Young Adults and Allergic Rhinitis: A Population Often Overlooked but in Need of Targeted Help

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Recruitment

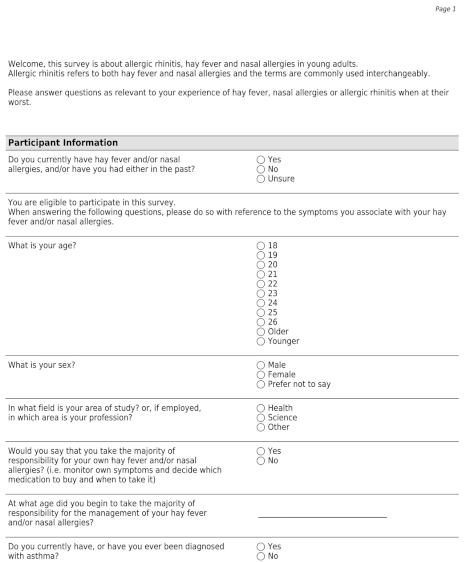

2.2. Survey Development

2.3. Data Collection

- (1)

- Demographics:

- Age

- Gender

- Occupation

- (2)

- AR status:

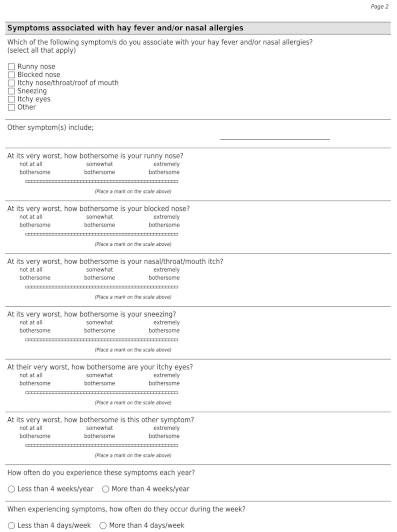

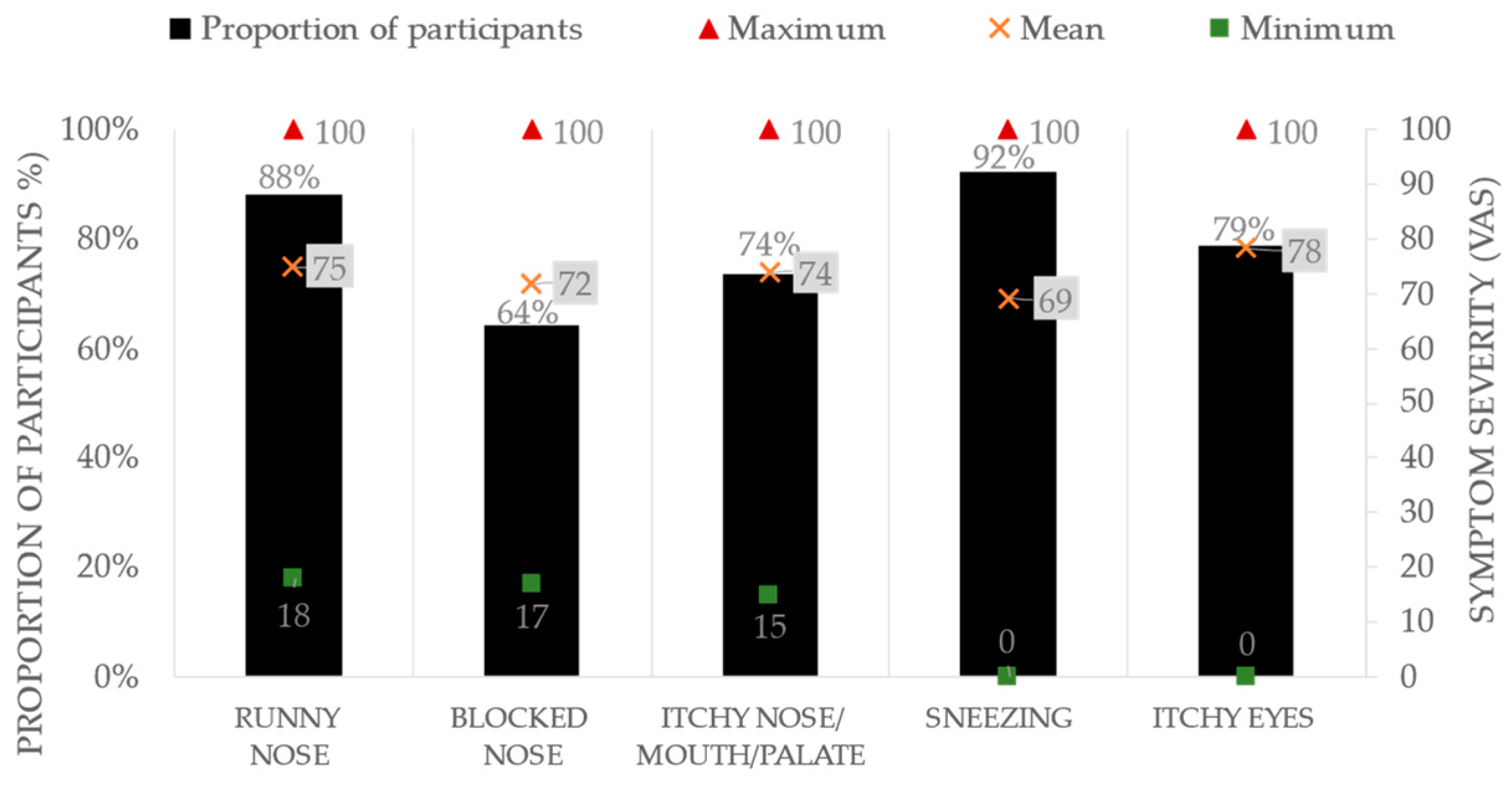

- Frequency and severity of AR symptoms experienced

