Theoretical Dynamics Modeling of Pitch Motion and Obstacle-Crossing Capability Analysis for Articulated Tracked Vehicles Based on Myriapod Locomotion Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

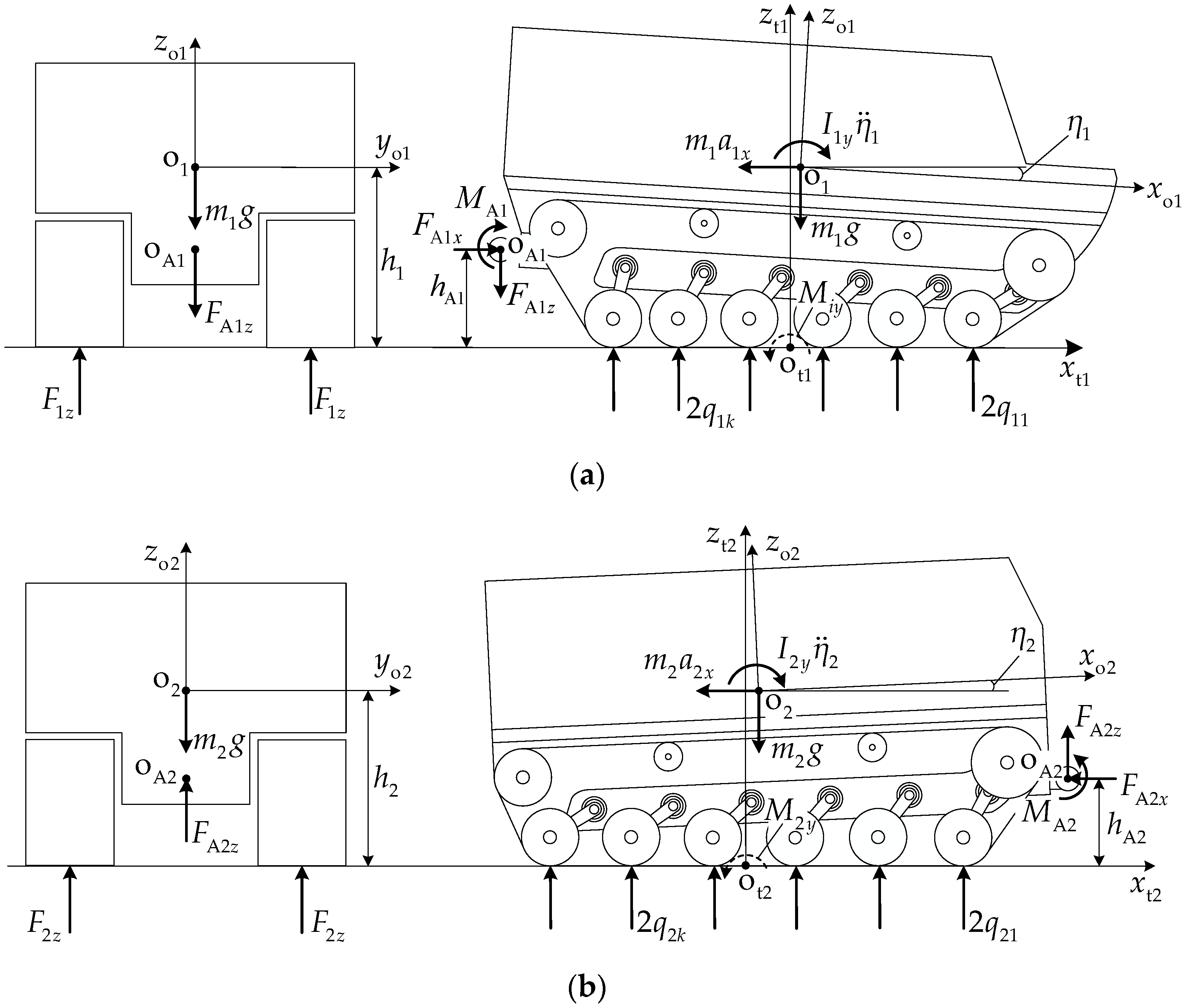

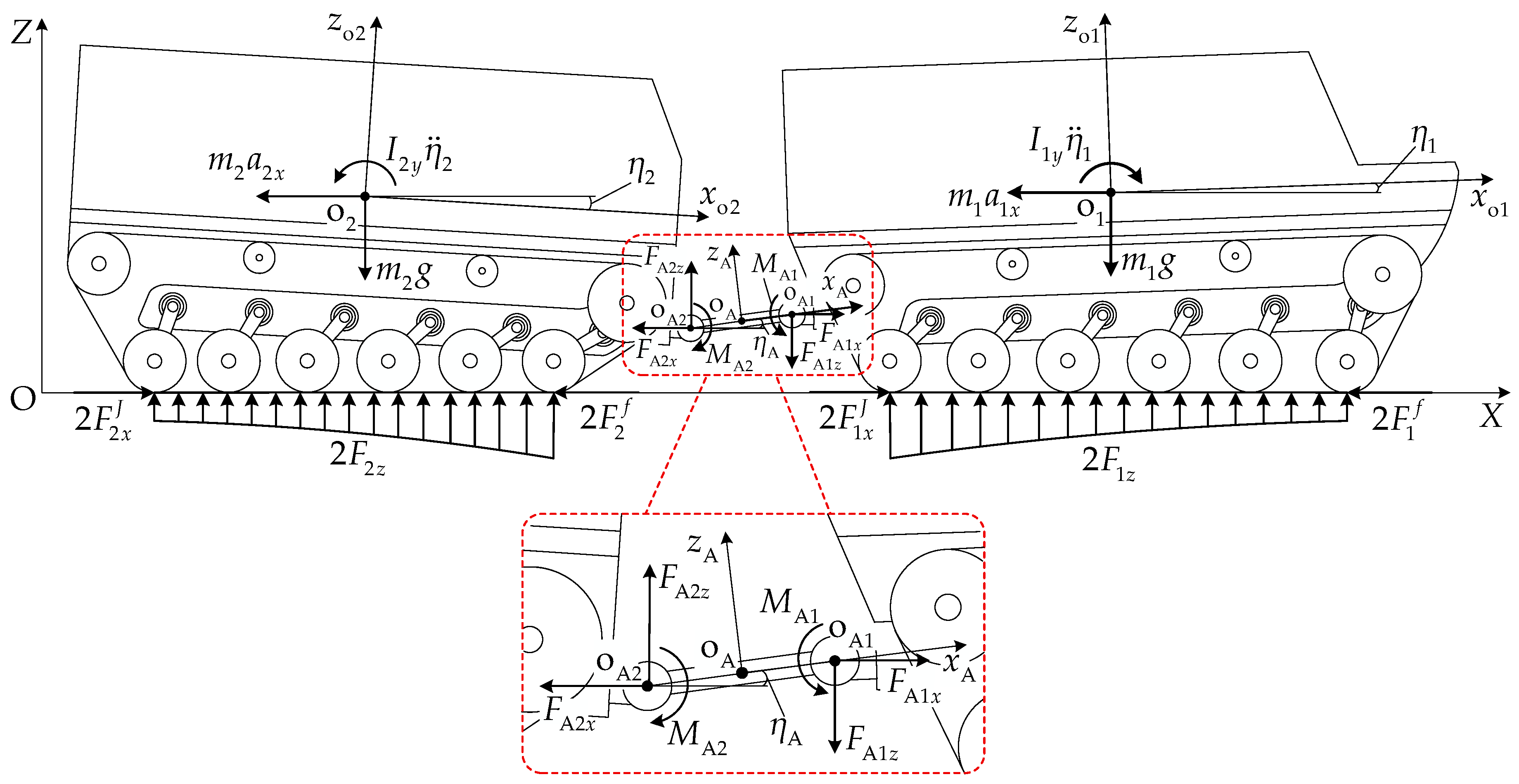

2. Kinematic Model of Pitch Motion

2.1. Vehicle Structure and Biomimetic Correspondence Analysis

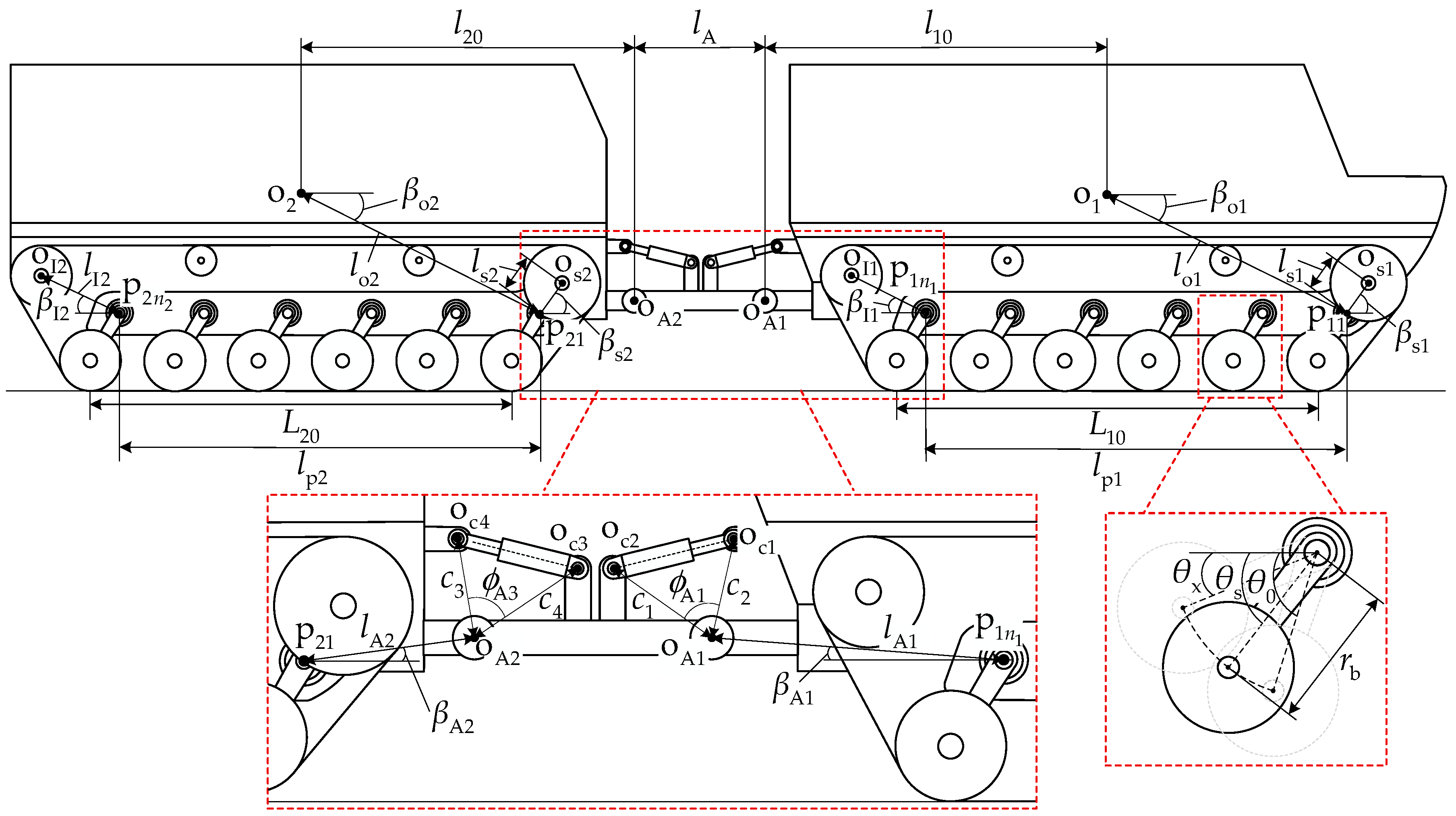

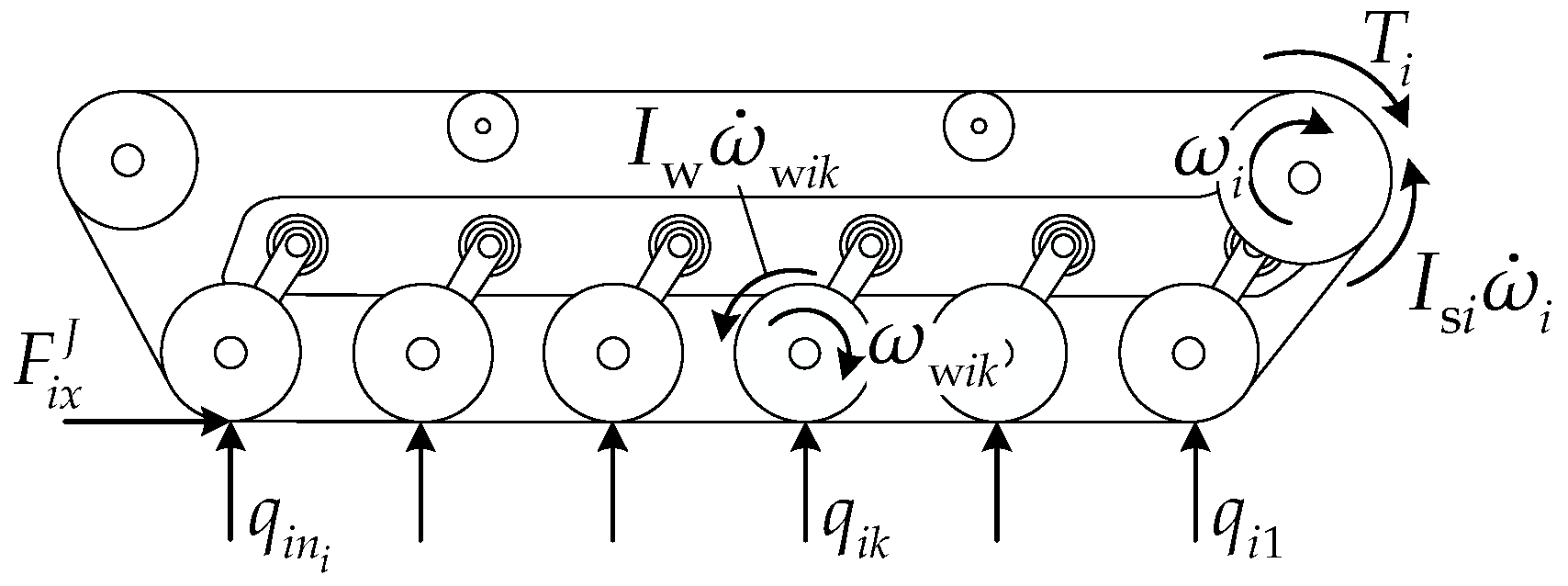

2.1.1. Torsion Bar Suspension System

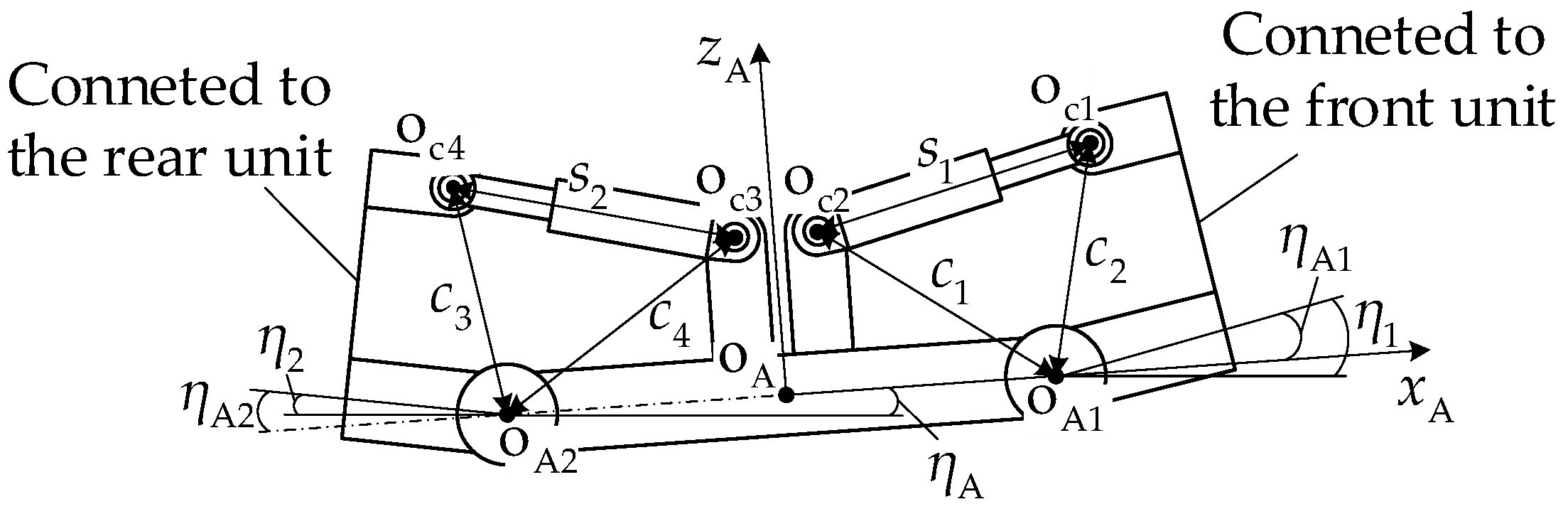

2.1.2. Pitch Mechanism

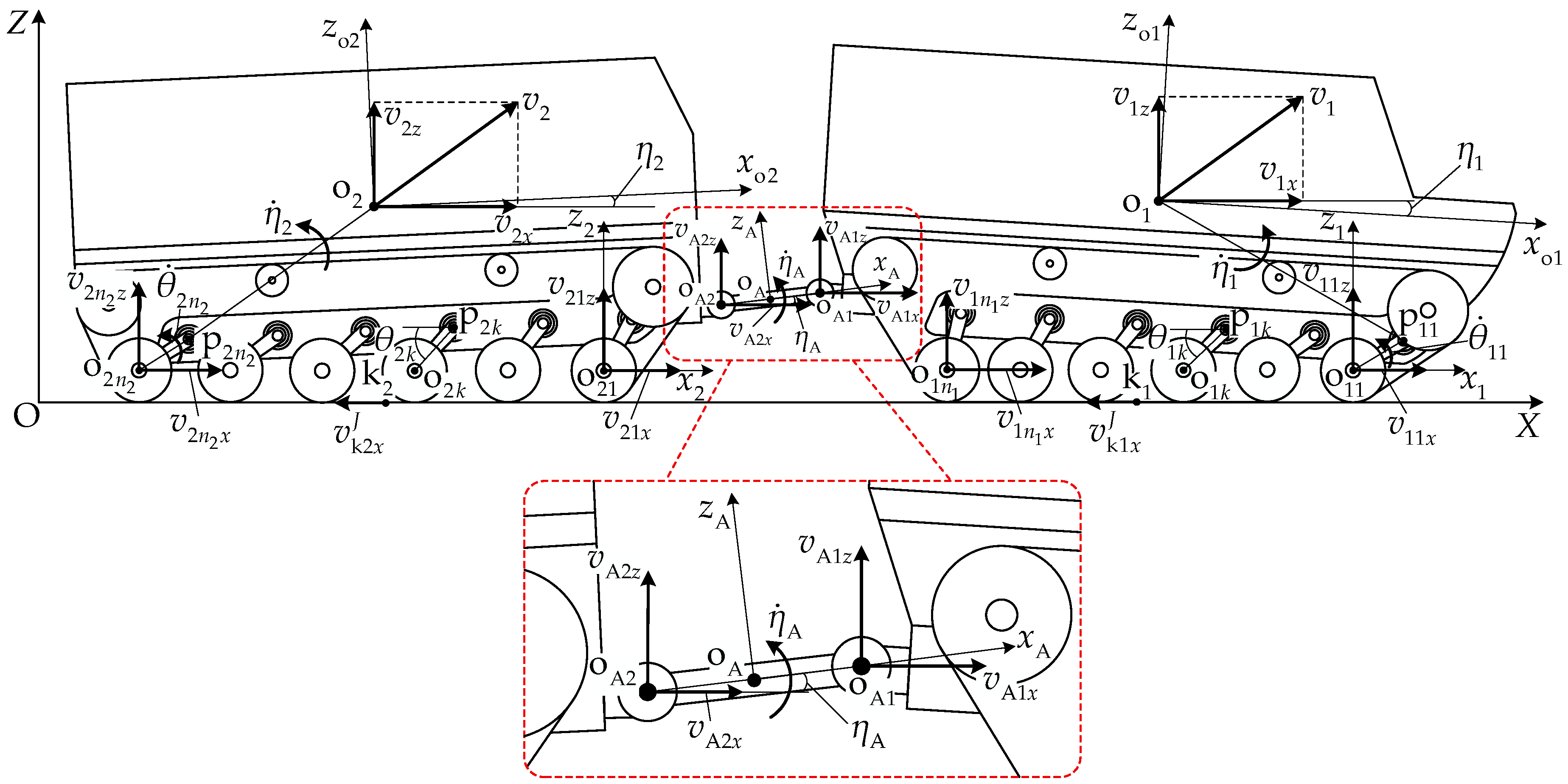

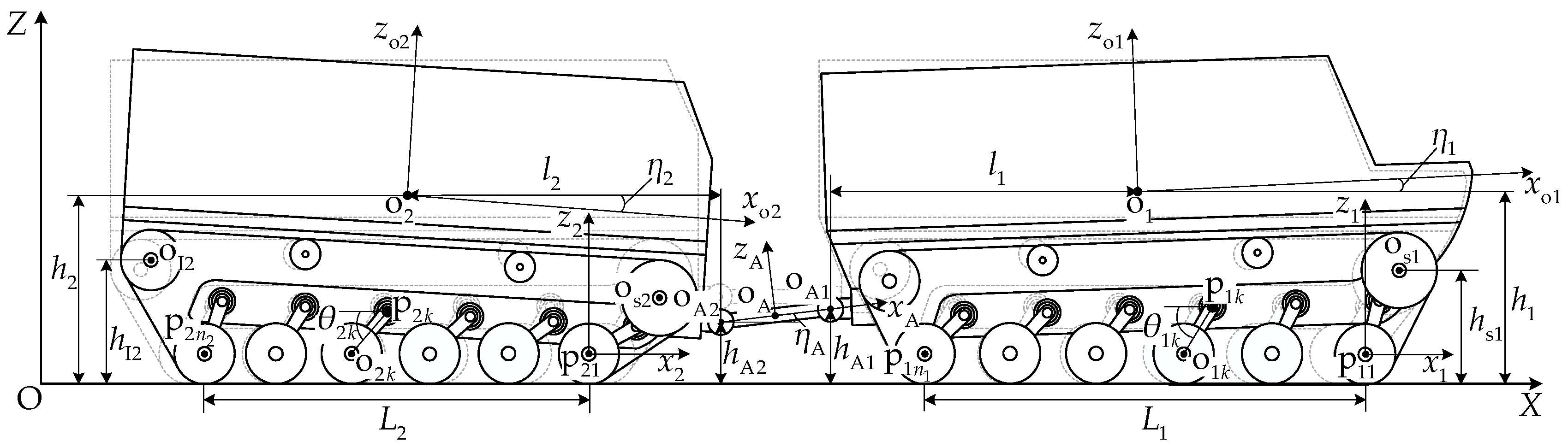

2.2. Coordinate System Definition and Geometric Relationships

