3D Imaging of Proton FLASH Radiation Using a Multi-Detector Small Animal PET System

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

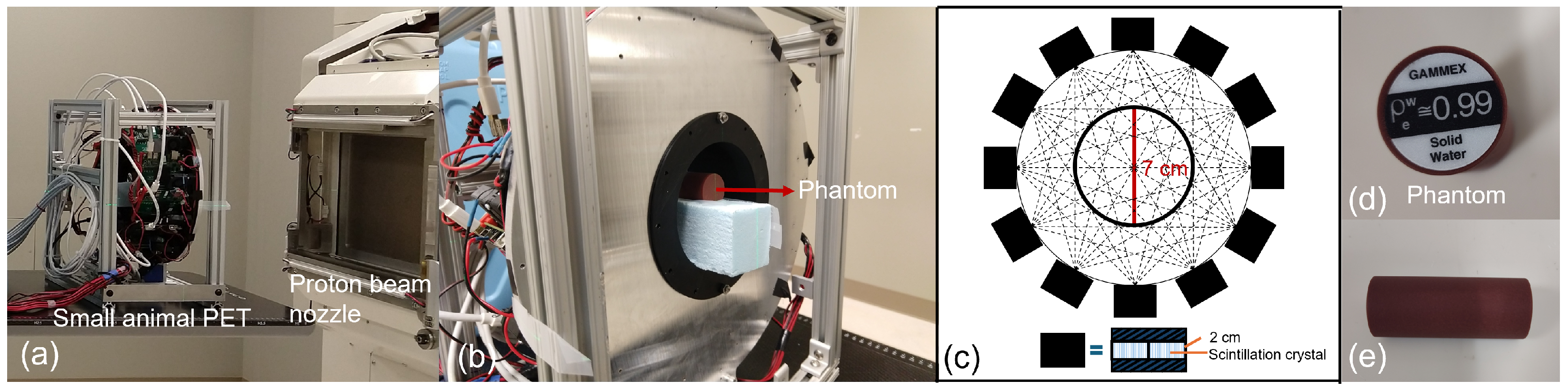

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.1.1. PET Imaging System

2.1.2. FLASH Proton Beam

2.1.3. Phantom

2.2. Study Design and Evaluation

