1. Introduction

Automated deep learning-based volumetric (3D) medical image segmentation based on a small number of expert-annotated ground truth datasets is increasingly being used and has enabled semantic segmentation in large datasets, which would otherwise have required extensive, time-consuming manual labor [

1,

2]. However, validating the resulting automated segmentations, especially in large-scale datasets such as cohort studies, remains challenging. Large publicly available annotated datasets exist for certain tasks, such as CT-based lung segmentation, and can aid in external validation [

3,

4,

5]. But these datasets are frequently not available for specialized segmentation tasks, imaging modalities such as certain MRI sequences or pathologies of interest. On the other hand, MRI is now increasingly being used in large population-based cohort studies around the world [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Semantic segmentation plays a key role in answering imaging-based research questions in these cases. However, visual quality control of every automated segmentation may not be feasible in large-scale cohort studies, and quality control of select cases cannot rule out the falsification of subsequent analyses by erroneous segmentations. Only few studies reported on the use of visual quality control in large cohort studies [

2,

10,

11]. Various algorithmic approaches have been published in recent years to address this issue, for example, by quantifying uncertainty within a segmentation algorithm or an ensemble of segmentation algorithms [

12,

13]. While these may help identify potentially erroneous segmentations and provide an indication of overall segmentation performance, significant segmentation errors may still be missed. Visual quality control on a case-by-case basis, therefore, remains desirable. Few previous publications presented and evaluated dedicated software tools that streamline the process of loading imaging data and associated segmentation masks for manual slice-based 3D quality control [

2,

14,

15]. However, evaluation of numerous slices per case still accumulates to a significant amount of time in large-scale studies like the German National Cohort (NAKO) with ~30,000 participants undergoing MRI scans or the UK Biobank imaging study which includes imaging of ~100,000 participants [

6,

7]. Two-dimensional projection images for visualization and analysis of three-dimensional imaging data, especially maximum intensity projections, are routinely used for visualization and aid assessment of computed tomography and MRI examinations, especially angiographic examinations [

16,

17]. Standard deviation projection images have been previously reported to improve visualization and outlining of cells on microscopy images [

18]. To our knowledge, only one prior study reported on the use of projection images for visual quality control of automated segmentations; however, the accuracy of the method compared to slice-based review was not reported [

2]. We, therefore, assessed the diagnostic accuracy of different 2D projection images of 3D right and left lung segmentation masks based on MRI examinations of a large-scale cohort study for rapid identification of segmentation errors compared with slice-based review.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

The lung segmentation algorithm was trained on MRI data of two national multicenter studies: the imaging-based sub-study of the COSYCONET cohort study on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (“COPD and SYstemic consequences-COmorbidities NETwork,” NCT01245933; “Image-based structural and functional phenotyping of the COSYCONET cohort using MRI and CT (MR-COPD),” NCT02629432) and the population-based NAKO [

19,

20,

21]. The present analysis was solely performed on lung segmentations of NAKO. NAKO is an ongoing population-based study within a network of 25 institutions at 18 regional examination sites. The main objective is the investigation of risk factors for chronic diseases. The baseline assessment enrolled 205,415 participants from the general population (age 19–74 years) between 2014 and 2019, of which 30,861 also participated in the NAKO MRI study. This imaging sub-study was carried out at five imaging centers. For the present analysis, automated lung segmentation was performed on MRI data of 11,190 participants available at the time of the investigation, enrolled until 31 December 2016. Segmentation visualization, as assessed in the present manuscript, was evaluated in 300 of these participants, which were selected based on model uncertainty from the neural network ensemble used for automatic segmentation. Uncertainty was quantified based on the volumetric disagreement among model outputs:

for binary segmentation

y on image

x, Dice overlap of pairwise segmentation masks

Dice(i, j) generated across all ensemble models, and the number of mask combinations

k. Three subsets of 100 cases were then selected, representing the highest, lowest and median uncertainty measurements. The selection was aimed at representing (1) cases with a high prevalence of salient errors, (2) cases with a low prevalence of subtle errors, and (3) the most frequent cases within the underlying dataset. The selection was not intended to represent the dataset as a whole. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The present analysis was approved by the NAKO Use and Access Committee and the steering committee of the COSYCONET study. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of XXXX (S-193/2021).

