The Third Skin: A Biomimetic Hydronic Conditioning System, a New Direction in Ecologically Sustainable Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology: Biometric Analysis

2.1. Bio-Inspired Ecological Sustainable Design Innovation

- Optimize site potential.

- Minimize non-renewable energy consumption and waste.

- Use environmentally preferable products.

- Protect and conserve water.

- Improve indoor air quality.

- Enhance operational and maintenance practices.

- Create healthy and productive environments.

2.2. Role of Biomimicry in System Design

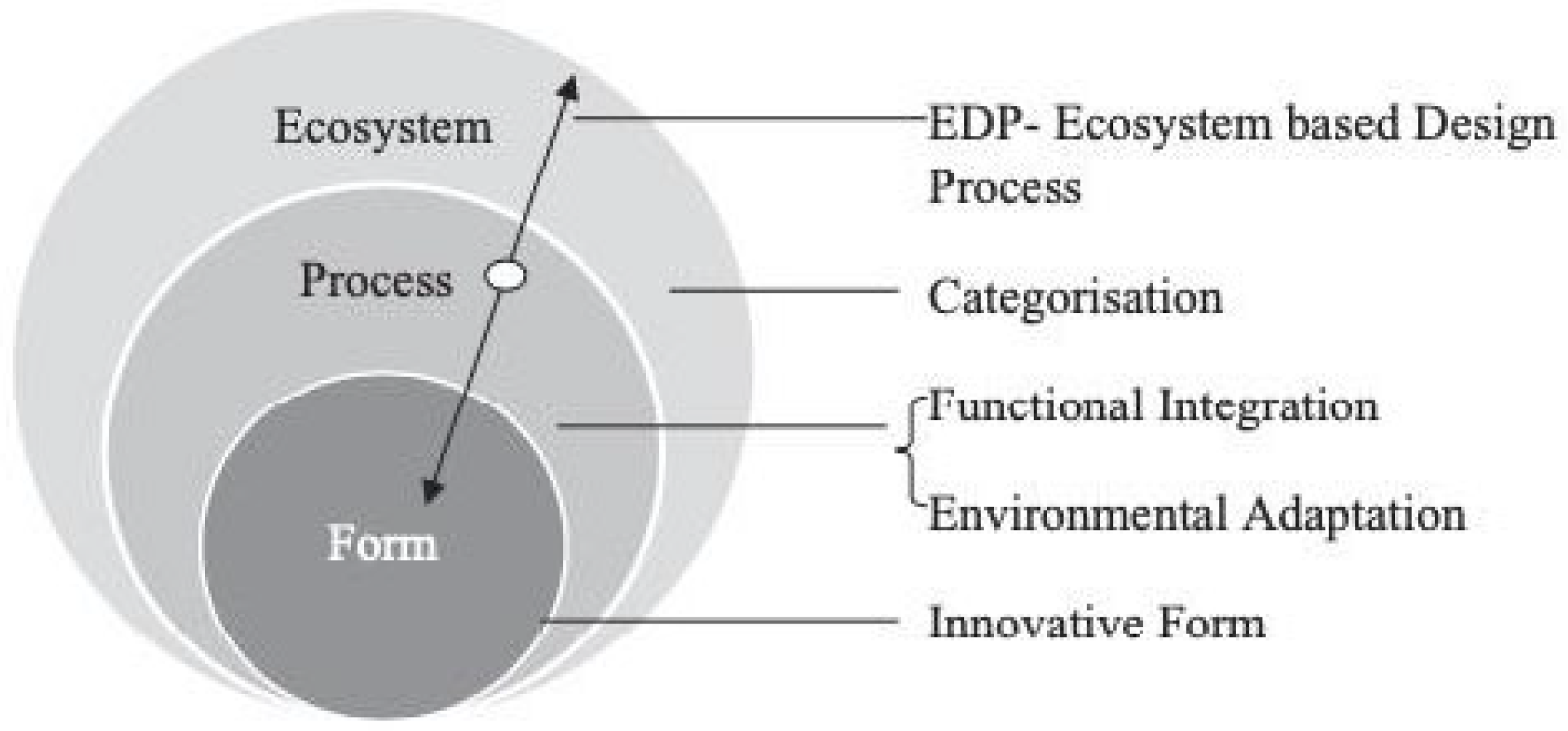

2.3. An Explanation of the Biometric Analysis

- Scales of application: How is the biomimetic-inspired hydronic conditioning system integrated with architectural facade systems in buildings?

- Ecosystem: How does the integrated system fit with its environmental context?

- Process: How does the integrated system perform?

- Form: What are the physical characteristics of the systems?

