DNS and Experimental Assessment of Shark-Denticle-Inspired Anisotropic Porous Substrates for Drag Reduction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

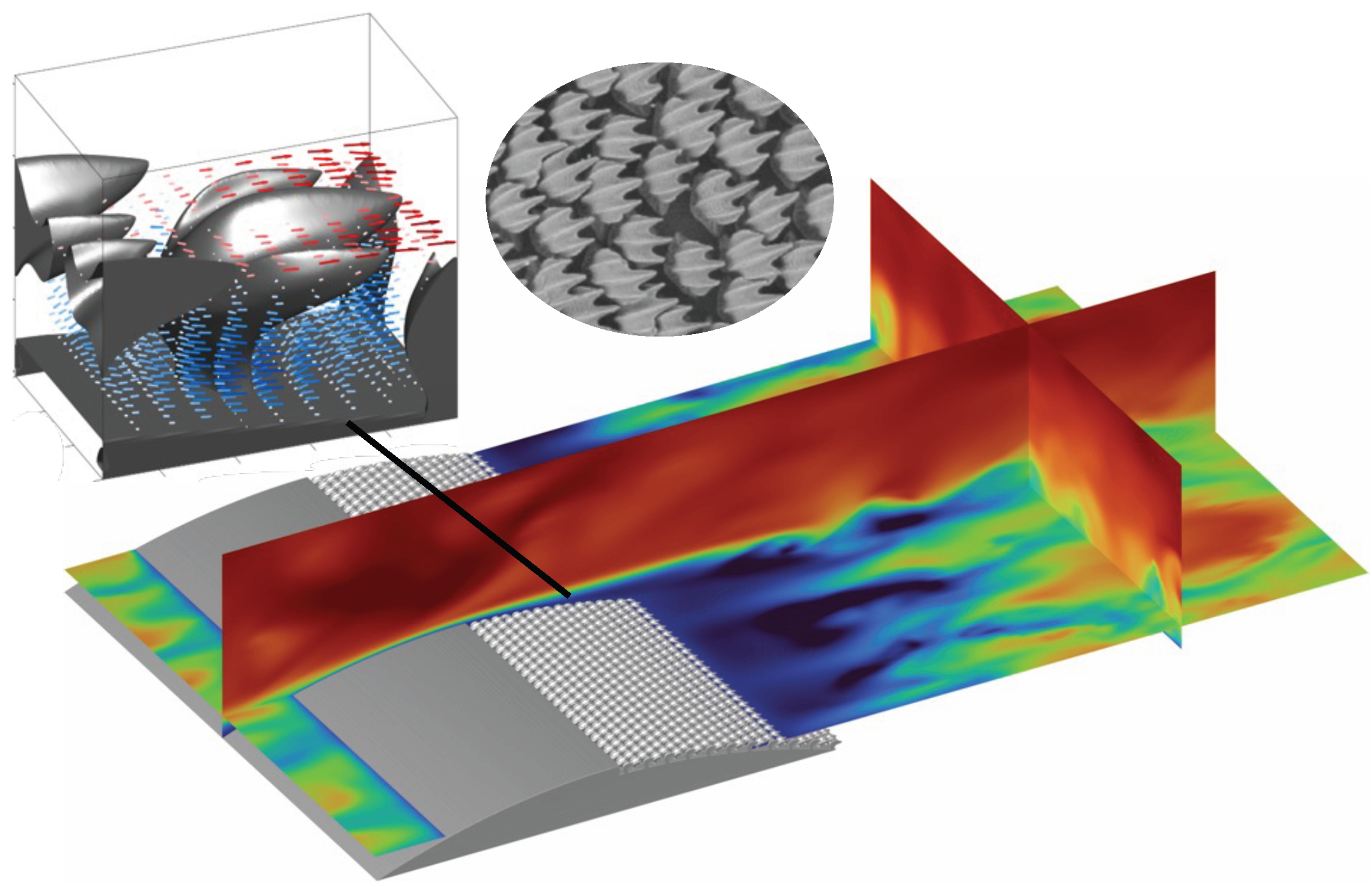

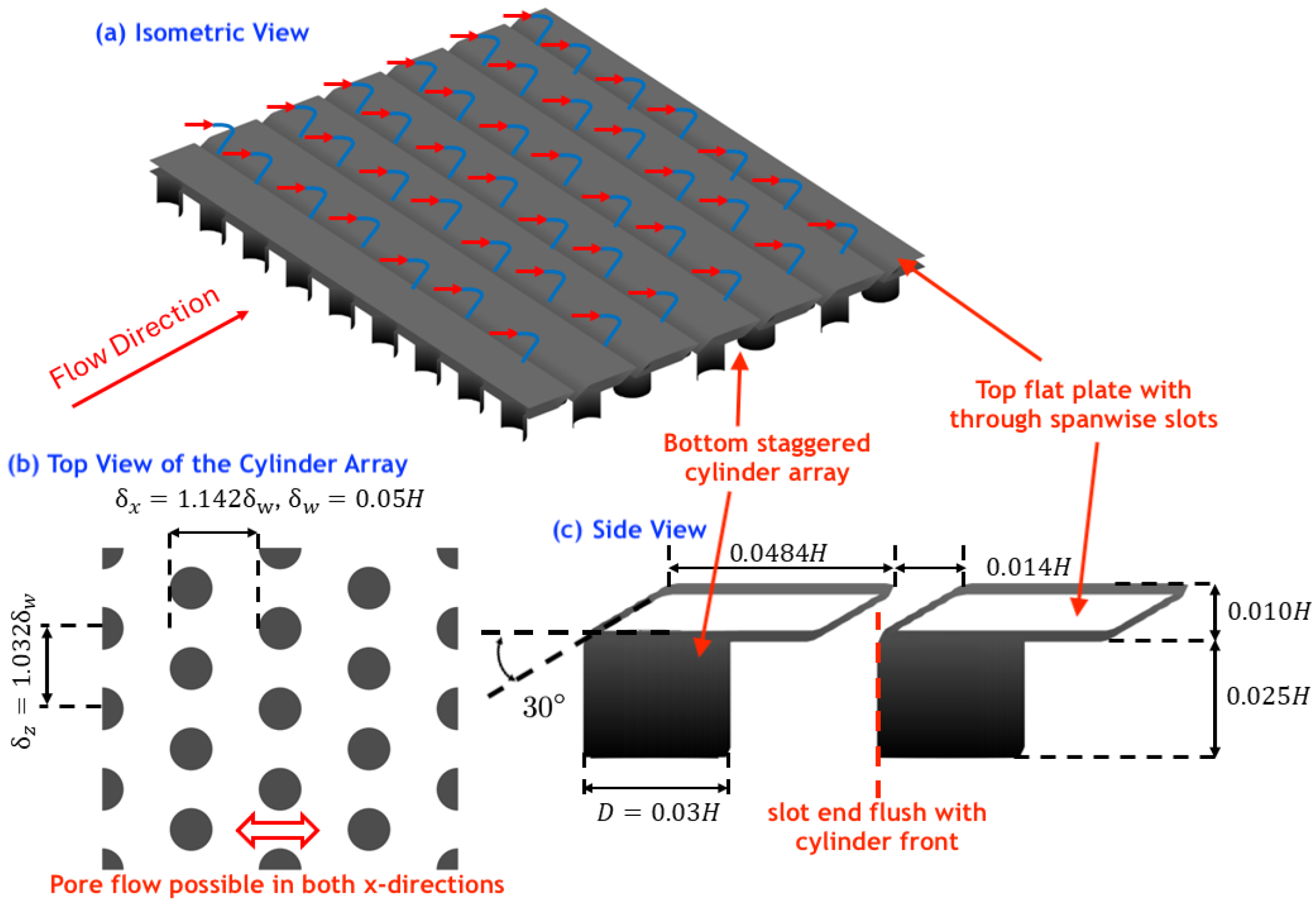

2.1. APPS Design