2.3. Kinematic Constraint Equations

2.3.1. Unit Velocity Analysis

2.3.2. Velocity Constraint Relationships

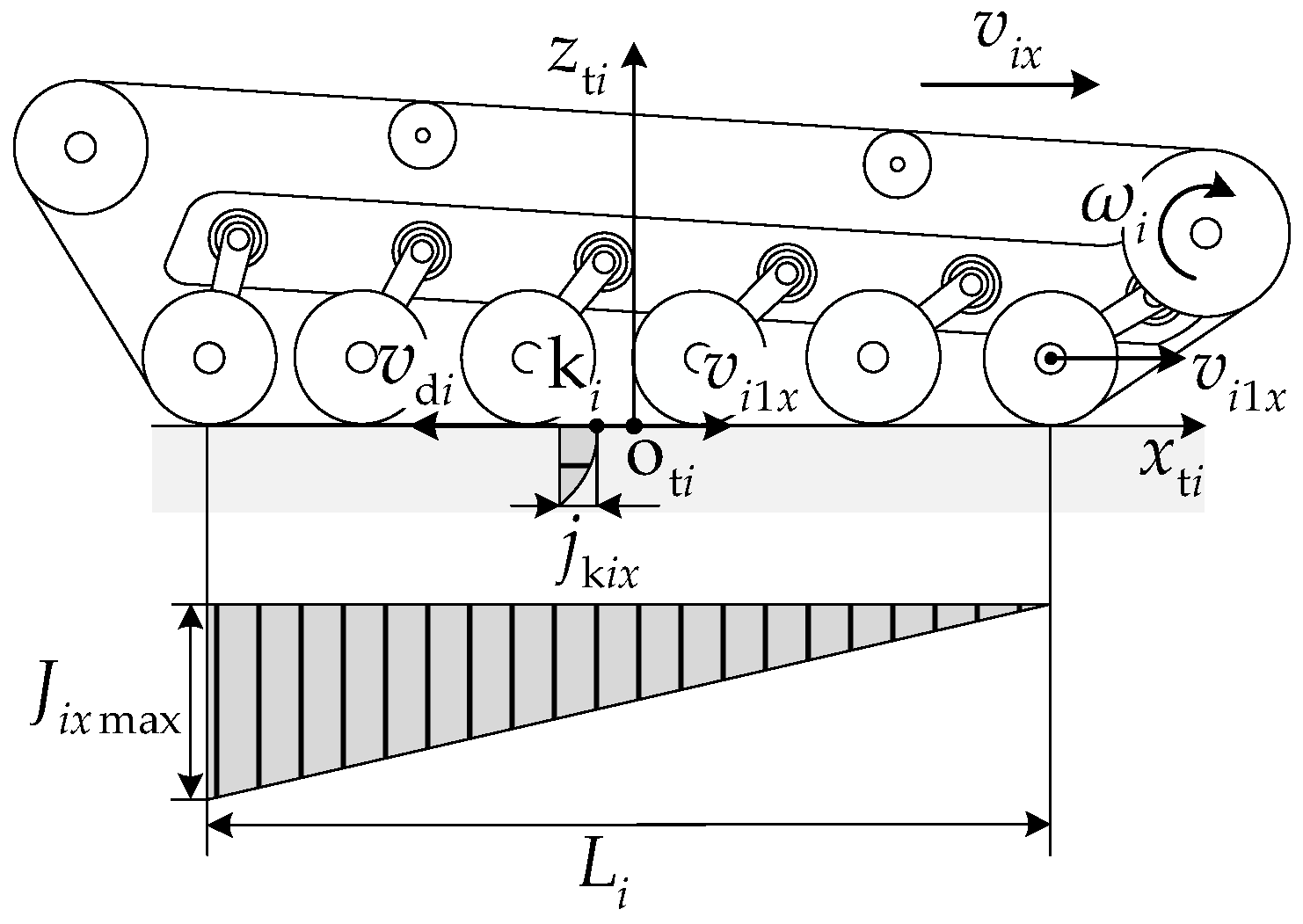

2.3.3. Track Motion Analysis

3. Pitch Motion Dynamics Modeling

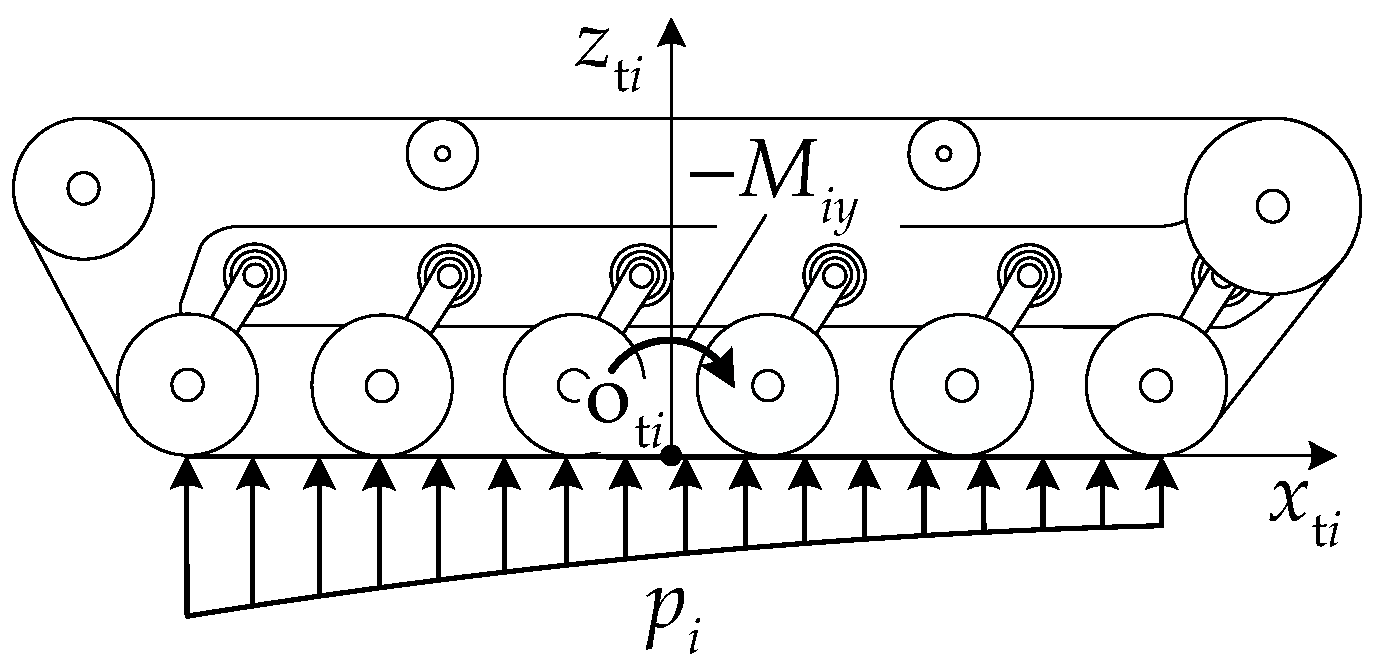

3.1. Track–Terrain Interaction

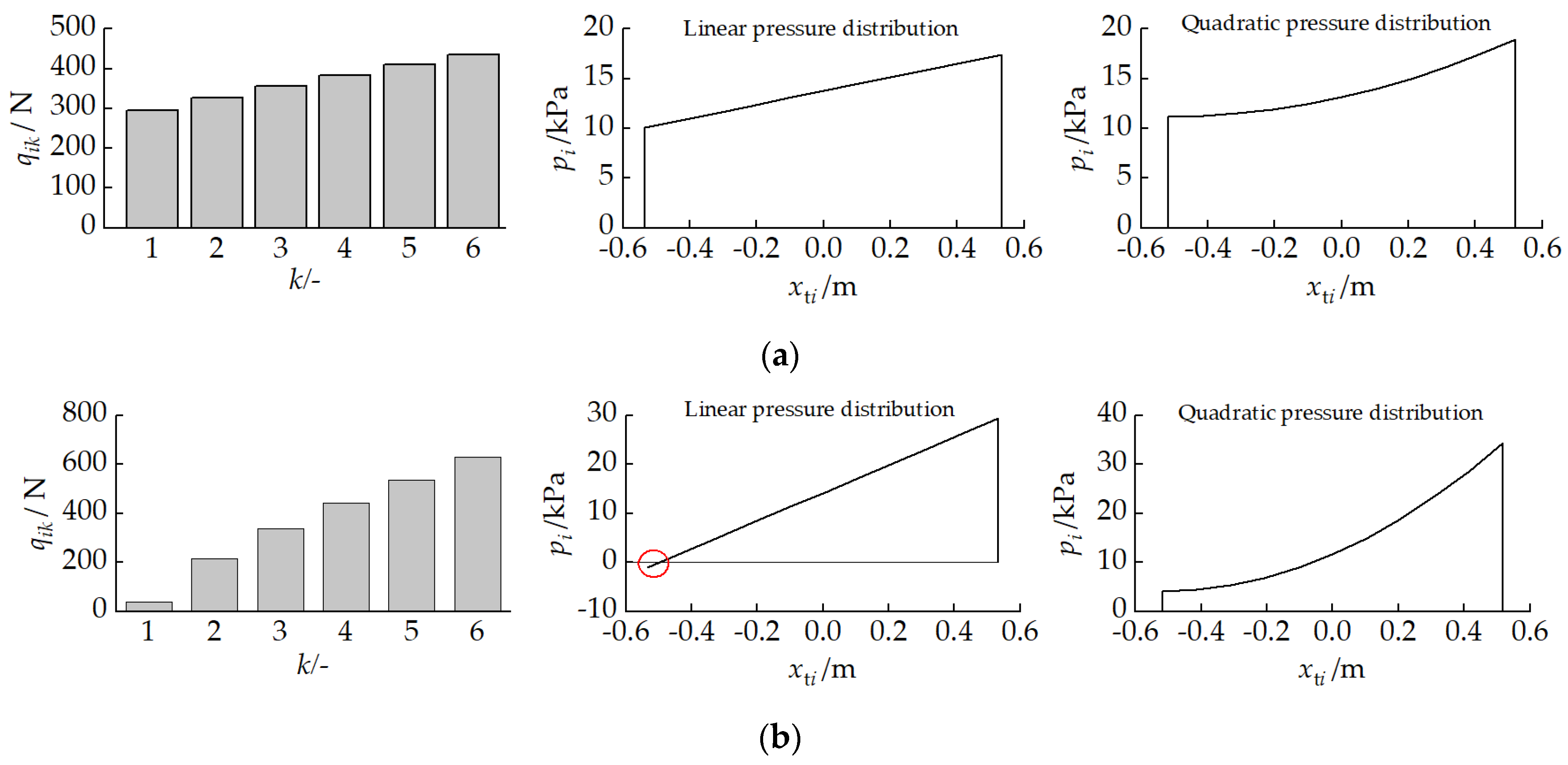

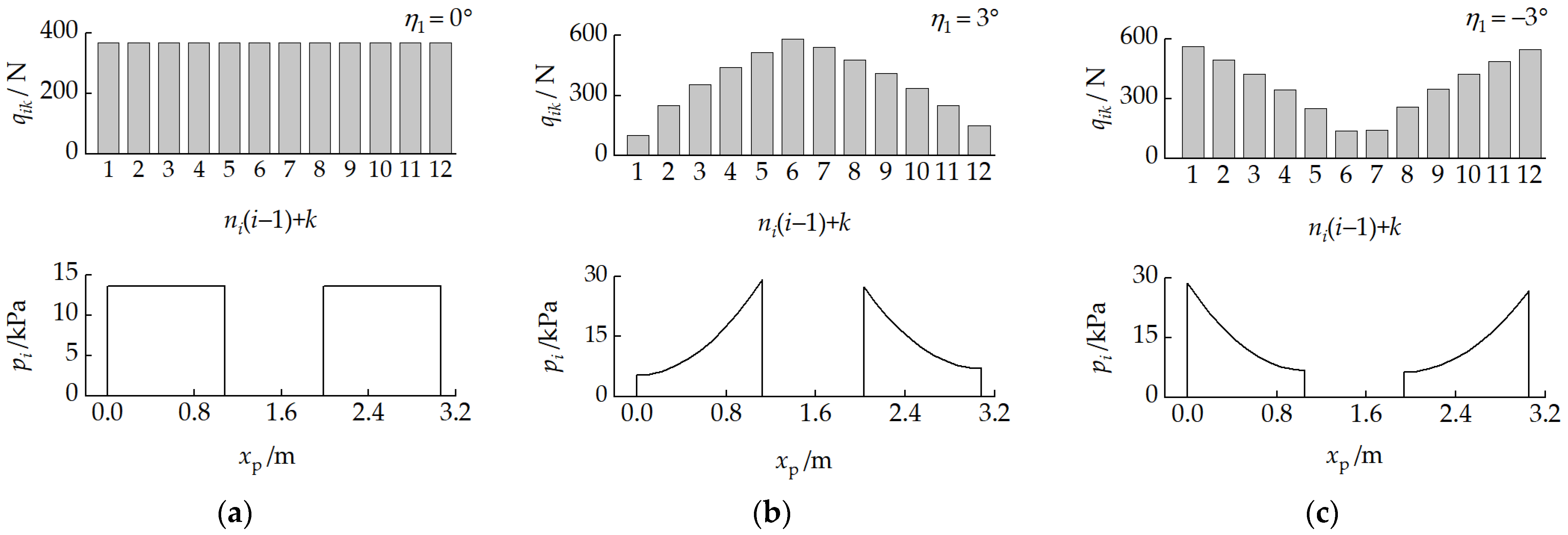

3.1.1. Road Wheel Load Distribution

3.1.2. Track–Ground Contact Pressure Distribution

- (1)

- The pressure is continuously distributed within the track–ground contact segment.

- (2)

- By neglecting the influence of the track width b, the normal pressure is uniformly distributed laterally and varies only along the track longitudinal direction.