- Biomimicry design approaches: Direct sources from natural systems (Bio-inspiration) and Indirect sources from natural systems (Third skin).

2.4. Steps for Conducting Biometric Biomimetic Analysis for Hydronic Systems

- The scale of application: process, form, ecosystem levels of the functioning of the human body, and its analogical transfer to the hydronic system.

- Design process: categorization, functional integration, environmental adaptation, and expression of the form of both systems.

- Biomimicry approach: direct (mimicking the circulatory system of the human body) and indirect approach (design strategies, lessons, and principles taken from the third skin strategy).

2.5. Implementing Biomimicry in Radiant Conditioning System Design

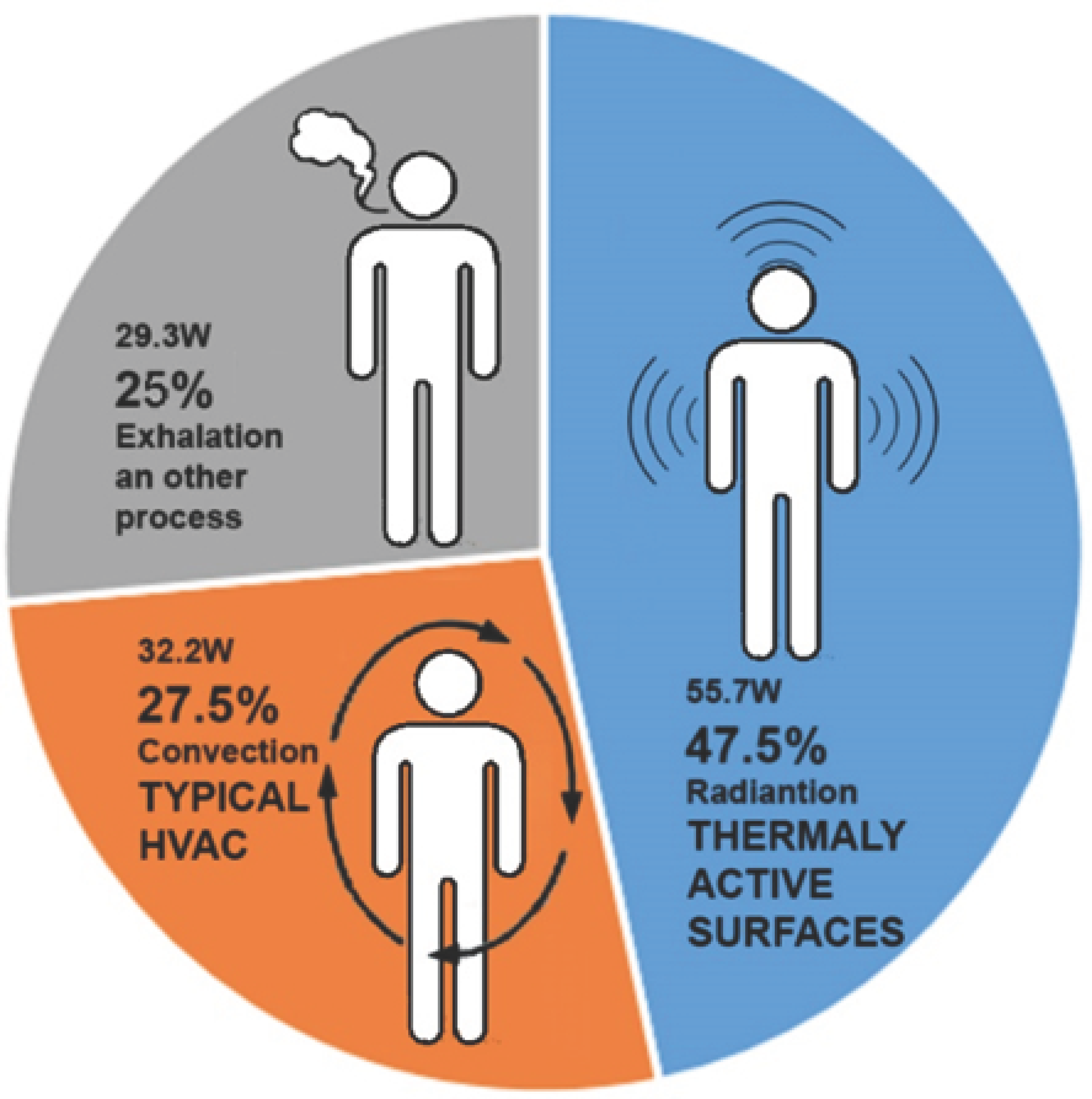

3. Direct Inspiration from Human Thermal Comfort and Heat Transfer

3.1. Heat Transfer and Thermal Comfort

3.2. Adaptive Thermal Comfort Model

4. Direct Inspiration from the Human Circulatory System

4.1. Human Circulatory System Components and Key Processes

- Heart: The heart is a muscular organ that pumps blood throughout the body, divided into four chambers: the left and right atria, and the left and right ventricles.

