Design for Well-Being and Sustainability: A Conceptual Framework of the Peer-to-Peer Sharing and Reuse Platform in the Circular Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

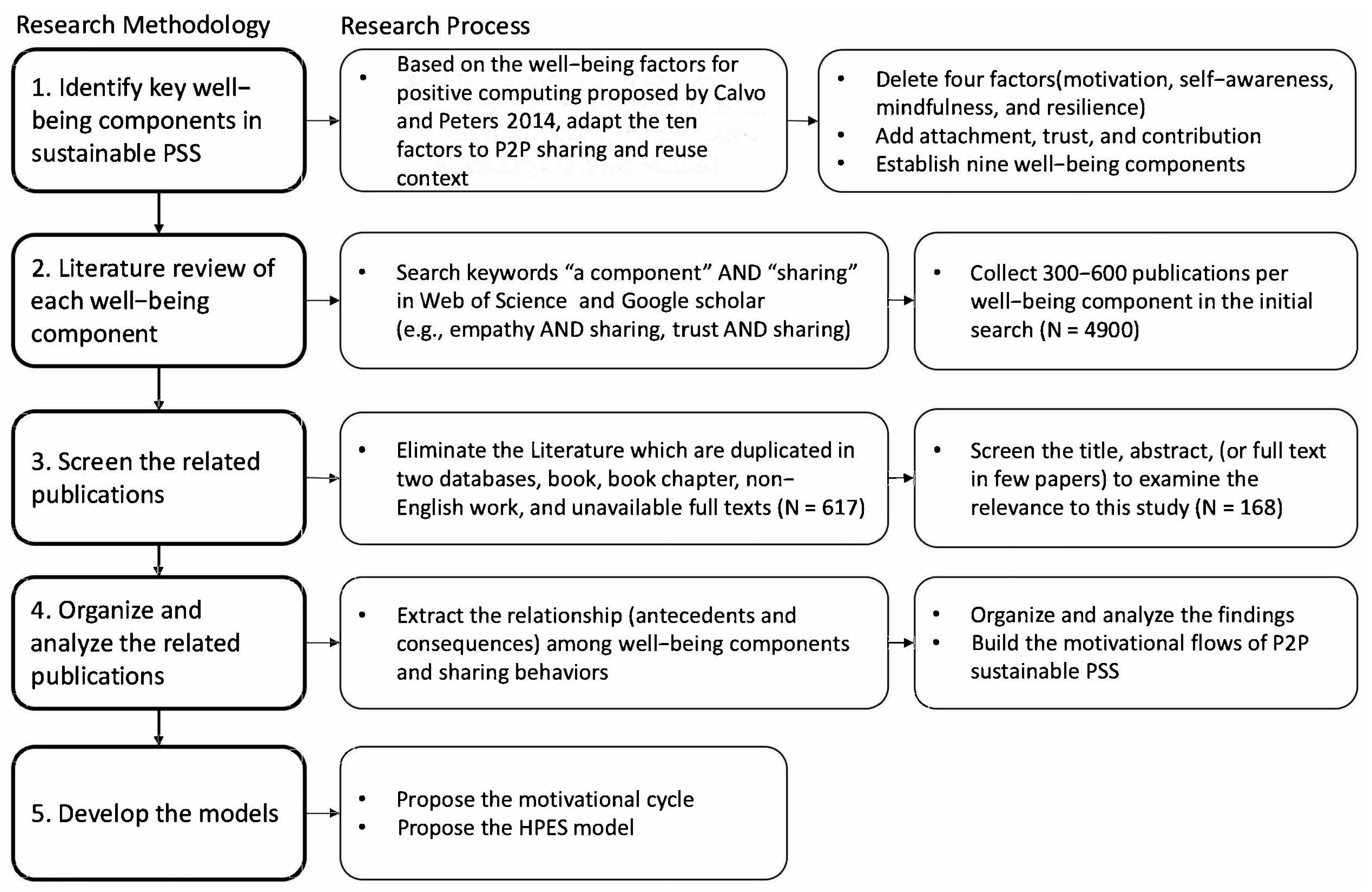

2. Research Methodology

3. Exploring Well-Being in a Sustainable Product–Service System

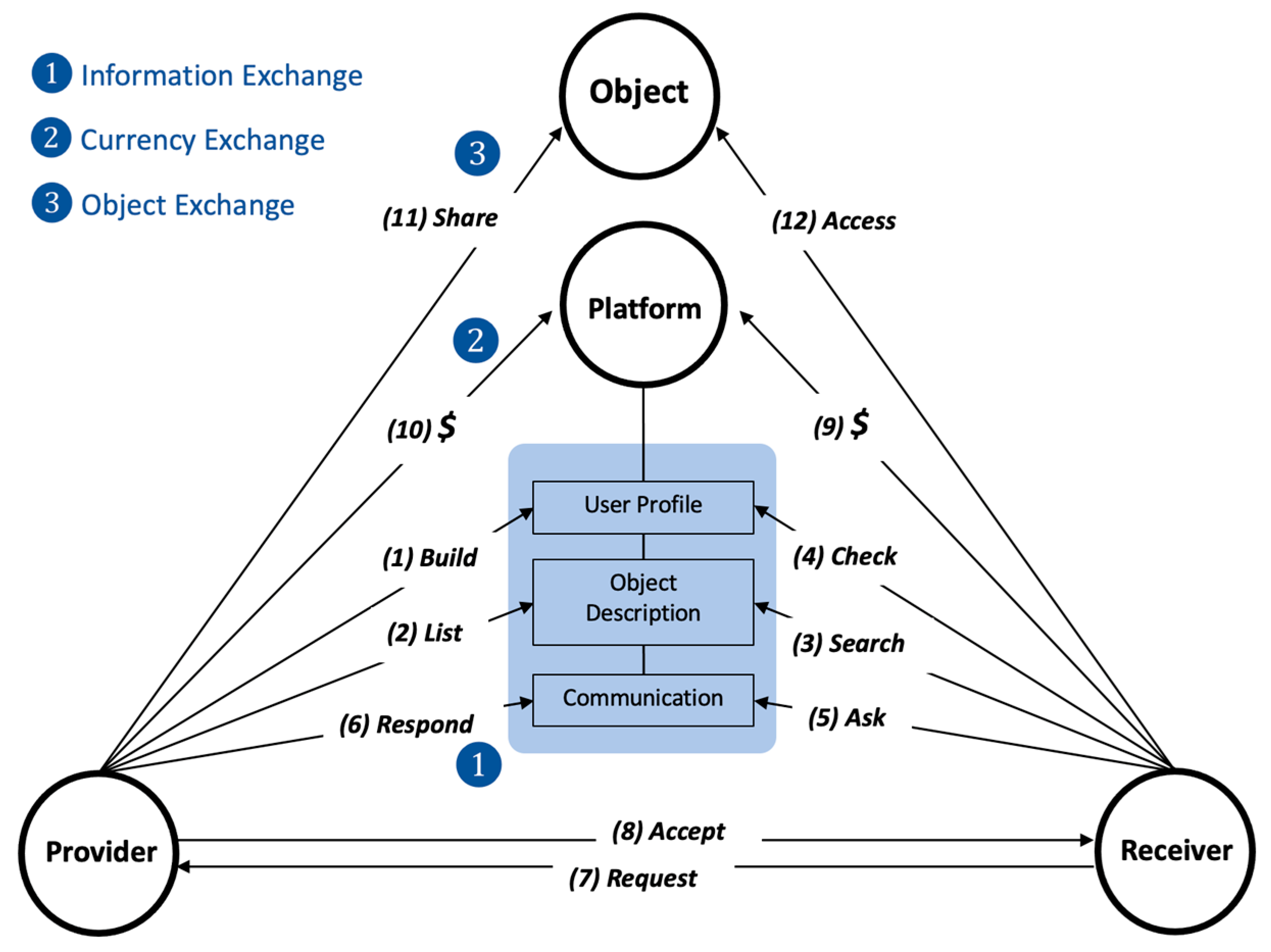

3.1. The Peer-to-Peer Sharing and Reuse Platform

3.2. How the Concept of Well-Being Works in Sharing and Reuse Contexts

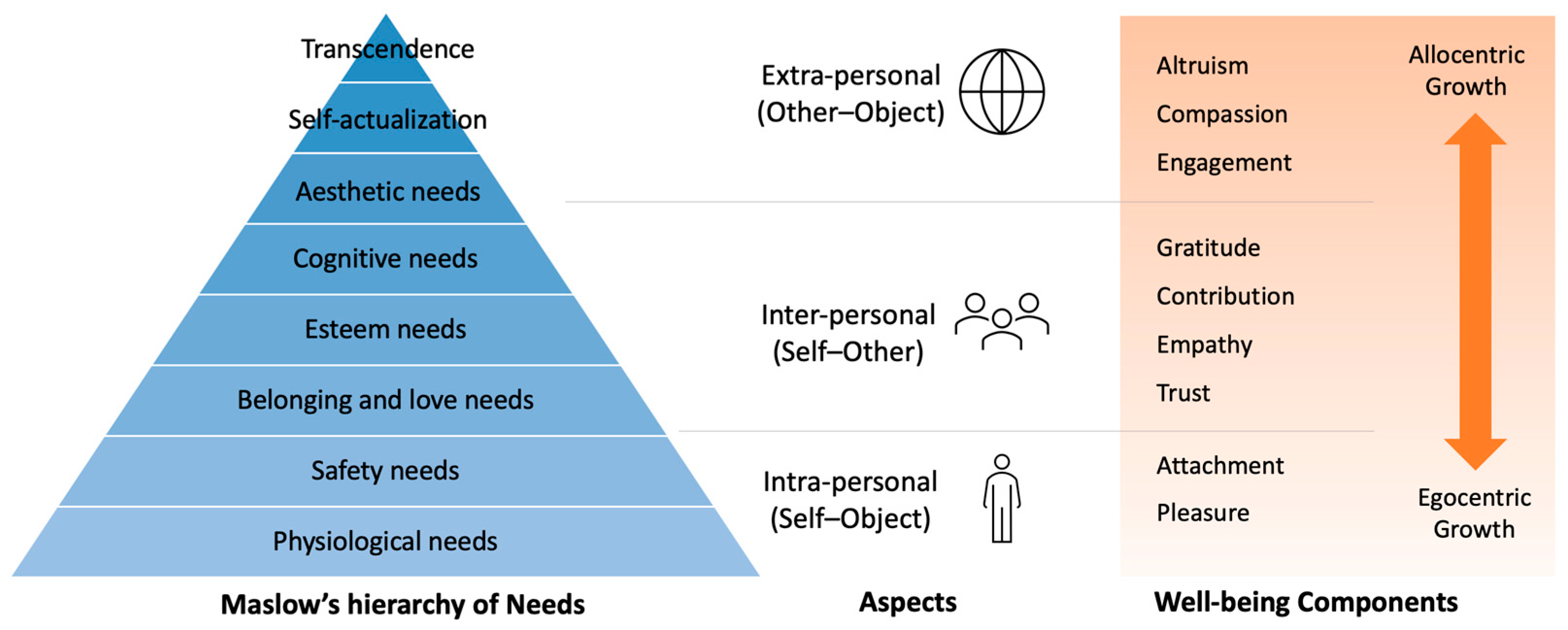

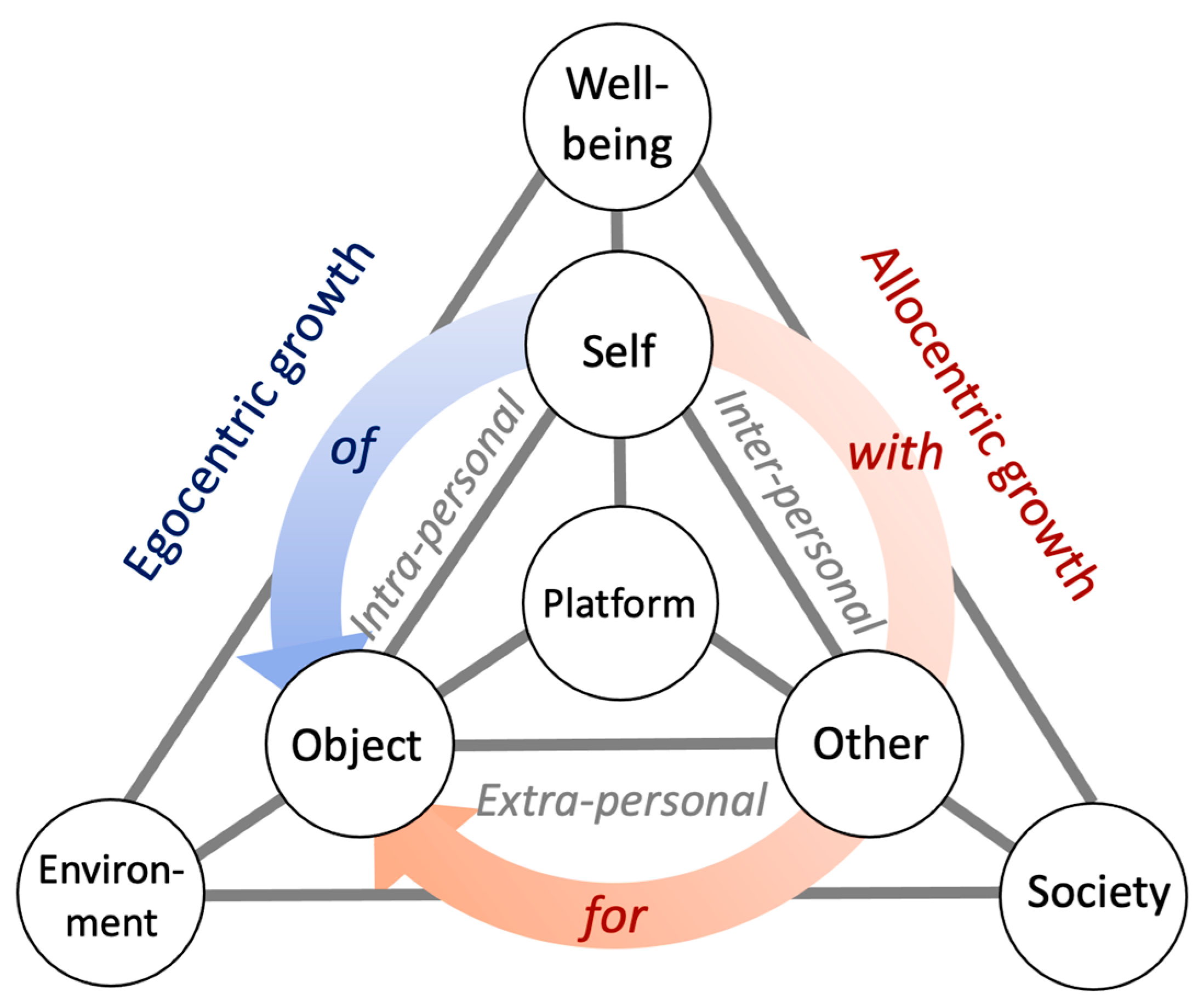

- Intra-personal: The well-being components are experienced within the self or with an inanimate object. The affective experience is independent of the presence of others, such as pleasure and attachment toward an object, which can be a product or service, tangible or intangible.

- Inter-personal: The well-being components depend on the interaction between the self and others. Through a P2P platform, users exchange and communicate with each other and experience positive affects (e.g., trust, empathy, gratitude).

