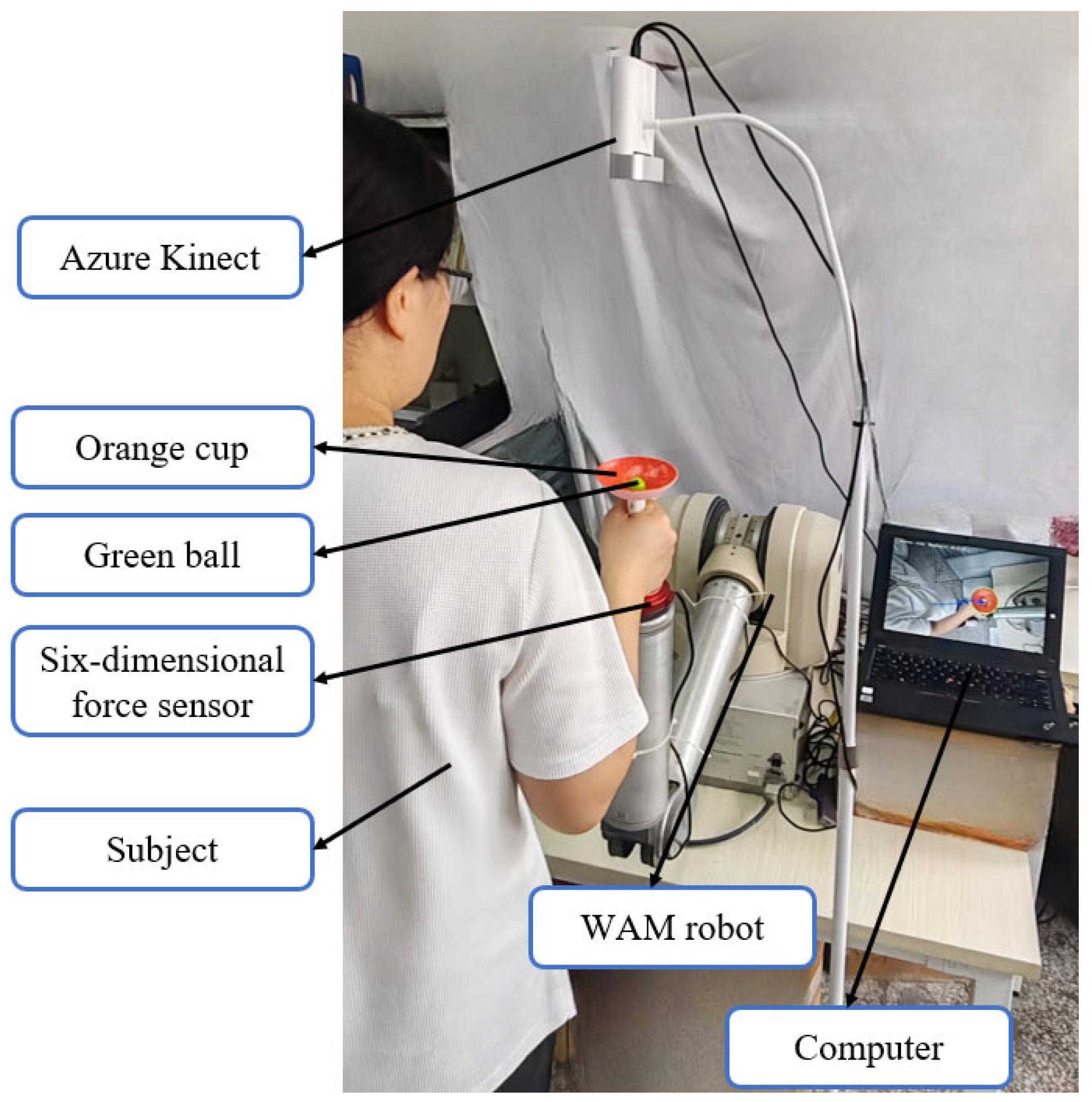

The structure of the innovative robotic training system for occupational therapy proposed in this study is illustrated in

Figure 1. The system utilizes a WAM (Whole Arm Manipulator, Barrett Technology, Newton, MA, USA) robotic arm as the platform, with a simplified “cup–ball system” (comprising a hemispherical cup and a small ball inside) attached to the end-effector. The motion trajectory of the ball is captured using an Azure Kinect sensor (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). To simulate the dynamic challenges of “carrying a liquid-filled cup” in occupational therapy, an integrated approach combining exponential filtering, force compensation, and impedance control is employed to suppress ball oscillations. This system assists patients in occupational therapy by progressively enhancing their perception and control capabilities regarding liquid sloshing dynamics.

3.1. Mathematical Model of the Cup Ball System

Refer to the transportation coffee experimental platform developed by Sternad et al. [

31,

32], a hemispherical cup–ball system is designed to enable the robotic arm to assist patients in relearning fine motor skills, specifically the perception-control loop for ball-simulated liquid sloshing, thereby enhancing their functional interaction capacity during daily activities. A small, physical ball is used instead of liquid “coffee”, and the coffee cup is simplified into a hemispherical cup. The bottom of the cup is connected to the mechanical arm through a flange. This setup requires the patient to perform the functional task of moving the cup with robot arm assistance while preventing the ball from falling out, training the ability to dynamically integrate motor commands with sensory feedback.

Assisted by the robotic arm, the subject moves the cup via a handle. A rightward displacement of the cup (along the positive x-axis) is defined as positive, and a clockwise swing of the ball along the cup’s inner arc is defined as a positive increase in its slosh angle. Through a resultant force (Fext) applied to the cup, the robotic arm assists the subject in controlling the cup position (xc). During the movement, the system directly perceives the interaction force between the ball and the cup. Simultaneously, the arm can employ gravity compensation to counteract the cup’s weight, thereby simulating the real-world activity of carrying a cup of water.

