Space Human–Robot Interaction with Gaze Tracking Based on Attention Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Human–Robot Interaction Related Work

1.1.1. Human–Robot Interaction Mode

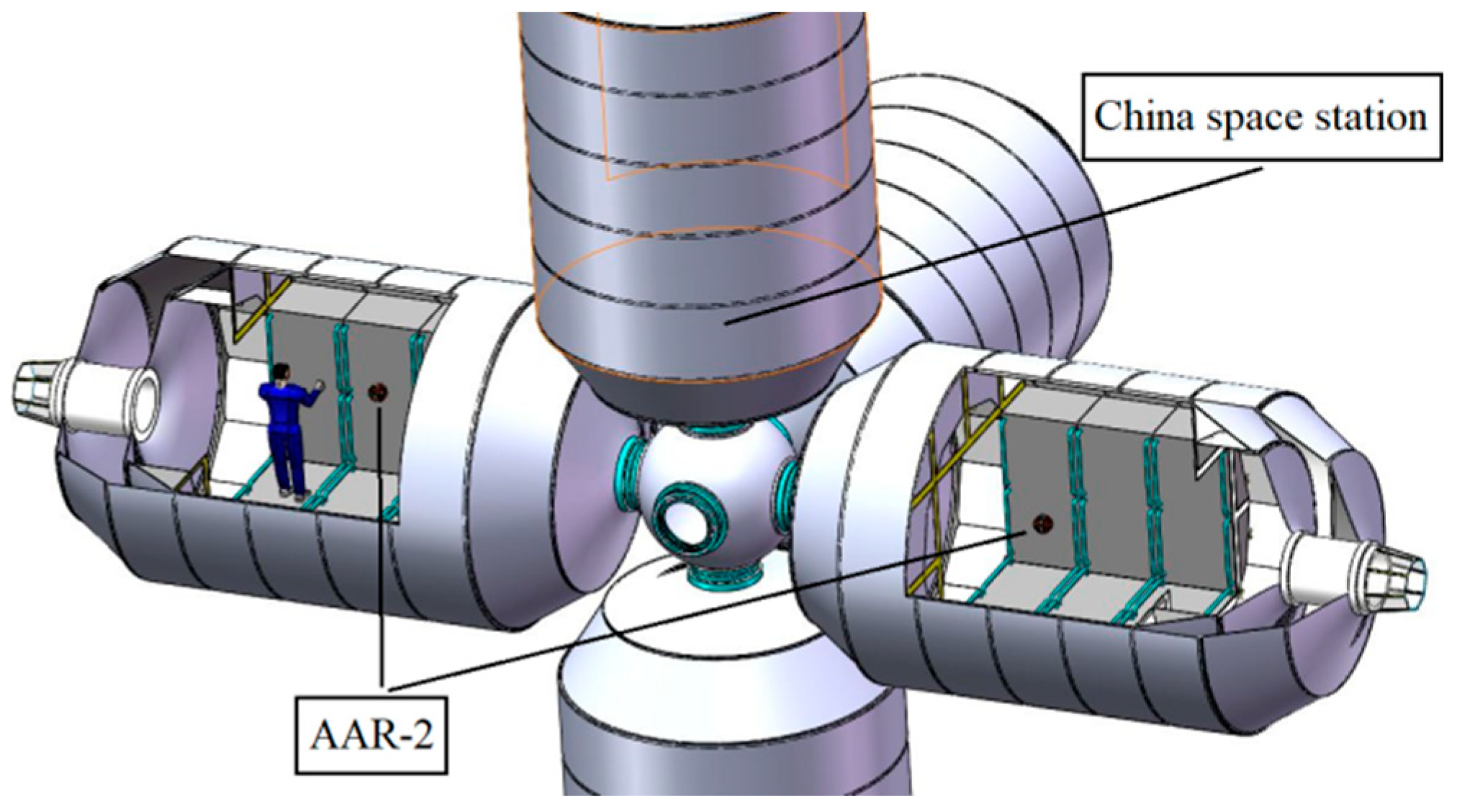

1.1.2. Space Human–Robot Interaction Platform

1.2. Related Work on Gaze Tracking Based on Attention Mechanisms

1.3. The Main Contribution

- (1)

- Gaze tracking is successfully developed and applied in space HRI. The movement of AAR-2 is controlled by the astronaut’s gaze, and its running state is fed back to the astronaut simultaneously.

- (2)

- Information transmission between the laptop computer and the STM32 microcontroller (a 32-bit controller by ST Microelectronics) in AAR-2 is achieved via radio frequency communication, enabling its free flight.

- (3)

- A gaze tracking database is established, and a highly accurate gaze tracking model based on the attention mechanism is proposed, providing opportunities for space HRI based on gaze.

- (4)

- In the process of image preprocessing, a series of measures are taken to improve the speed, enabling real-time gaze tracking.

