1. Introduction

The statement “Go West, young man” has often been associated with the overall thrust of migration in United States history. The words are attributed to Horace Greeley, well-known editor of the

New York Tribune, although this may have been a paraphrase of a statement John B. L. Soule made in 1851 (

Taylor 2015). Whatever their source, they express the predominant popular thinking about the overall course of migration in U.S. history. The west as a concept, linked with the American frontier, has occupied a central place in historiography as well as in the imagination (

Turner 1893;

Billington 1956;

Billington and Ridge 2001;

Limerick 1987).

Historically, this east to west pattern tends to have been the case, with migration paths following the expanding frontier. During the colonial period, British immigrants to the North American colonies settled along the Atlantic coastline. Port cities along major interior waterways like New York, Philadelphia, Charleston, and Savannah became critical colonial ports of entry. The “east to west” narrative in many cases masks a more complicated reality often shaped by particular local circumstances, geography, and relations with native peoples, among other causes.

This study examines the settlement of early Dorchester County, located on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. The Eastern Shore, which today includes parts of Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia, known over the course of the last century as the Delmarva peninsula, is a narrow body of land extending from the southeastern region of Maryland and Delaware southwards into the Chesapeake Bay. Two Virginia counties, Accomack and Northampton, form the lower portion of the peninsula and comprise most of the eastern shore area of the bay region. Parts of Somerset, Worcester, and Dorchester counties in Maryland comprise the lower Eastern Shore and the northern boundary of the Chesapeake Bay. On the western side, several smaller peninsulas, punctuated by the Potomac, Rappahannock, York, and James rivers, shape the distinctive geography of one of the world’s largest natural estuaries, one whose watershed spans 64,000 square miles and includes part of six states and the District of Columbia (

Thomas 2004;

Curtin et al. 2001;

Jones 1925;

Torrence 1935).

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, five major groups of Native American peoples lived on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in the area that would become Somerset and Dorchester Counties. The Nanticoke people lived along the Nanticoke River and were among the inhabitants John Smith encountered when he explored the area in 1608. The Choptank people dwelt along the Choptank River in the northern part of Dorchester County and southern Talbot County near present-day Cambridge, Maryland. To the north, near the future boundary between Dorchester, Talbot, and Kent Counties, the Wicomiss people lived in the early seventeenth century. To the south, near what became the boundary between Somerset County and Accomack County, Virginia, lived the Pocomoke people. The Assateague people lived along the Atlantic coast and inhabited some of the coastal islands. Additionally, larger groups often included distinct bands within them, such as the Manokin and Annamessex peoples, both part of the Pocomoke paramountcy. The Manokin people resided in the part of Somerset County that became the town of Princess Anne, and the Annamessex people lived in coastal region that became southwestern Somerset. The Native peoples of the Eastern Shore engaged in fishing, farming, and trade and included Algonquian-speaking peoples, among them the Nanticokes. After the European settlers began to arrive, their numbers declined due to disease, societal disruption, conflict with the European settlers, and relocation. Colonists established Nanticoke reservations along Broad Creek and a Choptank reservation near Cambridge. The names of these Native groups persisted in the place names of the Eastern Shore, however, and, despite their reduced numbers, a notable Native American presence remained in the region throughout the seventeenth century and into the eighteenth century and beyond. By the late 1760s, the Nanticokes had lost their reserved lands to the European-American settlers, but some of the Choptanks retained land into the late eighteenth-century before finally losing rights to it in 1822 (

Rountree and Davidson 1997;

Morfe 2014, revised 2022).

Giovanni de Verrazano, the first European in modern times known to explore the Chesapeake Bay region, visited the area in 1524. Spanish explorers ventured into the region in the middle decades of the sixteenth-century and established a short-lived missionary outpost among the Powhatan peoples. When English colonists off track for New England sailed into the region in 1607, they chose James Fort, later Jamestown, a secluded island located in the lower bay’s James River as their place of settlement. The Powhatan Confederacy, ruled by Chief Powhatan, father of Pocahantas, dominated much of the region, although Powhatan had limited influence on the Eastern Shore, in part because of the Chesapeake Bay and the distance between the Eastern Shore and the rest of what was to become the Virginia colony. John Smith and others visited the Eastern Shore in 1608, and English colonists began carving out plantations in the lower shore region over the following decade (

Perry 1990;

Land 1981;

Billings et al. 1986;

Rountree 1990,

1992,

2005;

Russo and Russo 2012;

Lewis and Loomie 1953;

Gleach 2000).

When English settlers arrived in Maryland in March 1634, they settled on St. Clement’s Island and formed a more permanent settlement shortly afterwards at St. Mary’s City on the isthmus between the Potomac and Patuxent Rivers (

Russo and Russo 2012). Over time, Virginia’s Potomac shoreline would become the boundary between the two colonies, later states. From near Reedville, in present-day Richmond County, Virginia, the line would stretch across the bay to Smith’s Island and from there by water to the mouth of the Pocomoke River, which today forms the boundary between Somerset County, Maryland, and Accomack County, Virginia. From there, the line stretches diagonally about twenty miles to the Chincoteague Bay and the Atlantic Ocean on the region’s eastern shoreline.