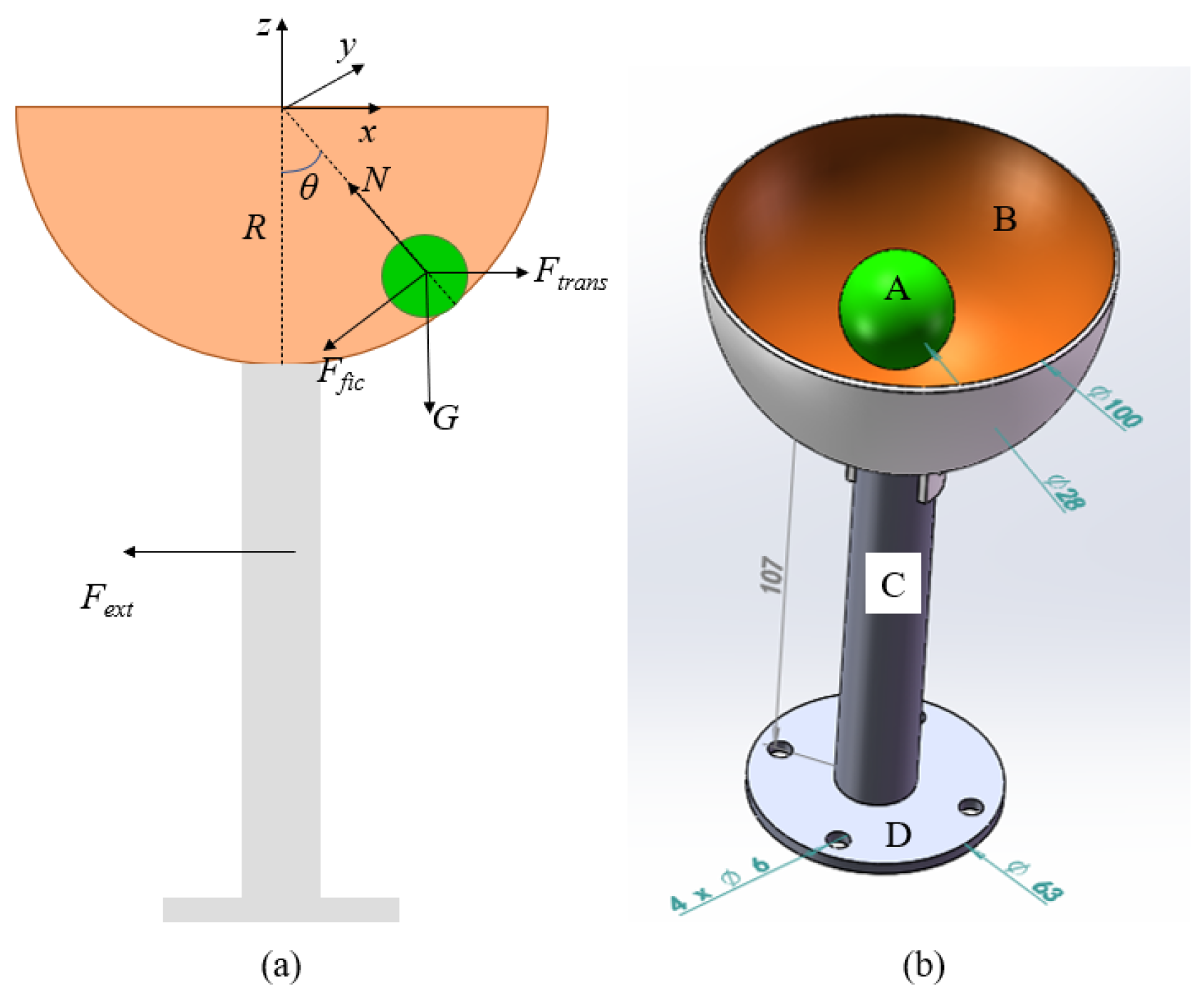

The force analysis of the ball-and-cup system is shown in

Figure 2a. The ball is primarily subject to the normal force (N) from the cup, gravity (G), friction force (

Ffic), and inertial force (

Ftrans). The three-dimensional model of the system is presented in

Figure 2b. Taking the center of the hemisphere cup as the origin, the angle between the normal force acting on the ball and the direction of gravity is

θ, which characterizes the sloshing motion of the ball. This angle is referred to as the slosh angle of the ball. To simplify the analysis, the motion of the ball is approximated as that of a constrained particle. The mass of the ball is

m, and a coordinate system is established with the center of the hemisphere as the origin. The position of the ball in the hemisphere cup

is as shown in Equation (1).

where

R is the radius of the hemispherical cup,

θ represents the polar angle, also referred to as the slosh angle (when

θ = 0, the ball is at the bottom of the cup, 0 ≤

θ ≤ π/2), and

φ represents the azimuth angle (0 ≤

φ ≤ 2π). The kinetic energy of the ball is given by Equation (2). With the center of the hemispherical cup (

z = 0, corresponding to the ball’s position at

θ = π/2) set as the zero potential energy reference, the gravitational potential energy of the ball is expressed by Equation (3).

The Lagrangian function is constructed as follows:

As the cup is accelerated, the ball’s force balance in this co-moving non-inertial frame comprises inertial force effects. The equation for the generalized force balance is expressed as Equation (5).

where

represents the inertial force arising from the ball’s relative acceleration within the cup-fixed frame of reference. g is the gravitational acceleration. The non-inertial force term is given as follows:

is the inertial force caused by the translational acceleration of the cup;

denotes the Euler force arising from the angular acceleration of the cup;

represents the Coriolis force; and

represents Centrifugal force. To simplify the analysis, the rotation of the hemispherical cup is neglected; thus, all terms related to angular velocity disappear.

In the dynamic equation, the constraint force only appears in the normal direction, while the motion in the tangential direction is determined by the applied force. According to D’Alembert’s Principle, the constraint force does no work, so the motion of the ball in the tangential plane of the cup–ball system will not be affected. The tangent plane in spherical coordinates is defined by two unit vectors, in the direction of increasing θ, and in the direction of increasing φ. These two vectors are orthogonal to each other. We project the motion equation of the ball onto the tangent plane, and the normal constraint force N is eliminated, thereby obtaining the tangential motion, which is the equations in the θ and φ directions. Thus, the original three-dimensional motion problem is transformed into a two-dimensional problem of motion within the tangent plane.

In the spherical coordinate system, variations in the

θ and

φ directions precisely describe the motion of the ball on a curved surface. Motion in the

θ direction corresponds to the ball moving along the meridian, while motion in the

φ direction corresponds to the ball moving along the parallel. Projecting

onto the

and

directions:

The gravitational and cup acceleration terms are given by Equation (7):

We adopt a simple viscous friction model:

, where

is the coefficient of viscous friction. Projecting the frictional force onto the tangential direction:

Substituting the above results into the tangential equations yields the dynamic equations in the

θ direction and

φ direction, as shown in Equation (9).

where

,

represents the acceleration of the cup. When

θ is very small (that is, when the ball is close to the bottom of the cup),

,

, the higher-order terms of

and

can be neglected. Thus, the dynamic equation can be simplified to Equation (10).

The equation has a singularity when

θ ≈ 0 in the φ direction. Therefore, the dynamics of the azimuthal angle become unstable when the ball approaches the center of the cup. In practice, however, since the azimuth angle is inconsequential and does not contribute to the ball spilling out when it is near the bottom of the cup, its motion can be neglected. For the radial motion of the ball (in the

θ direction), an approximate linear equation is obtained as shown in Equation (11), and this mathematical model is equivalent to a general second-order equation.

where

.

