Design Features of a Titanium Mesh for Guided Bone Regeneration and In Vivo Testing in Vitamin D3 Deficiency Condition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

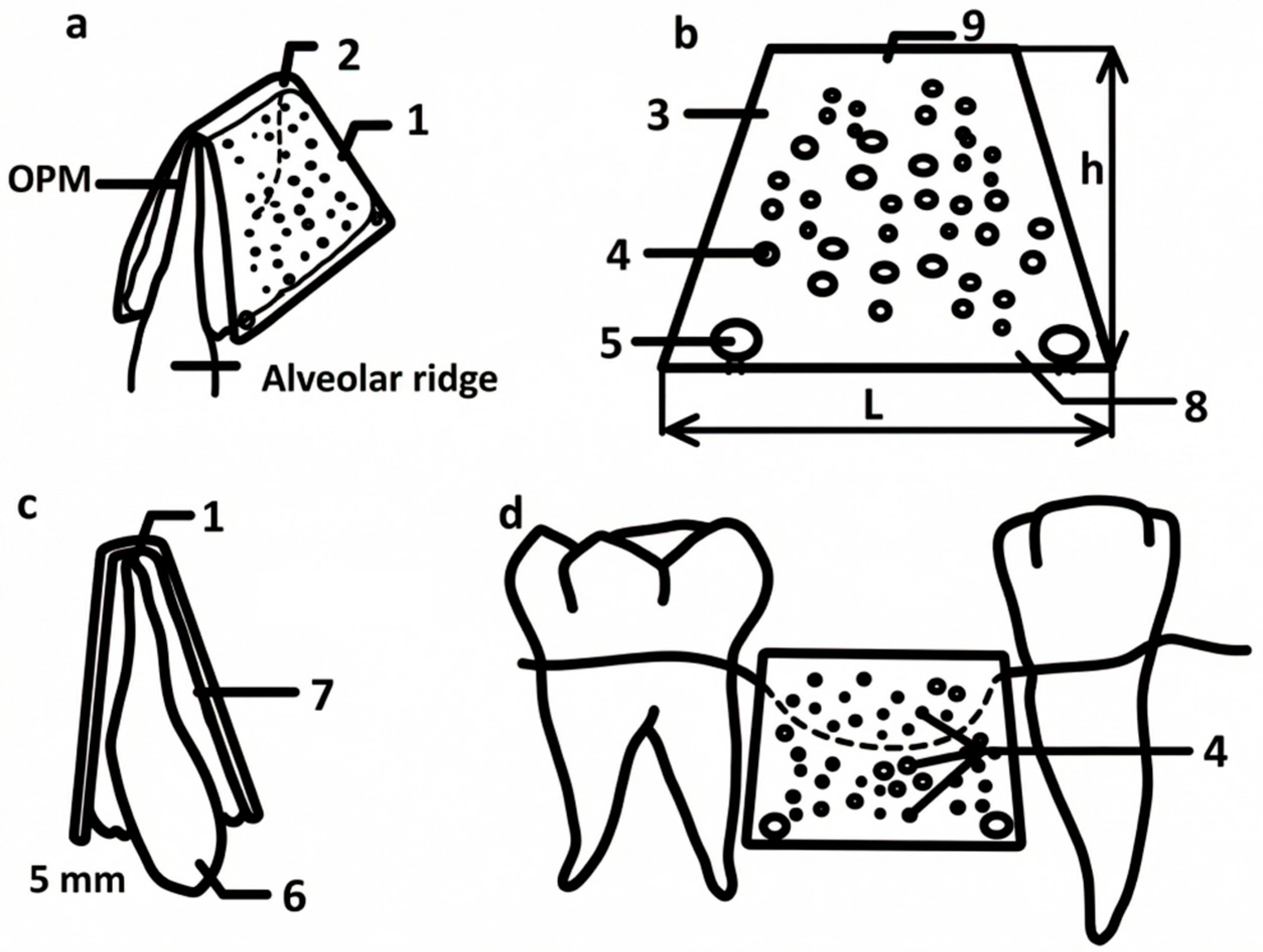

2.1. Titanium Mesh Design

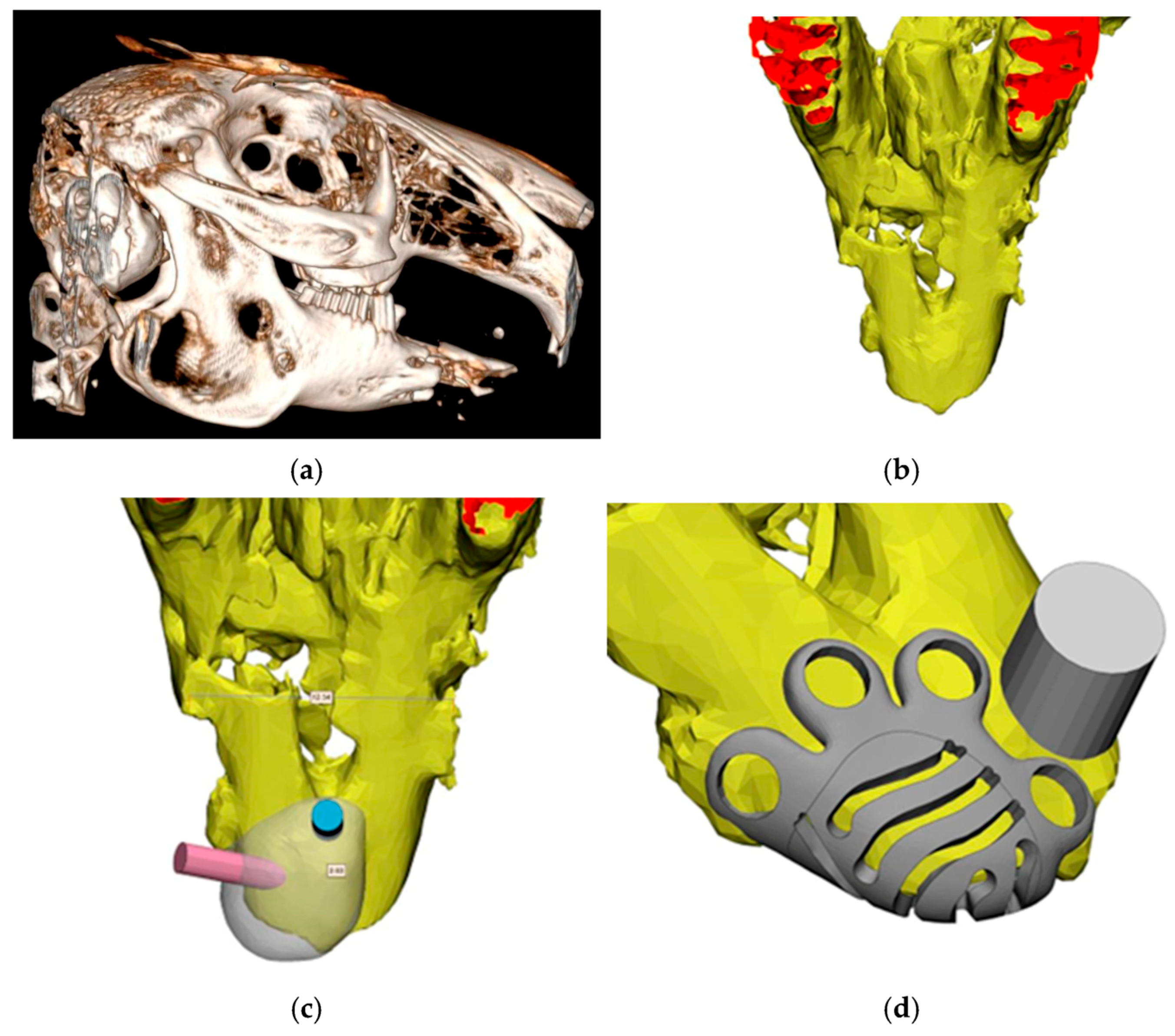

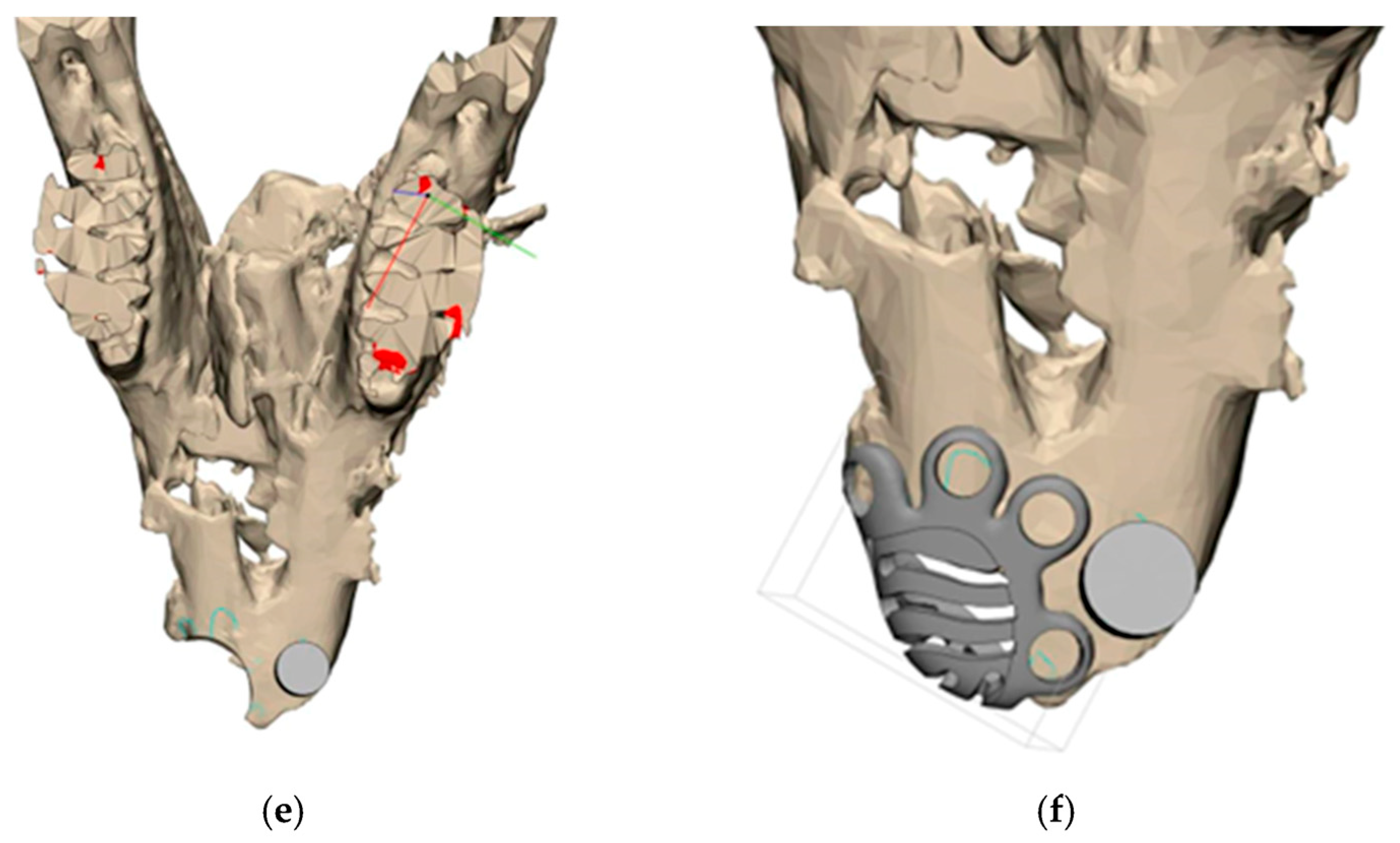

2.2. Testing In Vivo

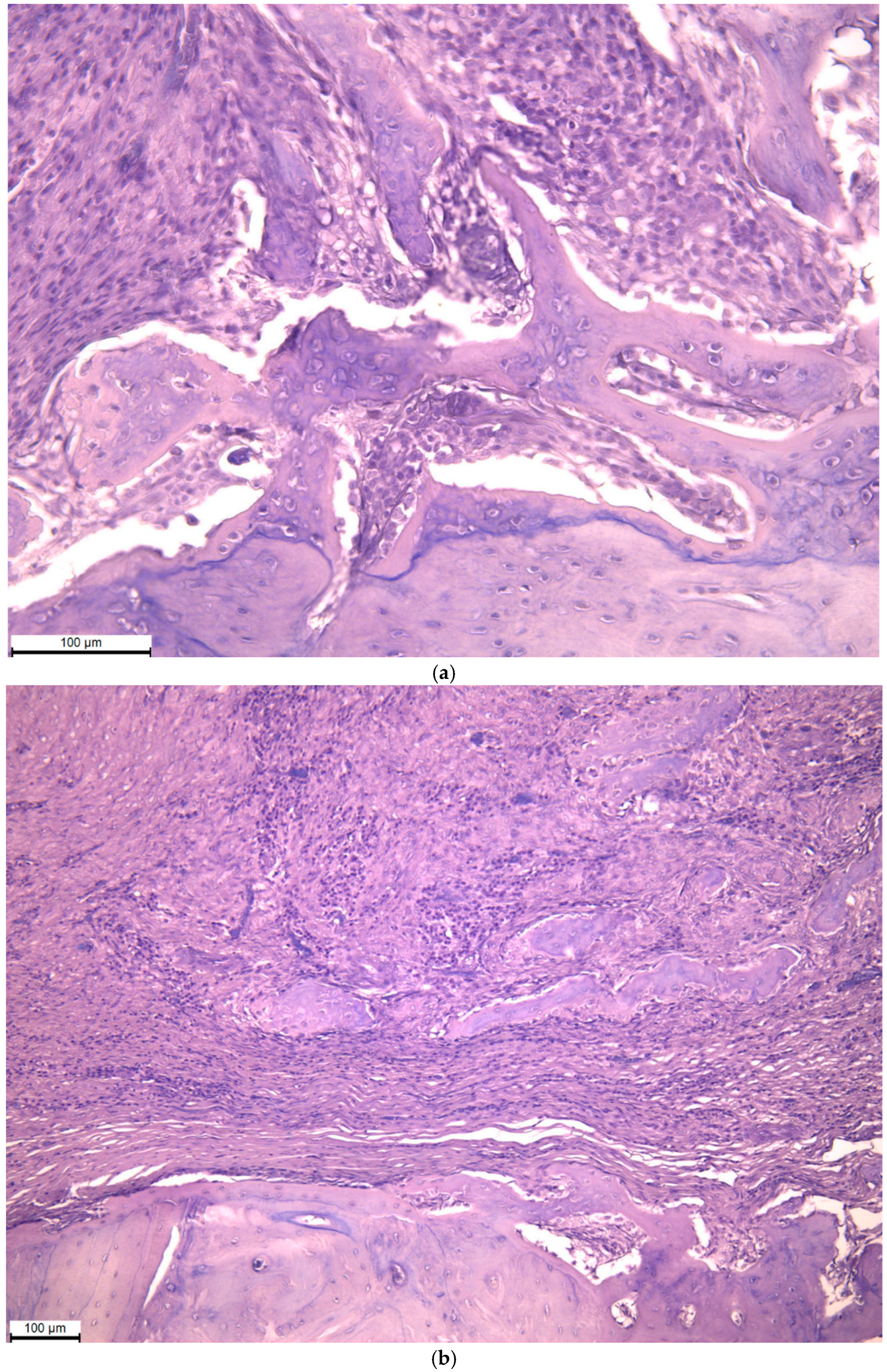

2.3. Histological Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Titanium Mesh Design

3.2. Testing In Vivo

3.3. Histological Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBCT | Cone beam computed tomography |

References

- Dioguardi, M.; Spirito, F.; Quarta, C.; Sovereto, D.; Basile, E.; Ballini, A.; Caloro, G.A.; Troiano, G.; Muzio, L.L.; Mastrangelo, F. Guided dental implant surgery: Systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buser, D.; Urban, I.; Monje, A.; Kunrath, M.F.; Dahlin, C. Guided bone regeneration in implant dentistry: Basic principle, progress over 35 years, and recent research activities. Periodontology 2000 2023, 93, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antón, M.M.; Pérez-González, F.; Meniz-García, C. Titanium mesh for guided bone regeneration: A systematic review. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 62, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scribante, A.; Ghizzoni, M.; Pellegrini, M.; Pulicari, F.; Manfredini, M.; Poli, P.P.; Maiorana, C.; Spadari, F. Full-digital customized meshes in guided bone regeneration procedures: A scoping review. Prosthesis 2023, 5, 480–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.; Mahajan, H.; Somkuwar, K. Residual Alveolar Ridge Resorption; Shineeks Publishers: Hyderabad, India, 2022; 67p, ISBN 978-1-63278-957-0. [Google Scholar]

