Bio-Inspired Reactive Approaches for Automated Guided Vehicle Path Planning: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Swarm Intelligence Algorithms

2.1. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

2.2. Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm (ACO)

2.3. Genetic Algorithm (GA)

3. Artificial Intelligence Algorithms

3.1. Neural Network (NN)

3.2. Reinforcement Learning (RL)

3.3. Fuzzy Logic (FL)

4. Others

5. Discussion and Conclusions

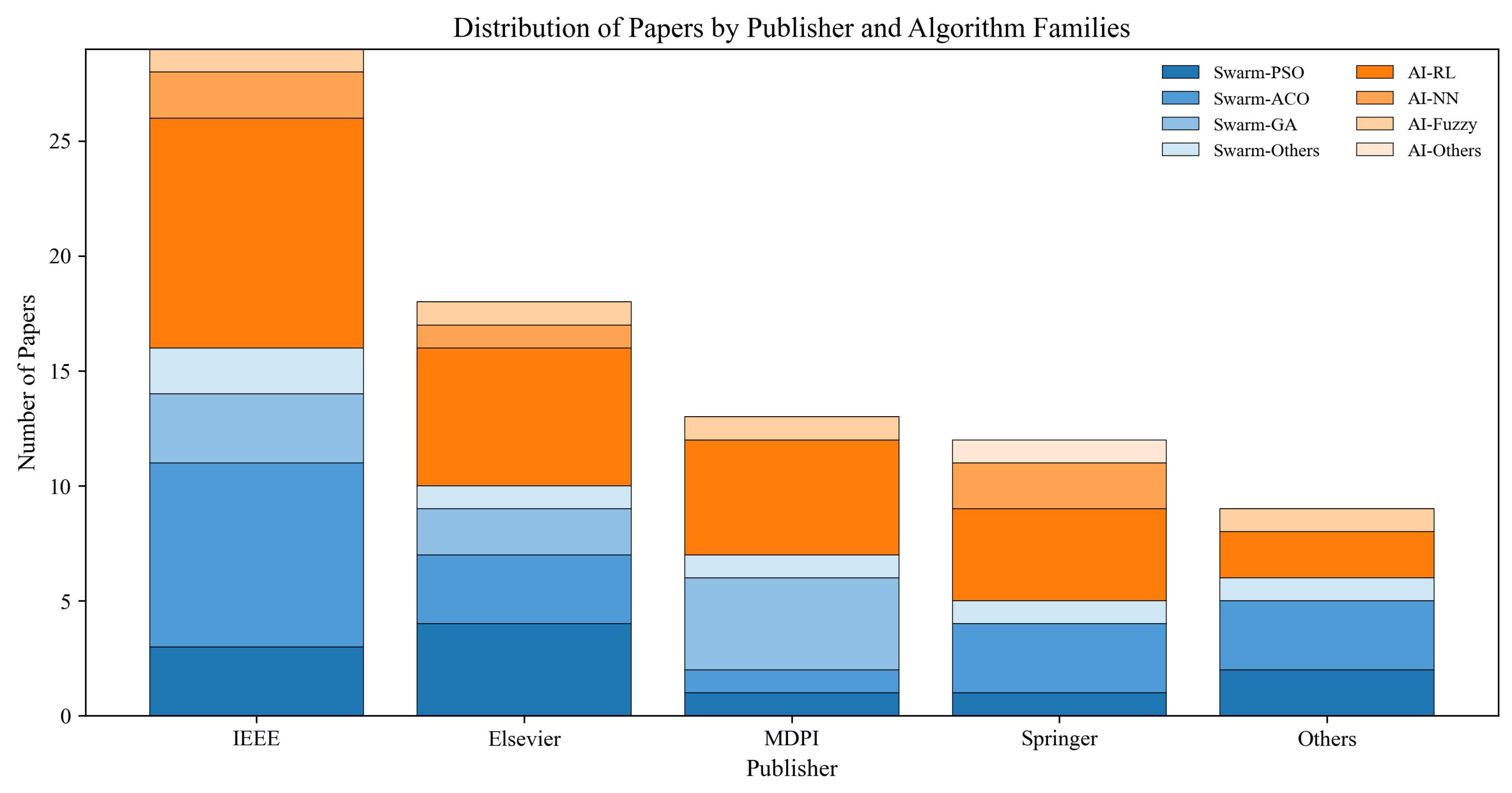

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusions

- How to reduce the gap between the simulation environment and the real-world AGV operation environment, or how to enhance the realism of the simulation environment when validating the algorithms?

- How to address environmental uncertainty and unpredictable obstacles when maintaining the online implementation of the algorithms with the safety and completeness constraints of path planning?

- How to improve the sim-to-real transfer or generalization ability of the AGV path planning algorithm through embodied intelligence, transfer learning, or other approaches?

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGV | Automated guided vehicle |

| RRT | Rapidly-exploring random tree |

| APF | Artificial potential field |

| PRM | Probabilistic roadmap |

| PSO | Particle swarm optimization |

| SA | Simulated annealing |

| GWO | Grey wolf optimizer |

| MOPSO | Multi-objective particle swarm optimization |

| DWA | Dynamic window approach |

| FOA | Fruit fly optimization algorithm |

| EDA | Estimation of distribution algorithm |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory |

| DQN | Deep-Q network |

| D3QN | Dueling double deep-Q network |

| DRL | Deep reinforcement learning |

| RNN | Recurrent neural network |

| PPO | Proximal policy optimization |

| ICM | Intrinsic curiosity module |

| DDPG | Deep deterministic policy gradient |

| MPC | Model predictive controller |

| DE | Differential evolution |

| FL | Fuzzy logic |

References

- De Ryck, M.; Versteyhe, M.; Debrouwere, F. Automated guided vehicle systems, state-of-the-art control algorithms and techniques. J. Manuf. Syst. 2020, 54, 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhang, W.; Peng, T.; Zheng, J. Energy-efficient path planning for a single-load automated guided vehicle in a manufacturing workshop. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 158, 107397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshayedi, A.J.; Jinsong, L.; Liao, L. AGV (automated guided vehicle) robot: Mission and obstacles in design and performance. J. Simul. Anal. Nov. Technol. Mech. Eng. 2019, 12, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Madridano, A.; Al-Kaff, A.; Martín, D.; de la Escalera, A. Trajectory planning for multi-robot systems: Methods and applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 173, 114660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Liu, A.; Wang, J.; Kong, X. An intelligence-based hybrid PSO-SA for mobile robot path planning in warehouse. J. Comput. Sci. 2023, 67, 101938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Liu, A.; Wang, J.; Kong, X. A Review of Path-Planning Approaches for Multiple Mobile Robots. Machines 2022, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julius Fusic, S.; Kanagaraj, G.; Hariharan, K.; Karthikeyan, S. Optimal path planning of autonomous navigation in outdoor environment via heuristic technique. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 12, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jin, H.; Seo, M.; Har, D. Optimal Path Planning of Automated Guided Vehicle using Dijkstra Algorithm under Dynamic Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2019 7th International Conference on Robot Intelligence Technology and Applications (RiTA), Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 1–3 November 2019; pp. 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Fang, M.; Su, Y. AGV path planning based on improved Dijkstra algorithm. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 1746, 012052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmasiri, P.; Kavalchuk, I.; Akbari, M. Novel implementation of multiple automated ground vehicles traffic real time control algorithm for warehouse operations: Djikstra approach. Oper. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2020, 13, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Yang, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhou, Y.; Postolache, O.; Ge, Y.E. Priority-based speed control strategy for automated guided vehicle path planning in automated container terminals. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2020, 42, 3079–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Zhu, J.; Shen, L. An Improved Acceleration Method Based on Multi-Agent System for AGVs Conflict-Free Path Planning in Automated Terminals. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 3326–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Research on AGV Real-Time Path Planning and Obstacle Detection Based on Machine Vision. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 5th International Conference on Electronic Technology, Communication and Information (ICETCI), Changchun, China, 23–25 May 2025; pp. 1454–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, H.; Li, J.; Jiang, L.; Li, J.; Jiang, F. AGV path planning algorithm based on improved Dijkstra algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Internet of Things, Automation and Artificial Intelligence (IoTAAI), Guangzhou, China, 26–28 July 2024; pp. 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransen, K.; van Eekelen, J. Efficient path planning for automated guided vehicles using A*(Astar) algorithm incorporating turning costs in search heuristic. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, C.; Zhang, G. AGV path planning based on improved A-star algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC), Chongqing, China, 15–17 March 2024; Volume 7, pp. 1590–1595. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xie, W.; Zhang, L. Cyber-Physical System-Based Heuristic Planning and Scheduling Method for Multiple Automatic Guided Vehicles in Logistics Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 7882–7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Chi, X.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, W.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, D. Dynamic Path Planning for Forklift AGV Based on Smoothing A* and Improved DWA Hybrid Algorithm. Sensors 2022, 22, 7079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Pan, X.; Liu, Z. AGV Path Planning Algorithm Based on Fusion of Improved A* and DWA. In Proceedings of the 2024 43rd Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Kunming, China, 28–31 July 2024; pp. 1782–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Xie, W.; Zhang, L. A Probabilistic Time-Constrained Based Heuristic Path Planning Algorithm in Warehouse Multi-AGV Systems. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 2538–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Li, R.; Zhao, L.; Wang, K.; Gui, X. Multi-obstacle path planning and optimization for mobile robot. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 183, 115445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, B.; Ben-Tzvi, P. Physics based path planning for autonomous tracked vehicle in challenging terrain. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2019, 95, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Yu, H. Research on the Safety of AGV Path Planning Based on D* Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Applications (ICAICA), Dalian, China, 28–30 November 2024; pp. 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, J.; Cai, X.; Chen, Y.; Peng, E.; Zou, X. AGV Path Planning for Logistics Warehouse by Using an Improved D*Lite Algorithm. In Proceedings of the TEPEN 2022; Zhang, H., Ji, Y., Liu, T., Sun, X., Ball, A.D., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1018–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Li, G.; Hou, J.; Chen, L.; Hu, N. A Path Planning Method for Underground Intelligent Vehicles Based on an Improved RRT* Algorithm. Electronics 2022, 11, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, W.; Gao, Y.; Wang, D.; Fan, Z. PQ-RRT*: An improved path planning algorithm for mobile robots. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 152, 113425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, W.; Ding, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, G.; Sun, L. A Generalized Voronoi Diagram-Based Efficient Heuristic Path Planning Method for RRTs in Mobile Robots. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 4926–4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Yang, Z.; Lv, L.; Shi, Y. A Bi-Level Path Planning Algorithm for Multi-AGV Routing Problem. Electronics 2020, 9, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhang, W.; Chi, X.; Jiang, D.; Yi, Y.; Lu, Y. A Novel AGV Path Planning Approach for Narrow Channels Based on the Bi-RRT Algorithm with a Failure Rate Threshold. Sensors 2023, 23, 7547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Luo, Y.; Tan, X. Path Planning for Automatic Guided Vehicles (AGVs) Fusing MH-RRT with Improved TEB. Actuators 2021, 10, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lu, Y.; Lv, L. GVP-RRT: A grid based variable probability Rapidly-exploring Random Tree algorithm for AGV path planning. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 8273–8286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chai, R.; Chai, S.; Xia, Y.; Tsourdos, A. Design and Practical Implementation of a High Efficiency Two-Layer Trajectory Planning Method for AGV. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 1811–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Hu, Z.; Wei, M.; Guo, P.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, A. Improved A* algorithm incorporating RRT* thought: A path planning algorithm for AGV in digitalised workshops. Comput. Oper. Res. 2025, 177, 106993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanski, R.; Tarczewski, T.; Erwinski, K. Energy Efficient Local Path Planning Algorithm Based on Predictive Artificial Potential Field. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 39729–39742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Ni, L.; Zhao, C.; Lei, C.; Du, Y.; Wang, W. TriPField: A 3D potential field model and its applications to local path planning of autonomous vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 3541–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanski, R.; Bereit, A.; Tarczewski, T. Efficient Local Path Planning Algorithm Using Artificial Potential Field Supported by Augmented Reality. Energies 2021, 14, 6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, C.; Wu, H.; Postolache, O.; Wu, Y. An improved artificial potential field method for multi-AGV path planning in ports. Intell. Robot. 2025, 5, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, B. AGV Path Planning Based on Improved Artificial Potential Field Method. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Computer Applications (ICPECA), Shenyang, China, 22–24 January 2021; pp. 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. Research on AGV Path Planning Algorithm Integrating Adaptive A* and Improved APF Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2025 8th International Conference on Advanced Algorithms and Control Engineering (ICAACE), Shanghai, China, 21–23 March 2025; pp. 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lu, Y.; Lv, L. Grid-Based Non-Uniform Probabilistic Roadmap-Based AGV Path Planning in Narrow Passages and Complex Environments. Electronics 2024, 13, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žužek, T.; Vrabič, R.; Zdešar, A.; Škulj, G.; Banfi, I.; Bošnak, M.; Zaletelj, V.; Klančar, G. Simulation-Based Approach for Automatic Roadmap Design in Multi-AGV Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 6190–6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenzel, J.; Schmitz, L. Automated Roadmap Graph Creation and MAPF Benchmarking for Large AGV Fleets. In Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Conference on Automation, Robotics and Applications (ICARA), Prague, Czech Republic, 18–20 February 2022; pp. 