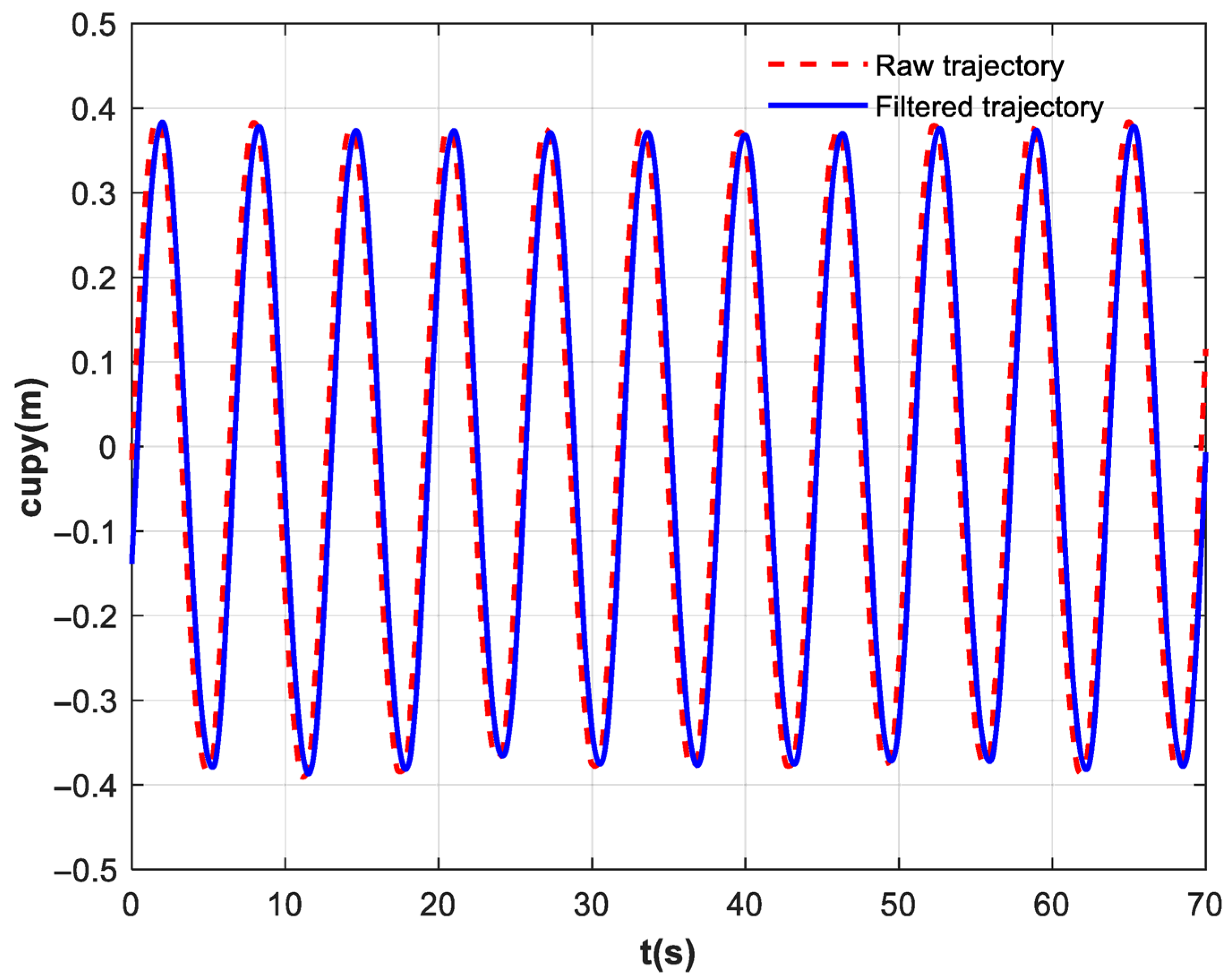

3.2. Visual Tracking Algorithm

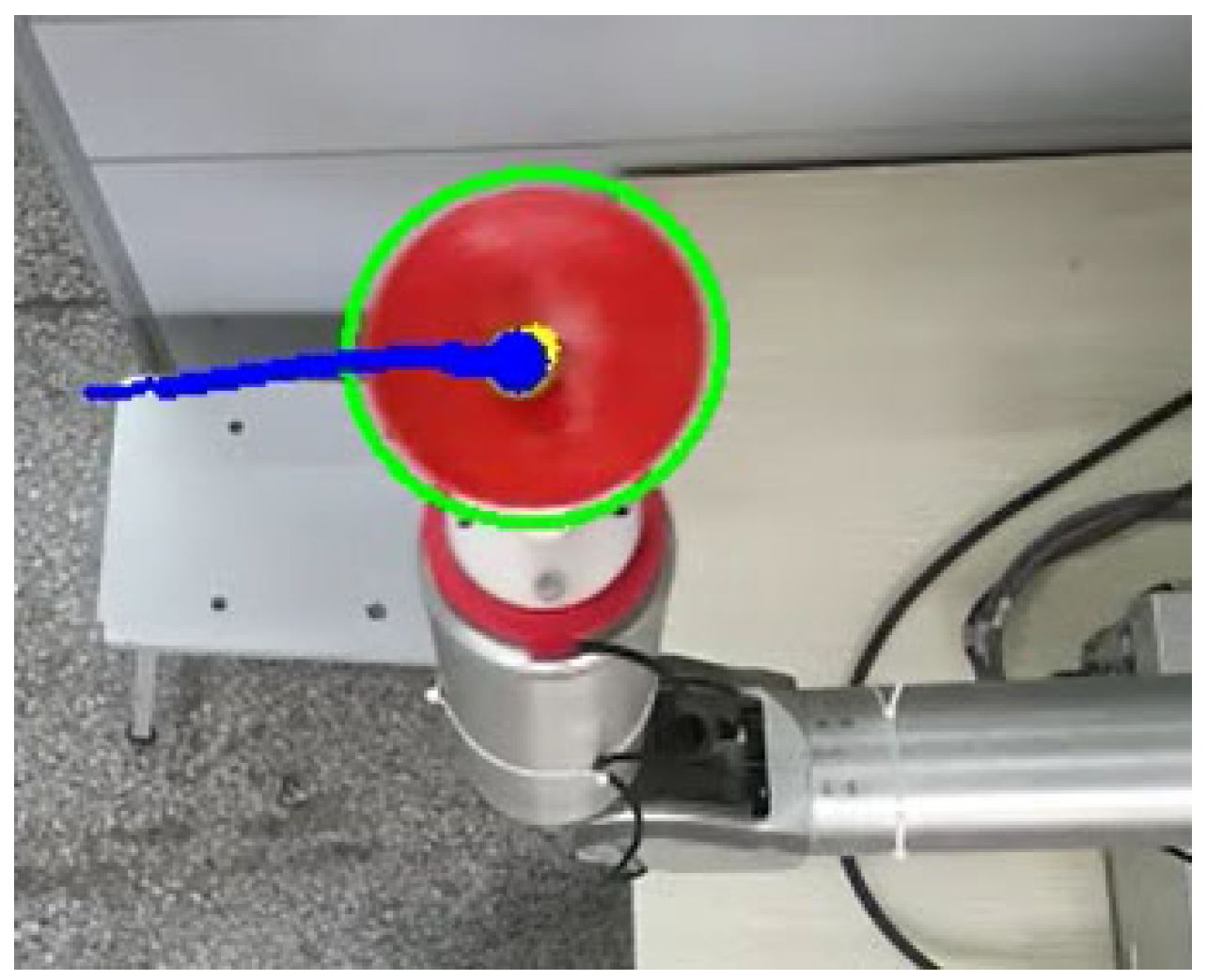

The trajectories of the ball and the cup are tracked using an Azure Kinect camera, which is installed vertically directly above the ball-and-cup system. The Azure Kinect provides a spatial positioning accuracy within 0.5–2 m and a depth error of less than 2 mm in the optical center region, thereby meeting the precision requirements for tracking the system. Color and depth images of the ball (simulating liquid sloshing) and the cup (at the handle) are captured synchronously. A built-in camera calibration tool from the Kinect SDK is used with a printed checkerboard pattern to establish a mapping between RGB and depth pixels, ensuring one-to-one coordinate correspondence for the same target in both image modalities. RGB images at a resolution of 640 × 580 enable color-based segmentation, while depth images are used to distinguish the target from the background and filter out occlusions.

For accurate tracking of the ball and cup, the interior of the cup is designed to be orange, while the ball is green. Using depth data for image pre-processing, specific Hue, Saturation, Value (HSV) thresholds are defined for both the orange cup and the green ball to generate their respective binary masks, enabling initial extraction of the target regions via RGB color segmentation. Depth data are then utilized to create a region-of-interest (ROI) mask, which excludes background interference such as the patient’s hand and the table edge. The color mask and the depth mask are combined using a logical AND operation to produce a refined mask that contains only the pixels within the target color and depth ranges. Median filtering is applied to the depth image to suppress salt-and-pepper noise inherent in the Kinect depth data. For the resulting fused binary mask, one iteration of erosion with a 5 × 5 kernel is first applied to remove fine noise, followed by two iterations of dilation with the same kernel to restore the original target contours.