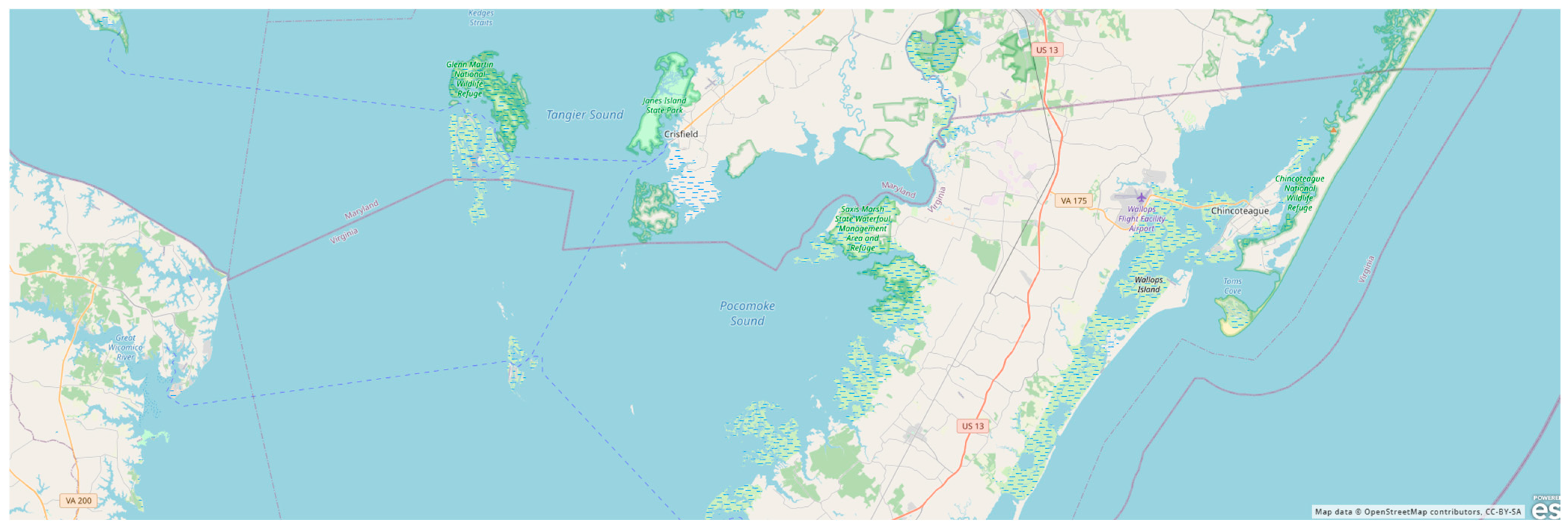

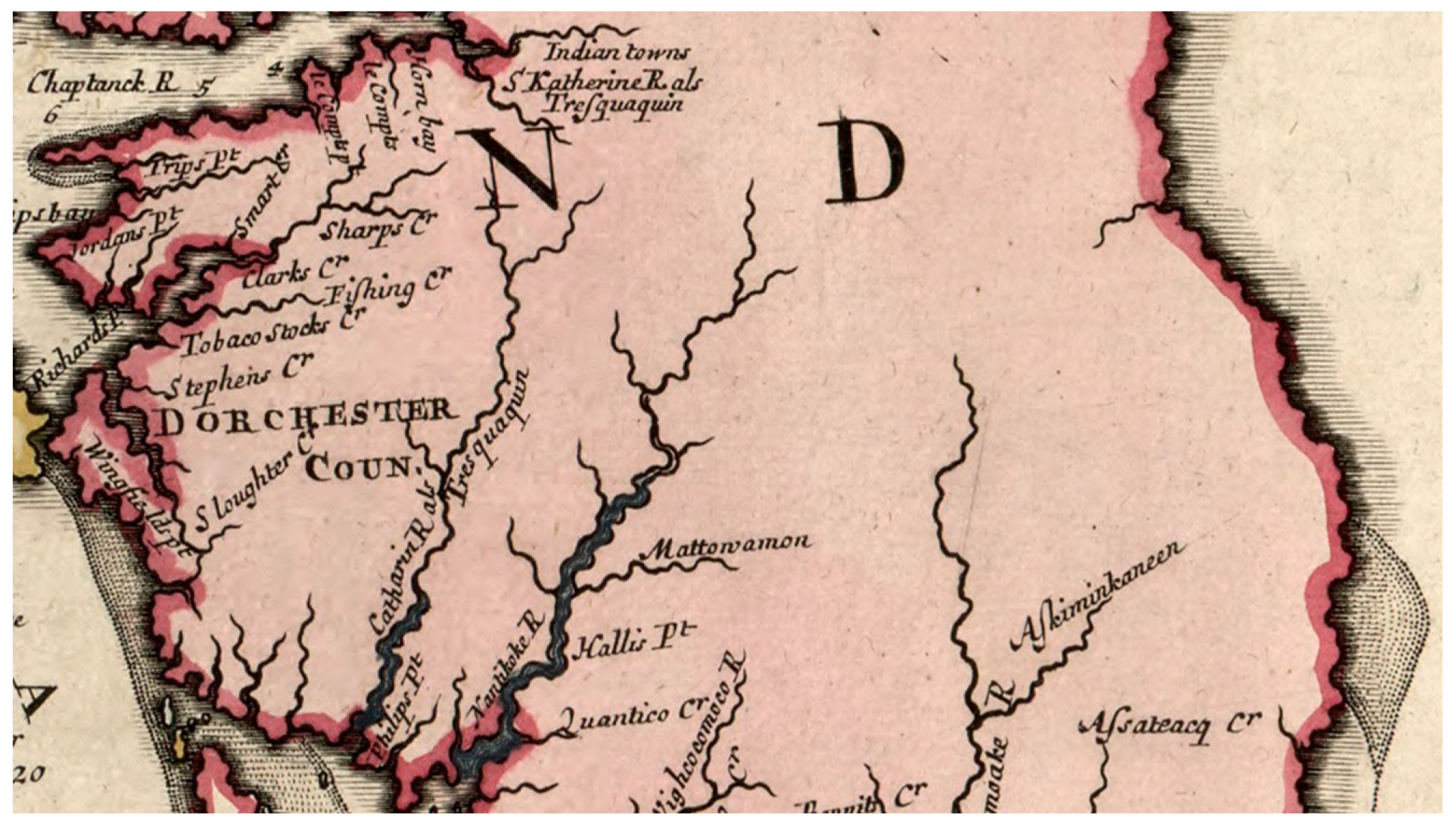

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show this area today, including the modern boundary between Virginia and Maryland.

But, in 1634, these distinctions lay in the future. Boundaries were vague, and colonists would not clarify the boundary between Virginia and Maryland until later in the seventeenth century. They would not settle the boundary between Maryland and southern Delaware until even later. The Catholic settlers who arrived at St. Mary’s in 1634 under the direction of Leonard Calvert came with a different remit than those who had settled at Jamestown in 1607. While predominately English in heritage, religious, cultural, and political differences initially separated them from the Virginia colonists, and rivalries over land and boundaries characterized much of their early relationship (

Russo and Russo 2012;

Danson 2001).

2. Literature Review

I situate this study at the intersection of multiple fields of inquiry: early American history, including the Atlantic context; the regional history of the Chesapeake, including work on the Native American peoples of the region; the state histories of Maryland and Virginia (and, to a lesser extent, Delaware); the local histories of Dorchester, Somerset, Talbot, Accomack, and Northampton Counties on the Eastern Shore; and disciplinary studies of family history, genealogy, demography, migration history, geography, and ecology. The following paragraphs briefly examine key works that provided the intellectual foundation for this study.

The work of E. G. Ravenstein (1834–1913), published in three seminal articles between 1876 and 1889 (

Ravenstein 1876,

1885,

1889), outlined ten laws of migration that have shaped academic study ever since. One of the principles Ravenstein stressed is that migration often occurs in steps with migrants moving a short distance initially followed by a subsequent migration elsewhere (

Conway 1980). Ravenstein also laid the framework for the “push” and “pull” model of migration (

Catapano 2025). Later scholars, including Waldo Tobler and his “First Law of Geography,” built on Ravenstein’s work (

Lawton 1968;

Tobler 1995;

Corbett 2003;

Miller 2004;

Catapano 2025). Ravenstein and Lawton wrote about British migration, and Ravenstein wrote in the second half of the nineteenth century about recent British migration. But the concepts Ravenstein outlined have been applied to migration history more generally in other contexts, often with refinements that consider the effects factors like ethnicity, social class, age, or education may have on the decision to migration or the route or method of migration chosen (

Grigg 1997;

Catapano 2025). In the context of early America, Bernard Bailyn has written extensively about colonial immigration and migration in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (

Bailyn and DeWolfe 1986;

Bailyn 1988,

2005,

2012). Additionally, numerous local studies examine individual settlements and the factors that drew settlers there (

Torrence 1935;

Jones 1925). Frederick Jackson Turner outlined the significance of the western frontier in 1893 with what he termed “the colonization of the Great West,” (

Turner 1893), and the central role of westward migration in American development has been a key concept in historiography (

Billington 1956;

Billington and Ridge 2001;

Hine and Faragher 2000;

Scharff 2002;

McDaniel 2014;

Catapano 2025).

Methodologically, although not primarily a Chesapeake historian, the work of John Putnam Demos has contributed to this study. Two of Demos’s early works,

A Little Commonwealth: Family Life in the Plymouth Colony (1970) and

Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and Culture in Colonial New England (1982) were sophisticated community studies built on the academic study of family history. Demos grounded his study of accused witch Rachel Clinton in a microhistorical analysis of her individual family history, fractured by early death, remarriage, socio-economic change, and mental illness, and its place within local society. He amplified this approach in recreating the social world of the Williams family of Deerfield, Massachusetts, in the late seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries in

The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America. Demos chronicled the life of Eunice Williams, a New England Puritan girl adopted into Mohawk society after being kidnapped during a raid on Deerfield. Given a new name and a new identity as a Native American woman, Eunice never permanently returned to her family in New England despite their ongoing efforts for decades. Demos’s approach to the family and community history continued in later works (

Demos 2004,

2020) and has influenced scholars including Ellen Fitzpatrick (

Fitzpatrick 1983), Rebecca Tannenbaum (

Tannenbaum 1997), Jill Lepore (

Lepore 2001), Wendy Warren (

Warren 2007), Brian Luskey (

Luskey 2016), and others. While this article considers a large group of migrants who lived in a county that spanned nearly 700 square miles, I have modeled my approach to family history, social networks, and community relationships after the microhistorical analysis Demos employs.

In looking at migration into and within the Chesapeake region, the works of Phillip Curtin, Grace Brush, George Fisher, and William Thomas (

Curtin et al. 2001;

Thomas 2004) have been important in outlining the features of the Chesapeake ecosystem and in discussing the relationship between geography, environment, and human activity. The essays in

Discovering the Chesapeake look at the geological heritage of the Chesapeake Bay, its climate, its ecosystem, and how humans have impacted it. Neither Curtin, Brush, Fisher and their fellow authors nor Thomas looked specifically at migration, although the essays in

Discovering the Chesapeake, including contributions by historians such as Lorena S. Walsh, Warren R. Hofstra, Carville Earle, Ronald Hoffman, Anne Yentsch, and William Cronon, address the colonial environment, colonial Chesapeake forests, colonial agriculture, agrarian reform, and the ways humans interacted with the Chesapeake environment more generally. Cronon’s own contribution to the volume builds on his pathbreaking study

Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (

Cronon 1983). Migration is implicit in these works and also plays a role in such studies as those by Edmund Morgan, Lois Green Carr, Jean and J. Elliott Russo, Debra Meyers and Melanie Perrault, and others, although usually as a background factor rather than as a primary focus (

Morgan 1975;

Tate and Ammerman 1979;

Carr et al. 1988,

1991;

Russo and Russo 2012;

Meyers 1997,

2003;

Meyers and Perreault 2006,

2014;

Land 1981;

Land et al. 1977;

Billings et al. 1986;

Rutman and Rutman 1984a,

1984b). Although this study focuses primarily on Maryland, in addition to works just cited, other studies of seventeenth-century Virginia, and the colonial Chesapeake more generally, have also been relevant in terms of the political, social, and economic configuration of the Chesapeake region (

Billings 1991,

2004,

2007,

2010,

2011,

2021;

Billings and Tarter 2017;

Heinemann et al. 2007;

Parent 2003,

2025).

