3. Results and Discussion

The kinematic parameters are selected to ensure effective simulation performance. The wavelength is fixed at

. The Strouhal frequency

and damping ratio

are varied in increments of

and

, respectively, within the ranges shown in

Table 3. The non-dimensional inertia

is adjusted in steps of

. The torsional spring stiffness for passive pitching depends on

,

n,

,

a, and

, as expressed in Equation (

5). Relevant kinematic parameters are summarized in

Table 3.

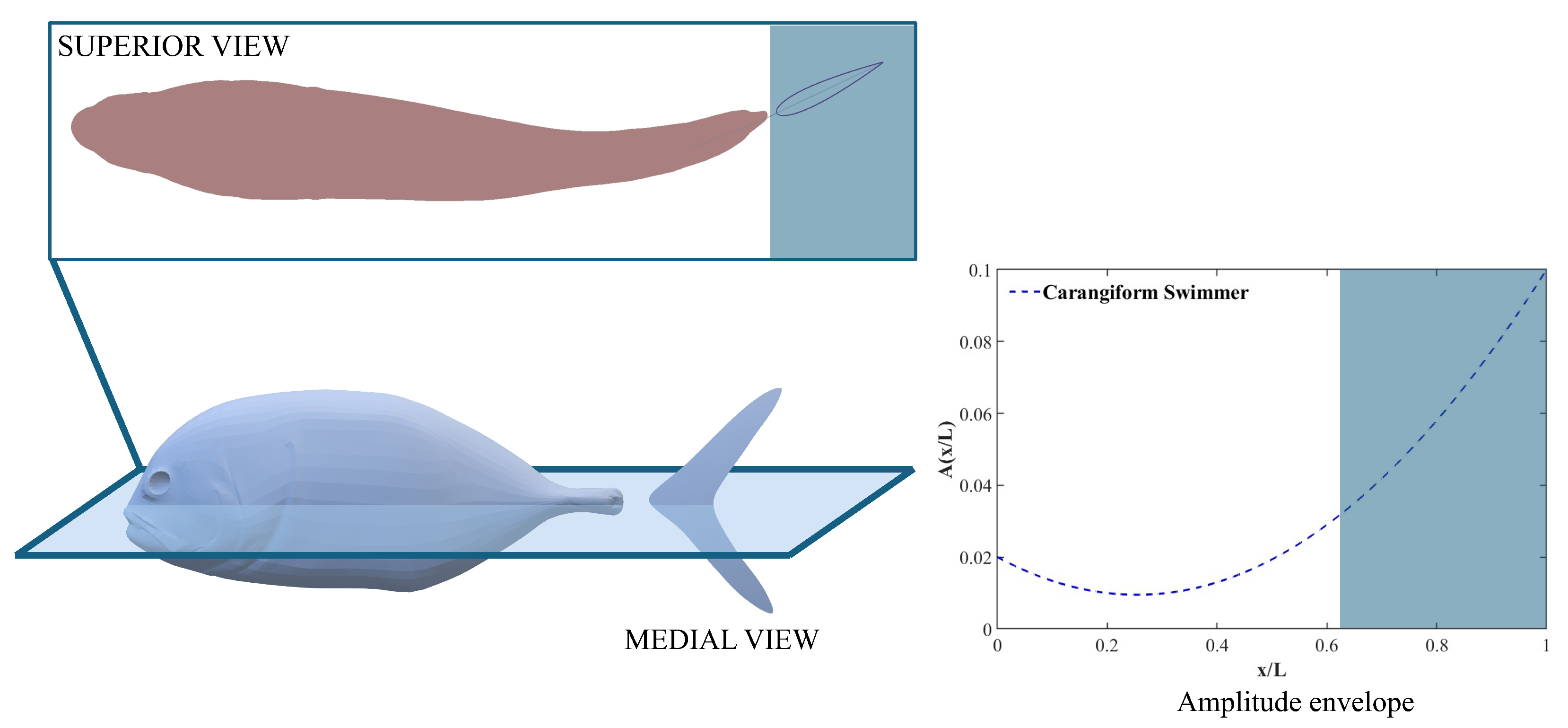

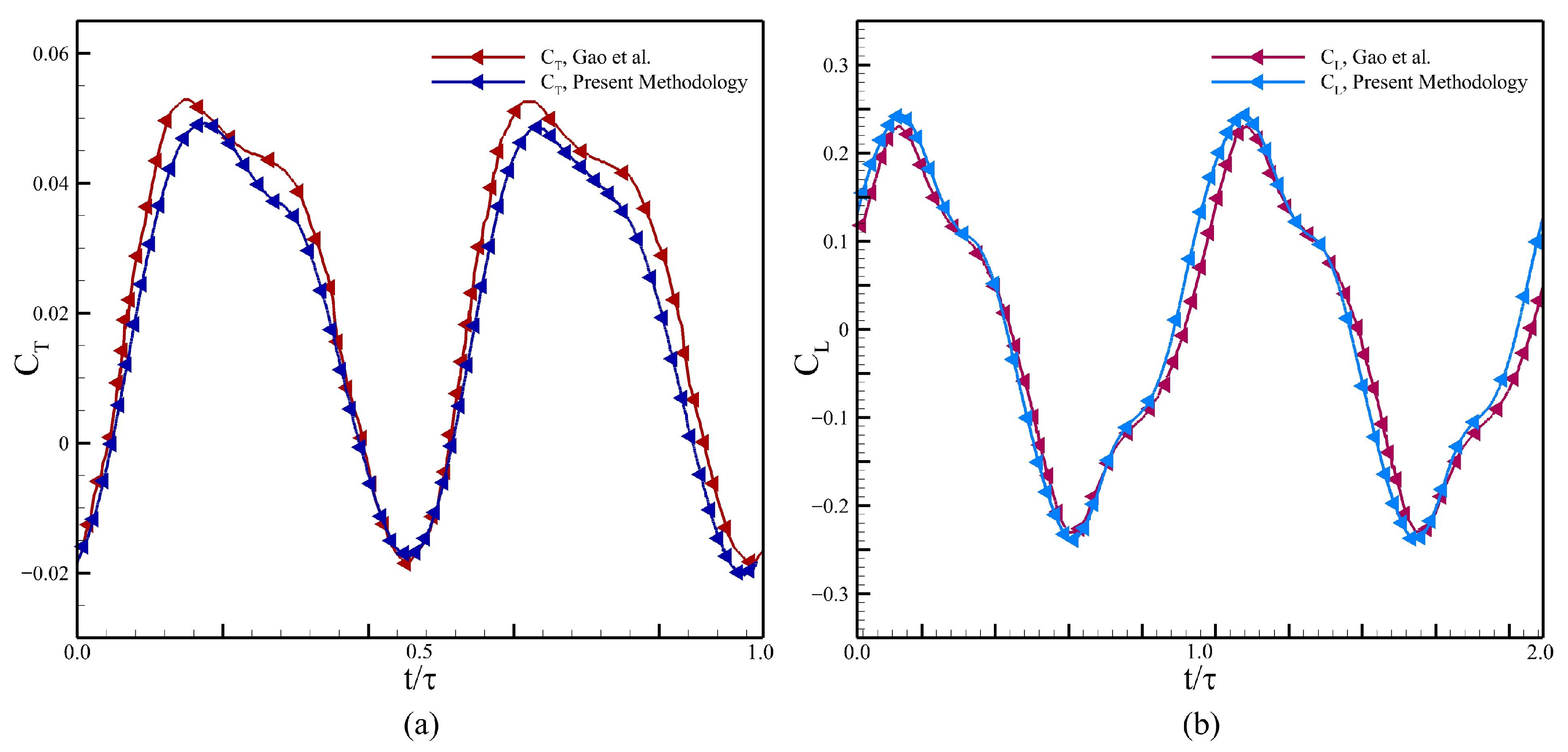

A common modeling approach approximates the body of a carangiform swimmer as a single airfoil [