Subsequently, target detection and tracking are performed. The contour of the cup is extracted from the fused mask, and an ellipse is fitted using the fitEllipse algorithm to determine the initial center coordinates along with the lengths of the major and minor axes. In the depth image, a 10 × 10-pixel region centered on these coordinates is selected, and the average depth is calculated. By applying a predefined depth threshold, the movement mode of the cup is determined. Based on the elliptical fitting result of the cup, an ROI is delineated in the depth image. Within this ROI, a depth threshold is set to extract pixels with depth values less than or equal to that of the ball, generating a candidate region for ball detection. The HoughCircles algorithm is then applied to detect circular shapes within this candidate region. The detected circles are matched to the actual size of the ball, and those with a radius of approximately 100 mm are selected to identify the ball’s center coordinates.

To enhance tracking performance, a Kalman filter is employed for parameter optimization. It utilizes the velocity and acceleration from the previous frame to predict the current position, thereby reducing motion lag caused by low frame rates and improving the stability of depth data. The visual tracking result is shown in

Figure 3, where the green ellipse represents the cup contour, the yellow points mark the center of the ball, and the blue curve illustrates the trajectory of the ball.

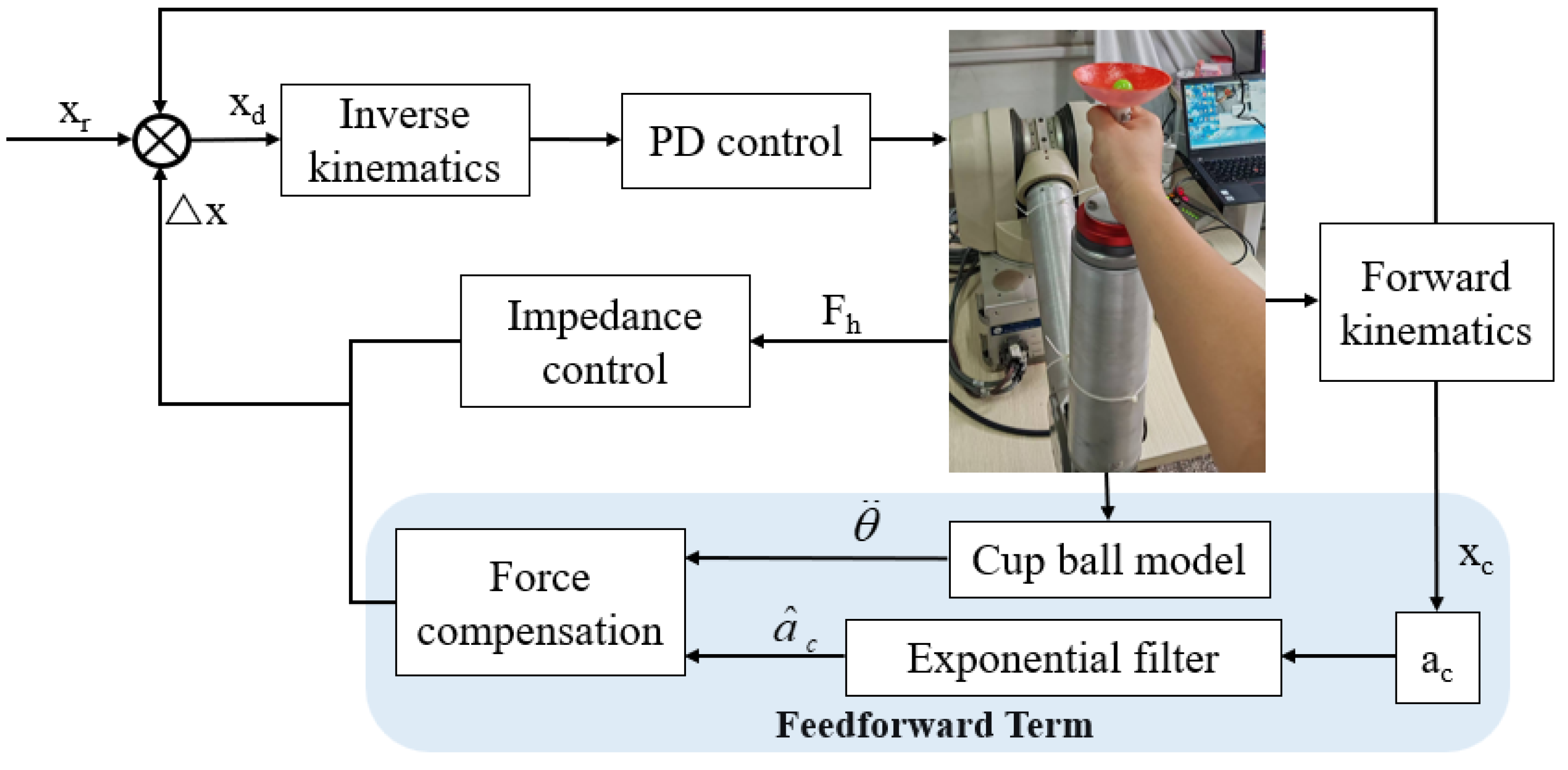

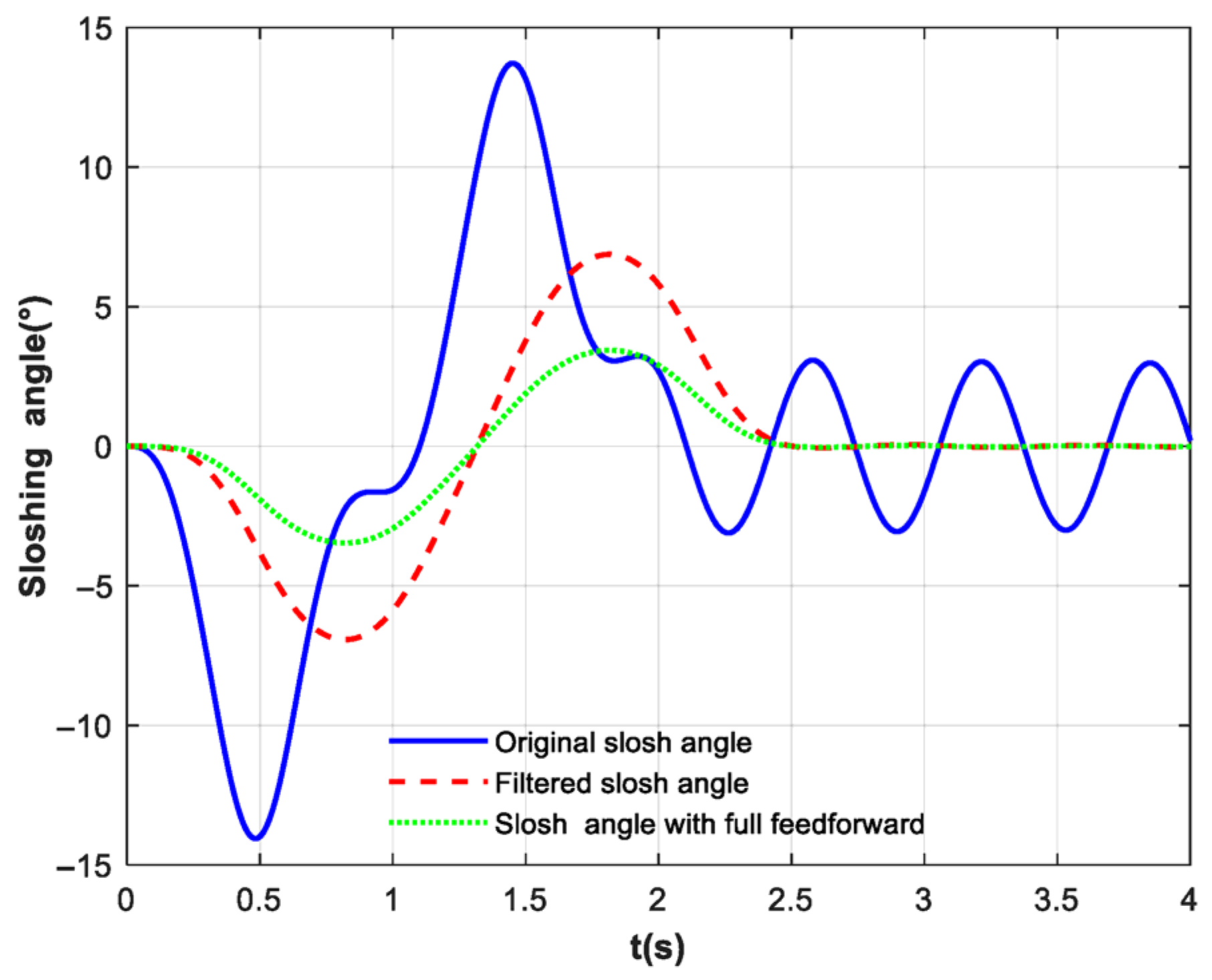

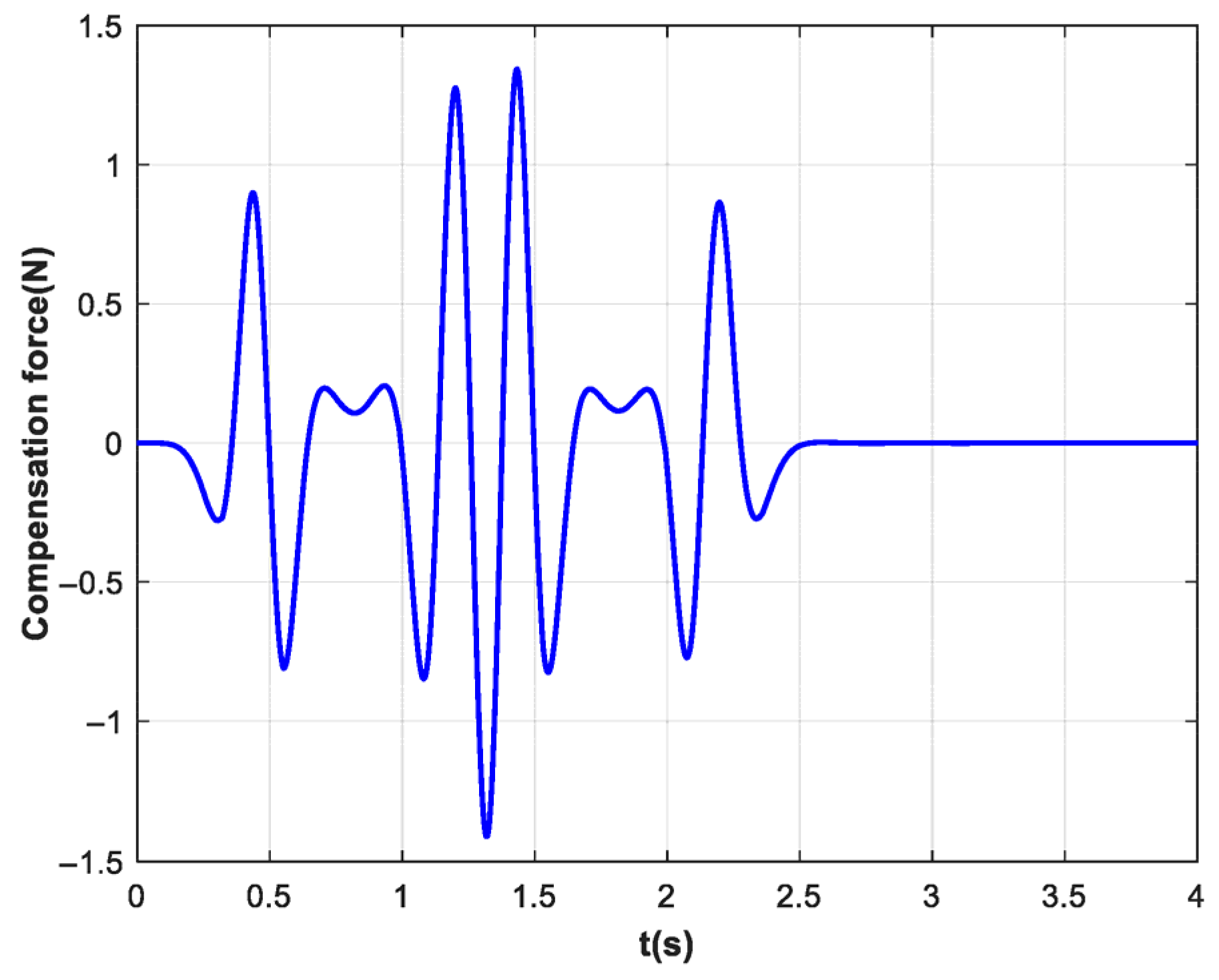