3.1.3. Shear Displacement and Shear Force

3.2. Track System Driving Mechanics Modeling

3.2.1. Internal Rolling Resistance

3.2.2. External Motion Resistance

3.2.3. Drive Mode

3.3. Pitch Dynamics Equations

4. Numerical Calculation and Results Analysis

4.1. Vehicle Parameters

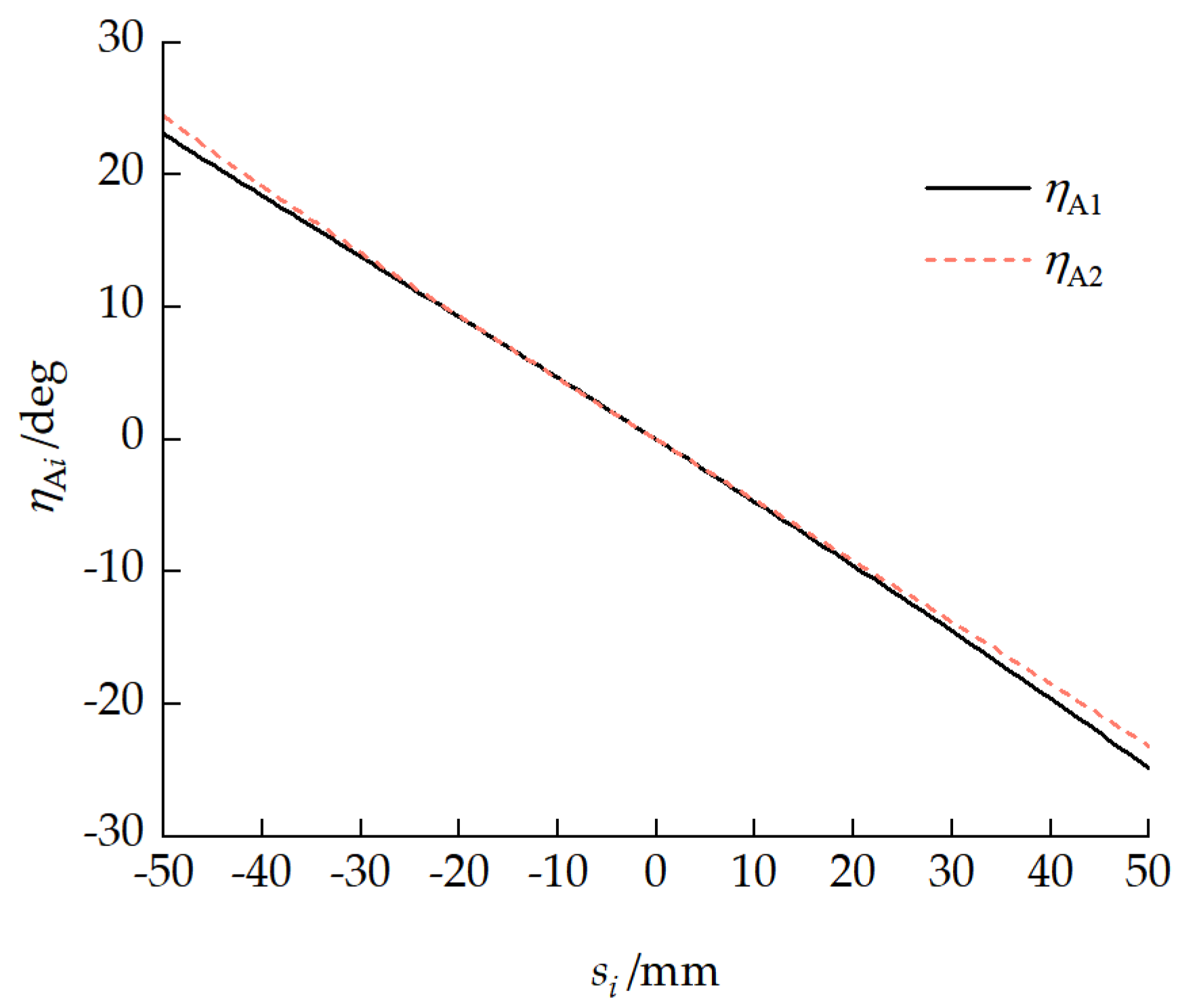

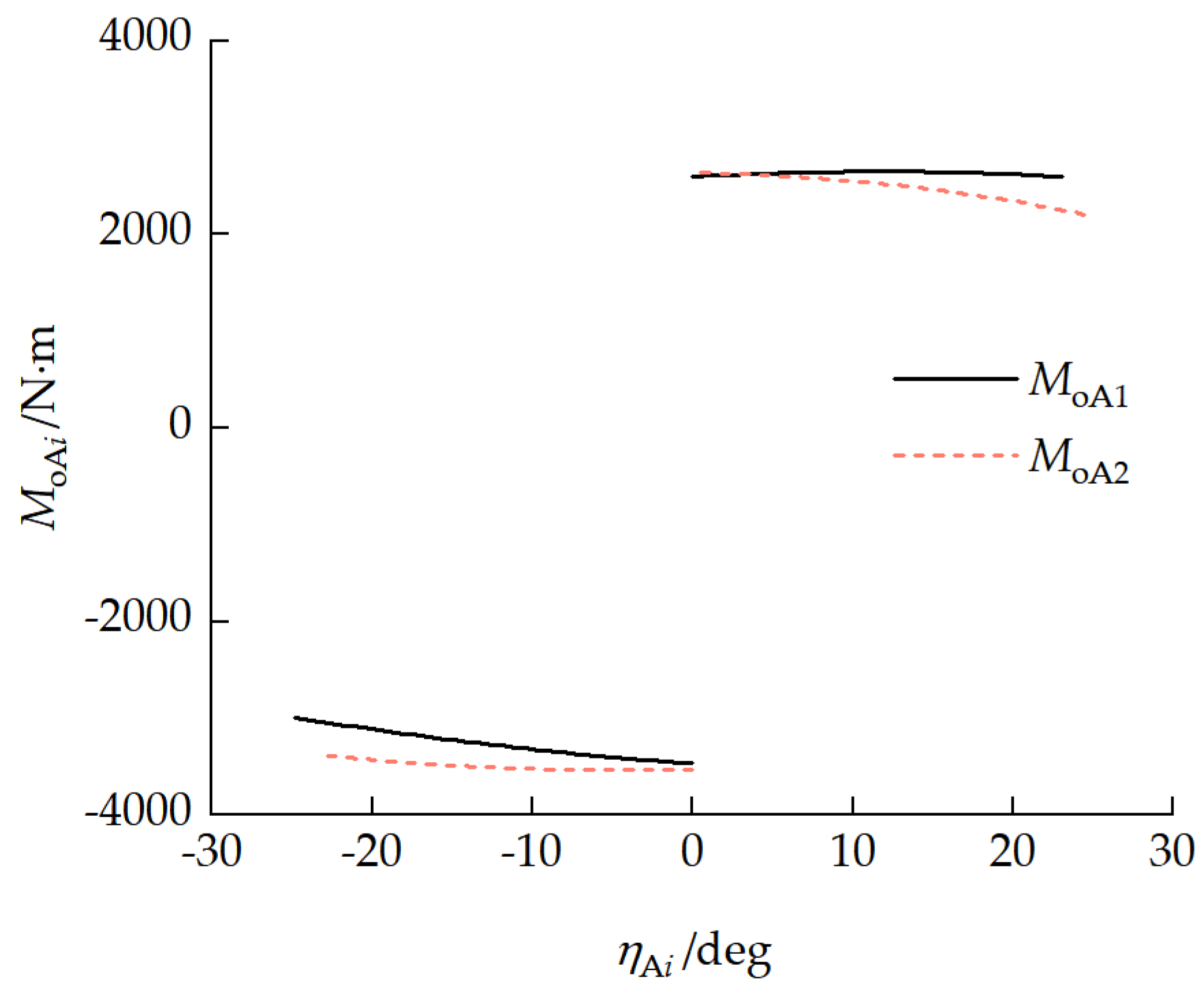

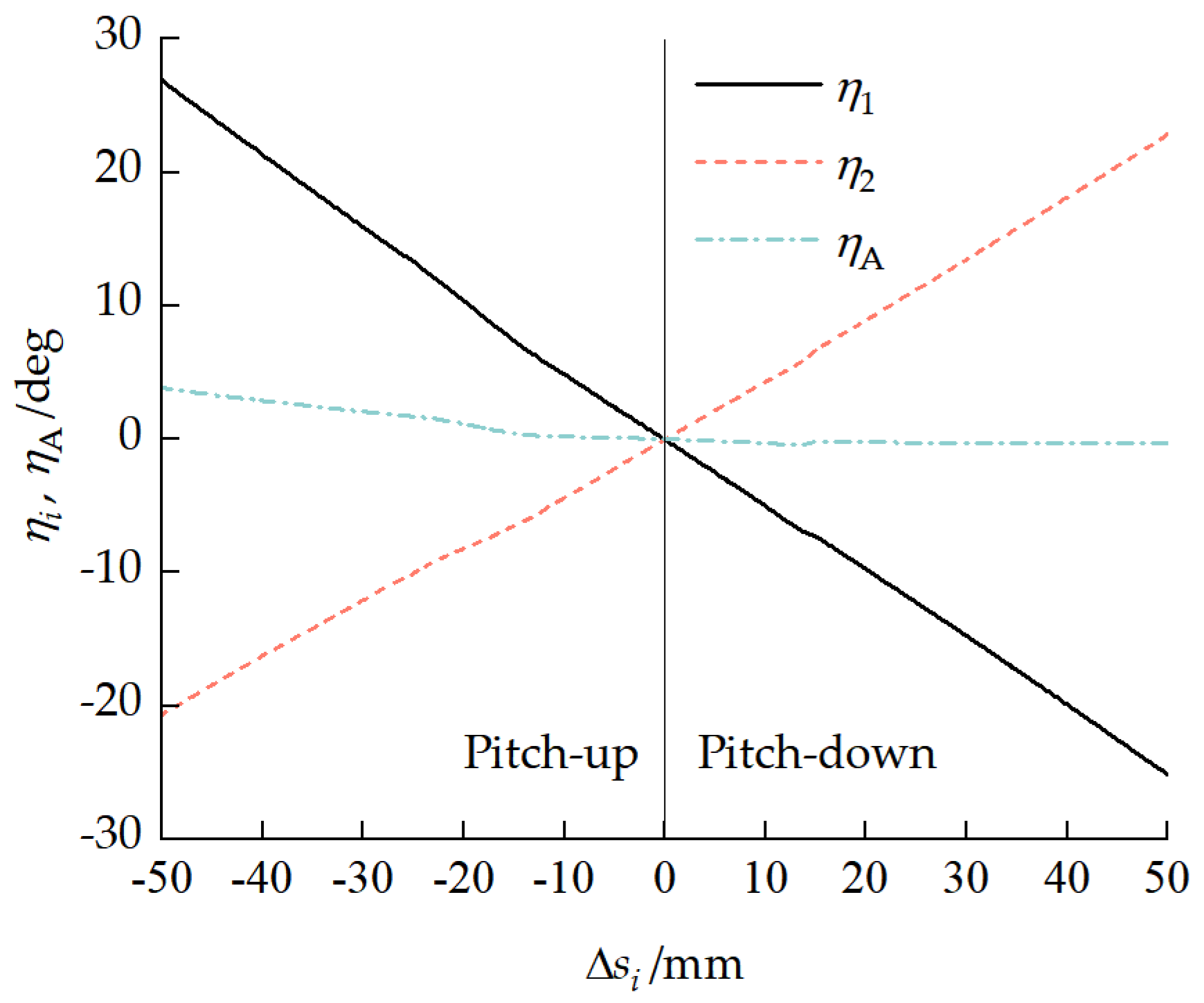