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jathunga, T.; Rajapaksha, S. Improved Path Planning for Multi-Robot Systems Using a Hybrid Probabilistic Roadmap and Genetic Algorithm Approach. J. Robot. Control (JRC) 2025, 6, 715–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chai, R.; Chen, K.; Zhang, J.; Chai, S.; Xia, Y.; Tsourdos, A. Efficient and Near-Optimal Global Path Planning for AGVs: A DNN-Based Double Closed-Loop Approach with Guarantee Mechanism. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, M.; Onsy, A.; Haikal, A.Y.; Ghanbari, A. Path planning algorithms in the autonomous driving system: A comprehensive review. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 174, 104630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.; Sang, H.; Guo, H.; Wang, P. Improved particle swarm optimization algorithm for AGV path planning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 33522–33531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Liu, A.; Wang, J.; Kong, X. An improved fault-tolerant cultural-PSO with probability for multi-AGV path planning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, F.; Rahiman, W.; Alhady, S.S.N.; Ali, A.; Mir, I.; Jalil, A. Meta-heuristic approach for solving multi-objective path planning for autonomous guided robot using PSO–GWO optimization algorithm with evolutionary programming. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 12, 7873–7890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.K.; Ngo, T.G.; Pan, J.S.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Nguyen, T.T. Enhancing Path Planning Capabilities of Automated Guided Vehicles in Dynamic Environments: Multi-Objective PSO and Dynamic-Window Approach. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Wahab, M.N.A.; Ramli, A.; Misro, M.Y.; Ezza, W.Z.; Hasan, W.Z.W. Enhancing performance of global path planning for mobile robot through Alpha–Beta Guided Particle Swarm Optimization (ABGPSO) algorithm. Measurement 2025, 257, 118633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Tang, S. Improved Human Optimisation Algorithm for Global Path Planning in AGV. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Application (ICCEA), Hangzhou, China, 12–14 April 2024; pp. 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. Automatic Guided Vehicle Global Path Planning Considering Multi-objective Optimization and Speed Control. Sensors Mater. 2021, 33, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, N.; Ling, X. Study on Conflict-free AGVs Path Planning Strategy for Workshop Material Distribution Systems. Procedia CIRP 2021, 104, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, D. Research on AGV path planning based on PSO-IACO algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Mechatronics Technology (ICEEMT), Qingdao, China, 2–4 July 2021; pp. 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, G.; Feng, Z.; Mei, T.; Li, P.; Jin, W.; Chen, S. Multi-AGVs path planning based on improved ant colony algorithm. J. Supercomput. 2019, 75, 5898–5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, H.; Zhang, C. Path planning for intelligent parking system based on improved ant colony optimization. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 65267–65273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Chen, H. Unmanned vehicle path planning using a novel ant colony algorithm. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2019, 2019, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huang, X.; Cui, J.; Liu, C.; Xiao, W. Modified adaptive ant colony optimization algorithm and its application for solving path planning of mobile robot. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 215, 119410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, F.; Luo, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Sun, Z. Research on AGV Path Planning Based on Gray wolf Improved Ant Colony Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2022 5th International Conference on Robotics, Control and Automation Engineering (RCAE), Changchun, China, 28–30 October 2022; pp. 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, N. Airport AGV path optimization model based on ant colony algorithm to optimize Dijkstra algorithm in urban systems. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2022, 35, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Gong, D.; Wang, M.; Dai, X. Path planning of mobile robot with improved ant colony algorithm and MDP to produce smooth trajectory in grid-based environment. Front. Neurorobot. 2020, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Tang, C.; Cai, W. Research on Dynamic Path Planning Based on the Fusion Algorithm of Improved Ant Colony Optimization and Rolling Window Method. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 28322–28332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, J.; Bai, Z.; Wei, Z.; Peng, J. Toward Optimization of AGV Path Planning: An RRT*-ACO Algorithm. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 18387–18399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, Z.; Tan, Y.; Liu, H.; Song, C. Research on Multi-AGVs Path Planning and Coordination Mechanism. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 213345–213356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Guo, J. A novel hexagonal grid map model and regenerated heuristic factor based strategy for intelligent manufacturing system’s AGV path planning problem solving. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 192, 110154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, K. Research on AGV Path Planning Design Based on Reinforcement Learning-Ant Colony Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 4th International Conference on Electronic Technology, Communication and Information (ICETCI), Changchun, China, 24–26 May 2024; pp. 1148–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, B.; Yang, Y.; Wu, H. Quantum ant colony optimization algorithm for AGVs path planning based on Bloch coordinates of pheromones. Nat. Comput. 2020, 19, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yu, Y.; Xin, L. Research on Path Planning of AGV Based on Improved Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2021 33rd Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Kunming, China, 22–24 May 2021; pp. 7567–7572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Yu, X.; Sun, K.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, G. Multiobjective path optimization of an indoor AGV based on an improved ACO-DWA. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2022, 19, 12532–12557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, X. Research on Optimization Algorithm of AGV Scheduling for Intelligent Manufacturing Company: Taking the Machining Shop as an Example. Processes 2023, 11, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, H.; Xie, R. Improved Ant Colony Algorithm Based on Parameters Optimization for AGV Path Planning. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Symposium on Computer Engineering and Intelligent Communications (ISCEIC), Nanjing, China, 6–8 August 2021; pp. 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Song, Q.; Li, M. Multi-AGV multitask collaborative scheduling based on an improved ant colony algorithm. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2025, 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Song, Y.; He, C.; Lei, Q.; Guo, W. Approach to integrated scheduling problems considering optimal number of automated guided vehicles and conflict-free routing in flexible manufacturing systems. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 74909–74924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Yang, Y.; Dessouky, Y.; Postolache, O. Multi-AGV scheduling for conflict-free path planning in automated container terminals. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 142, 106371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, L. A Three Stage Optimal Scheduling Algorithm for AGV Route Planning Considering Collision Avoidance under Speed Control Strategy. Mathematics 2023, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goli, A.; Tirkolaee, E.B.; Aydın, N.S. Fuzzy integrated cell formation and production scheduling considering automated guided vehicles and human factors. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 29, 3686–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, S.; Hu, X. Cooperative Path Planning of UAVs & UGVs for a Persistent Surveillance Task in Urban Environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 4906–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.; Fu, Y.; Dong, X. Omnidirectional AGV Path Planning Based on Improved Genetic Algorithm. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, M.; Ren, F. A Method of Dual-AGV-Ganged Path Planning Based on the Genetic Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P. Grid-Map-Based Path Planning and Task Assignment for Multi-Type AGVs in a Distribution Warehouse. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, B.; Bao, J.; Raza, H.; Sun, Y.; Ma, Q. Flow-shop path planning for multi-automated guided vehicles in intelligent textile spinning cyber-physical production systems dynamic environment. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 59, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, I.; Choi, B.; Nielsen, P. On the training of a neural network for online path planning with offline path planning algorithms. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 102142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, R.; Liu, D.; Liu, T.; Tsourdos, A.; Xia, Y.; Chai, S. Deep learning-based trajectory planning and control for autonomous ground vehicle parking maneuver. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 20, 1633–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liang, X.; Song, W.; Chen, Y. Multi-dimensional AGV Path Planning in 3D Warehouses Using Ant Colony Optimization and Advanced Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advanced Intelligent Computing Technology and Applications; Huang, D.S., Zhang, Q., Zhang, C., Chen, W., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 180–191. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M.; Lu, L.; Ni, H.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J. Research on dynamic path planning method of moving single target based on visual AGV. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Yao, X.; Jiang, Z.; Meng, J. AGV Path Planning with Dynamic Obstacles Based on Deep Q-Network and Distributed Training. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2025, 12, 1005–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Peng, L. Multi-robot path planning based on a deep reinforcement learning DQN algorithm. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2020, 5, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Pan, T.; Wang, K.; Cui, S. Research on AGV Path Planning Based on Improved DQN Algorithm. Sensors 2025, 25, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Ren, Z.; Wu, Z.; Lai, J.; Zeng, D.; Xie, S. A Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Approach for AGVs Path Planning. In Proceedings of the 2020 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Shanghai, China, 6–8 November 2020; pp. 6833–6838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, C.; Yan, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, Y. Automated guided vehicle dispatching and routing integration via digital twin with deep reinforcement learning. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 72, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Hue, G.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Zhu, J. A Multi-AGV Routing Planning Method Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning and Recurrent Neural Network. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2024, 11, 1720–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Zhang, G.; Lu, X.; Wang, H.; Sheng, C.; Sun, L. Reinforcement learning method based on sample regularization and adaptive learning rate for AGV path planning. Neurocomputing 2025, 614, 128820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Lin, Y.; Yan, J.; Meng, Q.; Festl, K.; Schichler, L.; Watzenig, D. AGV Path Planning Using Curiosity-Driven Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 19th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Auckland, New Zealand, 26–30 August 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Yu, Z.; Huang, J.; Ao, T.; Li, W.; Zhou, Y. Graph-reinforcement-learning-based distributed path planning for collaborative multi-AGV systems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 328, 114255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, W.; Zheng, Q.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Wang, S. Path Planning of Mobile Robot in Dynamic Obstacle Avoidance Environment Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 189136–189152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wang, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Xu, P.; He, Z.; Du, H. Path Planning for Multi-AGV Systems Based on Globally Guided Reinforcement Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS), Nanjing, China, 18–20 October 2024; pp. 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Wang, D. A Global Path Planning Algorithm for Robots Using Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Dali, China, 6–8 December 2019; pp. 1693–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Ding, X.; Hu, D.; Jiang, Y. Research on Dynamic Path Planning of Multi-AGVs Based on Reinforcement Learning. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Tan, M.K.; Lim, K.G.; Chuo, H.S.E.; Yang, B.; Teo, K.T.K. Improved Q-Learning Algorithm for Path Planning of an Automated Guided Vehicle (AGV). In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Engineering and Technology (IICAIET), Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 12–14 September 2023; pp. 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, C.H.; Chang, D. A Machine Learning-Based Approach for Multi-AGV Dispatching at Automated Container Terminals. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kang, Y.S.; Do Noh, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, H. Digital Twin-Driven Reinforcement Learning for Dynamic Path Planning of AGV Systems. In Proceedings of the Advances in Production Management Systems. Production Management Systems for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous Environments; Thürer, M., Riedel, R., von Cieminski, G., Romero, D., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 351–365. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Jia, X.; Liu, K.; Sun, B. Self-Adaptive Traffic Control Model with Behavior Trees and Reinforcement Learning for AGV in Industry 4.0. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 7968–7979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, C. Improved Q-Learning Algorithm for AGV Path Optimization. In Proceedings of the Advanced Manufacturing and Automation XIII; Wang, Y., Yu, T., Wang, K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y. Path planning and decision algorithm design of intelligent AGV in electric vehicle overhead channel shared charging system. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 4th International Conference on Electronic Technology, Communication and Information (ICETCI), Changchun, China, 24–26 May 2024; pp. 986–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Yang, S. Research on multi-AGV path planning based on map training and action replanning. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2025, 18, 821–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Han, M.; Ren, N.; Hou, Y. AGV path planning method and intelligent obstacle avoidance strategy for intelligent manufacturing workshops. J. Comput. 2024, 35, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, S.; Zhao, J.; Wu, H.; Xian, J.; Montewka, J. Autonomous port management based AGV path planning and optimization via an ensemble reinforcement learning framework. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 251, 107087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Deng, Z.; Shi, Y.; Shen, W. Toward Energy-Efficient Routing of Multiple AGVs with Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Ren, Z.; Lai, J.; Wu, Z.; Xie, S. Optimal navigation for AGVs: A soft actor–critic-based reinforcement learning approach with composite auxiliary rewards. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 124, 106613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, A.; Dong, S. IACO-DQ Path Planning for AGV in Complex and Dynamic Environments. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Robotics and Computer Vision (ICRCV), Wuxi, China, 20–22 September 2024; pp. 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Ji, S.; Yao, Y.; Chen, C. A decentralized path planning model based on deep reinforcement learning. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 117, 109276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, S.; Zhao, Y.; Song, C.; Li, F. Improved Dyna-Q: A Reinforcement Learning Method Focused via Heuristic Graph for AGV Path Planning in Dynamic Environments. Drones 2022, 6, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Chen, X. Dynamic Path Planning for Unmanned Vehicles Based on Fuzzy Logic and Improved Ant Colony Optimization. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 62107–62115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, S.; Xu, B. Path Planning and Trajectory Tracking for Autonomous Obstacle Avoidance in Automated Guided Vehicles at Automated Terminals. Axioms 2024, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Geng, C.; Qi, B.; Meng, A.; Xiao, J. Research and experiment on global path planning for indoor AGV via improved ACO and fuzzy DWA. Electron. Res. Arch. 2023, 31, 19152–19173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambuj; Machavaram, R. Intelligent path planning for autonomous ground vehicles in dynamic environments utilizing adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy control. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 144, 110119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liang, W.; Shi, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q. Optimal time reuse strategy-based dynamic multi-AGV path planning method. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 7089–7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Sang, H.Y.; Zhang, B.; Duan, P.; Zou, W.Q. BDE-Jaya: A binary discrete enhanced Jaya algorithm for multiple automated guided vehicle scheduling problem in matrix manufacturing workshop. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2024, 89, 101651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, W.; Yang, C.; Wang, W.; Qie, T.; Xiang, C. An Optimization-Based Path Planning Approach for Autonomous Vehicles Using the DynEFWA-Artificial Potential Field. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2022, 7, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; He, R.; Yang, K. A bioinspired path planning approach for mobile robots based on improved sparrow search algorithm. Adv. Manuf. 2022, 10, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xia, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Xu, K. Hybrid Optimization Path Planning Method for AGV Based on KGWO. Sensors 2024, 24, 5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, N.; He, X.J. Integrated Optimization of Process Planning and Scheduling Considering Agv Path Planning. SSRN 2025, 5281476. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Peng, X. Trajectory Planning and Tracking Strategy Applied to an Unmanned Ground Vehicle in the Presence of Obstacles. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 18, 1575–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Paper | Algorithm | Consideration | Model | Online | Properties | Scenario | Hybrid | Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [2] | MOPSO | Multi-objective optimization: energy consumption, total execution time | Graph | No | Dynamic conditions | Single robot, manufacturing workshop | No | Simulation |