10,

24,

25,

26,

31], as illustrated in

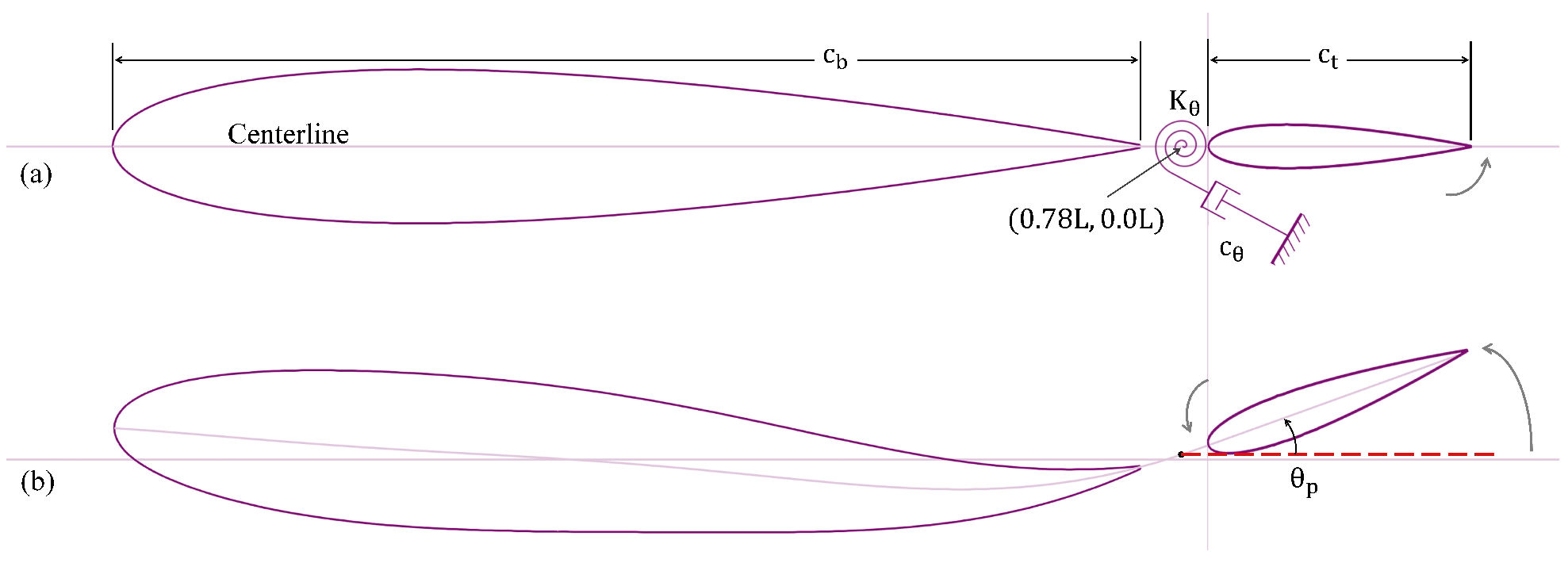

Figure 7a. In this study, we instead adopt a biomimetic two-foil configuration, representing the body and tail as separate foils, as shown in

Figure 7b. To ensure a consistent tail trajectory across all cases, the prescribed flapping motion is constrained so that the centerlines of the body and tail remain continuous. The amplitude trailing-edge amplitude of the tail is matched to the undulatory envelope of a carangiform swimmer at the posterior section of the body, with a maximum lateral amplitude of

. Since the geometry and flow conditions are identical for both the actively and passively pitching tails, a direct comparison can be made to evaluate how hydrodynamic performance changes when the kinematics of the tail are switched from active to passive. In this framework, the heaving displacement of the tail is prescribed to follow the undulation of the body at its peduncle, while the kinematics of the tail with active pitching is defined by Equation (

10).

where

denotes the angle.

For the actively pitching-tail configuration, a total of ten simulations are conducted at Re = 500 and Re = 5000, covering five Strouhal frequencies in the range

. The maximum pitching angle of the tail,

, is defined as the angle between the leading edge and the centerline at its peak within an oscillation cycle (see

Figure 7). The resulting motion produces a phase difference (

) of

between the heaving and pitching of the tail. The performance of the tail is evaluated in terms of the ratio between the output power and input power, expressed as a power ratio (

) defined by Equation (

11). The power coefficients

,

, and

are obtained from Equations (

12)–(

14), following the methodology of Picard et al. [

32] and Wu et al. [

33]. For the actively pitching cases, the

=

.

Here,

and

denote the heaving and pitching velocities of the tail, respectively. The normalized mean power consumed by the tail to heave (

) and pitch (

), alongside the output power (

) for the actively pitching tail, are computed at Re = 500 and Re = 5000. As summarized in

Table 4, the power-ratio

increases significantly between Re = 500 to 5000, indicating more favorable energy transfer at Reynolds number 5000. A consistent drop in

is observed at

for both Reynolds numbers, while a low value of power ratio (

) occurs at

and

, corresponding to negligible thrust output (

) as per the relationship from Equation (

11).

Table 5 presents the variation of the mean drag coefficient with an increasing

for the tail of the swimmer. The results show a clear transition from near-zero thrust at low

to increasingly negative values as the frequency rises, indicating a corresponding increase in thrust. Furthermore, at Re = 5000, the negative mean drag coefficient (positive thrust) is consistently larger in magnitude than at Re = 500, showing larger thrust generation at the higher Reynolds number.