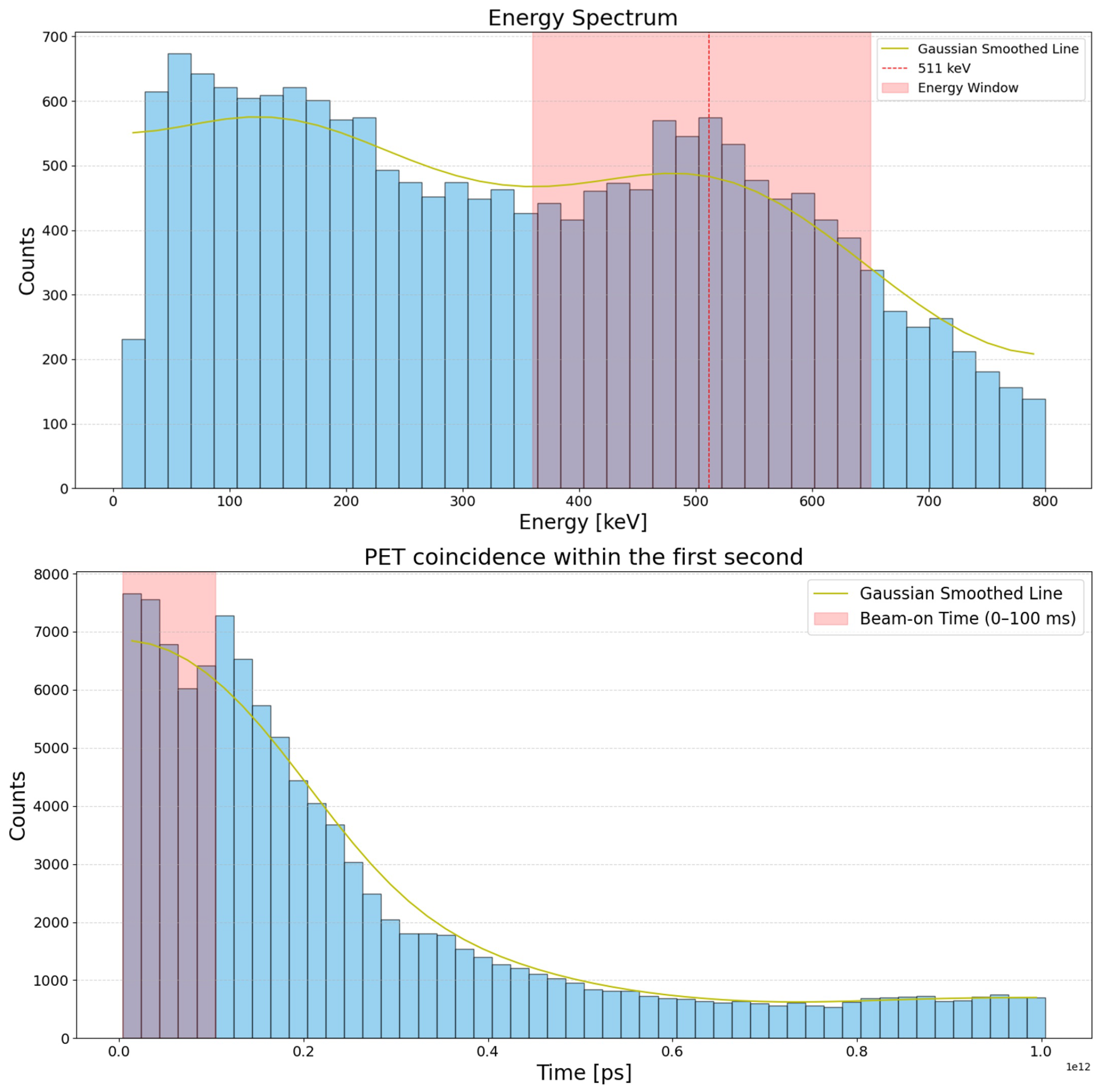

2.2.1. Time Distribution of PET Events

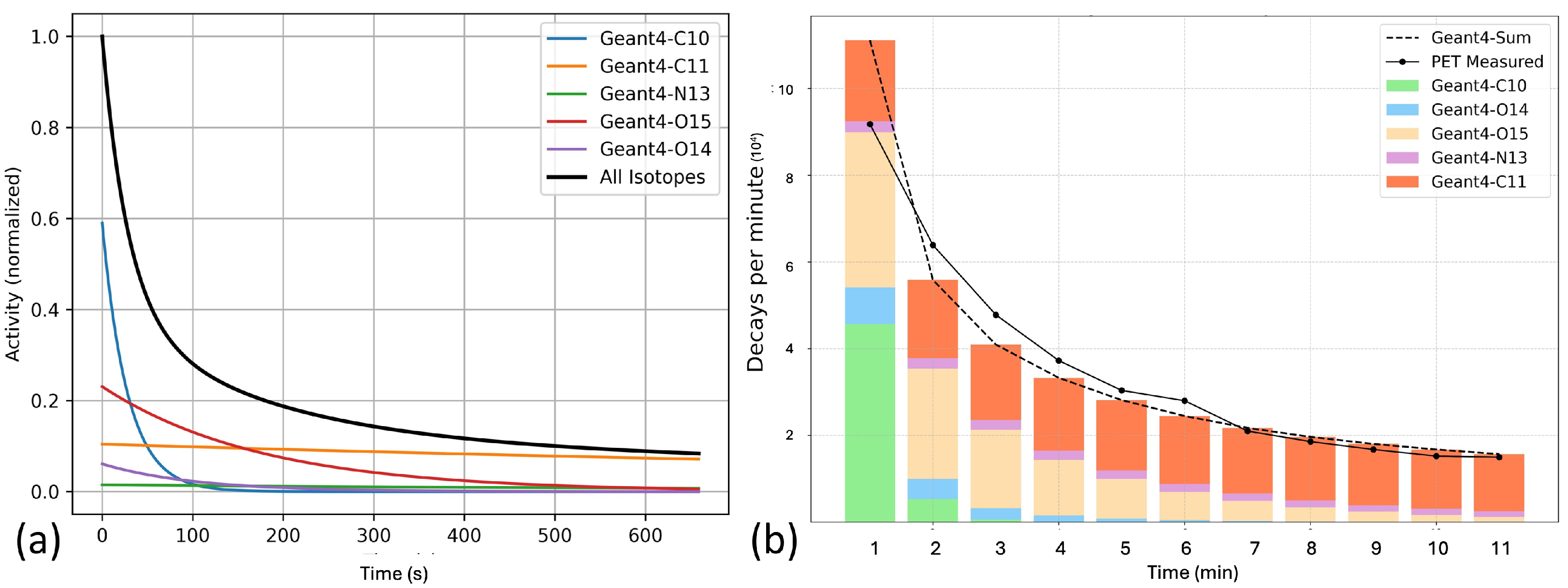

2.2.2. Monte Carlo Simulation

2.2.3. 3D Localization with the Multi-Detector PET System

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of PET Events During and Immediately After Irradiation