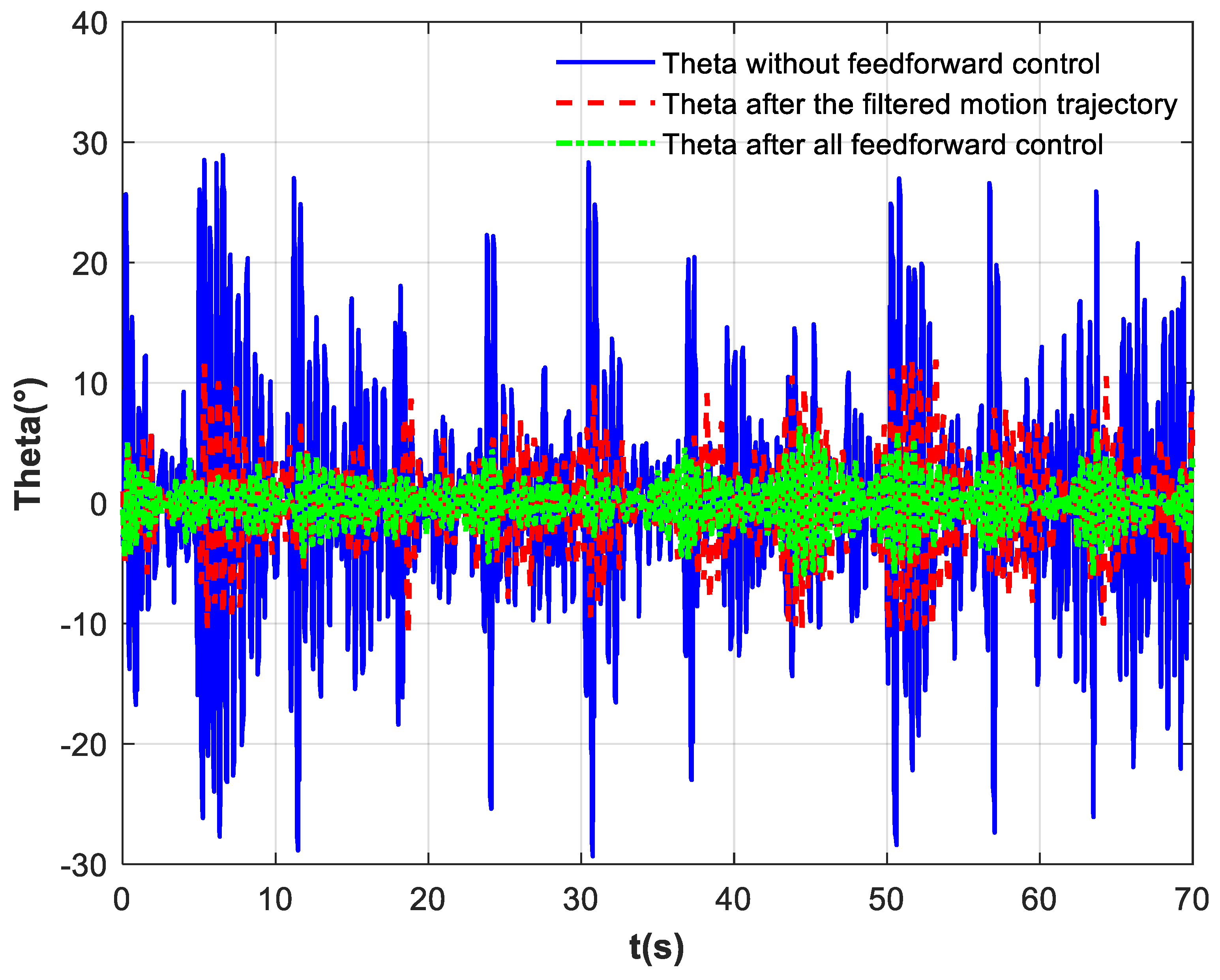

3.3. Sloshing-Suppression-Oriented Enhanced Feedforward-Impedance Control Strategy

To enable the robotic arm to smoothly assist the subject in transporting the water cup while suppressing sloshing of the ball, an exponential filter is applied to the cup–ball system to smooth the robotic arm’s trajectory, thereby mitigating sloshing dynamics. In addition, a feedforward compensation force is introduced based on impedance control to counteract shaking induced by ball acceleration. Accordingly, this study proposes an enhanced sloshing suppression strategy combining feedforward compensation with impedance control, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

The robot employs PD control to provide a stable foundation for low-level feedback, ensuring basic convergence of motion. The exponential filter smooths the reference trajectory of the robotic arm to reduce accelerations that excite sloshing. Based on the dynamic model of the ball, a suitable feedforward compensation force is computed and incorporated into the impedance controller. A six-axis force sensor is employed to measure the interaction force from the patient’s hand. Impedance control ensures compliance in human–robot collaboration. Together, these components enable cooperative human–robot motion that effectively suppresses ball sloshing.

3.3.1. The Exponential Filter

During the robotic arm-assisted movement of the hemispherical cup, the ball inside undergoes oscillations due to inertial forces. The participant must continuously perceive the ball’s motion, predict its dynamic tendency, and adjust their own movement in