Within the field of early American history, David Hackett Fischer’s

Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (

Fischer 1989) synthesized the vast historiography of early America to argue that colonists transplanted four distinctive regional British folkways to different regions of early America. Settlers from East Anglia transplanted one regional culture to New England. Settlers from southeastern England transplanted a different regional culture to the Chesapeake. Settlers from the western Midlands transplanted a third regional culture to Pennsylvania. And settlers from the British borderlands, including northern Ireland, Scotland, and northern England, transplanted a fourth, and very different, regional culture to the Backcountry region spanning the Appalachian Mountains from western New Hampshire all the way down to what became northern Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, and Kentucky, as well as the western parts of the original colonies. Fischer’s approach blended history and anthropology by focusing on the importance of folkways that shaped the fabric of daily life, including naming patterns, cooking patterns, clothing and dress, religious beliefs, political beliefs, attitudes to the elderly, childrearing customs, architectural patterns. These he attributed to the persistence of ancient regional influences deriving from the ancient kingdoms that came together to form England and, eventually, modern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, fused together into a

United Kingdom through acts in 1284, 1536, 1707, and 1801. Additionally, Fischer incorporated insights from demography throughout his overall approach. Beyond qualitative cultural analysis, he grounded the work in statistical analysis informed by the methodology of New Social History in the 1970s and 1980s (

Fischer 1989). In the thirty-five years since its publication, Fischer’s work has drawn criticism from many fronts, including its skewed portrayal of the British borderlands region and its failure to incorporate non-British cultures into the story of early American life. Additionally, the work altogether failed to incorporate the considerable influence of African American peoples on regional development, particularly in the Chesapeake colonies where they comprised a significant component of the population. But the theoretical framework Fischer constructed, blending history and anthropology, remains a powerful analytical construct.

Fischer’s work represented a vast synthesis of the historiography of early America that has added to the work’s own persistence within historiography. The New Social historians of the 1970s and 1980s had produced scores of county and community studies important methodologically as well as for what they revealed about the fabric of local life in places like Salem, Massachusetts (

Boyer and Nissenbaum 1974), Dedham, Massachusetts (

Lockridge 1970), the Eastern Shore (

Breen and Innes [1980] 2005), and the seventeenth century Chesapeake (

Morgan 1975). In their study, Boyer and Nissenbaum revealed the socio-economic tensions that could fracture local society at Salem, and at Dedham Kenneth Lockridge showed how geography, climate, longevity, and inheritance customs could shape generational tensions within a local community. Breen and Innis examined how a period of socio-cultural fluidity that included intermarriage, collaboration, and exchange between peoples of African and English descent would later give way to a more restrictive, hegemonic society that disenfranchised many of those same families. Edmund Morgan chronicled the larger transformation of Virginia, and to an extent the Chesapeake World more generally, from a society dependent on vast numbers of white indentured servants into a hegemonic, plantation-based, slave-holding society (

Morgan 1975).

Numerous state and local studies both shaped and were shaped by these and other similar studies. Aubrey Land (

Land 1981) provided a narrative history of Maryland’s colonial development that incorporated recent scholarship, as did Billings et al. for colonial Virginia (

Billings et al. 1986). Ongoing work by these authors and other scholars like Emory Evans, Kathleen Brown, James Horne, James Axtell, Frederic Gleach, and many others in the 1990s and early 2000s further shaped the understanding of life in the colonial Tidewater region (

Brown 1996;

Evans 2009;

Axtell 1985,

1988,

1992,

1997,

2000;

Horn 1995;

Gleach 2000). Considering Maryland in particular, the works of the “Hall of Records Gang”—including Lorena S. Walsh, Lois Green Carr, Cary Carson, and others—refined the understanding of life not only in colonial Maryland but throughout the Chesapeake more generally. Rich primary source analysis based on land patents, deeds, probate inventories, wills, court minutes, and documents located abroad in archives in the U.K. grounded these works. In the past twenty years, the widespread availability of primary source material digitized by the Maryland Archives (formerly the Maryland Hall of Records), the Library of Virginia (formerly the Virginia State Library and Archives), Familysearch.org, Ancestry.com, and entities based in the United Kingdom, such as The National Archives, Findmypast.org, and the Society of Genealogists, have transformed the ability to research daily life in the Chesapeake as well as the history of the early colonists who settled there. In particular, by expanding the original print series

Archives of Maryland to

Archives of Maryland Online, the Maryland Archives has made available 865 digitized volumes of transcribed and indexed records relating to Maryland’s history. Beyond this, they also provide access to scores of other digitized, not-yet-transcribed materials, including deeds, probate records, land grant records, and rent rolls. Additionally,

Maryland Land Records, an online database operated through the Maryland Archives, offers digitized copies of the land records from Maryland’s twenty-four county clerks, including the majority of surviving recorded colonial deeds (

Archives of Maryland Online 1999–2025).

Adding to this, researchers on the Eastern Shore have worked extensively to preserve and make accessible records pertaining to the history of that region. Clayton Torrence, Susie M. Ames, and Ralph T. Whitelaw produced studies of Somerset, Accomack, and Northampton Counties still widely used today (

Torrence 1935;

Ames 1954,

1973;

Whitelaw 1951). J. E. Russo’s published Somerset County tax records (

Russo 1992), in addition to the digitized material now available through the Maryland Archives, provides a wealth of demographic data about early residents of the colonial Eastern Shore. More recent works by Howard Mackey and Marlene Groves (

Mackey et al. 1999–2006) have also produced thorough transcriptions of early Eastern Shore records that go beyond the earlier studies of Ames and Whitelaw. Additionally, local history groups throughout the Eastern Shore have worked diligently to gather and preserve material relating to the region’s past. In recent years, this has taken the form of online websites such as M.K. Miles’s database, MilesFiles 23.0 (

Miles 2025), made available through the Eastern Shore Regional Library System’s Eastern Shore of Virginia Heritage Center, and Marshall’s

Early Colonial Settlers of Southern Maryland and Virginia’s Northern Neck Counties (

Marshall 2025). While not academic in nature, user contributed websites like

Genealogy and History of the Eastern Shore (

GHOTES 2025) and the USGenWeb Project county sites and USGenWeb Archives sites for Eastern Shore counties (

MdGenWeb 2025;

USGenWeb 2025) contain maps, records indexes, digital images, and document transcriptions that can serve as a basis for further research. Additionally, the work of the Edward H. Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture at Salisbury University has centralized research materials for the Eastern Shore and produced a number of publications and digital collections (

Nabb 2025). These include the works of former director G. Ray Thompson about early Somerset Co., MD, probate inventories, among them the excellent volume co-authored with Jennifer Lovellette about women’s probate inventories between 1677 and 1726 (

Lovellette and Thompson 1996;

Thompson 1997,

2004). The Nabb Research Center also sponsored a series of helpful publications by Wilmer O. Lankford (

Lankford 1990–2002) that provide a concise directory of early Somerset County settlers. Additionally, works by Robert W. Barnes, Edward F. Wright, Harry Peden, Vernon Skinner, and others (

Barnes et al. 1996–2025;

Moxey and Skinner 1995;

Skinner 1988–1991,

1992–1994,

2004–2011,

2015,

2016a,

2016b) have produced a host of reliable transcribed and indexed seventeenth- and eighteenth-century documents. Skinner’s extensive work with Maryland probate administrations and inventories as well as with colonial debt books (

Skinner 1988–1991,

1992–1994,

2004–2011,

2015,

2016a,

2016b;

Moxey and Skinner 1995) provides useful information about decedents, the nature and value of their possessions, and family and community connections. The contributions of Wright, Peden, Barnes, and others to the

Colonial Families of the Eastern Shore of Maryland (

Barnes et al. 1996–2025) provide helpful background context concerning many colonial settlers. Along with Wright’s own transcriptions of many Eastern Shore records, they have greatly amplified the arsenal of reliable research materials accessible to those interested in the Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virginia (

Wright 1982,

1986). The published volumes of Eastern Shore genealogies by Wright, Barnes, Peden, and others (

Barnes et al. 1996–2025) are reliable overall and provide extensive materials to serve as a groundwork for other researchers, as do essays on Eastern Shore families published in leading genealogical periodicals such as

The American Genealogist (

Ljungstedt 1936–1937;

Russell 1980,

1985,

1990,

2001;

Hansen 1989,

1991;

Knight 2017;

Hatcher 2021).