- Arteries: Arteries are blood vessels that carry oxygenated blood away from the heart to the rest of the body. They are thick-walled and muscular to withstand high blood pressure.

- Veins: Veins are blood vessels that carry deoxygenated blood back to the heart. They have thinner walls than arteries and are less muscular.

- Capillaries: Capillaries are tiny blood vessels that allow for the exchange of oxygen and nutrients with tissues and organs.

- Blood: Blood is a liquid tissue that carries oxygen, nutrients, hormones, and waste products throughout the body.

- Systole: The heart contracts to pump blood out of its chambers.

- Diastole: The heart relaxes between beats, allowing blood to flow back into its chambers.

- Pumping Action: The heart pumps about 2000 gallons of blood every day.

- Blood Pressure Regulation: Blood pressure is regulated by adjusting blood vessel diameter, which affects blood flow. This aspect is similar in a hydronic system, where tubing diameter changes flow rate and pressure.

4.2. Blood Vessels and the Piping in Radiant Systems

4.3. Heart vs. Hydronic Control and Distribution System

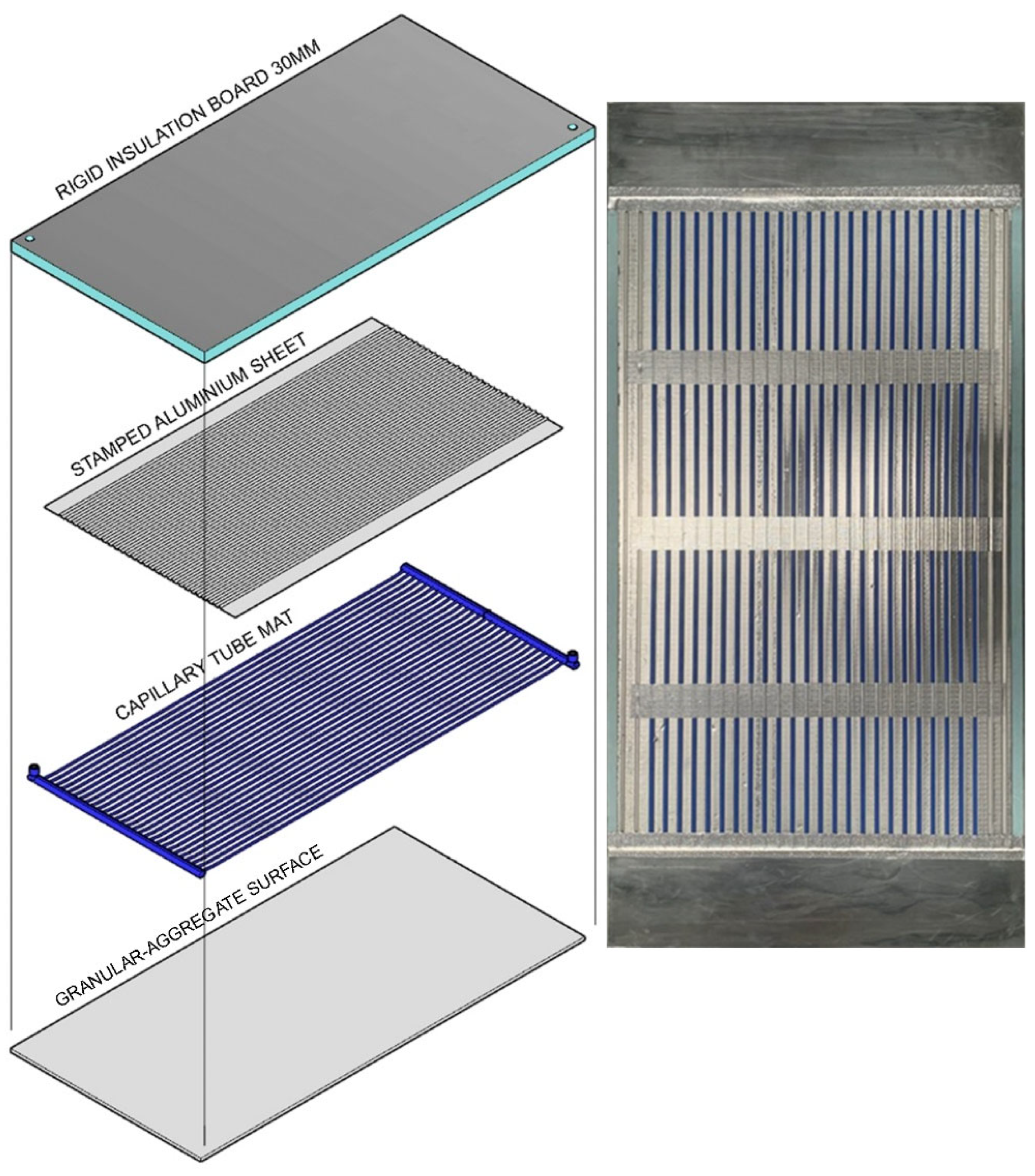

4.4. Capillary Tube Mat and Capillary Blood Vessels

4.5. Hydronic Radiant System Function—Lessons Learn from the Human Circulatory System

- Blood Flow: Blood flows through the circulatory system in one direction, from the heart to the rest of the body and back to the heart.

- Deoxygenated Blood Return: Deoxygenated blood returns to the heart through the superior and inferior vena cava (large veins).

- Oxygenation: The heart pumps deoxygenated blood into the lungs, where it picks up oxygen from inhaled air.

- Oxygen-rich Blood: The oxygen-rich blood returns to the heart through the pulmonary veins and is pumped into the aorta (the largest artery).

- Distribution: Various parts of the body, through smaller arteries, capillaries, and veins, distribute oxygen-rich blood.

- Waste Removal: Deoxygenated blood carries waste products back to the heart, where they are removed from the body through exhalation (breathing out).

- Oxygen Delivery: The circulatory system delivers oxygen to cells, enabling energy production.

- Waste Removal: It removes waste products from cells, preventing their accumulation and toxicity.

- Temperature Regulation: It helps regulate body temperature by circulating warm or cool blood as needed.

- Hormone Transport: It transports hormones produced by endocrine glands to target cells.

