8 | 11.9 | 71 | 15.5 |

| 17 | 16.9 | 31.8 | 9.0 | n.a. | 19.3 |

| 18 | 16.0 | 50.0 | 9.7 | 76 | 9.5 |

| Mean | 13.5 | 36.5 | 7.6 | 57.9 | 18.7 |

| SD | 7.4 | 20.9 | 4.3 | 18.5 | 13.0 |

| Muscle FF (%) | FDP | FDS | FPL | EPB | APL | Ant. | Post. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | |||||||

| 1 | 22.8 | 13.1 | 20.6 | 11.3 | 12.1 | 19.4 | 21.0 |

| 2 | 14.9 | 10.7 | 12.2 | 9.7 | 8.7 | 15.4 | 13.5 |

| 3 | 11.4 | 10.1 | 12.4 | 12.7 | 14.5 | 12.8 | 14.8 |

| 4 | 37.3 | 18.0 | 21.8 | 37.7 | 43.0 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 5 | 41.6 | 12.5 | 44.1 | 23.2 | 16.9 | 31.9 | 23.1 |

| 6 | 57.6 | 16.1 | 18.2 | 19.3 | 18.8 | 34.6 | 32.4 |

| 7 | 12.5 | n.a. | 19.1 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 8 | 45.9 | 16.5 | 20.5 | 14.6 | 15.3 | 31.3 | 23.8 |

| 9 | 27.3 | 18.5 | 32.9 | 14.2 | 17.7 | 31.3 | 20.9 |

| 10 | 46.5 | 14.9 | 20.7 | 11.8 | 13.3 | 28.0 | 18.6 |

| 11 | 10.5 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 13.5 | 11.4 | 13.3 | 13.9 |

| 12 | 44.0 | 27.6 | 45.7 | n.a. | 43.9 | 31.2 | 32.1 |

| 13 | 27.7 | 17.1 | 19.8 | 15.0 | 18.1 | 25.6 | 20.6 |

| 14 | 12.7 | 14.0 | 13.8 | n.a. | 11.3 | 15.6 | 15.5 |

| 15 | 13.5 | 12.8 | 14.9 | 12.0 | 11.7 | 16.9 | 17.5 |

| 16 | 26.8 | 15.2 | 30.9 | n.a. | 21.0 | 25.4 | 26.0 |

| 17 | 15.7 | 14.7 | 21.8 | 16.6 | 14.3 | 21.0 | 20.3 |

| 18 | 11.8 | 13.2 | 15.9 | 15.1 | 15.5 | 16.2 | 17.4 |

| Mean | 26.7 | 15.1 | 22.1 | 16.2 | 18.1 | 23.1 | 20.7 |

| SD | 15.2 | 4.0 | 10.0 | 7.1 | 10.1 | 7.6 | 5.8 |

| Muscle T2 (ms) | FDP | FDS | FPL | EPB | APL | Ant. | Post. | Avg. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | ||||||||

| 1 | 53.3 | 44.6 | 44.4 | 42.5 | 44.1 | 45.9 | 41.2 | 43.6 |

| 2 | 79.8 | 69.4 | 54.9 | 42.1 | 38.5 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 3 | 41.8 | 34.2 | 38.2 | 33.8 | 32.3 | 37.2 | 32.7 | 34.9 |