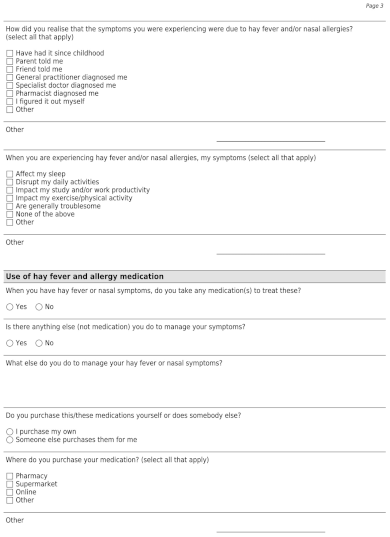

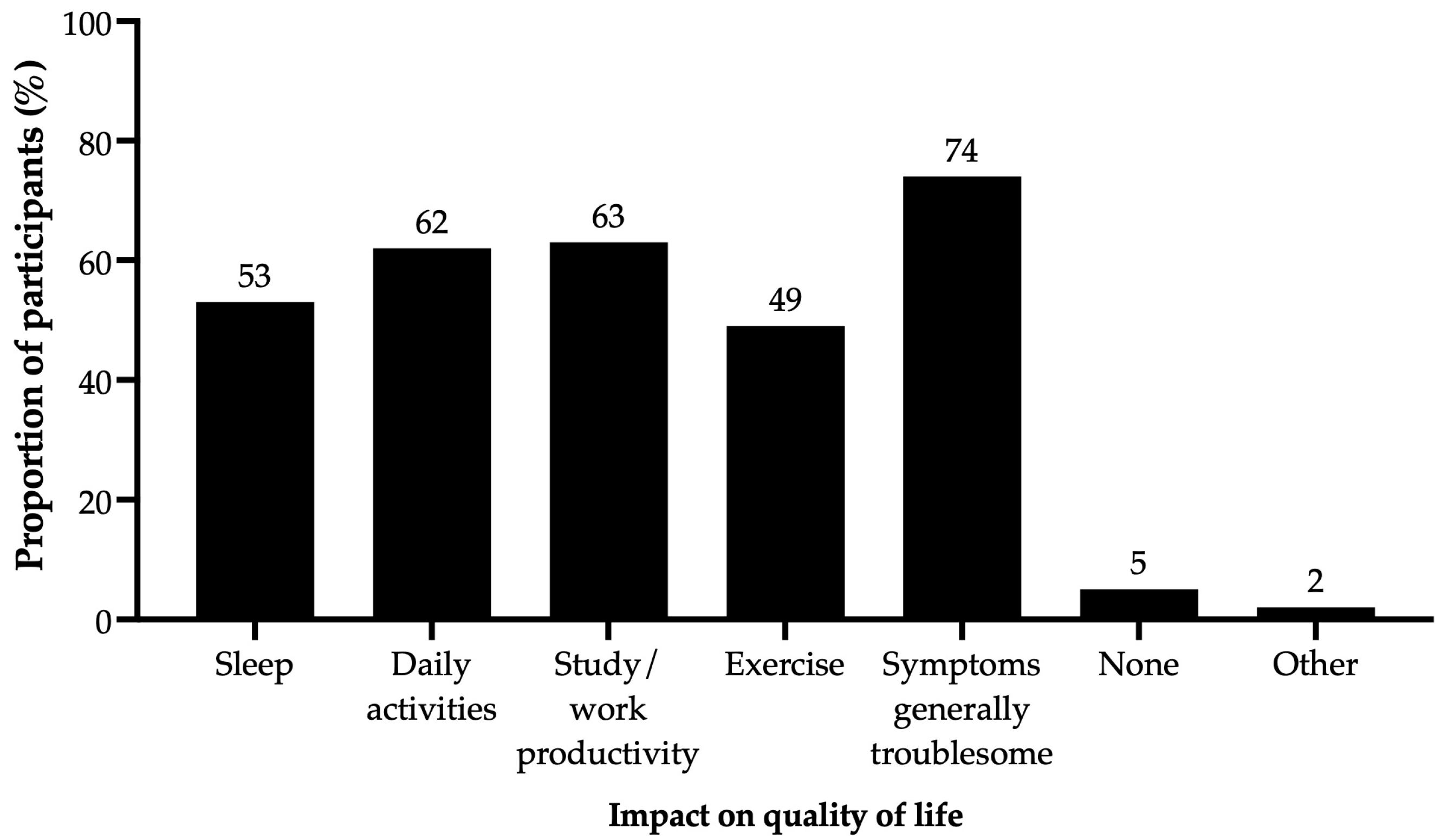

- Burden of AR on quality of life

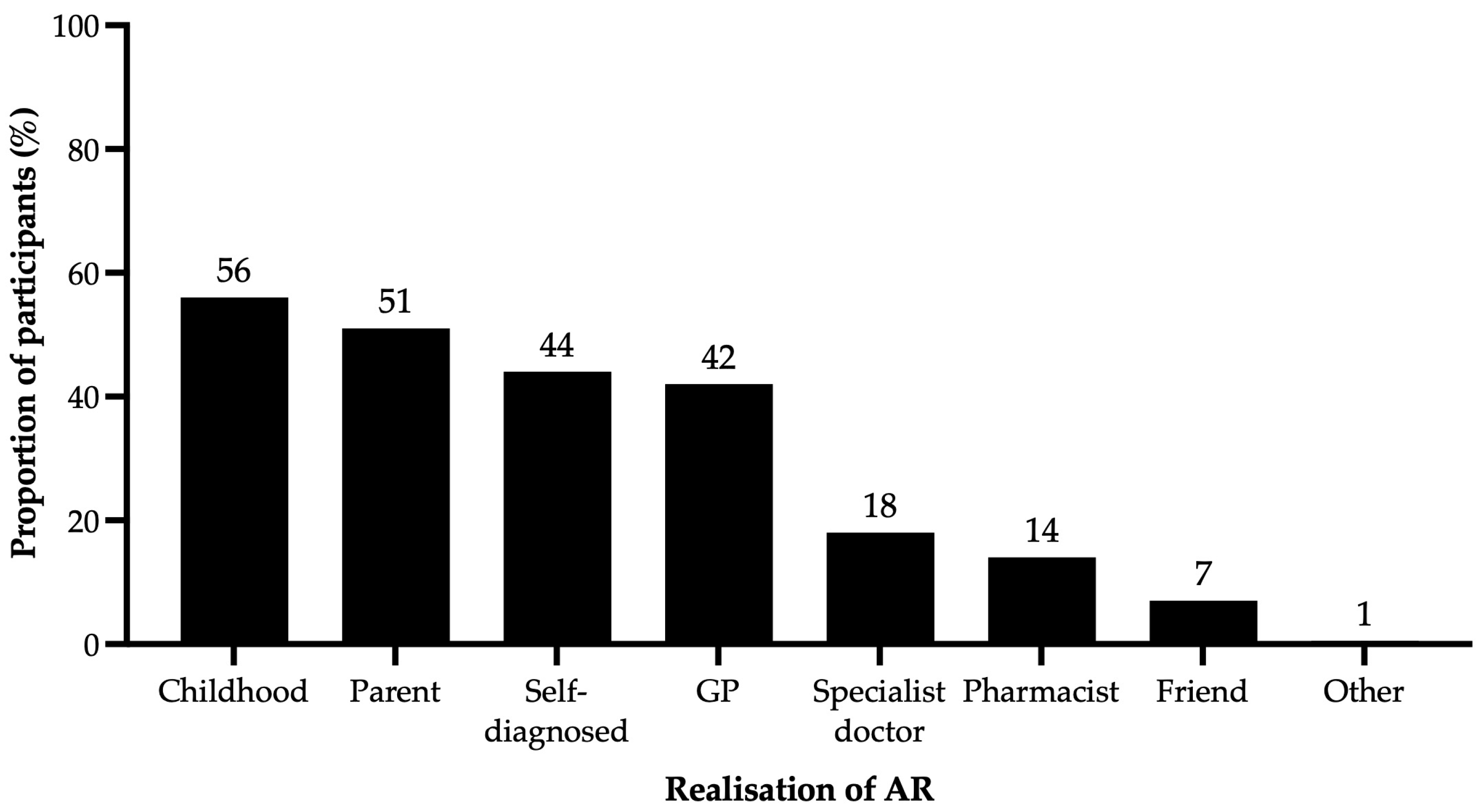

- Diagnosis of AR

- (3)

- AR management:

- Medications and/or non-pharmacological management strategies used to manage AR

- Medication appropriateness

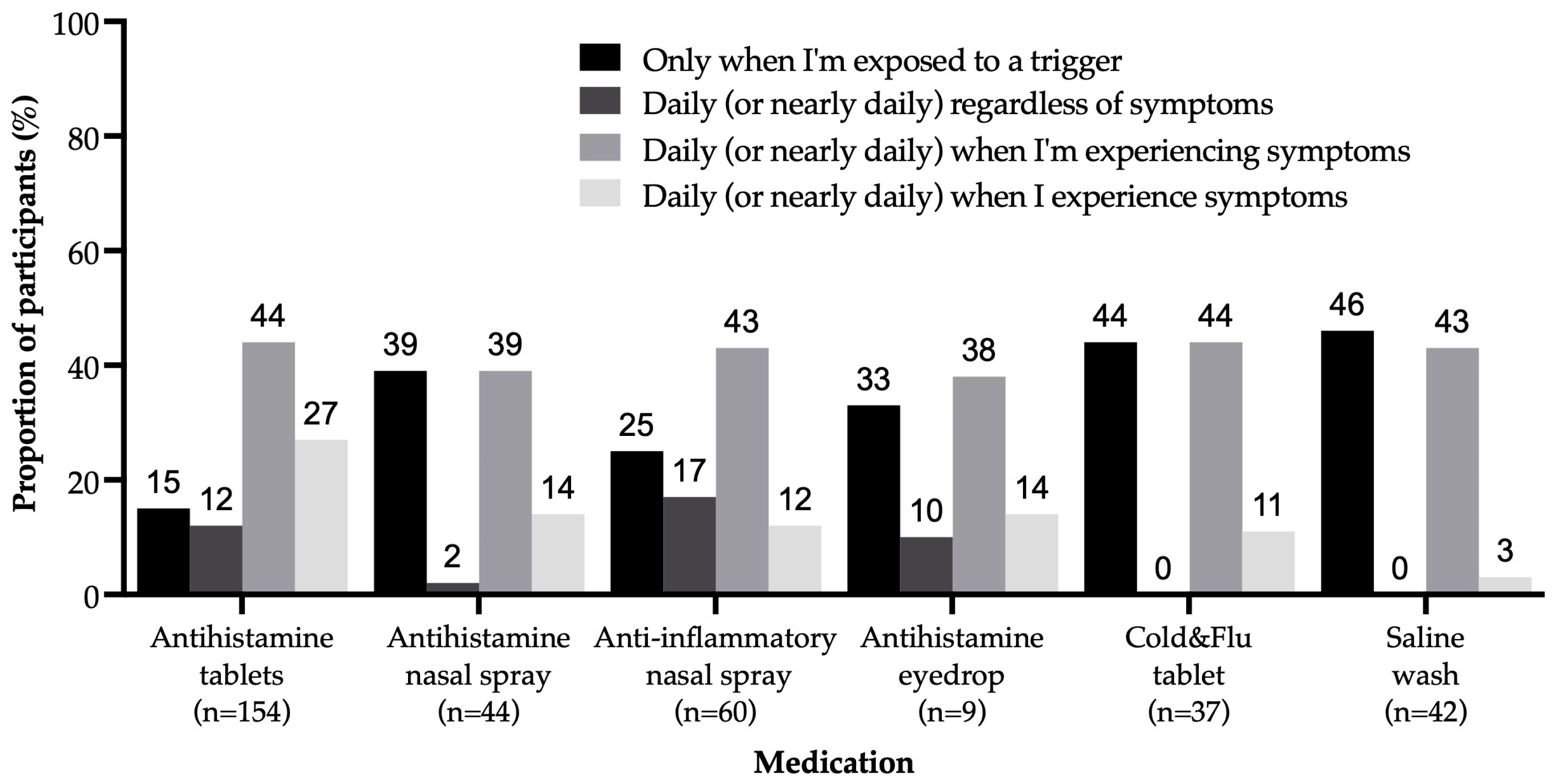