2.2. MR Imaging

Whole-body MRI scans as part of NAKO were conducted at five study centers and are described in detail elsewhere [

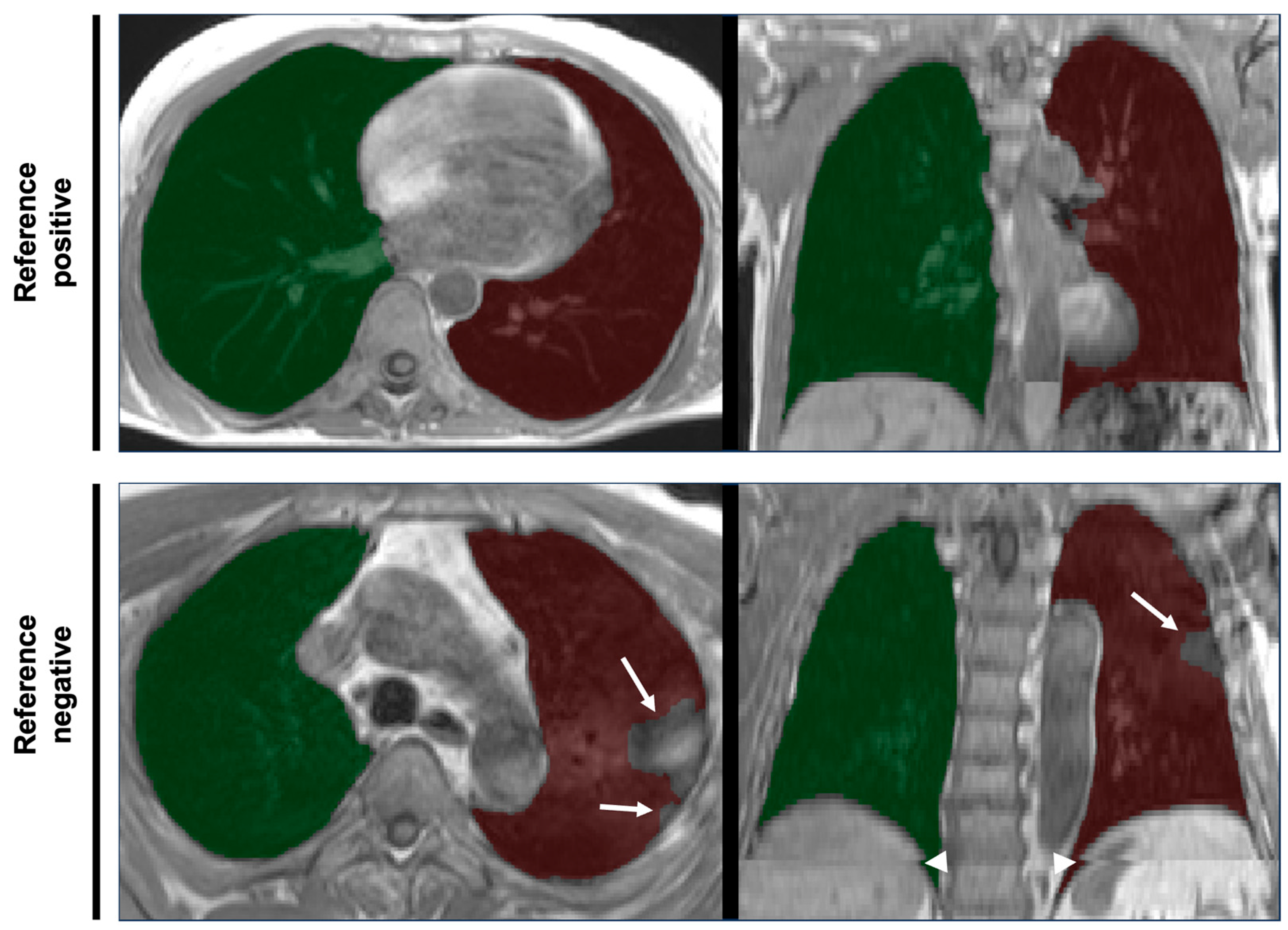

6]. In brief, lungs were covered in an axially acquired T1-weighted 3D VIBE two-point DIXON sequence of thorax and abdomen in inspiratory breath-hold (slice thickness 3.0 mm, voxel size in-plane 1.4 × 1.4 mm) using 3T MRI scanners (MAGNETOM Skyra, Siemens Healthineers AG, Forchheim, Germany). Examples are provided in

Figure 1.

