1. Introduction

Human history, according to

Ilo (

2012), has always been defined by migration caused by diseases, natural disasters, ecological and geographical factors, religious considerations, poverty, and adversities of all kinds. Migration, to him, has always been a way of escaping from a bad condition of life to a better situation, maintaining strongly that “the human person can change and adapt to new situations of life to improve his condition and gain the fullness of life and fulfilment”.

Izuegbu (

2003) posits that in human history, there has always been a central issue of origin and migration, and he says people are naturally anxious and excited when their origins are being discussed. This, therefore, means that the concept of origin and migration is the core of a people’s history such that it is regarded as the pathway leading to and keeping alive what he calls an “otherwise lost past”.

In his

Ubium: History, Customs, and Culture,

Okoko (

1988) stresses that migration comes about as a result of negative factors, such as war, pestilence, family hatred, famine, lack of elbow room in the place of habitation, and so on. Many examples exist demonstrating how communities, fragmented and driven from their original abodes due to slave raids during the over four hundred years of slave trade in Africa, migrated. Perhaps this constitutes why Okoko strongly maintains that “No man who was satisfied and happy where he was, with almost nothing to complain about, could ever think of leaving his home forever to settle in a strange land”. Although “wonder thirst,” which could drive some persons to seek what was new and adventurous and to explore and discover, could not be completely ruled out among pre-colonial people of Africa, Nsit Clan inclusive.

Every group found in Africa or around the world migrated from somewhere; hence, no group is said to be mushrooms that germinate and die on a given spot. Migration in the pre-colonial period was a sort of ‘relay race’ since the same people could not be migrating from one place to another in a shortly. In the words of

Okoko (

1988), originating from Aro-chukwu, a group could establish a settlement, dwelling there for numerous years or generations after covering a convenient distance. The founder, having settled, might remain in that location until their demise, becoming interred there. Subsequently, various factors or motivations might prompt the grand or great-grandchildren of the initial settlers to embark on a quest for a new settlement. Consequently, they would relocate, leaving some relatives behind yet perpetuating the original group’s name. This cyclical process persisted, and over many years and generations, descendants of this family eventually arrived at their current dwellings.

In pre-colonial Africa, nay Ibibio land, when a group of people embarked on a journey or migrated from their original habitation, they would carry a fragment or piece of their God and culture. They would situate their God in their new settlement and continue with their tradition, culture, and rituals as they or their forebears did in their original home. Migrants in pre-colonial African societies commonly adhered to their pre-existing customs, totems, and taboos. However, some migrants assimilated into the culture of their new environment, but despite the new environmental influences, traces of the original culture of the migrants could still be found among them.

The term “Ibibio land”

Urua (

2004)