Over the past two decades, as a result of these efforts, the amount of transcribed and digitized primary source research materials relating to colonial Maryland and Virginia has increased greatly. Many of the secondary works, including published family histories, have tended to focus on European-American families. This is partly due to limitations in the surviving records, which these past individuals created to preserve and protect their own property and power. It is also partly due to a failure of earlier researchers to seriously study the Native American groups residing in the region when Europeans arrived or the people of African descent who lived there from the earliest settlements onward. Over the past decades, this has changed significantly. Research by Helen Rountree, Thomas Davidson, and others has enriched the study of Native American society on the Eastern Shore (

Rountree and Davidson 1997;

Rountree and Turner 2002;

Rountree 1990,

1992,

1993,

2005). Rountree and Davidson employ archaeological, historical, and ecological research to examine the Native American peoples of the Eastern Shore. Through a chronological approach that traces Native peoples from pre-contact through the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Rountree and Davidson show that significant diversity existed among the Native American societies on the Eastern Shore and argue that these were distinct peoples with unique languages, identities, and customs. Rountree, an expert on the Powhatan Confederacy, and Davidson show that the Native peoples of the Eastern Shore were not simple extensions of the Powhatan Confederacy but, instead, local groupings with their own political structures and societal customs. Their work intersects with scholarship by James Axtell, a pioneer in ethnohistorical research whose scholarship combined history, anthropology, and ethnohistory (

Axtell 1985,

1988). Axtell looked at Native-European interactions across colonial American society, however, while Rountree focuses primarily on the Algonquian-speaking peoples of colonial Virginia and the Powhatan Confederacy in particular (

Axtell 1985,

1988,

1992,

1997,

2000;

Rountree 1990,

1992,

1993,

2005;

Rountree and Turner 2002).

Work by Thomas Davidson and Paul Heinegg on African American families has expanded understanding of the free black population on the Eastern Shore during the colonial period (

Davidson 1991;

Heinegg 2000). Davidson’s contributions to the volume coauthored with Rountree (

Rountree and Davidson 1997) draw from his expertise in this subject. Paul Heinegg’s research documents many African American and mixed-race families of African American descent on the Eastern Shore across several generations. Like Heinegg, Davidson also examines the intersections between the free black community and Native Americans and European American settlers. But, while Heinegg’s work is primarily genealogical in nature, Davidson also examines the social, legal, and economic challenges free African Americans faced.

Following the publication of Morgan’s

American Slavery, American Freedom (

Morgan 1975), Breen and Innis (

Breen and Innes [1980] 2005) first brought the complex nature of racial relations on the Eastern Shore to the attention of historians. Later, Ira Berlin examined what he termed “Atlantic Creoles.” As Berlin defined them, Atlantic Creoles utilized “linguistic dexterity, cultural plasticity, and social agility” to carve out a unique space for them and themselves in colonial society (

Berlin 1996,

1998;

Landers 2011). This group included Eastern Shore figures also discussed by Breen and Innis, such as Emmanuel Driggers and Anthony Johnson. Of African birth or descent, they and other similar individuals often owned property and lived as free people, although their descendants sometimes became enslaved. Heinegg’s work has expanded the focus on many of these individuals and their families across multiple generations, often documenting family relations between people of African descent, people of Native American descent, and people of European descent on the Eastern Shore (

Heinegg 2000).

Importantly, building off earlier work by scholars like Moses Finley and Orlando Patterson, Berlin in his generational and regional analysis of American slavery articulated the distinction between slave societies, those where slavery dominated as the labor system and played a central role in the economic and social systems, and societies with slaves, those where slavery existed as one of multiple labor systems and played a less foundational role in social organization than in slave societies (

Berlin 1998,

2003;

Finley 1980;

Patterson 1982). Anne Yentsch and J. E. Russo have examined the development of slavery on the Eastern Shore, which included both large plantations like those of Edward Lloyd in Talbot County and many individuals who owned few or no slaves (

Yentsch 1994;

Russo 2004). Although slavery was critical, colonial Dorchester was a society with slaves. For most of the seventeenth-century, indentured servitude played a key role in the local economy. Beginning in the middle seventeenth-century, the numbers of enslaved people began to increase in the region, but a considerable and growing free African American population existed alongside large numbers of European American families that owned little or no land and no slaves. Some planters owned many slaves. But Dorchester County and the Eastern Shore more generally had a lower slave population than in the Tidewater regions of Virginia, and the local economy included mixed agriculture and small farming, timber production and shipbuilding, and a significant intercolonial trading network with links to other colonies (

Berlin 1998,

2003;

Yentsch 1994;

Russo 2004;

Clemens 1975,

1980;

Moser 2011;

Ford 2006;

Jones 1925;

Mowbray 1979).

The works of several other scholars have helped frame European-American society on the colonial Eastern Shore in ways that have influenced this essay. In contrast to earlier studies that stressed the chaotic nature of political and social leadership in the colonial Chesapeake, James Perry’s

The Formation of a Society on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, 1615–1665 (

Perry 1990) argued that a more stable, permanent society took shape on the eastern shore early on than had previously been recognized within Virginia historiography. Perry’s approach countered a previous understanding of Chesapeake society that stressed the abrupt cleavages in leadership and authority caused by the early deaths of so many colonists. John Rushton Pagan took this analysis further through his in-depth study of Accomack and Northampton County, Virginia county court records. This appeared first in his 1996 Oxford D.Phil. thesis, “Law and Society in Restoration Virginia” (

Pagan 1996) and later through the much shorter volume derived from that earlier work,

Anne Orthwood’s Bastard: Sex and Law in Early Virginia (

Pagan 2003). Pagan’s work shed light on how colonists transplanted English culture, including thinking about law and law’s relationship to society, to the Chesapeake and transformed it there. In the course, Pagan’s meticulous reconstruction of society in Accomack and Northampton Counties built on Perry’s earlier work and carried the analysis into the later seventeenth century. Together, Perry and Pagan show that a core leadership group took shape early on the Eastern Shore. Despite high mortality and the fact that many leaders had come from outside the traditional ruling groups in England, an evolving leadership group formed whose members, through birth, marriage, remarriage, or family relationships, could often trace their origins to the first or second decade of settlement on the Eastern Shore. And, although legal processes differed from those in England, they protected property, promoted social cohesion, and provided a resource that individuals like Jasper Orthwood, the illegitimate son of an indentured servant, could utilize for their own benefit.

The essay that follows addresses Chesapeake Bay geography and places the Eastern Shore within it before reviewing the four major migration routes into Dorchester. It asks how distinct migration patterns shaped the social, religious, and cultural development of Dorchester County in particular and the Eastern Shore more generally during the colonial period. Through the lens of migration history, it also contributes to study of Eastern Shore society developed by Perry and Pagan by shifting attention northward into southern Maryland and looking at the migration routes that brought settlers there, including individuals who went on to become members of Dorchester’s colonial leadership group. Migration brought some members of other regional elites into Dorchester County. In this fluid society, newcomers, including some from outside the traditional leadership group, were able to achieve social, political, and economic success. They did so at a price, however, that included the exploitation of slaves and white indentured servants as well as the devastation of Native American societies. A concluding section discusses migration, culture, and outmigration from Dorchester. Extensive primary sources available at the county level for the Eastern Shore as well as colony-level land and probate records held by the Maryland Archives greatly facilitated this research. My approach to Chesapeake society on the Eastern Shore has been influenced by the work of Perry and Pagan (

Perry 1990;

Pagan 1996,

2003) and draws in a more general way from an understanding of Chesapeake society developed through the work of Carr, Russo, Curtin, Meyers, Perreault, and others (

Carr et al. 1988;

Russo and Russo 2012;

Curtin et al. 2001;

Meyers and Perreault 2006,

2014). Ravenstein and Catapano (

Ravenstein 1876,

1885,

1889;

Catapano 2025) shape the theoretical framework regarding the causes, methods, and consequences of migration. Work by Fischer and Bailyn on migration and culture in early America provide an overall context for understanding the Chesapeake, and the Eastern Shore in particular, within the British Atlantic World of the early modern period (

Fischer 1989;

Bailyn 1988,

2005,

2012;

Bailyn and DeWolfe 1986). Throughout, the approach to microhistory articulated so eloquently by John Demos and Darrett and Anita Rutman has served as a methodological model (

Demos 1982,

1996,

2000,

2020;

Rabb and Rotberg 1973;

Rutman and Rutman 1984a,

1984b).