2.3. Automated Lung Segmentation

Automated, deep learning-based lung segmentation was performed using the nnU-NET framework in 3D full resolution mode [

22]. Training of segmentation models was based on manual ground truth segmentations of stratified samples from NAKO (

n = 16) and COSYCONET (

n = 13) created by two medical experts. Right and left lungs were segmented separately and the lung hili excluded. The cases used for training of nnU-NET were not included in the present analysis of segmentation mask projection images. The training set size was determined heuristically, guided by the observed difficulty of the lung boundary delineation task. The objective was to establish reliable segmentation performance for the majority of the dataset, while allowing effective sampling of error cases for the presented quality control. Preprocessing was performed by nnU-Net. Specifically, images were cropped to regions containing non-zero intensities, resampled to a voxel spacing of

mm, and subjected to z-score normalization. Data augmentation was applied, comprising random rotation, scaling, elastic deformation, and gamma correction during training, and mirroring during training and application. No post-processing was performed. The U-Net architecture was configured using fundamental building blocks of 3 × 3 convolution, instance normalization and Leaky ReLU activations, with the number of feature channels ranging from 32 to 320. Training was performed using stochastic gradient descent with Nesterov momentum (0.99) and an initial learning rate of 0.01. The sum of cross-entropy and Dice loss was used as loss function. An ensemble of five networks was trained on disjoint subsets created through 5-fold cross-validation of the annotated images and subsequently used for inference. Train and test datasets were strictly separated on the subject level using unique subject identifiers.

2.4. Segmentation Mask Projection Images

Three different variants of projection images were created (Colored_MIP, Colored_outline, and Gray_outline), using either maximum intensity projection (MIP) of segmentation masks (Colored_MIP) or standard deviation projection of the isosurface between foreground and background voxels of the binary segmentation masks (Colored_outline, Gray_outline) of right and left lungs in axial and coronal orientation. For Colored_MIP and Colored_outline, a pseudo-chromadepth approach was chosen to improve depth perception [

23,

24,

25]. In order to also color-encode the labeling of right and left lung, two different color spectra for the right (mpl-viridis) and the left lung (mpl-plasma) were used in these cases. For projection, only slices containing lung voxels were selected in coronal and axial orientation. Resulting slice numbers were then linearly mapped to the respective color spectra. For comparison with grayscale projection images (Gray_outline), segmentation surface voxels were encoded in white and all other voxels in black. For subsequent z-stack projections using maximum intensity projection, each pixel of the resulting 2D image represents the maximum intensity of all voxels in the same x,y-position along the z-stack. In case of color-encoding, this refers to the maximum intensity per RGB-color channel. For standard deviation projections, the pixel values were calculated to represent the standard deviation of voxel intensities over the z-stack in the same position according to the formula

, where

Ii is the pixel intensity in slice

i of the current color channel of the z-stack,

μ is the mean of the pixel intensities along the z-stack, and

N is the number of slices in the z-stack. Axial and coronal projections were composed side by side to create a single panel for every segmentation mask. Projection images were created using FIJI (version 2.1.0/1.53c) and the Z-stack Depth Color Code plugin (version 0.0.2) [

26,

27]. The corresponding macro script used to generate the projection images is provided as

Supplemental Material.