real time to compensate for the ball’s behavior, thereby preventing it from spilling out of the cup. However, hemiparetic limbs in post-stroke patients are often difficult to control voluntarily. Moreover, movements of the affected limb are frequently accompanied by tremors or sudden jerks—high-frequency noise that transmits through the handle to the cup, exacerbating the sloshing of the ball. Drawing on industrial methods for suppressing liquid sloshing, an appropriate feedforward control action can be applied to attenuate oscillations in such vibratory systems [

33]. Dynamic systems exhibiting oscillatory behavior can be modeled by Equation (12), while the structure of the exponential filter is given in Equation (13). Under the conditions of

,

, residual sloshing can be suppressed.

The Laplace transform is applied to both sides of Equation (11), and the transfer function of the ball–hemispherical cup system is obtained as Equation (14).

The poles of this function are determined by the denominator, as shown in Equation (15). This pair of conjugate complex poles is the inherent vibration mode of sloshing of the ball. Substituting

and T into

, the zero point of the filter is determined by the molecules

. Simplifying yields

. The zero values of the filter and the poles of the system are completely coincident. When the filter is connected in series with the cup–ball system, the zero point of the filter and the poles of the system completely cancel each other out. The sloshing components that would have been amplified/continuously excited by the poles are suppressed/canceled by the zero point of the filter.

