A Bio-Inspired Data-Driven Locomotion Optimization Framework for Adaptive Soft Inchworm Robots

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Design Concept and Fabrication

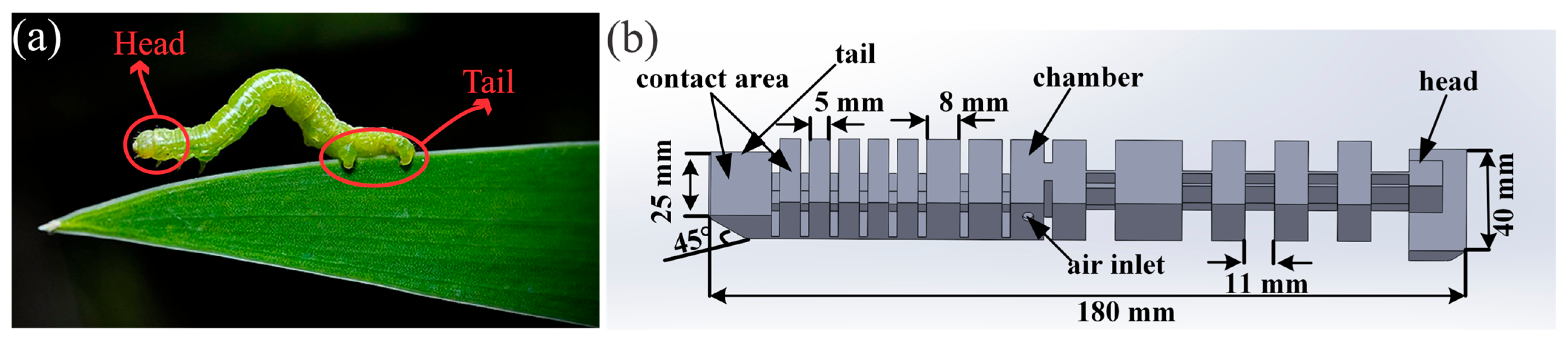

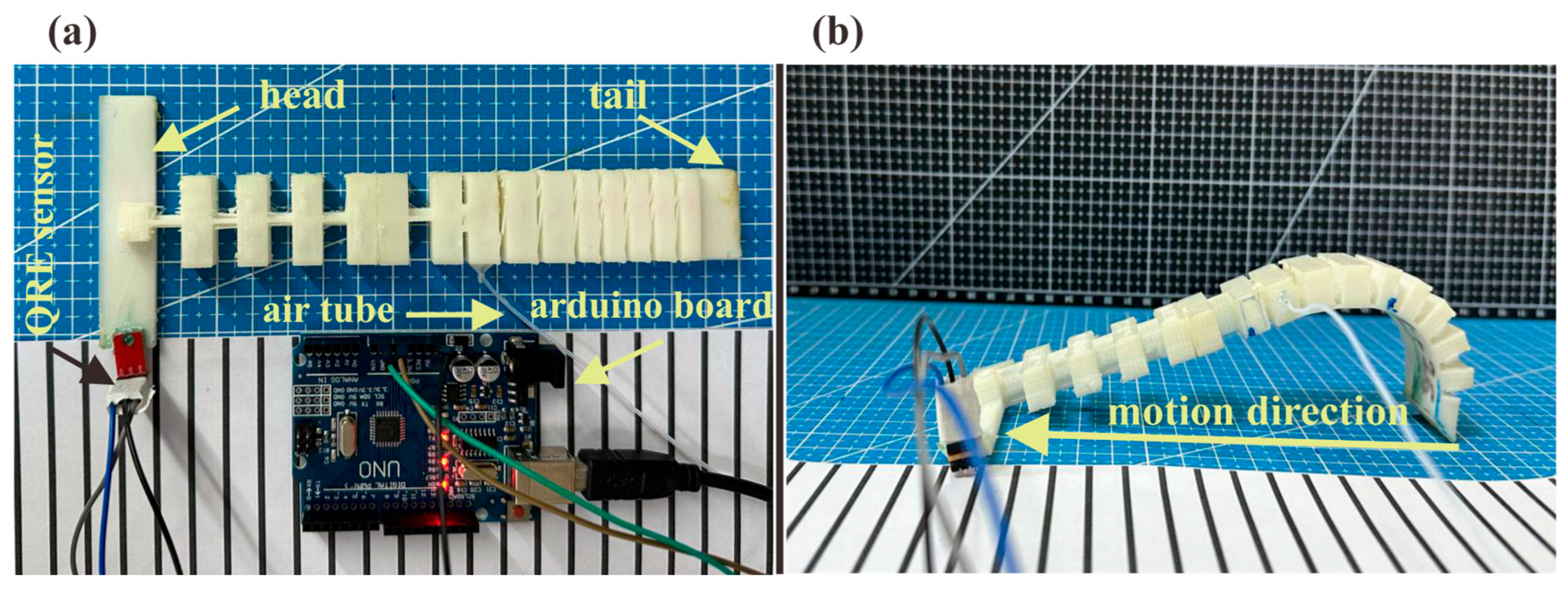

3.1. Bioinspired Inchworm Design and Locomotion Mechanism

3.2. Data Preparation and Processing

3.3. Sensor Operation and Velocity Calculation

4. Methodology

4.1. Dataset Overview and Evaluation of Traditional Machine Learning Models

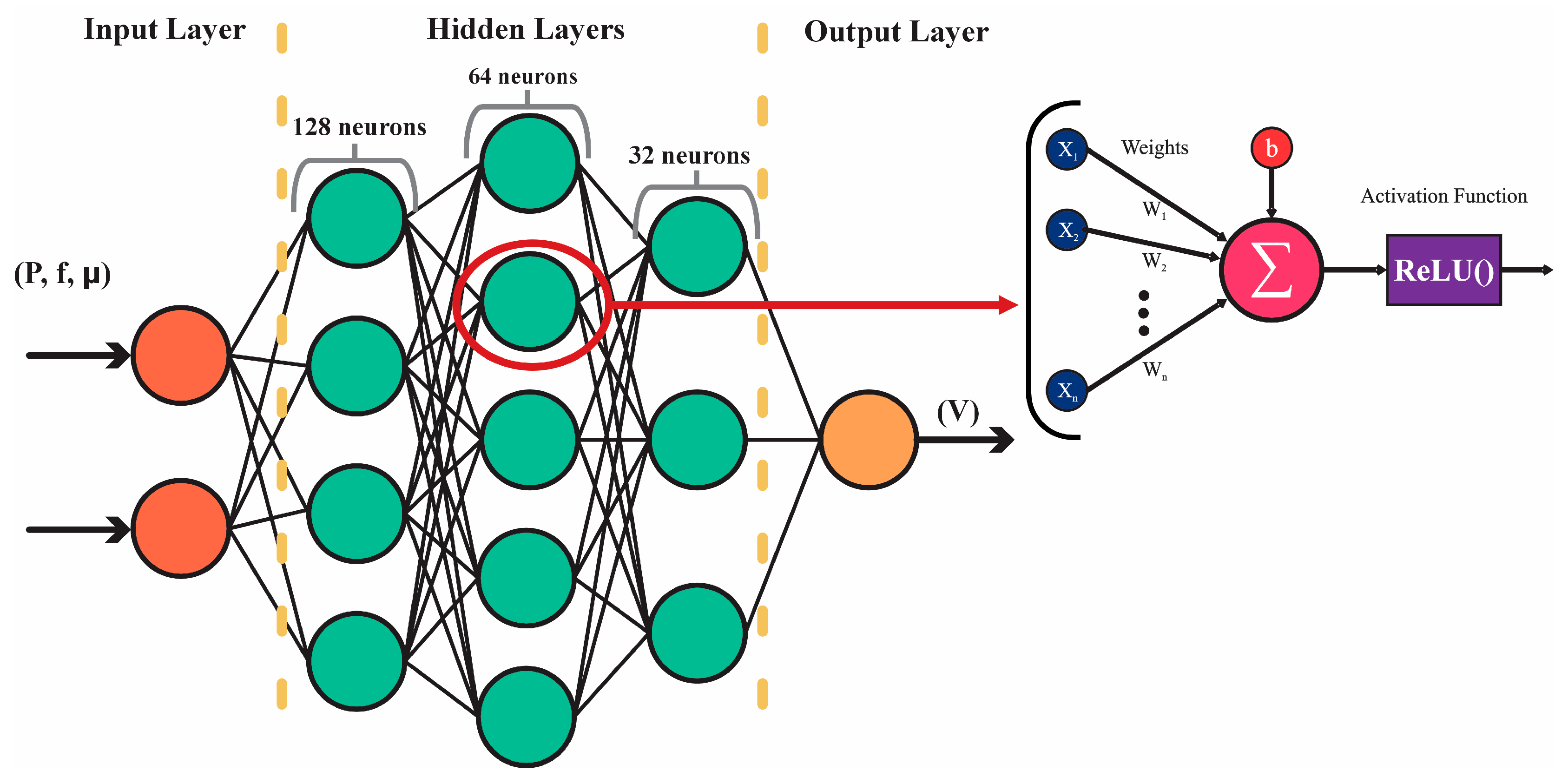

4.2. Predictive Neural Network Framework for Energy-Optimized Locomotion

5. Energy Efficiency Optimization

5.1. Surface-Specific Energy Optimization via Velocity-to-Pressure Ratio Maximization

| Algorithm 1. Surface-Specific Energy Optimization via PSO |

| 1: for each surface material do |

| 2: ←friction coefficient of surface m |

| 3: Initialize swarm with particles randomly in () |

| 4: for each particle do |

| 5: Predict velocity: ← |

| 6: Compute efficiency: |

| 7: Store personal best: |

| 8: end for |

| 9: Set global best ← particle with highest |

| 10: for do |

| 11: for each particle do |

| 12: Update velocity and position using PSO rules |

| 13: Ensure () remain within bounds |

| 14: Predict velocity: ← |

| 15: Compute efficiency: |

| 16: if then |

| 17: Update |

| 18: end if |

| 19: end for |

| 20: Update ← best among all |

| 21: end for |

| 22: Store optimal (f*, P*) for surface |

| 23: end for |

5.2. Adaptive Pressure Optimization Locomotion via Surrogate-Assisted PSO

| Algorithm 2. Frequency-Wise Adaptive Pressure Optimization via Surrogate-Assisted PSO |