5. Indirect Inspiration—The Third Skin

6. The Infrastructure for the Bioinspired Hydronic System

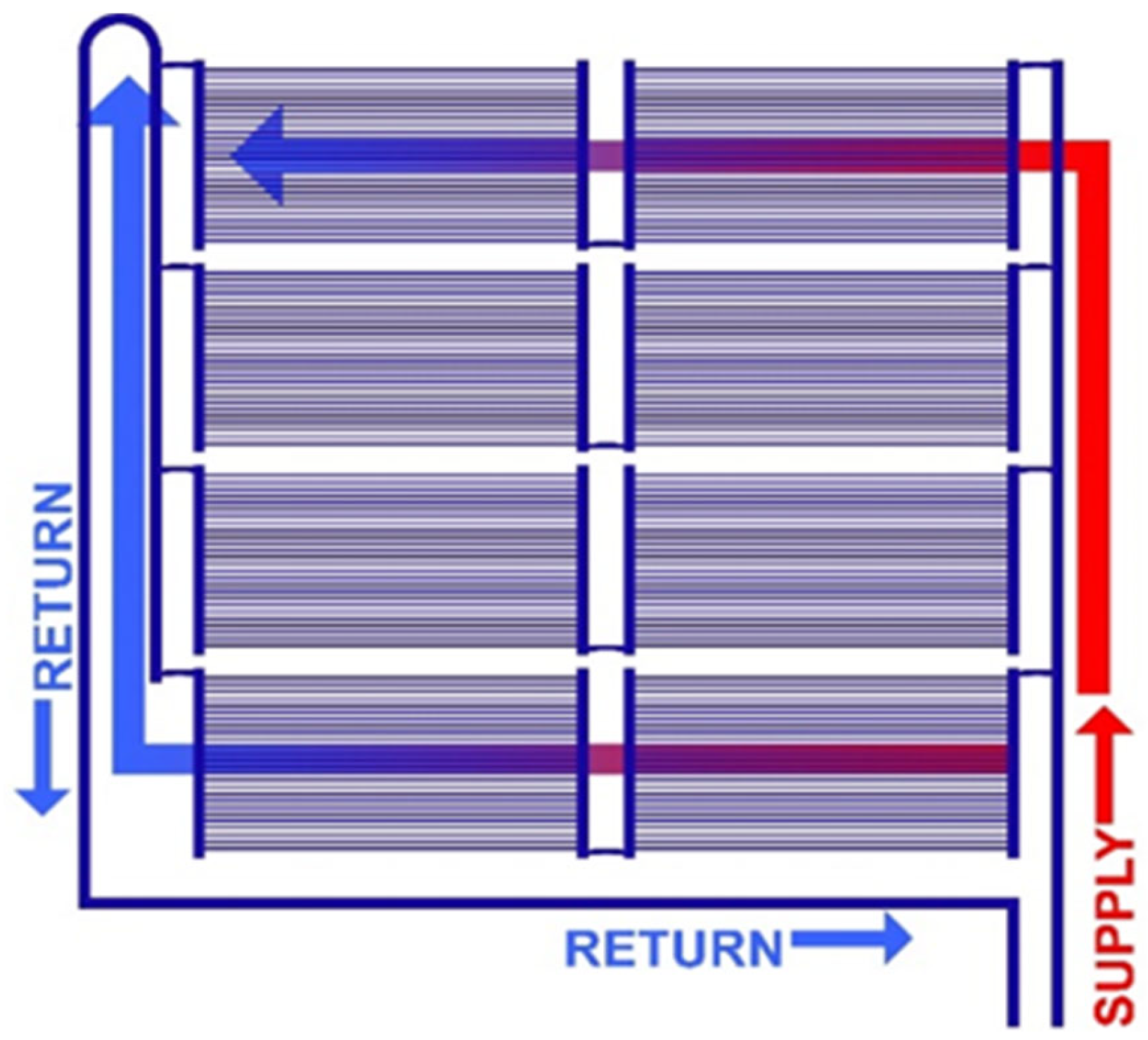

6.1. Capillary Flow Systems

- Parallel venation: Veins run parallel to each other, often found in monocots like grasses.

- Reticulate (or pinnate) venation: Veins form a network or branching pattern, typical in dicots like broad-leaved plants.

- Palmate venation: Several main veins radiate from a central point, also common in dicots.

6.2. Serpentine Tubing vs. Capillary Tube Mats

6.3. Application of These Mechanisms in Hydronic Conditioning Systems

6.4. Performance Evaluation Comparison

7. Results and Discussion

7.1. Results

7.1.1. Theoretical Framework

7.1.2. Validation

7.2. Discussion

- Filtering: Just as human skin regulates the variations between the internal and external environment, hydronic systems filter and adapt to heating and cooling demands effectively.

- Layered Functions: The multiple layers of human skin performing diverse functions suggest that architectural skins should similarly possess the capability to multitask, thereby enhancing environmental performance.

- Permeability: The properties of human skin, which facilitate the exchange of nutrients and gases, can inform the design of hydronic systems. Ensuring sufficient surface area for thermal exchange will contribute to more efficient and responsive systems.

- Connectivity: The interconnectedness observed in skin underscores the importance of integrating with the surrounding environment. While hydronic systems aim for efficient energy transfer, fostering meaningful connections with their context is also essential [48].