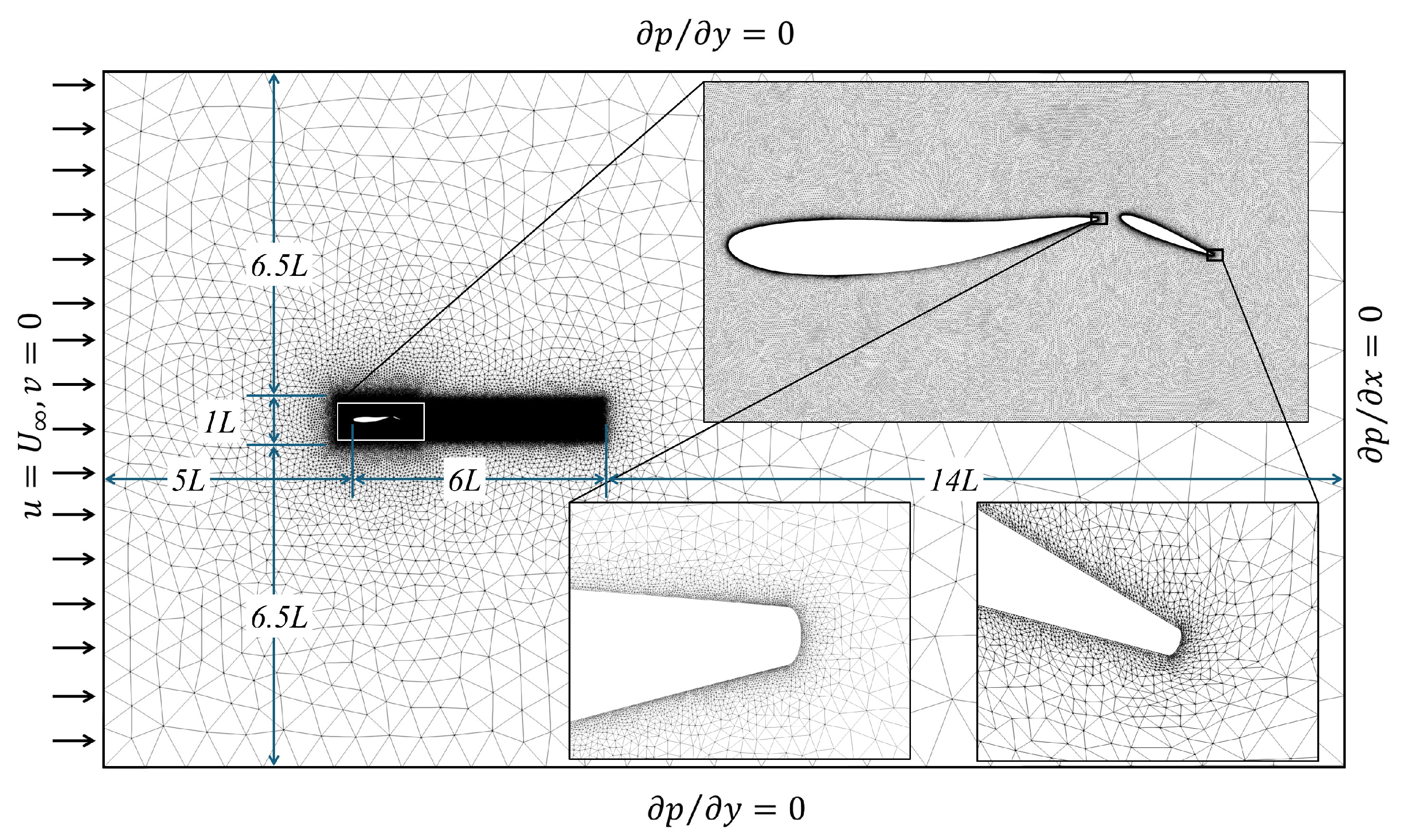

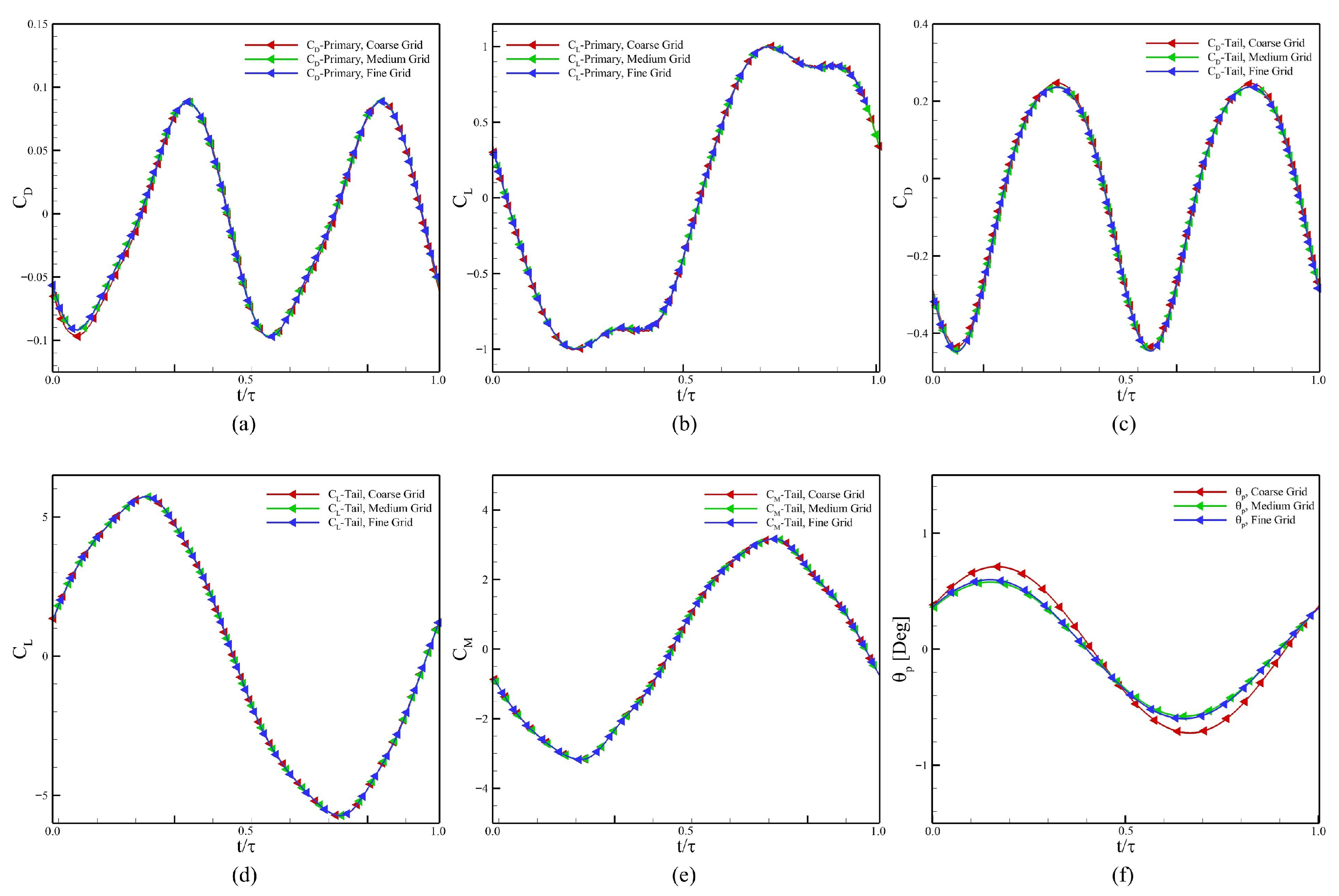

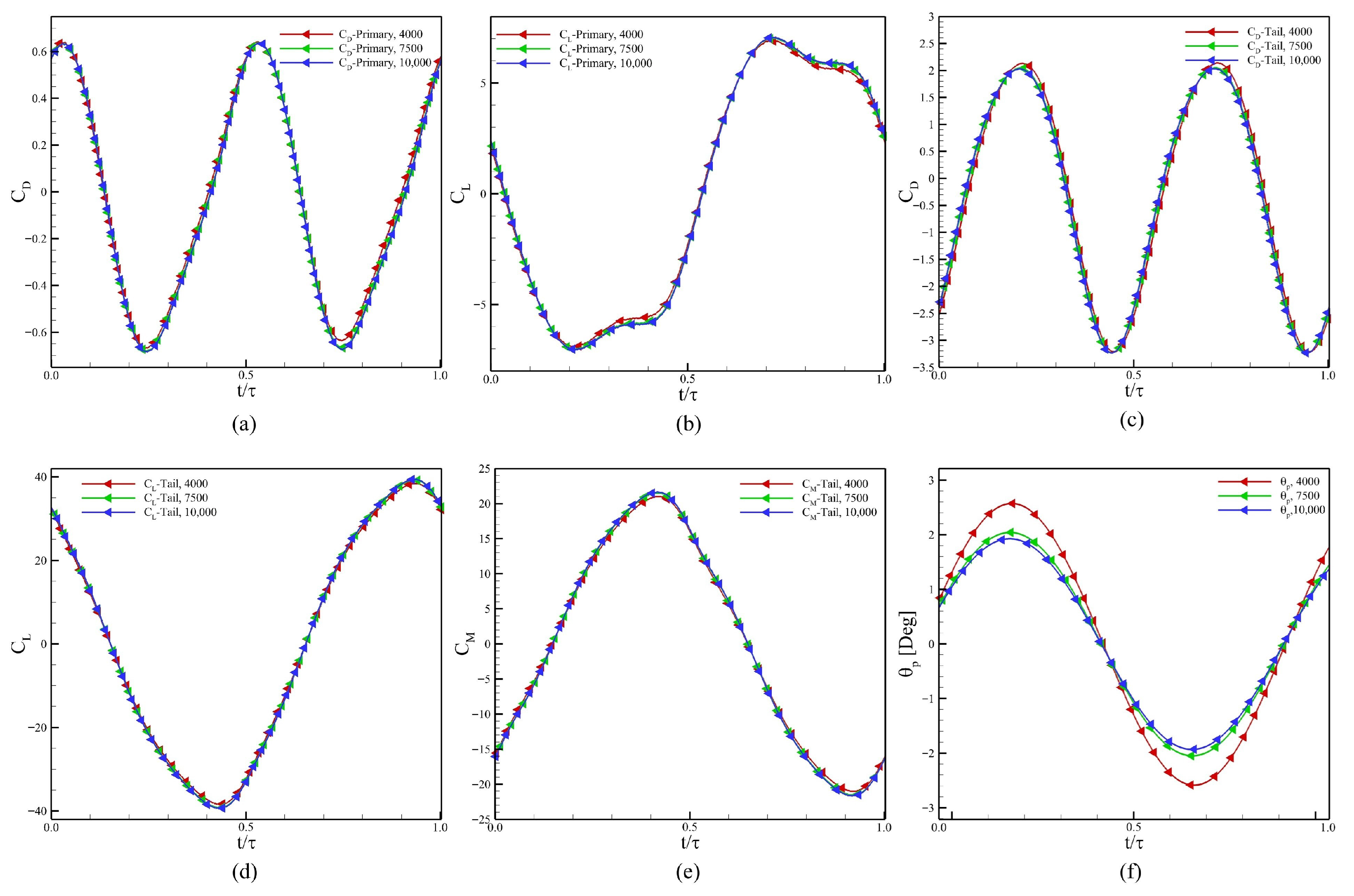

Before discussing the dynamics of the swimmer with a passively pitching tail, we note that a total of 150 numerical simulations are performed. The responses are categorized into three modes: stable drag-dominated, stable thrust-dominated, and unstable. This classification is summarized in

Figure 8, which we refer to as the stability maps, constructed for different sets of kinematic and flow parameters. The classification is based on 40 oscillation cycles. A case is considered stable if the flow reaches a periodic steady state within this window; otherwise, it is classified as unstable. Stability is determined using the drag coefficient (