- Extra-personal: The well-being components are transcendent concerns or actions for goods, beings, and cosmos beyond the self. In such an experience, one feels the unity of all things and aims to fulfill one’s full potential (e.g., engagement, compassion, and altruism).

- Pleasure: This is a positive influence that is fundamental and essential to the perception of well-being [44]. The need for pleasure ensures that animals are attracted to food, sex, or social interactions, leading to survival and reproduction [45]. Since owning and sharing possessions induces pleasure, scholars emphasize sharing and reusing rather than owning in the new era [46]. In addition, sharing tangible and intangible things generates pleasure. For example, sharing food online and offline facilitates social connections, and increases pleasure [47,48] and the appeal of food [48]. Furthermore, sharing home-grown food fosters social connections and motivates residents to share more [40]. By sharing intangible things (such as information, images, and ideas), people also feel the altruistic pleasure of helping others [47,49,50,51], etc.

- Attachment: This is the close bond developed between a baby and a mother (or a caregiver) through which the baby feels connected and secure [52]. In the sharing and reuse context, attachment can be extended toward inanimate things, such as an object or an environment. A strong attachment to an object motivates people to take good care of it and increases well-being [53]. Sellers who have a higher attachment to used products are more likely to offer discounts to buyers who will be able to use them appropriately [54]. For example, the presence of personal objects that evoke perceptions of the host’s presence can improve guests’ attachment to their hosts [55]. Attachment toward an accommodation can increase the intention to use recommendation sharing [56], etc.