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rhee, K.-N.; Kim, K.W. A 50 year review of basic and applied research in radiant heating and cooling systems for the built environment. Build. Environ. 2015, 91, 166–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, K.-N.; Olesen, B.W.; Kim, K.W. Ten questions about radiant heating and cooling systems. Build. Environ. 2017, 112, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, R.; Olesen, B.W.; Kim, K.W. Part 2: History of radiant heating & cooling systems. Ashrae J. 2010, 52, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Do, H.Q.; Luther, M.B.; Matthews, J.; Martek, I.; Horan, P. An experimental evaluation of the thermal performance of lightweight radiant ceiling panel designs. Energy Build. 2025, 344, 115966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Rismanchi, B.; Brey, S.; Aye, L. Thermal and energy performance evaluation of a full-scale test cabin equipped with PCM embedded radiant chilled ceiling. Build. Environ. 2023, 237, 110348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, X.-H.; Jiang, Y. Experimental evaluation of a suspended metal ceiling radiant panel with inclined fins. Energy Build. 2013, 62, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, G.; Shen, C.; Han, Z.; Liao, W.; Chen, D. Experimental investigation on the cooling performance of a novel grooved radiant panel filled with heat transfer liquid. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, R. Radiant cooling. Archit. Sci. Rev. 1963, 6, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Wu, H.; Liu, J.; Ding, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, G.; Xu, X. A comprehensive review of high-transmittance low-conductivity material-assisted radiant cooling air conditioning: Materials, mechanisms, and application perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 113972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Ma, W.; Yao, S.; Xu, X.; Niu, J. Enhancing the cooling capacity of radiant ceiling panels by latent heat transfer of superhydrophobic surfaces. Energy Build. 2022, 263, 112036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ding, Y.; Feng, Y. A novel research for restraining the condensation of radiant air conditioner by superhydrophobic surface. Energy Build. 2023, 296, 113398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Gong, M.; Sun, J.; Lin, Y.; Tu, K.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, T.; Li, X.; Tan, X. The design and performance research of PTFE/PVDF/PDMS superhydrophobic radiative cooling composite coating with high infrared emissivity. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 108406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouacida, T.; Bentoumi, L.; Bessaïh, R. Experimental study of a low-cost ceiling cooling system in the north Algerian climate. Energy Build. 2023, 293, 113196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.Q.; Matthews, J.; Luther, M.B.; Martek, I.; Horan, P. Development and thermal performance testing of radiant conditioning ceiling panels. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2024, 68, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canbazoğlu Bilici, S.; Küpeli, M.A.; Guzey, S.S. Inspired by nature: An engineering design-based biomimicry activity. Sci. Act. 2021, 58, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appio, F.P.; Achiche, S.; Martini, A.; Beaudry, C. On designers’ use of biomimicry tools during the new product development process: An empirical investigation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 29, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X. Climate change adaptation pathways for Australian residential buildings. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 2398–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Cooper, P.; Daly, D.; Ledo, L. Existing building retrofits: Methodology and state-of-the-art. Energy Build. 2012, 55, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.M.; Hu, N.; Østergaard, D.S.; Svendsen, S. A novel concept for energy-efficient floor heating systems with minimal hot water return temperatures. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2069, 012106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSA. Sustainable Design. 2025, USA General Services Administration. Available online: https://www.gsa.gov/real-estate/design-and-construction/sustainability/sustainable-design (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Zari, M.P. Biomimetic design for climate change adaptation and mitigation. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2010, 53, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, A.; Hyde, R. A model based on Biomimicry to enhance ecologically sustainable design. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2012, 55, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, K. Thermally Active Surfaces in Architecture; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- EES. Radiative vs. Convective Conditioning. 2025, Environmental Energy Services. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LXunNLNAOjs (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Janda, K.B. Buildings don’t use energy: People do. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2011, 54, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, T.; Soh, Y.C.; Bose, S.; Xie, L.; Li, H. On assuming Mean Radiant Temperature equal to air temperature during PMV-based thermal comfort study in air-conditioned buildings. In Proceedings of the IECON 2016-42nd Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Florence, Italy, 23–26 October 2016; pp. 7065–7070. [Google Scholar]

- ASHRAE Standard 55-2017; Thermal Environment Conditions for Human Occupancy. American Society of Heating. Refrigerating and Air Conditioning Engineers Inc.: Atlanta, Georgia, 2017.