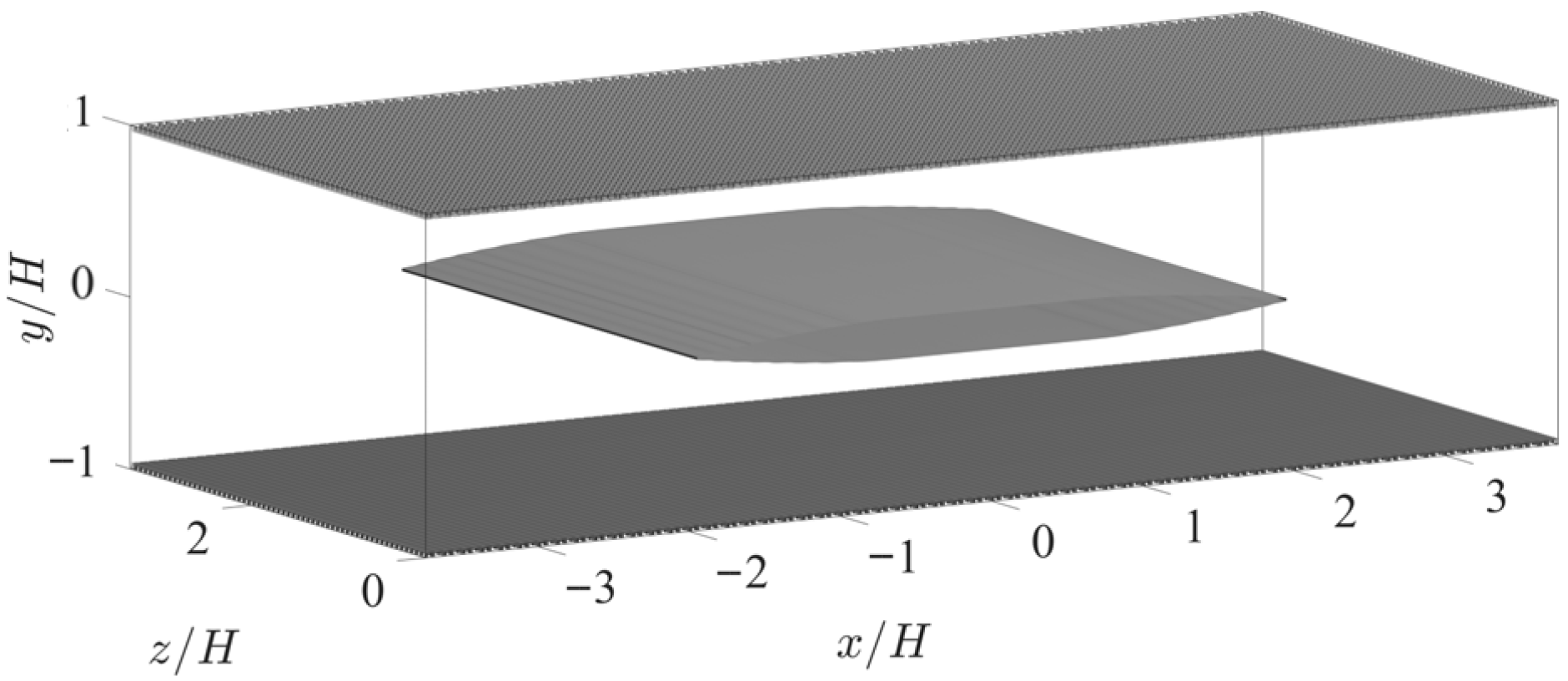

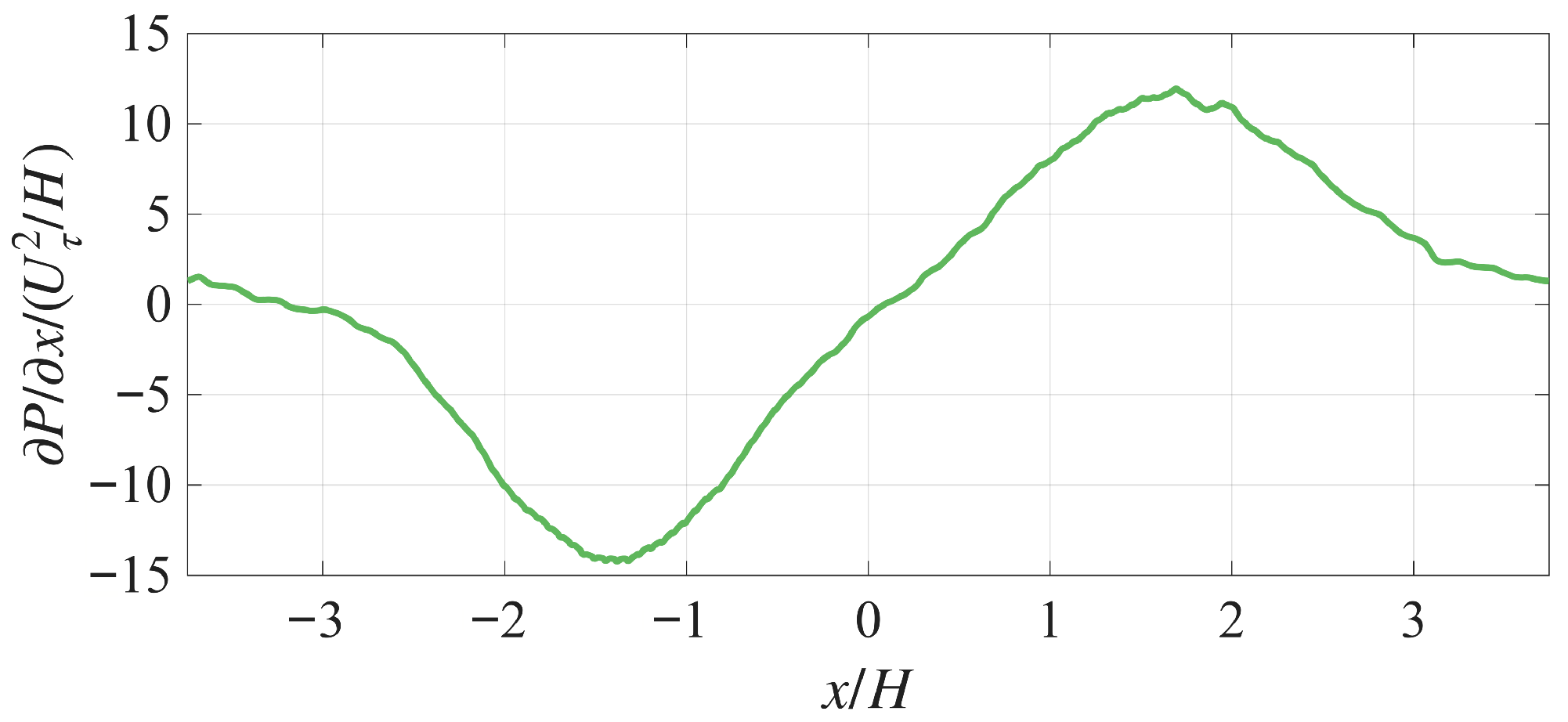

2.2. High-Fidelity Simulations

Configuration

2.3. Numerical Methods

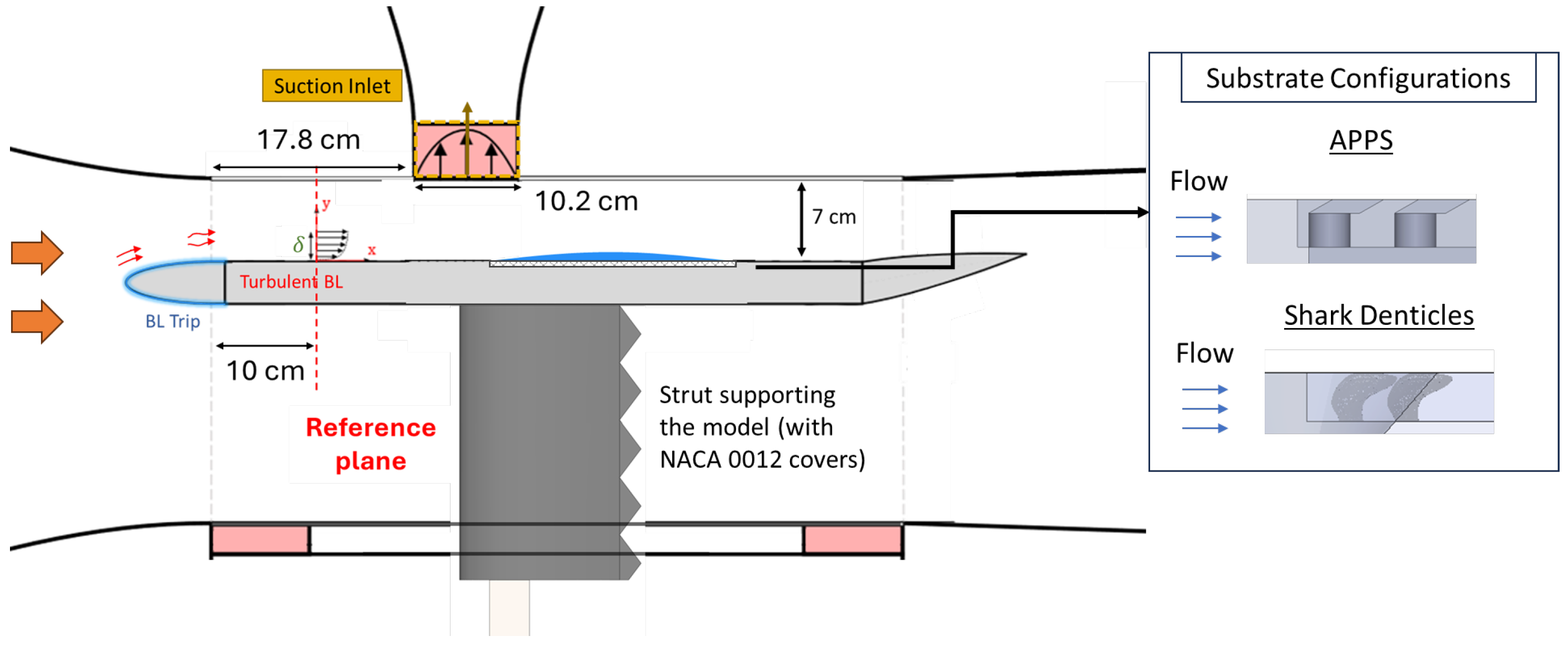

2.4. Experiments

3. Results

3.1. Simulation Results: Instantaneous Flow

3.2. Simulation Results: Mean Characteristics