3.2. Characterization of PET Events Post Irradiation

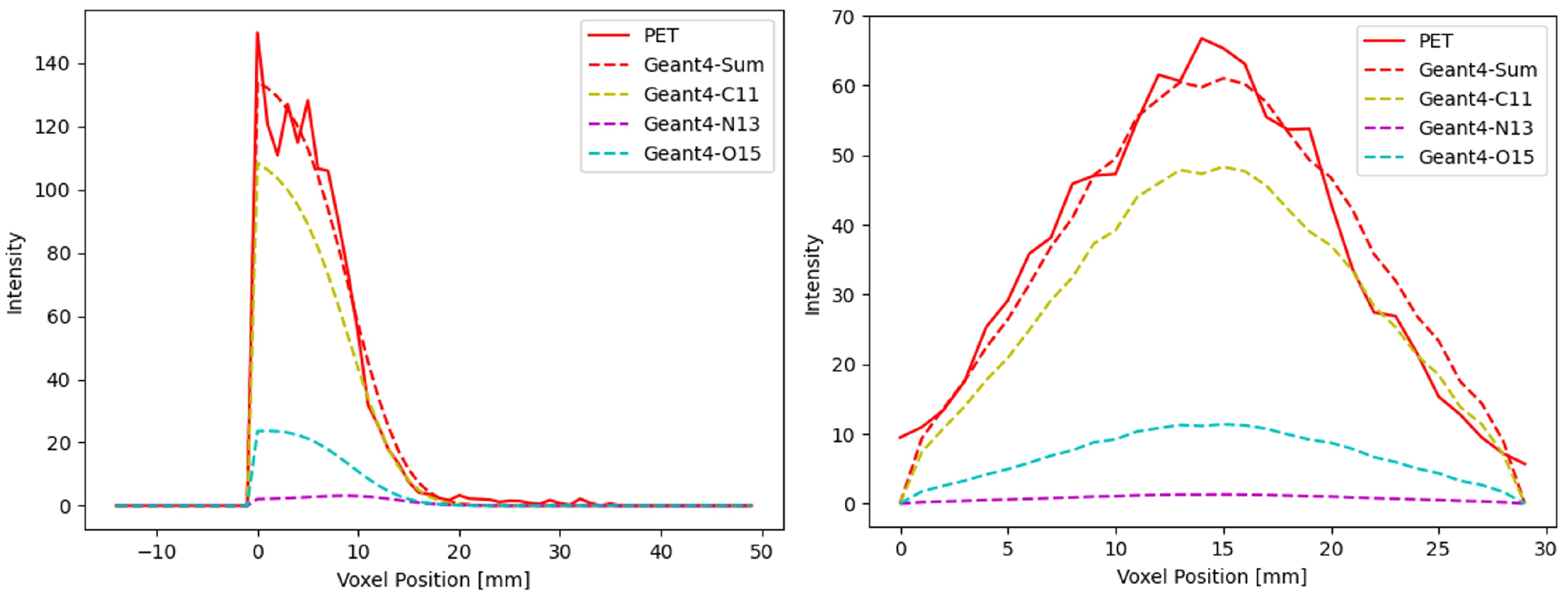

3.3. PET Image Reconstruction

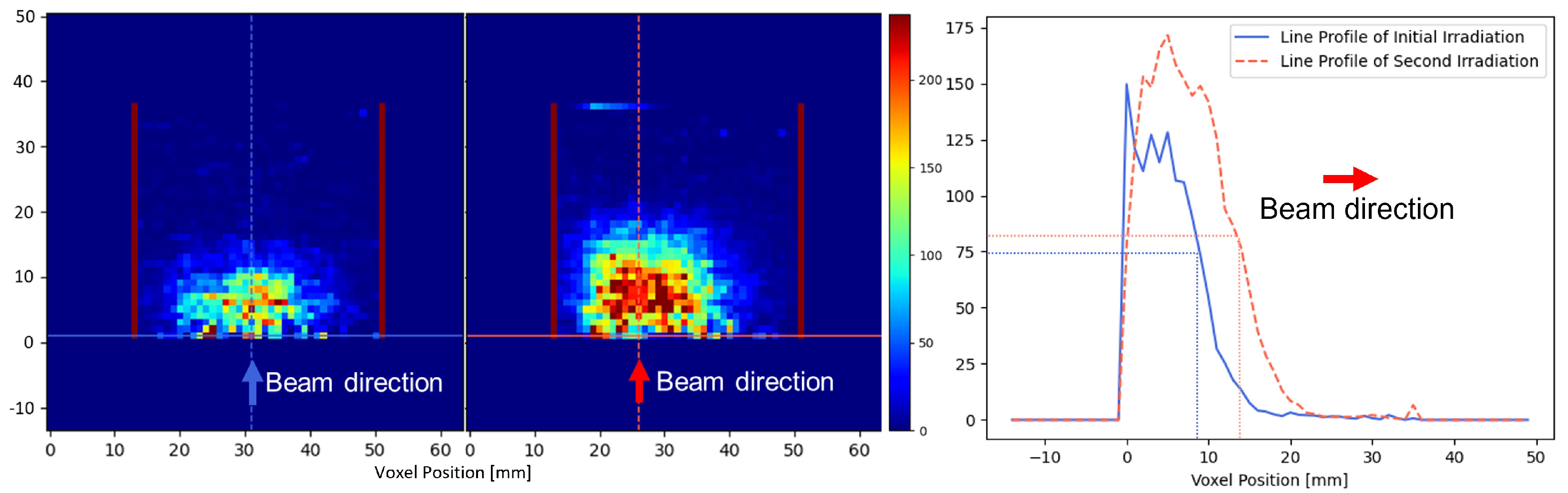

3.4. 3D Localization Capability Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bourhis, J.; Sozzi, W.J.; Jorge, P.G.; Gaide, O.; Bailat, C.; Duclos, F.; Patin, D.; Ozsahin, M.; Bochud, F.; Germond, J.F.; et al. Treatment of a first patient with FLASH-radiotherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2019, 139, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozenin, M.C.; Bourhis, J.; Durante, M. Towards clinical translation of FLASH radiotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.C.; Ruda, H.E. Mechanisms of action in FLASH radiotherapy: A comprehensive review of physicochemical and biological processes on cancerous and normal cells. Cells 2024, 13, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaudon, V.; Caplier, L.; Monceau, V.; Pouzoulet, F.; Sayarath, M.; Fouillade, C.; Poupon, M.F.; Brito, I.; Hupé, P.; Bourhis, J.; et al. Ultrahigh dose-rate FLASH irradiation increases the differential response between normal and tumor tissue in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 245ra93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascia, A.E.; Daugherty, E.C.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, E.; Xiao, Z.; Sertorio, M.; Woo, J.; Backus, L.R.; McDonald, J.M.; McCann, C.; et al. Proton FLASH radiotherapy for the treatment of symptomatic bone metastases: The FAST-01 nonrandomized trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, M.; di Martino, F.; Del Sarto, D.; Pensavalle, J.H.; Felici, G.; Giunti, L.; De Liso, V.; Kranzer, R.; Verona, C.; Rinati, G.V. A diamond detector based dosimetric system for instantaneous dose rate measurements in FLASH electron beams. Phys. Med. Biol. 2023, 68, 175011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaudon, V.; Lentz, J.M.; Heinrich, S.; Patriarca, A.; De Marzi, L.; Fouillade, C.; Dutreix, M. Time-resolved dosimetry of pulsed electron beams in very high dose-rate, FLASH irradiation for radiotherapy preclinical studies. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2019, 944, 162537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Ashraf, R.; Zhang, R.; Cao, X.; Gladstone, D.; Jarvis, L.; Hoopes, P.; Pogue, B.; Bruza, P. In Vivo Cherenkov Imaging-Guided FLASH Radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2022, 114, S139–S140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.R.; Rahman, M.; Zhang, R.; Williams, B.B.; Gladstone, D.J.; Pogue, B.W.; Bruza, P. Dosimetry for FLASH radiotherapy: A review of tools and the role of radioluminescence and Cherenkov emission. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casolaro, P.; Dellepiane, G.; Gottstein, A.; Mateu, I.; Scampoli, P.; Braccini, S. Time-resolved proton beam dosimetry for ultra-high dose-rate cancer therapy (FLASH). In Proceedings of the IBIC2022, Krakow, Poland, 11–15 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Charyyev, S.; Liu, R.; Yang, X.; Zhou, J.; Dhabaan, A.; Dynan, W.S.; Oancea, C.; Lin, L. Measurement of the time structure of FLASH beams using prompt gamma rays and secondary neutrons as surrogates. Phys. Med. Biol. 2023, 68, 145018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Lai, Y.; Yin, L.; Chi, Y.; Li, H.; Jia, X. Investigating radical yield variations in FLASH and conventional proton irradiation via microscopic Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Med. Biol. 2025, 70, 105012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Crespo, I.; Gómez, F.; Pouso, Ó.L.; Pardo-Montero, J. An in-silico study of conventional and FLASH radiotherapy iso-effectiveness: Potential impact of radiolytic oxygen depletion on tumor growth curves and tumor control probability. Phys. Med. Biol. 2024, 69, 215016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, R.; Esipova, T.V.; Allu, S.R.; Ashraf, R.; Rahman, M.; Gunn, J.R.; Bruza, P.; Gladstone, D.J.; Williams, B.B.; et al. Quantification of oxygen depletion during FLASH irradiation in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 111, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petusseau, A.F.; Clark, M.; Bruza, P.; Gladstone, D.; Pogue, B.W. Intracellular oxygen transient quantification in vivo during ultra-high dose rate FLASH radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2024, 120, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abouzahr, F.; Cesar, J.; Crespo, P.; Gajda, M.; Hu, Z.; Kaye, W.; Klein, K.; Kuo, A.; Majewski, S.; Mawlawi, O.; et al. The first PET glimpse of a proton FLASH beam. Phys. Med. Biol. 2023, 68, 125001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouzahr, F.; Cesar, J.; Crespo, P.; Gajda, M.; Hu, Z.; Klein, K.; Kuo, A.; Majewski, S.; Mawlawi, O.; Morozov, A.; et al. The first probe of a FLASH proton beam by PET. Phys. Med. Biol. 2023, 68, 235004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, K.; Ponisch, F.; Enghardt, W. Experimental study on the feasibility of in-beam PET for accurate monitoring of proton therapy. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2005, 52, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraan, A.C.; Berti, A.; Retico, A.; Baroni, G.; Battistoni, G.; Belcari, N.; Cerello, P.; Ciocca, M.; De Simoni, M.; Del Sarto, D.; et al. Localization of anatomical changes in patients during proton therapy with in-beam PET monitoring: A voxel-based morphometry approach exploiting Monte Carlo simulations. Med. Phys. 2022, 49, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Hu, K.; Yang, D.; Shao, Y. A High-performance Onboard Small Animal PET for Preclinical Radiotherapy Research. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference (NSS/MIC), Boston, MA, USA, 31 October–7 November 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Hu, K.; Yang, D.; Shao, Y. Design and development of a compact high-resolution detector for PET insert in small animal irradiator. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference (NSS/MIC), Boston, MA, USA, 31 October–7 November 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, L.; Masumi, U.; Ota, K.; Sforza, D.M.; Miles, D.; Rezaee, M.; Wong, J.W.; Jia, X.; Li, H. Feasibility of Synchrotron-Based Ultra-High Dose Rate (UHDR) Proton Irradiation with Pencil Beam Scanning for FLASH Research. Cancers 2024, 16, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Sforza, D.; Miles, D.; Masumi, U.; Ota, K.; Jia, X.; Li, H. Commissioning of a 142.4 MeV ultra-high dose rate (UHDR) proton beamline in a synchrotron-based proton therapy system. Med. Phys. 2025, 52, e18008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargett, M.A.; Briggs, A.R.; Booth, J.T. Water equivalence of a solid phantom material for radiation dosimetry applications. Phys. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 14, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinelli, S.; Allison, J.; Amako, K.a.; Apostolakis, J.; Araujo, H.; Arce, P.; Asai, M.; Axen, D.; Banerjee, S.; Barrand, G.; et al. Geant4—A simulation toolkit. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2003, 506, 250–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, J.; Amako, K.; Apostolakis, J.; Arce, P.; Asai, M.; Aso, T.; Bagli, E.; Bagulya, A.; Banerjee, S.; Barrand, G.; et al. Recent developments in Geant4. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2016, 835, 186–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Unholtz, D.; Kurz, C.; Parodi, K. An experimental approach to improve the Monte Carlo modelling of offline PET/CT-imaging of positron emitters induced by scanned proton beams. Phys. Med. Biol. 2013, 58, 5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espana, S.; Zhu, X.; Daartz, J.; El Fakhri, G.; Bortfeld, T.; Paganetti, H. The reliability of proton-nuclear interaction cross-section data to predict proton-induced PET images in proton therapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 2011, 56, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bethesda, M. Tissue Substitutes in Radiation Dosimetry and Measurement, Report 44 of the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements. J. ICRU 1989, os-23, iii-189. [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, T.; Stute, S.; Benoit, D.; Bert, J.; Carlier, T.; Comtat, C.; Filipovic, M.; Lamare, F.; Visvikis, D. CASToR: A generic data organization and processing code framework for multi-modal and multi-dimensional tomographic reconstruction. Phys. Med. Biol. 2018, 63, 185005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuyts, J.; Michel, C.; Dupont, P. Maximum-likelihood expectation-maximization reconstruction of sinograms with arbitrary noise distribution using NEC-transformations. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2001, 20, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Yang, Z.; Mu, D.; Gao, M.; Zhang, R.; Wan, L.; Qiu, A.; Xie, Q. In-beam PET monitoring of proton therapy: A method for filtering prompt radiation events. Phys. Med. Biol. 2024, 69, 125006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moglioni, M.; Kraan, A.C.; Baroni, G.; Battistoni, G.; Belcari, N.; Berti, A.; Carra, P.; Cerello, P.; Ciocca, M.; De Gregorio, A.; et al. In-vivo range verification analysis with in-beam PET data for patients treated with proton therapy at CNAO. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 929949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopf, A.C.; Lomax, A. In vivo proton range verification: A review. Phys. Med. Biol. 2013, 58, R131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganetti, H.; El Fakhri, G. Monitoring proton therapy with PET. Br. J. Radiol. 2015, 88, 20150173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, N.; Erickson, D.P.J.; Ford, E.C.; Emery, R.C.; Kranz, M.; Goff, P.; Schwarz, M.; Meyer, J.; Wong, T.; Saini, J.; et al. Preclinical ultra-high dose rate (FLASH) proton radiation therapy system for small animal studies. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2024, 9, 101425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffenderfer, E.S.; Sørensen, B.S.; Mazal, A.; Carlson, D.J. The current status of preclinical proton FLASH radiation and future directions. Med. Phys. 2022, 49, 2039–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesteruk, K.P.; Psoroulas, S. Flash irradiation with proton beams: Beam characteristics and their implications for beam diagnostics. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montay-Gruel, P.; Acharya, M.M.; Gonçalves Jorge, P.; Petit, B.; Petridis, I.G.; Fuchs, P.; Leavitt, R.; Petersson, K.; Gondré, M.; Ollivier, J.; et al. Hypofractionated FLASH-RT as an effective treatment against glioblastoma that reduces neurocognitive side effects in mice. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limoli, C.L.; Kramár, E.A.; Almeida, A.; Petit, B.; Grilj, V.; Baulch, J.E.; Ballesteros-Zebadua, P.; Loo, B.W., Jr.; Wood, M.A.; Vozenin, M.C. The sparing effect of FLASH-RT on synaptic plasticity is maintained in mice with standard fractionation. Radiother. Oncol. 2023, 186, 109767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourhis, J.; Montay-Gruel, P.; Jorge, P.G.; Bailat, C.; Petit, B.; Ollivier, J.; Jeanneret-Sozzi, W.; Ozsahin, M.; Bochud, F.; Moeckli, R.; et al. Clinical translation of FLASH radiotherapy: Why and how? Radiother. Oncol. 2019, 139, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, R.; Burnet, N.; Lowe, M.; Rothwell, B.; Kirkby, N.; Kirkby, K.; Hendry, J. FLASH radiotherapy: Considerations for multibeam and hypofractionation dose delivery. Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 164, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Technique/Method | Key Purpose or Measurement | Representative Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dosimetry (Time-resolved measurement) | Ionization chambers, diamond/plastic scintillator detectors | Characterize per-pulse and instantaneous dose rate under FLASH conditions | Marinelli et al. (2023) [6]; Favaudon et al. (2019) [7] |