2. The Proposed Gaze Tracking Approach Based on Attention Mechanism

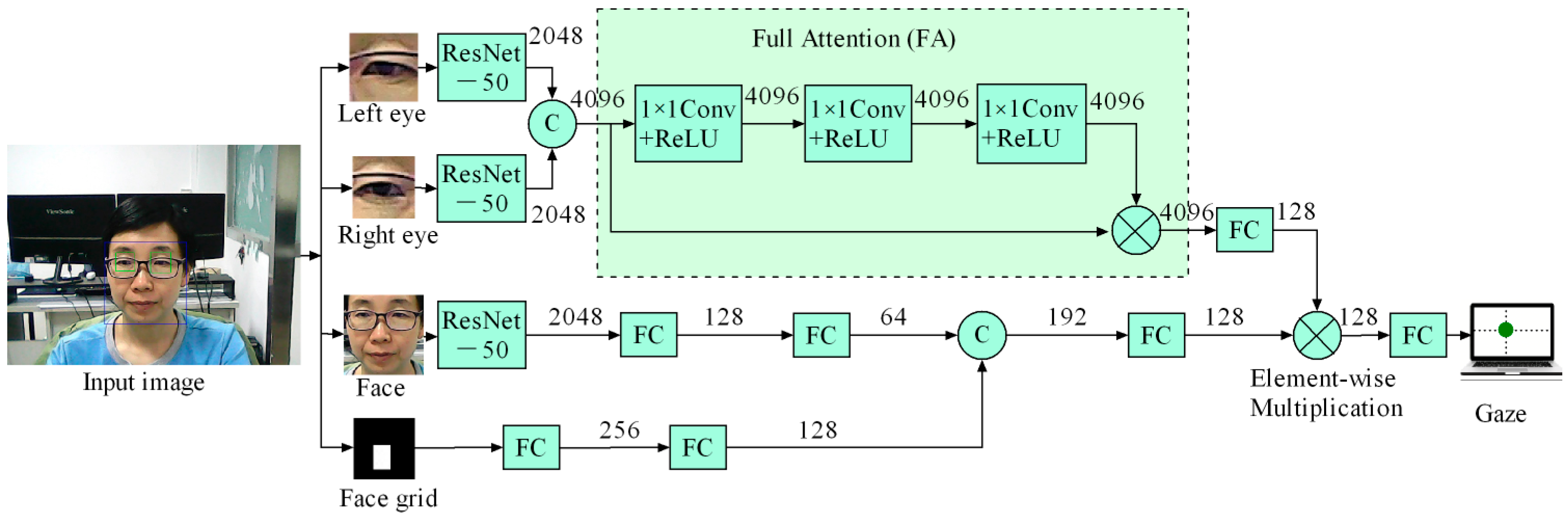

2.1. Proposed Gaze Tracking Method (BinocularFullAttention)

2.2. Proposed Full Attention Mechanism

2.3. Gaze Tracking Comparison Experiments

2.3.1. Comparison Experiments of Gaze Tracking with Other Attention Mechanisms

2.3.2. Comparison Experiments with Other State-of-the-Art Gaze Tracking Approaches

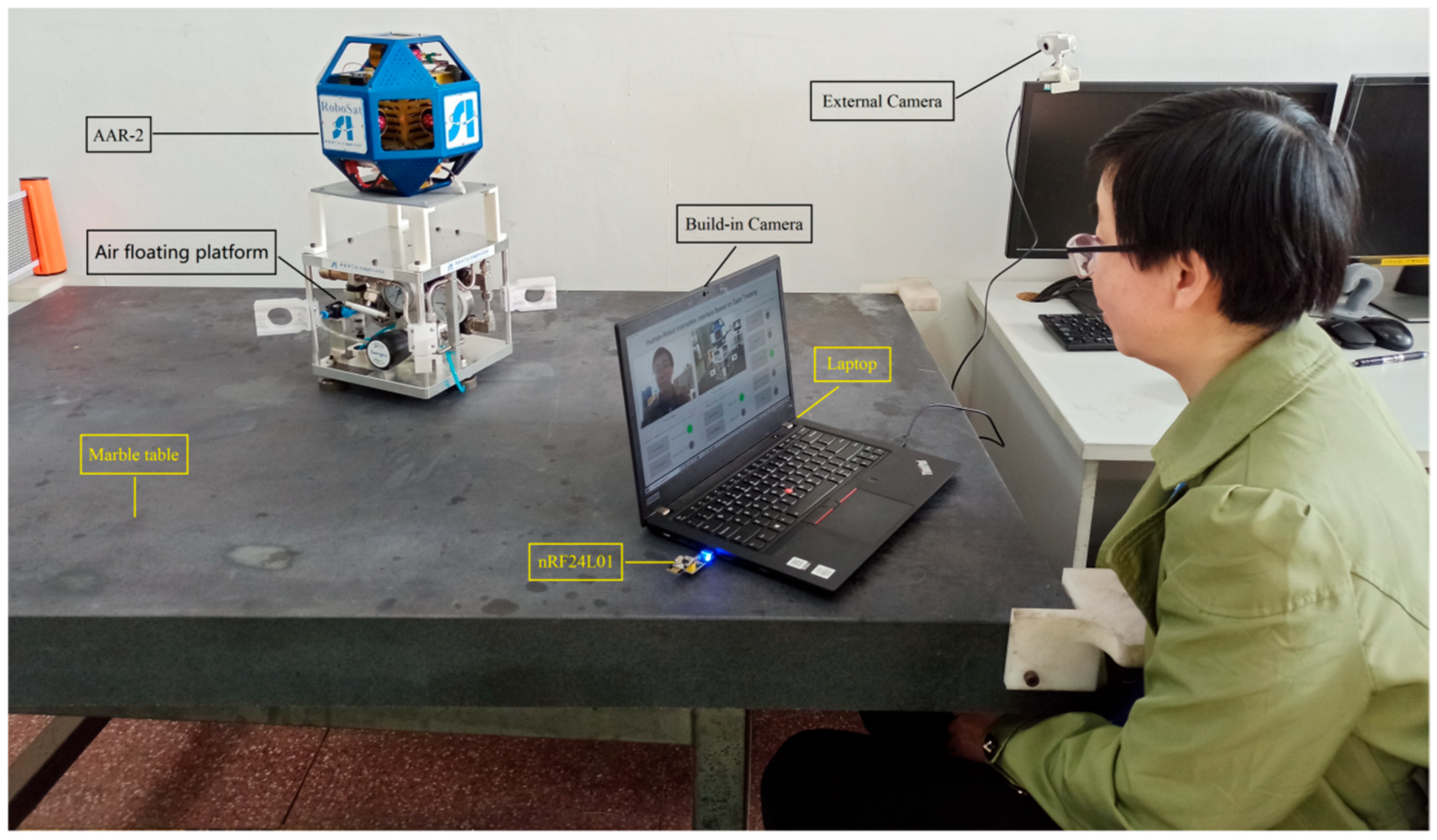

3. Space Human–Robot Interaction Experiment