Akpan (

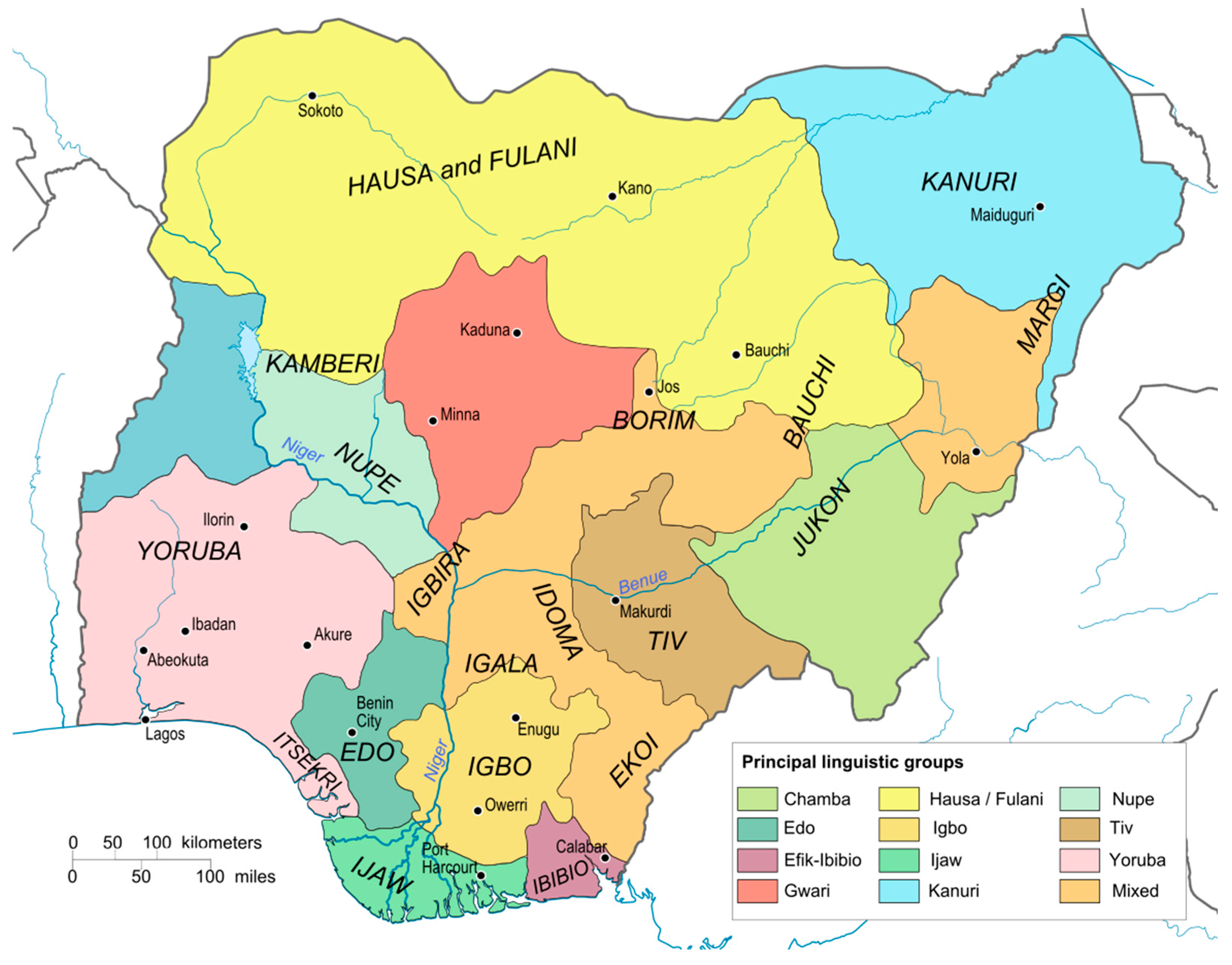

2018) in this context refers to the entire region now known as Akwa Ibom State, encompassing areas such as Western Nsit, as well as the southern portions of Cross River State, including Calabar, Akpabuyo, Akamkpa, Odukpani, and Bakassi. The predominant languages spoken in this territory are Ibibio and its closely related dialect, Efik. The Ibibio people, their linguistic heritage, and geographical setting are distinct from Igbo territory, although they share a border with the Igbo communities of Eastern Nigeria (see

Figure 1).

Therefore, religion, culture, totem taboos, tradition, and customs point to a common origin and relationship among groups. Nevertheless, they can also point to a cultural sphere shared by groups that do not necessarily have a common origin, though they often point to a common origin. These make the study of origin migration and intergroup relations easy for scholars. For example, the Afaha people are found everywhere in Ibibio land. Some Afaha villages do not attach “Afaha” to their names, but the only thing that makes one identify them as Afaha villages is their common totem, “elephant”. The primary totem, according to

Akpan (

2018), signifies a common origin. Totemism is, therefore, a methodological device that has been used by historians interested in African history to reconstruct the history of many societies, especially their origin, migration, and inter-group diplomacy. Erim maintains that totems are a theory of origin and a theory of the relationship of groups of people

Erim (

1998). Aligning with this thought, Akpan admits that “clans or kindred groups that revere the elephant (as the Afaha people do), regardless of their modern geographical spread in the society, were supposed to be related ethnically in the past”.

However, several villages in Western Nsit have oral traditions and ethnographic data that explain their migration histories. For instance, the Oboyo group has the “ukpoppo ukim” legend, which explains how they dispersed from Ita Uruan. Ita Uruan, where they migrated from, also has the same legend. The Afaha group also has the same legend, though, according to

Obio-Offiong (

1958), the ukpoppo ukim incident which is captured in their legend took place at Akwa Akpa near Cameroun during the reign of the Afaha king called Obio Offiong.

The main research questions guiding this study.

This study is guided by several key research questions that explore the history, migration, and cultural dynamics of the Western Nsit Clan in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Central to this inquiry is an examination of the origins and migration patterns of the clan, as well as the environmental, cultural, economic, and external factors that influenced their movement and settlement over time. Additionally, this research investigates the role of religion, totems, and cultural practices in shaping the identity and cohesion of the Western Nsit Clan, offering insights into how these elements contributed to their collective sense of belonging and continuity.

This study addresses significant gaps in the existing literature in multiple ways. First, it provides a comprehensive tracing of the complex historical trajectory of the Western Nsit Clan, a subject that has not been thoroughly documented before. By drawing on diverse primary sources, including oral traditions and anthropological findings, this research offers a richer understanding of the clan’s history. Second, it delves into the specific push and pull factors that drove migrations within the Niger Delta, adding nuance to broader theories of African migration. Third, this study illuminates how the clan maintained cultural continuity while adapting to new environments across generations, contributing to the broader understanding of cultural evolution and resilience.

Furthermore, this research explores the impacts of external influences such as trade and colonialism on the Western Nsit Clan, providing a ground-level perspective often absent in broader historical accounts. By analyzing the clan’s religious practices, totems, and customs, this study sheds light on how dispersed groups preserved connections to a shared origin, even as they adapted to changing circumstances. Focusing on a specific large clan within the Ibibio ethnic group adds granularity to the understanding of the region’s intricate social organization and inter-group relations, offering a more nuanced view of its cultural and political landscape.

Methodologically, this study advances an approach to researching African history by utilizing totemism and oral traditions as analytical tools, demonstrating their value in reconstructing and interpreting historical narratives. Overall, this research aims to deepen the understanding of the multifaceted history of the Niger Delta by closely examining the experiences of one significant clan over time. Through this micro-level analysis, this study contributes to filling gaps in the broader historical and anthropological literature on the region, offering both specific insights into the Western Nsit Clan and broader implications for the study of African societies.