4.2. Pitch Mechanism Characteristic Analysis

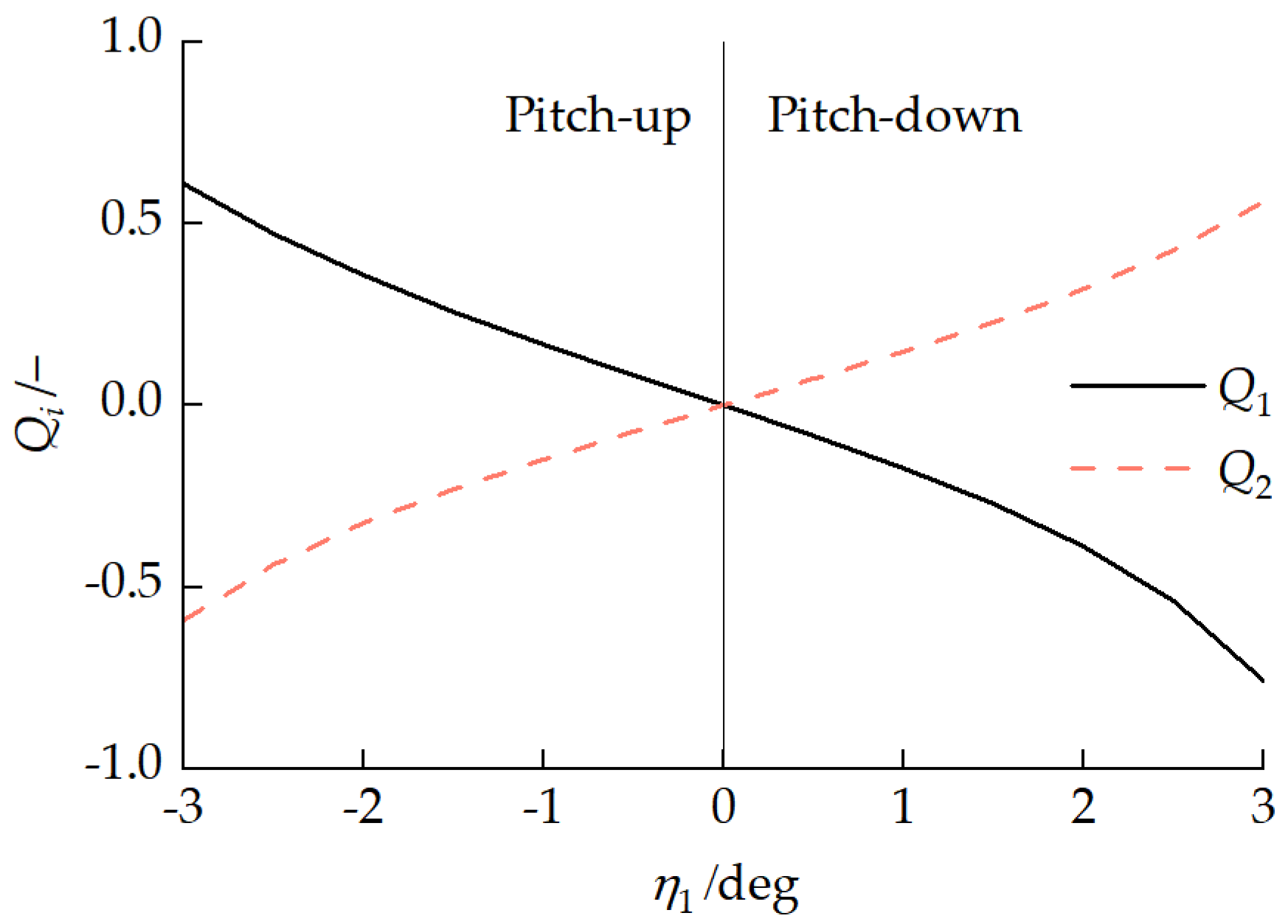

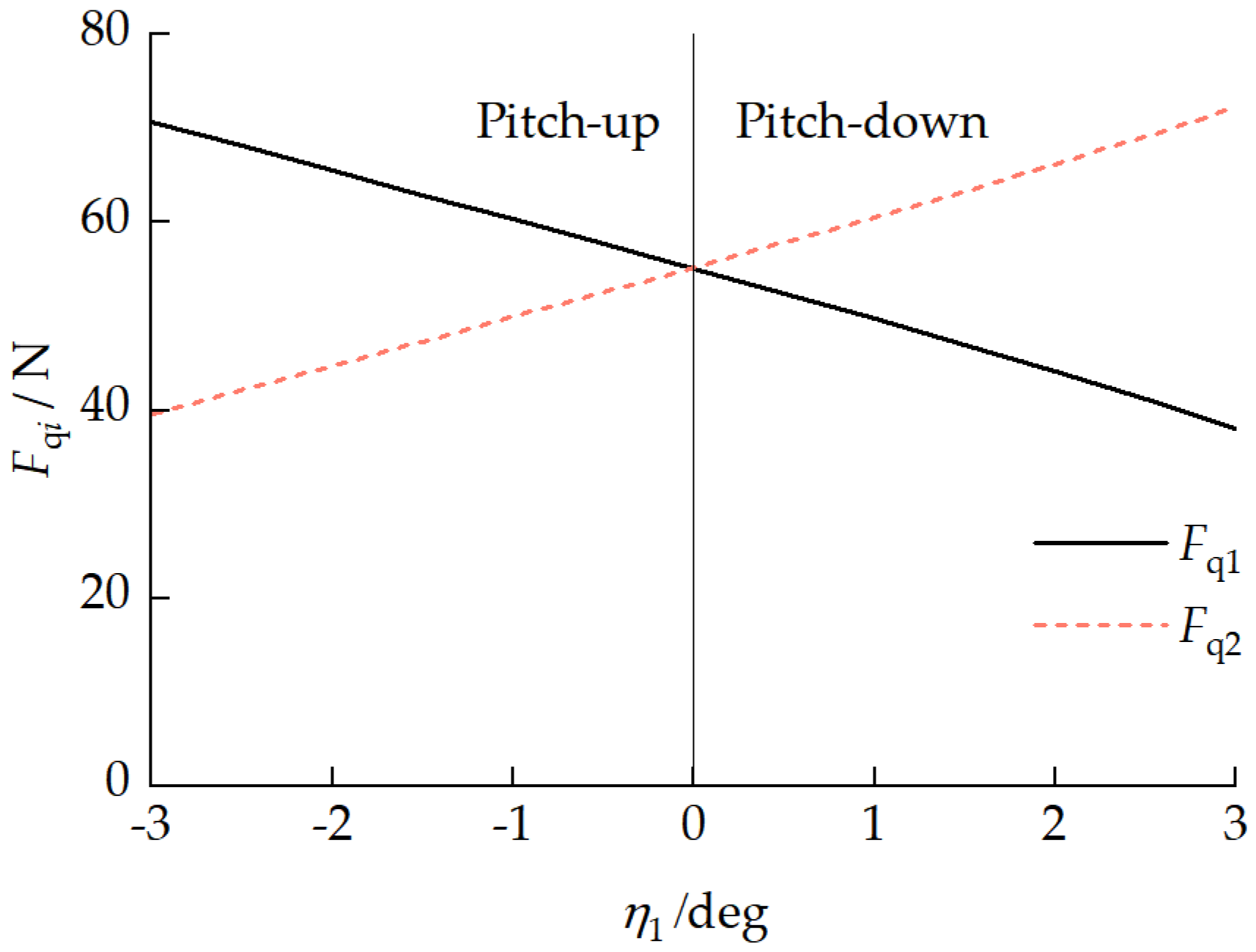

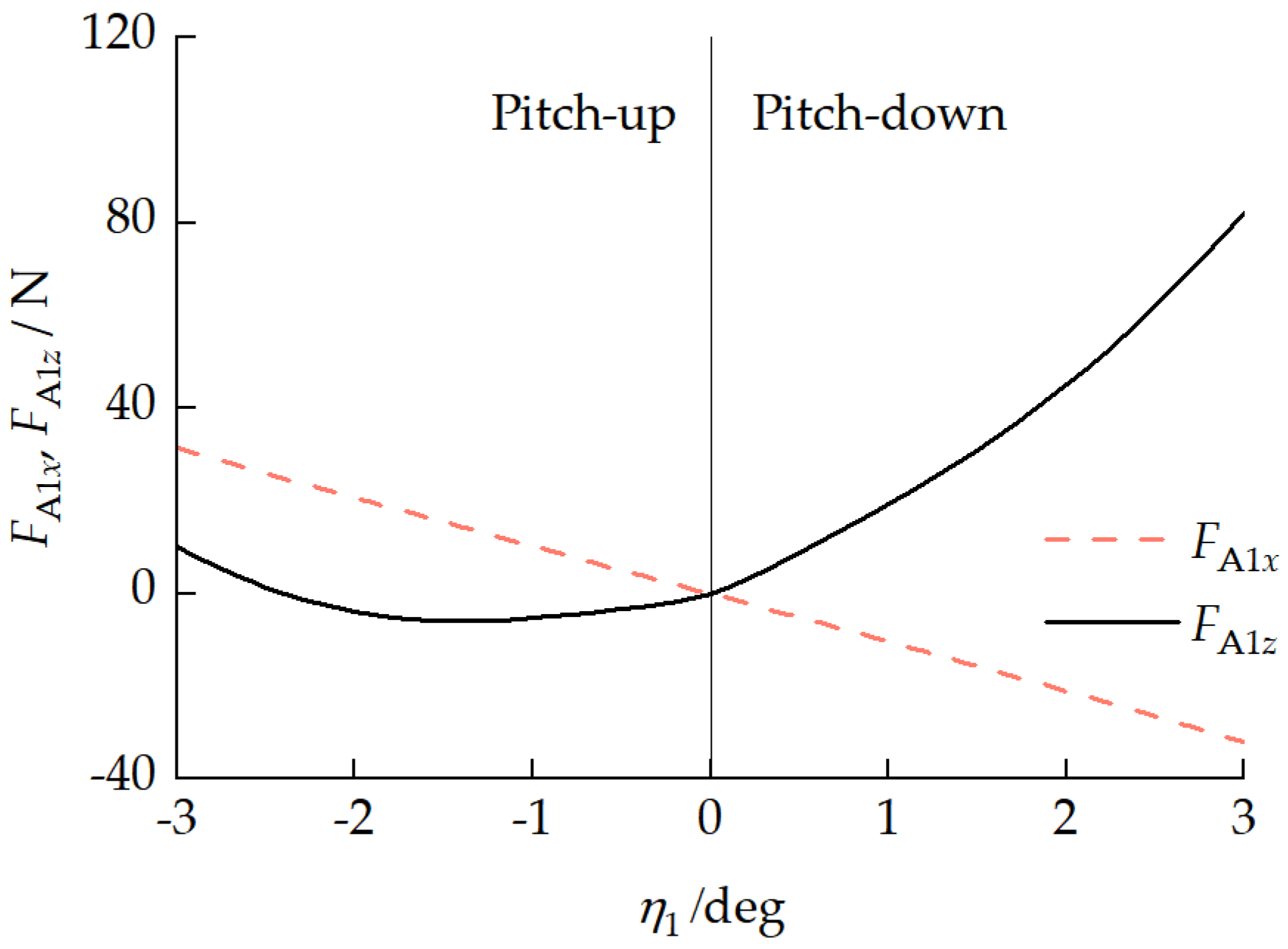

4.3. Static-Pitch-Attitude Adjustment Analysis

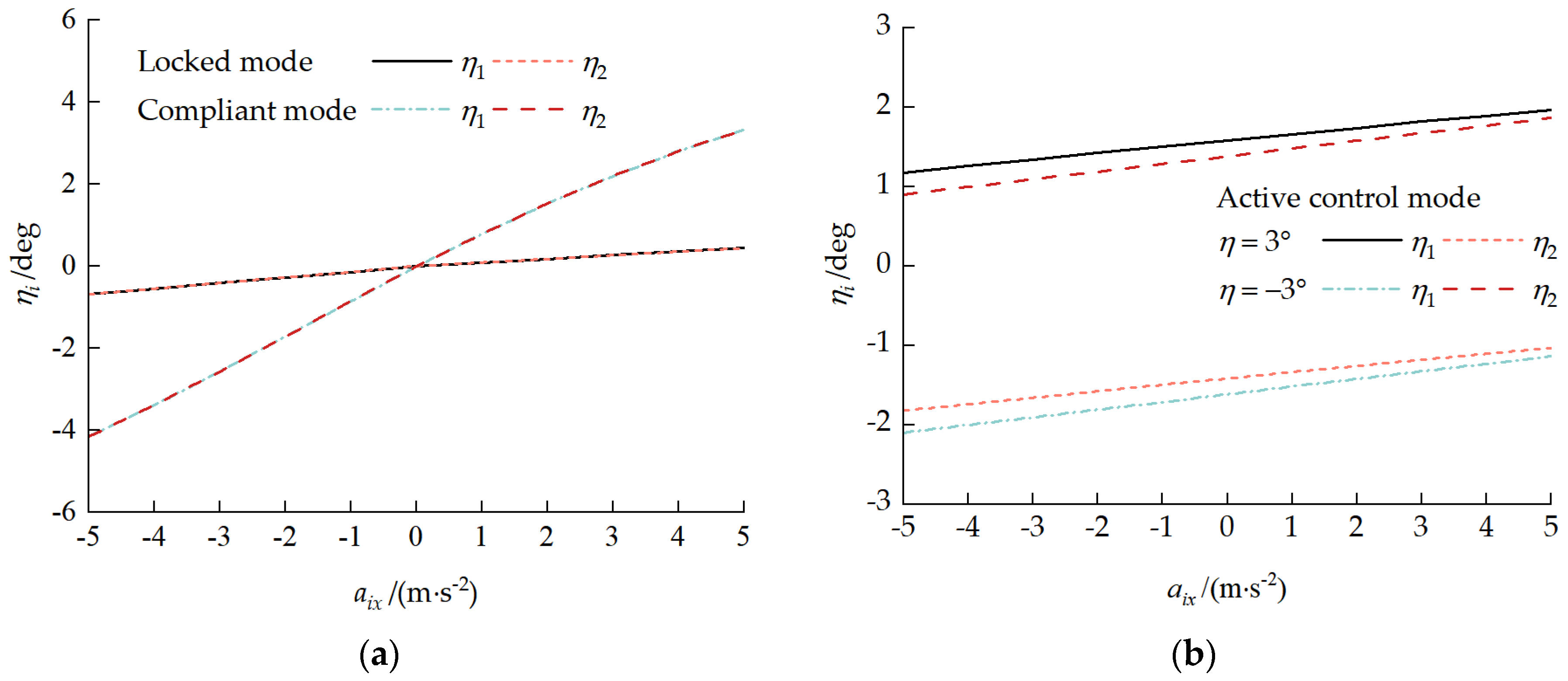

4.3.1. Vehicle Pitch Attitude Characteristics

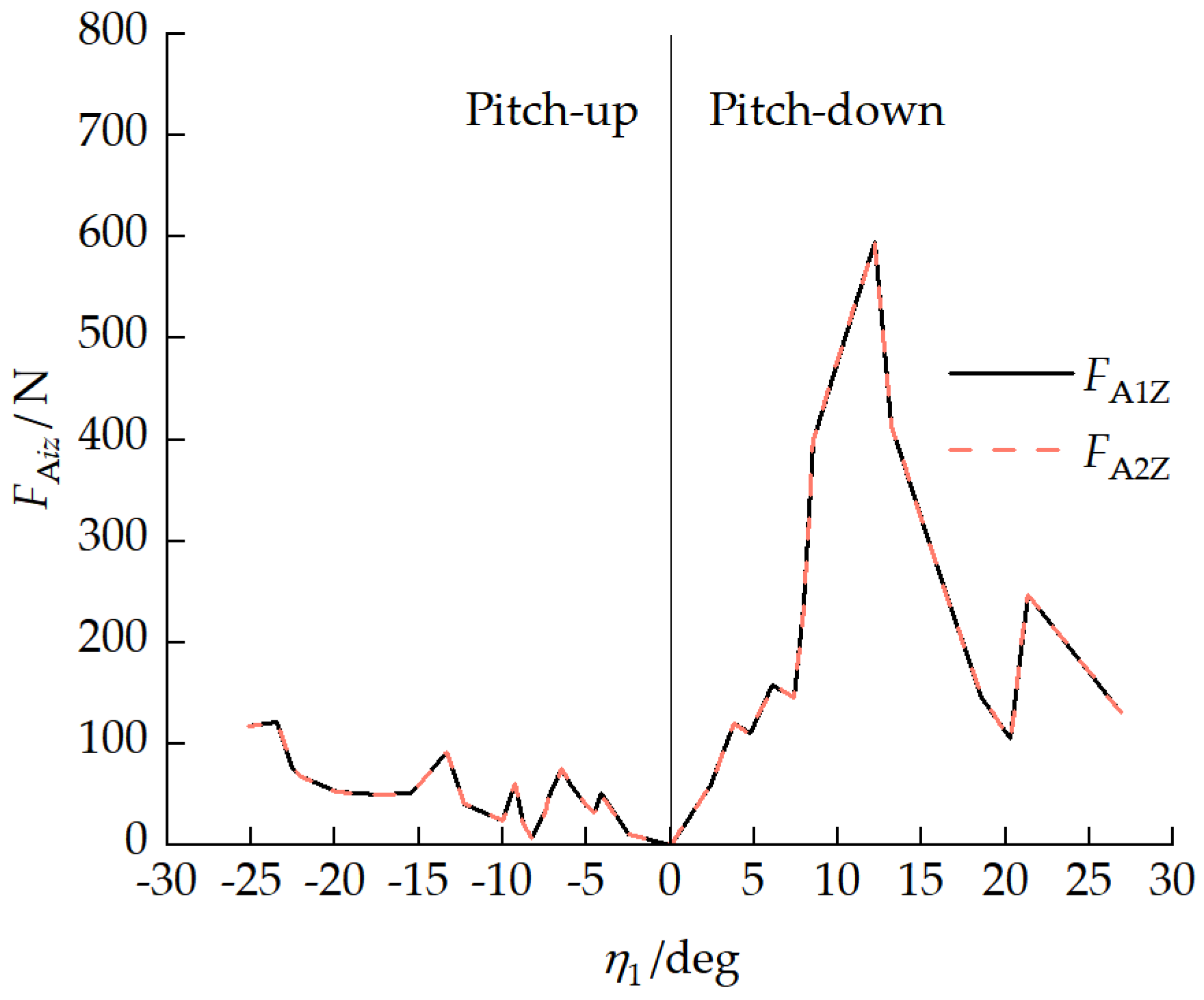

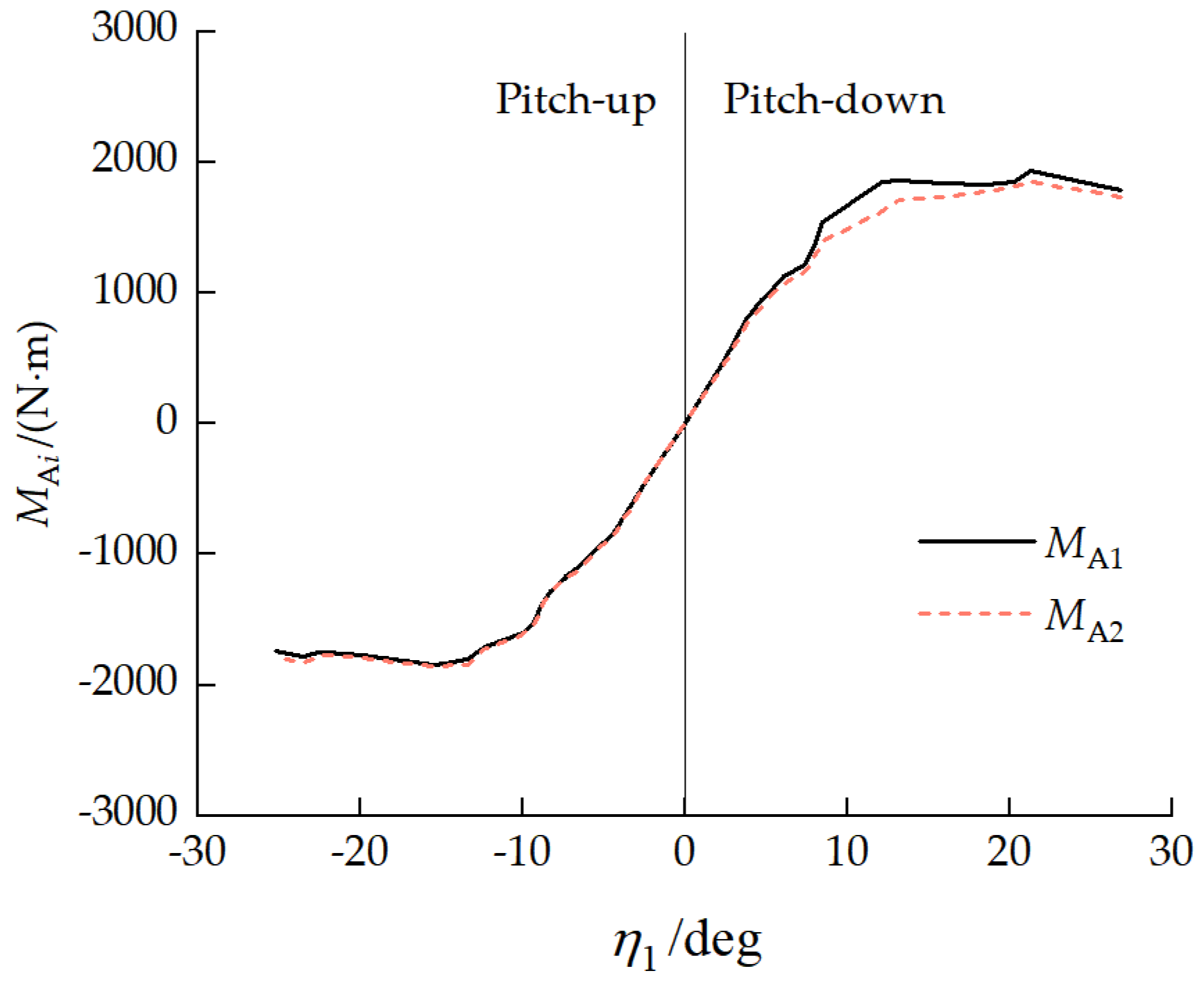