- Medication-taking behaviour

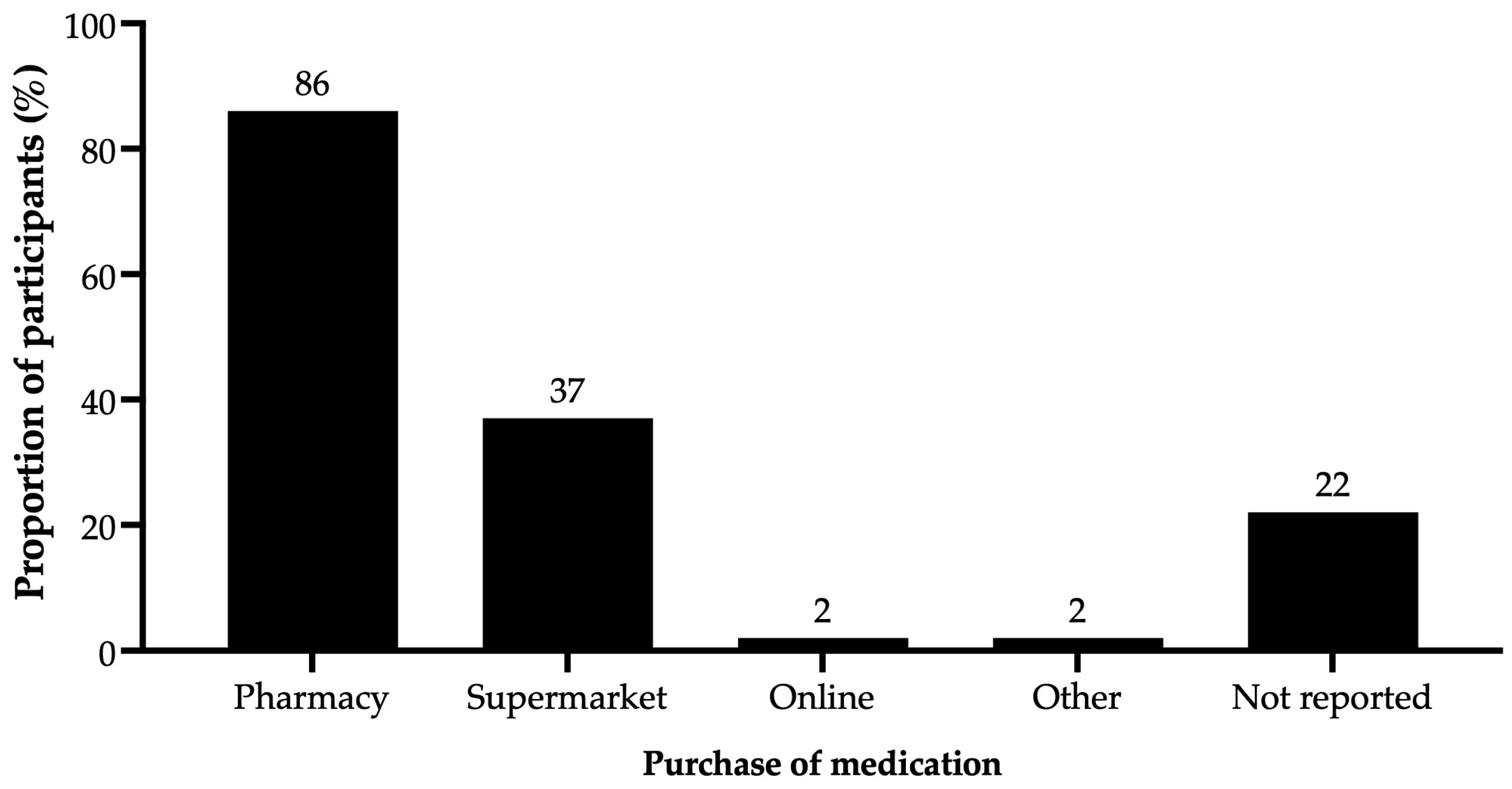

- Medication access

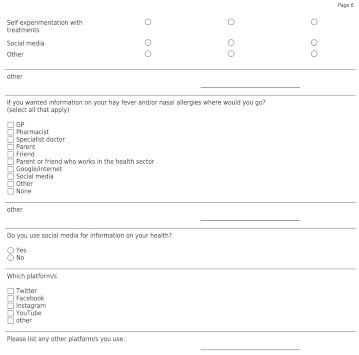

- (4)

