Vehicle Aerodynamic Noise: A Systematic Review of Mechanisms, Simulation Methods, and Bio-Inspired Mitigation Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

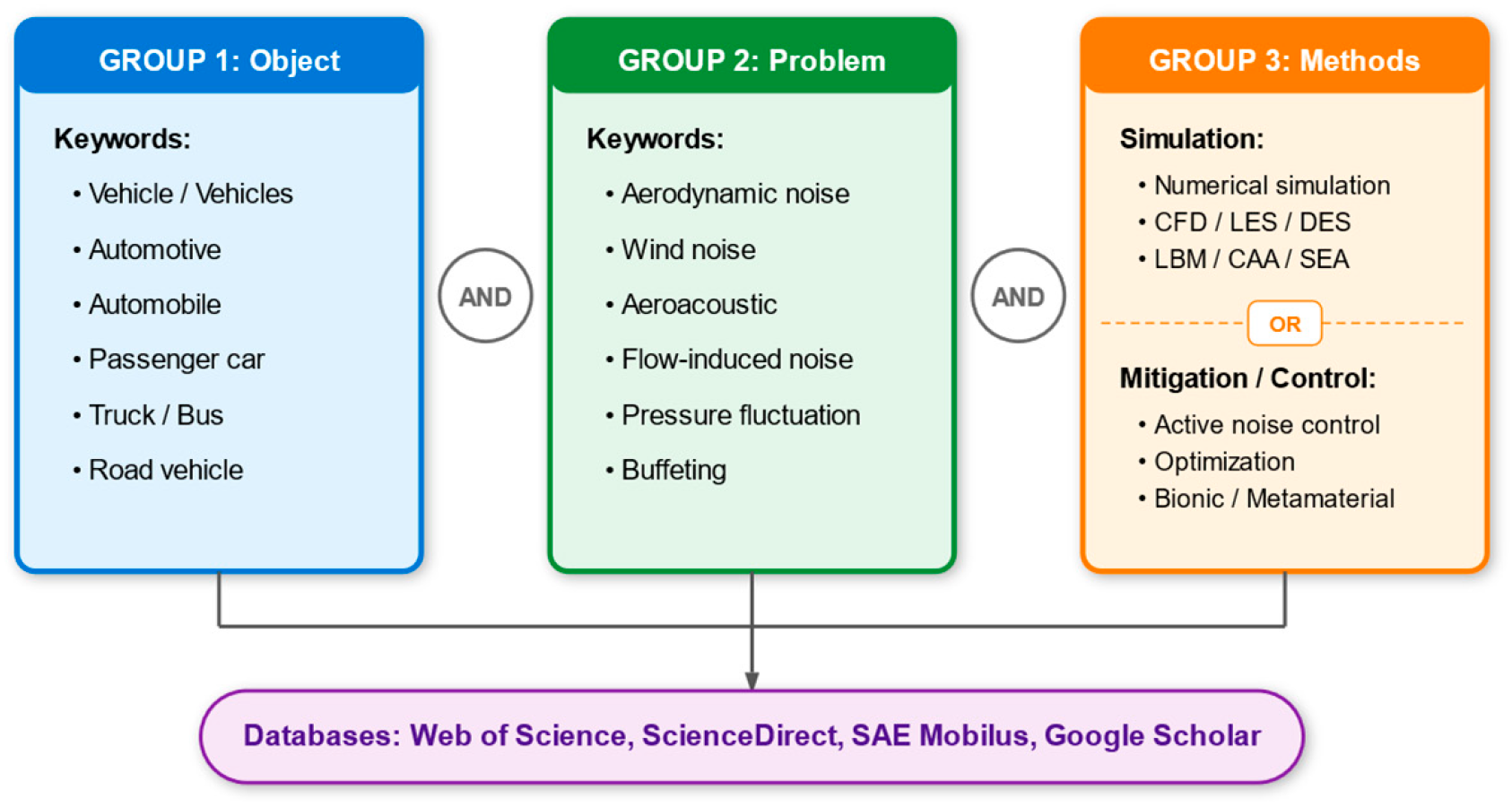

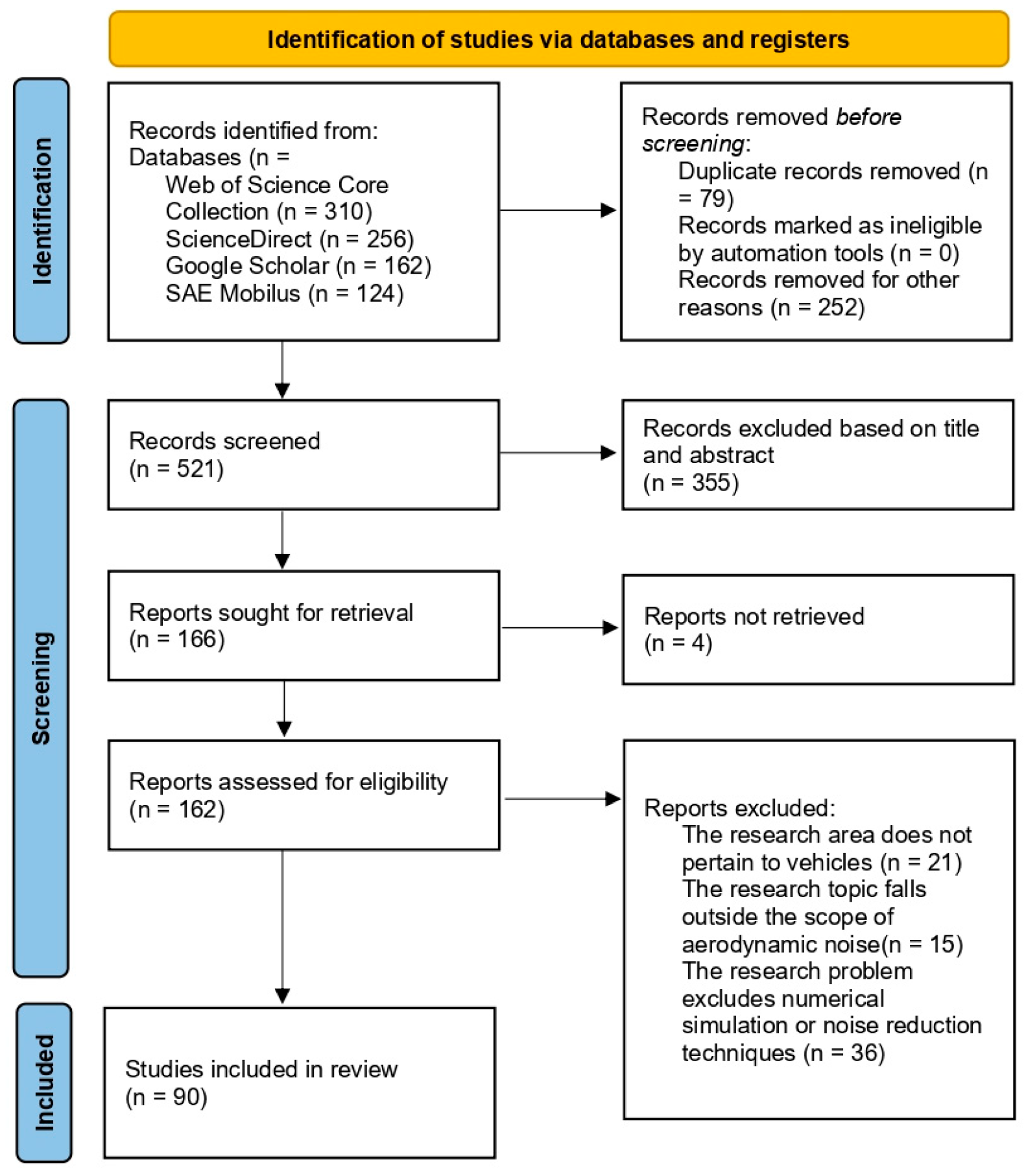

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Configure Exclusion and Inclusion Criteria