| 4 | 62.4 | 55.6 | 45.3 | 44.1 | 40.5 | 51.4 | 39.9 | 45.6 |

| 5 | 65.9 | 52.2 | 57.9 | 52.4 | 42.8 | 52.5 | 44.2 | 48.3 |

| 6 | 70.1 | 59.0 | 69.3 | 56.5 | 48.3 | 57.8 | 50.4 | 54.1 |

| 7 | 46.6 | 34.8 | 40.2 | 33.6 | 34.6 | 37.0 | 32.3 | 34.6 |

| 8 | 73.2 | 56.6 | 61.3 | 43.3 | 42.9 | 56.5 | 47.6 | 52.1 |

| 9 | 61.5 | 63.6 | 68.1 | 39.3 | 44.6 | 60.9 | 45.5 | 53.2 |

| 10 | 66.3 | 55.4 | 56.4 | 46.1 | 44.5 | 57.1 | 44.7 | 50.9 |

| 11 | 35.0 | 31.8 | 35.4 | 34.4 | 36.3 | 34.5 | 33.6 | 34.1 |

| 12 | 69.5 | 53.7 | 66.7 | n.a. | 60.6 | 57.5 | 55.6 | 56.5 |

| 13 | 58.5 | 45.2 | 44.1 | 43.0 | 43.7 | 51.4 | 42.9 | 47.2 |

| 14 | 38.7 | 33.7 | 38.1 | n.a. | 35.3 | 36.9 | 34.3 | 35.6 |

| 15 | 36.5 | 35.1 | 33.7 | 33.0 | 33.1 | 37.6 | 34.6 | 36.1 |

| 16 | 54.1 | 43.3 | 60.5 | n.a. | 50.0 | 49.9 | 42.3 | 46.1 |

| 17 | 46.3 | 37.8 | 46.3 | 37.1 | 39.6 | 46.5 | 40.0 | 43.2 |

| 18 | 41.3 | 35.7 | 36.6 | 35.0 | 38.3 | 40.0 | 35.9 | 38.0 |

| Mean | 55.6 | 46.7 | 49.9 | 41.1 | 41.7 | 47.7 | 41.0 | 44.4 |

| SD | 13.8 | 11.7 | 12.1 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 8.9 | 6.6 | 7.6 |

| FDP | FPL | FDS | APL | EPB | Ant. FA | Post. FA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HG | −0.82 ** | −0.45 | −0.61 ** | −0.41 | −0.17 | −0.82 ** | −0.60 * |

| HG pred | −0.82 ** | −0.48 * | −0.59 * | −0.36 | −0.10 | −0.77 ** | −0.65 ** |

| LFF | −0.79 ** | −0.41 | −0.55 * | −0.22 | −0.09 | −0.74 ** | −0.46 |

| UEFI | −0.77 ** | −0.68 ** | −0.78 ** | −0.49 | −0.36 | −0.81 ** | −0.63 * |

| vHOT | 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.28 | −0.03 | 0.18 | 0.16 |

| FDP | FPL | FDS | APL | EPB | Ant. FA | Post. FA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HG | −0.75 ** | −0.73 ** | −0.83 ** | −0.72 ** | −0.80 ** | −0.90 ** | −0.90 ** |

| HG pred | −0.81 ** | −0.82 ** | −0.84 ** | −0.74 ** | −0.75 ** | −0.89 ** | −0.92 ** |

| LFF | −0.66 ** | −0.66 ** | −0.73 ** | −0.62 ** | −0.79 ** | −0.80 ** | −0.81 ** |

| UEFI | −0.55 * | −0.69 ** | −0.64 ** | −0.68 ** | −0.67 ** | −0.82 ** | −0.83 ** |

| vHOT | 0.48 * | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eierle, S.; Taivassalo, T.; Park, H.; Cooke, K.D.; Moslemi, Z.; Forbes, S.C.; Walter, G.A.; Vandenborne, K.; Subramony, S.H.; Lott, D.J. Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Forearm in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1. Tomography 2025, 11, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography11120136

Eierle S, Taivassalo T, Park H, Cooke KD, Moslemi Z, Forbes SC, Walter GA, Vandenborne K, Subramony SH, Lott DJ. Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Forearm in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1. Tomography. 2025; 11(12):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography11120136

Chicago/Turabian StyleEierle, Sydney, Tanja Taivassalo, Hyunjun Park, Korey D. Cooke, Zahra Moslemi, Sean C. Forbes, Glenn A. Walter, Krista Vandenborne, S. H. Subramony, and Donovan J. Lott. 2025. "Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Forearm in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1" Tomography 11, no. 12: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography11120136

APA StyleEierle, S., Taivassalo, T., Park, H., Cooke, K. D., Moslemi, Z., Forbes, S. C., Walter, G. A., Vandenborne, K., Subramony, S. H., & Lott, D. J. (2025). Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Forearm in Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1. Tomography, 11(12), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography11120136