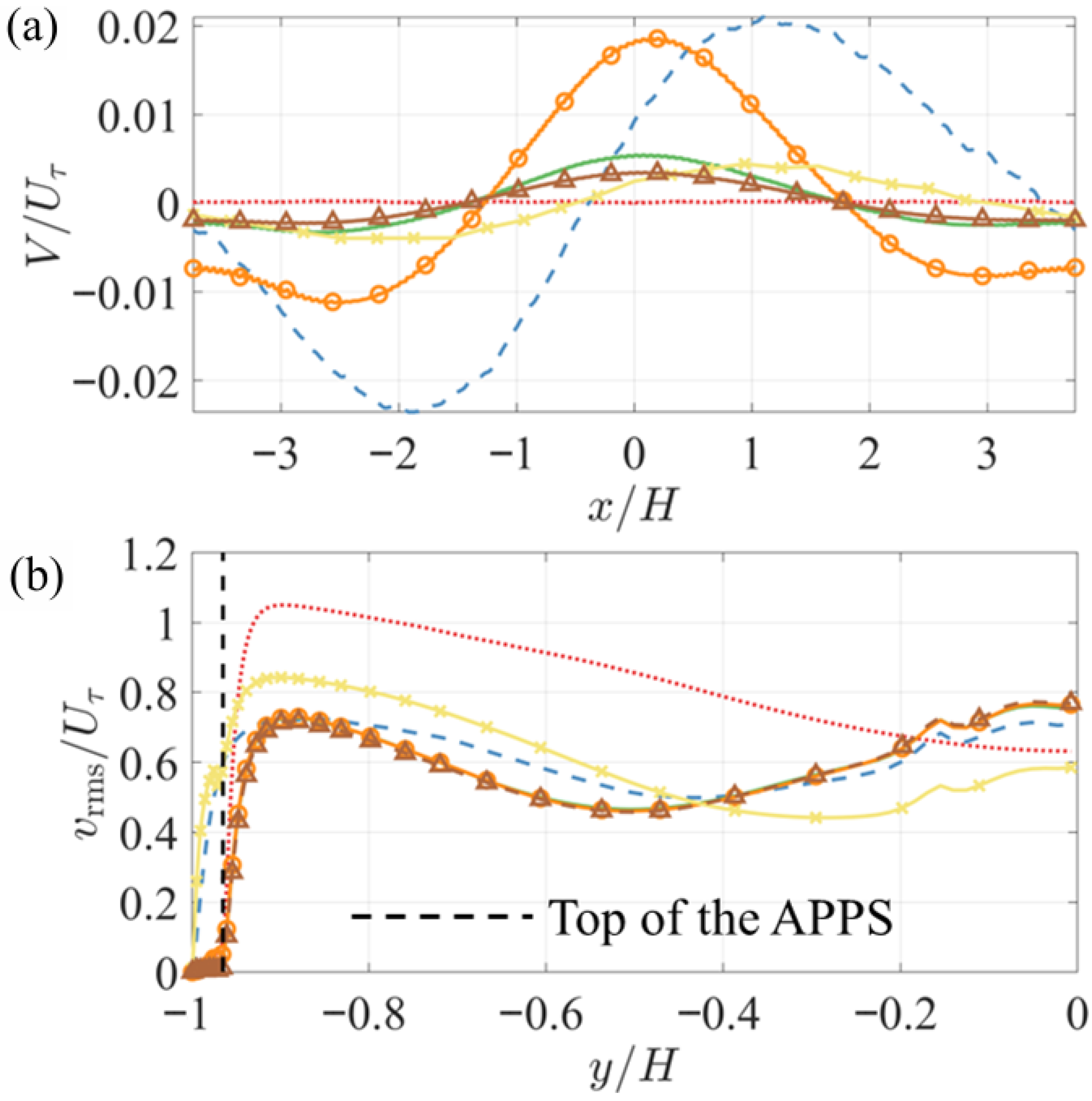

3.3. Simulation Results: Forces

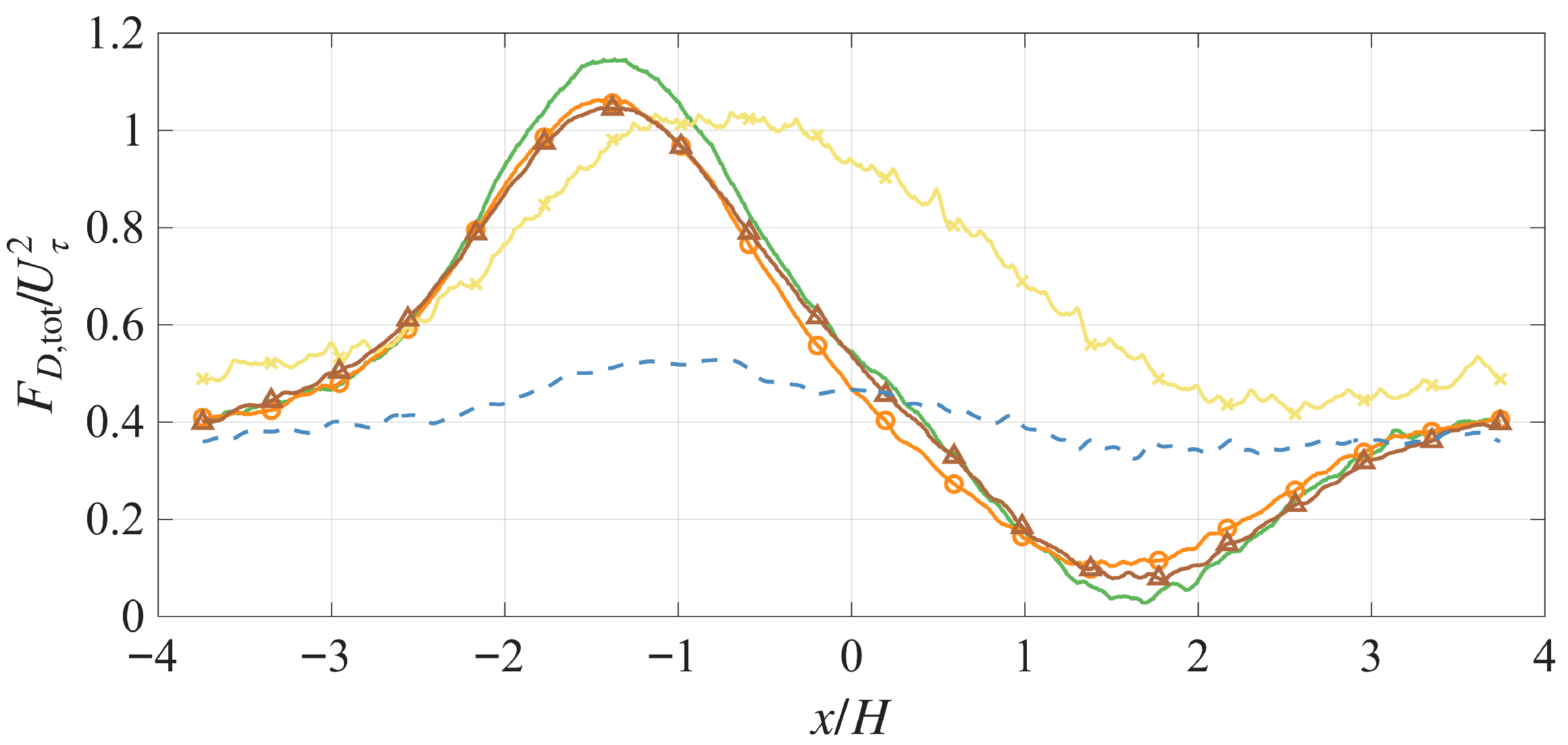

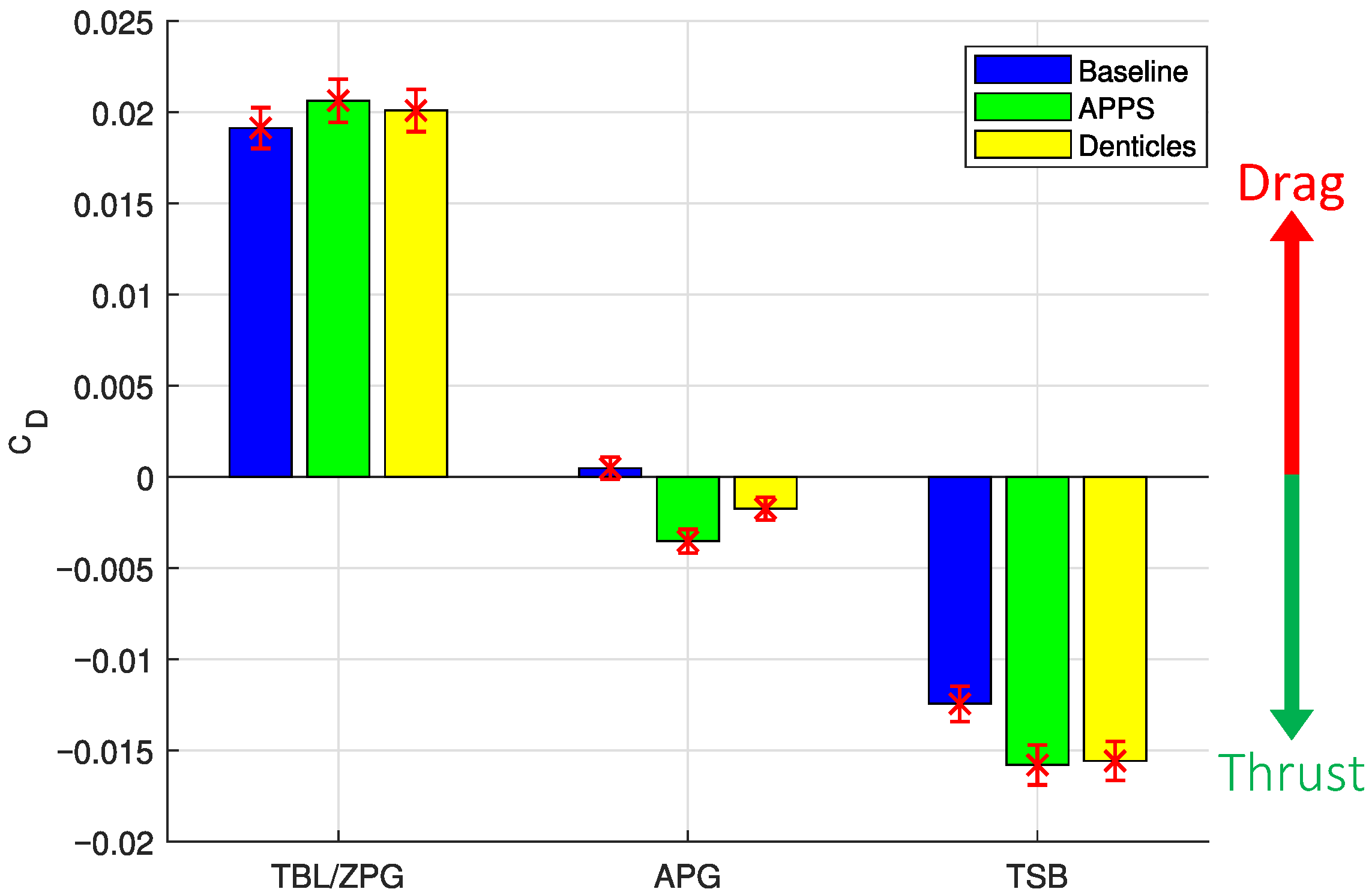

3.4. Experiment Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Boundary layer thickness | |

| APPS feature height | |

| Denticle width (following [31]) | |

| Streamwise spacing of cylinder array | |

| Spanwise spacing of cylinder array | |

| Kinematic viscosity | |

| Momentum thickness | |

| Reference planform area of the flat-plate model used in the drag coefficient definition | |