The Nsit Clan is generally acknowledged as the largest Ibibio Clan (see

Figure 2). It was so extensive during the colonial era that the colonial government found it convenient to split it into two parts—Western Nsit, with a rallying point (or embryonic headquarters) at Mbiaso, and Eastern Nsit, with its headquarters at Odot. Nsit Clan of Ibibio has seven sub-clans spread into three local government areas and the Okon clan in the Eket Local Government Area Esen (1998). These sub-clans have their traditions of origin and migrations; hence, it would be proper that this work traces the origin and migrations of the Western Nsit Clan based on the existing sub-clans.

The name “Nsit” means “forest”. The clan derives its name from the kind of environment it situates. The Village Head of Ikot Obok Nsit maintains that “Nsit is a shortened form of “Nsidde”.

1 The name came as a result of the forest, which is a common feature of Nsit, until now, Nsit still has thick forests and bushes than any other place in Ibibio land”. Chief Isimin also states that “the clan is called ‘Nsit’ because of thick forests that abound in the area, even to date.”

2Although some people believe that Nsit means “pouring out in great numbers”, Offiong asserts that the name “Nsit” literary means troops, large company, flock.”

Obio-Offiong (

1958). The general opinion is that Nsit in Ibibio does not mean “pouring out”, but “forest”.

Nsit is the oldest single largest group in Ibibio land.

Udo (

1983). If the assertion is true, then the name “Nsit” was influenced by the wild environment of that time. If the assertion is anything to go by, Nsit would, therefore, mean people who live in a bushy or untidy environment. Thus, Nsit refers only to the land and not the people therein; even though the inhabitants now collectively accept to be so known, each group is more conscious of its tradition of origin and migration than to Nsit.

In a memorandum submitted by the people of Western Nsit, through the Nsit Ibom Traditional Rulers Council to the Governor of Akwa Ibom State in 2016, for the creation of more clans in Nsit, the people submit that:

Some customs and practices seek to regulate, through totems, the cultural differences in these clans. For instance, the people of Edeobom Clan did not eat cocoyam. It probably had to do with their hereditary abhorrence of certain plants from time immemorial, but the reality of modern living seems to restrict the totem to a few diehards! The same story goes for various Ibibio days for the collection of Palm fruits, for work on farmlands, for observances and rituals of the Ekpo masquerade, and for traditional market days. Suffice it to say that this mode of life has successfully distinguished these people and lodged them within the definition of the term “clan”. We want to rest our case on the proof of our existence as clans from time immemorial and the fact that these clans had been recognized and gazetted and given Heads who were recognized as Group Heads by the Esuene Administration but later annulled by the probative and re-probative military legislative and administrative machinery.

3The above-quoted memorandum affirms the position that Nsit is made up of diverse people. Hence, in this work, the origin and migration of Nsit are studied based on groups (or sub-clans). However, it is pertinent to assert that since Afaha, Oboyo, Nung Oku, Ibedu, Ibiakpan, groups, etc., who are also found in their numbers in the geographical delineation called Nsit, are also found in other Ibibio clans, suffice to conclude that Nsit is not a homogenous people after all, but a collection or a conglomeration of different clans with diverse customs, totems, etc., but who, due to circumstances of their history, decided to close ranks without forgetting in entirety their origin. However, Nsit is divided into Western and Eastern Nsit. The two Nsit have seven sub-clans, viz: Afaha, Oboyo, Nung Oku, Okon, Ibiaikot, Ibedu, and Ibiakpan.

2. Origin and Migrations of Groups in Western Nsit

- (A)

Afaha: Afaha people and villages are found in great numbers in every clan and local government area in Ibibio land (in Akwa Ibom State and the Southern part of Cross River State). Perhaps this might have constituted one of the reasons why Noah submits that “the Ibibio are Afaha people”

Noah (

1980). Obio-Offong also makes a very weighty claim about the Afaha people when he states that “in most cases, the traditional heads of tribes and sub-tribes or clans of the Ibibio people can always be traced in genealogy to be directly or indirectly of the Afaha origin or kin”.

- (B)

The Afaha people of Ibibio migrated from Edik Afaha in the Usakedet (now called Isangelle) region of Cameroun. According to tradition, the Afaha people sailed down the Cross River to their present locale. Every historian interested in the Afaha history bases their submissions on oral traditions and legends. Scholars such as

Obio-Offiong (

1958),

Noah (

1980), and

Udo (

1983) rely on oral traditions and legends because of the dearth of written sources in this regard. The date of their migration is not known, But Obio-Offiong, himself an Afaha man, suggests an Akwa Akpa Uruan origin of the Afaha people. Akwa Akpa Uruan is somewhere around the bank of the Cross River. According to him, the Afaha people had dwelt there for generations and developed a civilization where agriculture and fishing flourished because of the fertility of the land and the richness of the sea in terms of seafood.

Although Obio-Offiong relies on the general legend of the Obio-Offiong family of Afaha to promote his discourse on Afaha origin, his work has given a clue to the origin and migration of the Afaha people of the Nsit Clan. He narrates why the Afaha people left Akwa Akpa, stating that during the reign of one great and powerful king, Offiong, there were constant periods of dangerous floods. This river was increasing in depth and volume and started overflowing its banks. This, together with erosion, which had also started to develop during this period, resulted in the destruction of spurs in the valley, and consequently, there was a strong effect of the tidal waves on the shores of Akwa,

Akpan (

2007). All these made the people homeless and their farms destroyed; coupled with constant family strife and precarious and miserable economic and social life, the Afaha people were forced to disperse to different directions of the sea and mainland.