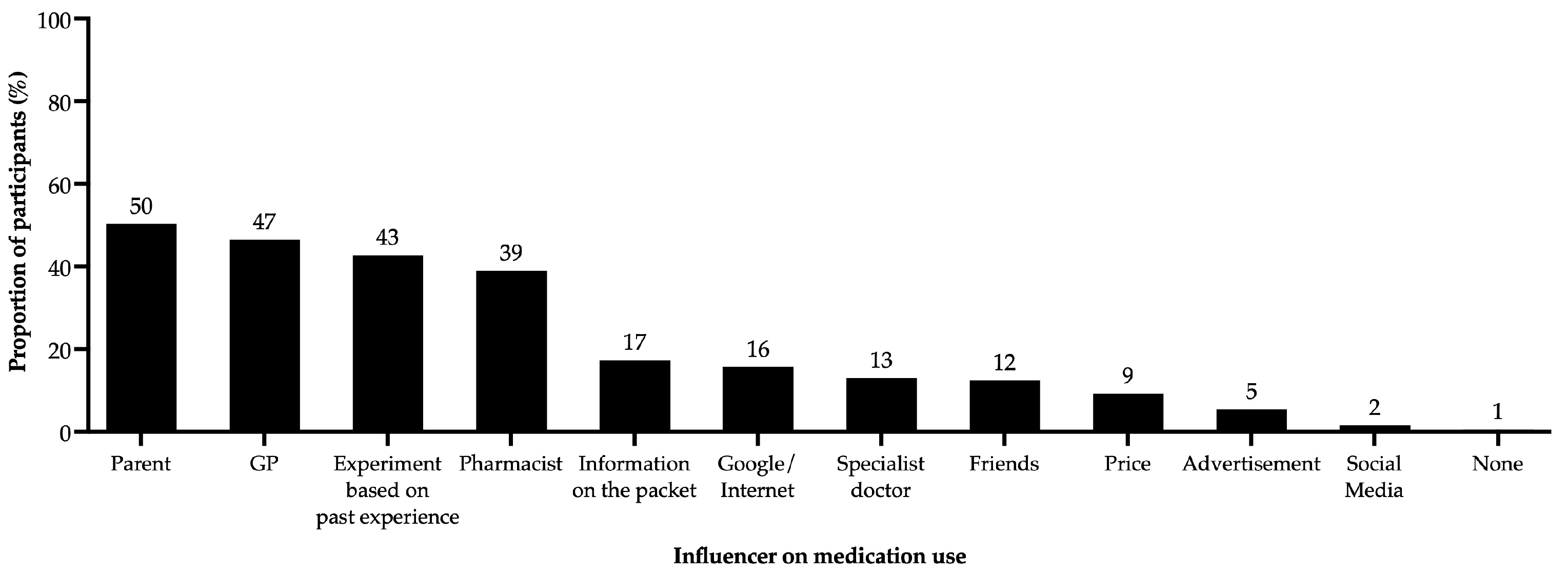

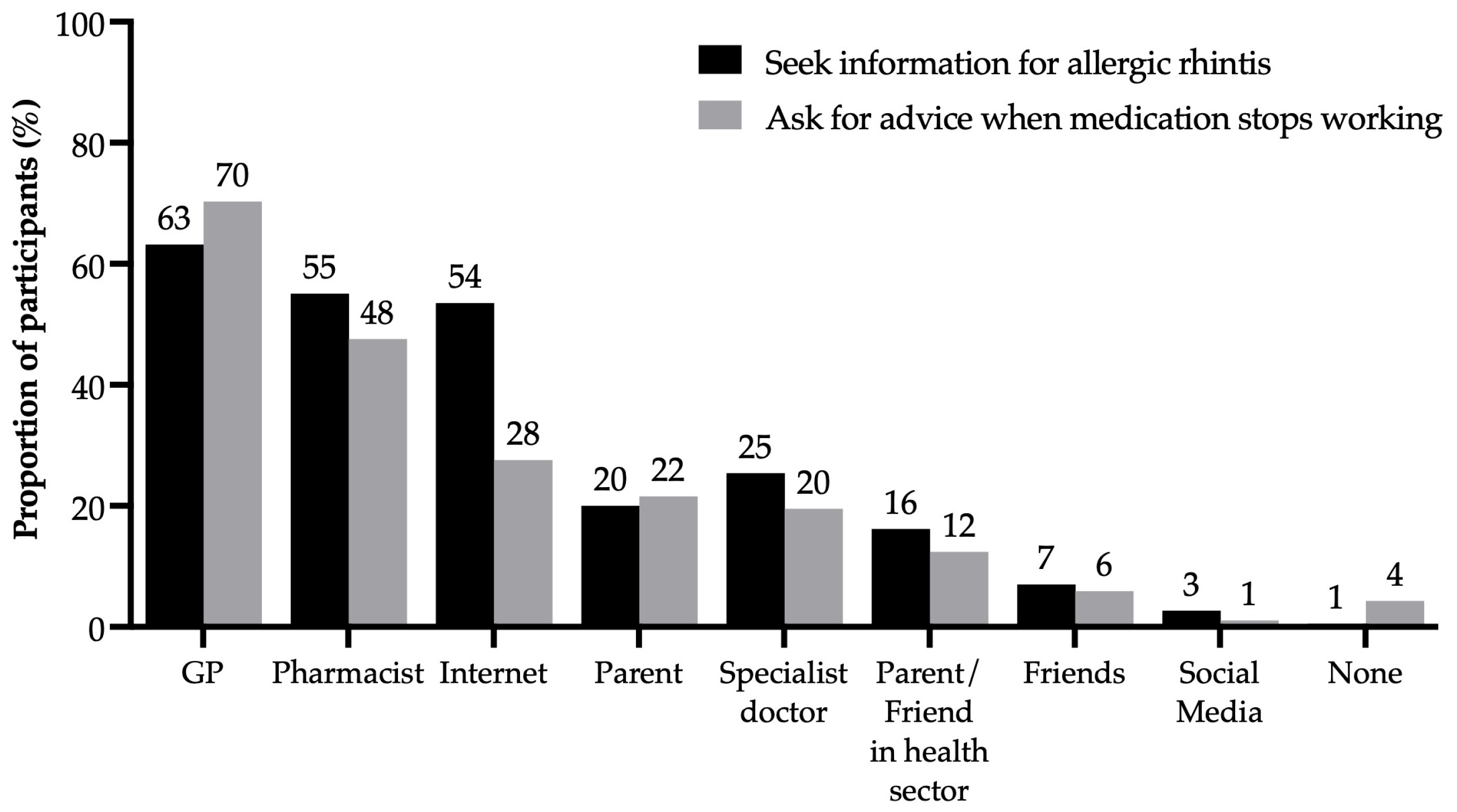

- Influence associated with AR management

- AR networks that include the individuals consulted and resources used to make decisions on AR management

2.4. Data Management

- (1)

- AR status: The AR status for this study was classified into four categories: mild-intermittent, mild-persistent, moderate-severe intermittent, and moderate-severe persistent, based on the severity and frequency of symptoms reported.

- Severity of symptom(s): The severity of symptoms was determined by the degree of burden of each symptom experienced, rated on a visual analogue scale (VAS) in response to the question “At its very worst, how bothersome is this symptom?”, it was determined for this study that <20 mm is mild, 20–49 mm is moderate and ≥50 mm is severe [18]. The highest VAS score recorded among all the symptoms reported was then used to determine the overall AR status as mild or moderate-severe.