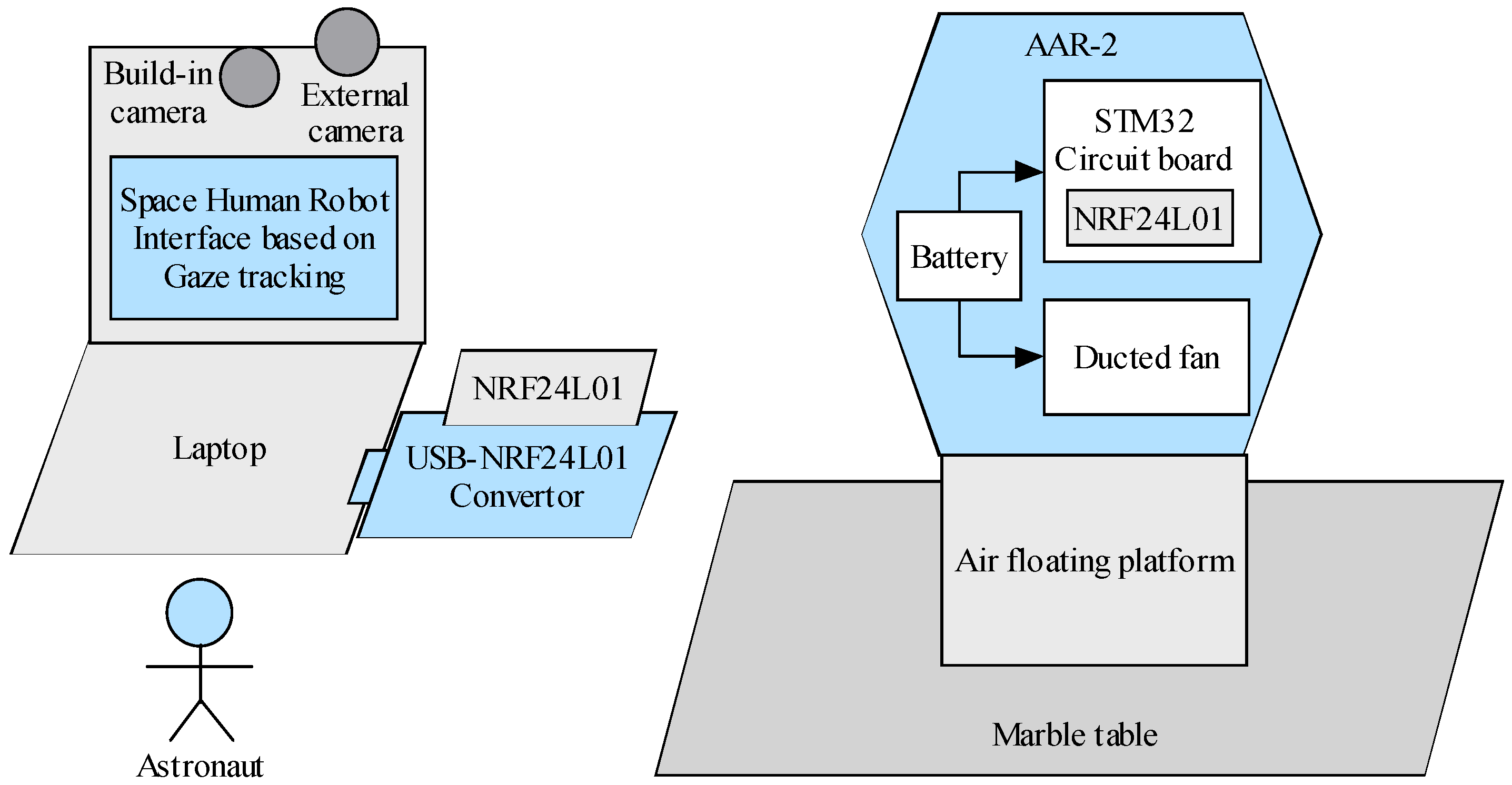

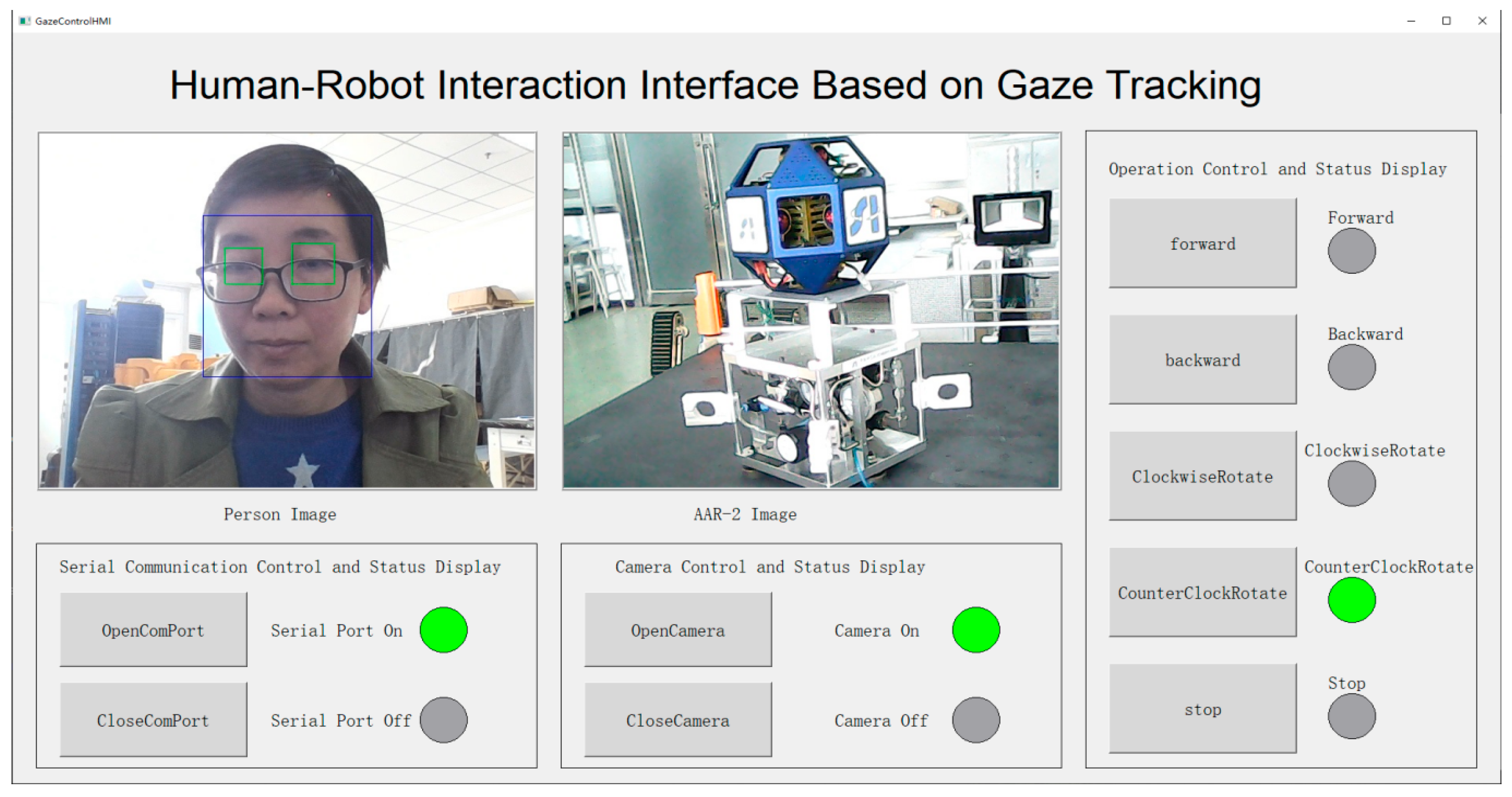

3.1. System Composition

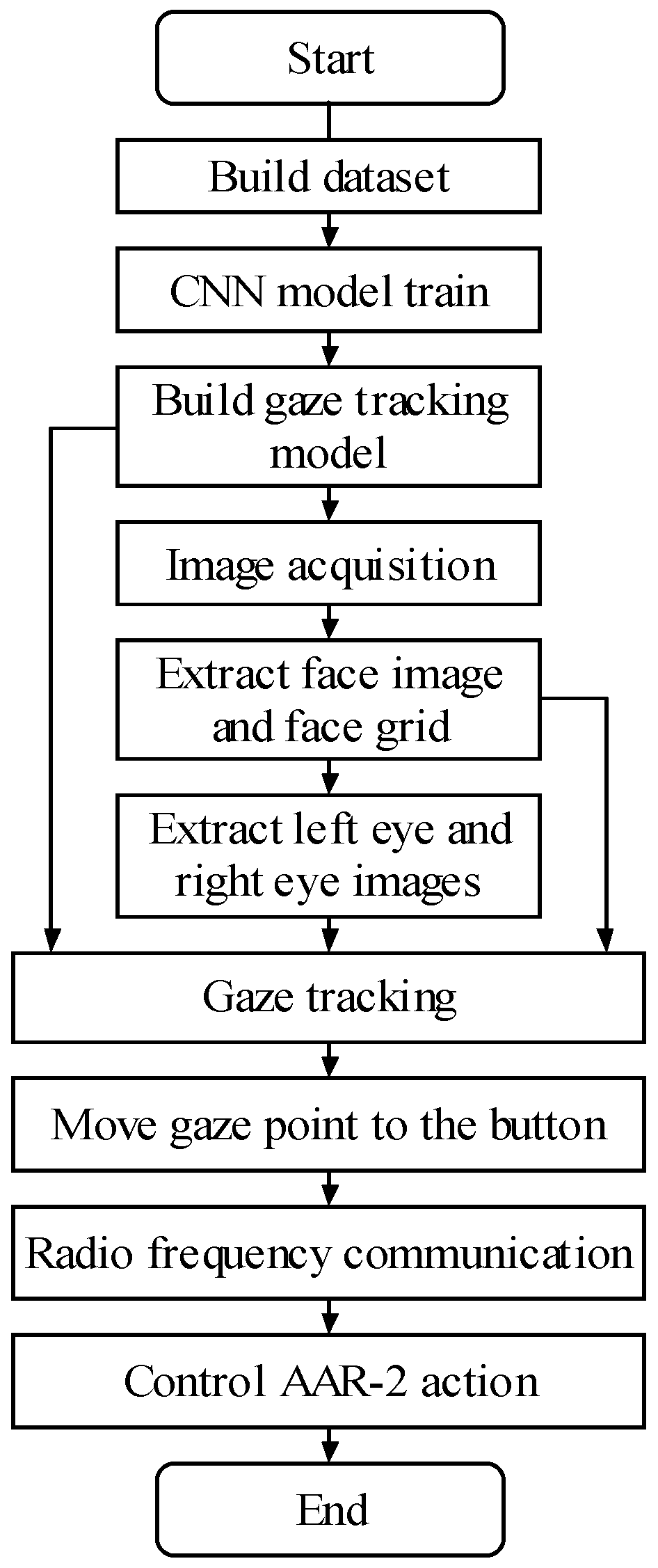

3.2. Implementation Details

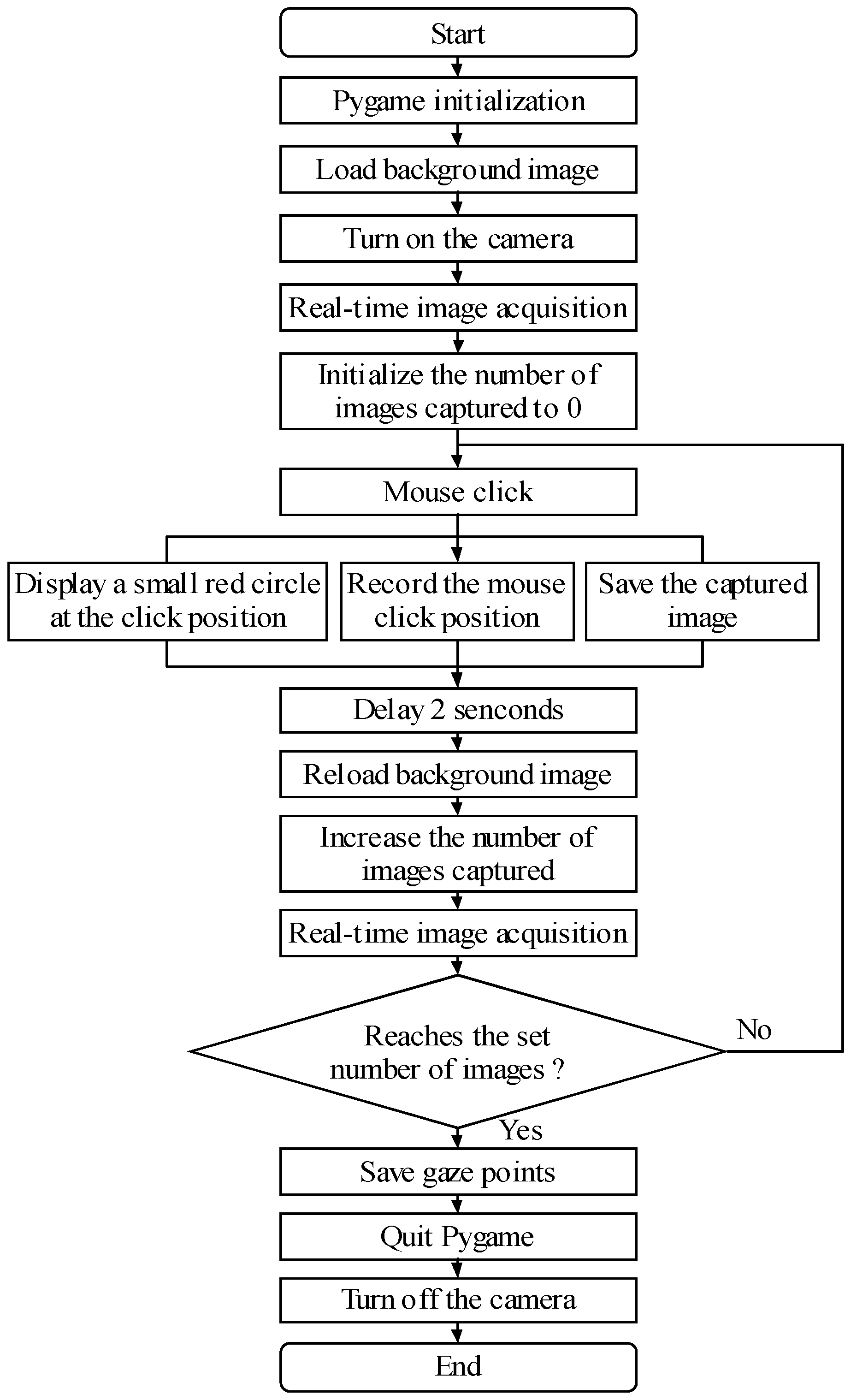

3.2.1. Establishment of Database and Model

3.2.2. Image Acquisition, Preprocessing, and Gaze Tracking

3.2.3. Human–Robot Interface

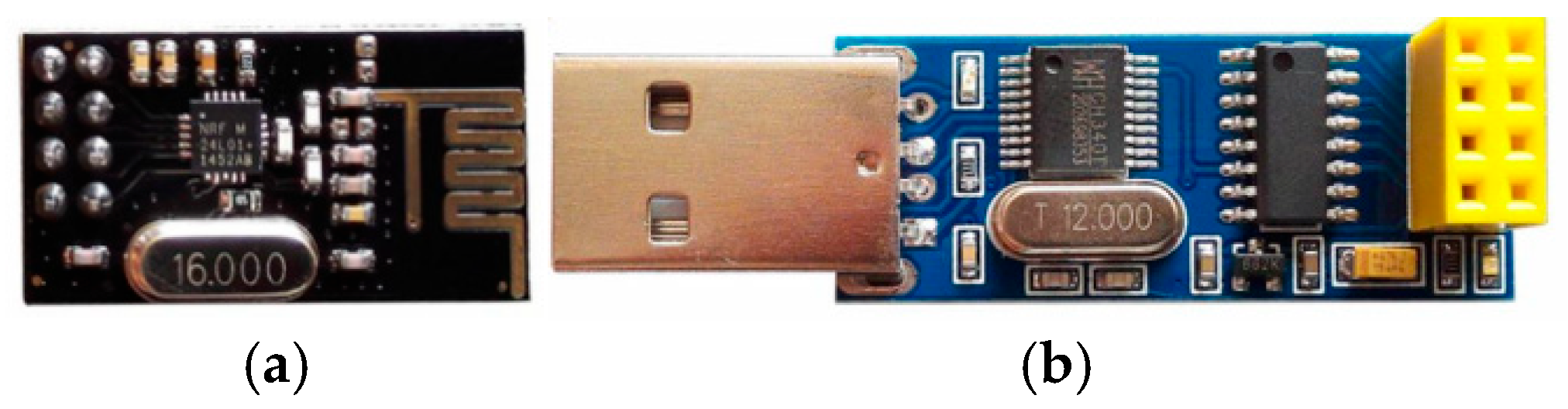

3.2.4. Radio Frequency Communication

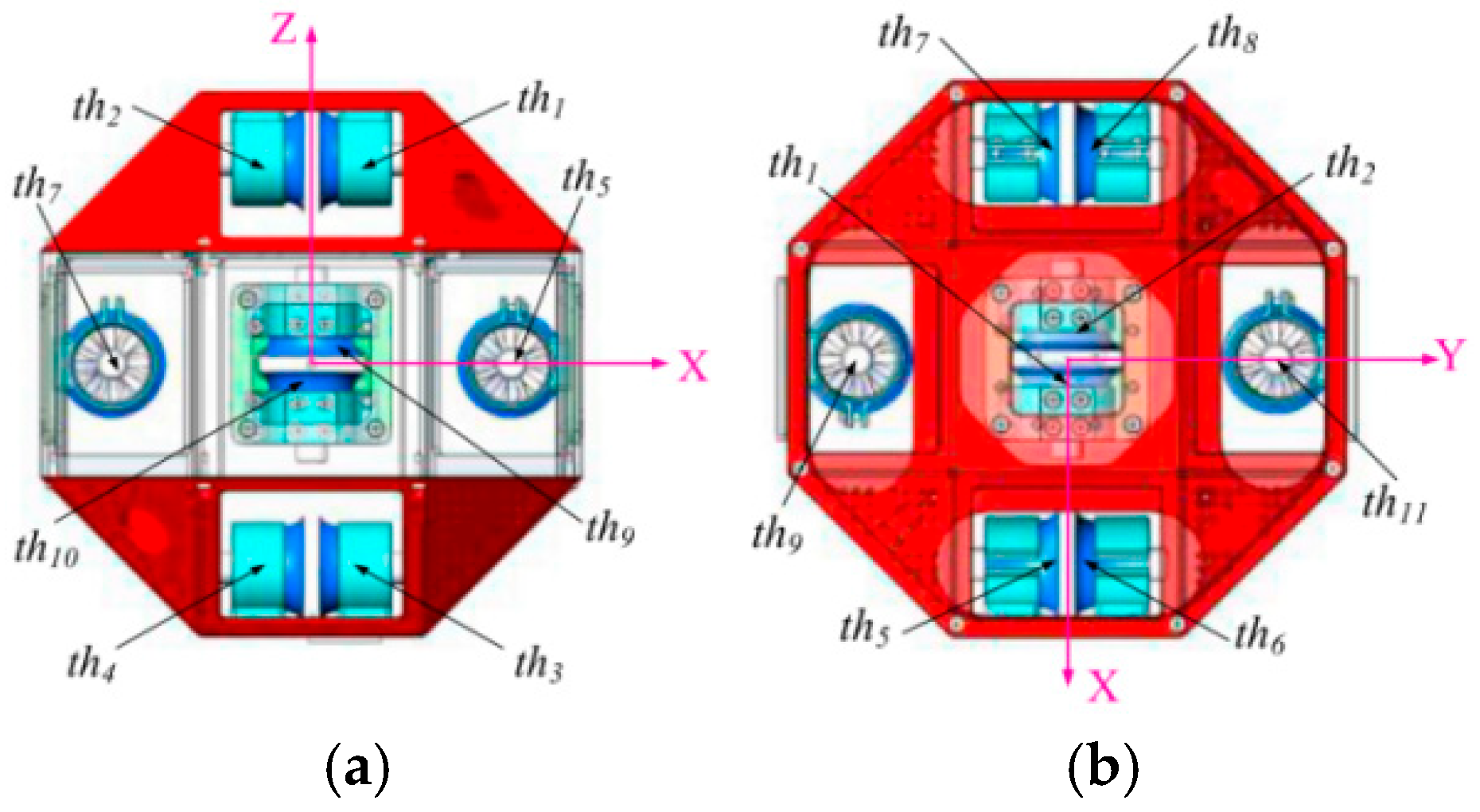

3.2.5. Control and Drive of Ducted Fan