): if a case fails to reach a steady state (

Figure 8h), the case is labeled as unstable, whereas cases that converge to steady periodic behavior (

Figure 8g) are labeled stable. Although steady state is typically achieved within 5–8 cycles, 40 cycles are simulated to ensure complete decay of transient effects and convergence to steady state. Stable cases are further categorized using the mean drag coefficient (

). If

, the case is classified as stable drag-dominated; if

, it is classified as stable thrust-dominated.

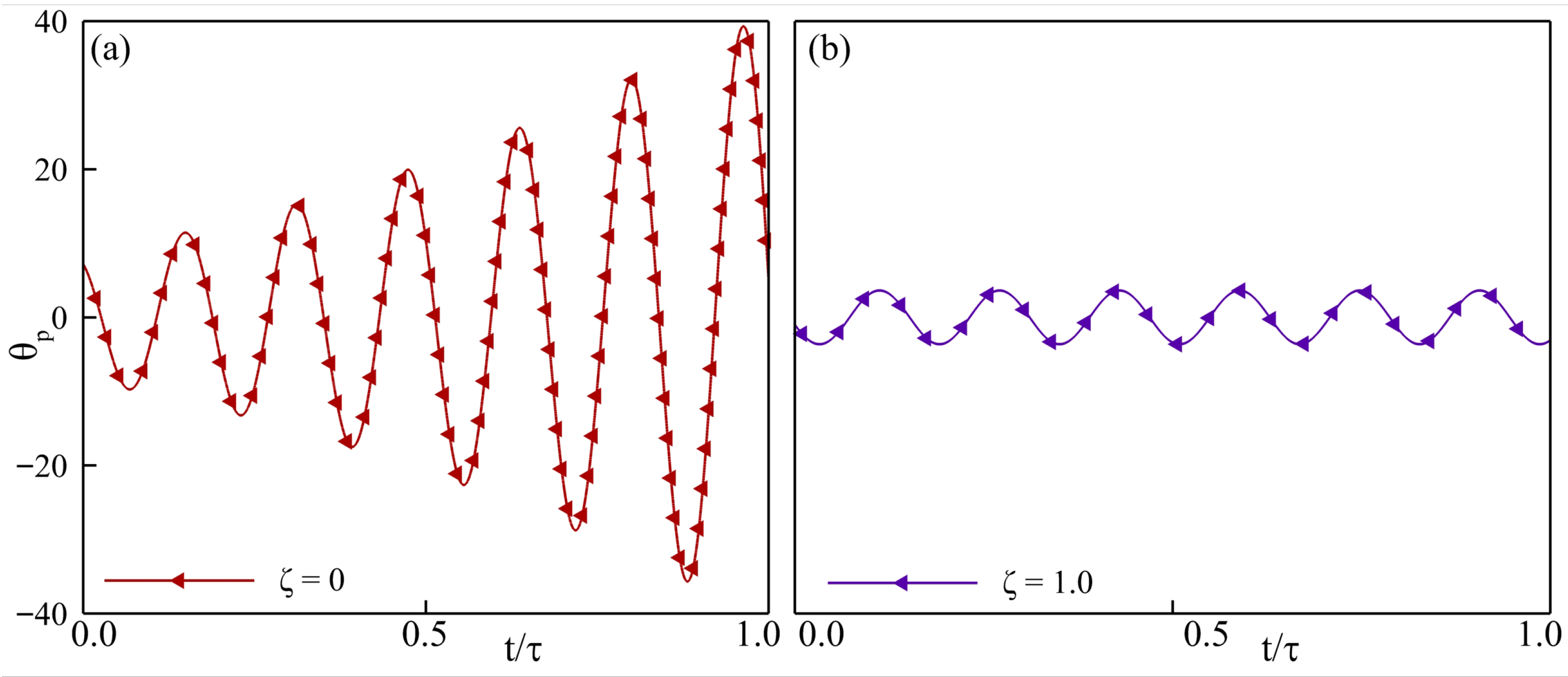

Across the stability maps, three clear patterns emerge. First, every undamped configuration (