| Drag coefficient, | |

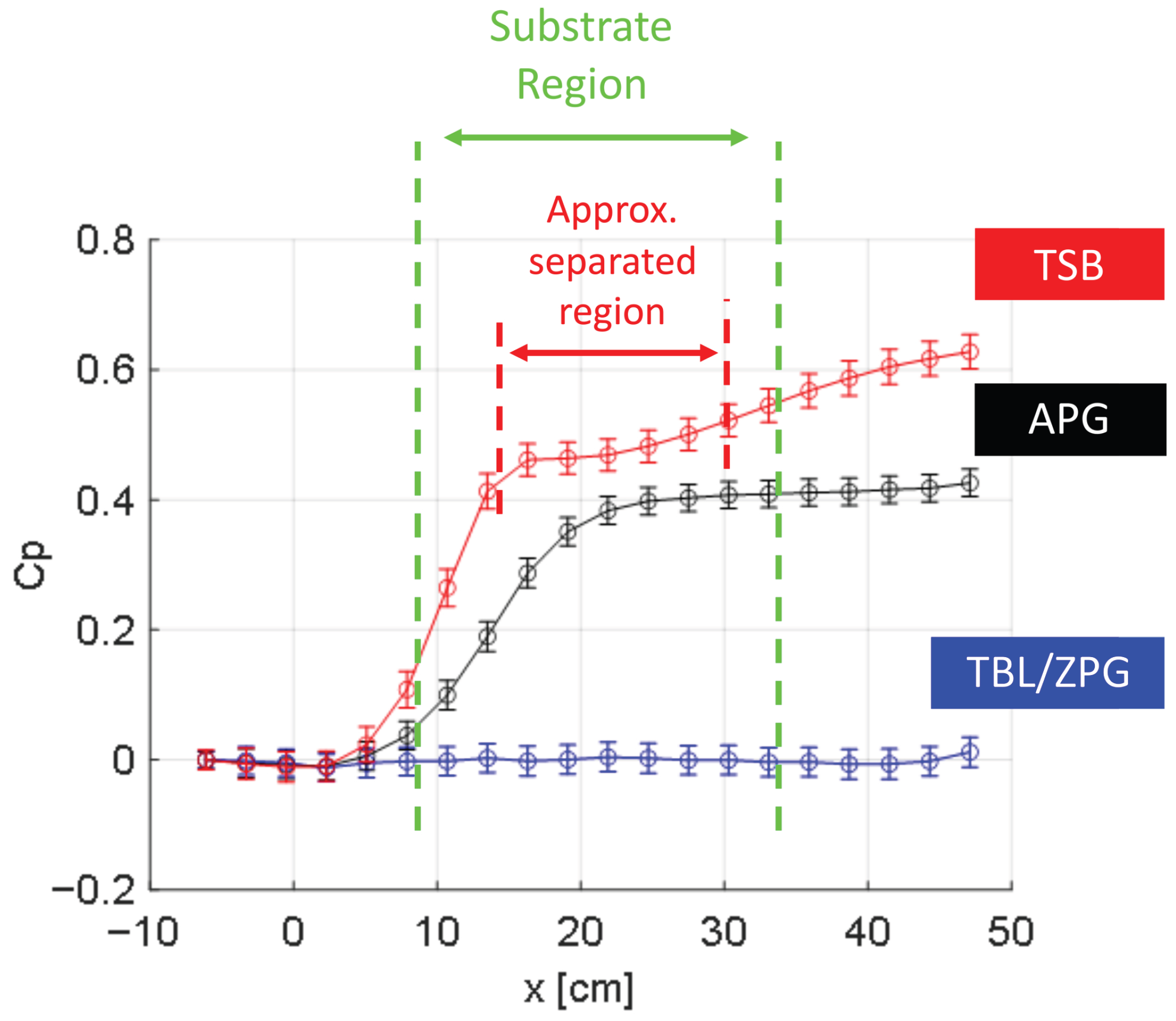

| Pressure coefficient, | |

| D | Cylinder diameter |

| Total streamwise force created by the APPS and the channel wall | |

| H | Half-channel height |

| 3D printing surface variation height in viscous units | |

| Friction Reynolds number, | |

| Momentum-thickness Reynolds number, | |

| Reynolds number based on cylinder diameter, | |

| U | Intrinsic-averaged streamwise velocity |

| u | Instantaneous streamwise velocity |

| Freestream velocity | |

| Friction velocity | |

| V | Intrinsic-averaged wall-normal velocity |

| Root-mean-square of the wall-normal velocity fluctuation | |

| x | Streamwise direction |

| y | Wall-normal direction |

| z | Spanwise direction |

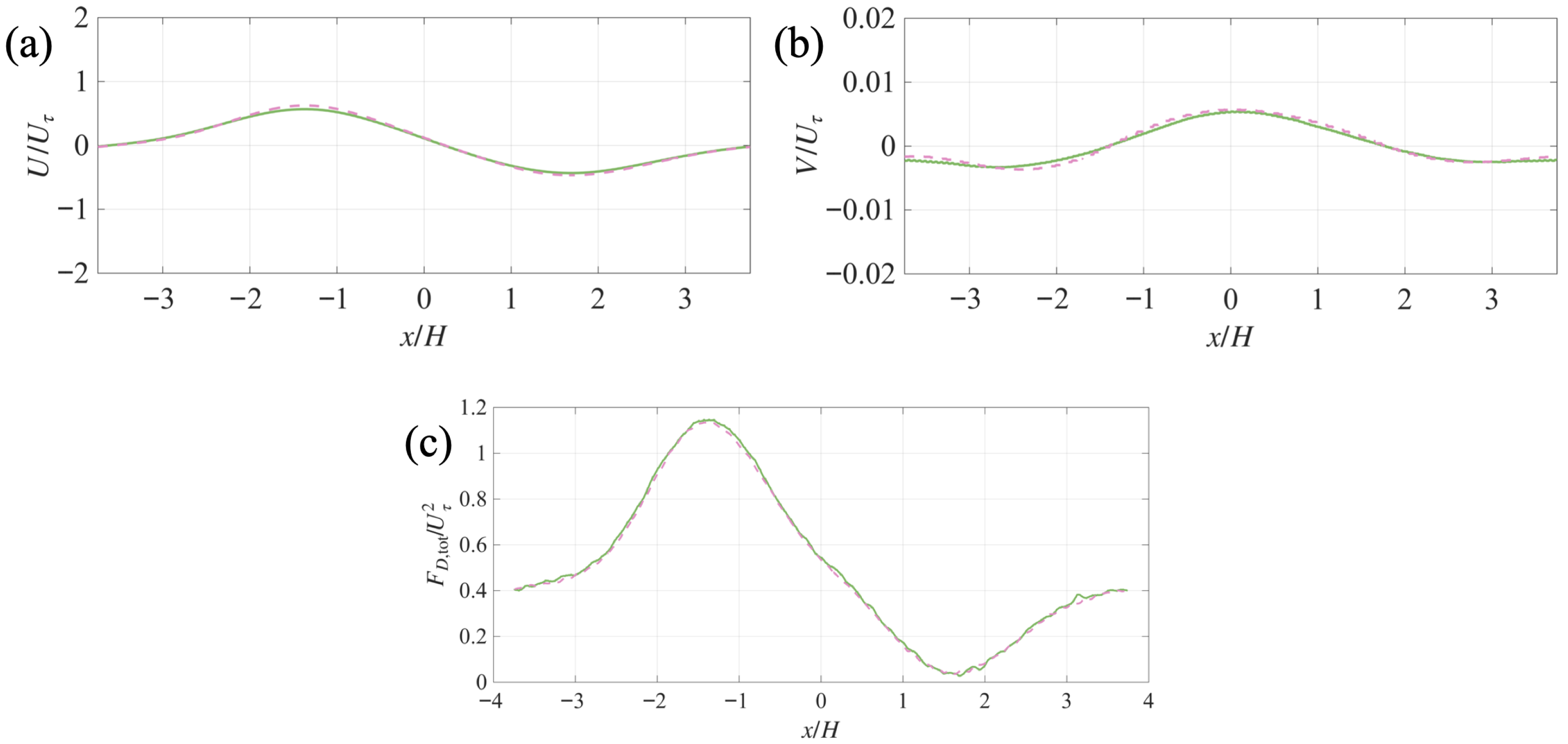

Appendix A. Grid Refinement Study

coarser grid,

coarser grid,  finer grid.

finer grid.

coarser grid,

coarser grid,  finer grid.

finer grid.

References

- Na, Y.; Moin, P. The structure of wall-pressure fluctuations in turbulent boundary layers with adverse pressure gradient and separation. J. Fluid Mech. 1998, 377, 347–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, Z.; Monty, J.P.; Mathis, R.; Marusic, I. Pressure gradient effects on the large-scale structure of turbulent boundary layers. J. Fluid Mech. 2013, 715, 477–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.K.; Zekry, D.A.; Saro-Cortes, V.; Lee, K.J.; Wissa, A.A. Aerial and aquatic biological and bioinspired flow control strategies. Commun. Eng. 2023, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, F.; Lauder, G.V. Passive and active flow control by swimming fishes and mammals. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2006, 38, 193–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Wolfgang, M.; Yue, D.; Triantafyllou, M. Three-dimensional flow structures and vorticity control in fish-like swimming. J. Fluid Mech. 2002, 468, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, A.J. Undulatory and oscillatory swimming. J. Fluid Mech. 2019, 874, P1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.i.; Kim, J.; Park, H.; Jabłoński, P.G.; Choi, H. The function of the alula in avian flight. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, M.R.; Duan, C.; Wissa, A.A. The function of the alula on engineered wings: A detailed experimental investigation of a bioinspired leading-edge device. Bioinspiration Biomimetics 2019, 14, 056015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandadzhiev, B.A.; Lynch, M.K.; Chamorro, L.P.; Wissa, A.A. An experimental study of an airfoil with a bio-inspired leading edge device at high angles of attack. Smart Mater. Struct. 