- Luther, M.; Tokede, O.; Liu, C. Applying a comfort model to building performance analysis. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2020, 63, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dear, R.; Brager, G.S. The adaptive model of thermal comfort and energy conservation in the built environment. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2001, 45, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, B.; Sumam, K. Blood flow in human arterial system-a review. Procedia Technol. 2016, 24, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cracowski, J.L.; Roustit, M. Human skin microcirculation. Compr. Physiol. 2020, 10, 1105–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, J.; Olesen, B.W.; Petras, D. Low Temperature Heating and High Temperature Cooling: REHVA GUIDEBOOK No 7; Federation of European Heating and Air-Conditioning Associations: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- López-Manjón, A.; Angón, Y.P. Representations of the human circulatory system. J. Biol. Educ. 2009, 43, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tye-Gingras, M.; Gosselin, L. Comfort and energy consumption of hydronic heating radiant ceilings and walls based on CFD analysis. Build. Environ. 2012, 54, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvik, R.K. The total artificial heart. Sci. Am. 1981, 244, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinoda, J.; Kazanci, O.B.; Tanabe, S.-i.; Olesen, B.W. A review of the surface heat transfer coefficients of radiant heating and cooling systems. Build. Environ. 2019, 159, 106156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causone, F.; Corgnati, S.P.; Filippi, M.; Olesen, B.W. Experimental evaluation of heat transfer coefficients between radiant ceiling and room. Energy Build. 2009, 41, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantelic, J.; Schiavon, S.; Ning, B.; Burdakis, E.; Raftery, P.; Bauman, F. Full scale laboratory experiment on the cooling capacity of a radiant floor system. Energy Build. 2018, 170, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, F.; Raftery, P.; Schiavon, S.; Karmann, C.; Pantelic, J.; Duarte, C.; Woolley, J.; Dawe, M.; Graham, L.T.; Miller, D. Optimizing Radiant Systems for Energy Efficiency and Comfort. In Energy Research and Development Division Final Project Report; California Energy Commission: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Quarteroni, A. Modeling the Heart and the Circulatory System; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 7730 2005-11-15; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment: Analytical Determination and Interpretation of Thermal Comfort Using Calculation of the PMV and PPD Indices and Local Thermal Comfort Criteria. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- Sack, L.; Dietrich, E.M.; Streeter, C.M.; Sánchez-Gómez, D.; Holbrook, N.M. Leaf palmate venation and vascular redundancy confer tolerance of hydraulic disruption. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1567–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosa, M.; Labat, M.; Lorente, S. Constructal design of flow channels for radiant cooling panels. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 145, 106052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanowicz, Ł.; Wojtkowiak, J. Thermal performance of multi-pipe earth-to-air heat exchangers considering the non-uniform distribution of air between parallel pipes. Geothermics 2020, 88, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.Q.; Luther, M.B.; Matthews, J.; Martek, I. Experimental evaluation of radiant ceiling panels in office building perimeter zones. Energy Build. 2025, 349, 116531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Dear, R.J.; Akimoto, T.; Arens, E.A.; Brager, G.; Candido, C.; Cheong, K.; Li, B.; Nishihara, N.; Sekhar, S.; Tanabe, S. Progress in thermal comfort research over the last twenty years. Indoor Air 2013, 23, 442–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, R. Site-Specific Bioinspired Architecture—A Case Study of the Allen–Lambe House by Frank Lloyd Wright: The Pragmatic versus the Naturalistic, Intent versus Realization. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzholzer, S. Conceptualizing urban places as a “Fourth Skin”. In Proceedings of the PLEA 2006—23rd International Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Conference Proceedings, Geneva, Switzerland, 6–8 September 2006; pp. 465–471. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, S.C.; Zhong, X.L.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, T.W.; Chan, K.C.; Lee, K.Y.; Chao, C.Y. Bio-inspired cooling technologies and their applications in buildings. Energy Build. 2020, 225, 110313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale of Application | Design Process | Direct Approach: Specific Mimicking | Indirect Approach: General Mimicking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecosystem: How does it fit with the whole? → | Categorization: What is the type of classification? ↓ | Type of species, physical characteristics, climatic zones, ↔ Relationship between species, size, and form variations | Identification of building type, types of users, size variations, form variations, relationship with users and organisms, and climatic zones |

| ↓↑ Process: → How does it perform, and how is it made? ↓↑ → | Functional integration –What are the innovative strategies? ↓ | Hierarchy of functions: primary, secondary, techniques, physical characteristics, ↔ Mechanisms, Patterns, behavioural patterns, needs, communication, organization | Users and user needs, hierarchy of functions: primary, secondary functions, techniques, physical characteristics, mechanisms, user behaviour, patterns, needs, occupancy, communication |

| Environmental Adaptation –what are the innovative strategies? ↓ | Macro and micro ↔ environment, physical characteristics, habitat, topography, macro and micro climate: wind, sun path, temperature, humidity, rainfall | Macro and micro-environment, physical characteristics, habitat topography, macro and microclimate: wind, sun path, temperature, humidity, rainfall | |

| Form: → What is the shape? | Innovation of form—what is the expression? | Design fundamentals: lines, shape, texture, colour, patterns, geometric progression: module, unit to whole, scale, and proportions | Design fundamentals: lines, shape, texture, colour, patterns, geometric progression: module, unit to whole, scale, and proportions |

| Analogical Translations | Nature Studies Analysis | Typological Analysis | Design Spiral | Bio-TRIZ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomimicry scales of application, | Form, process, ecosystem, | Organism behaviour, ecosystem, | Form, process, ecosystem System, sub-system, | System, sub-system, |

| Ecosystem: How does it fit with the whole? Process: How does it perform, and how is it made? | Categorization—scientific reasoning, functional adaptation, contextual adaptation, aesthetic reasoning | Form, process, material, construction, function | Identify, interpret, discover, abstract, emulate, evaluate | Problem, problem understanding, logical solutions |

| Form: What is the shape? | Natural systems to built systems and built systems to Natural systems? | Biology influencing design and design looking to biology | Biology investigating design and design investigating biology | Solution-driven approach and problem-driven approach |

| Areas | Instrument/Sensor | Measurement/Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Weather station | Wind speed anemometer Global solar irradiance sensor Relative Humidity sensor Dry-bulb temperature sensor | External wind speed (m/s) External solar radiation (W/m2) External humidity (%) External air temperature (°C) |

| Window | Solar Irradiance sensors | Solar radiation received at the window (W/m2) Solar radiation transmitted through the window into the chamber (W/m2) |

| Thermal comfort cart | CO2 sensor Relative humidity sensor Globe thermometers Anemometers Thermistors | CO2 level (ppm) Relative Humidity (°C) Mean radiant temperature calculation (°C) Air velocity (m/s) Air temperature (°C) |