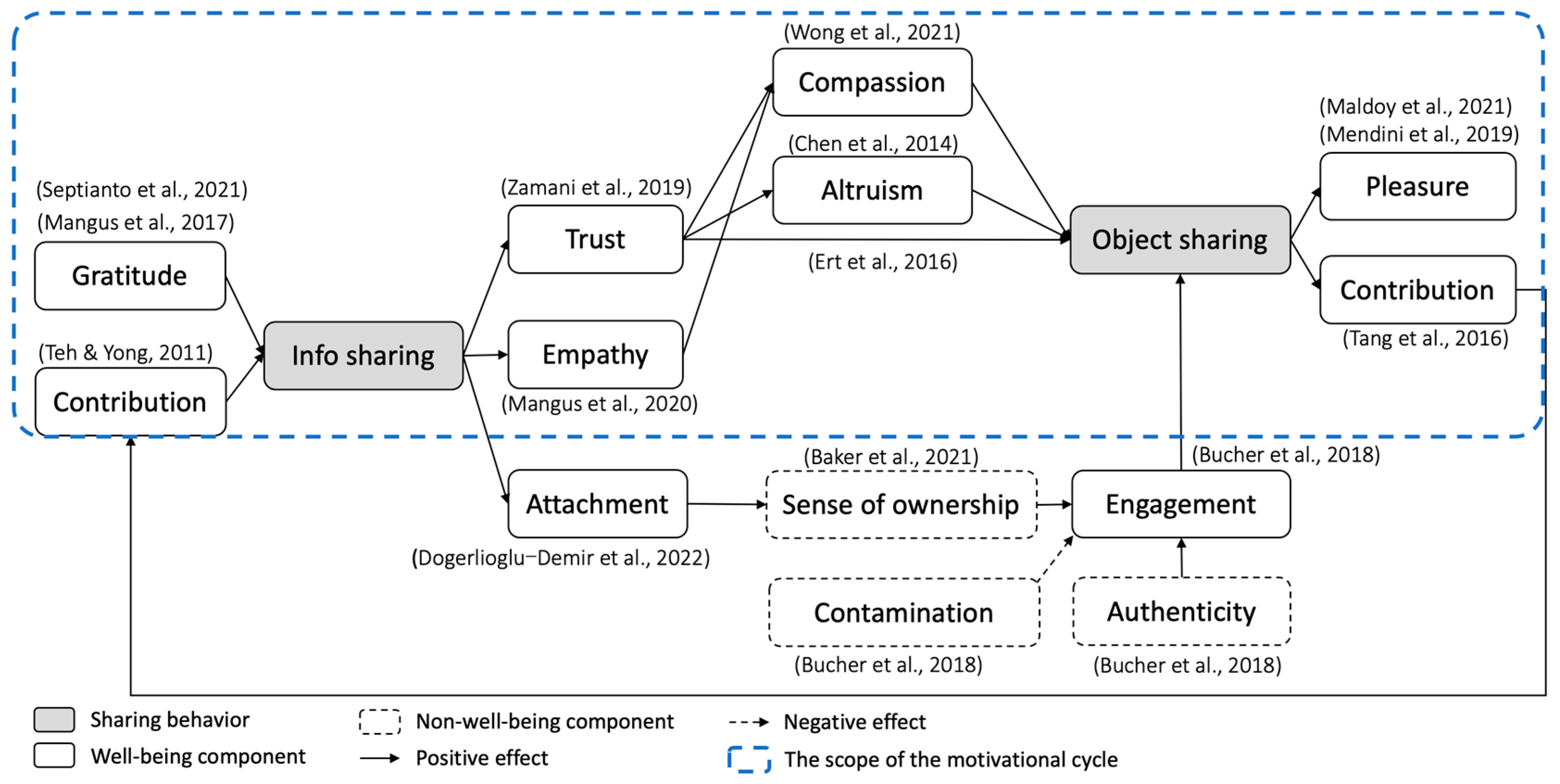

- Trust: This can be defined as an attitude in which a person relies on and believes another to behave as expected in an uncertain and vulnerable situation [57]. Trust allows people to perceive security, support, and comfort, and facilitates pro-social behavior [58]. It plays a crucial role in P2P platforms [59,60], where users share belongings with strangers, especially while sleeping at others’ homes [61,62,63,64,65]. Möhlmann and Geissinger [66] identify six design features that establish trust in the sharing economy: peer reputation, digitalized social capital, information provision, escrow services, insurance cover, and certification/external validation. Additionally, one study indicates that the quantity of information and communication between a provider and a receiver [65], the duration of self-description and diversity of topics of hosts in self-disclosure [36], and the humanization of profile pictures [38] are important factors to build trust. Moreover, the trustworthiness of the host’s personal photo increases the listing price and the probability of its being selected [35].

- Empathy: This is regarded as the mental process of eliciting emotions in response to others’ traits and conditions, as well as understanding the reasons behind these emotions [67]. Empathy is an emotional response based on the perception of others’ well-being [68]. In the sharing and reuse context, the empathy of receivers toward providers increases their willingness to make a purchase [69]. In addition, business and personal information disclosures between a seller and a buyer have a positive impact on empathy and business performance [70]. There is evidence that empathy prevents customers from leaving negative reviews [71,72].

- Contribution: The concept of contribution refers to a person’s positive impact on others and their fulfillment of the basic psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competence [73]. It can strongly predict the eudemonic well-being of oneself [74]. Concerning the sense of contribution in the sharing and reuse context, self-worth serves as an important intrinsic motivation to promote sharing of mobile coupons in social media [75]. Another study has shown that an organizational sense of contribution positively correlates with the intention of information system personnel to share knowledge [76].

- Gratitude: This is a feeling of appreciation when one receives favors, kindness, help, and support from others [77]. One can feel gratitude for not only inter-personal relationships but also for an object or an experience, such as artwork or a trip [78]. Research shows that practicing gratitude improves well-being (e.g., [79,80,81]). Gratitude appeal encourages word-of-mouth for sustainable luxury brands [82]. Furthermore, posting grateful reviews of firms will encourage other consumers to reward firms [83]. The gratitude between a salesperson and customer fosters the prosocial behaviors (e.g., information sharing) of a salesman, thus developing long-term buyer–seller relationships [84].

- Engagement: This refers to the state of being immersed in an activity or experience. It is also regarded as an optimal experience, “flow” [85,86]; moreover, it is defined as an exceptional and enjoyable experience that leads to the attainment of well-being [87]. Scholars indicate that a sense of ownership is the antecedent to engagement, including loyalty to a brand (or platform), contributions to its reputation, service functionality, and community-oriented sharing [88]. Additionally, inter-personal contamination (e.g., bad hygiene, intrusion of privacy) has negative effects on engagement in accommodation sharing, but the authenticity (e.g., providing more information about hosts, sharing their living space, and building a closer relationship between the host and the guest) can alleviate these negative effects, improving the engagement in sharing experiences [89,90].

- Compassion: This is an attitude of caring for others and a willingness to assist them in their suffering [91,92]. Additionally, treating oneself, others, and the environment with compassion improves individuals’ well-being and mental health [92,93,94]. Empathy and compassion are fundamental for the prosperity of social relationships. Furthermore, compassion enables people not only to share others’ emotions but also to help others [95]. According to a study, people who have high levels of trust and compassion for others are significantly more willing to share shelters and vehicles following disasters. In addition, the role of people (volunteers in past disasters and members of community organizations) rather than idle resources influences willingness to share [96].