Regarding Dorchester County, its early history, and its people, the works of Elias Jones, Calvin and Mary Mowbray, and James A. McAllister have been indispensable (

Jones 1925;

Mowbray 1984;

Mowbray and Mowbray 1992;

McAllister 1962,

2002). Elias Jones wrote an early Dorchester County history that covered the county’s social, economic, and political development. Although not an academic monograph, it provided helpful context on many facets of early Dorchester society. Additionally, publications by Calvin and Mary Mowbray and James McAllister provided critical primary source material that informed this study. Although they attempted no quantification or analysis, Mowbray and Mowbray systematically abstracted early Dorchester land grants in two volumes spanning nearly 400 pages. These abstracts provide key information about the dates of land grants, the prior residences of many migrants, and the locations of the grants themselves. Calvin Mowbray also produced genealogies of many of these families that included abstracts of wills and other legal documents. McAllister’s abstracts of early Dorchester deeds, which span the entire colonial period, document the arrival dates and prior residences of many other early Dorchester settlers not among the original grantees. While some dates remain approximate, together these primary source abstracts provide the core data that informs this study. Interested readers may thus refer to them for further details about the individuals discussed here, their backgrounds and origins, and their land dealings in colonial Dorchester County.

3. Geography

The distinctive Chesapeake geography shaped the region’s settlement and later migration within it after the first settlements had become established locales. The multiple rivers flowing into the Chesapeake Bay provided large interior waterways, and those within Virginia were navigable to the fall line, which marks the boundary between the coastal Tidewater region and the Piedmont. Migration into the region came via the Atlantic Ocean as part of England’s vast commercial network. Once in the bay, ships traversed the coastal waterways, trading with local plantations. In both Virginia and Maryland, a plantation-based economy developed, and major towns were few and far between (

Thomas 2004;

Carr et al. 1988;

Curtin et al. 2001;

Billings 2007).

An understanding of the region’s geography is critical to understanding migration within the Chesapeake Bay region. West to east and south to north migration routes seem counterintuitive to those who study the settlement and development of the lower South and Midwest, where most migration proceeded in a southwesterly direction. The first English settlers sought sheltered locations that afforded protection from weather and the elements, from hostile native Americans, and from other Europeans who might venture into the area. As settlements grew, colonists moved outward in search of land and resources, usually following the same riverways further inland (

Billings 2007;

Rutman and Rutman 1984b;

Billings et al. 1986).

Even within the locales, the riverways shaped local settlement patterns and regional economy. Although he argues for a dynamic system that responded to economic, social, and demographic changes, historical geographer Carville Earle has stressed the primary importance of the ability to navigate riverways, proximity to the Chesapeake Bay, and local soil fertility in determining Chesapeake settlement patterns (

Earle 1975,

1979). Colonists settled near the major rivers, and the marshy, riverine geography of much of the area meant that a society formed that included small scale mixed farming, shipbuilding, and trade as well as plantation-based agriculture. Settlement of the interior moved inward. Large land grants meant that most of eastern Virginia, which had opened for settlement in 1607, nearly thirty years before colonists arrived at St. Mary’s, filled quickly after tobacco cultivation took hold. Even before that, the formation of local hundreds and plantation settlements indicated that colonists quickly moved up the waterways towards the fall line. Native settlements limited where colonists could move, and, in 1622 and 1644, native revolts attempted to repel the white Virginians altogether. (

Billings et al. 1986;

Billings 2007;

Noël Hume 1991;

Clemens 1975,

1980;

Ford 2006;

Moser 2011).

On the Eastern Shore, the narrow isthmus of land extending into the bay and originally known as the “Kingdom of Accomac” attracted colonists. Settlers arrived in the second decade of British colonization, and James Perry has argued that a politically and socially coherent society began to form on the Eastern Shore at an early date. Accomac County, formed in 1634, became Northampton County in 1642. Later, Northampton divided into two counties, with the newer county formed from the northern portion of it named Accomack. The area north of Accomack lay in Maryland, and native peoples lived throughout the region. When British settlers arrived in the middle seventeenth century, they moved inland from the Atlantic and interior Chesapeake Bay coasts. The lower peninsula is, at its widest point, only about twelve miles wide. Further north, at its broadest point, in the area between Salisbury, Maryland, in present-day Wicomico County,

1 and Cambridge in Dorchester County, the peninsula is sixty to seventy miles across. (

Thomas 2004;

Curtin et al. 2001;

Perry 1990;

Pagan 1996;

Torrence 1935).

European-American migrants to colonial Dorchester followed four main routes. One was a north to south migration route that brought settlers into the county from New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and neighboring Talbot County, Maryland. Another was an east to west migration route that brought some settlers into present-day Dorchester County from eastern Maryland and what later became southern Delaware. The distance from the present-day Dorchester boundary to the Atlantic coast is only about thirty-five miles wide, which limited the potential for the traditional east to west migration route. Some migrants traveled into Dorchester from abroad, however, although some of these may have entered Dorchester from the Chesapeake Bay’s interior coastline rather than from the peninsula’s Atlantic coast (

Mowbray 1984;

Mowbray and Mowbray 1992;

McAllister 2002).

The north to south and east to west migration routes were more typical of U.S. migration history, but added to these were two more patterns. One was a west to east migration route that brought settlers from the counties on the west side of the Patuxent River into colonial Dorchester. Another was a south to north migration route that brought settlers from as far as Isle of Wight and Nansemond Counties south of the James River more than one-hundred and fifty miles northward into Dorchester County. In some cases, the two routes intersected, with southern migrants from Virginia traveling first to the west side of the Patuxent River and living there for a number of years before crossing the Patuxent River and Chesapeake Bay into Dorchester County (

Catapano 2025;

Mowbray 1984;

Mowbray and Mowbray 1992;

McAllister 2002).

All of these migrants functioned within an Atlantic migratory culture (

Bailyn and DeWolfe 1986;

Bailyn 1988,

2005;

Games 1999). Many of the early Dorchester settlers had been born across the Atlantic Ocean, in England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, or France. For them, settlement in Dorchester was another phase, often the ultimate one, of a journey that had first begun with migration from rural villages into larger urban areas like London, Bristol, Liverpool, Dublin, or Glasgow (

Bailyn and DeWolfe 1986;

Bailyn 1988;

Games 1999). While the analysis here focuses on four separate patterns, in many cases those patterns became interwoven and overlapping. As part of process of step migration driven by social, cultural, economic, and religious factors, these migrants first settled in one region before moving to another. They existed within an Atlantic framework shaped by ongoing social, cultural, political, and economic change across the seventeenth century, including commercial and religious networks that linked the Chesapeake with New England, the Caribbean, the British Isles, and continental Europe (

Hatfield 2004).

Two examples illustrate this point. The first is the case of Richard Preston, born about 1619 in England. Like others, Preston would most likely have traveled first to a larger English city, where he probably resided for a period of time. He first appeared in Virginia south of the James River in Norfolk County in 1644. As part of the Puritan community in Norfolk County, following the execution of Charles I in 1649, he moved with his family to Calvert County, Maryland. William Stone, a wealthy Puritan merchant who had settled in Virginia before 1622, became Maryland’s governor in 1648. Stone welcomed fellow Puritans into the Maryland colony, and many Virginia Puritans headed north. Preston spent a decade in Calvert County but established himself in Dorchester, which he represented three times in the lower house of the Maryland Assembly, by 1663 (

Troth 1892). A case that highlights the considerable cultural variation within early Dorchester society is that of Antoine LeCompte. LeCompte had been born in “Callis” in France but settled in London during the 1650s. LeCompte may have been affiliated with the Huguenot community that had established itself in the Spitalfields area of eastern London in the seventeenth century. He lived in London during the 1650s and married at St. Helen’s, Bishopsgate, in 1661 to “Esther Dottando of Deepe,” a French woman also living in London.

2 Their likely places of origin were Calais and Dieppe, French coastal towns about eighty miles apart and a similar distance from London itself. The LeComptes first settled in Calvert County on Maryland’s western shore. After a few years, they returned to France. But by 1669, they had relocated to Dorchester County on the Eastern Shore. They spent the rest of their lives there and founded a family that figured prominently in the region’s history (

Culver 1917).