| 1: for each surface material do |

| 2: friction coefficient of surface m |

| 3: for each frequency do |

| 4: Initialize swarm with particles in |

| 5: for each particle do |

| 6: Predict velocity: ← |

| 7: Compute cost: |

| 8: Store personal best: |

| 9: end for |

| 10: Set global best particle with lowest cost |

| 11: for do |

| 12: for each particle do |

| 13: Update velocity using PSO rule |

| 14: Ensure remains in bounds |

| 15: Predict velocity: ← |

| 16: Compute cost: |

| 17: if then |

| 18: Update |

| 19: end if |

| 20: end for |

| 21: Update best among all |

| 22: end for |

| 23: Store optimal pressure for current frequency |

| 24: end for |

| 25: end for |

6. Result and Discussion

6.1. Efficiency Analysis Across Materials

6.2. Adaptive Pressure and Frequency Optimization for Material-Specific Locomotion Using PSO

7. Conclusion and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Youssef, S.M.; Soliman, M.; Saleh, M.A.; Elsayed, A.H.; Radwan, A.G. Design and control of soft biomimetic pangasius fish robot using fin ray effect and reinforcement learning. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Renda, F.; Gall, A.L.; Mocellin, L.; Bernabei, M.; Dangel, T.; Ciuti, G.; Cianchetti, M.; Stefanini, C. Data-Driven Methods Applied to Soft Robot Modeling and Control: A Review. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 2241–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrile, S.; López, A.; Barrientos, A. Use of Finite Elements in the Training of a Neural Network for the Modeling of a Soft Robot. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akurda, T.; Trojanová, M.; Pomin, P.; Hošovský, A. Deep Learning Methods in Soft Robotics: Architectures and Applications. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 2400576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortman, V.; Mazzolai, B.; Sakes, A.; Jovanova, J. Perspectives on Intelligence in Soft Robotics. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 7, 2400294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, S.; Banerjee, H.; Tse, Z.; Ren, H. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Soft, Flexible Robots: Brief Review with Impending Challenges. Robotics 2019, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, T.; Kang, B.B.; Lee, M.; Park, W.; Ku, S.; Kim, D.; Kwon, J.; Lee, H.; et al. Review of machine learning methods in soft robotics. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xia, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Tang, W.; Chen, J.; Gao, F.; Ma, L.; Liao, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Hysteresis-Aware Neural Network Modeling and Whole-Body Reinforcement Learning Control of Soft Robots. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.13582. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.; Zhai, X.; Xue, W.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, J.; Bodaghi, M.; Liao, W.H. Finite element analysis, machine learning, and digital twins for soft robots: State-of-arts and perspectives. Smart Mater Struct. 2025, 34, 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Wang, F.; Ren, S.; Cheng, X.; Wang, G.; Li, P. A Review on the Recent Development of Planar Snake Robot Control and Guidance. Mathematics 2025, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Even, S.H.; Gordon, H.; Yang, Y. Machine Learning-Driven Burrowing with a Snake-Like Robot. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Salagame, A.; Ramezani, A.; Wong, L. Hierarchical RL-Guided Large-scale Navigation of a Snake Robot. In Proceedings of the 2024 EEE/ASME (AIM) International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics, Boston, MA, USA, 15–19 July 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, X.; Chen, D.; Li, Z.; Tan, X. Back-stepping Experience Replay with Application to Model-free Reinforcement Learning for a Soft Snake Robot. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 7517–7524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, Y.; Shohdy, T.; Hassan, H.A.; Eshra, M.; Elmenawy, O.; Khalil, O.; Hussieny, E.H. Development of a PPO-Reinforcement Learned Walking Tripedal Soft-Legged Robot using SOFA. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.09242. [Google Scholar]