| [49] | MOPSO, DWA | Energy consumption, collisions, travel time, smoothness | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [46] | PSO | Shortest transportation time | - | No | Static | Single robot, one-line production line | No | Simulation |

| [5] | PSO, SA | Path length and smoothness, collision avoidance | Binary map | Yes | Static | Single robot, warehouse | Yes | Simulation, Experiment |

| [48] | PSO, GWO | Path length and smoothness | 2D map | No | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [50] | PSO | Safety, time, and distance | 2D map | No | Static | Single robot | No | Simulation |

| [52] | PSO | Smoothness, path length | 2D map | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [53] | PSO, ACO | Conflict avoidance, total driving time | Node | No | Static | Multi-robots, Workshop Material Distribution System | Yes | Simulation |

| [47] | PSO, GA | Length, collision | Grid space | Yes | Dynamic | Multi-robots | Yes | Simulation |

| [54] | PSO, ACO | Length, collision | Grid space | No | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [51] | PSO, Human optimization algorithm | Convergence, length | Raster map | No | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| Paper | Algorithm | Consideration | Model | Online | Properties | Scenario | Hybrid | Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [55] | ACO | Total completion time, transportation time, time for processing the job | Grid space | No | Static | Multi-robots, production workshop | No | Simulation |

| [56] | ACO | Path length | Topological map | No | Static | Single robot, AGV-based intelligent parking system | No | Simulation |

| [57] | ACO | Path length | Grid space | No | Dynamic | Single robot | No | Simulation |

| [58] | ACO | Path length, turn times | Grid space | No | Static | Single robot | No | Simulation |

| [60] | ACO, Dijkstra | Path length | Grid space | No | Static | Single robot, airport | Yes | Simulation |