Although these migrants existed within a dynamic Atlantic framework that Bernard Bailyn characterized as “worlds in motion” (

Bailyn 1988), they lived on a simpler scale with each individual decision influencing another. Few, if any, began their journeys with initial goal of settling in Dorchester County. Instead, they followed varied trajectories, often as part of chain movements of related families, from one location to another. The following pages examine each of the four regional migration routes and how and why they brought different streams of settlers to Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

4. Migration from the North

Settlers began patenting lands in Dorchester County in the 1650s, more than a decade before the formation of Dorchester County as a governmental entity in the late 1660s (

Mowbray 1984). They first patented tracts along the Chesapeake Bay shoreline, including the numerous islands located off its coast, and along large interior waterways. Many initial grants were small, but later ones included single tracts of more than two thousand acres. At the time these Europeans began arriving in Dorchester, Native peoples still lived in the area. Although gradual, movement into Dorchester began a process of spatial construction that would transform Native lands into farms, plantations, and commercial centers. Large towns and cities were few in the Chesapeake due to its riverine geography and plantation-based agriculture that meant ships could sail far inland. Cambridge, a small town founded in 1686 that originally functioned as a plantation port, became the county seat. Grants to and settlement by European colonists not only began a process of spatial construction that would transform the world of Native Americans living on the Eastern Shore, but it also initiated a process of territorialization and settler colonialism that aimed to define boundaries and assert sovereignty over the natural landscape. Over time, this led to the reduction of Native peoples and their influence regionally even as it created new spatial relationships and experiences among the settler population. Importantly, while the Native population in Dorchester declined, it was not eliminated, a point discussed further in the concluding sections. As part of the process of remaking the Eastern Shore’s landscape, European settlement pushed Natives to the interior. Treaties afforded them some protection, and lands reserved for them in northeastern Dorchester provided a literal “middle ground” from which the Natives interacted with the local populations in Dorchester, Somerset, and Talbot Counties. While the pages that follow focus largely on the diverse groups of European settlers who arrived in early Dorchester, the routes they took, and their motivations for migration, it is essential to recognize that they did not settle in an unpopulated land or remake a wilderness. Opportunity for them meant not only a lack of the same for Native populations in the region, which had already faced encroachments from Swedish and Dutch settlers to the north, but also a purposeful intent to deprive Native peoples of their lands and cultural autonomy (

Cronon 1991;

White 1991,

2010;

Branch and Stockbruegger 2023;

Wolfe 2006;

Veracini 2024).

Settlers arrived in Dorchester simultaneously from the north, east, west, and south. For analytical purposes, however, the article examines these migration streams separately. One important and culturally distinctive migration route into colonial Dorchester County came from the north. This included migration from northern colonies into Dorchester by way of Delaware as well as migration from more northerly parts of eastern Maryland into Dorchester. Christopher Browne’s 1685 map,

A New Map of Virginia, Maryland, and the Improved Parts of Pennsylvania & New Jersey, showed Dorchester at that time, approximately thirty years after the initial settlements in the area. Development centered along the Chesapeake Bay shore and the riverways that flowed into the interior, and a long swathe of land undeveloped by and uninhabited by Europeans stretched to the north and east. In present-day Delaware, settlement had proceeded primarily into the upper reaches of the Delaware Bay, a coastline shared on the west by present-day Kent County, Delaware, and on the east by the New Jersey shore and the small islands contained there (

Browne 1685).

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Excerpts from Christopher Browne’s 1685 “New Map of Virginia, Maryland, and the Improved Parts of Pennsylvania,” showing Dorchester County and the surrounding Eastern Shore. Source: (

Browne 1685).

A key component of this north to south migration was that it included not only British migrants from outside the predominant settlement patterns within Fischer’s Chesapeake paradigm but also non-British migrants whom Fischer fails to consider altogether. For many of these migrants, a desire to practice their religious faiths freely with other fellow believers, a factor that played little role in Ravenstein’s analysis (

Ravenstein 1876,

1885,

1889), seems to have been a strong motivation to migrate. The case of John Richardson and his family provides an example of migration from this more northerly region through Delaware and then into Dorchester. Richardson seems originally to have settled in New Netherlands. He was mentioned in depositions between 1676 and 1680 as a resident of Dorchester County and may have been living there by 1672.

3 Prior to coming to Dorchester, he had lived at Whorekill in present-day Kent County, Delaware, a settlement dating from 1642 and originally part of the region’s Dutch and Swedish foundation, when it was called

Hoeren-kil or

Hoere-kil. The region fell to the English in 1664, and Kent County was formed in 1681. Richardson may have been Dutch, possibly originally named Ricords or Rickords, although he may also have been of English background. Certainly, his name appears in both Maryland and Delaware on occasion as John Richards, but from the 1670s onwards, after taking up residence in Maryland, the form Richardson seems to have become standard (

Turner 1989;

Cohen 2004;

Standing 1982).

While it is not clear whether Richardson was himself Dutch, other early Dorchester residents were of Dutch origin. The case of Jacob Loockerman offers an example. Loockerman, the only child of Govert Loockerman and Marritje Jans, was born in New Amsterdam in 1652. He had come to Maryland by 1678, when he married a daughter of Irishman Nicholas Keiting, who had settled in Maryland by about 1645 (

Marshall 2025;

Mowbray 1984). Loockerman’s wife Helena exemplified the ethnic and religious diversity of the region as well as the tendency of settlers of diverse backgrounds to mix together. She had first married Bryan O’Daly, another Irishman. Following O’Daly’s death in 1675, she married Loockerman (1652–1730) in 1678. It is unclear whether Keiting and O’Daly were themselves Catholic, but the 1674 will of Roger Shehee included bequests to Bryan O’Daly, Jr., and Constantine O’Keiffe as well as to the Roman Catholic Church. Sheehee seems to have remained in St. Mary’s County, but the Loockermans migrated from this religiously and ethnically mixed community—including associates named De La Roche and le Duc—into Dorchester County about 1679. It is possible that De La Roche or le Duc were Huguenots, followers of John Calvin, like the Loockermans, but it is also possible that they were Catholics like Roger Shehee seems to have been (

Marshall 2025;

Mowbray 1984;

Barnes et al. 1996–2025).

Loockerman’s father Govert Loockerman of New Amsterdam was a prominent merchant there. Jacob Loockerman acquired land in Dorchester at the head of Hungar River in 1682, and he became a commissioner to erect ports and towns in 1683. In the coming years he held prominent political and military positions in Dorchester County and also became a delegate to the colonial Assembly that met in St. Mary’s. Loockerman’s family became a leading one in Dorchester and surrounding counties whose influence lasted throughout the colonial period (

Mowbray 1984). Along with economic opportunity, the relative religious freedom in the colony may have influenced Loockerman’s decision to move south into Maryland. Like the English Puritans whom Governor Stone welcomed in 1649, the Dutch settlers of New Amsterdam followed the teachings of John Calvin. April Hatfield has examined the religious and economic networks that tied together Puritan families like the Allertons of Massachusetts and Virginia’s Northern Neck and Dutch ones like the Varletts, Hacks, and Hermans that moved from New Amsterdam to Accomack Co., VA, in the 1650s. These families remained after the Restoration, and newly settled Dorchester offered not only economic opportunities but a place of relative religious freedom with access to fellow believers (

Hatfield 2004).

In addition to families like the Richardsons and Loockermans that came from further afield, many migrants into northern Dorchester came south from neighboring Talbot County, formed prior to 1661 when a 12 February writ naming its sheriff first mentioned the county. Settlers had already been in the area for several years, and beginning in the 1660s they began to move south from Talbot into northern Dorchester. Many, although by no means all, were Quakers and had ties to the Third Haven Meeting, which met in Talbot County by 1676. Other families in the area included members of the Church of England, and a small Roman Catholic presence on the Eastern Shore led to a chapel of ease built at Doncaster in Talbot County as well as a chapel at Meekins’ Neck in Dorchester, where several local Catholic families from St. Mary’s settled in the 1660s. Still, Dorchester had a relatively small Catholic presence in comparison with other faiths, and a listing in 1706 noted that only seventy-nine Catholics lived in the county at that time (

Jones 1925;

Mowbray 1984;

Third Haven Monthly Meeting 1940).

As compared with the seventy-nine Catholic residents in 1706, the early Dorchester Quakers were at least as numerous and probably more so. The Carson, Edmondson, Fisher, Foster, Fowke, Kennerly, Parrott, Phillips, Pitt, Powell, Taylor, Willis, and Willson families of northern Dorchester are all known to have been Quakers prior to 1700 (

Third Haven Monthly Meeting 1940). They appear in Quaker marriage records and minutes of the Third Haven Monthly meeting. Most had large families, and some held to the faith throughout the colonial period. Among colonial Catholic families in early Dorchester, the Tubmans are perhaps the best known, although some members of the Keene, Dean, Shenton, Staplefort, and Dunnock families were also Catholic (

Jones 1925).

In addition to those mentioned above, many other early Dorchester settlers moved down out of Talbot County.

Table 1 summarizes names of some of them (

Mowbray 1984;

Mowbray and Mowbray 1992). Dates are from land grants, deeds, and other legal documents that may have preceded actual settlement by some years, but they do indicate interest in Dorchester and its lands. Once acquired, new landowners would have begun to develop their own lands for agricultural purposes or to subdivide and rent or sell them to others, a widespread practice.