Akwa Akpa Uruan, where Obio-Offiong claims to be the original home of Afaha, is situated opposite Edik Afaha in Cameroon. It can be deduced that the Afaha originated from Edik Afaha in Cameroun and migrated to Akwa Akpa Uruan, where Obio-Offiong claims they had developed a civilization before they were forced to embark on another migration in different directions.

The Afaha people sailed down the Cross River to Ibibio land through the Uruan corridor, where they settled with other Ibibio families until they were driven out by more numerous Igbo people who advanced southward towards Ibom in Arochukwu founded by the Ibibio people. Akpan (1973).

Upon leaving Ibom, the Afaha people found today in Ibibio land first settled in Afaha Ekpo Udo. Eteidung Idongesit Udofia asserts that almost all the Afaha villages in Ibibio land originated from Afaha Ekpo Udo. He maintains that “until recently, every prominent or blue-blooded Afaha person anywhere was interred in Ndoon Ọbọọń (former abode of kings) in Afaha Ekpoudo”.

4 That was the tradition. However, there is a consensus among the elders of Nsit that Afaha Ekpo Udo was part of the Mbiokporo Quasi-Imperium of Antiquity. Chief O. P. Essien, Chief Nicholas Edet Okon, Chief Ime Jimmy Akpan, and Elder Effiong Akpan Etoho, in different interviews, claim that Mbiokporo village comprising present Afaha Ekpoudo, Obio Nsit, Afia Nsit, Nduo Eduo, Mbak Nsit, Ikot Oku Ikono, Mbiokporo, Ikot Ntuen Nsit, Ediene Ikot Obio Imo, Obio Offot, Obio Etoi, Mbierebe Obio, Ekom Iman and Ikot Otong.

5 These places were then settled in the Mbiokporo quasi-confederacy, even though they migrated from different sections of West Africa. The majority of those who joined the confederacy have been the Afaha people. The majority of these villages seceded from Mbiokporo’s influence through war. For instance, Mbiokporo/Obio Offot, Mbiokporo/Oboyo Ikot Ita. Afaha Nsit/Obio Etoi; Mbiokporo/Mbierebe wars, etc.

It was from Afaha Ekpoudo and other Afaha settlements in the Mbiokporo confederacy that the Afaha people later migrated to their present settlements in Nsit and outside Nsit. The Mbiokporo 2, Afaha Offiong, Afaha Ikot, Ikot Iwud, Afaha Ikot Ede, Afaha Abia, and all the Afaha villages in Western Nsit, except a few in the Ibiakpan group, trace their ancestries to villages in the former Mbiokporo Quasi-Imperium. There is no village in the Mbiaso and Ndiya area of Nsit Ubium without a parent village in what is described here as Mbiokporo Quasi-imperium in the Asang Court Area.

The ‘Mbiokporo Quasi Imperium or Confederacy’ was a center of religious activities centered around the Anyang deity. The confederacy comprised the three original groups of Nsit, viz: Afaha (Mbiokporo, part of Afia Nsit, Afaha Ekpoudo, and Obio Nsit), Oboyo (part of Afia Nsit known as Owok Oboyo) Mbak, and Ikot Otong) and Nung Oku (Nduo Eduo, part of Ikot Ntuen, Ikot Oku Ikono and Ediene Ikot Obio Imo). This confederacy formed a watershed from where groups and villages in Ibibio land, especially in Western and Eastern Nsit, subsequently originated. That is why Mbiokporo groups are in the Offot Clan and Ikono Clan of the Uyo Local Government Area. Ediene in Uyo and Itak also have their major families, which migrated from among villages in the former confederacy.

6Today there are four villages in Ibibio land named “Afia Nsit”. These are Afia Nsit I (former member of Mbiokporo Quasi-Imperium), Afia Nsit Udua Nkor, Afia Nsit Atai in Nsit Ubium and Afia Nsit in Eket Local Government Area. These villages are Afaha, though a section of Afia Nsit I, known as Owok Oboyo, and a section of Afia Nsit Udua Nkor, known as Ndito Ita, are of Oboyo extraction. In Afia Nsit I, the Ikot Nkwo and Nung Okubo families are Afaha; Nung Oku Mben-Idim families are Nung Oku, while Owok Oboyo families are Oboyo. In Afia Nsit Udua Nkor, Ikot Okpong families are Afaha people, while the Ndito Ita section is Oboyo. The same structures are found in the other two Afia Nsit villages. The Nung Inyang Okpong family of Afia Nsit Atai and other families in Ikot Akaba and Ekwo are Afaha. However, there are villages in Nsit who claim Afia Nsit ancestry. These villages are Ikot Edibon, Ikot Abasi Ufat, Ikot Asat and Ikot Obio Ndua. Afia Nsit are Afaha people, but as they moved away from the original Afia Nsit, which is Afia Nsit I, they took a new identity for themselves. In Nsit Ubium, they are known as Afia Nsit Group instead of Afaha. In Eket, Afia Nsit is grouped under the Eket Afaha Clan. Nung Akpan Obio Ukem in Ikot Okpong in Afia Nsit Udua Nkor, according to Okuku Essien Akpan Ebong of Obio Ibiono, originated from Akpan Obio Ukem in Obio Ibiono in Ibiono Ibom Local Government Area.