| [61] | ACO, A* Multi-Directional | Distance, turning times and angle | Grid space | No | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [62] | ACO, rolling window | Path length, energy consumption | Grid space | Yes | Static | Single robot, complex dynamic environment | Yes | Simulation |

| [63] | ACO, RRT* | Path length, iterations, runtime | Grid space | No | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [64] | ACO | Distance | Grid space | No | Static | Multi-robots | No | Simulation |

| [65] | ACO | Path length | Grid | No | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [66] | ACO | Iterations, obstacle avoidance, path smoothness | Grid | No | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [67] | ACO | Distance, obstacle | Grid | No | Static | Single robot, automated container terminal | Yes | Simulation |

| [68] | ACO | Path length, turning angles | Matrix yard storage mode, grid | No | Static | Single robot, automatic container terminal | Yes | Simulation |

| [59] | ACO, GWO | Path smoothness, convergence | Grid | No | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [69] | ACO, DWA | Turns, path length | Grid | No | Static | Single robot, indoor environment | Yes | Simulation, Experiment |

| [70] | ACO | Material flow and path length | Raster map | No | Static | Single robot, job shop | No | Simulation |

| [71] | ACO, GA | Distance, iterations | Grid map | No | Static | Single robot | No | Simulation |

| [72] | ACO | Distance factors, task execution time, waiting time | Grid map | No | Static | Multi-robots, factory environment | No | Simulation |

| Paper | Algorithm | Consideration | Model | Online | Properties | Scenario | Hybrid | Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [73] | GA, Dijkstra, time window | Minimize the make span, the number of AGVs | Grid space | No | Static | Multi-robots, flexible manufacturing system | Yes | Simulation |

| [74] | GA, PSO, fuzzy logic controller | Delayed completion time, deadlocks | Grid space | No | Static | Multi-robots, automated container terminals | Yes | Simulation |

| [76] | GA, heuristic | Intercellular transportation and makespan-related costs | Grid space | No | Static | Multi-robots, cellular manufacturing system | Yes | Simulation |

| [77] | GA, EDA | Flight heights, blocking of buildings | Grid space | Yes | Dynamic | Multi-robots, cooperative, surveillance, urban environment | Yes | Simulation |

| [78] | GA, SA | Path smoothness | Grid | No | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation, Experiment |

| [79] | GA | Smooth and safe movement | Grid | No | Static | Multi-robots, Cooperative | No | Simulation, Experiment |

| [80] | GA, A* | Task completion time, energy consumption | Raster map, Grid | Yes | Static | Multi-robots | Yes | Simulation |

| [75] | GA | Completion time | Road network model | No | Static | Multi-robots | Yes | Simulation |

| [81] | GA | Path length | 2D map | Yes | Dynamic | Multi-robots | No | Simulation |

| Paper | Algorithm | Consideration | Model | Online | Properties | Scenario | Hybrid | Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [82] | Neural network, the Bellman–Ford algorithm, a quadratic program | The sum of the distance | Grid-based graph | Yes | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [83] | RDNN, LSTM | Collision, time, process and terminal costs | - | Yes | Static | Single robot, parking | Yes | Simulation, Experiment |

| [84] | Neural network, ACO | Path length | Grid | Yes | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [85] | NAR neural network, A* | Velocity, motion path | 2D map | Yes | Dynamic | Moving single target | Yes | Simulation |

| [44] | Deep neural network (DNN) | Path length, target, obstacles | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| Paper | Algorithm | Consideration | Model | Online | Properties | Scenario | Hybrid | Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [91] | DRL, RNN, PPO, LSTM | Position, obstacles, distance, spacing | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Multiple robots, automated storage and retrieval system (AS/RS) | Yes | Simulation |

| [97] | Q-Learning | Path length and smoothness | Graph | Yes | Static | Single robot | No | Simulation, Experiment |

| [102] | Q-learning | Collision, terminal state | Grid | No | Static | Multiple robots | Yes | Simulation |

| [100] | Q-learning | Distance | Grid | No | Static | Multiple robots | Yes | Simulation |

| [105] | Q-learning | Turning rewards, dynamic priority, action replanning | Grid | No | Static | Multiple robots | Yes | Simulation |

| [98] | Q-learning | Convergence, path length | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Multiple robots | Yes | Simulation, Experiment |

| [99] | Q-learning | Target, obstacles | Grid | No | Static | Single robot | No | Simulation |

| [101] | Q-learning | Locations, destinations | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Multiple robots, production logistics system | Yes | Simulation, Experiment |

| [104] | Q-learning, ACO, GA | Distance, congestion time, charging priority | Grid | No | Static | Single robot, shared charging system | Yes | Simulation |

| [103] | Q-learning, beetle antennae search (BAS) | Path length, average time | Grid | No | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [106] | Deep Q-learning | Obstacles, target | Grid | No | Static | Single robot, intelligent manufacturing workshops | Yes | Simulation |

| [95] | PPO, LSTM | Distance, heading angle, collision, target point | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot | Yes | Simulation, Experiment |

| [93] | PPO | Static and dynamic obstacles | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [92] | PPO, LSTM | Distance, collision | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [94] | MAPPO, GNN | Position, velocity, obstacle | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Multiple robots | Yes | Simulation |

| [96] | MAPPO | Movement, obstacles, global path, target, boundary | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [107] | DDPG, APF | Smoothness and safety | Graph | No | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [111] | DRL | Collision, movement, finish task | Grid | Yes | Static | Multiple robots | Yes | Simulation |

| [112] | Dyna-Q | Goal | Grid | Yes | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [110] | Dyna-Q, ACO | Obstacle, target | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [109] | SAC | Obstacle, distance, target and time | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [108] | MADDPG | Position, collision, speed | Grid | No | Static | Multiple robots | Yes | Simulation |

| [90] | D3QN, A* | Average tardiness and energy consumption | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Multiple robots | Yes | Simulation |

| [88] | DQN | Direction, steps, end point | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [89] | Dueling DQN | Position, velocity, target | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot, intelligent logistics systems | Yes | Simulation |