3. Results and Discussion

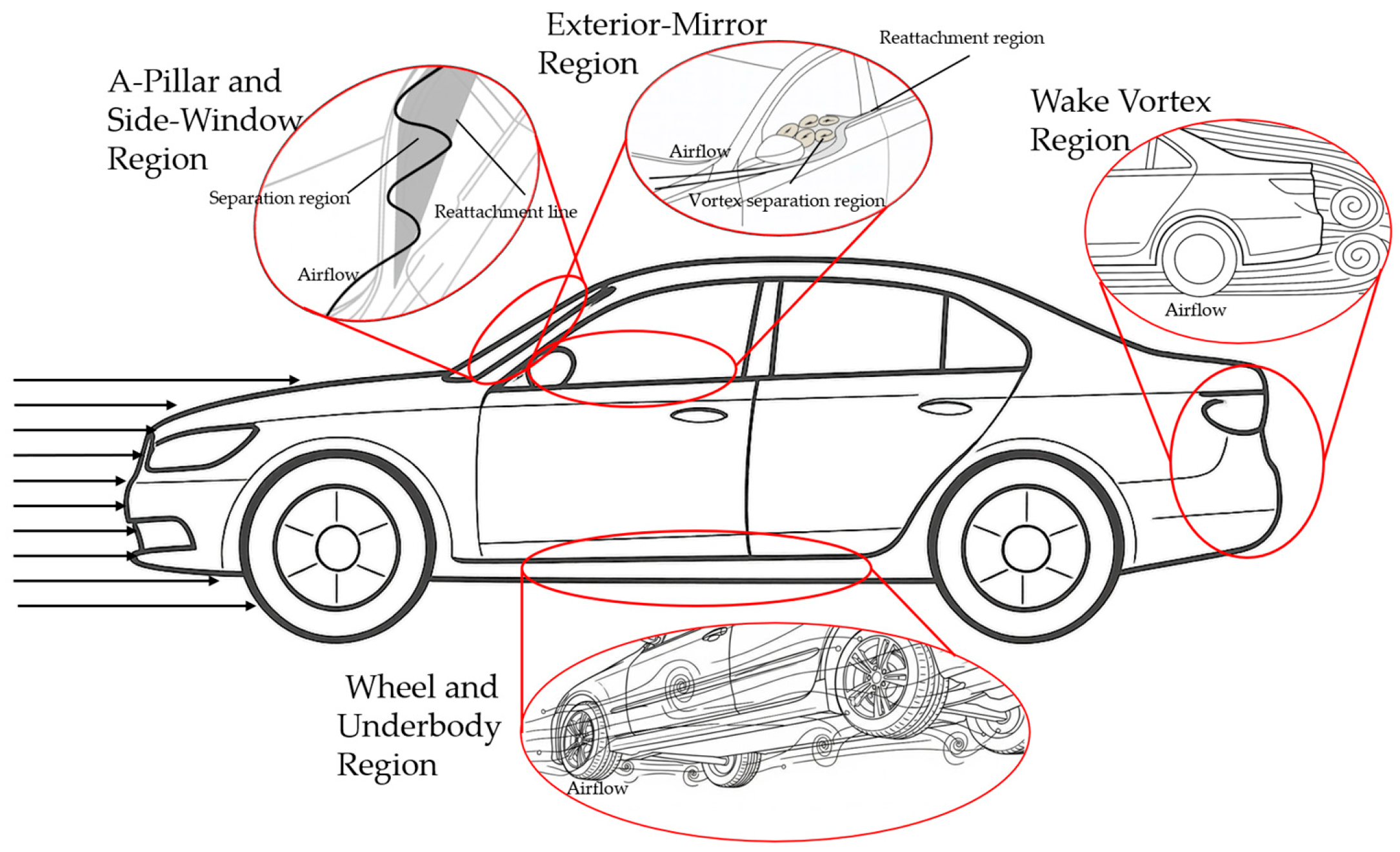

3.1. Generation Mechanisms and Characterization of Aerodynamic Noise

3.1.1. Mechanisms and Classification of Aerodynamic Noise

3.1.2. Typical Aerodynamic Noise Source Regions and Influencing Factors

A-Pillar and Side-Window Region

Exterior-Mirror Region

Wheel and Underbody Region

Wake Vortex Region

Other Noise Sources

3.1.3. Evaluation Metrics and Objective–Subjective Characterization of Aerodynamic Noise

3.2. Numerical Simulation Techniques for Aerodynamic Noise

3.2.1. Flow-Field Simulation Technology

Mainstream Turbulence Models

Numerical Discretization and Boundary Treatment

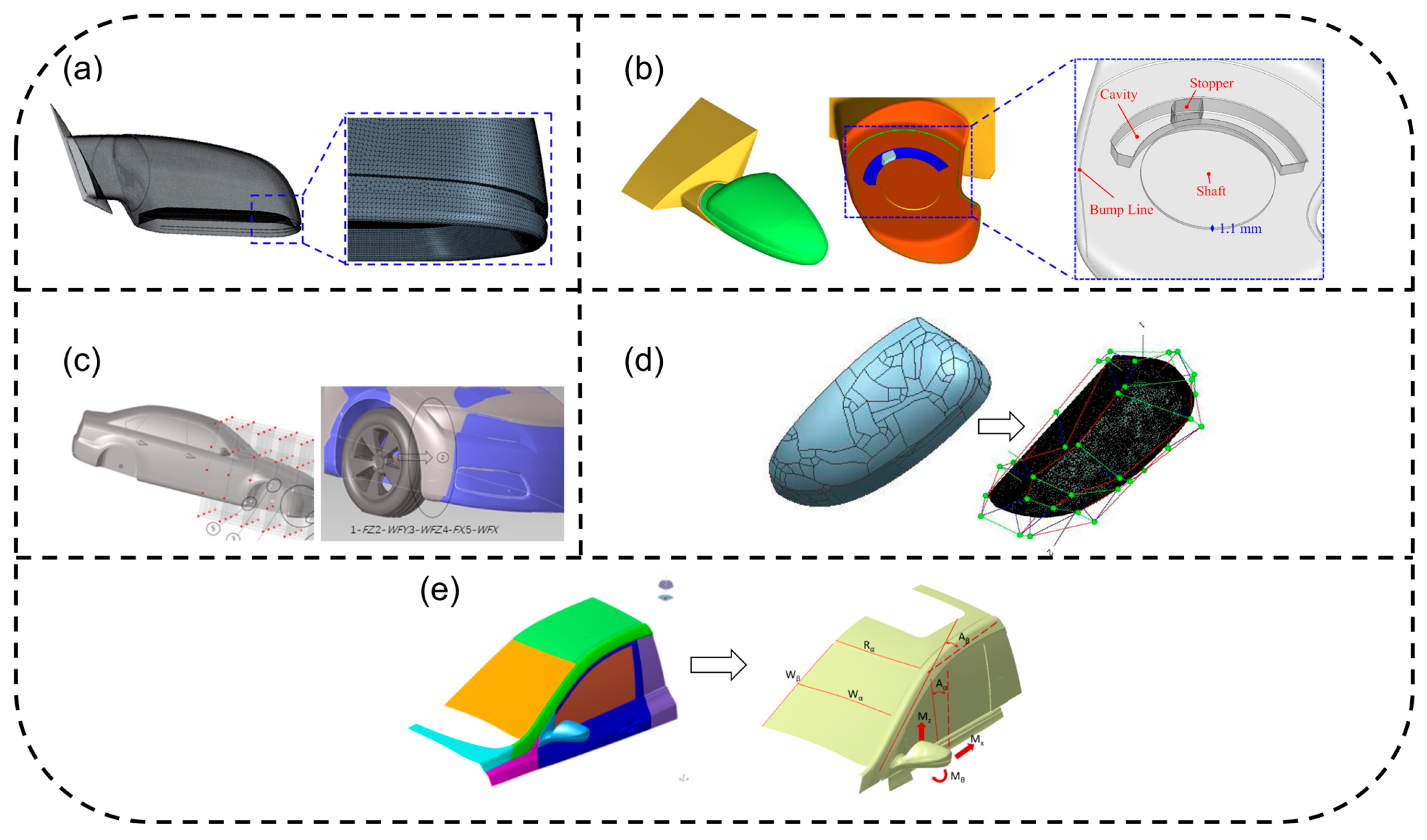

Mesh Strategy and Computational Optimization

3.2.2. Acoustic Simulation Techniques