- Altruism: This is regarded as a behavior rather than an emotion that gives benefits to others at the expense of oneself [97]. Altruism is based on empathy and compassion [68,98], which encompasses both inter-personal and extra-personal actions. In the sharing context, altruism and trust attract considerable attention. There is evidence that trust improves knowledge-sharing intentions, and altruism has a positive impact on the relationship between trust and knowledge-sharing intentions in teacher communities [99]. In particular, the trait of altruism impacts sharing intentions and lowers the need for trust [100]. Volunteers for the Wikipedia Foundation found that altruism motivates them to contribute to society continuously [101,102].

| Aspect | Component | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intra- personal | Pleasure | A positive effect that is fundamental to the perception of well-being [44]. | Sharing food and food experiences [47,48], information, images, ideas [47,49,50,51], etc. |

| Attachment | A close bond between a baby and a caregiver to feel connected and secure [52]. | Sharing accommodation [56], personal items [55], etc. | |

| Inter- personal | Trust | An attitude in which a person believes and relies on one another to behave as expected in an uncertain and vulnerable situation [57]. | Sharing accommodations [35,36,38,61,62,63,64,65], vehicles [103], information, knowledge [104,105], etc. |

| Empathy | A mental process in which emotions are elicited by others’ traits and conditions, and the reasons behind these emotions [67]. | Sharing accommodations [69], vehicles [70], information [71,72]., etc. | |

| Contribution | A positive impact on others that fulfills one’s human needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competence [73]. | Sharing mobile coupons [75], knowledge [76], etc. | |

| Gratitude | A feeling of thankfulness when one receives favors, kindness, help, and support from others [77]. | Sharing word-of-mouth [82], comments [83], sale information [84], etc. | |

| Extra- personal | Engagement | A state of being immersed in an activity or experience, and the optimal condition can be called a “flow” [85,86]. | Sharing accommodation [89,90], etc. |

| Compassion | A caring attitude and willingness to help others who are suffering [91,92]. | Sharing shelter, relief supplies [96], etc. | |

| Altruism | A behavior rather than an emotion, which benefits others at the expense of oneself [97]. | Sharing knowledge, expertise [99,100,101,102], etc. |

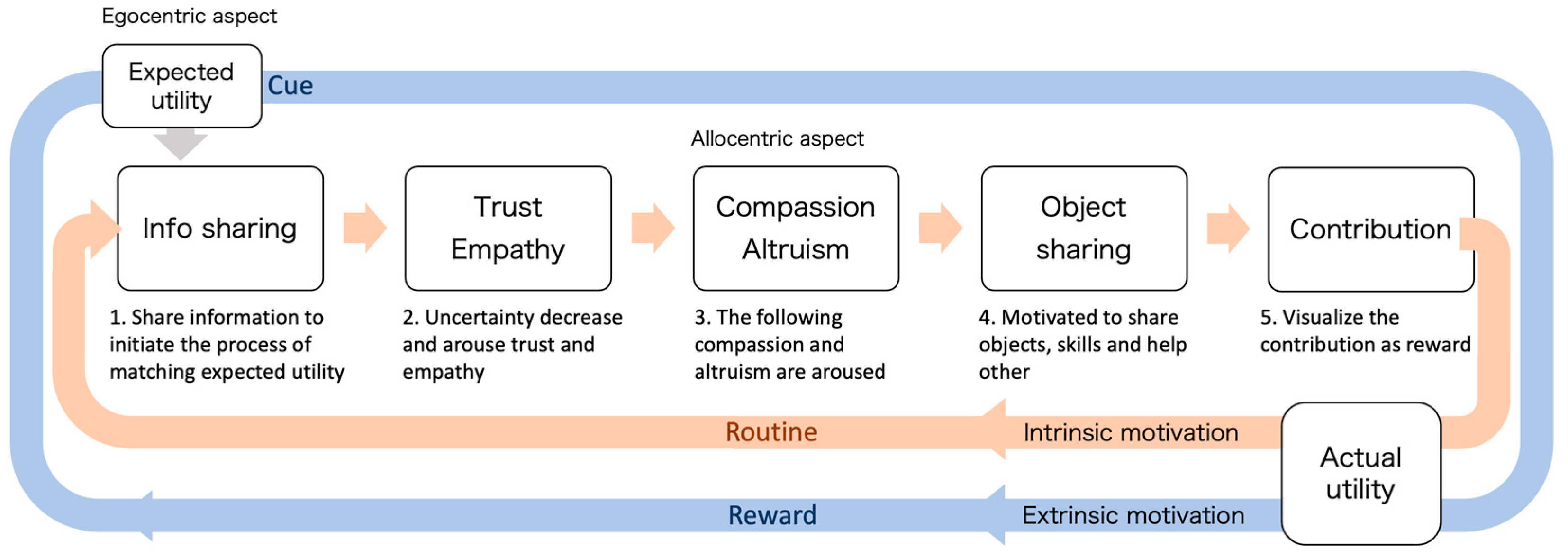

4. The Motivational Cycle of Well-Being in a Sustainable PSS

5. The Conceptual Framework of Well-Being in a Sustainable PSS

5.1. The Hyper-Pyramid-Eco-System Model (HPES Model)

5.2. Well-Being-Based Design Guidelines for P2P Sharing and Reuse Platform

- Pulling: This attracts providers and receivers to join in the sharing and reuse platforms, and regularly revisit them. In the beginning, it is challenging for a platform to attract users because of the “chicken-or-egg” problem, where users will not come to a platform if they feel there is no value, and a platform cannot create value without users [33]. Therefore, the platform design must address how to overcome this problem first and increase the number of users to initiate the network effect. The perception of contribution and gratitude are found to play significant roles in initiating users to share information when combined with the findings of the well-being components and the sharing behaviors. After sharing and reusing, people can perceive achievement and contribution naturally. Thus, platforms can encourage new providers to join the platform, with emphasis on contribution as well to facilitate circulation. For example, the commercials may focus on “contributing to society” instead of “saving cost”, and nudge users with messages, such as “Share knowledge with your colleagues, contribute to the whole campus”.