) diverges, confirming the requirement of minimal damping needed for a bounded motion of the passively pitching tail. Profiles of the pitching angle for the configurations with

and

, shown in

Figure 9 for constant parameters

,

, and

, illustrate the effect of damping on the pitching response. In

Figure 9a, the pitching goes unbounded, which looks stabilized upon increasing the damping as shown in

Figure 9b. Introducing a light damping (

) causes the tail to drift in and out of the thrust-producing region, highlighted by the dashed rectangle in

Figure 8d, illustrating the decisive influence of fluid–structure coupling on the net force. At Re = 500, stability improves with a higher inertia, with the tail exhibiting a stable dynamic response at Re = 500, and in the majority of cases at Re = 5000. In these cases, the response becomes thrust-dominated, as the

increases from left to right. The consistent trends that we observe at Re = 500 do not stay true when the Reynolds number is changed to 5000. At Re = 5000, the trend of stable and unstable cases stays consistent at

and

, but the inconsistency based on the

is prominent at

and

.

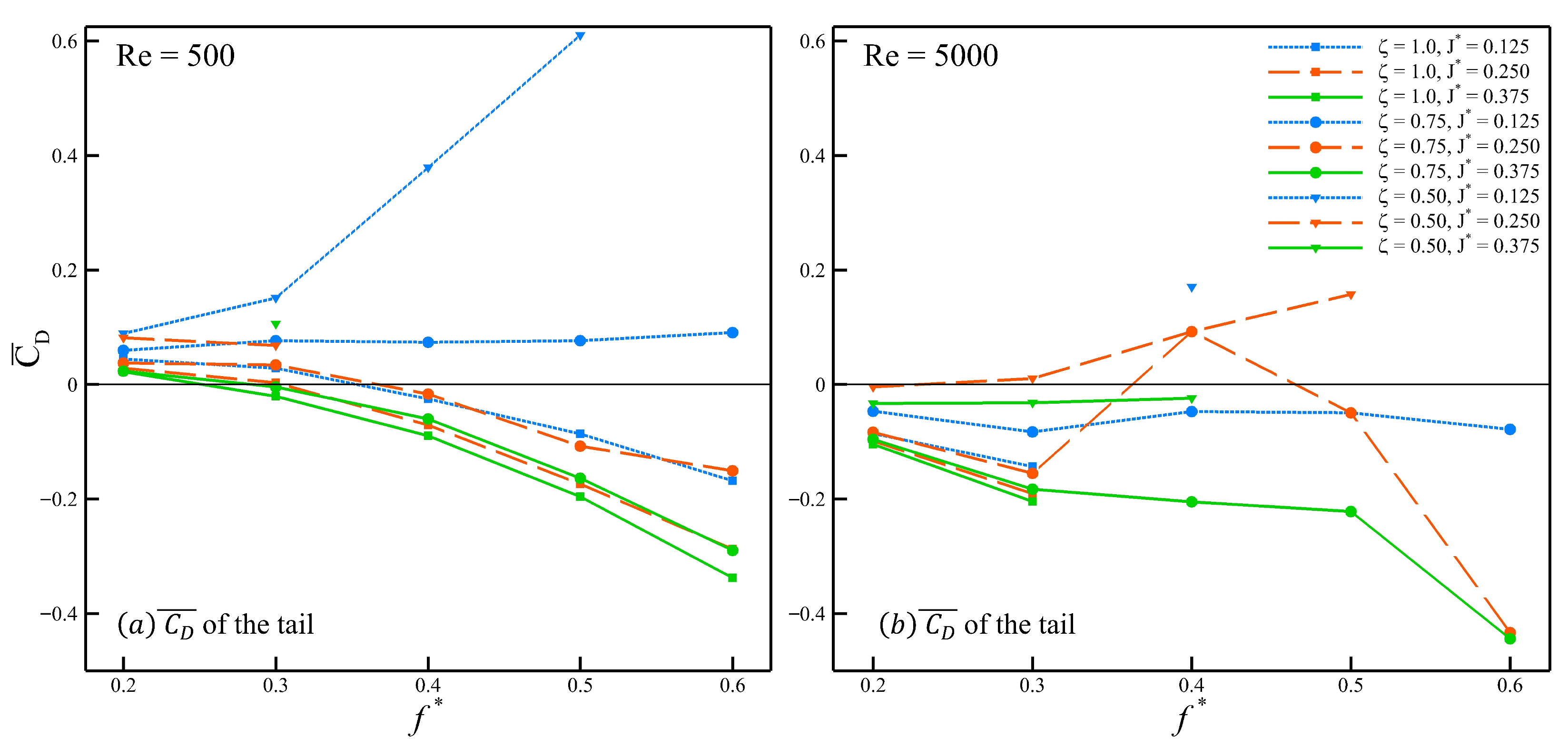

We now turn to the passively pitching tail and analyze its drag coefficient for all stable cases. It allows us to assess how the transition from active to passive pitching influences the performance of the swimmer, based on the mean drag coefficient presented in

Figure 10.

Figure 10a and

Figure 10b show the mean drag coefficient (

) of the tail at Re = 500 and Re = 5000, respectively. From

Figure 10a, the first observation is that the configuration with

and

exhibits an increasing

(i.e., decreasing thrust) as the

increases to

. Beyond this point, at

, the case becomes unstable. Secondly, for the same value of inertia (

) but with a higher

, the trend remains nearly constant across the range of Strouhal frequencies considered here. When this trend is compared to that of at

a large shift, increasing the damping ratio shows a reduction of

. Further increasing the damping ratio (

), the trend shows a behavior similar to that of the actively pitching tail where the thrust increases as the Strouhal frequency is increased. Finally, examining the stable cases with a passively pitching tail, at

for a range of inertia values (

–

), neither of the cases fully transition towards producing positive thrust (

). However, all of the cases display a reduction in drag with an increase in inertia, and this trend of drag reduction with a higher inertia is consistently observed for all damping ratios chosen for this work.