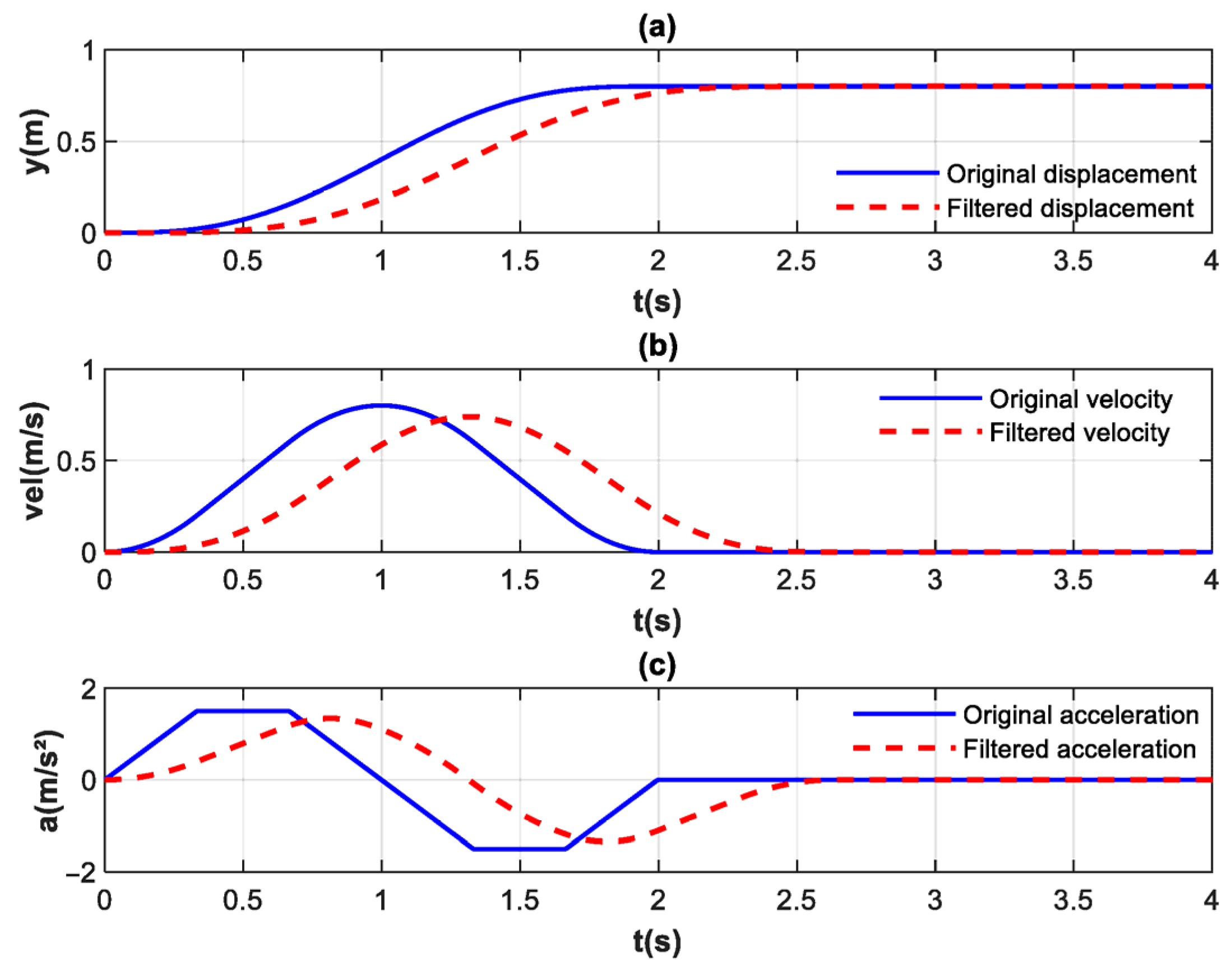

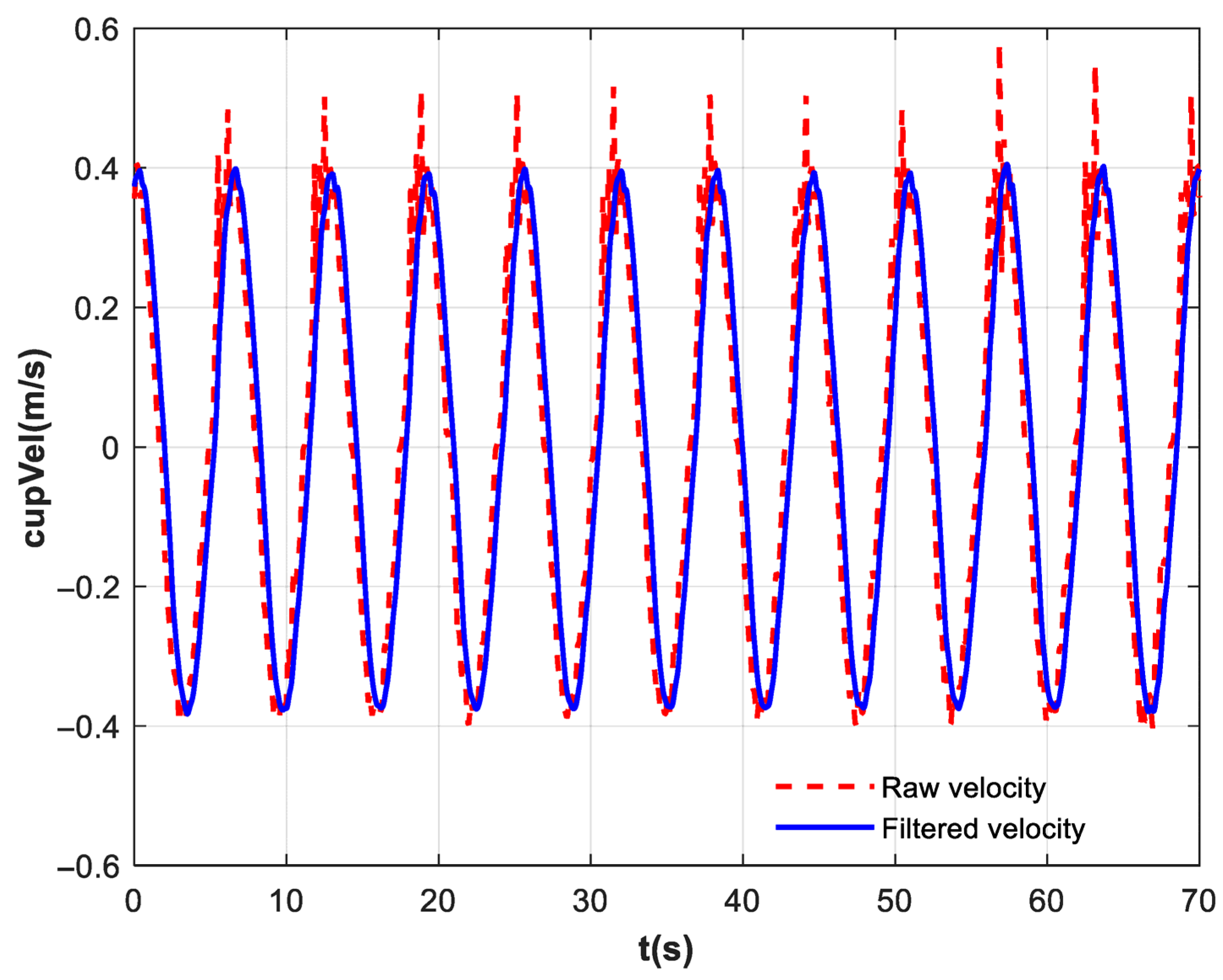

The filtered trajectory is shown in Equation (16).

where

represents the patient’s raw motion trajectory, and

represents the filtered desired trajectory.

In the frequency domain, the filter’s zeros are used to cancel out the poles of the ball–cup system, thereby blocking the energy transfer at the resonant frequency from the source. In the time domain, the trajectory is smoothed through recursive weighted averaging to achieve a balance between noise suppression and dynamic response speed. This eliminates trajectory discontinuities while not delaying trajectory tracking significantly. The digital control of the robotic arm necessitated the discretization of the continuous transfer function. Discretization via the Zero-Order Hold (ZOH) method resulted in a discrete exponential filter in recursive form, as presented in Equation (17).

where

X(

n) denotes the raw trajectory value at the

n-th time step.

Y(

n) represents the filtered trajectory value at the

n-th time step. Based on the foregoing analysis, the exponential filter can perform real-time filtering of the patient’s raw motion trajectory to suppress sloshing of the ball, while providing the patient with perceivable action–stability correlation feedback. This is the core foundation for the subsequent feedforward compensation force and impedance control.