3.3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.3.1. Comparative Analysis of Gaze Tracking Models with Various Attention Mechanisms

| Local Attention Mechanism | Global Attention Mechanism | Test Error (cm) | Time (Minute) /Epoch |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | 0.3912 | 6.0 |

| CA | N | 0.3638 | 6.6 |

| SA | N | 0.3248 | 7.6 |

| FA | N | 0.3022 | 7.9 |

| N | Y | 0.3737 | 6.0 |

| CA | Y | 0.3552 | 6.8 |

| SA | Y | 0.3090 | 7.8 |

| FA | Y | 0.2852 | 7.9 |

3.3.2. Physical Scene Visualization in Space Human–Robot Interaction Simulation Experiment

3.4. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAR-2 | The Second-Generation Astronaut-Assistant Robot |

| BRI | Brain–robot interface |

| CA | Channel attention |

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| ECA | Efficient channel attention |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| FA | Full attention |

| FC | Fully connected |

| GAM | Global attention mechanism |

| HRI | Human–robot interaction |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| SA | Spatial attention |

Appendix A

| Algorithm A1: Determin face grid region | |

| Input: | |

| The width and height of Input image: Wi, Hi The left top coordinate of face ROI: Xf, Yf The width and height of face ROI: Wf, Hf | |

| Compute process: | |

| factor 1 = 25/Wi factor 2 = 25/Hi XGrid = Xf ∗ factor 1 YGrid = Yf ∗ factor 2 WGrid = Wf ∗ factor 1 HGrid = Hf ∗ factor 2 | |

| Output: | |

| The left top coordinate of face grid: XGrid, YGrid The width and height of face grid: WGrid, HGrid | |