At Re = 5000 shown in

Figure 10b, the number of stable cases decreases, making it more difficult to identify clear trends and assess the effect of Strouhal frequency on the mean drag coefficient. Compared to the cases at Re = 500, the configurations that remain stable at Re = 5000 generally show better performance in terms of mean thrust. However, despite the improvement when the Reynolds number increases, the inconsistencies in the trends make it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the role of the Strouhal frequency. Based on the trends observed in

Figure 10a,b, the behavior of the swimmer about its peduncle can be interpreted by categorizing the tail into three types according to its inertia

. While the inertia defines the characteristic response of the tail itself, the damping ratio characterizes the nature of its joint to the body. A lower damping ratio corresponds to a more loosely joined and flexible body and tail connection, whereas a higher damping ratio indicates a stiffer and less flexible joint.

The nature of the joint between the body and the tail of the swimmer influences its thrust performance, as discussed earlier. From the previous analysis, a stiffer joint between the body and the tail corresponds to higher thrust or a more thrust-dominant behavior, whereas a more flexible or looser joint leads to a drag-dominant response.

Table 6 presents the maximum pitching angle (

) alongside the mean drag coefficient (

) of the tail at Re = 500 and Re = 5000 for all stable cases. The results are grouped in

Table 6a–e according to the Strouhal frequency (

–

). Here,

N/A indicates values that could not be evaluated due to the unstable nature of the configuration, as identified in the stability maps shown in

Figure 8a–f.

Analyzing the effect of Strouhal frequency, for a given configuration of and , an increase in leads to a larger maximum pitching angle (). It is accompanied by a clear trend of decreasing mean drag coefficient () or equivalently increasing thrust (), a behavior consistent at both Re = 500 and Re = 5000. However, when and are held constant to isolate the effect of , decreases alongside decreasing . A similar trend is observed when and are fixed and is varied. These observations suggest that a larger pitching amplitude is beneficial only when achieved by increasing the Strouhal frequency. In contrast, when the larger amplitude results from reduced inertia or damping ratio at a fixed Strouhal frequency, it adversely affects thrust generation.

The swimmer with an actively pitching tail generates higher thrust than its passive counterparts. In these cases, a pitching amplitude of

is required to ensure that the trailing edge of the tail spans the peak-to-peak amplitude of the carangiform swimmer (

). The heaving amplitude of the tail, defined as the displacement of the peduncle, is

, which is relatively smaller than the pitching amplitude of an actively pitching tail. When such a large angular amplitude (pitching) is combined with a small linear amplitude (heaving), the power expenditure increases significantly, particularly at higher Strouhal frequencies. The larger peak-to-peak amplitude corresponds to greater thrust production. In contrast, for the passively pitching tail, the maximum observed pitching angle does not exceed

. This reduced pitching angle explains the lower thrust coefficients observed. However, it also results in a lower-power swimming mode, as the pitching of the tail requires less input power. These two contrasting behaviors are captured quantitatively by the power ratio (

), shown in

Figure 11.

Figure 11a and

Figure 11b show the

as a function of

for Re = 500 and Re = 5000, respectively. The power ratio is plotted on a logarithmic scale to capture the full range of values and trends. The solid black line represents the power ratio for the actively pitching tail, which serves as a reference for comparison with the cases with a passively pitching tail. The region above this line, highlighted in blue, represents the configurations where the tail with passive pitching outperforms the active counterpart. At Re = 500, a significant number of cases with a passively pitching tail achieve higher

than those with the active tail. As

increases, the power ratio of the cases with a passive tail shows a modest upward trend, whereas the cases with the active tail only peaks at

and then decreases subsequently. Indicating that at lower Reynolds numbers, the passive tail often provides a performance advantage based on the

.

In contrast, at Re = 5000, most of the cases with a passively pitching tail exhibit lower power ratios than their active counterparts. Only a limited number of configurations outperform the active case, and these are again concentrated near . Thus, the overall trend shifts with Reynolds number: passively pitching tails show superior performance at Re = 500, while actively pitching tails dominate at Re = 5000. When passively pitching tail configurations are compared using thrust production and power ratio as performance metrics, a consistent trade-off emerges. Configurations that generate larger mean thrust tend to exhibit lower power ratios, whereas those with lower mean thrust generally achieve higher power ratios. An intermittent case at , with and , shows a unique transition from thrust-dominant to drag-dominant behavior and back to thrust-dominant behavior. This case reaches a maximum pitching angle of and is the only configuration among the 150 simulations to exhibit such dynamics. Given its rarity, this case is not examined further in the present study, primarily because no conclusive correlation or influence of any controlling parameter can be established.

From the quantitative analysis of the results, we observe a consistent trend for both the actively and passively pitching tails: as the Strouhal frequency increases, the thrust coefficient increases. To further investigate this phenomenon, we examine the vortex street in the wakes of the swimmers at Re = 500, and 5000. To keep the discussion centred on the role of Strouhal frequency, we consider all cases of the actively pitching tail for increasing

. For the passively pitching tail, we focus on configurations with fixed parameters

and

, varying only the Strouhal frequency. Both stable and unstable configurations with passively pitching tails are included to provide additional insight into the origin of the instabilities observed at a higher

seen earlier in the stability maps (

Figure 8).

We first examine the vortex dynamics of the swimmers at Re = 500, as shown in

Figure 12. The first column (

Figure 12a–e) presents the contours of vorticity for cases with an actively pitching tail, whereas the second column (

Figure 12f–j) corresponds to the cases with a passively pitching tail. For each case, we report the

, to quantify the propulsive performance associated with the observed wake structures. In

Figure 12,

denotes a single vortex shed into the wake during a half oscillation cycle.

From

Figure 12a,f, we observe that at

, the vortex street in the wake of both swimmers is faint. Nevertheless, even from these weak signatures, it is clear that both wakes form a classical von Kármán vortex street, typically associated with drag-dominated flows. For the actively pitching tail, although the mean thrust coefficient

is positive, its value is too small to generate an effective thrust. As the

increases to

and

(

Figure 12b,c,g,h), the wake transitions to a reverse von Kármán vortex street in all cases. This transition coincides with increasing values of

. With higher

, the strength of the coherent structures also intensifies. For the actively pitching tail at

and

, the wake remains reverse von Kármán, with the vortices becoming progressively stronger and persisting further downstream (

Figure 12d,e). It is consistent with the steady increase in

observed at higher Strouhal frequencies.

In contrast, at

and

, the passively pitching tail produces asymmetric wakes (

Figure 12i,j). These asymmetric reverse von Kármán vortex streets are generally associated with stronger thrust-producing wakes. Godoy-Diana et al. [

34] highlighted that such symmetry breaking occurred at high Strouhal frequencies. This asymmetry implies that the net force generated by the flapping tail is no longer aligned with the mid-plane of the swimmer.

Similarly, we now examine the vortex dynamics of both swimmers at Re = 5000, as shown in

Figure 13. The overall layout of this figure is identical to that of

Figure 12. For the case with a passively pitching tail at

, the results exhibit instabilities, as highlighted by the red periphery in

Figure 13h–j. In

Figure 13,

corresponds to a single vortex pair shed during a half oscillation cycle (one clockwise rotating vortex paired with a counter-clockwise rotating vortex).