| Chamber, floor, and ceiling | Thermocouple Heat flux sensor Stratification thermocouples Thermal imaging camera | Radiant surface temperature (°C) Energy emission/energy transfer (W/m2) Air temperature stratification (°C) Chamber surface temperature (°C) |

| Human Body—Natural System | Capillary Hydronic System | |

|---|---|---|

| Circulatory system | Heart, Arteries, Veins, and Capillaries, Pressure regulation, expansion, and contraction. | Pump with regulated mixing temperature, Pressure vessel maintaining 1.0–2.0 bar, Manifolds, Main Piping, and Capillary tubing. |

| Surface Temperature | Regulated Skin Temperature via the circulatory system | A very shallow (minimal depth) of less than 5 mm is the “regulated skin” of the insulated panel. It is controlled via the changing (mixed) water supply temperature. |

| Heat transfer regulation | A self-regulated system in tune with its environmental temperature. The body releases, or gains heat from, surfaces and air temperatures. | Self-regulation of the energy transfer depends on temperature differences between the radiant surfaces and the room’s operative temperature. |

| Thermal comfort | Adaptive Model of Comfort implies that humans dress and acclimate according to the external environment. | A control system based on the Adaptive Model of Comfort using room operative temperature and external mean outdoor air temperature. |

| Sweating and condensation, | Skin sweating and evaporation as a cooling mechanism | Condensation concern has led to the development of a ‘dew point extension’ substrate material. A granular rough-edged surface that prevents water droplets from forming, creating a vapor film. |

| Air movement Dynamic response | Cooling in response to air movement at the skin. Evaporation of sweat. A fast responding system to changing thermal environments. | Air movement via the system integration with a ceiling fan at low velocity increases cooling capacity by 22% (can be higher). A dynamic response to thermal changes is combined through light-weight radiant panels (<10 min time constant), sensors, and an adaptive control system. |

| Item of Interest | Equipment Implemented | Description: Instrumentation/Control |

|---|---|---|

| Circulatory System | Pump, Mixing Valve, Flow Sensor, 6-way switching valve, Pressure Vessel | Variable Speed Pump: manual control 0–10 V control of valve opening/closing Mixing Return/Supply water Flow Rate: L/minute Temperature Sensor Pressure Guage |

| Panel ‘Skin’ Radiative Temperature | Temperature Sensor | Thermocouple/thermistor |

| Panel ‘Skin’ Energy Transfer | HFM Sensor | Heat Flux Meter (W/m2) |

| System Heat Transfer Regulation | Sensors with Control Program | System Supplied Water (thermistor) DB Room Air Temperature (thermistor) Panel Surface Temperature (thermistor) Heat Flux Meter (W/m2) |

| Adaptive Comfort Control | Sensors with Control Program | Average External (Outside) Air (thermistor) Indoor Operative Temperature: calculated (MRT & DB) PLC—Controller Hardware |

| Room Air Velocity Control | Variable Speed Ceiling Fan & Air Velocity Sensor | Variable Speed Fan—measured speeds with 6 room air velocity meters to obtain average air movement in the room |

| Thermal Comfort | Thermal Comfort Cart with Sensors and Data Logger | An ISO 7730 2005-11-15 [41] Comfort Index as calculated by the measured parameters of Air DB, Relative Humidity, Globe Temperature (MRT), Air Velocity, Clothing Index, and Metabolic Rate |

| Panel Response Time | Temperature Sensors and Data Logger | Water Supply Temperature Panel Surface Temperature Heat Flux Meter |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luther, M.B.; Hyde, R.; Gamage, A.; Do, H.Q. The Third Skin: A Biomimetic Hydronic Conditioning System, a New Direction in Ecologically Sustainable Design. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 843. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120843

Luther MB, Hyde R, Gamage A, Do HQ. The Third Skin: A Biomimetic Hydronic Conditioning System, a New Direction in Ecologically Sustainable Design. Biomimetics. 2025; 10(12):843. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120843

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuther, Mark B., Richard Hyde, Arosha Gamage, and Hung Q. Do. 2025. "The Third Skin: A Biomimetic Hydronic Conditioning System, a New Direction in Ecologically Sustainable Design" Biomimetics 10, no. 12: 843. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120843

APA StyleLuther, M. B., Hyde, R., Gamage, A., & Do, H. Q. (2025). The Third Skin: A Biomimetic Hydronic Conditioning System, a New Direction in Ecologically Sustainable Design. Biomimetics, 10(12), 843. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120843