Families like the Hughes and Powells lived in Dorchester by about the time the county was formed and had already been living in Talbot County for several years. Several of this group seem to have been of Welsh origin, including Richard Hughes, John Pritchett, Margary Price, Robert Roberts, and Thomas and Howell Powell, whom tradition holds descended from the Powell family of Castle Madoc in Powys, Wales (

Mowbray 1984). Howell Powell and his family affiliated with the Quaker faith, as did other Welsh families like the Morris, Lewis, and Morgan families. In some cases, former Puritans also adopted the Quaker faith, as did Richard Preston’s descendants.

Dorchester County is less than one-hundred miles from the present boundary between Maryland and Pennsylvania and only 129 miles from Philadelphia, the epicenter of the Quaker world in colonial British north America. George Fox visited the Dorchester and Talbot County Quakers in 1672, and ties of kinship, marriage, and trade meant that Eastern Shore Quakers retained a distinctive identity throughout the colonial period. Over time, however, the Quaker presence shifted into Talbot County, where membership grew steadily, and the two satellite meetings in Dorchester disappeared by the middle of the eighteenth century (

Carroll 1984). As Fox’s presence on the Eastern Shore in 1672 suggests, however, the Quaker migrants of early Dorchester functioned as part of an extended Atlantic network of fellow believers, much as did the early Dorchester Puritans.

Thus, migration from the north seems to have provided colonial Dorchester with distinctive elements that complicate the regional paradigms outlined by David Hackett Fischer in his classic work

Albion’s Seed. By looking exclusively at settlers from Britain, Fischer failed to consider non-British groups and religious dissenters from Britain that moved into the Chesapeake from the middle colonies or the cultural variation within local societies throughout the larger Atlantic World. Early Dorchester settlers from the north included settlers of Dutch and possibly of Swedish origin as well as several families that had come from Wales, a group Fischer considers only as satellite peoples on the periphery of British migration. The majority of early Dorchester settlers did originate in Britain and the British borderlands region to the north, but early Dorchester society offered opportunities for non-British migrants to thrive. As Jack Greene, Alison Games, and other scholars have argued, the influence of dominant cultures was not always straightforward and hegemonic. Instead of assimilation into the dominant culture, identities tended to be negotiated. Cultural fluidity meant that settlers often spoke multiple languages and moved in and out of identities, combining elements of both rather than abandoning one in favor of another. As shown later, other migration routes into Dorchester brought French Protestants into the region. Early settlers may also have included a small number of Irish Catholics from across the bay in addition to Irish protestants who later came in large numbers. Linguistically, these first- and second-generation migrants would have spoken languages such as Dutch, Gaelic, or French in addition to whatever English they had acquired. Naming patterns and religious folkways would have differed from those of the British colonists as well (

Fischer 1989;

Greene 1993;

Games 1999;

Egerton et al. 2007).

Although some early migrants from the north were Anglican, many seem to have belonged to dissenting faiths that existed outside the framework of the Church of England. A more tolerant society, especially one where land and other economic resources offered the prospect of economic security and even wealth, may have drawn them southward into Dorchester. Over time, just as the number of Quakers in Dorchester dwindled, so too did the visibility of the Calvinists. The Loockermans offer an example of a family that retained elements of their prior identity even as they moved within Dorchester society. Over time, the Loockermans intermarried with other prominent Eastern Shore families, affiliated with the Church of England, and became part of the local governing elite. But the continuation of the given names Jacob, Govert, and Nicholas into the eighteenth-century highlighted their non-British background. Additionally, the family retained the surname Loockerman without Anglicizing it. The 1731 will of Jacob Loockerman, who bequeathed lands to his nephew Govert on the stipulation that they “pass in surname of Loockerman forever,” suggests that, even as the Loockermans may have adopted some behavioral patterns of wealthier English families, this was a deliberate action to retain the family’s non-British identity (

Cotton and Henry 1904–1928).

Perhaps in relation to the growing presence of plantation-based agriculture and slave labor in the eighteenth-century, some of the Dorchester Quakers continued their migration to areas like Philadelphia, urban centers with much larger Quaker populations. An example is the family of Richard Preston, whose grandson Samuel, an influential Quaker merchant, became mayor of Philadelphia in 1711. Others left the faith when they intermarried with non-Quaker families. When they married out of unity, their monthly meetings disowned them. They may not have abandoned their beliefs entirely, but, like the Loockermans, through a process of cultural blending common throughout the Atlantic world, they began to take on blended identities, some of them also moving into the local political and social elite (

Standing 1982;

Mowbray 1984;

Jones 1925;

Mowbray and Mowbray 1992;

Barnes et al. 1996–2025;

Greene 1988,

1993).

5. Migration from the East

A significant and steady stream of migrations into Dorchester County in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries moved westward into southern Dorchester from neighboring Somerset County. Nanticoke Hundred of Somerset County, located on the south side of the Nanticoke River, joined Dorchester County’s eastern boundary. At that time, the interior boundary was somewhat indeterminate but stretched about twenty-five miles from the mouth of the Nanticoke River northeasterly towards the Atlantic Coast. About half of it lay in what is today the state of Delaware, which then included northeastern Dorchester Co., MD, and northern Somerset Co., MD. (For a visual depiction, see: Somerset Hundreds in 1734 (

Lyon 2004,

http://www.mdgenweb.org/somerset/lyonmaps/1734hundreds.htm, accessed 1 August 2025). Colonists made attempts in the later seventeenth century to clarify the colonial boundaries, but not until the surveying of the Mason—Dixon line between 1763 and 1767 did the boundary become fixed (

Danson 2001).

Settlers began to acquire land and move into Dorchester County from Somerset County at an early date. This route of migration never ceased during the colonial period. In colonial Somerset, Nanticoke Hundred, Wicomico Hundred, northern Pocomoke Hundred, northern Bogerternorton Hundred, and almost all of Baltimore Hundred lay east of Dorchester County (which originally included much of present-day Caroline County, formed in 1773), as did the unsettled region between Wicomico and Baltimore Hundreds not developed until the middle of the eighteenth-century. Baltimore Hundred’s eastern boundary spanned Somerset County’s entire Atlantic coastline (

Jones 1925;

Torrence 1935;

Lyon 2004;

Browne 1685).

The migration from Somerset County into Dorchester functioned, for most of these families, as one step in a longer chain that had begun elsewhere. Not settled until the 1660s, Somerset County had many early residents who moved north from the lower Eastern Shore counties of Virginia. Others came directly from England or Ireland as indentured laborers brought into the area in the 1660s, 1670s, and 1680s by merchant planters like William Stevens and David Browne, who patented thousands of acres of land there and sponsored laborers from England, Ireland, and Scotland to work on them. Stevens, one of the wealthiest residents of seventeenth-century Somerset, had been born in Buckinghamshire. David Browne, educated at the University of Glasgow, had several siblings who remained in Scotland. Although Stevens did not share the Presbyterian faith, both men had ties to Francis Makemie and other Presbyterian ministers in Ulster that facilitated the transportation of hundreds of indentured servants into the colony. Ulster Presbyterians belonged to what historians like Alison Games and Bernard Bailyn have termed “transatlantic communities,” particularly in the late seventeenth century, when a steady stream of migrants arrived in the Chesapeake. Experiences on both sides of the ocean shaped such communities, as did the migration experience itself, and they existed in the framework of other overlapping, often competing identities. Ulster Presbyterians faced political, economic, and religious challenges in the 1680s and 1690s, and many opted to leave Ulster for opportunities elsewhere. In addition to Stevens and Browne, ministers like Francis Makemie, Thomas Wilson, William Traile, and Samuel Davis functioned at the nexus of transatlantic networks that reached into local communities throughout Ulster and Lowland Scotland and connected them with the Eastern Shore and greater Atlantic World. Makemie visited the Caribbean, where many Irish servants had settled in the 1650s and 1660s, and lived for extended periods in the Chesapeake. He corresponded with Irish Presbyterians, New England Puritans like Cotton Mather, and political figures in a number of colonies about religious matters. William Traile and Thomas Wilson both preached in Ireland but had close ties to southwestern Scotland, where Traile had lived his early life. They traveled to the Chesapeake followed by members of their congregations. In Maryland and Virginia, they served Presbyterians already settled there as well as new converts from other denominations. Following Makemie’s arrival in Maryland in 1683, ongoing communication with Ulster Presbyterians led hundreds of migrants across the ocean over the next two decades and involved extended communities on both sides of the Atlantic. While some of the followers of Makemie and his fellow ministers paid their own way, many seem to have come as servants to work lands owned by Stevens, Browne, and others (

Torrence 1935;

Sherling 2015;

Bailyn 2005;

Games 2006). By the 1680s and 1690s, many of these servants had completed their indentures and moved into northern Somerset County, where they seem to have rented lands from Stevens, Browne, and men like them. From there, they began to cross the Nanticoke River into southeastern Dorchester County.