Mainstream Numerical Simulation Methods

Source Identification and Localization Techniques

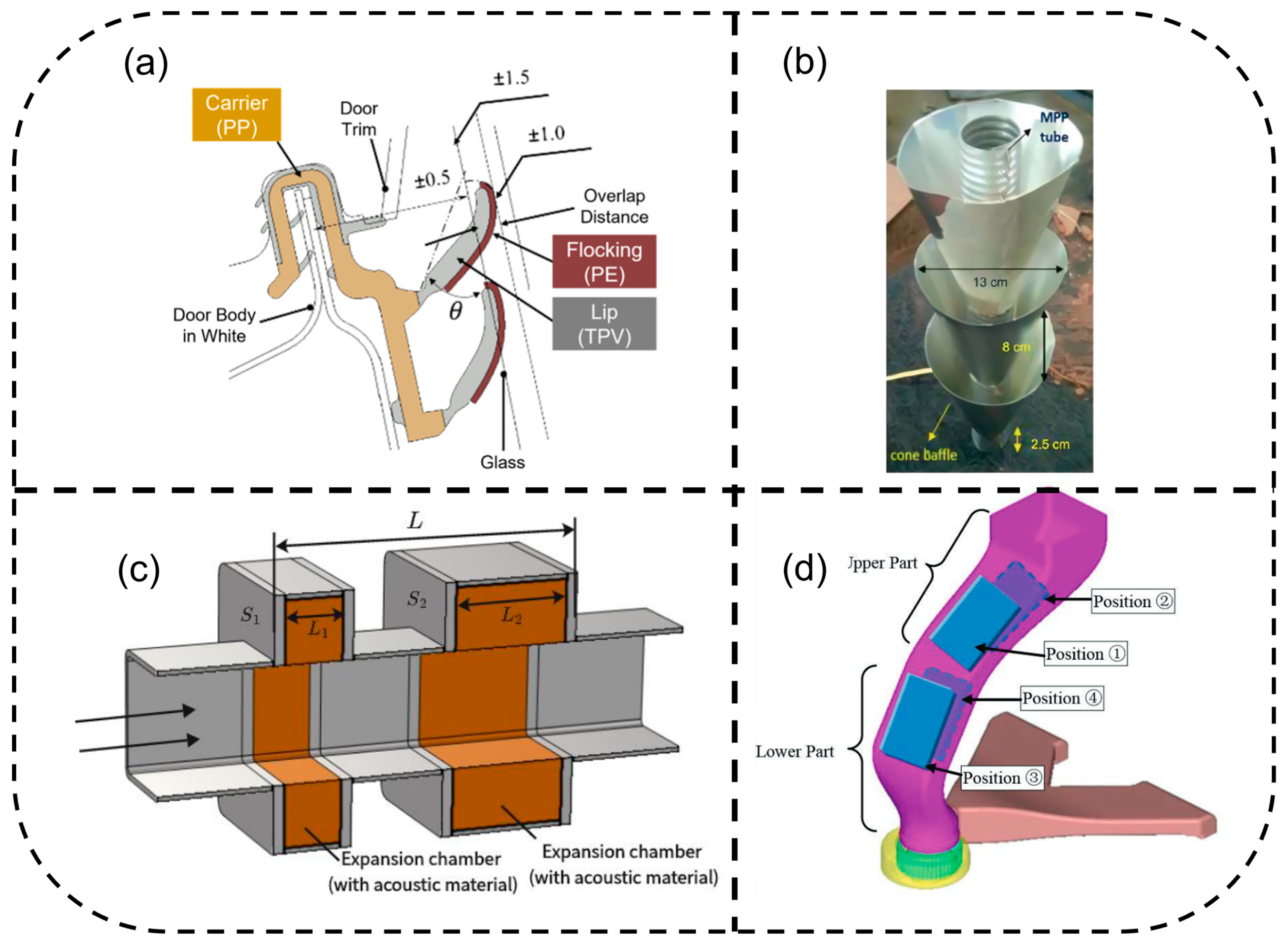

Acoustic-Transmission Modeling of Sealing Systems

3.2.3. Validation and Uncertainty Analysis of Numerical Simulations

Choice of Computational Models and Algorithms

Mesh Resolution and Boundary Conditions

Experiment–Simulation Matching Error

3.3. Advanced Control Techniques for Aerodynamic Noise

3.3.1. Passive Control Technology

Shape-Optimization Design

Application of Sound Absorption and Damping Materials

3.3.2. Active Noise Control Technology

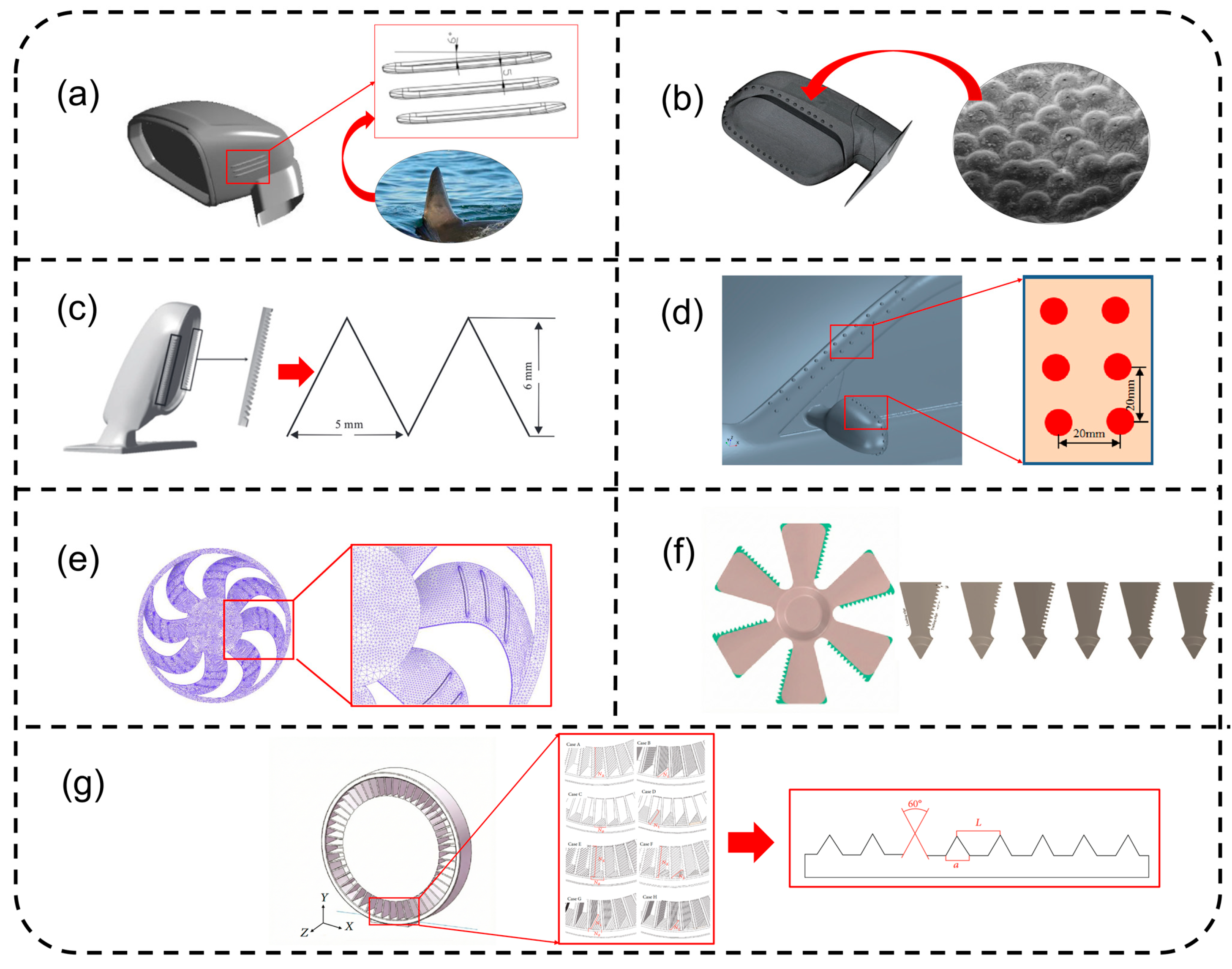

3.3.3. Bio-Inspired Design

3.4. Design Methodologies and Optimization Strategies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANC | Active Noise Control |