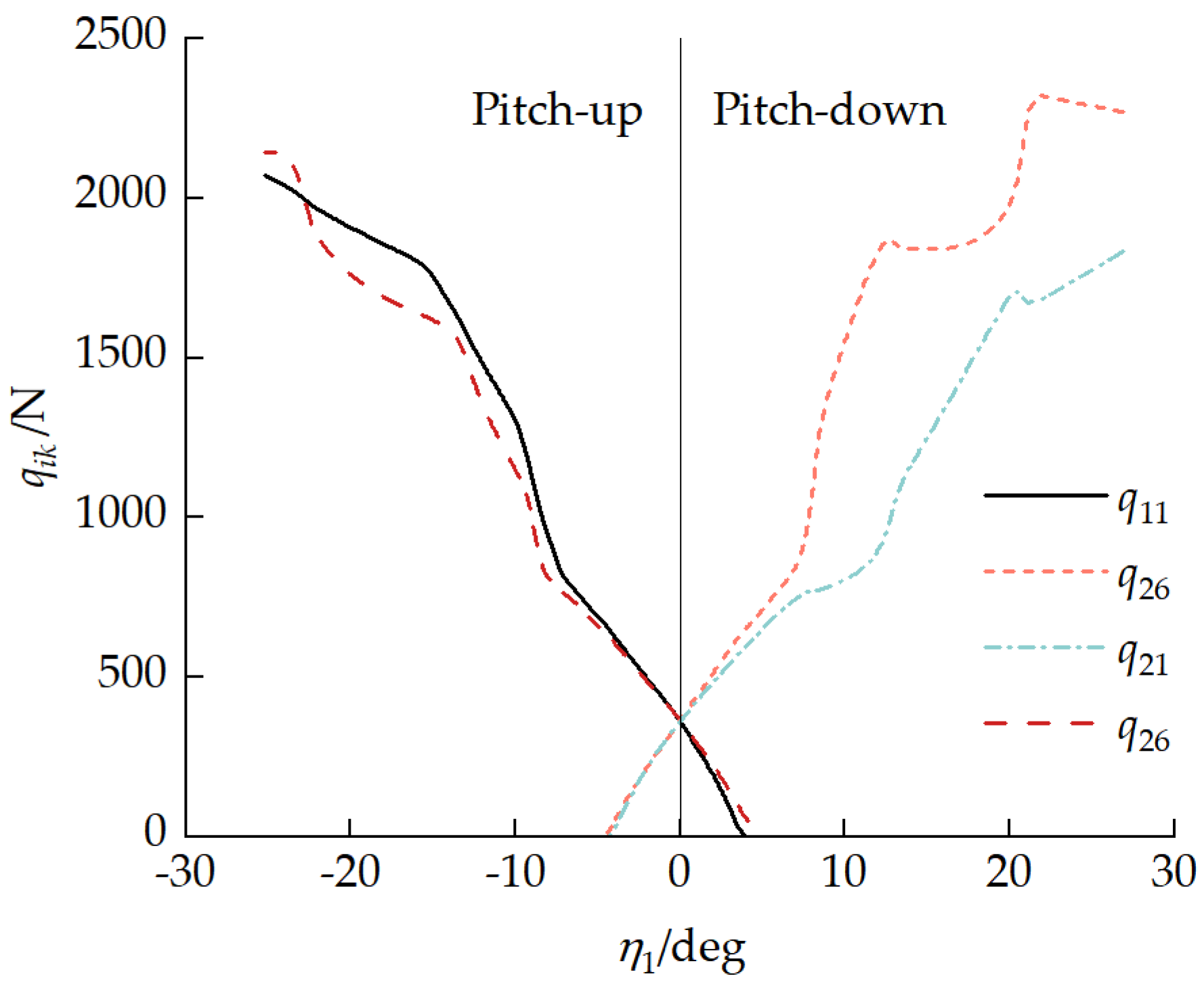

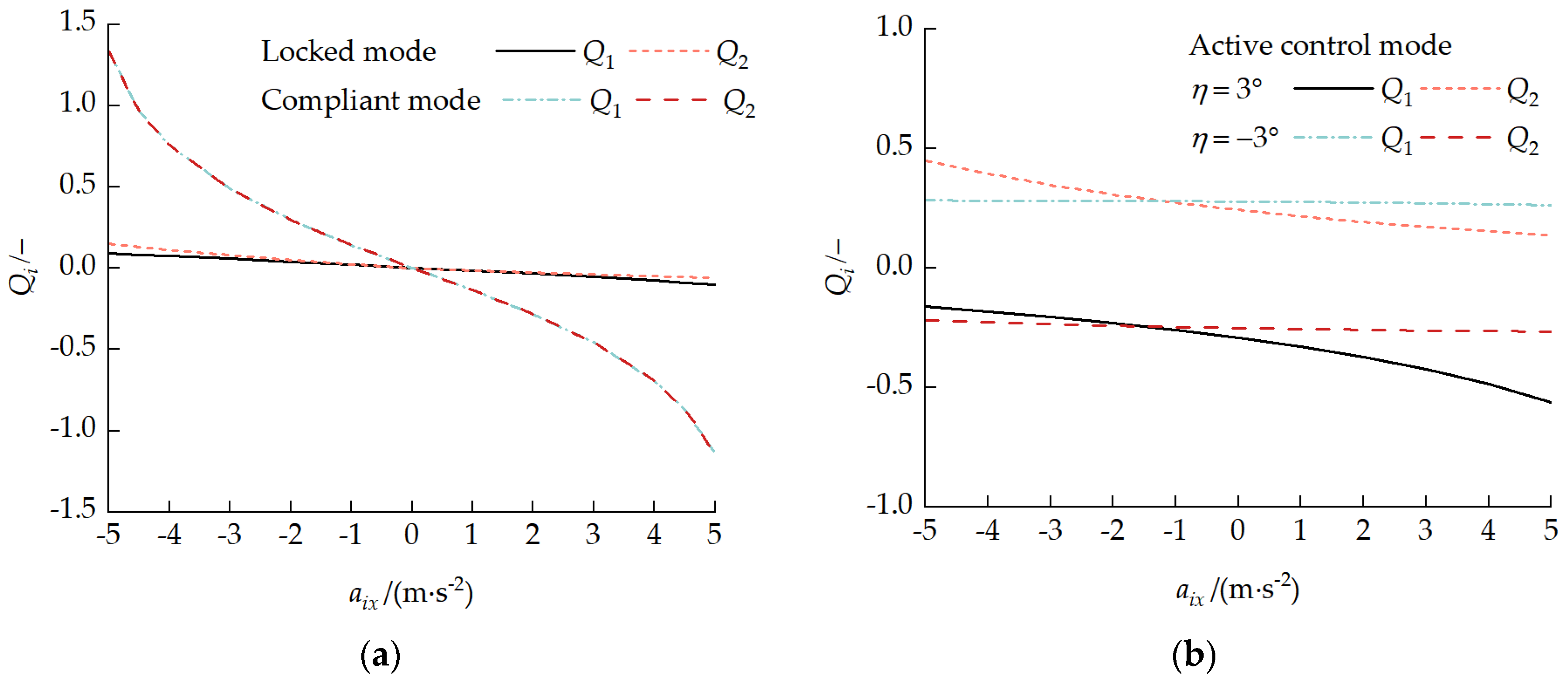

4.3.2. Inter-Unit Coupling Forces

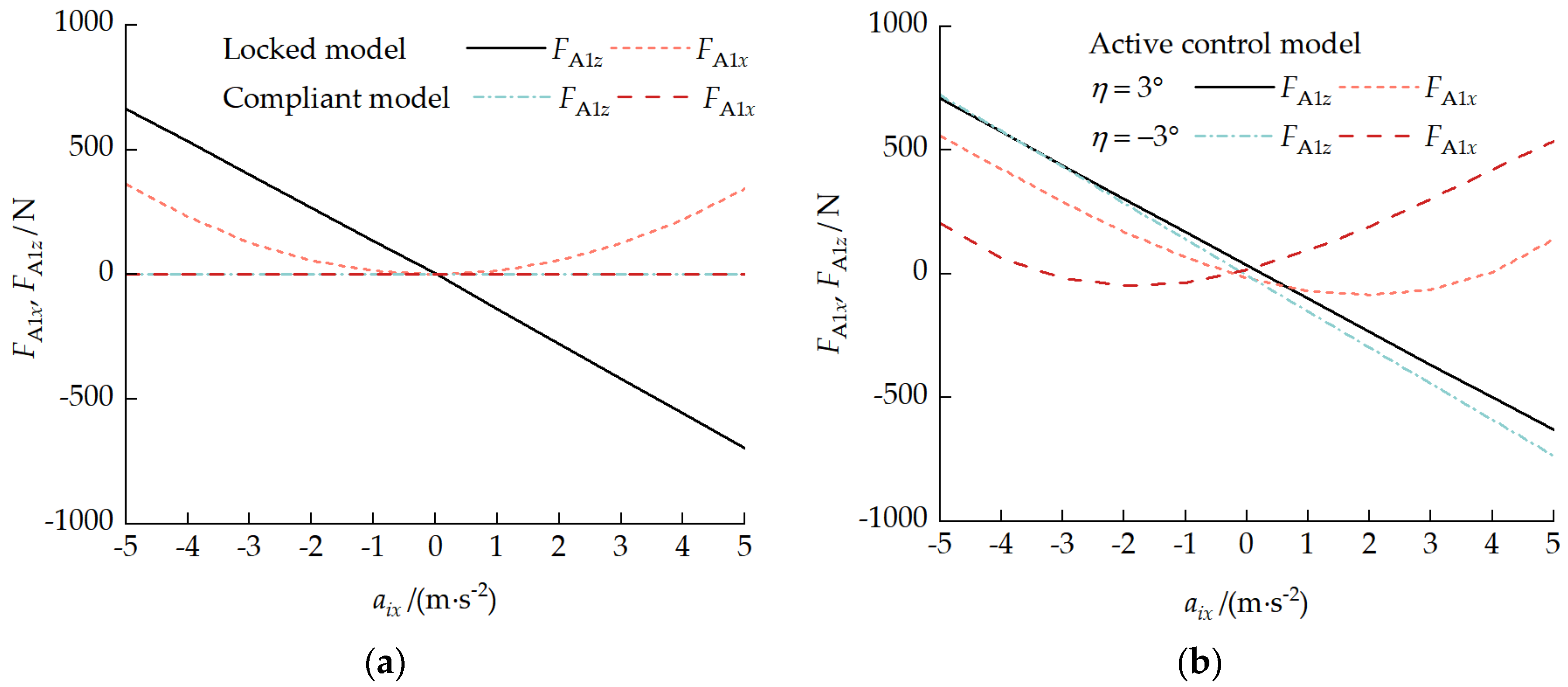

4.3.3. Ground Contact Characteristic Analysis

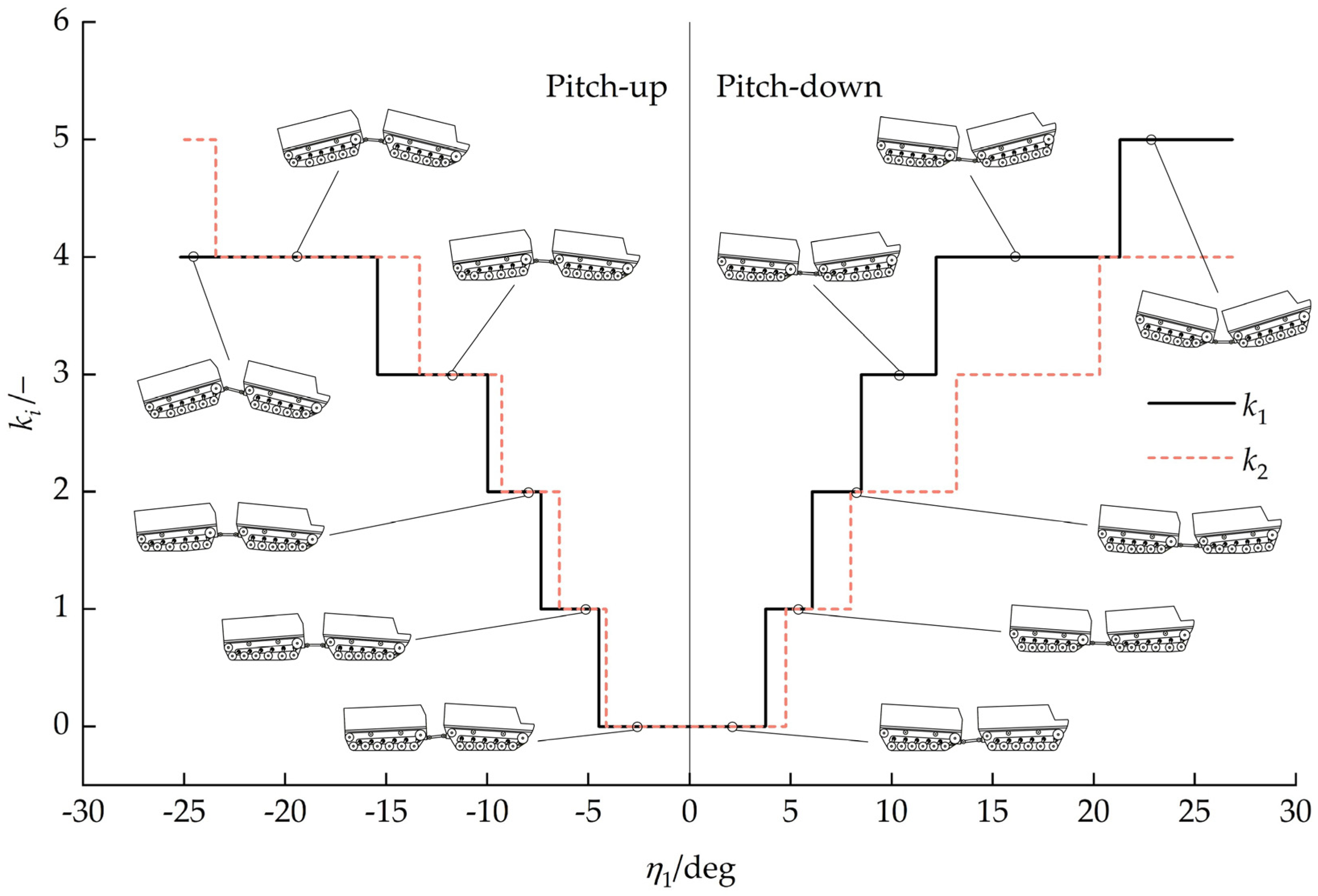

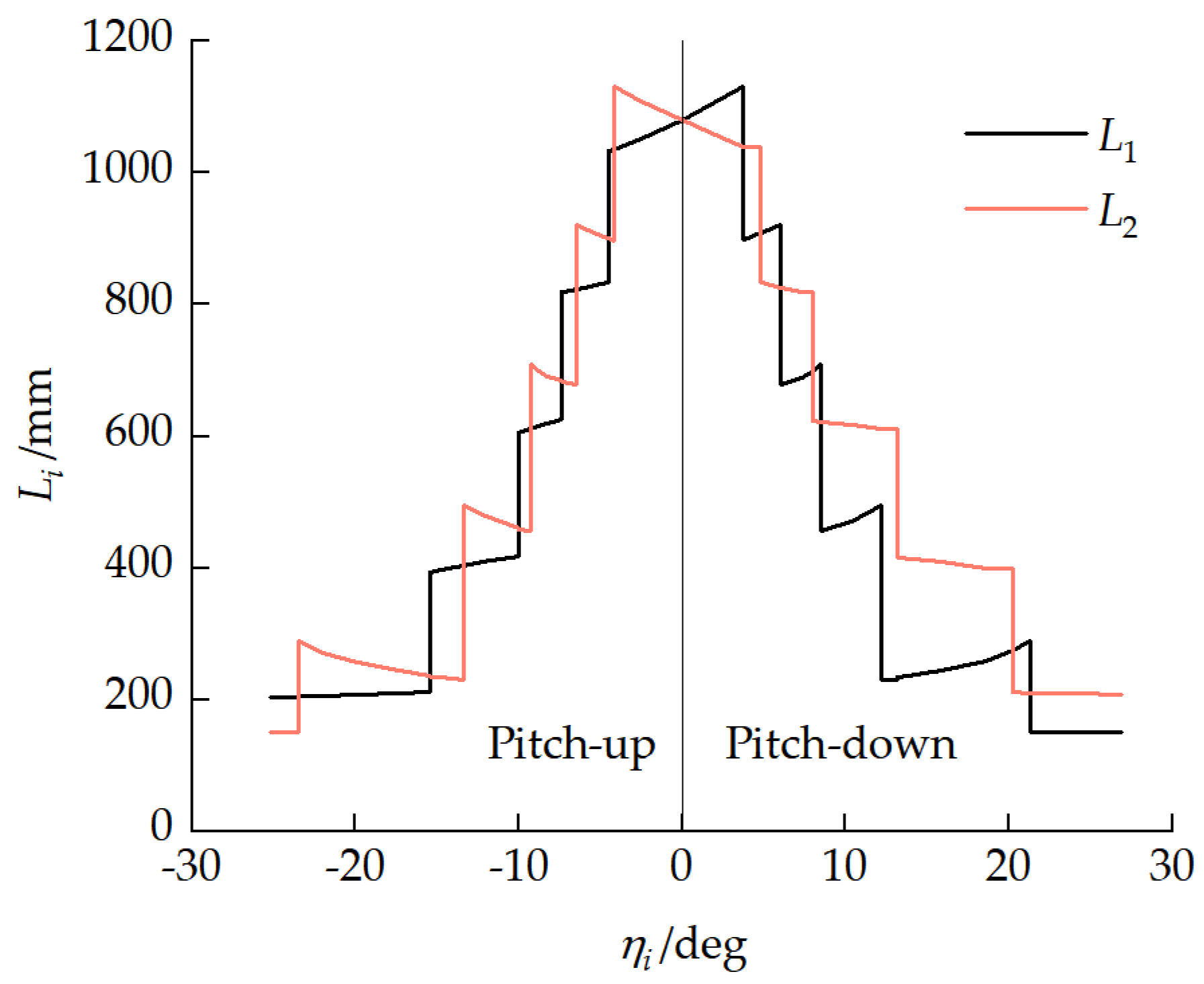

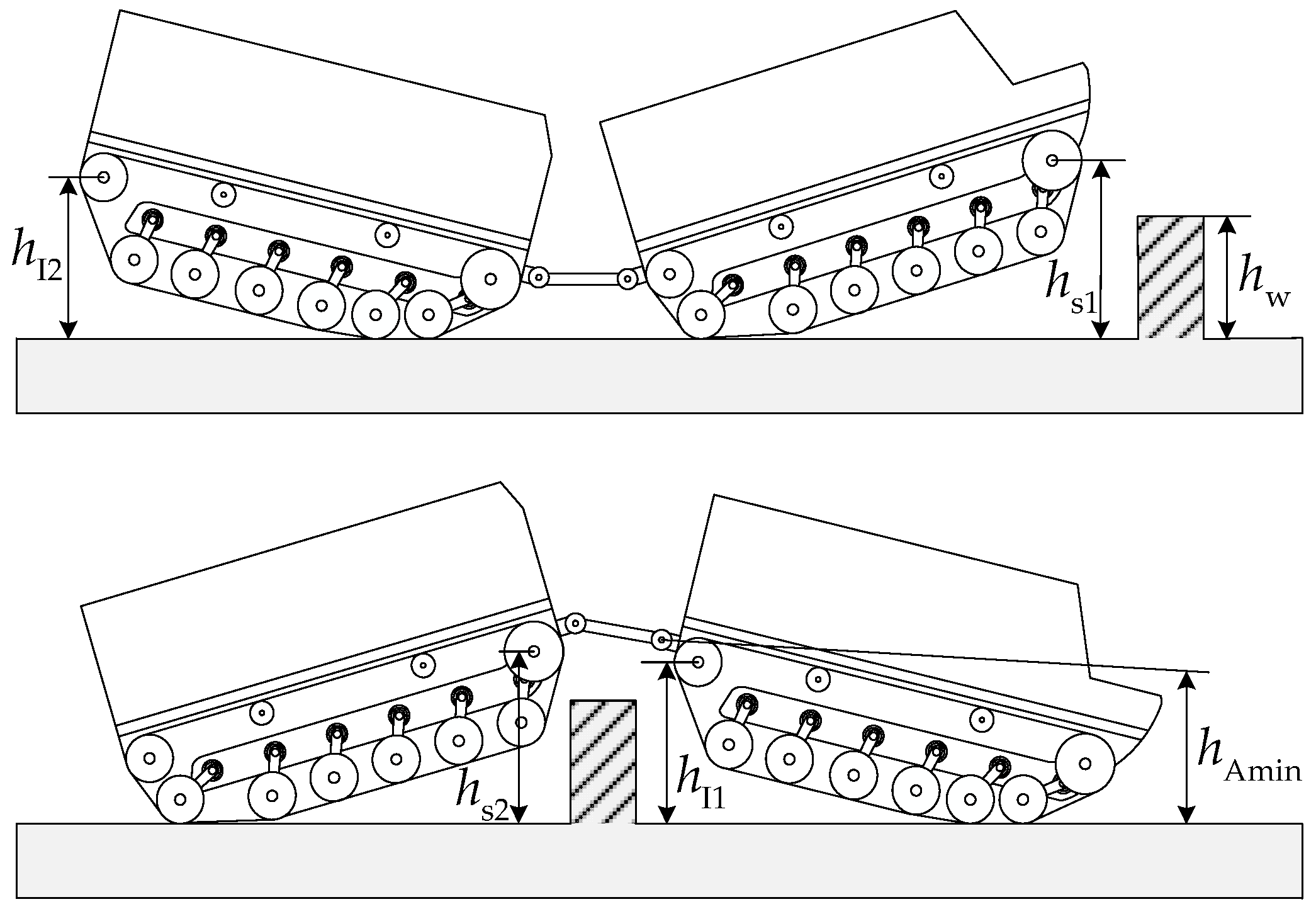

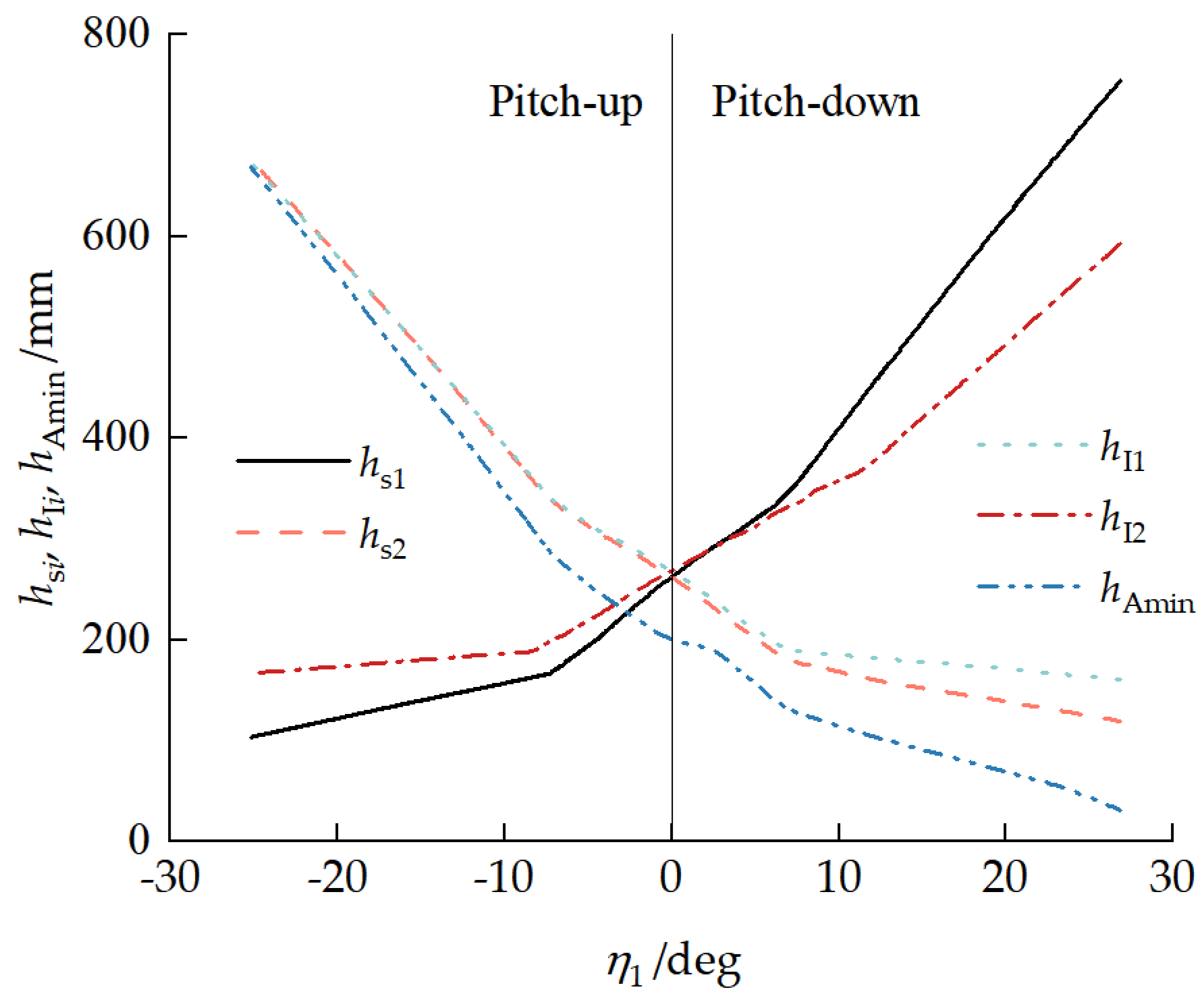

4.3.4. Obstacle-Crossing Capability Analysis

4.3.5. Sensitivity Analysis of Suspension Articulation Torsional Stiffness

5. Vehicle Driving Characteristics and Cooperative Obstacle-Crossing

- (1)

- Locked mode: The cylinder stroke does not change, and there is no pitch angle between the front and rear units. The units are equivalent to a rigidly connected four-track vehicle [49], with always.