Figure 13a and

Figure 13f show the wake topology of the actively and passively pitching tail configurations, respectively, at

. For the case with an active tail, the wake resembles that observed at Re = 500, whereas the passive tail exhibits a

–

shedding pattern. As the

increases to

, the actively pitching tail maintains the same topology, while the passive tail develops a reverse von Kármán vortex street characterized by a

wake pattern. Although the wake corresponds to a reverse von Kármán street, minor instabilities begin to appear, as shown in

Figure 13g. For the actively pitching tail, an increasing Strouhal frequency continues to increase thrust, consistent with the trend observed at Re = 500. However, from

–

, the wake becomes increasingly asymmetric, with the asymmetry becoming more pronounced at a higher

(

Figure 13c–e). On the other hand, for the passive tail, the red-outlined region (

Figure 13h–j) highlights the growing instabilities in the wake as the Strouhal frequency increases.

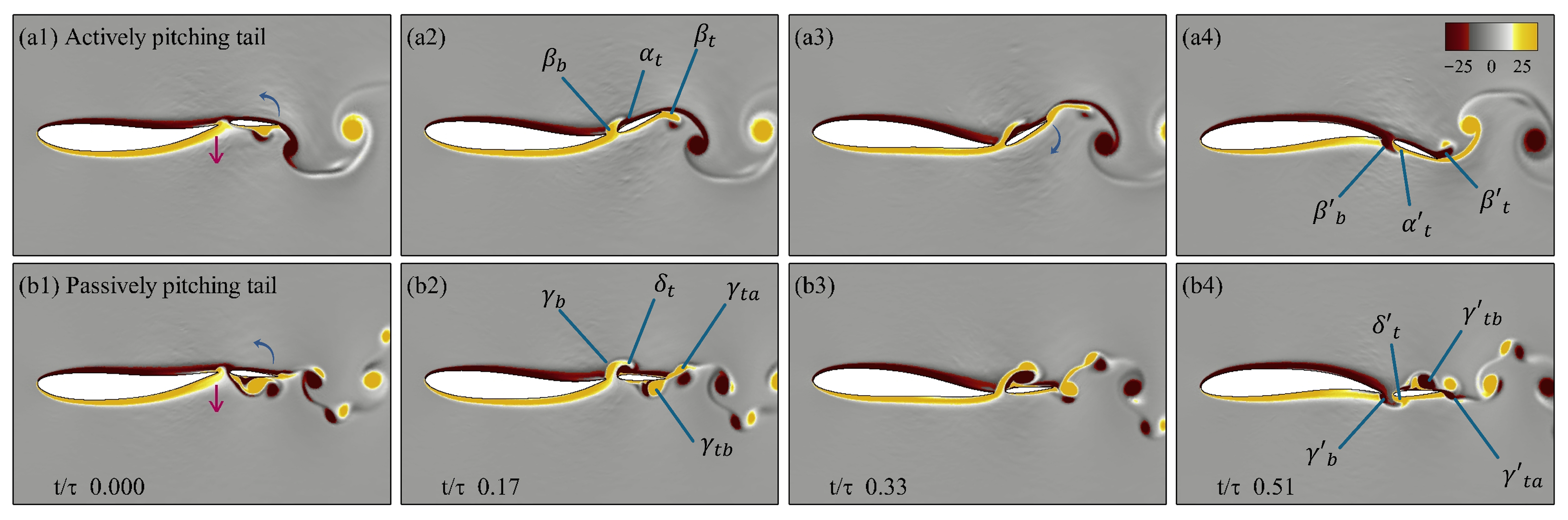

From the earlier analysis of the power ratio at

and Re = 500, the passively pitching tail (

) produce more than twice the power ratio of than an actively pitching tail at the same

. To better understand the effect of the flow on the tail, we examine the vortex dynamics of both configurations, shown side by side in

Figure 14.

Figure 14a and

Figure 14b present the drag (

), lift (

), and moment (

) coefficients over one oscillation cycle for the cases with an actively pitching tail and a passively pitching tail, respectively. The corresponding

z-vorticity fields are displayed in

Figure 14c,d at four time instants, capturing the motion as the body undulates from its uppermost position, descending to the lowest point, and ascending back to complete the full cycle. In both cases, the undulation of the body and the heaving of the tail remain in phase.

In

Figure 14c, panel c1 shows the tail at the start of its downward heaving stroke. In panel c2, a leading-edge vortex (

) forms on the upper surface of the tail, producing positive lift and negative drag (i.e., positive thrust). Simultaneously, the tail pitches downward, generating a trailing-edge vortex (

), while the body’s undulation produces another vortex at the trailing edge of the body (

). Due to the effect of

, leading to an early formation of

which results in the reduction of the pressure on the upper surface. This increase in the pressure differential results in an increase in the thrust observed in

Figure 14a, similar to the observation drawn by Akhtar et al. [

35]. As the tail completes its downward stroke (panel c3), it begins to pitch upward and

starts to detach from the trailing edge. During the subsequent upward stroke (panel c4),

constructively interacts with the newly formed trailing-edge vortex (

), while a new leading-edge vortex develops on the lower surface, resulting in negative lift and negative drag (positive thrust) due to the decrease in the pressure on the lower surface.

Figure 14(d1–d4), shows the four instances of the passively pitching tail from panel d1 to d4, respectively. As the tail initiates its downstroke, the lift coefficient decreases (creating downward force), which is in the same direction as the heaving displacement, contributing to less power expenditure by the tail. The moment coefficient increases as the tail heaves downward, which leads to the counterclockwise pitching of the tail about its peduncle. As the tail moves downward, there is a formation of a larger vortex at the leading edge of the tail (

) and the trailing edge of the body (

). The previously shed vortex from the leading edge of the tail constructively interferes with the trailing edge vortex (

) as seen in panel d2, increasing the strength of this trailing edge vortex. As seen from panel d3, due to the smaller angle of attack of the tail,

does not stay attached to the boundary layer, which leads to the separation of

resulting in the formation of a dipole with

, which is considered detrimental to the production of thrust. When this scenario is compared to the one observed in the actively pitching tail, the formation of the leading edge vortex in both cases leads to an increase in thrust, but with an actively pitching tail, due to the higher angle of attack, the vortex stays attached to the boundary and produces relatively higher thrust. In the same frame, the formation of the trailing edge vortex (

) begins as the tail initiates its upward stroke. In panel d4, the dipole which is formed from

and

breaks as

constructively merges into

which leads to an increase in thrust.

Based on the earlier analysis, at a Reynolds number of Re = 500,

of the passively pitching tail configurations outperformed their actively pitching counterparts in terms of power ratio. In contrast, at a higher Reynolds number of Re

, only

of the passively pitching tail configurations demonstrated better performance, with most of these cases clustered around a Strouhal frequency of

. Notably, the passive tail configuration with parameters

and

achieved nearly

times better performance than that of the corresponding active case at the same Strouhal frequency. A comparative analysis of the vortex dynamics over a half oscillation cycle for both cases is presented in

Figure 15, shown in comparison.