| Paper | Algorithm | Consideration | Model | Online | Properties | Scenario | Hybrid | Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [113] | Fuzzy logic, ACO | Pollutant emissions, fuel cost, travel time, and distance | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [114] | Fuzzy logic, APF | Obstacles, velocities, lane lines | 2D map | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot, automated terminals, port | Yes | Simulation |

| [115] | Fuzzy control, ACO, DWA | Safety, smoothness, distance, direction | Grid | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [116] | Fuzzy control, A*, DWA | Path length, path search, smoothness | Grid | Yes | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| Paper | Classification | Algorithm | Consideration | Model | Online | Properties | Scenario | Hybrid | Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [118] | Swarm intelligence | Jaya | Minimize transportation cost, total tardiness, early service penalty | Grid space | No | Static | Multi-robots, matrix manufacturing workshop | No | Simulation |

| [123] | Swarm intelligence | Artificial fish swarm algorithm | Safety, fuel economy, trajectory smoothness | Grid space | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot | Yes | Simulation, Experiment |

| [119] | Swarm intelligence | Fireworks algorithm, APF | Safety, path smoothness | - | Yes | Dynamic | Single robot, driving | Yes | Simulation, Experiment |

| [120] | Swarm intelligence | Sparrow search algorithm | Risk degree, path acquisition time, distance value, total rotation angle value | Grid space | No | Static | Single robot | No | Simulation |

| [121] | Swarm intelligence | GWO, Kalman filter | Path smoothness and length, obstacle avoidance | Grid space | No | Static | Single robot | Yes | Simulation |

| [122] | Swarm intelligence | DE | Make span, collision | Workshop diagram | No | Static | Multi-robots | Yes | Simulation |

| [117] | Artificial intelligence | SVM | Path length | Grid | No | Static | Multiple robots | Yes | Simulation |

| Paper | Algorithm | Contribution | Limitation/Future Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| [2] | MOPSO | Formulate energy-efficient AGV path planning model, two solution methods | Energy consumption data acquisition, integration of transport task execution, multi-AGV system |

| [49] | MOPSO, DWA | Combines MOPSO and DWA for optimization challenges and dynamics | Environmental uncertainties, changing environmental conditions, real-world experiments |

| [46] | PSO | Crossover operation, mutation mechanism, local optimum problem | Multi-AGV system |

| [5] | PSO, SA | Get rid of local optima, accept new solution, and update local-oriented best value with a probability | Dynamic environment, multiple robots, moving obstacles |

| [48] | PSO, GWO | Local search technique | Not multi-objective optimization, real-time implementation, multi-robots, moving goal |

| [50] | PSO | Alpha and beta as two coefficients | Path prediction and learning capabilities, only static simple environment |

| [52] | PSO | Levy flight, inductive steering algorithm | Dynamic situation is simple |

| [53] | PSO, ACO | A collision avoidance factor, avoid road-section and node conflicts | Only static environment |

| [47] | PSO, CA | The cultural-PSO algorithm, dynamic adjust inertial weight | Real-world experiment |

| [54] | PSO, ACO | PSO-IACO, PSO optimizes initial parameters of ACO | Only static environment, lack of real-world experiment |

| [51] | PSO, Human optimization algorithm | PSO combines HLO | Multi robots, dynamic environment |

| [55] | ACO | Heuristic information, compare the similarity of the job, path planning and scheduling | Limited robustness, other manufacturing environments (flexible job-shop or flow shop) |

| [56] | ACO | Fallback strategy, valuation function, reward/penalty mechanism | The efficiency of the algorithm |

| [57] | ACO | Penalty strategy | Multiple robots, experiment |

| [58] | ACO | Initial pheromone concentration, improved state transition probability rule | Three-dimensional problem, multi-objective optimization, execution time |

| [60] | ACO, Dijkstra | ACO-DA | Multi-AGV conflicts |

| [61] | ACO, A* Multi-Directional algorithm | Reward policy | Dynamic moving obstacles |

| [62] | ACO, rolling window | The pheromone concentration | Optimization, convergence performance, the scope of application |

| [63] | ACO, RRT* | Fast-scaling RRT*-ACO | Only static environment |

| [64] | ACO | Step length, adaptive pheromone volatilization coefficient | Multi-AGVs’ conflict resolution |

| [65] | ACO | Hexagonal grid map model, the bidirectional search strategy | Global search optimization, grid map’s robustness, real-world application, efficiency |

| [66] | ACO | RL configures ACO parameters | Lack comparison analysis |

| [67] | ACO | Bloch coordinates of pheromones; a repulsion factor | Uncertain environments, task assignment, real automated logistics systems |

| [68] | ACO | Combines FOA and ACO | Lack comparison analysis |

| [59] | ACO, GWO | A modified ACO based on GWO, heuristic information, the pheromone model, and transfer rules | Only static environment, lack comparison analysis |

| [69] | ACO, DWA | Combine ACO and DWA | Focus on global path planning, and the static environment is not complex |

| [70] | ACO | Additional heuristic information, dynamic adjustment factor, Laplace distribution | Dynamic simulation and scheduling |

| [71] | ACO, GA | Non-uniform and directed distribution of initial pheromone, adaptive adjustment, parameter optimization by GA | Lack comparison |

| [72] | ACO | Prior time, the pheromone increment | Large-scale and changing tasks |

| [73] | GA, Dijkstra, time window | Global, local and random search strategies, optimize the number of AGVs | Dynamic scheduling and job sequencing problem |

| [74] | GA, PSO, fuzzy logic controller | Integrated scheduling and path planning, adaptive auto tuning | Computation time, dynamic real-time scheduling |

| [76] | GA, heuristic | Applying the fuzzy linear programming, hybrid approach | Complicate AGVs’ constraints, not real case |

| [77] | GA, EDA | Cooperative path planning model, online adjustment strategy | More possible applications |

| [78] | GA, SA | Path smoothness constraints, crossover stage, mutation operation | Lacks comparison with state-of-the-art techniques |