2.5. Visual Segmentation Quality Assessment

Five raters (C.M., R.v.K., C.S., T.N., F.A.), of which four were radiologists and one (T.N.) a computer scientist with each at least 5 years of experience in lung imaging and segmentation, independently evaluated lung segmentation mask projections. Images were reviewed in random order in rapid succession using an in-house-developed web browser-based software that displayed axial and coronal projection images side by side on a 50% gray background, one case at a time. Left and right arrow keys on the computer keyboard were then used to rate the segmentation as either successful or erroneous. The next projection image was presented immediately after the rating of the last and respective ratings were automatically recorded for later analysis. Raters always evaluated the 300 cases in one continuous session per projection method. The total time required for each complete reading session was recorded manually by each rater and divided by 300 to calculate the average read time per case. Colored_outline images were rated first. The reads were repeated by all raters after a wash-out period of 1 week to assess intra-rater reliability. Gray_outline and then Colored_MIP images were rated after another wash-out interval of at least 2 weeks. The raters were blinded to any additional information and specifically instructed to “identify cases with any significant error in lung segmentation that hinders downstream analyses in the large MRI cohort study. Errors may include: incorrect anatomical segmentation, segmentation error due to possibly inadequate image quality, segmentation of non-lung structures (such as stomach), or the (partial) interchange of right and left lung labels. Swipe left in case of significant segmentation error, otherwise swipe right.”.

2.6. Reference Standard

One rater (R.v.K.) with more than 5 years of experience in lung imaging and research reviewed original DICOM data and an overlay of the corresponding segmentation masks using dedicated software (NORA Medical Imaging Platform Project, University Medical Center Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany). Slice-based review of the 3D segmentation masks for segmentation errors was performed using axial, coronal and sagittal view planes, and according to the same criteria used for projection images: errors that would significantly impact further analyses. Additionally, a second rater (C.M.) reviewed segmentation masks specifically for mislabeling of right and left lung, and any mislabeling was considered a significant segmentation error. Both raters conducted the review in random order, independently and blinded for the results of the other. Identified segmentation errors were assigned to the following categories: over-/under-segmentation of lung boundaries, exclusion of lung pathology, inclusion of distant organs, off-target stitching and partial or complete left–right mislabeling of the lungs. The worst rating of both reads was used for each case as the standard of reference. To avoid recall bias, as both raters were also involved in the evaluation of the index test, the ratings for reference standard and index test were separated by at least 6 months.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Normal distribution was assessed using QQ-plots and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Group comparisons were performed using Student’s

t-test or chi-squared test where appropriate. A receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) was created for each projection method over the sum of ratings of the five individual raters and corresponding areas under the curve (AUC) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals calculated according to the method by DeLong. Measures of diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, accuracy and F1-score) were calculated and confidence intervals calculated according to the Clopper–Pearson method. Sensitivities and specificities were compared using Cochran’s Q test for multiple classifiers followed by post hoc pairwise McNemar tests with Bonferroni adjustment of

p-values for multiple comparisons. Inter-rater reliability was calculated using Fleiss’ Kappa, and Cohen’s Kappa was used to assess intra-rater reliability. Kappa measures were interpreted as follows [

28]: <0.00 poor, 0.00–0.20 slight, 0.21–0.40 fair, 0.41–0.60 moderate, 0.61–0.80 substantial, 0.81–1.00 almost perfect. All statistical analyses were performed using R Version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

4. Discussion

We evaluated three 2D visualization techniques for visual quality control of deep learning-based 3D segmentations of the right and left lungs on whole-body MRI scans. Accuracies were highest for the methods using color-coding for right and left lung segmentation and depth along the z-axis with accuracies of 96.0% and 94.7% for Colored_MIP and Colored_outline images, respectively, based on five raters’ readings. Inter-rater reliability was almost perfect for both color-coding methods (0.87 and 0.82) and poor for Gray_outline (−0.01). Intra-rater reliability, assessed for the Colored_outline method, was also almost perfect for all 5 raters. The mean time required per case and rater varied between 1.7 s and 2.8 s.

Our observation, that color-coding resulted in higher accuracy compared to black-and-white coding for the detection of semantic segmentation errors when assessing a multilabel segmentation (left lung, right lung, background), was to be expected. This was further supported by our observation that 100% of cases with left–right mislabeling error were detected by the methods using color-coding, whereas Gray_outline only detected 88.5% of these cases. Of course, these errors can only be identified if the quality control method allows differentiation of the corresponding labels. However, we observed a large variability in the accuracy of Gray_outline images among the raters, with two raters performing notably worse. We hypothesize this may be related to a priori knowledge about the possibility of partially mislabeled right and left lung, leading to islands of left lung labels inside the right lung mask and vice versa. While the lack of color-coding prohibits direct identification of the assigned label, the segmentation mask outlines highlight these areas. Therefore, related to the predefined order in which the projection methods were evaluated, some raters possibly interpreted them as mislabeling. On the other hand, sensitivities for non-left–right mislabeling errors were still high in the majority of categories, especially for the second most frequent error type “over-/under-segmentation of lung boundaries”, with sensitivities between 79.4% and 85.3%.