- Frequency of symptom(s): The AR symptoms that occurred less than 4 days per week or less than 4 weeks per year were classified as intermittent, and AR symptoms that occurred more than 4 days per week and more than 4 weeks per year were classified as persistent [19]. Although AR can be classified into intermittent and persistent, this classification does not influence the treatment recommended, as treatments are recommended based on the severity of symptoms [18].

- (2)

- Medication appropriateness: The appropriateness of medications used by participants was based on the participant’s AR status and the medications they reported using. The participants’ appropriateness of medication use was determined “optimal” if it was consistent with current guideline recommendations [18]; otherwise, it was deemed “sub-optimal”.

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. AR Status

3.3. AR Management

3.4. Influences Associated with AR Management

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health of Young People; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2024.

- Blaiss, M.S.; Hammerby, E.; Robinson, S.; Kennedy-Martin, T.; Buchs, S. The burden of allergic rhinitis and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis on adolescents: A literature review. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018, 121, 43–52.e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, E.O. Allergic Rhinitis: Burden of Illness, Quality of Life, Comorbidities, and Control. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2016, 36, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.R.; Peters, D.; Calvo, R.A.; Sawyer, S.M.; Foster, J.M.; Smith, L. “Kiss myAsthma”: Using a participatory design approach to develop a self-management app with young people with asthma. J. Asthma 2018, 55, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; White, K. How can health professionals enhance interpersonal communication with adolescents and young adults to improve health care outcomes?: Systematic literature review. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2018, 23, 198–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, A.L.; Green, R. Transition for adolescents and young adults with asthma. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frech, A. Healthy Behavior Trajectories between Adolescence and Young Adulthood. Adv. Life Course Res. 2012, 17, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozer, E.M.; Urquhart, J.T.; Brindis, C.D.; Park, M.J.; Irwin, C.E. Young adult preventive health care guidelines: There but can’t be found. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2012, 166, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Health 2016; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2016.