| [79] | GA | Fitness function | Only consider static obstacles |

| [80] | GA, A* | A* combines cyclic rules, GA with penalty function | Only static obstacle, AGV charging problem in the future |

| [75] | GA | A three-stage optimal scheduling algorithm | Lacks comparison analysis, AGV charging, collision avoidance route |

| [81] | GA | Improved GA, two decision variables | Lacks comparison analysis |

| [118] | Jaya | The key-task shift method, initialization methods, offspring generation methods, insertion-based repair method | Considers more practical constraints and production environments, the use of multi-objective optimization problem and new techniques |

| [123] | Artificial fish swarm algorithm | Trail-based forward search algorithm, command signals | Lacks comparison with state-of-the-art techniques |

| [119] | Fireworks algorithm, APF | DynEFWA-APF | Incorporates personalized driving style |

| [120] | Sparrow search algorithm | Location update formula, neighborhood search strategy, linear path strategy | Experiment, multi-robots, dynamic obstacles |

| [121] | GWO, Kalman filter | Refine with KF corrections | Only static environment |

| [122] | DE | Hybrid variable neighborhood DE | AGVs’ speed, multi-objective optimization |

| Paper | Algorithm | Contribution | Limitation/Future Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| [82] | Neural network, the Bellman–Ford algorithm, a quadratic program | Offline training, and online path planning | Hard to acquire perfect situational awareness, trained data, dimensionality |

| [83] | RDNN, LSTM | RNDD-based motion planning, transfer learning strategies | Multi-robot environment |

| [84] | Neural network, ACO | Combines ACO with neural networks | The environmental model is not clear |

| [85] | NAR neural network, A* | Reduced and non-reduced point | The success rate is fair |

| [44] | Deep neural network (DNN), | Target area adaptive RRT*, optimal path backward generation, DNN | Consider kinematic information, 3D scenarios, and transfer learning in future studies |

| [113] | Fuzzy logic, ACO | FLACO, local optimum trap, global optimal path | Reducing the computing time, multiple vehicles |

| [114] | Fuzzy logic, APF | Hybrid APF-fuzzy model prediction controller | AGV modeling |

| [115] | Fuzzy control, ACO, DWA | Improved ACO and DWA with fuzzy controllers | Only static obstacles |

| [116] | Fuzzy control, A*, DWA | Adapative neuro-fuzzy inference system, enhanced A* with DWA | Robustness, applicability, real-world environments |

| [87] | RL DQN, A* | Slow convergence and excessive randomness | Local path planning |

| [86] | DQN | State-dynamic network model | Multi-AGV environment |

| [91] | DRL, RNN, PPO, LSTM | Temporary changes | Reduce the computational time, dynamic conflict avoidance strategies |

| [97] | Q-Learning | Global Q-learning path planning | Lack the modification of Q-learning |

| [102] | Q-learning | Behavior trees | Not considering completed situations, AGV scheduling, or real-world system |

| [100] | Q-learning | Contract net protocol | The comparison analysis is weak; it only uses traditional Q-learning |

| [105] | Q-learning | Map training and action replanning | Dynamics of AGVs are not considered; the environment is simple |

| [98] | Q-learning | Kohonen Q-learning | Task scheduling and assignment |

| [99] | Q-learning | A deep learning factor | Static obstacle environment |

| [101] | Q-learning | Digital Twin-driven Q-learning | More complex situations, task allocation |

| [104] | Q-learning, ACO, GA | Q-learning and ACO, positive ant colony feedback mechanism | Only compared with Dijkstra and A* algorithm, static environment |

| [103] | Q-learning, beetle antennae search (BAS) | BAS-QL | Static obstacles |

| [106] | Deep Q-learning | Experience replay pool, network structure, neighborhood weighted grid modeling | Dynamic environments should be studied |

| [95] | PPO, LSTM | Introduce ICM and LSTM into PPO | The success rate decreases when dynamic obstacles moving fast or not follow regular patterns |

| [93] | PPO | Additional intrinsic rewards | Cannot guarantee safety in the training |

| [92] | PPO, LSTM | Sample regularization, adaptive learning rate | Lack environmental experiments |

| [94] | MAPPO, GNN | GNN with MADRL | Complex interactions and dynamic environment |

| [96] | MAPPO | A* for global guidance, MAPPO for local planning | Multi-robot scenario |

| [107] | DDPG, APF | APF, twin delayed DDPG | Lack environmental perception and testing, real experiment, and hard to implement in complex environment |

| [111] | DRL | Local observations | High density of obstacles |

| [112] | Dyna-Q | Heuristic planning | Lacks comparison with SOTA methods |

| [110] | Dyna-Q, ACO | Improved heuristic function of ACO, combines with Dyna-Q | Lacks comparison analysis |

| [109] | SAC | Sum-tree replay | Lacks experiments |

| [108] | MADDPG | ϵ-Greedy | Optimal value has not been established |

| [90] | D3QN, A* | Digital twin, prevent deadlock and congestion | Multi-resource production scheduling problems |

| [88] | DQN | A refined multi-objective reward function, the priority experience replay mechanism | Robust training methods, dynamic obstacle prediction modules, experimental design |

| [89] | Dueling DQN | Multimodal sensing information, prioritized experience reply | MARL |

| [117] | SVM | SVM-based model, replanning period | Model transfer methodology |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lin, S.; Wang, J.; Kong, X. Bio-Inspired Reactive Approaches for Automated Guided Vehicle Path Planning: A Review. Biomimetics 2026, 11, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010017

Lin S, Wang J, Kong X. Bio-Inspired Reactive Approaches for Automated Guided Vehicle Path Planning: A Review. Biomimetics. 2026; 11(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Shiwei, Jianguo Wang, and Xiaoying Kong. 2026. "Bio-Inspired Reactive Approaches for Automated Guided Vehicle Path Planning: A Review" Biomimetics 11, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010017

APA StyleLin, S., Wang, J., & Kong, X. (2026). Bio-Inspired Reactive Approaches for Automated Guided Vehicle Path Planning: A Review. Biomimetics, 11(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010017