2017, 26, 094008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, T.; Mohseni, K. Scaling trends of bird’s alular feathers in connection to leading-edge vortex flow over hand-wing. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mayoral, R.; Jiménez, J. Drag reduction by riblets. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2011, 369, 1412–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.S. Near-wall structure of a turbulent boundary layer with riblets. J. Fluid Mech. 1989, 208, 417–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.; Bhushan, B. Fluid flow analysis of a shark-inspired microstructure. J. Fluid Mech. 2014, 756, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechert, D.; Bruse, M.; Hage, W. Experiments with three-dimensional riblets as an idealized model of shark skin. Exp. Fluids 2000, 28, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhi, A.; Endrikat, S.; Modesti, D.; Sandberg, R.D.; Oda, T.; Tanimoto, K.; Hutchins, N.; Chung, D. Riblet-generated flow mechanisms that lead to local breaking of Reynolds analogy. J. Fluid Mech. 2022, 951, A45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modesti, D.; Endrikat, S.; Hutchins, N.; Chung, D. Dispersive stresses in turbulent flow over riblets. J. Fluid Mech. 2021, 917, A55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Moin, P.; Kim, J. Direct numerical simulation of turbulent flow over riblets. J. Fluid Mech. 1993, 255, 503–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrikat, S.; Modesti, D.; García-Mayoral, R.; Hutchins, N.; Chung, D. Influence of riblet shapes on the occurrence of Kelvin–Helmholtz rollers. J. Fluid Mech. 2021, 913, A37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mayoral, R.; Jiménez, J. Scaling of turbulent structures in riblet channels up to Reτ ≈ 550. Phys. Fluids 2012, 24, 105101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J. Turbulent flows over rough walls. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2004, 36, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, B.S.; Rouhi, A.; Wu, W. Attached Decelerating Turbulent Boundary Layers over Riblets. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.16962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumpp, S.; Guldner, T.; Meinke, M.; Schröder, W. Riblets in a turbulent adverse-pressure gradient boundary layer. In Proceedings of the 5th Flow Control Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 28 June–1 July 2010; p. 4706. [Google Scholar]