- Davey, A.; Asprey, A.; Carter, M.; Campbell, J.L. Trust, negotiation, and communication: Young adults’ experiences of primary care services. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013, 14, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetkovski, B.; Tan, R.; Kritikos, V.; Yan, K.; Azzi, E.; Srour, P.; Bosnic-Anticevich, S. A patient-centric analysis to identify key influences in allergic rhinitis management. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2018, 28, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetkovski, B.; Muscat, D.; Bousquet, J.; Cabrera, M.; House, R.; Katsoulotos, G.; Lourenco, O.; Papadopoulos, N.; Price, D.B.; Rimmer, J.; et al. The future of allergic rhinitis management: A partnership between healthcare professionals and patients. World Allergy Organ. J. 2024, 17, 100873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnic-Anticevich, S.; Costa, E.; Menditto, E.; Lourenço, O.; Novellino, E.; Bialek, S.; Briedis, V.; Buonaiuto, R.; Chrystyn, H.; Cvetkovski, B. ARIA pharmacy 2018 “Allergic rhinitis care pathways for community pharmacy” AIRWAYS ICPs initiative (European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing, DG CONNECT and DG Santé) POLLAR (Impact of Air POLLution on Asthma and Rhinitis) GARD Demonstration project. Allergy 2019, 74, 1219–1236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- ASCIA. ASCIA Information for Health Professionals: Allergic Rhinitis Clinical Update. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). Available online: https://www.allergy.org.au/hp/papers/allergic-rhinitis-clinical-update (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Cvetkovski, B.; Kritikos, V.; Tan, R.; Yan, K.; Azzi, E.; Srour, P.; Bosnic-Anticevich, S. A qualitative investigation of the allergic rhinitis network from the perspective of the patient. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2019, 29, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolte, H.; Nepper-Christensen, S.; Backer, V. Unawareness and undertreatment of asthma and allergic rhinitis in a general population. Respir. Med. 2006, 100, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, R.; Cvetkovski, B.; Kritikos, V.; Yan, K.; Price, D.; Smith, P.; Bosnic-Anticevich, S. Management of allergic rhinitis in the community pharmacy: Identifying the reasons behind medication self-selection. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 16, 1332–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, O.; Cvetkovski, B.; Kritikos, V.; House, R.; Scheire, S.; Costa, E.M.; Fonseca, J.A.; Menditto, E.; Bedbrook, A.; Bialek, S. Management of allergic rhinitis symptoms in the pharmacy Pocket guide 2022. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2022, 12, e12183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brożek, J.L.; Bousquet, J.; Agache, I.; Agarwal, A.; Bachert, C.; Bosnic-Anticevich, S.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Canonica, G.W.; Casale, T.; Chavannes, N.H. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines—2016 revision. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, R.; Cvetkovski, B.; Kritikos, V.; Price, D.; Yan, K.; Smith, P.; Bosnic-Anticevich, S. The Burden of Rhinitis and the Impact of Medication Management within the Community Pharmacy Setting. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 1717–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnic-Anticevich, S.; Smith, P.; Abramson, M.; Hespe, C.M.; Johnson, M.; Stosic, R.; Price, D.B. Impact of allergic rhinitis on the day-to-day lives of children: Insights from an Australian cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetkovski, B.; Kritikos, V.; Yan, K.; Bosnic-Anticevich, S. Tell me about your hay fever: A qualitative investigation of allergic rhinitis management from the perspective of the patient. Npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2018, 28, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stull, D.E.; Roberts, L.; Frank, L.; Heithoff, K. Relationship of nasal congestion with sleep, mood, and productivity. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2007, 23, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, E.O.; Bukstein, D.A.; Hamrah, P.M.; Scott, N.; Welz, J.A. Value-Based Perspectives on the Management of Allergic Rhinitis. 2017. Available online: https://www.ahdbonline.com/supplements/value-based-perspectives-on-the-management-of-allergic-rhinitis (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Bruce, E.S.; Lunt, L.; McDonagh, J.E. Sleep in adolescents and young adults. Clin. Med. 2017, 17, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, E.O.; Caballero, F.; Fromer, L.M.; Krouse, J.H.; Scadding, G. Treatment of congestion in upper respiratory diseases. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2010, 3, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takejima, P.M.; Agondi, R.C.; Rodrigues, H.; Aun, M.V.; Kalil, J.; Giavina-Bianchi, P. New Associations Between HLA Genotypes and Asthma Phenotypes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 137, AB104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compalati, E.; Ridolo, E.; Passalacqua, G.; Braido, F.; Villa, E.; Canonica, G.W. The link between allergic rhinitis and asthma: The united airways disease. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2010, 6, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agondi, R.C.; Machado, M.L.; Kalil, J.; Giavina-Bianchi, P. Intranasal corticosteroid administration reduces nonspecific bronchial hyperresponsiveness and improves asthma symptoms. J. Asthma 2008, 45, 754–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demoly, P.; Bossé, I.; Maigret, P. Perception and control of allergic rhinitis in primary care. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2020, 30, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossenbaccus, L.; Linton, S.; Garvey, S.; Ellis, A.K. Towards definitive management of allergic rhinitis: Best use of new and established therapies. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2020, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, M.; Ryan, D.; Angier, E.; Losappio, L.; Flokstra-de Blok, B.M.; Gawlik, R.; Purushotam, D.; Bosnic-Anticevich, S. Current allergy educational needs in primary care. Results of the EAACI working group on primary care survey exploring the confidence to manage and the opportunity to refer patients with allergy. Allergy 2022, 77, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, G.; Vazquez-Ortiz, M.; Knibb, R.; Khaleva, E.; Alviani, C.; Angier, E.; Blumchen, K.; Comberiati, P.; Duca, B.; DunnGalvin, A. EAACI Guidelines on the effective transition of adolescents and young adults with allergy and asthma. Allergy 2020, 75, 2734–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knibb, R.C.; Alviani, C.; Garriga-Baraut, T.; Mortz, C.G.; Vazquez-Ortiz, M.; Angier, E.; Blumchen, K.; Comberiati, P.; Duca, B.; DunnGalvin, A. The effectiveness of interventions to improve self-management for adolescents and young adults with allergic conditions: A systematic review. Allergy 2020, 75, 1881–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, B.G. Motivating patient adherence to allergic rhinitis treatments. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, J.; Anto, J.M.; Bachert, C.; Bosnic-Anticevich, S.; Erhola, M.; Haahtela, T.; Hellings, P.W.; Kuna, P.; Pfaar, O.; Samolinski, B. From ARIA guidelines to the digital transformation of health in rhinitis and asthma multimorbidity. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 54, 1901023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, J.; Khaltaev, N.; Cruz, A.A.; Denburg, J.; Fokkens, W.J.; Togias, A.; Zuberbier, T.; Baena-Cagnani, C.E.; Canonica, G.W.; van Weel, C.; et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA(2)LEN and AllerGen). Allergy 2008, 63 (Suppl. S86), 8–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jones, G.; House, R.; Bosnic-Anticevich, S.; Cheong, L.; Cvetkovski, B. Young Adults and Allergic Rhinitis: A Population Often Overlooked but in Need of Targeted Help. Allergies 2024, 4, 145-161. https://doi.org/10.3390/allergies4040011

Jones G, House R, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Cheong L, Cvetkovski B. Young Adults and Allergic Rhinitis: A Population Often Overlooked but in Need of Targeted Help. Allergies. 2024; 4(4):145-161. https://doi.org/10.3390/allergies4040011

Chicago/Turabian StyleJones, Georgina, Rachel House, Sinthia Bosnic-Anticevich, Lynn Cheong, and Biljana Cvetkovski. 2024. "Young Adults and Allergic Rhinitis: A Population Often Overlooked but in Need of Targeted Help" Allergies 4, no. 4: 145-161. https://doi.org/10.3390/allergies4040011

APA StyleJones, G., House, R., Bosnic-Anticevich, S., Cheong, L., & Cvetkovski, B. (2024). Young Adults and Allergic Rhinitis: A Population Often Overlooked but in Need of Targeted Help. Allergies, 4(4), 145-161. https://doi.org/10.3390/allergies4040011