| APE | Acoustic Perturbation Equation |

| ATPA | Acoustic Transfer Path Analysis |

| BEM | Boundary Element Method |

| CAA | Computational Aeroacoustics |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| DES | Detached Eddy Simulation |

| DDES | Delayed Detached Eddy Simulation |

| DNC | Direct Numerical Computation |

| FFD | Free-Form Deformation |

| FW-H | Ffowcs Williams–Hawkings |

| HAANC | Hybrid Aerodynamic Active Noise Control |

| HHT | Hilbert–Huang Transform |

| ICA | Independent Component Analysis |

| IDDES | Improved Delayed Detached Eddy Simulation |

| LAA | Lighthill Acoustic Analogy |

| LBM | Lattice Boltzmann Method |

| LES | Large Eddy Simulation |

| LHS | Latin Hypercube Sampling |

| MPPs | Microperforated Panels |

| NPT | Non-Pneumatic Tire |

| NTF | Noise Transfer Function |

| NVH | Noise, Vibration, and Harshness |

| PU | Polyurethane Foam |

| RANS | Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| SBES | Stress-Blended Eddy Simulation |

| SEA | Statistical Energy Analysis |

| SPL | Sound Pressure Level |

| TL | Transmission Loss |

| TPV | Thermoplastic Vulcanizate |

| URANS | Unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes |

| VMD | Variational Mode Decomposition |

| y+ | Dimensionless Wall Distance |

Appendix A

| Study | Bionic Prototype | Application | Key Mechanism | Method | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ye et al. (2021) [106] | Shark dorsal fin | Mirror surface | Reduces negative pressure and TKE | Hybrid CAA | 7.3 dB reduction |

| Wan and Ma (2017) [90] | Beetle head bumps | Mirror housing | Suppresses vortex pair formation | CFD and Tunnel | 10 dB reduction |

| Chen et al. (2018) [107] | Bionic serrations | Mirror edges | Weakens vortex sound coupling | Exp. and CFD | 500 Hz or higher suppression |

| Liu et al. (2018) [108] | Shell ribs | A-pillar and window | Reorganizes horseshoe vortices | Transient CFD | 20 dB reduction |

| Wang et al. (2021) [47] | Ribbed surface | Cooling fan blades | Delays transition and minimizes secondary vortices | Exp. and Orthogonal | 3.83 dB(A) reduction |

| Hur et al. (2023) [45] | Owl wing serrations | Cooling fans | Disrupts trailing edge coherence | LES and LAA | 10 dB reduction |

| Zhou et al. (2020) [36] | Shark skin riblets | Non-pneumatic tire | Fragments vortices and reduces strain energy | LES | 5.18 dB reduction |

| Study | Region | Primary Mechanism | Methodology | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hu et al. (2021) [27] | Side Window | Helmholtz resonance and vortex shedding | CFD and CAA | Deflectors reduce buffeting by disrupting vortex paths |

| Ali et al. (2018) [28] | A-pillar and Mirror | Conical vortex formation and wake interaction | CFD (DriAver) | Mirror turbulence dominates high frequency noise |

| Lee et al. (2022) [34] | Mirror Gap | Acoustic feedback loop and gap flow instability | Compressible LES | Gap geometry triggers narrow band tonal whistling |

| Chode et al. (2023) [40] | Mirror and Wake | Horseshoe and A-pillar vortex interference | Hybrid CAA | 16 degree tilt reduces noise by 10 dB |

| Uhl et al. (2023) [68] | Mirror Region | Turbulent wall pressure fluctuations | CAA and Stochastic | Efficiently predicts broadband noise |

| Li et al. (2018) [94] | Mirror and A-pillar | Interaction between wake and separation flow | GA and CFD | Optimization reduces driver ear noise by 2.08 dB(A) |

| Study | Research Object | Core Methodology | Physical Model | Key Metrics | Main Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. (2024) [58] | Passenger Vehicle | Error Source Analysis | Standardized CFD simulation strategy | ||

| Guo et al. (2022) [109] | FCV Cooling Fan | RSM and Box–Behnken | LES and FW-H Analogy | SPL and Flow Rate | Aeroacoustic optimization of FCV fans |

| Hamiga et al. (2020) [79] | Ahmed Body (25°) | CFD-CAA Coupling | SST and LES | Drag and Flow Topology | Baseline model for moving vehicle noise |

| Hua et al. (2021) [52] | BEV NVH | Systematic Review | BEM and FEM | Tonal Noise | Defined NVH challenges in engine-less EVs |

| Kato et al. (2016) [104] | Micro-EV Window | Active Noise Control | Magnetostrictive Model | Vibration and dB | Structural excitation for road noise control |

| Beigmoradi et al. (2021) [39] | Hatchback Rear | Fractional Factorial | and Acoustic Power | Multi-objective geometry optimization | |

| Cavaliere et al. (2023) [11] | BiW Structure | ROM and PGD Algorithm | Parametric FEA | Modal and Stiffness | Real-time NVH visualization and solver |

| Li et al. (2017) [83] | Intake System | LES-FEM Coupling | and LES | Transmission Loss | Validated LES-FEM for duct acoustics |

| Ma et al. (2025) [6] | Cabin Wind Noise | WOA-Xception (AI) | Shape-Feature CNN | Loudness and MAE | Rapid prediction based on body shape |

| Moron et al. (2023) [72] | On-Road Turbulence | CFD-SEA Hybrid | LBM (VLES) | Modulation Noise | Real-world vs. wind tunnel discrepancies |

| Münder et al. (2022) [2] | EV Soundscape | Perceptual Analysis | Psychoacoustic Metrics | Annoyance and Sharpness | Perceptual standard for BEV evaluation |

| Kato et al. (2018) [105] | Micro-EV Cabin | Small Actuator ANC | Feedback Control | Noise Gain (dB) | Compact ANC for space-limited EVs |

| Li et al. (2022) [96] | SUV Full-Scale | APE-SEA Method | AI and SPL | High-frequency wind noise optimization | |

| Oettle et al. (2019) [78] | Door and Window Seals | LBM-SEA Hybrid | Transmission Loss | Interior SPL | Seal performance prediction in early design |

| Oettle et al. (2017) [1] | Automotive CAA | Technology Overview | Source-Path Receiver | Drag and Aero-Noise | Evolution of aeroacoustic design trends |

| Padavala et al. (2021) [99] | Pure BEV | EMA and Masking Tests | Experimental Modal | Order Tracking | Identified electric powertrain tonal issues |

| Qian et al. (2021) [12] | EV Sound Quality | SA-GA-BPNN (AI) | Objective–Subjective Map | Psychoacoustic Index | Intelligent evaluation of BEV sound quality |

| Wen et al. (2025) [3] | Cabin Voice | Transformer-based AI | Time–Frequency Hybrid | SNR and Signal Loss | Wideband noise reduction and voice recovery |

| Yao et al. (2019) [74] | Glass Window | LES-Vibro-Acoustics | Fluid–Structure (FSI) | Wavenumber-Freq | Characterized turbulence-induced vibration |

| Zhan et al. (2021) [13] | Poroelastic Media | Freq-Domain SEM | Anisotropic Media | Wave Attenuation | Efficient modeling for cabin trim materials |

| Zhang et al. (2025) [5] | SUV Full-Scale | SEA | Leakage and Path | Articulation Index | Quantified seal impact on cabin wind noise |

| Study | Research Object | Key Findings (Quantitative/Qualitative) |

|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. (2021) [4] | Vehicle Body | Qualitative: Wind noise contribution increases with speed; difficult to control side window buffeting passively |

| Horváth et al. (2024) [7] | Electric Vehicle Powertrain | Qualitative: System-level approach required for NVH management in EVs |