7Afaha Offiong, the headquarters of Nsit Ibom Local Government Area, traces its ancestry to Afaha Ekpoudo. They claim to have originated from the family of Obio-Offiong in Afaha Ekpoudo. It was from Afaha Offiong Village that Afaha Abia and Ikot Akpan Nsit originated. According to Tradition, some members of the Obio-Offiong family moved further and founded Afaha Abia and formed a ruling family named Nung Obio-Offiong. In time, members of other families in Afaha Offiong joined their kins in Afaha Abia and established the Iyoho family. It seems that it was an intra-family war that scattered members of the Obio-Offiong family in Afaha Offiong. Some flee as far away as Mkpanak in the Ibeno Local Government Area and Ekpene Ukim in the Uruan Local Government Area.

The eight villages that constituted Afaha Nsit II in Nsit Ibom Local Government Area migrated from Afaha Ekpudo in the former Mbiokporo Quasi-Imperium. Afaha Ikot, Afaha Ntup, Afaha Ikot Udo Akpan, and Afaha Ikot Uba trace their genealogies to one Otok Akpan Akpan Ekpudo Inyọọn Ikaan Obio Ikot from Afaha Ekpudo. The existence of Ndoon Otọk Akpan, Akpan Ekpudo (Otok’s former abode) confirms the existence of a man by that name. Also, Afaha Ikot Ede and Ikot Edor trace their genealogies to Ede Obio Ikot and Edor Ntuanga Afaha, still in Afaha Ekpudo. All Afia Nsit villages in Nsit and Eket are Afaha.

The common totem of Afaha anywhere is the elephant. “Totemism is said to have been a methodological device used by historians interested in African history to reconstructing the history of many societies”. In the classic anthropological sense, totems link people into groups under an emblem of a common totemic species and set them apart from groups claiming common origin. This means that groups or clans that revere the elephant, their modern geographical spread notwithstanding, have a common origin or relationship in the remote past. Thus, “totemism suggests that man has a series of totems which constantly reminds him of his relationship to an ever-expanding group of people. Totems are emblems for the clan as flags are for nations”,

Akpan (

2018).

Apart from the totem, which every Afaha village in Ibibio land and Igbo land share, the Afaha people have a common deity called “Akwa”. The deity is represented by/with a stone called “Itiat Afaha”, and it is situated at Afaha Ekpoudo; hence, the reason why it is believed that the original Afaha in Ibibio land is Afaha Ekpudo.

8 Afaha everywhere venerate the Akwa Afaha deity and rever elephant as their totem. These are what give them a common ancestry.

B. Oboyo: The Oboyo Group of Nsit has Uruan ancestry. Their culture and tradition before now were hinged on the Ekpe Secret Society while their neighbors were Ekpo. Before the down of the 18th century, the Oboyo culture had been influenced by neighboring cultures. The Totem of Oboyo is Ndukpo (African black kite), apart from Atan (palm civet), the general Nsit totem.

Tradition common among the people of Ita Uruan and Ndito Ita in Afia Nsit Udua Nkor has it that the Uruan people (Oboyo) found in Nsit ran away from Ita Uruan because a big tree (Mahogany), which their leaders attempted to fell fall on them and killed scores (of them). According to the tradition, it was their practice to fell a big tree once every seven years. It was their practice, too, to prevent such trees from falling on the ground; hence, all the family must be present to help prevent the tree from landing on the ground. So, on that fateful day, luck ran out of them; hence, the gigantic tree fell on them. Thus, “it was the practice in those days to show bravery and strength in a bid to intimidate the neighbors since pre-colonial Africa was primitive and characterised by war”.

9Tradition also has it that some surviving members of Nung Obio Ekpene and members of Nung Obio Asang fled the village and settled in Nsit. Today, the original abode of Nung Obio Ekpene is desolated and deserted. Upon their arrival in Nsit, they adopted a new name, perhaps because of their leaders. There is controversy over the original settlement of the Oboyo people upon stepping on what is today known as Nsit. It is held that the original settlement of Oboyo people was Oboyo Ikot Ita in Nsit Ibom Local Government Area, and Mbak was the center of dispersal of Oboyo people as it is situated within the Mbiokporo Quasi-Imperium, which every Nsit village point at as its original abode. Oboyo Ikot Ita, which literary means “Oboyo, the people of Ita”. The first settlement of the Oboyo people upon arriving in Nsit was Afia Nsit I. But for the people of Owok Oboyo in Afia Nsit, I believe that their ancestors migrated from Oboyo Ikot Ita, led by Udo Mkpeng. There is Akpan Mkpeng (that is, the Elder or upper Mkpeng family) in Oboyo Ikot Ita.

10Today, Oboyo Ikot Ita is a section of a village known as Oboyo Urua. The Oboyo Urua or Obo Urua was a corruption of Oboyo Uruan. No oral tradition points to the existence of Urua (market) in the past except for the contemporary market called Urua Offiong Aran in Mbiakot. In any case, if there used to be a market in the area that could have warranted the name “Obo Urua”, such a market would have been called “Urua Obo” and not “Obo Urua”, in line with the Ibibio System of naming. There are Urua Obo in Annang, Urua Etaha in Oboetim, etc.

Obo Urua was a corruption of Oboyo Uruan.