- Facilitating: This removes barriers and encourages value-creating interactions, such as sharing and collaboration. The mission is to ensure that the providers and receivers interact and exchange values properly. The well-designed platform adheres to the principles of transparency and insurance to ensure the safety of its users. Since platforms attract a wide range of users, they require governance and management to establish trust, equity, and security [33]. In the previous section, we found that information sharing is the key interaction between the two sides of users, serving as a pivot for allowing the users to get to know each other, engaging in social interaction, and developing a sense of well-being in the sharing platforms. Additionally, we conclude that information disclosure promotes trust and empathy. It is interesting to note that providers with a higher attachment toward objects intend to provide more benefits to receivers if they know that the receivers will treat their objects with care [54]. Since the receiver uses the shared objects appropriately, it reflects the sympathy and understanding between providers and receivers. Empathy serves as the key element to link the provider’s and the receiver’s mind. Therefore, we assume that empathy from receivers can arouse providers’ positive intentions and encourage them to disclose more information. In addition, trust and gratitude are found to positively impact users’ intentions to be “prosumers” on the sharing platforms [107]. It means that one-side users are more motivated to join the other side, i.e., a provider becomes a receiver and vice versa. Trust should be fostered to increase engagement among two sides of users in the sharing contexts. We believe it is not just the reputation score, but also the profile texts, personal photos, and communication, which create attached, reliable, and familiar experiences that can influence how others trust and develop empathy. Moreover, communication between a provider and a receiver is crucial to increase empathy and altruism, especially when a receiver asks questions instead of receiving one-way communication from a provider [108]. Therefore, we suggest that the design of the user profile, object description, and communication should nudge users to have more well-being-based information sharing to arouse positive perceptions.

- Matching: It builds an efficient mechanism to match the relevant providers to receivers. The platforms accurately match the needs of users with objects or services based on the information provided by them. The information can be statistical (such as gender, nationality) or dynamic (such as date, location). Additionally, platforms utilize a large amount of data to refine matching algorithms and filter the information exchange between providers and receivers [33]. We suggest the platform design should be devoted to matching users who experience more empathy and trust. For example, similar background users can arouse more empathy, and people who have more authentic self-disclosure can increase trust. After a provider and a receiver share information, as well as build trust and empathy toward each other, the perception of compassion and altruism can be aroused as follows. Users maximize the utility for not only their own benefits, but also the well-being of objects, society, and the environment. Thus, the platform should support users to increase positive interactions, and maximize utility through sharing and reusing objects. Finally, the well-being-based guidelines can arouse behavior changes in users from exchanging information, reusing, and sharing an object, to engaging sustainably.

6. Prospective Approaches for Modeling Well-Being Components in a Sustainable PSS

6.1. Data-Driven Approach

6.2. Computational Neuroscience Approach

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rume, T.; Islam, S.D.-U. Environmental effects of COVID-19 pandemic and potential strategies of sustainability. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everingham, P.; Chassagne, N. Post COVID-19 ecological and social reset: Moving away from capitalist growth models towards tourism as Buen Vivir. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wong, Y.D.; Yuen, K.F. Rise of ‘lonely’consumers in the post-COVID-19 era: A synthesised review on psychological, commercial and social implications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrington-Leigh, C. Sustainability and Well-Being: A Happy Synergy; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Archambault, N. Staying Connected in a World of Physical Distancing; ASHA leader: Rockville, MD, USA, 2020; Volume 25, pp. 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, S.E. A social skill account of problematic Internet use. J. Commun. 2005, 55, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Aznar, E.T. Business and labour culture changes in digital paradigm: Rise and fall of human resources and the emergence of talent development. Cogito 2020, 12, 225–243. (In English). Available online: https://go.exlibris.link/8VgQ55sq (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Frenken, K. Sustainability perspectives on the sharing economy. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 23, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzoli, C.; Ceschin, F.; Diehl, J.C.; Kohtala, C. New design challenges to widely implement ‘Sustainable Product–Service Systems’. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, U.M.; Davis, M.M. Sharing economy services: Business model generation. Calif. Manag. 2019, 61, 104–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.; So, K.K.F.; Mody, M.A.; Liu, S.Q.; Chun, H.H. Platforms in the peer-to-peer sharing economy. J. Serv. Manag. 2019, 30, 452–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; Collins: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R. Sharing versus pseudo-sharing in Web 2.0. Anthropologist 2014, 18, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, G.M.; Bardhi, F. The sharing economy isn’t about sharing at all. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 28, 881–898. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, T.S.; Lightfoot, H.W.; Evans, S.; Neely, A.; Greenough, R.; Peppard, J.; Roy, R.; Shehab, E.; Braganza, A.; Tiwari, A.; et al. State-of-the-art in product-service systems. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part. B J. Eng. Manufact. 2020, 221, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüher, T.; Riedelsheimer, T.; Gogineni, S.; Klemichen, A.; Stark, R. Systematic Literature Review-Effects of PSS on Sustainability Based on Use Case Assessments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, V.; Ambard, A.; Turner, C.; Gossmann, K.; Demkova, K.; Carroll, J.M. A muddle of models of motivation for using peer-to-peer economy systems. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 18–23 April 2015; pp. 1085–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, D.; Lafontaine, P.R.; Hendrickson, B. CouchSurfing: Belonging and trust in a globally cooperative online social network. New Media Soc. 2011, 13, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, H.; Wu, X.; Ueda, K.; Kato, T. Free energy model of emotional valence in dual-process perceptions. Neu Netw. 2023, 157, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, H. Free-energy model of emotion potential: Modeling arousal potential as information content induced by complexity and novelty. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 698252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Praag, B.M.; Frijters, P.; Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. The anatomy of subjective well-being. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2003, 51, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Praag, B.M.; Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. Happiness economics: A new road to measuring and comparing happiness. Found. Trends Microecon. 2011, 6, 1–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, R.A.; Peters, D. Positive Computing: Technology for Wellbeing and Human Potential; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Jing, S.; Nie, Z.; Zhao, B.; Tan, R. Design and development of sustainable product service systems based on design-centric complexity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsini, L.; Moultrie, J. What Is Design for Social Sustainability? A Systematic Literature Review for Designers of Product-Service Systems. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, J. Debating the Sharing Economy. J. Self-Govern. Manag. Ecol. 2016, 4, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Sjoklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, A. The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt, G.M.; Houston, M.B.; Jiang, B.; Lamberton, C.; Rindfleisch, A.; Zervas, G. Marketing in the sharing economy. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Schor, J. Putting the sharing economy into perspective. In A Research Agenda for Sustainable Consumption Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gerwe, O.; Silva, R. Clarifying the sharing economy: Conceptualization, typology, antecedents, and effects. Acad. Manag. Perspet. 2020, 34, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.G.; Van Alstyne, M.W.; Choudary, S.P. Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy and How to Make Them Work for You; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Perren, R.; Kozinets, R.V. Lateral exchange markets: How social platforms operate in a networked economy. J. Mark. 2018, 82, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ert, E.; Fleischer, A.; Magen, N. Trust and reputation in the sharing economy: The role of personal photos in Airbnb. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 62–73. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Hancock, J.T.; Lim Mingjie, K.; Naaman, M. Self-disclosure and perceived trustworthiness of Airbnb host profiles. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Portland, OR, USA, 25 February 2017; pp. 2397–2409. [Google Scholar]