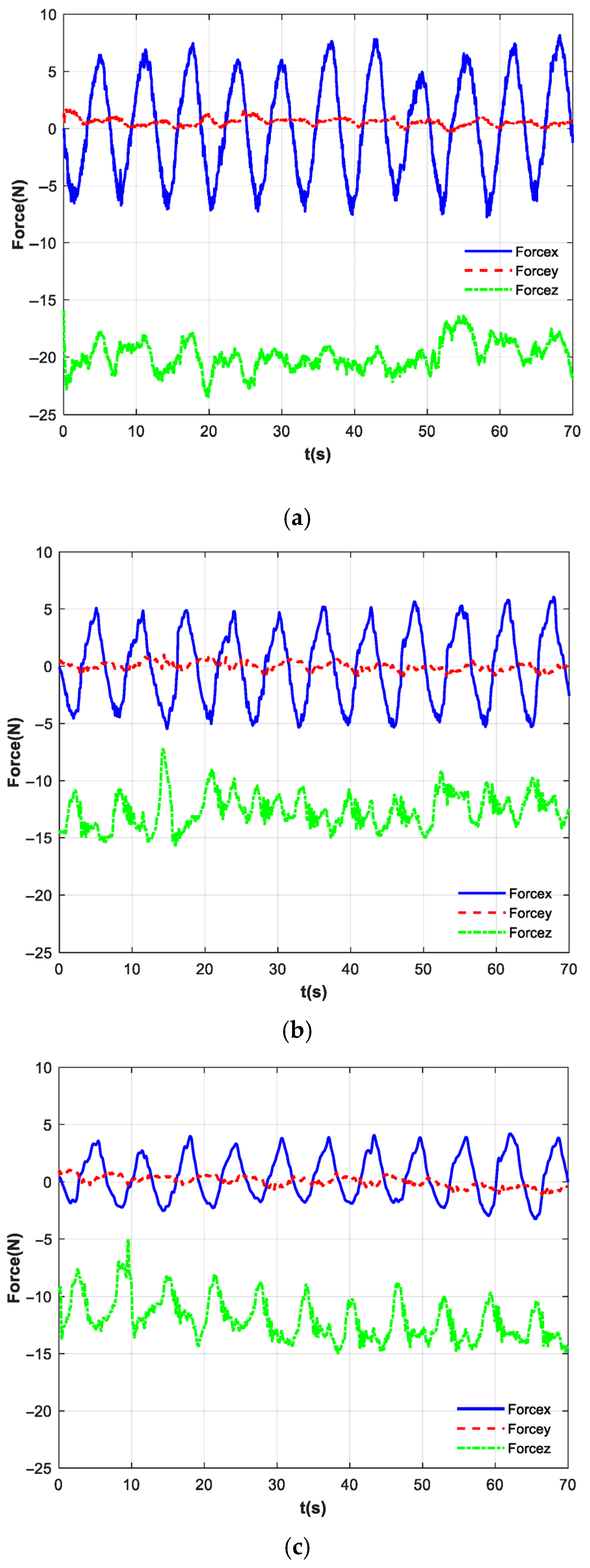

3.3.2. Feedforward Compensation Force and Impedance Control

During robotic-assisted rehabilitation training, the robotic arm is designed to help patients progressively learn to control the cup’s motion to counteract the inertial forces acting on the ball, thereby minimizing sloshing inside the cup. Conventional impedance control in rehabilitation robots typically operates as a feedback strategy, which can only compensate for sloshing after it has been initiated. This reactive approach hinders the establishment of correct movement patterns. Persistent sloshing may degrade the training experience and reduce patient compliance. To address this, the robot can utilize feedforward compensation to allow patients to experience stabilized movement during early training phases. As training progresses, this compensation can be gradually withdrawn to encourage active patient control. By proactively generating a compensation signal that opposes the disturbance, the system can prevent such interference from entering the closed-loop and affecting control performance.

In this study, the feedforward compensation force is derived from the inertial force generated by the ball due to cup motion. Based on the patient’s level of engagement, the robotic arm applies a tailored force to counteract all or part of this inertial force. This approach not only mitigates ball sloshing and prevents spillage but also aids the patient in developing an accurate sense of movement more efficiently.

The raw motion trajectory is processed by exponential filtering to obtain a smooth trajectory, based on which the feedforward compensation force is calculated. The motion of the ball inside the cup is modeled as that of an entrained particle. The force

Fball exerted on the cup is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the constraint force exerted by the cup on the ball. The absolute acceleration of the ball consists of the entrainment acceleration due to the cup’s motion and the relative sloshing acceleration of the ball with respect to the cup. Under the small-angle approximation, the tangential sloshing acceleration of the ball relative to the cup is given by

. Combining with Equation (11), the feedforward compensation force is derived via Newton’s second law, as presented in Equation (18). The robotic arm acquires joint positions and velocities, computes the cup’s position

xc through forward kinematics, and differentiates it to obtain the raw acceleration

ac. An exponential filter is applied to

ac. A vision sensor detects the ball’s tilt angle

θ and

angular velocity in real time, which are substituted into Equation (18) to compute the compensation force

Fcomp. This force is then combined with the impedance force and sent to the robot controller to actuate the arm.

In rehabilitation, full feedforward compensation removes all ball sloshing but also eliminates the feedback that conveys “perception and learning”. Without compensation, excessive sloshing makes the task prohibitively difficult, especially for patients with weak limb control who cannot properly maneuver the cup. Therefore, the magnitude of the feedforward compensation force needs to be dynamically adjusted to retain the “perceptible sloshing component for the patient”, allowing the patient to gradually learn to perceive and control the sloshing with the assistance of the robotic arm. We propose an adjustment strategy based on patient engagement level

α (0 ≤

α ≤ 1), where α is calculated from forces measured by a six-axis force/torque sensor, as shown in Equation (19).

where

nslosh represents the direction vector of the

Fball, ensuring that only the effective component of the human hand’s force along the shake suppression direction is calculated. The denominator corresponds to the theoretical magnitude of the shake force. When

α = 0, full feedforward compensation is adopted. In this case, the patient only needs to follow the movements of the robotic arm for passive training. When

α = 1, the patient is active, and there is no compensatory force. When 0 <

α < 1,

Fcomp cancels out

Fball according to the patient’s requirements, while the remaining portion must be offset by the patient’s active force exertion. This approach ensures that “perceptible sloshing signals” are preserved to help the patient establish control associations, while simultaneously relying on feedforward compensation to prevent loss of sway control.

By dynamically adapting the feedforward compensation force according to the patient’s degree of engagement, this approach achieves a dual objective: it retains the inherent advantage of feedforward control in disturbance rejection, while simultaneously establishing the crucial “progressive perception-to-control” cycle essential for rehabilitation training. This process enables stroke patients to gradually develop the ability to perceive and regulate liquid-like sloshing vibrations—simulated by the ball’s motion—with robotic arm assistance.

In the context of enhancing compliance control in rehabilitation robotic systems, impedance control is widely recognized as one of the simplest and most effective strategies, which can be implemented via position-based or torque-based frameworks. During rehabilitation training, our goal is to progressively reduce the robotic assistance level as the patient’s motor control improves. The control strategy must therefore balance two key objectives: assisting the patient in completing movements and guiding them to learn autonomous oversuppression of overshoot. Therefore, this study proposes an impedance control method integrated with feedforward compensation. Based on the patient’s engagement level and sloshing indicator, the feedforward compensation force is progressively reduced. The impedance control component enables the robot to exhibit compliant dynamics, while the feedforward compensator proactively counteracts known disturbances or anticipated forces.

Impedance control establishes a dynamic relationship between force and position, allowing the robot’s end-effector to demonstrate compliant mechanical behavior during environmental interaction. The feedforward compensation is designed to counteract the reaction force resulting from ball sloshing within the cup–ball system. This approach helps mitigate dynamic errors in the impedance control, while simultaneously improving response speed and tracking accuracy. The feedforward compensation force is directly injected into the force loop of the impedance controller to preemptively neutralize a portion of the disturbance. This allows the impedance control to primarily respond to the intended interaction force, thereby improving the compliance and naturalness of the human–robot interaction. The force balance equation for the impedance control in Cartesian space is given by Equation (20).

where

xd and

xe represent the expected trajectory and the actual end pose of the robotic arm, respectively.

Md,

Bd,

Kd are, respectively, the target inertia matrix, damping matrix, and stiffness matrix, and

Fcmd is the output force of the robotic arm.

Fh is the active force measured by the six-axis force sensor of the patient’s hand.

The

Fcmd calculated by Equation (20) is the force/torque in Cartesian space. It needs to be converted into torque

τ in the robot’s joint space to drive the robot’s movement. This transformation is based on the robot’s dynamics model, as shown in Equation (21).

where

M(

q) is the robot mass matrix, reflecting the inertial properties of the joints;

C is the Coriolis and centrifugal force vector, representing nonlinear forces during motion; g is the gravity vector, used to compensate for the robot’s own weight;

τ is the control torque of each robot joint, which is the final signal output to the joint motors; and

Jr is the robot Jacobian matrix, which facilitates the transformation between Cartesian space forces/moments and joint space torques.