| Deng et al. (2023) [8] | Electric Vehicle Chassis | Qualitative: Battery pack affects flow/pressure fields; drag/lift coefficients increase |

| He et al. (2020) [25] | DrivAer Side Glass | Qualitative: Acoustic pressure fluctuations have higher transmission efficiency than convective; acoustic fraction dominates above coincidence frequency |

| Hou et al. (2021) [26] | Vehicle Wind Tunnel | Qualitative: Observations from wind tunnel measurements for wind noise development |

| Azman et al. (2024) [29] | Vehicle Side Mirror | Quantitative: Horizontal base produces 103.41 dB at 120 km/h; Angular base produces 101.48 dB at 120 km/h |

| Hao et al. (2022) [30] | Electric Vehicle Rearview Mirror | Qualitative: Electric vehicle shows less turbulent pressure and sound pressure levels |

| Jamaludin et al. (2023) [31] | Automotive Side Mirror | Quantitative: Sedan mirror produces 77.21 dB at 120 km/h; SUV mirror produces 75.71 dB at 120 km/h |

| Zaareer et al. (2022) [32] | Vehicle Side Mirror | Qualitative: Horizontal base generates noticeably higher noise than angular placement |

| Yuan et al. (2017) [33] | Rear View Mirror | Qualitative: Flow field around mirror is 3D, unsteady, separated, and turbulent |

| Dinh et al. (2022) [35] | Car Side Mirror | Qualitative: Analyzes turbulent flow structure and predicts external acoustic field |

| Yang et al. (2024) [37] | Electric Vehicle Underbody | Qualitative: Underbody airflow increasingly affects interior noise; evaluated side skirts and wind deflectors |

| Wang et al. (2021) [38] | Vehicle Underbody | Qualitative: Underbody contributes mainly to low/middle frequencies; investigated panel thickness effects |

| Saf et al. (2020) [41] | Vehicle Door Seals | Qualitative: STL affected by material, cross-section design, and system dynamics |

| Sun et al. (2022) [42] | Centrifugal Air Compressor | Quantitative: Noise reduced by 4.1 dBA (structure); 5.8 dBA (muffler); total reduction from 78.8 to 68.9 dBA |

| Hua et al. (2017) [43] | Automobile Alternator | Quantitative: Average noise level decreased by 2.58 dB; mass flow increased by 1.36 g/s |

| Miyamoto et al. (2017) [44] | Automobile Bonnet | Qualitative: Tonal noise effectively reduced; separation around kink suppressed by PA control |

| Ren et al. (2023) [46] | Automotive Cooling Fan | Qualitative: Main noise at tip of forward swept wing; SPL metrics analyzed |

| He et al. (2021) [48] | DrivAer Side Window | Qualitative: Hydrodynamic pressure loses more energy than acoustic; side window acts as low-wavenumber filter |

| Fukushima et al. (2016) [49] | Vehicle Body | Qualitative: New transmission model treats sources as forces; quantitative synthesis of interior noise |

| Carr et al. (2021) [50] | Vehicle Interior | Qualitative: Models improved by including sharpness metric with loudness |

| Carr et al. (2022) [51] | Vehicle Interior | Qualitative: Gusting metric needed for non-stationary wind noise acceptability |

| He et al. (2018) [53] | DrivAer Front Side Window | Qualitative: Good agreement of up to 1000 Hz between calculated and measured radiation |

| Talay et al. (2019) [55] | Vehicle Door | Qualitative: Door stiffness and sealing gap affect interior wind noise at high speeds |

| Yin et al. (2019) [56] | Automobile Side Window | Qualitative: SPL and loudness increase with velocity; sharpness decreases with window opening degree |

| Yadegari et al. (2020) [57] | Multiple: Side mirrors, A-pillars, Vehicle body | Qualitative: Reviewed noise reduction techniques across aerospace, turbomachinery, and automotive industries |

| Masri et al. (2024) [59] | Electric/Hybrid Vehicle | Qualitative: NVH sources shift from powertrain (ICE) to road-tire and wind-structure interactions at high speeds |

| Zhu et al. (2017) [62] | High-speed Train | Qualitative: Main noise from leading bogie; inter-carriage gap causes tonal noise; peak A-weighted SPL at ~1 kHz |

| Li et al. (2019) [64] | Computational Aeroacoustics | Qualitative: LBM shows superior space–time resolution for direct/indirect noise computations |

| Duan (2020) [66] | SUV Rear-view Mirror | Quantitative: Interior SPL reduced by 6.41%; speech intelligibility improved by 33.89% |

| Guseva et al. (2022) [67] | Generic Side Mirror | Qualitative: Validated hybrid simulation method; good agreement with experimental data |

| Ali et al. (2018) [69] | Generic Vehicle | Qualitative: Good SPL agreement (200-2000 Hz) between calculation and experiment |

| Zhong et al. (2019) [70] | Passenger Vehicle | Qualitative: Major sources: underbody (<200 Hz), windows (>200 Hz); 260 M cells give better accuracy |

| Dawi et al. (2019) [71] | Generic Vehicle Model | Qualitative: Demonstrated direct noise computation; compared with/without side mirror |

| Liang et al. (2020) [75] | Harvester vehicles | Qualitative: Flow field homogenization and vortex reconstruction |

| Liang et al. (2020) [73] | Rice Combine Harvester Fan | Quantitative: Requested airflow 3.0 m3/s; upper duct 8–9 m/s; middle section 4–6 m/s; tail section 3–4 m/s |

| Tajima et al. (2024) [76] | Vehicle in Wind Conditions | Qualitative: Fluctuating wind noise is amplitude-modulated aerodynamic noise; MPS analysis enables quantitative evaluation |

| Ding et al. (2022) [77] | Rice Combine Harvester | Qualitative: Grain sieve losses and impurity ratio improved dramatically with multi-duct cleaning |

| Xu et al. (2020) [80] | Rice Combine Harvester | Quantitative: Prediction error < 9.4% for cleaning loss ratio; < 11.7% for grain impurity ratio |

| Deng et al. (2018) [82] | Automotive Door Sealing | Qualitative: TL optimization using orthogonal design based on articulation index |

| Wang et al. (2017) [84] | Vehicle Rear Window | Quantitative: SPL calculation error <2%; Both sides open much quieter than single window |

| Tang et al. (2017) [85] | Rotating Drive Component | Qualitative: Unsteady fluid impact loading and surface stress distribution optimization |

| Broatch et al. (2016) [86] | Automotive Turbocharger | Qualitative: Noise increases toward surge; high-frequency stall oscillations; whoosh noise from rotating cells |

| Fordjour et al. (2020) [87] | Rotating Drive Component | Qualitative: Enhanced acoustic stability via precise rotational |

| Mo et al. (2020) [88] | Automotive Cooling Fan | Quantitative: Tonal noise 110 dB SPL at blade tip; 5–6 dB decay per distance doubling |

| Hu et al. (2021) [89] | Vehicle Thermal Management Fan | Qualitative: Significant suppression of turbulent kinetic energy and flow-induced acoustic sources. |

| Zhu et al. (2018) [91] | Rear View Mirror | Quantitative: Maximum noise decrease rate 15.62%; minimum 8.90% |

| Jiao et al. (2024) [92] | Passenger Car Fender | Qualitative: Fender shape optimization reduces aerodynamic noise; investigated flow field characteristics |

| Rao et al. (2018) [93] | Rearview Mirror | Quantitative: Maximum noise reduction amplitude up to 3 dB after optimization |

| Rao et al. (2017) [95] | SUV Rearview Mirror | Qualitative: Analyzed flow field and noise characteristics behind mirror using reconstructed 3D model |

| Lee et al. (2023) [98] | EV Door Weatherstrip | Quantitative: Wind noise reduced 5 dB(A); friction coefficient reduced 80% |

| Hu et al. (2024) [100] | Rearview Mirror and Side Window | Qualitative: Mirror body proportion, lower edge angle, column length affect noise in order |

| Huang et al. (2024) [101] | Electric Vehicle AC System | Qualitative: Addressed non-planar wave cavity resonance in EV air conditioning noise |

| Cao et al. (2018) [102] | HEV Battery Cooling | Qualitative: Cap structure modified noise directionality; fan speed optimized based on masking |

| Shen et al. (2024) [103] | Combine Harvester | Quantitative: Detection error 6.1% between detected and actual loss amounts |

| Liang et al. (2022) [109] | Harvester vehicles | Qualitative: Flow field consistency and noise source suppression achieved through dual fan cooperation |