- Pargal, S.; Yuan, J.; Brereton, G. Impulse response of turbulent flow in smooth and riblet-walled channels to a sudden velocity increase. J. Turbul. 2021, 22, 353–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, A.; Sotiropoulos, F. Direct numerical simulation of sharkskin denticles in turbulent channel flow. Phys. Fluids 2016, 28, 035106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, C.; Mittal, K.; Dutta, S.; Dorrell, R.; Peakall, J.; Keevil, G.; Burns, A. Multi-fidelity modelling of shark skin denticle flows: Insights into drag generation mechanisms. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 220684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Savino, B. Dynamics of pore flow between shark dermal denticles. In CTR Annual Research Briefs; Center for Turbulence Research, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2023; pp. 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, L.; Weaver, J.C.; Lauder, G.V. Biomimetic shark skin: Design, fabrication and hydrodynamic function. J. Exp. Biol. 2014, 217, 1656–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.; Motta, P.; Hidalgo, P.; Westcott, M. Bristled shark skin: A microgeometry for boundary layer control? Bioinspiration Biomimetics 2008, 3, 046005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.W.; Bradshaw, M.T.; Smith, J.A.; Wheelus, J.N.; Motta, P.J.; Habegger, M.L.; Hueter, R.E. Movable shark scales act as a passive dynamic micro-roughness to control flow separation. Bioinspiration Biomimetics 2014, 9, 036017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.M.; Lang, A.; Wahidi, R.; Bonacci, A.; Gautam, S. Understanding Low-Speed Streaks and Their Function and Control through Movable Shark Scales Acting as a Passive Separation Control Mechanism. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, B.S.; Wu, W. Thrust generation by shark denticles. J. Fluid Mech. 2024, 1000, A80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosti, M.E.; Brandt, L.; Pinelli, A. Turbulent channel flow over an anisotropic porous wall–drag increase and reduction. J. Fluid Mech. 2018, 842, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-de Segura, G.; García-Mayoral, R. Turbulent drag reduction by anisotropic permeable substrates–analysis and direct numerical simulations. J. Fluid Mech. 2019, 875, 124–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-de Segura, G.; Sharma, A.; García-Mayoral, R. Turbulent drag reduction using anisotropic permeable substrates. Flow, Turbul. Combust. 2018, 100, 995–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abderrahaman-Elena, N.; García-Mayoral, R. Analysis of anisotropically permeable surfaces for turbulent drag reduction. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2017, 2, 114609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; García-Mayoral, R. Turbulent flows over porous and rough substrates. J. Fluid Mech. 2025, 1008, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, A.; Piomelli, U.; Bremhorst, K.; Nešić, S. Large-eddy simulation of heat transfer downstream of a backward-facing step. J. Turbul. 2004, 5, N20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Piomelli, U.; Yuan, J. Turbulence statistics in rotating channel flows with rough walls. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2019, 80, 108467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Piomelli, U. Roughness effects on the Reynolds stress budgets in near-wall turbulence. J. Fluid Mech. 2014, 760, R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Piomelli, U. Numerical simulation of a spatially developing accelerating boundary layer over roughness. J. Fluid Mech. 2015, 780, 192–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Piomelli, U. Numerical simulations of sink-flow boundary layers over rough surfaces. Phys. Fluids 2014, 26, 015113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, R.D.; Kim, J.; Mansour, N.N. Direct numerical simulation of turbulent channel flow up to Reτ = 590. Phys. Fluids 1999, 11, 943–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Kanov, K.; Yang, X.I.A.; Lee, M.; Malaya, N.; Lalescu, C.C.; Burns, R.; Eyink, G.; Szalay, A.; Moser, R.D.; et al. A Web services accessible database of turbulent channel flow and its use for testing a new integral wall model for LES. J. Turbul. 2016, 17, 181–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Moser, R.D. Direct numerical simulation of turbulent channel flow up to Reϕ ≈ 5200. J. Fluid Mech. 2015, 774, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.N.; Fenelon, M.R.; Zhang, Y.; Cattafesta, L.N.; Richardson, R.; Mittal, R.; Meneveau, C.; Aghaei-Jouybari, M.; Seo, J.H. The Effects of Anisotropic Porous Lattice Substrates on Turbulent Separation Bubbles. In Proceedings of the AIAA AVIATION 2024 FORUM, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 29 July–2 August 2024; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, R.; Zhang, Y.; Cattafesta, L. Low-dimensional dynamics of a turbulent separation bubble. In Proceedings of the AIAA SCITECH 2023 Forum, National Harbor, MD, USA, 23–27 January 2023; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, S.N.; Zhang, Y.; Cattafesta, L.N.; Mittal, R.; Meneveau, C.; Luhar, M.; Aghaeijouybari, M.; Seo, J.H.; Vijay, S.; Eizenberg, I. Characterization of Periodic Lattice Anisotropic Porous Materials for Passive Flow Control. In Proceedings of the AIAA AVIATION 2023 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–16 June 2023; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aghaei-Jouybari, M.; Seo, J.H.; Pinto, S.; Cattafesta, L.; Meneveau, C.; Mittal, R. Extended Darcy–Forchheimer law including inertial flow deflection effects. J. Fluid Mech. 2024, 980, A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formlabs. Form 4L 3D Printer Tech Specs Comparison. 2025. Available online: https://formlabs.com/3d-printers/resin/tech-specs/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Zhang, L.; Balachandar, S. Onset of Vortex Shedding in a Periodic Array of Circular Cylinders. J. Fluids Eng. 2006, 128, 1101–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, Z.; Pocher, L.; Tilton, N. Regimes of flow through cylinder arrays subject to steady pressure gradients. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 159, 120072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.J.; Koch, D.L.; Ladd, A.J. Moderate-Reynolds-number flows in ordered and random arrays of spheres. J. Fluid Mech. 2001, 448, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, J.; Weitzenfeld, A.; Baca, J.; García, C.; Cecilia, E. Aerospace Bionic Robotics: BEAM-D Technical Standard of Biomimetic Engineering Design Methodology Applied to Mechatronics Systems. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

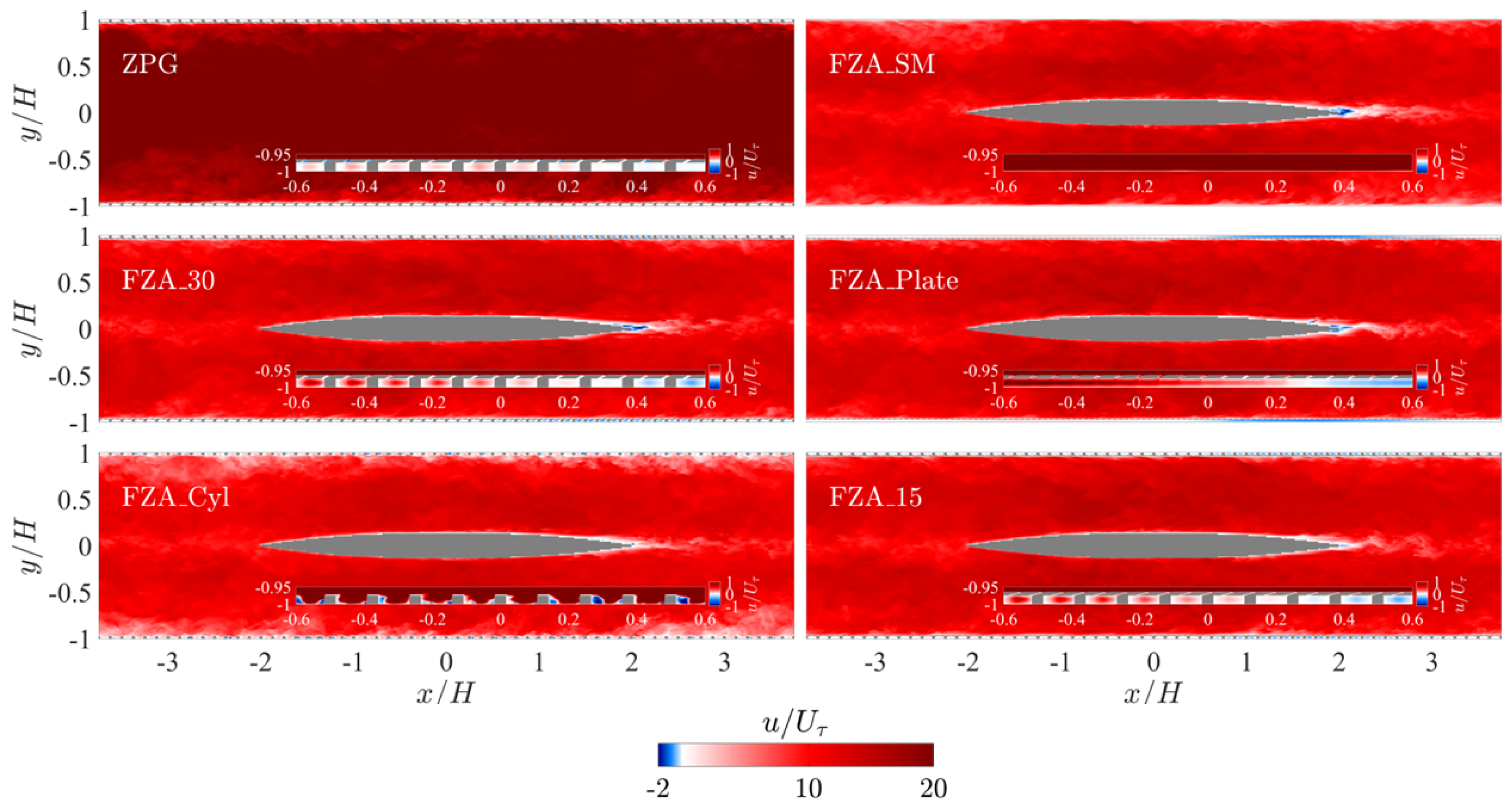

ZPG,

ZPG,  FZA_30,

FZA_30,  FZA_Plate,

FZA_Plate,  FZA_Cyl,

FZA_Cyl,  FZA_15.