- Jitosho, R.; Lum, T.G.W.; Okamura, A.; Liu, K. Reinforcement Learning Enables Real-Time Planning and Control of Agile Maneuvers for Soft Robot Arms. In Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Robot Learning 2023, Atlanta, GA, USA, 6–9 November 2023; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Huo, J.; Su, H. Path planning with obstacle avoidance for soft robots based on improved particle swarm optimization algorithm. Intell. Robot. 2023, 3, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, P.; Johnson, C.C.; Killpack, M.D. Model Reference Predictive Adaptive Control for Large-Scale Soft Robot. Front. Robot. AI 2020, 7, 558027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zheng, X.; Qi, S. Motion Planning of an Inchworm Robot Based on Improved Adaptive PSO. Processes 2022, 10, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.; Hellebrekers, T.; Majidi, C. Machine Learning for Soft Robotic Sensing and Control. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2020, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessi, C.; Bianchi, D.; Stano, G.; Cianchetti, M.; Falotico, E. Pushing with Soft Robotic Arms via Deep Reinforcement Learning. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 6, 2300899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Wan, Z.; Sun, Y.; Skorina, E.H.; Tao, W.; Chen, F.; Gopalka, L.; Yang, H.; Onal, C.D. Motion Planning and Iterative Learning Control of a Modular Soft Robotic Snake. Front. Robot. AI 2020, 7, 599242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.C.; Quackenbush, T.; Sorensen, T.; Wingate, D.; Killpack, M.D. Using First Principles for Deep Learning and Model-Based Control of Soft Robots. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Hughes, J.; Wah, S.; Matusik, W.; Rus, D. Underwater Soft Robot Modeling and Control with Differentiable Simulation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 4994–5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gasoto, R.; Jiang, Z.; Onal, C.; Fu, J. Learning to Locomote with Artificial Neural-Network and CPG-based Control in a Soft Snake Robot. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA; 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Loo, J.Y.; Ding, Z.Y.; Baskaran, V.M.; Nurzaman, S.G.; Tan, C.P. Robust Multimodal Indirect Sensing for Soft Robots via Neural Network Aided Filter-based Estimation. Soft Robot. 2021, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ménager, E.; Peyron, Q.; Duriez, C. Toward the use of proxies for efficient learning manipulation and locomotion strategies on soft robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 8478–8485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Onal, C.D.; Fu, J. Reinforcement Learning of CPG-Regulated Locomotion Controller for a Soft Snake Robot. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 3382–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayama, Y.; Editorial Office; Furukawa, H.; Ogawa, J. Development of a Soft Robot with Locomotion Mechanism and Physical Reservoir Computing for Mimicking Gastropods. J. Robot. Mechatron. 2025, 37, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A.M.; Hurd, E.; Minai, A.A.; Kumar, M. DeepCPG Policies for Robot Locomotion. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2023, 15, 2108–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Dear, T.; Kelly, S.D. Dear, Deep Reinforcement Learning for Snake Robot Locomotion. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 9688–9695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S.M.; Tiryaki, A.; Karakol; Sitti, M. Learning Soft Millirobot Multimodal Locomotion with Sim-to-Real Transfer. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 6982–6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shintake, J.; Hayashibe, M. Deep Reinforcement Learning Framework for Underwater Locomotion of Soft Robot. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Asawalertsak, N.; Heims, F.; Kovalev, A.; Gorb, S.N.; Jørgensen, J.; Manoonpong, P. Frictional Anisotropic Locomotion and Adaptive Neural Control for a Soft Crawling Robot. Soft Robot. 2023, 10, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuruthel, T.G.; Shih, B.; Laschi, C.; Tolley, M.T. Soft robot perception using embedded soft sensors and recurrent neural networks. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4, eaav1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asawalertsak, N.; Manoonpong, P. Adaptive Neural Control with Online Learning and Short-Term Memory for Adaptive Soft Crawling Robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 4380–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadfar, M.; Feng, Y.; Song, K.-Y. Advancing Soft Robotics: A High Energy-Efficient Actuator Design Using Single-Tube Pneumatic for Bidirectional Movement. J. Mech. Des. 2025, 147, 043301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.-H.; Lim, K.-H. Vanishing Gradient Mitigation with Deep Learning Neural Network Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2019 7th International Conference on Smart Computing & Communications (ICSCC), Sarawak, Malaysia, 28–31 June 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

| Method/Model | Application Area | Key Advantages | Limitations/Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression/Lasso [7] | Simple modeling, baseline comparison | Interpretable, fast | Cannot capture nonlinearities in soft robot dynamics |

| Decision Tree/Random Forest [4] | Regression, state estimation | Handles nonlinearity, robust to noise | Overfitting, less effective with high-dimensional data |

| K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) [7] | Tactile sensing, regression | Non-parametric, easy to implement | Sensitive to noise, not scalable |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) [7] | Regression | Good for small, high-dim data | Limited for highly nonlinear, dynamic systems |

| Feedforward Neural Network (FNN) [4,7] | Kinematic/dynamic modeling | Captures nonlinear relationships, high accuracy | Requires more data, black-box |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [4,7] | Tactile/vision-based sensing | Feature extraction from spatial data, robust to noise | Needs large datasets, less suited for time-series |

| Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), LSTM, GRU [4,5,7] | Dynamic/temporal modeling | Handles time dependencies, memory, hysteresis | Training instability, data-hungry |

| Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) [4,5,7] | Adaptive locomotion, control | Learns optimal policies model-free, adapts to new tasks | Data-intensive, sim-to-real gap, slow training |

| Hybrid (Physics + ML) [23] | Modeling, sim-to-real transfer | Combines physical priors with data-driven adaptation | Integration complexity, limited scalability |

| CPG + RL Hybrid [4] | Gait generation, snake robots | Enables rhythmic, adaptive locomotion, reduces RL training | Needs careful tuning, still data-intensive |

| Reservoir Computing [4] | Tactile discrimination, adaptive control | Leverages soft material dynamics for computation | Limited to specific tasks, less explored in control |

| Gaussian Processes [23] | Uncertainty estimation, regression | Probabilistic, quantifies uncertainty | Not scalable to large datasets |

| Ref. | Robot/Application | Actuation System | Control Method | Modeling Approach | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | Pangasius fish | Servo-driven fin ray | Reinforcement learning (PPO, A2C, DQN tested and PPO) | Model-free RL; direct training on physical robot using pose estimation via DeepLabCut | RL enables the robot to: -Efficiently swim; -Handle complex underwater dynamics without explicit modeling; -Learn goal-reaching behavior on real hardware; -Robust, adaptive control in real aquatic settings. |

| [2] | Soft robots | Multiple | Machine learning (CNN, kNN, SVM, RNN) | Data-driven (large-scale tactile datasets, sensor fusion) | ML methods effectively: -Handle nonlinearity and hysteresis; -Support versatile sensing and robust interaction in diverse environments. |

| [3] | Soft bioinspired manipulator | Shape memory alloy | Open-loop (vision-based feedback for validation) | Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) neural network | Neural network enables: -Real-time kinematic modeling; -Reducing the need for extensive physical experiments; Providing fast, energy-efficient direct kinematic solutions. |

| [4] | Soft robots (review, ML techniques) | Multiple | Machine learning (RNN, hybrid, various) | Data-driven (recurrent/hybrid models) | RNNs and hybrid models: -Capture temporal nonlinearities and dynamics; -Learning-based methods improve real-time modeling; -Control and design optimization in soft robotics. |

| [6] | Various soft robot | Multiple | Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) and imitation learning (IL) methods including DQN, DDPG, A3C, PPO, GAIL, behavioral cloning, and inverse RL | Model-free (policy/value-based RL, actor-critic, meta-learning), neural networks (CNNs, RNNs), generative models (GANs) | DRL/IL methods enable: -Learning complex, high-DOF soft robot control; -Overcoming the need for explicit analytical models -Meta-learning and imitation learning reduce data requirements and improve real-world deployment; |

| [8] | Soft robot for laparoscopic surgical operations | Pneumatic actuation | Reinforcement learning (on-policy, proximal policy optimization—PPO) | Neural network (HWB-NN): multilayer perceptron (MLP) with 6D input | -Captures and predicts whole-body morphology including hysteresis effects; -Reduces MSE by 84.95% vs. traditional models -Enables high-precision (0.126–0.250 mm error) real-world trajectory tracking; |

| [11] | Snake bio-inspired robot | Batteries | Sequence-based deep learning (1D CNN + LSTM), optimized with truncated Newton conjugate-gradient (TNC) | LSTM attention layers, sequence-based model | -Learns efficient adaptive burrowing strategies in highly nonlinear uncertain granular environments. |

| [12] | Snake soft robot | Motors | Local navigation (RL), gait generation (CPG), gait tracking (PID) | RL (DDPG) tunes CPG parameters for local navigation; CPG generates rhythmic PID tracks joint | -RL-CPG scheme enables fast, transferable learning for high-DOF robots; -Dramatically reduces RL training time. |