References

- Oettle, N.; Sims-Williams, D. Automotive Aeroacoustics: An Overview. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. D-J. Automob. Eng. 2017, 231, 1177–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münder, M.; Carbon, C.-C. A Literature Review [2000–2022] on Vehicle Acoustics: Investigations on Perceptual Parameters of Interior Soundscapes in Electrified Vehicles. Front. Mech. Eng. 2022, 8, 974464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Deng, F.; Su, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Addressing Aerodynamic Noise in Vehicles: A Hybrid Method for Noise Reduction and Signal Preservation. Appl. Acoust. 2025, 236, 110747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y. An Overview of Automotive Wind Noise and Buffeting Active Control. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2021, 5, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, T.; Wang, Y.; Niu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, C.; Zhang, C. Research on the Influence of Door and Window Sealing on Interior Wind Noise Based on Statistical Energy Analysis. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2025, 9, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yi, H.; Ma, L.; Deng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Peng, Y. Prediction of Vehicle Interior Wind Noise Based on Shape Features Using the WOA-Xception Model. Machines 2025, 13, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, K.; Zelei, A. Simulating Noise, Vibration, and Harshness Advances in Electric Vehicle Powertrains: Strategies and Challenges. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Lu, K.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Shen, H.; Gong, J. Numerical Simulation of Aerodynamic Characteristics of Electric Vehicles with Battery Packs Mounted on Chassis. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Tian, F.-B. Sound Generated by the Flow around an Airfoil with an Attached Flap: From Passive Fluid–Structure Interaction to Active Control. J. Fluids Struct. 2022, 111, 103571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.K.; Zekry, D.A.; Saro-Cortes, V.; Lee, K.J.; Wissa, A.A. Aerial and Aquatic Biological and Bioinspired Flow Control Strategies. Commun. Eng. 2023, 2, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, F.; Zlotnik, S.; Sevilla, R.; Larrayoz, X.; Díez, P. Nonintrusive Parametric NVH Study of a Vehicle Body Structure. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 2023, 51, 6557–6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Hou, Z. Intelligent Evaluation of the Interior Sound Quality of Electric Vehicles. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 173, 107684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.; Zhuang, M.; Liu, Q.Q.; Shi, L.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Q.H. Frequency Domain Spectral Element Method for Modelling Poro-elastic Waves in 3-D Anisotropic, Heterogeneous and Attenuative Porous Media. Geophys. J. Int. 2021, 227, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Kockelman, K.M.; Lee, J. Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Long-Distance Business Travel: How Far Can We Go? Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2676, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J. Qiche Cheshen Zaosheng yu Zhendong Kongzhi; China Machine Press: Beijing, China, 2015; ISBN 978-7-111-49107-1. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Oettle, N.; Sims-Williams, D.; Dominy, R. Assessing the Aeroacoustic Response of a Vehicle to Transient Flow Conditions from the Perspective of a Vehicle Occupant. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars—Mech. Syst. 2014, 7, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, I.R.; Kendrick, P.; Cox, T.J.; Fazenda, B.M.; Li, F. Perceptual Evaluation of the Functional and Aesthetic Degradation of Speech by Wind Noise during Recording. Proc. Mtgs. Acoust. 2013, 19, 060170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Bren-nan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Re-views. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lighthill, M.J.; Newman, M.H.A. On Sound Generated Aerodynamically I. General Theory. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1952, 211, 564–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curle, N.; Lighthill, M.J. The Influence of Solid Boundaries upon Aerodynamic Sound. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1955, 231, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ffowcs Williams, J.E.; Hawkings, D.L.; Lighthill, M.J. Sound Generation by Turbulence and Surfaces in Arbitrary Motion. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1969, 264, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.R.; Callister, J.R. Aerodynamic Noise of Ground Vehicles; SAE Technical Paper 911027; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.R. Automobile Aerodynamic Noise. SAE Trans. 1990, 99, 434–457. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44553993 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- He, Y.; Schröder, S.; Shi, Z.; Blumrich, R.; Yang, Z.; Wiedemann, J. Wind Noise Source Filtering and Transmission Study through a Side Glass of DrivAer Model. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 160, 107161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H. Wind Noise Contribution Analysis. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars–Mech. Syst. 2021, 14, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Guo, P.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, J.; Sun, X.; Sang, T.; Lan, W.; Wang, J. Buffeting Noise Characteristics and Control of Auto-mobile Side Window. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2021, 5, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.S.M.; Jalasabri, J.; Sood, A.M.; Mansor, S.; Shaharuddin, H.; Muhamad, S. Wind Noise from A-Pillar and Side View Mirror of a Realistic Generic Car Model, DriAver. Int. J. Veh. Noise Vib. 2018, 14, 38–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, A.K.I.; Mahmudin, R. Study on Effect of Vehicle Side Mirror Base Position on Noise. Prog. Eng. Appl. Technol. 2024, 5, 303–309. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, Q. Study on Flow Field and Aerodynamic Noise of Electric Vehicle Rearview Mirror. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. D J. Automob. Eng. 2022, 236, 724–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaludin, N.M.J.; Sapit, A.; Baharuddin, M.A.; Nakagiri, M. Aerodynamic Analysis on Noise from Automotive Side Mirror Using CFD. J. Emerg. Technol. Ind. Appl. 2023, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaareer, M.; Mourad, A.-H. Effect of Vehicle Side Mirror Base Position on Aerodynamic Forces and Acoustics. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 1437–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, Q. Effects of Installation Environment on Flow around Rear View Mirror. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars Mech. Syst. 2017, 10, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Cheong, C. Numerical Investigation of Whistling Sound in Narrow-Gap Flow of Automobile Side Mirror. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 197, 108893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, C.-T. Aerdynamic Noise Simulation of a Car Side Mirror at Hight Speed. JST Eng. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 32, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhai, H.; Wang, G. Numerical Investigation of Aerodynamic Noise Reduction of Nonpneumatic Tire Using Nonsmooth Riblet Surface. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2020, 4345723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Sun, Z.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Y. Numerical Investigation on the Characteristics of Underbody Aerodynamic Noise Sources in Electric Vehicles. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2756, 12012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, M.; Su, C.; Wu, W. Numerical Investigation on the Contribution of Underbody Flow-Induced Noise on Vehi-cle Interior Noise. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. D-J. Automob. Eng. 2021, 235, 2667–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigmoradi, S.; Vahdati, M. Multi-Objective Optimization of a Hatchback Rear End Utilizing Fractional Factorial Design Algorithm. Eng. Comput. 2021, 37, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chode, K.; Viswanathan, H.; Chow, K.; Reese, H. Investigating the Aerodynamic Drag and Noise Characteristics of a Stand-ard Squareback Vehicle with Inclined Side-View Mirror Configurations Using a Hybrid Computational Aeroacoustics (CAA) Approach. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 75148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saf, O.; Erol, H.; Kutlu, A.E. An Investigation of the Sound Transmission Loss for Elastomeric Vehicle Door Seals. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 165, 107296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Xing, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhou, M.; Wang, C.; Cui, H. Study on Characteristics and Control of Aerodynamic Noise of a High-Speed Centrifugal Air Compressor for Vehicle Fuel Cells. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, D.; Yan, B.; Ouyang, H. Aerodynamic Noise Numerical Simulation and Noise Reduction Study on Automobile Alternator. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2017, 31, 2047–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, T.; Yokoyama, H.; Iida, A. Suppression of Aerodynamic Tonal Noise from an Automobile Bonnet Using a Plas-ma Actuator. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars-Mech. Syst. 2017, 10, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, K.; Haider, B.; Sohn, C. Trailing Edge Serrations for Noise Control in Axial-Flow Automotive Cooling Fans. Int. J. Aeroacoustics 2023, 22, 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Deng, C.; Sun, H. Flow Field Analysis and Noise Characteristics of an Automotive Cooling Fan at Different Speeds. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1259052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, X.; Shen, L.; Yang, A.; Chen, E.; Fieldhouse, J.; Barton, D.; Kosarieh, S. Noise Reduction of Automobile Cooling Fan Based on Bio-Inspired Design. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. D J. Automob. Eng. 2021, 235, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wan, R.; Liu, Y.; Wen, S.; Yang, Z. Transmission Characteristics and Mechanism Study of Hydrodynamic and Acous-tic Pressure through a Side Window of DrivAer Model Based on Modal Analytical Approach. J. Sound Vib. 2021, 501, 116058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, T.; Takagi, H.; Enomoto, T.; Sawada, H.; Kaneda, T. A New Method of Characterizing Wind Noise Sources and Body Response for a Detailed Analysis of the Noise Transmission Mechanism. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars Mech. Syst. 2016, 9, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.; Davies, P. Perception of Stationary Wind Noise in Vehicles. Noise Control Eng. J. 2021, 69, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.; Davies, P. Perception of Non-Stationary Wind Noise in Vehicles. Noise Control Eng. J. 2022, 70, 416–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Thomas, A.; Shultis, K. Recent Progress in Battery Electric Vehicle Noise, Vibration, and Harshness. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 368504211005224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Shi, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Z. Sound Radiation Analysis of a Front Side Window Glass of DrivAer Model under Wind Ex-citation. Shock Vib. 2018, 2018, 5828725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastl, H.; Zwicker, E. Fluctuation Strength. In Psychoacoustics: Facts and Models, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007; pp. 247–256. [Google Scholar]