Ukpong et al. (

2001) opine that Uruan derived its name from “Urua” (market). This, therefore, means that originally, the Uruan community was known as Urua; thus, any person who migrated from there was known as “Owo Urua” (someone from the market). For Oboyo people who migrated from Uruan to be called “Obo Urua,” was not out of place.

In separate interviews, Ekemini Wilson and Elder Udom

11 held that the area used to be called Obo Uruan, but for fear of segregation, hate, or persecution, the name was tactically changed to Obo Urua to dissociate them from Uruan or to hide their conspicuous Uruan identity. Another source blamed the colonialists for the name change. The name was lost when the village was divided into Obo Atai and Oboyo Ikot Ita.

Accordingly, it was deposed by the Village Head of Oboyo Ikot that “his kinsmen are in Ita Uruan,” Which means that Oboyo Ikot Ita and Ita Uruan are related biologically and socially. He emphasized the relationship existing between the two communities by stating further that Oboyo Ikot Ita and other Oboyo villages in Nsit had their lives centered around Ekpe society and that there was an Efe Ekpe Oboyo (Ekpe Hall for Oboyo) in Oboyo Ikot Ita. Obong Effiong Edem Umoh of Obo Atai was an Obọọn of Ekpe Essien Oboyo Uruan. Other members of Ekpe in Oboyo before colonialism were Obong Udom Akpan Umoren of Oboetim Ikot Ekong, Asuquo Etok Udo, Asukwo Udo Obot, Ndaeyo Etok, Obong Bassey Udosen, etc., all of Obo Atai.

12Some families in Oboyo Ikot Ita, Asang Nsit, Ikot Otong, Mbak and the six villages constituting Oboetim in Nsit Ubium LGA, viz: Ukat Aran, Ikot Ada Okop, Ikot Enwang, Ikot Inyang Eti, Ikot Ekpan and Ikot Etim dispersed from Oboetim Nsit in Nsit Ibom Local Government Area. Although Ikot Enwang in Nsit Ubium originated from Mbak Nsit, it is believed that some families originated from Oboetim. The family, known as Ekpene Ukim in Ukat Aran, migrated directly from Ekpene Ukim Village in Uruan.

13Ikot Idem Nsit and Obontong originated from Mbak Nsit. That explains why they have the same families, such as Nung Ebok, Nung Ekim, etc. Nkwot Nsit originated from Asang Nsit; hence, the controversy over where it belongs is entirely political. The founder of Nkwot was one of the sons of Ukpe from Asang Nsit. Although, there are families that migrated from Ikot Idem Mbak Nsit, Ukat Nsit, and Iman Clan to the village. Nkwot is the parent village of Nkwot anywhere in Ibibio land. The deity of the Oboyo group is Adiaha Ita. It is situated in Owok Oboyo in Afia Nsit and Oboyo Ikot Ita; even though the name of the deity has been changed with time to Adaha Ato, it still maintains its name in Ita Uruan.

14C. Nung Oku: The group collectively known recently as Nung Oku Anyang is a fusion of two priestly groups, Nduo Eduo and Edeobom, perhaps, following Esen’s postulation in 1998 in a souvenir program in honor of the late Clan Head and Paramount Ruler of Western Nsit, HRM Nsobom Tom Essien Ubong III when he states inter-alia, thus: “The name “Nung Oku Anyaang” which was thrown apart during the last few years of the late Nsobom’s reign as a replacement for the inappropriate and misleading name “Edebom” for the Oku Anyaang Group in Nsit… will win general acceptance and achieve universal usage”.

15It is believed that Nung Oku people migrated into Nsit in two waves. These were the Edeobom and Nduo Eduo groups. The parent village of Edeobom is Ikot Ntuen Nsit. The ancestors of Ikot Ntuen originated from Nung Oku Mben Idim in Afia Nsit I. Their tradition is that “Ikot Ntuen, the mother of Edeobom group of villages, swapped their habitation with Afia Nsit people”.

16 But a contrary view says that not all Afia Nsit swapped their settlement with Ikot Ntuen; only the people of Nung Oku Mben Idem carried that out.

17 From this swapping theory, it could be deduced that Ikot Ntuen originated from Afia Nsit I because, one, there is still a stream in the Nung Oku Mben Idim section of Afia Nsit I named after Ikot Ntuen Nsit. The stream is called “Idim Ikot Ntuen”. Two, the fact that Edeobom villages trace their ancestries to Nung Oku instead of Edeobom indicates their Nung Oku/Afia Nsit ancestry.

On the other hand, Nduo Eduo, another priestly family in Nsit, is believed to have migrated from Ukwa, a clan in the northern part of Ibibio land (in the present-day Cross River State of Nigeria). Nduo Eduo village was originally surnamed “Nduo Eduo Ukwa Ikot”, until the rise of Mbiokporo Quasi-Imperium when it was changed to Nduo Eduo Obio Nsit. The village was originally a part of Mbiokporo I Quasi-Imperium, which was excised from the latter (perhaps after the dissolutions of the confederacy) because of its significant role in Nsit. Akpabio and Akpabio believe that “to fulfil his socio-religious functions, Eduo went out of Obio Nsit community and founded his settlement called Ndueduo (sic) till this day”. Though it was part of Mbiokporo I, Nduo Eduo was never an Afaha village, even though there is a linkage.