| [13] | Pneumatic soft snake robot | Pneumatic actuation | Model-free reinforcement learning (DDPG, with back-stepping experience replay—BER) | - | -Robust to random target navigation; -Compatible with arbitrary off-policy RL. |

| [14] | Tripedal soft-legged robot | Tendon-driven | Model-free reinforcement learning (Proximal Policy Optimization, PPO) | Gym environment for RL integration; reward function penalizes instability | -PPO enables learning stable, adaptive walking and navigation without explicit modeling of soft body dynamics; -Achieves 82% success rate in random goal-reaching and 19 mm path deviation on trajectory following; |

| [15] | Inflated-beam soft robot arm | Pneumatic actuation | Deep reinforcement learning (PPO) | Neural network composed of a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) | -Enables real-time, agile, and highly dynamic maneuvers; -Neural network architecture (MLP + LSTM) allows the policy to leverage temporal information and handle partial observability. |

| [18] | Soft-rigid hybrid biomimetic fish robot | Servo-driven fin ray | Model-free reinforcement learning (tested PPO, A2C, DQN; PPO) | RL environment built with OpenAI Gym and Stable Baselines3; observation space from real-time pose estimation using DeepLabCut | RL enables the robot to: -Autonomously learn efficient swimming policies for goal-reaching in a real aquatic environment. |

| [20] | Soft continuum manipulators | Pneumatic actuation | Supervised learning (for sensing, kinematics, dynamics), reinforcement learning (for direct control) | Neural networks (feedforward, convolutional, recurrent/LSTM, deep NN) | ML enables modeling and control of highly nonlinear, high-DOF, and hysteretic soft systems where analytical models are intractable; neural networks can encode dynamic behaviors, adapt to nonstationarity; |

| [21] | Soft robotic arm | Pneumatic actuation | Deep reinforcement learning (proximal policy optimization—PPO) with closed-loop pose/force control | Dynamic Cosserat rod model with domain randomization in simulation | -Enables sim-to-real transfer for dynamic interaction tasks; -Achieves pose and force control without explicit force input. |

| [25] | Soft snake robot | Pneumatic actuation | Hybrid: model-free reinforcement learning (PPOC) regulates a central pattern generator (CPG) network (Matsuoka oscillators) | Matsuoka CPG network | -Adaptive RL with stable and diverse CPG-based enables efficient learning in motion. |

| [26] | Robotic grasping | - | Deep learning-based control (using DNNs) | Deep neural networks (DNNs) | DNNs can learn directly from raw sensor data, extract features without manual engineering, integrate high-dimensional and multimodal data, and adapt to unstructured environments. |

| [29] | General robotics | - | Deep learning-based control (including reinforcement learning, policy learning, perception-action loops) | Deep neural networks (DNNs), including CNNs, RNNs, autoencoders, and policy networks | DNNs can process raw, high-dimensional sensor data without manual feature engineering, enable sensor fusion, learn complex nonlinear mappings, and adapt to unstructured environments. |

| [32] | snake robots | Motor-driven joints | Deep reinforcement learning (DQN) | Geometric mechanics-based kinematic models; model-free RL (DQN) | Enables automatic discovery of efficient novel gaits for both land and water without human-designed trajectories. |

| [34] | Grasping robot | - | Deep learning (various DNN structures | Deep neural networks (DNNs) | DNNs can learn directly from raw sensor data, extract features without manual engineering, fuse multimodal inputs, and adapt to unstructured environments. |

| Model | MAE | MSE | RMSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | 0.6708 | 0.7385 | 0.8593 | 0.6035 |

| Lasso Regression | 0.6715 | 0.7719 | 0.8786 | 0.5856 |

| Decision Tree | 0.3704 | 0.3324 | 0.5765 | 0.8215 |

| KNN | 0.6600 | 0.9075 | 0.9527 | 0.5128 |

| SVR | 0.6352 | 0.8026 | 0.8959 | 0.5691 |

| Random Forest | 0.4414 | 0.3387 | 0.5820 | 0.8181 |

| Bagging | 0.3379 | 0.3867 | 0.6219 | 0.7924 |

| Neural Network | 0.2177 | 0.1520 | 0.3898 | 0.9362 |

| Method | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Linear Regression | Intercept: Included Robust: false (ordinary least squares) |