- Teubner, T.; Hawlitschek, F.; Dann, D. Price determinants on Airbnb: How reputation pays off in the sharing economy. J. Self-Govern. Manag. Econ. 2017, 5, 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Teubner, T.; Adam, M.T.; Camacho, S.; Hassanein, K. Understanding resource sharing in C2C platforms: The role of picture humanization. In Proceedings of the 25th Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Auckland, New Zealand, 8–10 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Simon and Schuster: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, G.; Prilleltensky, I. Community Psychology: In Pursuit of Liberation and Well-Being; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. Toward a Psychology of Being; Simon and Schuster: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach, M.L. The Hedonic Brain: A Functional Neuroanatomy of Human Pleasure; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life; Books, Incorporated: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1859. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R. Why Not Share Rather than Own? Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 2007, 611, 126–140. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendini, M.; Pizzetti, M.; Peter, P.C. Social food pleasure: When sharing offline, online and for society promotes pleasurable and healthy food experiences and well-being. Qual. Mark. Res. 2019, 22, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldoy, K.; De Backer, C.J.S.; Poels, K. The pleasure of sharing: Can social context make healthy food more appealing? Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 359–370. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.F. Knowledge sharing and firm innovation capability: An empirical study. Int. J. Manpow. 2007, 28, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, Y.S.; Kim, H.; Lee, Y.-G.; Kim, B. The effects of individual motivations and social capital on employees’ tacit and explicit knowledge sharing intentions. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2013, 33, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, A.M.; Jacobsen, J.K.S. Motivations for sharing tourism experiences through social media. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tsurumi, T.; Yamaguchi, R.; Kagohashi, S. Managi. Attachment to material goods and subjective well-being: Evidence from life satisfaction in rural areas in Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, A.R.; Isaac, M.S. Finding a Home for Products We Love: How Buyer Usage Intent Affects the Pricing of Used Goods. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 78–91. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogerlioglu-Demir, K.; Akpinar, E.; Ceylan, M. Combating the fear of COVID-19 through shared accommodations: Does perceived human presence create a sense of social connectedness? J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 400–413. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gursoy, D. Exploring the relationship between servicescape, place attachment, and intention to recommend accommodations marketed through sharing economy platforms. J. Trav. Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.D.; See, K.A. Trust in automation: Designing for appropriate reliance. Hum. Fact. 2004, 46, 50–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Wang, S. Trust and Well-Being; National Bureau of Economic Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hawlitschek, F.; Teubner, T.; Weinhardt, C. Trust in the sharing economy. Unternehmung 2016, 70, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parigi, P.; Cook, K. Trust and relationships in the sharing economy. Contexts 2015, 14, 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Räisänen, J.A.; Ojala, T. Tuovinen. Building trust in the sharing economy: Current approaches and future considerations. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Asaad, Y.; Filieri, R. What makes hosts trust Airbnb? Antecedents of hosts’ trust toward Airbnb and its impact on continuance intention. J. Trav. Res. 2020, 59, 686–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.E.; Jones, M.F.; Li, M.; Wei, W.; Lyu, J. Sleeping in a stranger’s home: A trust formation model for Airbnb. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, N.M.; Sun, E.; Antin, J.; Parigi, P. Designing for Trust: A Behavioral Framework for Sharing Economy Platforms. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2020, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–24 April 2020; pp. 2133–2143. [Google Scholar]