Figure 15a–d illustrate four key time instances of an actively pitching tail during its downward stroke, corresponding to panels a

1–a

4, respectively. In panel a1, as the tail initiates its downward stroke, a trailing-edge vortex (

) begins to form due to the body’s undulation. As the tail continues to move downstroke, a leading-edge vortex (

) develops on the upper surface of the tail. Simultaneously, as the tail pitches downward about the peduncle, a trailing-edge vortex (

) is formed. A key observation between the actively pitching tail at Re = 500 (

Figure 14c) and Re = 5000 (

Figure 15a) is that while

remains attached to the boundary layer in both cases, at the lower Reynolds number, the vortex structure appears more coherent. Contrarily, at Re

, the leading-edge vortex is more tightly bound to the boundary layer, contributing to improved thrust generation. In panel a3, as the tail approaches the end of its downward stroke, the interaction of

with

produces a jet-like effect, similar to the mechanism described by Gao et al. [

23]. At this instance, the trailing-edge vortex continues to strengthen as the tail’s angle of attack reaches its peak. Panel a4 captures the moment just after the downward stroke ends. Here, the upward pitching of the tail causes the detachment of the trailing-edge vortex

, while a new vortex

is formed on the upper surface. The constructive interaction between

and

leads to the production of thrust. At this same instant, a new leading-edge vortex (

) from the tail and a trailing-edge vortex (

) from the body appear on the lower surface.

Similarly,

Figure 15b illustrates the passively pitching tail over a half oscillation cycle as it completes its downward stroke. The four snapshots of this motion are shown in panels b1–b4. In panel b1, as the tail begins its downstroke, a trailing-edge vortex (

) is generated from the undulating body from the lower surface. A core difference between the cases with an actively pitching tail and those with a passively pitching tail lies in the angle of attack. For the passive tail, the angle of attack does not exceed

, which is significantly smaller than

observed in the active tail. This reduced angle of attack is consistent across all configurations with the passively pitching tail. However, due to the smaller angle of attack, the leading-edge vortex (

) detaches prematurely from the boundary layer of the tail. As it remains close to the surface,

subsequently reattaches to the boundary layer, as seen in panel b3. Upon reaching the trailing edge of the tail, it sheds as a coherent, clockwise-rotating vortex from the upper surface, relabeled as

. Such reattachment and delayed shedding help maintain a favorable pressure distribution along the surface of the tail and promote the formation of a reverse jet downstream, thereby contributing to the generation of thrust as seen in panel b4. In the same panel, we also observe the formation of a new leading-edge vortex (

) on the tail and a trailing-edge vortex (

) from the undulating body on the lower surface.

The primary contributor to the higher thrust observed in all actively pitching tail configurations is the large angle of attack and a consistent lag between the heaving and the pitching displacement of the tail, which ensures that the leading-edge vortex formed on the tail remains attached to the boundary layer, thereby sustaining thrust generation. A secondary contributor is the constructive interaction between the leading-edge vortex in the first half of the oscillation cycle and the trailing-edge vortex formed in the second half, which further enhances thrust production. However, this higher thrust comes at the cost of a reduced power ratio. Contrarily, for the passively pitching tail, the smaller angle of attack causes the leading-edge vortex to detach prematurely from the boundary layer of the tail, which is detrimental to the production of the thrust. Nevertheless, when performance is evaluated in terms of power ratio, the passively pitching tail outperforms its active counterpart at Re = 500. At Re = 5000, however, the trend reverses: the actively pitching tail exhibits better performance, particularly at higher Strouhal frequencies, due to the instabilities and inconsistencies observed in the case with a passively pitching tail as discussed earlier.

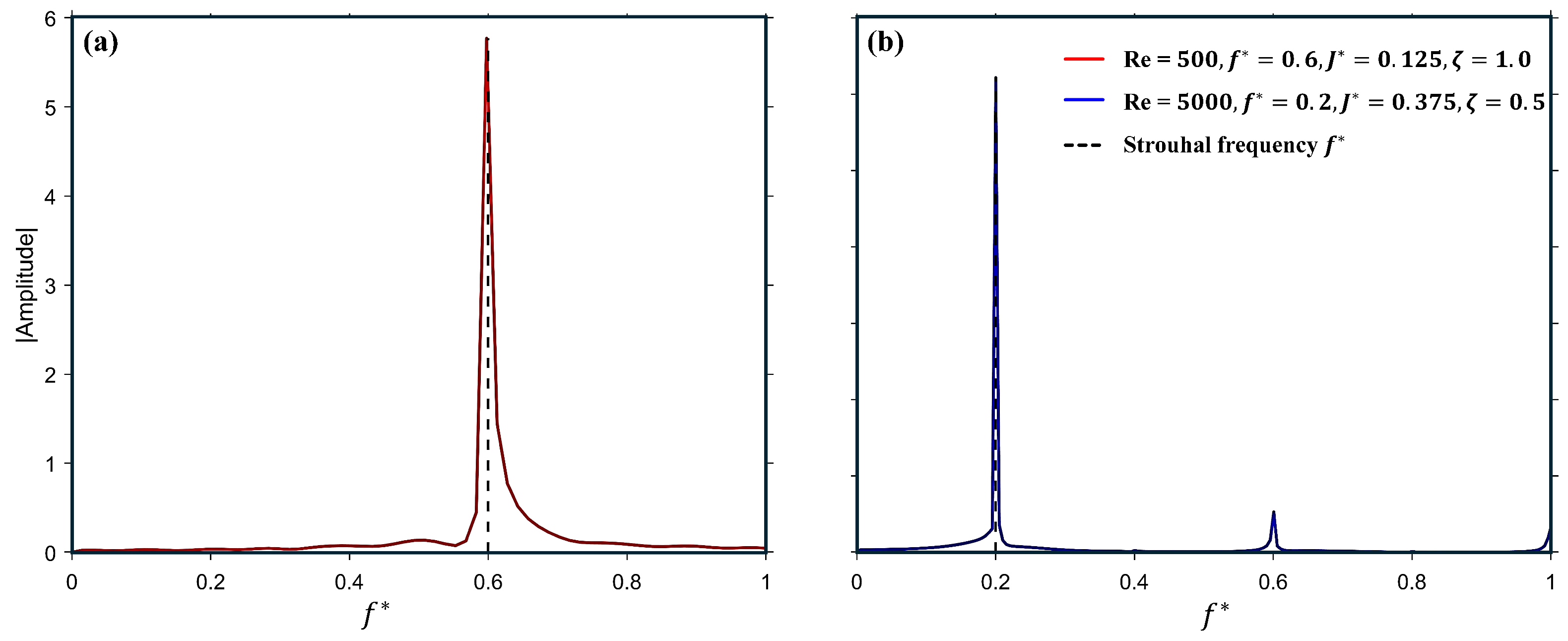

The configurations with passively pitching tails provide valuable insight for a detailed analysis. Although the pitching amplitude in these cases is comparatively smaller than that of the actively pitching tails, the pitching frequency remains near resonance, as indicated by the spectral compositions of the pitching response of the tail in

Figure 16a,b. The normalized fundamental frequency aligns well with the heaving frequency of the corresponding case, as highlighted by the dashed line.