FZA_15.

ZPG,

ZPG,  FZA_30,

FZA_30,  FZA_Plate,

FZA_Plate,  FZA_Cyl,

FZA_Cyl,  FZA_15.

FZA_15.

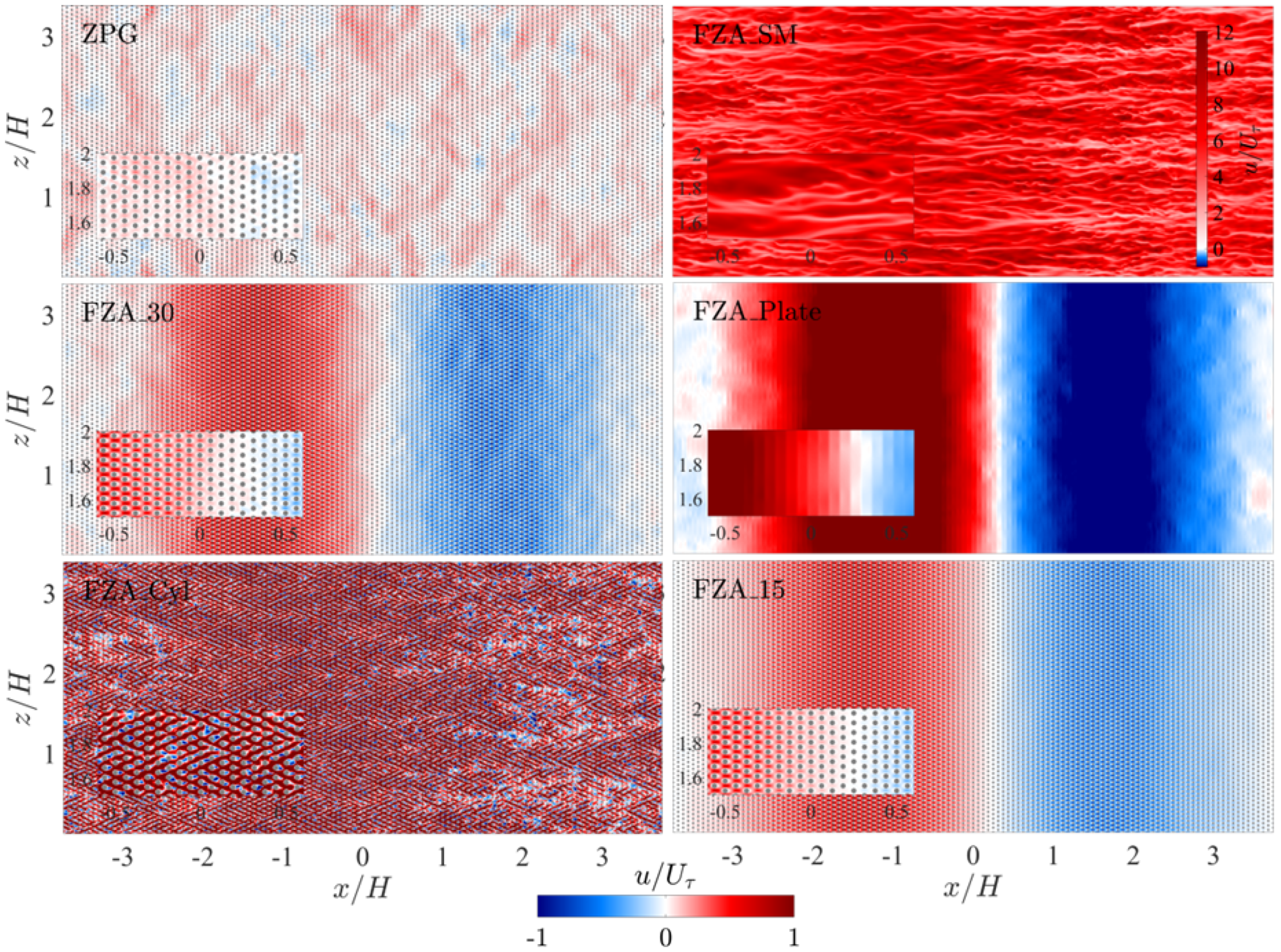

ZPG,

ZPG,  FZA_SM,

FZA_SM,  FZA_30,

FZA_30,  FZA_Plate,

FZA_Plate, FZA_Cyl,

FZA_Cyl,  FZA_15.

FZA_15.

ZPG,

ZPG,  FZA_SM,

FZA_SM,  FZA_30,

FZA_30,  FZA_Plate,

FZA_Plate, FZA_Cyl,

FZA_Cyl,  FZA_15.

FZA_15.

FZA_SM,

FZA_SM,  FZA_30,

FZA_30,  FZA_Plate,

FZA_Plate,  FZA_Cyl,

FZA_Cyl,  FZA_15.

FZA_15.

FZA_SM,

FZA_SM,  FZA_30,

FZA_30,  FZA_Plate,

FZA_Plate,  FZA_Cyl,

FZA_Cyl,  FZA_15.

FZA_15.

| Case Name | Channel Insert | Features | Configuration Schematic |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZPG | No | Full APPS |

|

| FZA_SM | Yes | No APPS |

|

| FZA_30 | Yes | Full APPS |

|

| FZA_Cyl | Yes | Cylinder only |

|

| FZA_Plate | Yes | Top plate only |

|

| FZA_15 | Yes | Full APPS, 15° slots |

|

| (m/s) | (mm) | Shape Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBL | 14.7 | 6.99 | 782 | 1.62 |

| APG | 14.8 | 6.99 | 810 | 1.60 |

| TSB | 13.7 | 6.93 | 762 | 1.68 |

| mm | Normalized by | Normalized by | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total height | 1.00 | 0.143 (0.035) | 38.2 (52.5) |

| Cylinder height | 0.714 | 0.102 (0.025) | 27.3 (37.5) |

| Cylinder diameter | 0.857 | 0.122 (0.030) | 32.8 (45.0) |

| Top plate thickness | 0.286 | 0.0409 (0.010) | 10.9 (15.0) |

| Slot width | 0.400 | 0.0571 (0.014) | 15.3 (21.0) |

| Slot spacing | 1.78 | 0.254 (0.0484) | 68.0 (93.6) |

| Case | TBL | APG | TSB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flat Plate | |||

| APPS | |||

| Shark Denticles (SD) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cooper, B.K.; Pinto, S.; Hong, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cattafesta, L.; Wu, W. DNS and Experimental Assessment of Shark-Denticle-Inspired Anisotropic Porous Substrates for Drag Reduction. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120838

Cooper BK, Pinto S, Hong H, Zhang Y, Cattafesta L, Wu W. DNS and Experimental Assessment of Shark-Denticle-Inspired Anisotropic Porous Substrates for Drag Reduction. Biomimetics. 2025; 10(12):838. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120838

Chicago/Turabian StyleCooper, Benjamin Kellum, Sasindu Pinto, Henry Hong, Yang Zhang, Louis Cattafesta, and Wen Wu. 2025. "DNS and Experimental Assessment of Shark-Denticle-Inspired Anisotropic Porous Substrates for Drag Reduction" Biomimetics 10, no. 12: 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120838

APA StyleCooper, B. K., Pinto, S., Hong, H., Zhang, Y., Cattafesta, L., & Wu, W. (2025). DNS and Experimental Assessment of Shark-Denticle-Inspired Anisotropic Porous Substrates for Drag Reduction. Biomimetics, 10(12), 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120838