- Zamani, E.D.; Choudrie, J.; Katechos, G.; Yin, Y. Trust in the sharing economy: The AirBnB case. Indust. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 1947–1968. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhlmann, M.; Geissinger, G. Trust in the sharing economy: Platform-mediated peer trust. In Cambridge Handbook of the Law of the Sharing Economy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cuff, B.M.; Brown, S.J.; Taylor, L.; Howat, D.J. Empathy: A review of the concept. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Ahmad, A.; Lishner, D.A.; Tsang, J.; Snyder, C.; Lopez, S. Empathy and altruism. In The Oxford Handbook of Hypo-Egoic Phenomena; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 485–498. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, J.P.; Reczek, R.W. Providers versus platforms: Marketing communications in the sharing economy. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 22–38. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangus, S.M.; Bock, D.E.; Jones, E.; Folse, J.A.G. Examining the effects of mutual information sharing and relationship empathy: A social penetration theory perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pera, R.; Viglia, G.; Grazzini, L.; Dalli, D. When empathy prevents negative reviewing behavior (as it does in English). Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieseke, J.; Geigenmüller, A.; Kraus, F. On the role of empathy in customer-employee interactions. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of benevolence: Basic psychological needs, beneficence, and the enhancement of well-being. J. Pers. 2016, 84, 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Huta, V.; Deci, E.L. Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. J. Happ. Stud. 2006, 9, 139–170. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Liu, S. The effect of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations on mobile coupon sharing in social network sites: The role of coupon proneness. Internet. Res. 2016, 26, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, P.-L.; Yong, C.-C. Knowledge Sharing in is Personnel: Organizational Behavior’s Perspective. J. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2011, 51, 11–21. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Tesser, A.; Gatewood, R.; Driver, M. Some determinants of gratitude. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1968, 9, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, R.A.; Sansone, L.A. Gratitude and well being: The benefits of appreciation. Psychiatry 2010, 7, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerhoof, R.M. Expressing Optimism and Gratitude: A Longitudinal Investigation of Cognitive Strategies to Increase Well-Being; University of California: Riverside, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Froh, J.J.; Sefick, W.J.; Emmons, R. Counting blessings in early adolescents: An experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. J. School Psychol. 2008, 46, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; Froh, J.J.; Geraghty, A.W. Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septianto, Y.; Seo, A.C. Errmann. Distinct effects of pride and gratitude appeals on sustainable luxury brands. J. Bus. Eth. 2021, 169, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, D.; Thomas, V.; Wolter, J.; Saenger, C.; Xu, P. An extended reciprocity cycle of gratitude: How gratitude strengthens existing and initiates new customer. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 564576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangus, S.M.; Bock, E.; Jones, J.A.G. Gratitude in buyer-seller relationships: A dyadic investigation. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2017, 37, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Flow, F. The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schueller; Seligman. Pursuit of pleasure, engagement, and meaning: Relationships to subjective and objective measures of well-being. J. Pos. Psychol. 2010, 5, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.J.; Kearney, T.; Laud, G.; Holmlund, M. Engaging users in the sharing economy: Individual and collective psychological ownership as antecedents to actor engagement. J. Serv. Manag. 2021, 32, 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulauskaite, D.; Powell, R.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.; Morrison, A.M. Living like a local: Authentic tourism experiences and the sharing economy. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, E.; Fieseler, C.; Fleck, M.; Lutz, C. Authenticity and the sharing economy. Acad. Manag. Disc. 2018, 4, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierhoff, H.-W. The psychology of compassion and prosocial behaviour. In Compassion; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 160–179. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, C.; Taylor, B.L.; Gu, J.; Kuyken, W.; Baer, R.; Jones, F.; Cavanagh, K. What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 47, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Sassenrath, C.; Schindler, S. Feelings for the suffering of others and the environment: Compassion fosters proenvironmental tendencies. Environ. Beg. 2016, 48, 929–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.; Sanderman, S.; Ranchor, A.V.; Schroevers, M.J. Compassion for others and self-compassion: Levels, correlates, and relationship with psychological well-being. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Waal, F. The Age of Empathy: Nature’s Lessons for a Kinder Society; Broadway Books: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S.D.; Walker, J.L.; Shaheen, S.A. Trust and compassion in willingness to share mobility and sheltering resources in evacuations: A case study of the 2017 and 2018 California Wildfires. Int. J. Disast. Risk. Reduct. 2021, 52, 101900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Fischbacher, U. The nature of human altruism. Nature 2003, 425, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.L. Is altruism part of human nature? J. Physiol. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 40, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-L.; Fan, H.-L.; Tsai, C.-C. The role of community trust and altruism in knowledge sharing: An investigation of a virtual community of teacher professionals. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2014, 17, 168–179. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.-L.; Lin, C.-H.; Hsu, B.-F.; Yeh, R.-S. Interpersonal trust and knowledge sharing: Moderating effects of individual altruism and a social interaction environment. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2009, 37, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baytiyeh, H.; Pfaffman, J. Volunteers in Wikipedia: Why the community matters. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2010, 13, 128–140. [Google Scholar]

- Prasarnphanich, P.; Wagner, C. The role of wiki technology and altruism in collaborative knowledge creation. J. Comput. Inform. Cyst. 2009, 49, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Jing, J.; Guo, H. The role of trust with car-sharing services in the sharing economy in China: From the consumers’ perspective. In International Conference on Cross-Cultural Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 634–646. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, T.H. How expected benefit and trust influence knowledge sharing. Industr. Manag. Data Syst. 2013, 113, 506–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, L.C.; Cross, R.; Lesser, E.; Levin, D.Z. Nurturing interpersonal trust in knowledge-sharing networks. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2003, 17, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhigg, C. The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business; Random House: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, B.; Botha, E.; Robertson, J.; Kemper, J.A.; Dolan, R.; Kietzmann, J. How to grow the sharing economy? Create Prosumers! Australas. Mark. 2020, 28, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JAndreoni, J.; Rao, J.M. The power of asking: How communication affects selfishness, empathy, and altruism. J. Publ. Econ. 2011, 95, 513–520. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassanelli, C.; Urbinati, A.; Rosa, P.; Chiaroni, D.; Terzi, S. Addressing circular economy through design for X approaches: A systematic literature review. Comput. Ind. 2020, 120, 103245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassanelli, C.; Pezzotta, G.; Pirola, F.; Terzi, S.; Rossi, M. Design for Product Service Supportability (DfPSS) approach: A state of the art to foster Product Service System (PSS) design. Procedia CIRP 2016, 47, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. The free-energy principle: A rough guide to the brain? Trend Cogn. Sci. 2009, 13, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friston, K.; Kilner, J.; Harrison, L. A free energy principle for the brain. J. Physiol.-Paris 2006, 100, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffily, M.; Coricelli, G. Emotional valence and the free-energy principle. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013, 9, e1003094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagisawa, H.; Kawamata, O.; Ueda, K. Modeling emotions associated with novelty at variable uncertainty levels: A bayesian approach. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.; Frith, C. A duet for one. Conscious Cogn. 2015, 36, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Varshney, L.R.; Nagayama, S.; Kazama, M.; Kitagawa, T.; Ishikawa, Y. A computational neuroscience perspective on subjective wellbeing within the active inference framework. Int. J. Wellbeing 2022, 12, 102–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ho, M.-X.; Yanagisawa, H. Design for Well-Being and Sustainability: A Conceptual Framework of the Peer-to-Peer Sharing and Reuse Platform in the Circular Economy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8852. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118852

Ho M-X, Yanagisawa H. Design for Well-Being and Sustainability: A Conceptual Framework of the Peer-to-Peer Sharing and Reuse Platform in the Circular Economy. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8852. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118852

Chicago/Turabian StyleHo, Meng-Xun, and Hideyoshi Yanagisawa. 2023. "Design for Well-Being and Sustainability: A Conceptual Framework of the Peer-to-Peer Sharing and Reuse Platform in the Circular Economy" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8852. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118852

APA StyleHo, M.-X., & Yanagisawa, H. (2023). Design for Well-Being and Sustainability: A Conceptual Framework of the Peer-to-Peer Sharing and Reuse Platform in the Circular Economy. Sustainability, 15(11), 8852. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118852