Appendix B

| Algorithm A2: Determin eye ROI | |

| Input: | |

| The coordinate of left canthus: Xcl, Ycl The coordinate of right canthus: Xcr, Ycr | |

| Compute process: | |

| width = Xcr − Xcl midY = (Ycl + Ycr)/2 X = Xcl − 0.25 ∗ width Y = midY − 0.75 ∗ width W = 1.5 ∗ width H = W | |

| Output: | |

| The left top coordinate of eye ROI: X, Y The width and height of eye ROI: W, H | |

Appendix C

| Algorithm A3: Left eye ROI limitation | |

| Input: | |

| The width of face image: Wf The left top coordinate of left eye ROI: Xleft, Yleft The width and height of left eye: Wleft, Hleft | |

| if(Xleft > Wf − Wleft and Yleft >= 0) then{ Wleft = Wf − Xleft Hleft = Wleft } if(Yleft < 0 And Xleft <= Wf − Wleft) then{ Hleft = Hleft + Yleft Wleft = Hleft Yleft = 0 } if(Yleft < 0 And Xleft > Wf − Wleft) then{ if(Yleft + Hleft < Wf − Xleft) then{ Hleft = Hleft + Yleft Wleft = Hleft Yleft = 0 } else { Wleft = Wf − Xleft Hleft = Wleft Yleft = 0 } } | |

| Output: | |

| The left top coordinate of left eye ROI: Xleft, Yleft The width and height of left eye ROI: Wleft, Hleft | |

References

- Huang, F.; Sun, X.; Xu, Q.; Cheng, W.; Shi, Y.; Pan, L. Recent Developments and Applications of Tactile Sensors with Biomimetic Microstructures. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.J.; Fitter, N.T. Nonverbal Sound in Human-Robot Interaction: A Systematic Review. ACM Trans. Hum.-Robot Interact. 2023, 12, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Li, Z.; Su, C.Y. Multisensor-Based Navigation and Control of a Mobile Service Robot. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2021, 51, 2624–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Liu, J.G.; Ju, Z.J. Robust real-time hand detection and localization for space human-robot interaction based on deep learning. Neurocomputing 2020, 390, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moysiadis, V.; Katikaridis, D.; Benos, L.; Busato, P.; Anagnostis, A.; Kateris, D.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. An Integrated Real-Time Hand Gesture Recognition Framework for Human-Robot Interaction in Agriculture. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwolek, B. Continuous Hand Gesture Recognition for Human-Robot Collaborative Assembly. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) Workshops, Paris, France, 4–6 October 2023; pp. 2000–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Zhang, Y.F.; Yao, Y. Digital twins for hand gesture-guided human-robot collaboration systems. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B-J. Eng. Manuf. 2024, 238, 2060–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Rodicio, E.; Dondrup, C.; Sevilla-Salcedo, J.; Castro-González, Á.; Salichs, M.A. Predicting and Synchronising Co-Speech Gestures for Enhancing Human–Robot Interactions Using Deep Learning Models. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Su, W.; Chen, L.; Liu, Z.; Cao, W.; Hirota, K. Weight-Adapted Convolution Neural Network for Facial Expression Recognition in Human–Robot Interaction. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2021, 51, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Hong, S. The Development of Human-Robot Interaction Design for Optimal Emotional Expression in Social Robots Used by Older People: Design of Robot Facial Expressions and Gestures. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 21367–21381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, K.; Sathishkumar, S.; Sivachitra, M.; Dineshkumar, S.; Sathiyabama, P. Facial Expression Recognition Using Enhanced Convolution Neural Network with Attention Mechanism. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2022, 41, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, R.; Moreno, P.; Vourvopoulos, A. EEG-based action anticipation in human-robot interaction: A comparative pilot study. Front. Neurorobot. 2024, 18, 1491721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Rajabi, N.; Taleb, F.; Matviienko, A.; Ma, Y.; Björkman, M.; Kragic, D.J. Mind Meets Robots: A Review of EEG-Based Brain-Robot Interaction Systems. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 12784–12815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; He, B.; Xun, Z.; Xu, C.; Gao, F. GPA-Teleoperation: Gaze Enhanced Perception-Aware Safe Assistive Aerial Teleoperation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 5631–5638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, J.; Morimoto, J.; Kaji, Y.; Higuchi, M.; Fujisawa, S. Development of a Gaze-Driven ElectricWheelchair with 360° Camera and Novel Gaze Interface. J. Robot. Mechatron. 2023, 35, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Santos, V.J. Gaze-Based Shared Autonomy Framework with Real-Time Action Primitive Recognition for Robot Manipulators. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2023, 31, 4306–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Su, Y.; Navab, N.; Jiang, Z.L. Gaze-Guided Robotic Vascular Ultrasound Leveraging Human Intention Estimation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 3078–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, Q.; Huang, J.; Liu, C.; Cao, Z.; Chen, Y. A Novel Robotic Guidance System with Eye-Gaze Tracking Control for Needle-Based Interventions. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2021, 13, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Bourdonnaye, F.; Setchi, R.; Zanni-Merk, C. Gaze Trajectory Prediction in the Context of Social Robotics. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2016, 49, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Elibol, A.; Chong, N.Y. Multi-modal feature fusion for better understanding of human personality traits in social human–robot interaction. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2021, 146, 103874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaignan, S.; Warnier, M.; Sisbot, E.A.; Clodic, A.; Alami, R. Artificial cognition for social human–robot interaction: An implementation. Artif. Intell. 2017, 247, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, P. Review of Crew Equipment Onboard International Space Station and Its Health Management Techniques. Manned Spacefl. 2025, 31, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Liu, J.; Ju, Z.; Liu, Y. Real-Time HALCON-Based Pose Measurement System for an Astronaut Assistant Robot. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Intelligent Robotics and Applications (ICIRA 2018), Newcastle, Australia, 9–11 August 2018; pp. 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittman, D.; Wheeler, D.W.; Torres, R.J.; To, V.; Smith, E.; Provencher, C.; Park, E.; Morse, T.; Fong, T.; Micire, M. Smart SPHERES: A Telerobotic Free-Flyer for Intravehicular Activities in Space. In Proceedings of the AIAA SPACE 2013 Conference and Exposition, San Diego, CA, USA, 10–12 September 2013; p. 5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bualat, M.; Barlow, J.; Fong, T.; Provencher, C.; Smith, T. Astrobee: Developing a Free-flying Robot for the International Space Station. In Proceedings of the AIAA SPACE 2015 Conference and Exposition, Pasadena, CA, USA, 31 August–2 September 2015; p. 4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.; Persaud, R.; Tasnim, M.; Khandaker, N.I.; Singh, O. The CIMON (Crew Interactive Mobile Companion): Geological Mapping of the Martian Terrain. Geol. Soc. Am. Abstr. Programs 2020, 52, 355046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitani, S.; Goto, M.; Konomura, R.; Shoji, Y.; Hagiwara, K.; Shigeto, S.; Tanishima, N. Int-Ball: Crew-Supportive Autonomous Mobile Camera Robot on ISS/JEM. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 2–9 March 2019; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.P.; Yamamoto, T.; Watanabe, H.; Itakura, R.; Wada, M.; Mitani, S.; Hirano, D.; Watanabe, K.; Nishishita, T.; Kawai, Y. Int-ball2: Iss jem internal camera robot with increased degree of autonomy–design and initial checkout. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Space Robotics (iSpaRo), Luxembourg, 24–27 June 2024; pp. 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, D.; Mitani, S.; Watanabe, K.; Nishishita, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Yamaguchi, S.P. Int-Ball2: On-Orbit Demonstration of Autonomous Intravehicular Flight and Docking for Image Capturing and Recharging. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2024, 32, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Liu, J.G.; Tian, T.T.; Li, Y.M. Free-flying dynamics and control of an astronaut assistant robot based on fuzzy sliding mode algorithm. Acta Astronaut. 2017, 138, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Liu, J.; Ju, Z. Attention Mechanism and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory-Based Real-Time Gaze Tracking. Electronics 2024, 13, 4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sugano, Y.; Fritz, M.; Bulling, A. It’s Written All Over Your Face: Full-Face Appearance-Based Gaze Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2299–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Liu, J.; Ju, Z.; Gao, Y. Attention Mechanism based Real Time Gaze Tracking in Natural Scenes with Residual Blocks. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2022, 14, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Liu, J.; Ju, Z. Binocular Feature Fusion and Spatial Attention Mechanism Based Gaze Tracking. IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach. Syst. 2022, 52, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafka, K.; Khosla, A.; Kellnhofer, P.; Kannan, H.; Bhandarkar, S.; Matusik, W.; Torralba, A. Eye Tracking for Everyone. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2176–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Kwak, Y.; Yoo, B.I.; Han, J.; Choi, C. A Generalized and Robust Method Towards Practical Gaze Estimation on Smart Phone. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop (ICCVW), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019; pp. 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S. Basic Introduction to PyGame. In Python, PyGame and Raspberry Pi Game Development; Kelly, S., Ed.; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.E. Dlib-ml: A Machine Learning Toolkit. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2009, 10, 1755–1758. [Google Scholar]