- (2)

- Compliant mode: The cylinder stroke is in a free state. There is no constraint relationship between the front- and rear-unit pitch angles, with in this case.

- (3)

- Active control mode: The cylinder stroke is changed to cause the pitch mechanism to produce a pitch angle , thereby achieving the adjustment of the vehicle pitch angle . The front- and rear-unit pitch angles satisfy , and the pitch mechanism moments satisfy .

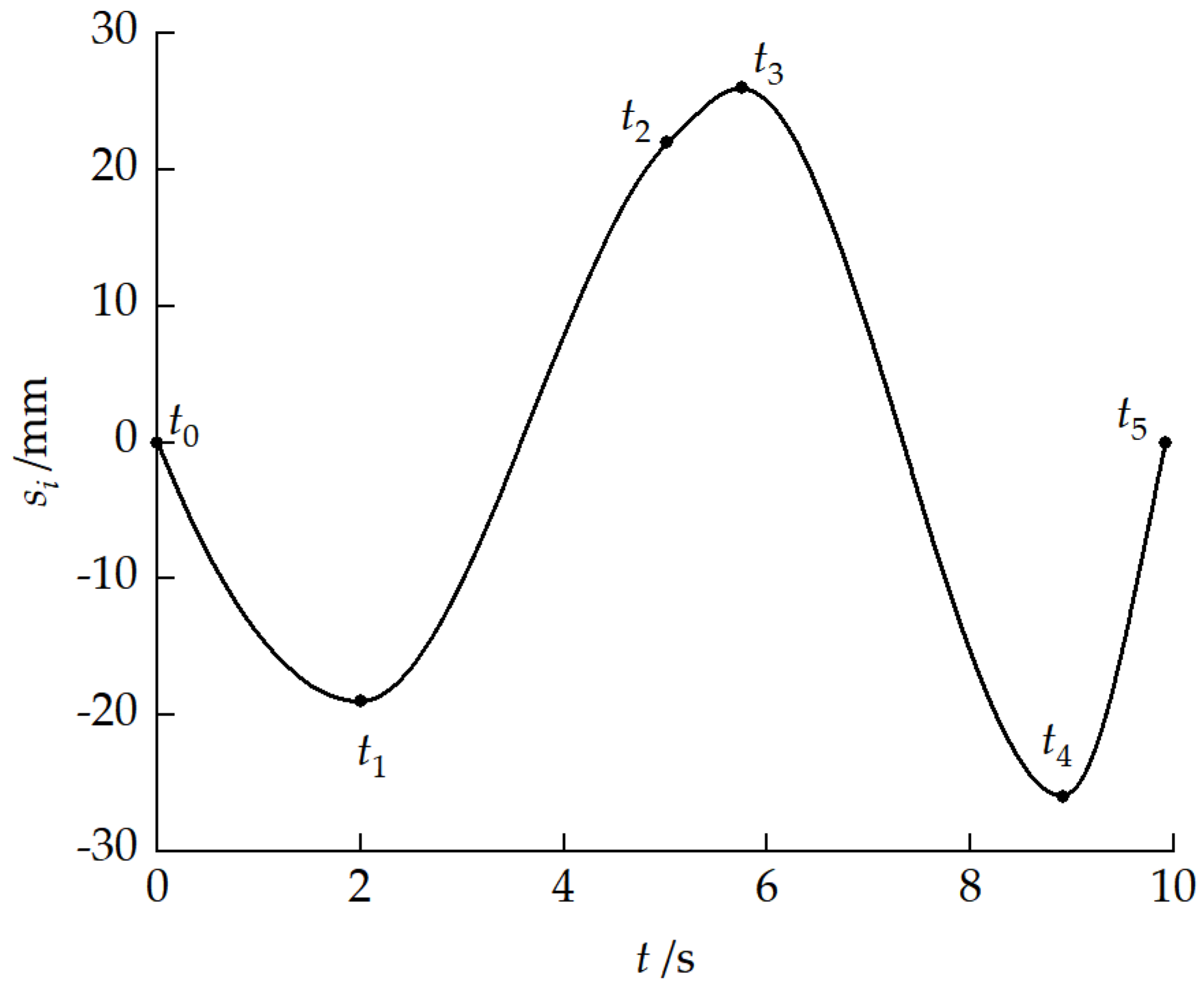

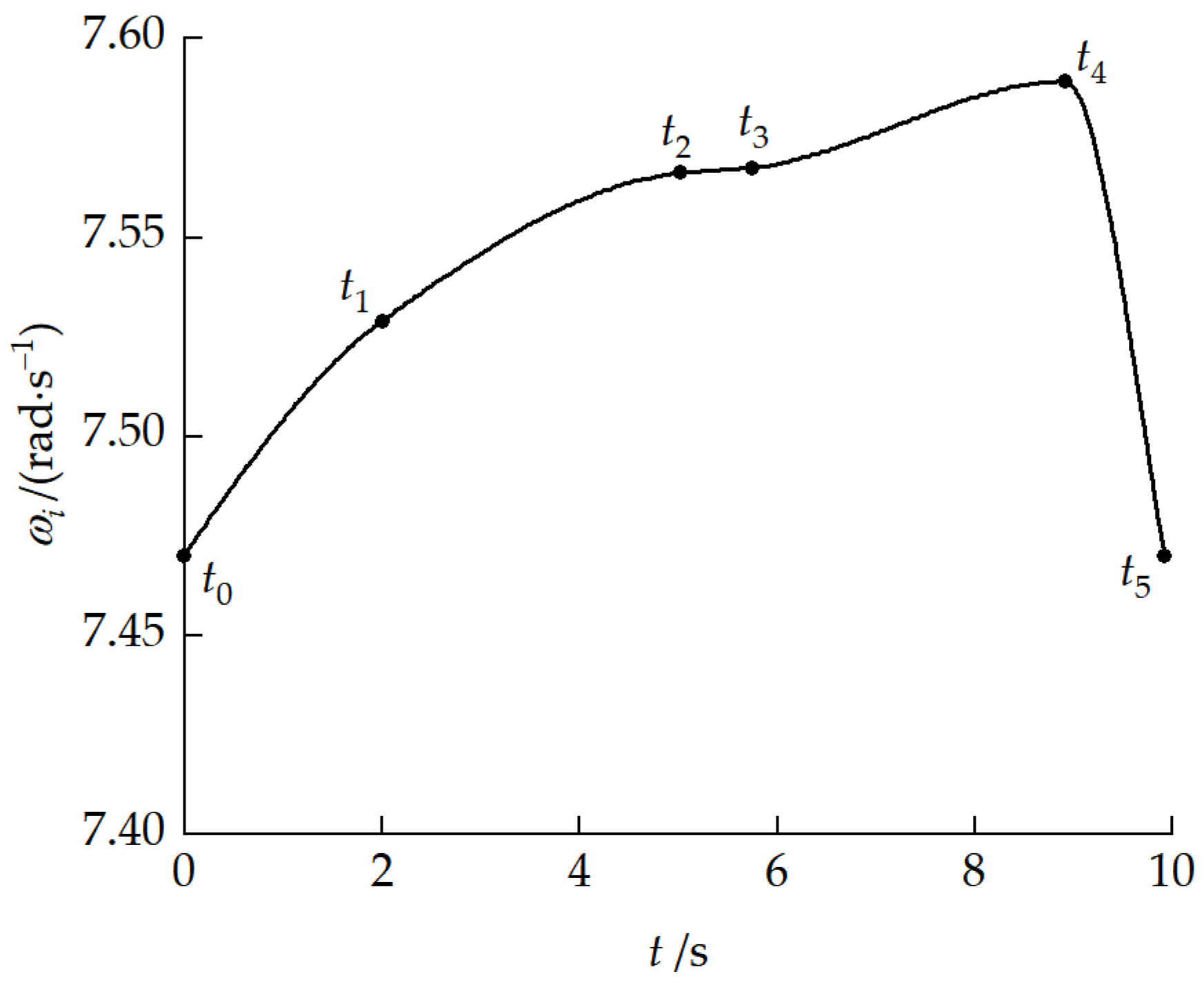

5.1. Constant-Velocity Driving Condition

5.2. Variable-Velocity Driving Condition

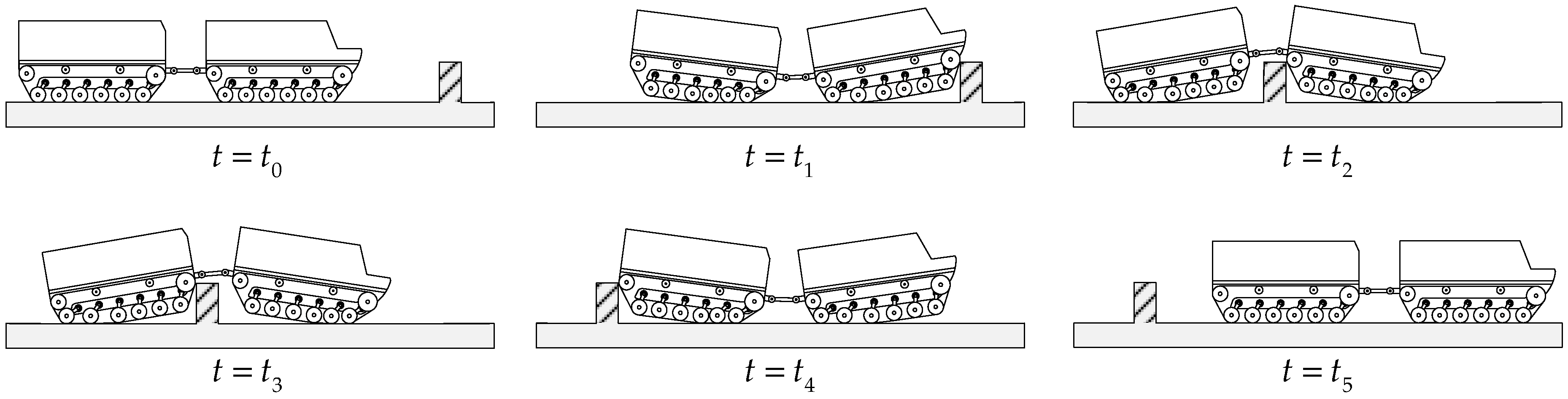

5.3. Cooperative Obstacle-Crossing Method

5.3.1. Motion Planning Framework

- (1)

- Obstacle-crossing action sequence generation

- (2)

- Trajectory time parameterization

- (3)

- Feasible trajectory constraint conditions

- •

- Cylinder stroke constraint: .

- •

- Cylinder extension/retraction velocity constraint: .

- •

- Maximum working pitch moment constraint: .

- •

- Drive sprocket angular acceleration constraint: .

- (4)

- Cooperative motion inverse solution

- (5)