- Talay, E.; Altinisik, A. The Effect of Door Structural Stiffness and Flexural Components to the Interior Wind Noise at Ele-vated Vehicle Speeds. Appl. Acoust. 2019, 148, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Gu, Z.; Zong, Y.; Zheng, L.; Yang, Z.; Huang, T. Sound Quality Evaluation of Automobile Side-Window Buffeting Noise Based on Large-Eddy Simulation. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control 2019, 38, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadegari, M.; Ommi, F.; Saboohi, Z. Synergy between Noise Reduction Techniques Applied in Different Industries: A Re-view. Int. J. Multiphysics 2020, 14, 161–192. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, J.; Ma, C.; Wu, H.; Li, Z. Research on Precise and Standardized Numerical Simulation Strategy for Vehicle Aerodynamics. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 2024, 34, 1937–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, J.; Amer, M.; Salman, S.; Ismail, M.; Elsisi, M. A Survey of Modern Vehicle Noise, Vibration, and Harshness: A State-of-the-Art. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, J.B. Noise Sources in a Low-Reynolds-Number Turbulent Jet at Mach 0.9. J. Fluid Mech. 2001, 438, 277–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodony, D.J.; Lele, S.K. On Using Large-Eddy Simulation for the Prediction of Noise from Cold and Heated Turbulent Jets. Phys. Fluids 2005, 17, 085103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Hemida, H.; Flynn, D.; Baker, C.; Liang, X.; Zhou, D. Numerical Simulation of the Slipstream and Aeroacoustic Field around a High-Speed Train. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2017, 231, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalino, D. An Advanced Time Approach for Acoustic Analogy Predictions. J. Sound Vib. 2003, 261, 583–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shao, W. Review of Lattice Boltzmann Method Applied to Computational Aeroacoustics. Arch. Acoust. 2019, 44, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B. Cfd Study of Submersible Mixers in Anaerobic Digesters. Trans. ASABE 2017, 60, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Lai, C.; Wang, Y.; Feng, J.; Tan, W. Shu SUV Nei Wa Chang Qidong Zaosheng Shuzi Fenxi. Jichuang Yu Yeya 2020, 48, 78–84. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guseva, E.; Egorov, Y. Application of LES Combined with a Wave Equation for the Simulation of Noise Induced by a Flow Past a Generic Side Mirror. Int. J. Aeroacoustics 2022, 21, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl, P.; Schell, A.; Ewert, R.; Delfs, J. Stochastic Noise Sources for Computational Aeroacoustics of a Vehicle Side Mirror. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Veh. Syst. 2023, 17, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.S.M.; Shaharuddin, N.H.; Jalasabri, J.; Sood, A.M.; Mansor, S. Validation Study on External Wind Noise Prediction Using OpenFOAM. J. Mech. Eng. 2018, 7, 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z. Aerodynamic Noise Prediction of Passenger Vehicle with Hybrid Detached Eddy Sim-ulation/Acoustic Perturbation Equation Method. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. D J. Automob. Eng. 2019, 233, 2390–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawi, A.H.; Akkermans, R.A. Direct Noise Computation of a Generic Vehicle Model Using a Finite Volume Method. Comput. Fluids 2019, 191, 104243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moron, P.; Wu, L.; Powell, R.; Senthooran, S. Numerical Simulation of On-Road Wind Conditions for Interior Wind Noise of Passenger Vehicles. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Pract. Mobil. 2023, 6, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Xu, L.; De Baerdemaeker, J.; Li, Y.; Saeys, W. Optimisation of a Multi-Duct Cleaning Device for Rice Combine Harvesters Utilising CFD and Experiments. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 190, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Davidson, L. Vibro-Acoustics Response of a Simplified Glass Window Excited by the Turbulent Wake of a Quar-ter-Spherocylinder Body. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2019, 145, 3163–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Li, D.; Li, J.; Tian, K. Effects of Fan Volute Structure on Airflow Characteristics in Rice Combine Harvesters. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2020, 18, e0209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, A.; Ikeda, J.; Nakasato, K.; Kamiwaki, T.; Wakamatsu, J.; Oshima, M.; Li, C.; Tsubokura, M. Numerical Simulation of Fluctuating Wind Noise of a Vehicle in Reproduced On-Road Wind Condition. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Pract. Mobil. 2024, 7, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Liang, Z.; Qi, Y.; Ye, Z.; Zhou, J. Improving Cleaning Performance of Rice Combine Harvesters by DEM–CFD Coupling Technology. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oettle, N.; Powell, R.; Senthooran, S.; Moron, P. A Computational Process to Effectively Design Seals for Improved Wind Noise Performance. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Pract. Mobil. 2019, 1, 1690–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamiga, W.; Ciesielka, W. Aeroaocustic Numerical Analysis of the Vehicle Model. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 9066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Chai, X.; Wang, G.; Liang, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, B. Numerical Simulation of Gas-Solid Two-Phase Flow to Predict the Cleaning Performance of Rice Combine Harvesters. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 190, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamuni, M.M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Ravi, S.; Young, J.; Lai, J.C.S.; Tian, F.-B. An Immersed Boundary-Regularized Lattice Boltzmann Method for Modeling Fluid–Structure–Acoustics Interactions Involving Large Deformation. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 113619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Zheng, S.; Wu, X.; Shao, J.; Zhao, M. Optimal Study on the TL of Automotive Door Sealing System Based on the Interior Speech Intelligibility; SAE Technical Paper 2018-01-0672; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hao, Z.; Zheng, X.; Shi, J.; Wang, L. LES-FEM Coupled Analysis and Experimental Research on Aerodynamic Noise of the Vehicle Intake System. Appl. Acoust. 2017, 116, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sui, L.; Yin, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, N.; Guo, H. A Hybrid Prediction for Wind Buffeting Noises of Vehicle Rear Window Based on LES-LAA Method. Appl. Math. Model. 2017, 47, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Li, H.; Issaka, Z.; Chen, C. Impact Forces on the Drive Spoon of a Large Cannon Irrigation Sprinkler: Simple Theory, CFD Numerical Simulation and Validation. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 159, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broatch, A.; Galindo, J.; Navarro, R.; García-Tíscar, J. Numerical and Experimental Analysis of Automotive Turbocharger Compressor Aeroacoustics at Different Operating Conditions. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2016, 61, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordjour, A.; Zhu, X.; Yuan, S.; Dwomoh, F.A.; Issaka, Z. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Study on Internal Flow Characteristic in the Dynamic Fluidic Sprinkler. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2020, 36, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Choi, J. Numerical Investigation of Unsteady Flow and Aerodynamic Noise Characteristics of an Automotive Axial Cooling Fan. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wei, W.; Hu, Z.; Li, P. Optimization Design of Spray Cooling Fan Based on CFD Simulation and Field Experiment for Horticultural Crops. Agriculture 2021, 11, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Ma, L. Numerical Investigation and Experimental Test on Aerodynamic Noises of the Bionic Rear View Mirror in Vehicles. J. Vibroengineering 2017, 19, 4799–4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhu, J.J.; Liu, G.W. Numerical Optimization for Aerodynamic Noises of Rear View Mirrors of Vehicles Based on Rectangular Cavity Structures. J. Vibroeng. 2018, 20, 1240–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, D.; Zhou, H.; Huang, T.; Zhang, W. Numerical Study on Aerodynamic Noise Reduction in Passenger Car with Fender Shape Optimization. Symmetry 2024, 16, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Zhuang, Z. Analysis and Optimization of Aerodynamic Noise in the Rearview Mirror Region. Int. Core J. Eng. 2018, 4, 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Zhong, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Rashidi, M. Multi-Parameter Optimization of Automotive Rear View Mirror Region for Reducing Aerodynamic Noise. Noise Control Eng. J. 2018, 66, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Zhang, D.; Lu, Q. Research on Aerodynamic Noise Simulation of Rearview Mirror Based on Reverse Engineering. Int. Core J. Eng. 2017, 3, 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. Analysis and Optimization of Aerodynamic Noise in Vehicle Based on Acoustic Perturbation Equations and Statistical Energy Analysis. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2022, 6, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, D.; Ma, Z. Simulation on a Car Interior Aerodynamic Noise Control Based on Statistical Energy Analysis. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2012, 25, 1016–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Yoon, B.; Cho, S.; Lee, S.; Hong, K.M.; Suhr, J. Multidisciplinary Design of Door Inner Belt Weatherstrip for Simultaneous Reduction of Wind Noise and Squeaking in Electric Vehicles. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 107567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padavala, P.; Inavolu, N.; Thaveedu, J.R.; Medisetti, J.R. Challenges in Noise Refinement of a Pure Electric Passenger Vehicle. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2021, 5, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Shi, K.; Mao, J.; Guo, P.; Yu, T.; Wang, J. Optimization Study on the Influence of Rearview Mirror and Side Window Glass on Interior Noise. J. Vib. Control 2024, 30, 516–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yan, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Zhan, X. Transmission Loss Characteristics of Dual Cavity Impedance Composite Mufflers for Non-Planar Wave Cavity Resonance. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, D.; He, Y.; Lu, Y.; Mao, J.; Hou, H. Resolution of HEV Battery Cooling System Inlet Noise Issue by Optimizing Duct Design and Fan Speed Control Strategy. SAE Int. J. Engines 2018, 11, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Gao, J.; Jin, Z. Research on Acoustic Signal Identification Mechanism and Denoising Methods of Combine Harvesting Loss. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Suzuki, R.; Narita, T.; Hkato, H.; Yamamoto, Y. Basic Study on Active Noise Control for Considering Characteristics of Vibration of Plate by Giant Magnetostrictive Actuator. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 2016, 52, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Suzuki, R.; Miyao, R.; Kato, H.; Narita, T. A Fundamental Consideration of Active Noise Control System by Small Actuator for Ultra-Compact EV. Actuators 2018, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Xu, M.; Xing, P.; Cheng, Y.; Meng, D.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, M. Investigation of Aerodynamic Noise Reduction of Exterior Side View Mirror Based on Bionic Shark Fin Structure. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 182, 108188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Li, Y.Q.; Ding, Z.Y. Numerical Simulation on the Impact of the Bionic Structure on Aerodynamic Noises of Sidewindow Regions in Vehicles. J. Vibroeng. 2018, 20, 1257–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, H. Experimental and Numerical Investigations of the Aerodynamic Noise Reduction of Automotive Side View Mirrors. J. Hydrodyn. 2018, 30, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Ding, Z.; Su, Z. Cross-Flow Fan on Multi-Dimensional Airflow Field of Air Screen Cleaning System for Rice Grain. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2022, 15, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Mi, T.; Li, L.; Luo, R. Research on Aerodynamic Performance and Noise Reduction of High-Voltage Fans on Fuel Cell Vehicles. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 186, 108454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Time span | 1 January 2016–20 June 2025 | Outside range |