Based on the sampling strategy used in our study, we found a much higher error rate of 63% in the sample stratum with the highest algorithm uncertainty and associated high sensitivities and specificities of the projection methods between 85.7–92.1% and 83.8–94.6%, respectively. In comparison, accuracy was lower in the strata with the majority of cases according to the uncertainty metric (median uncertainty) and those with the lowest uncertainty and correspondingly expectedly low error prevalence of 7%. However, sensitivities of 71.4% each and specificities of 100% and 98.9% for Colored_MIP and Colored_outline were still high in these scenarios and may still provide added benefit for identification of significant errors.

Few publications have previously reported on the use of visualization techniques for quality control of 3D biomedical image segmentation. Volume rendering has been used previously to improve the validation of automated semantic segmentation of confocal microscopy imaging data [

29]. However, the diagnostic performance of the resulting visualizations was not assessed. A recent publication on abdominal organ segmentation on MRI in two of the largest cohort studies, NAKO and UK Biobank, employed a similar approach to visual quality control, also incorporating MIP images of color-coded organ segmentation masks and underlying imaging data in axial, coronal and sagittal orientation [

2]. The images for quality control of 20.000 study participants were all reviewed by one rater. The authors did not report on the accuracy of the chosen approach compared to a slice-based review of the segmentations [

2]. Algorithm-derived methods for automated quality control of deep learning-based segmentations are being intensively investigated [

30,

31,

32]. These approaches depend on large training datasets and demonstrated high performance especially in cases of severe segmentation errors. But smaller segmentation errors may not be detected as effectively, which supports the notion of a multimodal approach to quality control [

33,

34]. Specifically, ensemble uncertainty-based metrics appear promising; however, this has so far been primarily demonstrated for non-segmentation approaches or with limited predictive value for the actual segmentation accuracy [

35,

36]. Some publications have reported on algorithmic approaches investigating anatomic plausibility of resulting segmentations to detect segmentation errors [

37] and point to an approach for segmentation quality control independent of underlying raw data, similar to the visual approach chosen in our study [

38,

39].

A recent publication presenting a new software tool for streamlined 3D slice-based review of medical imaging segmentations reported a review time for brain tumor segmentations on MRI of 11 s per case for one experienced radiation oncologist [

15]. While not directly comparable due to different organ and segmentation tasks, this indicates the potential time savings of the presented 2D projection methods. We used the majority rating of five raters to finally decide on the quality of the segmentation, which prolongs the overall time invested per case. However, manual 3D segmentation and review of automated segmentations also frequently involve more than one rater due to unavoidable inter-rater variability [

40]. Nevertheless, inter-rater reliability and accuracy were high for our proposed method and the investigated scenario and we believe the number of raters and potential correction–re-segmentation–re-evaluation cycles should be adjusted according to the specific use case.

A few limitations of this study have to be considered. The present evaluation of 2D projection images is limited to MRI-based segmentations of one pairwise organ of relatively simple shape. Diagnostic accuracy of the method may of course vary based on the specific segmentation task, anatomical region, segmentation algorithm and underlying imaging data. Generalizability of our findings is therefore limited. However, we feel color-coded projection images may be of potential use for any multilabel semantic seg-mentation task. Similarly, the variety of segmentation errors encountered will likely vary. While the observed sensitivity for non-left–right mislabeling errors varied between 50 and 100%, it has to be taken into account that some error categories were represented by only very few cases in our sample. Finally, we did not include the underlying imaging data in the visualizations and based our visual quality control approach solely on the subjective anatomical plausibility of the segmentation masks. This decision was based on a few example cases that led the authors to the impression that inclusion of the underlying imaging data in the projection images may not improve the process of visual quality control due to the increased complexity of the resulting images. Therefore, we believe the presented approach should not be interpreted as a single solution to the overall segmentation quality control problem of large-scale studies. Instead, a multi-rater visual quality control should complement algorithmically derived measures of segmentation accuracy and potentially slice-based spot-checking of segmentation results in small subsamples.