18While the Nduo Eduo people were charged with the responsibility of administering Anyaang (the Chiefest deity of) Nsit, Edeobom people were in charge of the administration of minor deities such as Ukpa Edeobom, Uboekong, Itiat Ntuen, and Obom Abang. The original abode of Nduo Eduo was Esa Anyang, while that of Edeobom was Nung Oku Mben Idim in Afia Nsit I before they moved to Ikot Ntuen through the leadership of Ntuen.

19 Udoekong Udo Nnan contends that “Ikot Ntuen is the mother village of the Edeobom Group of villages in Nsit. Other Edeobom villages migrated from Ikot Ntuen.

20 However, Ikot Ntuen is said to have originated from Afia Nsit”, and is believed to be the parent village of Edeobom from where all other Edeobom villages originated.

21Nung Oku people, just like Afaha, Oboyo, Ibiakpan, and others, are found in great numbers in every clan in Ibibio land. In Nsit, the group is divided into two: Edeobom and Nduo Eduo. There are eight Nduo Eduo villages in Nsit land. These are; Nduo Eduo Obio Nsit, Ikot Nya, Ikot Ebre, Ikot Obio Etan, Ndiya Ikot Ukap, Ndiya Ikot Akpafuk, Ndiya Usang Inyang and Nduo Eduo in Okon Clan in Eket.

22Edeobom is a fusion of two Ibibio words: Ede and Obom. “Ede” means bravery and valor, while “Obom” means a pole used by an Ibibio man to support the roof of his house. In this case, Obom connotes protection or shield. Chief Stephen Akpan, while listing the families in his village (Okwo Nsit), stressed that Nung Ede (his family) is “the family of brave men”. He maintained that Ede is an old usage of the word “Ide”.

23Many villages in Ibibio land are either prefixed or suffixed with “Ede” or Ide”. Examples: Afaha Ikot Ede and Ede Obom village in Nsit Ibom L.G.A; Edeobuk in Eket LGA; Ikot Ide Akpakpan in Ibesikpo Asutan L.G.A; Ikot Ide in Ukanfun L.G.A; Ikot Udo Ide in Nsit Ubium L.G.A; Ikot Udo Ide family in Idiaba village in Nsit Atai L.G.A, etc. Writing about names in Ibibio,

Essien (

1986) maintains that the cultural significance of names in Ibibio can be viewed from two perspectives, namely, what names mean to the native Ibibio speakers and what the names themselves reveal about the people’s culture. He goes on to say that A great many names in Ibibio are related to the religion and philosophy of the Ibibio people. These names reflect the practices that arise from religion and philosophy and the religious and philosophical ideas. The Ibibio are intensely religious; perhaps the best word to describe the Ibibio people’s attitude to God is ‘deicentric’.

It could be deduced, therefore, that Edeobom emanated from the eccentricity of the bearers because besides their priestly services to the minor deities of Nsit, they also, in a rather low-key fashion, attend to Uboekong, which is the deity of every Nung Oku Group in Ibibio land.

The natives of Edeobom village in Mbiaso Court Area trace their route to Ikot Ntuen Nsit and hold that after leaving Ikot Ntuen, their ancestors settled in Anyam Nsit before dispersing to their present settlement. Evidence abounds, pointing to the fact that Edeobom is a lineage that spread out from Ikot Ntuen with a separate ancestry from Nduo Eduo. There are many Ikot Ntuen villages in Ibibio land, such as Ikot Ntuen Oku in Uyo, Ikot Ntuen in Oruk Anam L.G.A, Ikot Ntuen in Nsit Atai, Ikot Ntuen in Oku Iboku, etc., and according to

Ukpong et al. (

2001),

Udo (

1983) and

Ekarika (

2014) they are priestly families in Ibibio land, especially in Annang section. These priestly families are collectively called “Nung Oku”; hence, if Ikot Ntuen in Nsit from where Edeobom emanated, has any biological and social relationship with any priestly family in Ibibio (which is most likely), then it can be concluded that Edeobom people migrated from among those priestly families in the remote past and settled in Afia Nsit before they moved to Ikot Ntuen where they acquired a new identity.

From the Edeobom village, some people migrated to the Ndiya axis and founded another Edeobom, which is today grouped under Ibiakpan. There are many Edeobom families in the Ibiakpan villages of Nsit Ubium L.G.A. For instance, a section of Ikot Usobak of Ikot Udo families in Ikot Imo village migrated from Edeobom village in Mbiaso Court Area of Nsit Ibom L.G.A. According to Billy Mkpouto, all the families that make up Ikot Imo in Nsit Ubium Local Government Area migrated differently. Accordingly, Ikot Udo’s family left Edeobom I to the Mbiaso Court Area of Nsit Ibom. It was from Ikot Udo in Ikot Imo that some people moved further and established Edeobom village in Nsit Ubium.

24There was a period in Nsit history when the name “Edeobom” replaced “Nung Oku” such that the Nduo Eduo group almost became extinct. It is, however, believed that the name “Edeobom”, used to refer to the Nung Oku people, “is a misnomer”. It is against that backdrop that Esen maintains that.

The name “Nung Oku …which was thrown apart during the last few years of the late Nsobom’s reign as a replacement for the inappropriate and misleading name “Edeobom” for the Oku Anyaang Group of Nsit… in Asang, Mbiaso, and other Districts of Nsit…, will win general acceptance and achieve universal usage…”. Essen (1998).