| Optical methods | Cherenkov emission imaging | Provide real-time, pulse-to-pulse visualization of dose output in ultra-high dose-rate electron FLASH RT | Rahman et al. (2022) [8]; Ashraf et al. (2020) [9] |

| Prompt-gamma & secondary-radiation monitoring | Prompt-gamma timing and radiation signatures | Characterize temporal structure and dose-rate pattern of FLASH beams | Casolaro et al. (2022) [10]; Charyyev et al. (2023) [11] |

| Ultrafast radiolysis/Oxygen dynamics | Computational and experimental optical oximetry | Quantify radiolytic oxygen depletion and oxygen enhancement ratio during FLASH irradiation | Peng et al. (2025) [12]; González-Crespo et al. (2024) [13]; Cao et al. (2021) [14]; Petusseau et al. (2024) [15] |

| PET-based real-time beam tracking | Positron emission tomography (PET) with positron-emitting nuclei (11C, 15O, 13N, etc.) | Noninvasive verification of beam delivery and correlation of isotope distribution with dose-rate effects | Abouzahr et al. (2023a) [16]; Abouzahr et al. (2023b) [17] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Zhong, Y.; Lai, Y.; Yin, L.; Sforza, D.; Miles, D.; Li, H.; Jia, X. 3D Imaging of Proton FLASH Radiation Using a Multi-Detector Small Animal PET System. Tomography 2025, 11, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography11120131

Li W, Zhong Y, Lai Y, Yin L, Sforza D, Miles D, Li H, Jia X. 3D Imaging of Proton FLASH Radiation Using a Multi-Detector Small Animal PET System. Tomography. 2025; 11(12):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography11120131

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Wen, Yuncheng Zhong, Youfang Lai, Lingshu Yin, Daniel Sforza, Devin Miles, Heng Li, and Xun Jia. 2025. "3D Imaging of Proton FLASH Radiation Using a Multi-Detector Small Animal PET System" Tomography 11, no. 12: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography11120131

APA StyleLi, W., Zhong, Y., Lai, Y., Yin, L., Sforza, D., Miles, D., Li, H., & Jia, X. (2025). 3D Imaging of Proton FLASH Radiation Using a Multi-Detector Small Animal PET System. Tomography, 11(12), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography11120131