- Diachkova, E.; Petukhova, M.; Zhilkov, Y.; Osmanov, P.; Pchelyakov, A.; Tarasenko, S.; Taschieri, S.; Runova, G.; Fadeev, V.; Shalnova, S.; et al. Investigating the Effect of Vitamin D3 on Osseointegration of Dental Implants in Rabbits: An Experimental Pilot Study. Int. J. Dent. 2024, 2024, 5584551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diachkova, E.Y.; Ershov, B.P.; Demyanenko, I.A.; Kalmykova, N.V.; Faizullin, A.L.; Marahovskaya, A.A.; Petukhova, M.M. Elimination of critical jawbone defects using xenogenic collagen membranes and amorphous hydroxyapatite: An experimental study. Klin. Stomatol. 2024, 27, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, M.; Castro, F.; Macedo, J.P.; Lopes, O.; Pereira, J.; Lopes, P.; Fernandes, G.V. Mechanisms of degradation of collagen or gelatin materials (hemostatic sponges) in oral surgery: A systematic review. Surgeries 2024, 5, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocca, G.; Filetici, P.; Bugli, F.; Mordente, A.; D’Addona, A.; Dassatti, L. Permeability of P. gingivalis or its metabolic products through collagen and dPTFE membranes and their effects on the viability of osteoblast-like cells: An in vitro study. Odontology 2022, 110, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoshin, A.; Dubinin, O.; Miao, L.; Istranova, E.; Bikmulina, P.; Fayzullin, A.; Magdanov, A.; Kravchik, M.; Kosheleva, N.; Solovieva, A.; et al. Semipermeable Barrier-Assisted Electrophoretic Deposition of Robust Collagen Membranes. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 9675–9697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, G.; Carvalho, P.H.; Quirino, L.C.; Torres, L.H.; Filho, V.A.; Gabrielli, M.F.; Gabrielli, M.A. Titanium mesh exposure after bone grafting: Treatment approaches—A systematic review. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstr. 2022, 15, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellavia, C.; Canciani, E.; Pellegrini, G.; Tommasato, G.; Graziano, D.; Chiapasco, M. Histological assessment of mandibular bone tissue after guided bone regeneration with customized computer-aided design/computer-assisted manufacture titanium mesh in humans: A cohort study. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2021, 23, 600–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muresan, G.C.; Hedesiu, M.; Lucaciu, O.; Boca, S.; Petrescu, N. Effect of vitamin D on bone regeneration: A review. Medicina 2022, 58, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhad, A. The role of vitamin D levels in early dental implant failure. J. Long-Term Eff. Med. Implant. 2023, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedik, B.; Kasapoglu, M.B.; Dogancali, G.E.; Uckun, G.G.; Cankaya, A.B.; Erdem, M.A. Effect of different titanium mesh thicknesses on mechanical strength and bone stress: A finite element study. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, N.C.; Bissada, N.F.; Davidovitch, Z.E.; Kucska, S. Corticotomy and stem cell therapy for orthodontists and periodontists: Rationale, hypotheses, and protocol. Integr. Clin. Orthod. 2012, 18, 392–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, R.; Shahgholi, M.; Khandan, A. Fabrication and characterization of reinforced glass ionomer cement by zinc oxide and hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criteria | Day 3 | Day 5 | Day 7 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edema | ||||

| Me ± m | 1.67 ± 0.2 | 1 | 0 | <0.05 (0.00001) |

| Median | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Min-max | 1–2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Hyperemia | ||||

| Me ± m | 1.33 ± 0.52 | 1 | 0 | <0.05 (0.000042) |

| Median | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Min-max | 1–2 | 1 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Diachkova, E.; Kazumova, A.; Shamanaev, A.; Shcherbinina, L.; Gulyaev, A.; Vasil’ev, Y.; Petruk, P.; Brago, A.; Enina, Y.; Chilikov, V.; et al. Design Features of a Titanium Mesh for Guided Bone Regeneration and In Vivo Testing in Vitamin D3 Deficiency Condition. Biomimetics 2026, 11, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020091

Diachkova E, Kazumova A, Shamanaev A, Shcherbinina L, Gulyaev A, Vasil’ev Y, Petruk P, Brago A, Enina Y, Chilikov V, et al. Design Features of a Titanium Mesh for Guided Bone Regeneration and In Vivo Testing in Vitamin D3 Deficiency Condition. Biomimetics. 2026; 11(2):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020091

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiachkova, Ekaterina, Aglaya Kazumova, Andrei Shamanaev, Liubov Shcherbinina, Alexandr Gulyaev, Yuriy Vasil’ev, Pavel Petruk, Anzhela Brago, Yulianna Enina, Valerii Chilikov, and et al. 2026. "Design Features of a Titanium Mesh for Guided Bone Regeneration and In Vivo Testing in Vitamin D3 Deficiency Condition" Biomimetics 11, no. 2: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020091

APA StyleDiachkova, E., Kazumova, A., Shamanaev, A., Shcherbinina, L., Gulyaev, A., Vasil’ev, Y., Petruk, P., Brago, A., Enina, Y., Chilikov, V., Darawsheh, H., Makeeva, E., & Tarasenko, S. (2026). Design Features of a Titanium Mesh for Guided Bone Regeneration and In Vivo Testing in Vitamin D3 Deficiency Condition. Biomimetics, 11(2), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020091