| Lasso Regression |

|

| Decision Tree |

|

| KNN |

|

| SVR |

|

| Random Forest |

|

| Bagging |

|

| Neural Network |

|

| No. | 1st Layer Neurons | Dropout | 2nd Layer Neurons | 3rd Layer Neurons | MAE | MSE | RMSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32 | 0 | 64 | 32 | 0.2571 | 0.1692 | 0.4113 | 0.9289 |

| 2 | 32 | 0.1 | 64 | 32 | 0.2801 | 0.2277 | 0.4772 | 0.9044 |

| 3 | 32 | 0.2 | 64 | 32 | 0.4267 | 0.4097 | 0.6401 | 0.8279 |

| 4 | 128 | 0 | 64 | 32 | 0.2198 | 0.1608 | 0.401 | 0.9325 |

| 5 | 128 | 0.1 | 64 | 32 | 0.2177 | 0.1520 | 0.3898 | 0.9362 |

| 6 | 128 | 0.2 | 64 | 32 | 0.2218 | 0.1600 | 0.4000 | 0.9328 |

| Experiment | Objective | Surface Materials | Varied Parameters | Evaluation Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 | Maximize energy efficiency (velocity-to-pressure ratio) | iron, glass, acrylic, paper, rubber | Pressure, frequency | Maximum v/P ratio |

| Exp. 2 | Minimize required pressure for stable velocity | iron, glass, acrylic, paper, rubber | Pressure (per frequency) | Minimum pressure for stable motion |

| Material | Optimal Pressure (kPa) | Optimal Frequency (Hz) | Predicted Velocity (cm/s) | Efficiency (cm/kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | 204.18 | 0.4 | 4.4342 | 0.0217 |

| Rubber | 228.68 | 0.4 | 3.7667 | 0.0165 |

| Acrylic | 235.86 | 0.4 | 5.2706 | 0.0223 |

| Paper | 250 | 0.4 | 1.3856 | 0.0055 |

| Glass | 232.35 | 0.4 | 3.7592 | 0.0162 |

| Frequency | 0.125 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | FMRMP | 113 | 113 | 111 | 108 | 113 |

| BMRMP | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Rubber | FMRMP | 169 | 103 | 191 | 102 | 168 |

| BMRMP | 147 | -- | 180 | 119 | 104 | |

| Acrylic | FMRMP | 100 | 100 | 118 | 138 | 109 |

| BMRMP | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Paper | FMRMP | 231 | 201 | 182 | 194 | 219 |

| BMRMP | 127 | 145 | 147 | 140 | 154 | |

| Glass | FMRMP | 231 | 165 | 129 | 100 | -- |

| BMRMP | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- | 110 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Behzadfar, M.; Karimpourfard, A.; Feng, Y. A Bio-Inspired Data-Driven Locomotion Optimization Framework for Adaptive Soft Inchworm Robots. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10050325

Behzadfar M, Karimpourfard A, Feng Y. A Bio-Inspired Data-Driven Locomotion Optimization Framework for Adaptive Soft Inchworm Robots. Biomimetics. 2025; 10(5):325. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10050325

Chicago/Turabian StyleBehzadfar, Mahtab, Arsalan Karimpourfard, and Yue Feng. 2025. "A Bio-Inspired Data-Driven Locomotion Optimization Framework for Adaptive Soft Inchworm Robots" Biomimetics 10, no. 5: 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10050325

APA StyleBehzadfar, M., Karimpourfard, A., & Feng, Y. (2025). A Bio-Inspired Data-Driven Locomotion Optimization Framework for Adaptive Soft Inchworm Robots. Biomimetics, 10(5), 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10050325