- Naveenkumar, M.; Vadivel, A. OpenCV for computer vision applications. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2025, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Local Attention Mechanism | Global Attention Mechanism | Test Error (cm) | Time (Minute) /Epoch |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | 2.4255 | 78.1 |

| CA | N | 2.3920 | 86.0 |

| SA | N | 2.3831 | 98.9 |

| FA | N | 2.3623 | 99.3 |

| N | Y | 2.3839 | 78.4 |

| CA | Y | 2.3522 | 88.6 |

| SA | Y | 2.3306 | 99.7 |

| FA | Y | 2.3112 | 99.9 |

| Model | Test Error (cm) |

|---|---|

| iTracker without augment [35] | 2.23 |

| iTracker with augment [35] | 1.93 |

| TAT [36] | 1.95 |

| SA + GAM [34] | 1.86 |

| SpatiotemporalAM [31] | 1.92 |

| BinocularFullAttention | 1.82 |

| Start Byte | Control Flag | Forward Move | Backward Move | Counterclockwise Rotate | Clockwise Rotate | End Byte |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aa | f9 | ff/00 | ff/00 | ff/00 | ff/00 | dd |

| BN | Start Byte | Control Flag | Forward Move | Backward Move | Counterclockwise Rotate | Clockwise Rotate | End Byte |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 170 | 9 | 255/0 | 255/0 | 255/0 | 255/0 | 221 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dai, L.; Liu, J.; Ju, Z. Space Human–Robot Interaction with Gaze Tracking Based on Attention Mechanism. Biomimetics 2026, 11, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020103

Dai L, Liu J, Ju Z. Space Human–Robot Interaction with Gaze Tracking Based on Attention Mechanism. Biomimetics. 2026; 11(2):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020103

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Lihong, Jinguo Liu, and Zhaojie Ju. 2026. "Space Human–Robot Interaction with Gaze Tracking Based on Attention Mechanism" Biomimetics 11, no. 2: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020103

APA StyleDai, L., Liu, J., & Ju, Z. (2026). Space Human–Robot Interaction with Gaze Tracking Based on Attention Mechanism. Biomimetics, 11(2), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020103