Given the direction of this migration stream, most residents of eastern Dorchester County had once lived in or had family and business connections to western Somerset County. Local ferries and bridges connected the two sides of the Nanticoke River, and settlers seem to have crossed routinely for business purposes, religious worship, family gatherings, and community events such as weddings, baptisms, and estate sales. Careful study of Somerset County tax lists suggests that migration back and forth between the two counties occurred frequently. Edward Wheatley, ancestor of the Wheatley family of eastern Dorchester County, began his life in Maryland as an indentured servant in Somerset County in the 1690s. He may have come from Baltimore Hundred near the Atlantic coast, but he eventually lived near the Nanticoke River in the western region of the county. Wheatley died early but left several young children. Dorchester County land and probate records show them intermittently in Dorchester County, where they primarily resided, and Nanticoke Hundred of Somerset County during the 1720s, 1730s, and 1740s. This illustrates the back-and-forth movement between eastern Dorchester and western Somerset, whose boundary—despite it being a substantial geographical divider—seems to have been porous in nature (

Russo 1992;

Barnes et al. 1996–2025;

Jones 1925).

Many early Dorchester families had a background in Somerset County, and migrants continued to enter Dorchester from Somerset throughout the eighteenth century and beyond.

Table 2 provides known examples who entered Dorchester County before 1735 (

Mowbray 1984;

Mowbray and Mowbray 1992).

The examples above illustrate different scenarios that brought families out of Somerset into Dorchester as well as the ongoing nature of the exchange with Somerset County. The first Roger Woolford married Mary Denwood in Somerset. They reared a large family of children there. Roger died in 1702, and his adult children—born between 1663 and 1683—all began moving into southern Dorchester County near the turn of the eighteenth century. James Woolford lived there by 1698, and Roger Woolford, Jr., first acquired land there in 1704. Several daughters married men from Dorchester and settled there. These ties united the Denwood, Woolford, Ennalls, Hicks, Hooper, and Lockerman families into a prominent group that included large property-owners, county officials, military leaders, interpreters and negotiators with Native peoples, and members of the colonial Assembly. They ultimately became one of Dorchester’s most powerful political dynasties in the later colonial period (

Barnes et al. 1996–2025).

At the opposite end of the spectrum were William Wheatley and his brother Joseph Wheatley, sons of the indentured servant Edward Wheatley of Somerset County. The brothers appeared in Somerset County tax records in the early 1730s but had moved across the Nanticoke River into Dorchester County by the middle 1730s. They eventually acquired small tracts of land and established self-sufficient families, although neither brother became wealthy. Dorchester and Somerset County records suggest that while they lived and worked primarily in Dorchester, they had close business and family ties in western Somerset. Joseph Wheatley, for instance, married a daughter of James Phillips, a mariner, who appeared frequently in western Somerset. Phillips himself had moved into Somerset County from Dorchester, where he married the daughter of John Kirk, founder of Cambridge. Her grandfather John Rawlins, an early Dorchester resident, had relocated from the south side of the Patuxent River. The son of an indentured servant, Wheatley never became wealthy, but he had ties through marriage to several prominent Dorchester families. Wheatley died in Dorchester, and his descendants remained there into the nineteenth century. Although Wheatley spent his final years in Dorchester, a series of back-and-forth migrations into and out of Dorchester County from Somerset that complicate Ravenstein’s theory of step migration punctuated his life. His case also shows how a relative newcomer of lower socio-economic status could integrate into an older and better-established family network. Unlike cases where such events facilitated economic advancement, there seems to have been little material benefit for Wheatley or his children. In contrast to Wheatley, however, families like the Woolfords were able to use alliances with the Dorchester establishment for economic and social gain (

Ravenstein 1885,

1889;

Russo 1992;

Barnes et al. 1996–2025;

Archives of Maryland Online 1999–2025).

Linked with migration from Somerset County were two other migration paths that brought settlers into Dorchester. One was an even more westerly migration that drew immigrants across the Atlantic Ocean from England, Ireland, France, and other locations to Dorchester County. Some of these had settled in Somerset County first. Others may have arrived directly into Dorchester County, perhaps traveling into the Chesapeake Bay by boat and arriving in Dorchester from the eastern side of the bay (

Mowbray and Mowbray 1992;

Mowbray 1984;

Barnes et al. 1996–2025). Their journey had begun thousands of miles away, and arrival in Dorchester represented another step in a series of migrations.

It is often difficult to document the origins of colonial colonists since detailed ship manifests do not exist. Many early Dorchester colonists were born in England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, or western Europe, but in most cases their exact points of origin are unknown. Enough documents survive, however, to identify the places of origin of some Dorchester settlers who arrived from abroad. In addition to the Welsh colonists in northern Dorchester already discussed, this group included settlers of varied origin (

Mowbray 1984;

Barnes et al. 1996–2025).

Several early Dorchester settlers are known to have come from England. Early Dorchester landowners Raymond Staplefort and George Thompson, who married Staplefort’s sister, came from England. They had interests in Virginia and Calvert County as well as in Dorchester, where they appeared in legal records during the 1670s. Staplefort’s descendants, including members of the Tubman family, settled permanently in Dorchester. Nicholas and Margaret Goldsborough hailed from Dorsetshire in England, and the Keene brothers who settled in Dorchester were natives of Surrey, near London. Likewise, Thomas Hicks, who married Sarah Denwood, sister of Mary (Denwood) Woolford, was born in England about 1656, probably in Whitehaven, Cumberland, in the far north (

Downing 1916;

Mowbray 1984;

Marshall 2025;

Barnes et al. 1996–2025).

Patrick Mullikane of Dorchester came from Ireland. William Geoghagan, another Irishman, traveled from Dublin. John Henry, an early Presbyterian minister, settled first in Somerset County after leaving Ireland, but he eventually lived in eastern Dorchester. Daniel Sulivane of Dorchester County, who lived there by 1708, seems to have been a native of Ireland. Although much of Ireland still practiced the Catholic faith, the Protestant Presbyterian faith became strong in the north, and most, although perhaps not all, of the early Irish settlers in Dorchester were Presbyterians (

Mowbray 1984;

Marshall 2025;

Barnes et al. 1996–2025).

Several early Dorchester residents came from France. John and Margaret Gootee were French. Anthony LeCompte and wife Esther Dottando, natives of France who emigrated from London, settled first in Calvert County before traveling back to France. Upon their return to Maryland, they had settled in Dorchester by 1669. Milleson Marine, also a Frenchman, had settled initially in Virginia and then moved into Somerset County before settling in Dorchester County about 1670. Additionally, the Collier family of Nanticoke Hundred in Somerset and the Peter Dowdy family there were also Protestants of French origin (

Mowbray 1984;

Marshall 2025;

Barnes et al. 1996–2025).

The French Huguenots and the Scottish and Irish Presbyterians, like the Puritans and Dutch already discussed, adhered to the teachings of the Swiss theologian John Calvin. Hence, an affinity sometimes existed between the two groups that may have influenced settlement patterns on the Eastern Shore. The Presbyterian faith in Dorchester seems to have been particularly strong in the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, probably stemming from the late seventeenth and early eighteenth-century emigration from Scotland and northern Ireland of many Scottish and Ulster Scots Presbyterians. Historian Rankin Sherling has argued that the Presbyterian migration from Ulster to the Eastern Shore was a chain migration. Ulster congregants seem to have followed their ministers across the Atlantic with the result that entire congregations may have relocated over a period of years (

Sherling 2015). This meant that earlier migrants were available to help later ones, a factor that promoted economic stability and social cohesion among the settlers. It also meant that, in contrast to the random nature of most recruited migrations through indentured servitude or forced migrations through enslavement, pre-existing family networks and kinship ties formed in Ireland and Scotland may have persisted on the Eastern Shore. In addition to a large number of Presbyterian settlers from Ulster, Charles Thompson of eastern Dorchester and several brothers emigrated from Scotland and settled in Dorchester County. One brother, Thomas, became a Presbyterian minister, and Dorchester County legal records show that he came from Tulliallan in Perth. These brothers also seem to have emigrated in a linked movement that spanned several years, and the will of Rev. Thomas Thompson indicates that kinship ties between Dorchester and Perth persisted into the eighteenth century (

Jones 1925;

Torrence 1935;

Billings et al. 1986;

Land 1981;

Mowbray 1984;

Barnes et al. 1996–2025).

A substantial number of early Dorchester settlers had Scottish or Irish connections. Many of them had probably been among the Ulster migrants who settled in Somerset County in the late seventeenth-century, and by the early eighteenth-century settlers often called Island Creek in southern Dorchester Ireland Creek (