- Command generation and execution

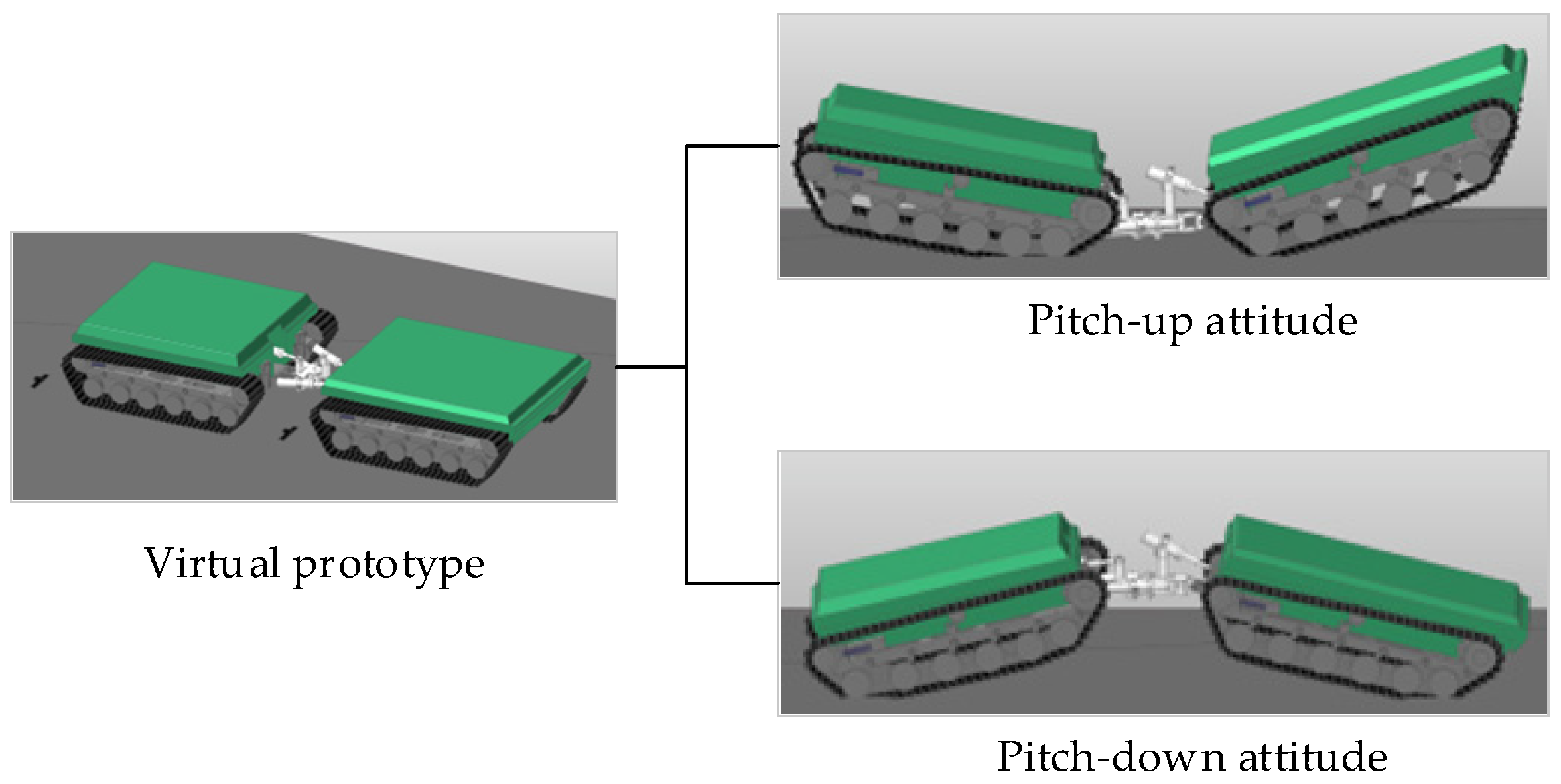

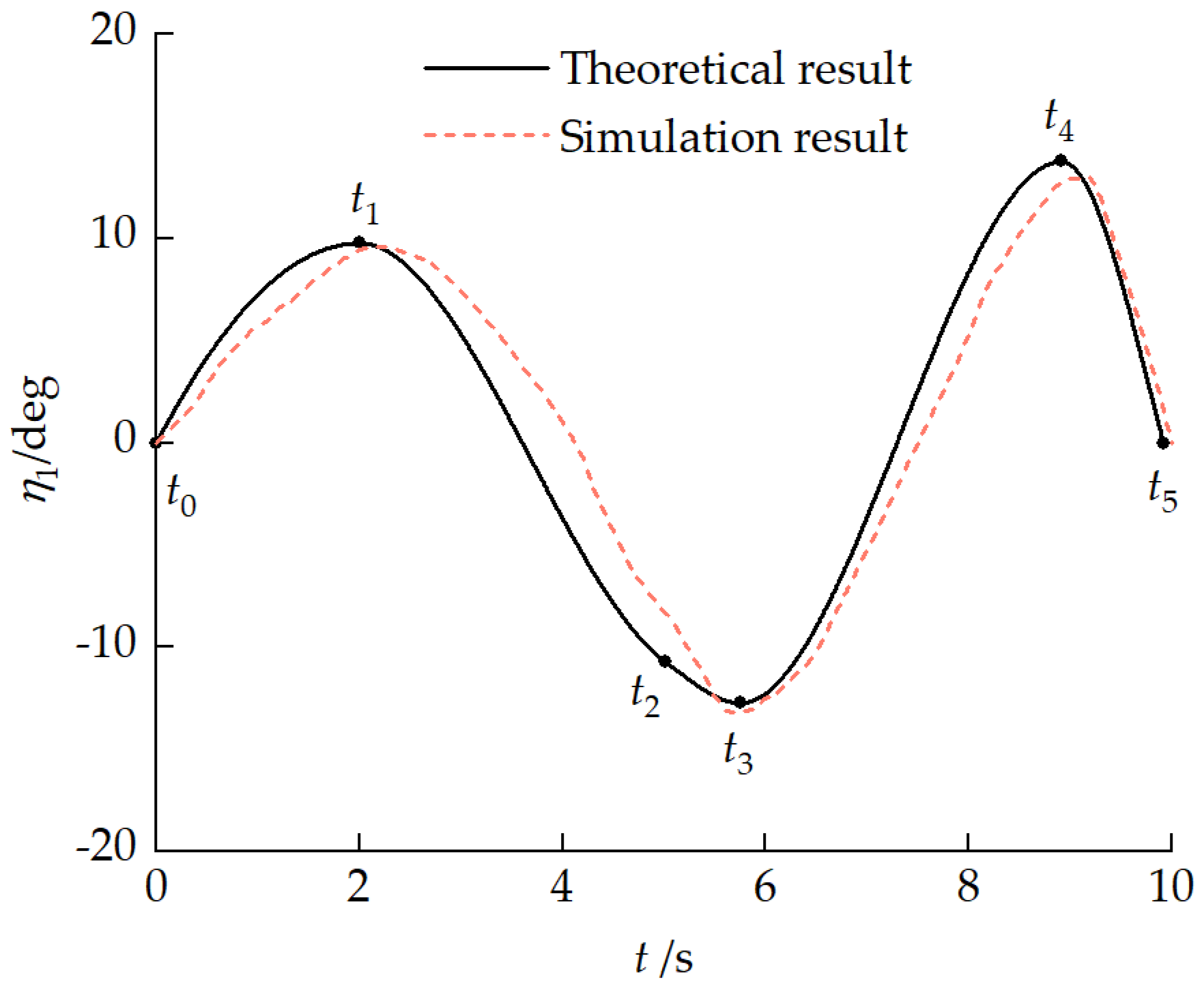

5.3.2. Obstacle-Crossing Case Validation

- •

- Phase 1: Approach phase (). The vehicle moved from its initial position until the front-unit track contacted the vertical-wall outer corner line. The vehicle transitioned from a horizontal state to a pitch-up attitude. The geometric constraint condition for this phase was that the front drive sprocket center was higher than the vertical wall .

- •

- Phase 2: Front-unit obstacle-crossing phase (). The front unit passed over the vertical-wall obstacle, from the front-unit track contacting the vertical-wall same-side outer corner line until the front-unit rear track left the vertical-wall opposite-side outer corner line. The vehicle transitioned from a pitch-up attitude to a pitch-down attitude. The geometric constraint condition for this phase was that the front idler wheel center was higher than the vertical wall .

- •

- Phase 3: Transition phase (). During this period, the pitch mechanism passed over the vertical wall, from the front-unit track leaving the vertical-wall opposite-side outer corner line until the rear-unit track contacted the same-side outer corner line. The vehicle maintained a pitch-down attitude. The geometric constraint condition for this phase was that the pitch mechanism’s lowest ground clearance point was higher than the vertical wall .

- •

- Phase 4: Rear-unit obstacle-crossing phase (). The rear unit passed over the vertical-wall obstacle, from the rear-unit track contacting the vertical-wall same-side diagonal line until the rear-unit track left the vertical-wall opposite-side outer corner line. The vehicle transitioned from a pitch-down attitude to a pitch-up attitude. The geometric constraint condition for this phase was that the rear idler wheel center was higher than the vertical wall .

- •

- Phase 5: Recovery phase (). The vehicle recovered from the pitch-up attitude to a horizontal state.

5.3.3. Comparison with Commercial Multibody Simulation

5.4. Energy-Saving Implications of Biomimetic Pitch Adjustment

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rieu, J.P.; Delanoë-Ayari, H.; Barentin, C.; Nakagaki, T.; Kuroda, S. Dynamics of centipede locomotion revealed by large-scale traction force microscopy. J. R. Soc. Interface 2024, 21, 20230439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, S.; Uchida, N.; Nakagaki, T. Gait switching with phase reversal of locomotory waves in the centipede Scolopocryptops rubiginosus. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2022, 17, 026005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, K.L.; Wood, R.J. Myriapod-like ambulation of a segmented microrobot. Auton. Robots 2011, 31, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoi, S.; Tanaka, T.; Fujiki, S.; Funato, T.; Senda, K.; Tsuchiya, K. Advantage of straight walk instability in turning maneuver of multilegged locomotion: A robotics approach. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui, K.; Sakai, K.; Kano, T.; Owaki, D.; Ishiguro, A. Decentralized control scheme for myriapod robot inspired by adaptive and resilient centipede locomotion. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Kitano, M. Study on Steerability of Articulated Tracked Vehicles—Part 1. Theoretical and Experimental Analysis. J. Terramech. 1986, 23, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, G. Research on Steering Path Tracking Performance of Articulated Quad-Tracked Vehicle Based on Fuzzy PID Control. J. Field Robot. 2025, 42, 3561–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Cheng, K. Trajectory Planning for an Articulated Tracked Vehicle and Tracking the Trajectory via an Adaptive Model Predictive Control. Electronics 2023, 12, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tota, A.; Velardocchia, M.; Rota, E. Steering Behavior of an Articulated Amphibious All-Terrain Tracked Vehicle; SAE Technical Paper 2020-01-0996; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tota, A.; Galvagno, E.; Velardocchia, M. Analytical Study on the Cornering Behavior of an Articulated Tracked Vehicle. Machines 2021, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, S.; Yamada, T.; Miyata, E. Articulated Tracked Vehicle with Four Degrees of Freedom. J. Terramech. 1991, 28, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Zhang, J.; Qu, Z.D. Research on Turning and Pitching Performance of Articulated Tracked Vehicle. Acta Armamentarii 2012, 33, 134–141. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dong, C.; Cheng, K.; Hu, K.L.; Hu, W.Q. Pitching Movement Performance of All Terrain Articulated Tracked Vehicles. J. Jilin Univ. (Eng. Technol. Ed.) 2017, 47, 827–836. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C. Research on Steering and Pitch Motion Performance of Articulated All-Terrain Tracked Vehicle. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2017. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, L.J.; Yang, Y.H. Analysis of Trench Crossing Performance of Articulated Tracked Vehicle on Unstructured Terrain. Mech. Des. 2012, 29, 17–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Hong, S.; Lee, C.H. Dynamic Analysis of an Articulated Tracked Vehicle on Undulating and Inclined Ground. In Proceedings of the ISOPE Ocean Mining Symposium, Maui, HI, USA, 19–24 June 2011; pp. 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhao, H.; Li, B.H. Simulation of Motion Characteristic of Miner with Articulated Vehicle on Seamount. Comput. Simul. 2008, 25, 195–199. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.T. Simulation Research on Articulated Tracked Vehicle for Cobalt-Rich Crust Mining. Master’s Thesis, Central South University, Changsha, China, 2007. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.G.; Liu, S.J.; Li, X.F. Simulation of Trench Crossing Performance of Articulated Tank Based on ADAMS/ATV. Ordnance Ind. Autom. 2009, 28, 35–38. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.G. Simulation Research on Trench Crossing Performance of Separable Articulated Tank. Master’s Thesis, Central South University, Changsha, China, 2009. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Research on Driving Performance of Articulated Tracked Vehicle. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2011. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Liu, X.; Chen, H. Modeling and Analysis of the Turning Performance of an Articulated Tracked Vehicle That Considers the Inter-Unit Coupling Forces. Machines 2025, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Sankar, S. Ride Dynamics of High-Speed Tracked Vehicles: Simulation with Field Validation. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 1994, 23, 379–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, J.; Watanabe, K. A Spatial Motion Analysis Model of Tracked Vehicles with Torsion Bar Type Suspension. J. Terramech. 2004, 41, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Zhang, Z. Dynamic Modeling of High-Mobility Tracked Vehicles and Analysis of the Optimization of Suspension Characteristics. Sci. Sin. Technol. 2023, 53, 1545–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimauro, L.; Venturini, S.; Tota, A. High-Speed Tracked Vehicle Model Order Reduction for Static and Dynamic Simulations. Def. Technol. 2024, 38, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Yu, H.L.; Dong, H.T.; Xi, J.Q. Refined Dynamics Modeling and Simulation of Special Tracked Vehicles. Acta Armamentarii 2024, 45, 1384–1401. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, X.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Bi, S. A Sky-Hook Positive Real Network Based ISD Seat Suspension for Commercial Vehicle. J. Vib. Control, 2026; online first. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, V.; Yang, X.; Liu, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, T.; Fu, D. A Novel Approach to Design and Control of Semi-Active Inertial Suspension System for Hub Motor Driven Vehicles. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2025, 13, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, M.G. Introduction to Terrain-Vehicle Systems. Part I: The Terrain. Part II: The Vehicle; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Reece, A.R. Principles of Soil-Vehicle Mechanics. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. 1965, 180, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janosi, Z.; Hanamoto, B. The Analytical Determination of Drawbar Pull as a Function of Slip for Tracked Vehicles in Deformable Soils. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on the Mechanics of Soil-Vehicle Systems, Torino, Italy, 12–16 June 1961; pp. 707–736. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.Y.; Preston-Thomas, J. On the Characterization of the Shear Stress-Displacement Relationship of Terrain. J. Terramech. 1983, 19, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.Y.; Chiang, C.F. A General Theory for Skid Steering of Tracked Vehicles on Firm Ground. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2001, 215, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.Y. Theory of Ground Vehicles, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wills, B.M.D. The Measurement of Soil Shear Strength and Deformation Moduli and a Comparison of the Actual and Theoretical Performance of a Family of Rigid Tracks. J. Terramech. 1964, 1, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.X. Modeling of Steady-State Performance of Skid-Steering for High-Speed Tracked Vehicles. J. Terramech. 2017, 73, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsich, D.; Vantsevich, V.; Paldan, J. Modelling and Simulation Fundamentals in Design for Ground Vehicle Mobility Part II: Western Approach. J. Terramech. 2025, 117, 101023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantsevich, V.; Gorsich, D. Modeling and Simulation Fundamentals in Design for Ground Vehicle Mobility Part I: Eastern Approach. J. Terramech. 2025, 117, 101020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wismer, R.D.; Luth, H.J. Off-Road Traction Prediction for Wheeled Vehicles. J. Terramech. 1973, 10, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosheck, J.E. Skid Steering of Crawlers. SAE Trans. 1975, 84, 1390–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclaurin, B. A Skid Steering Model with Track Pad Flexibility. J. Terramech. 2007, 44, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLaurin, B. A Skid Steering Model Using the Magic Formula. J. Terramech. 2011, 48, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvagno, E.; Rondinelli, E.; Velardocchia, M. Electro-Mechanical Transmission Modelling for Series-Hybrid Tracked Tanks. Int. J. Heavy Veh. Syst. 2012, 19, 256–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valouch, D.; Faigl, J. Caterpillar Heuristic for Gait-Free Planning with Multi-Legged Robot. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 5204–5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrani, A.; Rayhan, M.M.; Mackenson, T.; McDaniel, D.; Lagos, L. Smart Quadruped Robotics: A Systematic Review of Design, Control, Sensing and Perception. Adv. Robot. 2025, 39, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, I. Path Planning for Perpendicular Parking of Large Articulated Vehicles Based on Qualitative Kinematics and Geometric Methods. Vehicles 2023, 5, 876–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; He, Y. Design of a Tracking Controller for Autonomous Articulated Heavy Vehicles Using a Nonlinear Model Predictive Control Technique. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part K J. Multi-Body Dyn. 2024, 238, 334–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.Z.; Lu, H.N.; Yang, J.M. Multi-Body Dynamics Modeling and Straight-Line Travel Simulation of a Four-Tracked Deep-Sea Mining Vehicle on Flat Ground. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biological Structure | Engineering Structure | Functional Correspondence | Characteristic Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-segment dorsoventral joint | Hydraulic pitch mechanism | Active pitch adjustment | Pitch angle ±25–35° |

| Leg base compliant structure | Torsion bar spring suspension | Passive terrain adaptation | Passive adaptation |

| Multi-leg distributed contact | Multi-road-wheel track system | Load distribution and traction | Distributed ground contact |

| Anterior–posterior segment coordination | Front–rear unit coupled drive | Coordinated propulsion mode | Sequential activation |

| Symbol | Coordinates |

|---|---|

| Parameters | Value | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| /kg | 450 | /(kg·m2) | 0.0056 |

| /(kg·m2) | 65.7 | /(kg·m2) | 0.011 |

| /mm | 1080 | /mm | 765.5 |

| /mm | 230 | /mm | 849.5 |

| /deg | 56.07 | /mm | 370.73 |

| /mm | 100 | /mm | 678.75 |

| /deg | 25.13 | /deg | 17.31 |

| /mm | 209.5 | /mm | 333.88 |

| /mm | 1080 | /mm | 202.13 |

| /− | 6 | /deg | 2.75 |

| /(N·m/deg) | 123 | /deg | 4.54 |

| /deg | 33.52 | /− | 0.03 |

| /mm | 130.5 | /− | 0.025 |

| /mm | 67.5 | /− | 0.00015 |

| /mm | 75 | /− | 0.68 |

| /mm | 33 | /− | 0.12 |

| Parameters | Value | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| /mm | 205.82–305.82 | /mm | 261.7 |

| /mm | 207.51–307.51 | /mm | 125.1 |

| /deg | 73.42° | /mm | 295.86 |

| /deg | 60.13° | /MPa | 16 |

| /mm | 125 | /− | 0.9 |

| Parameter | Biological Prototype (Centipede) | ATV Simulation Results |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum pitch angle | 25–35° [2,3] | 26.87° |

| Traction distribution | Anterior-pull posterior-push [1] | Front-pull rear-push |

| Coordination mode | Wave-like segment Coordination [5] | Sequential phase coordination |

| /mm | /deg | /mm | /− | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | −5.02 | −5.00 | −4.96 | 1026.97 | 830.73 | 626.26 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 20 | −9.76 | −9.76 | −9.76 | 606.52 | 606.52 | 417.18 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 30 | −14.77 | −14.77 | −14.77 | 396.50 | 396.96 | 211.33 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Phase | Height | /deg | /deg | /mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.77 | −7.86 | −19 | |

| 2 | −10.76 | 9.83 | 22 | |

| 3 | −12.75 | 11.65 | 26 | |

| 4 | 13.77 | −10.41 | −26 |

| Moment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| / | 7.47 | 7.53 | 7.56 | 7.57 | 7.59 | 7.47 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, N.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. Theoretical Dynamics Modeling of Pitch Motion and Obstacle-Crossing Capability Analysis for Articulated Tracked Vehicles Based on Myriapod Locomotion Mechanism. Biomimetics 2026, 11, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020121

Li N, Liu X, Chen H, Zhang Y, Zhang S. Theoretical Dynamics Modeling of Pitch Motion and Obstacle-Crossing Capability Analysis for Articulated Tracked Vehicles Based on Myriapod Locomotion Mechanism. Biomimetics. 2026; 11(2):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020121

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ningyi, Xixia Liu, Hongqian Chen, Yu Zhang, and Shaoliang Zhang. 2026. "Theoretical Dynamics Modeling of Pitch Motion and Obstacle-Crossing Capability Analysis for Articulated Tracked Vehicles Based on Myriapod Locomotion Mechanism" Biomimetics 11, no. 2: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020121

APA StyleLi, N., Liu, X., Chen, H., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, S. (2026). Theoretical Dynamics Modeling of Pitch Motion and Obstacle-Crossing Capability Analysis for Articulated Tracked Vehicles Based on Myriapod Locomotion Mechanism. Biomimetics, 11(2), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020121