| Document type | Peer-reviewed journal article | Conference paper, thesis, patent, report |

| Content | Numerical aeroacoustic simulation (CFD, LES, CAA, BEM, hybrid) and/or advanced mitigation technology (ANC, plasma actuation, acoustic metamaterials, flow-control devices, shape optimization) | Studies focusing solely on steady-state aerodynamic drag without acoustic pressure analysis; research lacking high-fidelity numerical resolution (e.g., LES, DES, LBM) or specific noise mitigation frameworks |

| Vehicle scope | Road vehicles: passenger cars, trucks, buses | Aircraft, trains, motorcycles, UAVs, eVTOL |

| Source | Ideal Model | Mechanism | Locations | and |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monopole |  | Periodic volumetric pulsation/suction | Door-seal gaps, body joints | |

| Dipole |  | Unsteady wall-pressure forces | A-pillar, exterior mirror, wheel arch | |

| Quadrupole |  | Turbulent shear-stress fluctuations | Wake, underbody shear layers |

| Metric | Symbol/Unit | Domain | Main Aspect Captured | Correlation with Annoyance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-weighted SPL | LAeq (dB A) | Physical | Overall sound-pressure level (baseline reference) | ); alone cannot fully explain discomfort |

| Zwicker loudness | N (sone) | Psycho-acoustic | Perceived volume after auditory weighting | ) |

| Sharpness | S (acum) | Psycho-acoustic | High-frequency spectral balance (“shrillness”) | Adds ≈ 10% explanatory power when combined with loudness |

| Roughness | R (asper) | Psycho-acoustic | Fast (20–300 Hz) amplitude modulation, felt as “harshness” | Small but significant influence in broad-band cases |

| Subjective annoyance score | 1–9 pt jury scale | Subjective | Overall occupant discomfort | Target ≤ 5 pts for acceptable cabin quality |

| Method | Workflow | Pros | Cons | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNS | Solve full comp. Navier–Stokes; sound direct | Highest fidelity | ; huge cost | [60] |

| LES + FW-H | LES field → FW-H radiation | Captures broadband | Fine grid, still costly | [61] |

| DES/DDES + FW-H | RANS/LES mix → FW-H | Good accuracy–cost compromise | Under-resolves very small eddies | [62] |

| URANS + Curle analogy | URANS flow → Curle dipoles | Fast, robust screening of low-frequency tonal noise | Broadband/high-frequency noise poorly captured | [63] |

| LBM | Compressible LBM; flow and sound together | Scales well on GPUs; good mid–high-frequency resolution | Large lattices at high Re; stability and BC tuning needed; modern formulations support high-Ma flows. | [64] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zou, T.; Fu, Y.; Cao, P. Vehicle Aerodynamic Noise: A Systematic Review of Mechanisms, Simulation Methods, and Bio-Inspired Mitigation Strategies. Biomimetics 2026, 11, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020099

Zou T, Fu Y, Cao P. Vehicle Aerodynamic Noise: A Systematic Review of Mechanisms, Simulation Methods, and Bio-Inspired Mitigation Strategies. Biomimetics. 2026; 11(2):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020099

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Tao, Yifeng Fu, and Pan Cao. 2026. "Vehicle Aerodynamic Noise: A Systematic Review of Mechanisms, Simulation Methods, and Bio-Inspired Mitigation Strategies" Biomimetics 11, no. 2: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020099

APA StyleZou, T., Fu, Y., & Cao, P. (2026). Vehicle Aerodynamic Noise: A Systematic Review of Mechanisms, Simulation Methods, and Bio-Inspired Mitigation Strategies. Biomimetics, 11(2), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020099