But Nsit tradition does not recognize any Edeobom village as an “Oku Anyaang” village because no Anyaang priest has ever hailed from any Edeobom village but from Nduo Eduo. But Edeobom is Nung Oku, not of Anyaang, but of other minor deities.

Villages like Ikot Oku Nsit, Anyam Nsit, Okwo Nsit, Obiokpok Nsit, Ikot Offiok Nsit, Ekpene Ikpan Nsit, Ikot Offiong Nsit, Ikot Obok Nsit, Nditung Nsit, Ikot Obio Asanga, Ikot Odiong Nsit and Ikot Obio Edim also belong to Edeobom and claim Ikot Ntuen Nsit as their place of primary or secondary migrations.

25 Ikot Ntan Nsit is grouped under the Edeobom group of villages simply because, according to their tradition, their ancestors took wives from Edeobom villages of Ikot Ntuen and Ikot Oku Nsit and were also assisted by Ikot Oku Nsit warriors to claim the land they presently occupy from Ekom Iman.

26 The people of Ikot Ntan are said to have migrated from Ntan Ekere in Ibiono Ibom Local Government Area.

There are Edeobom families of Ikot Obio Edim descent in Mbiakot Nsit. Their abode is where the African Church is currently situated in Mbiakot Nsit. All the families own plots of land in Ikot Obio Edim. There are also Nduo Eduo people in Ikot Obok Nsit. There is the presence of Afaha people in Ikot Obok and Oboyo people in Ikot Obok, too. The Ebre Family is Nduo Eduo because their ancestors migrated from Ikot Ebre. The Nung Essien in Nung Umana migrated from Mbiakot (an Afaha village). Nung Afe in Nung Amaunam migrated from Oboetok Nsit (an Oboyo village). What unites the two Nung Oku groups are the priesthood and a common totem, which is the cocoyam.

27D. Ibiakpan: The ancestors of the Ibiakpan Group of villages found in Nsit today are said to have migrated from Ibiakpan in Abak and Ikot Ekpene LGAs in the remote past. There are twenty Ibiakpan villages in Western Nsit (Nsit Ubium Local Government Area) and one in Eastern Nsit (Nsit Atai Local Government Area) named Ibiakpan.

But

Udo-Essien (

1983) also gives another perspective on the migration of Ibiakpan to Nsit. While he acknowledges that Ibiakpan is originally from Abak or Ikot Ekpene, he argues that they arrived in Nsit land via Eket, asserting they traveled by sea. The route through which the Ibiakpan entered Nsit is inconsequential and cannot detain us here. What concerns us is the origin of the group, which Udoh himself has agreed with the Annang theory.

Upon entering Nsit land, the Ibiakpan people formed their first settlement in Atan. Hence, Atan is the ancestral home of all the Ibiakpan villages in Nsit. War and internal wranglings explain why they dispersed from Atan and founded new settlements, which later became villages.

Edeobom village in Nsit Ubium Local Government Area migrated from Edeobom in Mbiaso Area, but because of its location amid Ibiakpan villages and the fact that some families in Ikot Imo and neighboring Ibiakpan villages had found their way and settled there, it is now regarded as an Ibiakpan village.

28Eteidung Udousoro of Ikot Ekpene Udo in Ibiakpan contends that the “Ibiakpan people are biologically Annang”. According to him, the people came for hunting and farming and refused to return because they fell in love with the serenity of the environment and the favor they obtained from the Anyaang deity since the people were deicentric and nocturnal in all facets. Four groups of people founded Ikot Ekpene Udo, hence their pattern of settlement inwards, which indicates that they share no common ancestry but proto-ancestry.

29The majority of those who founded Ikot Imo migrated from Abak. According to Oral tradition, the Ikot Usobak family in Ikot Imo was founded by a man called “Usọ Abak”. Uso is an old Ibibio word for father or man. So, the name “Uso Abak” means “Father or man from Abak”. From Abak, Usobak first settled in Ikot Etobo before migrating to Ikot Imo to form one of the families. However, some sections of Ikot Usobak migrated from Edeobom I in Nsit Ibom Local Government Area. Ikot Aniema family migrated from Ikot Ekpene Udo. Ikot Udo in Ikot Imo migrated from Edeobom I in Nsit Ibom.

30Confirming the tradition of Annang origin of Ibiakpan in Nsit, Joseph Ukpong believes that it is a known fact among the Ibiakpan people of Abak that people migrated from Ibiakpan in Abak to Nsit. Twenty Ibiakpan villages constitute Western Nsit, and nine are grouped under a moiety, “

Itreto”. Itreto is a corruption of Itighe eto (that is, tree stump). Oral tradition has it that there used to be two big trees used in curing smallpox and chicken pox in the area before the Europeans arrived in Ibibio land. So, when a native court was built in the area (on the very spot where the log was), it was named “Native Court, Itreto”. The Court has nine villages in its jurisdiction.

31E. Okon: Okon (Pronounced “Ọkọọn”), now a part of Eket Local Government Area, is one of the groups in Western Nsit and was hitherto a part of Western Nsit until the 1976 Local Government Reform and Boundary readjustment when the area was annexed to Eket following agitations by the people who opted to be under Eket Administration because of their proximity to Eket than to Etinan Division which Western Nsit was hitherto a part.

The Okon people live within the vicinity of Eket because, according to

Obio-Offiong (

1958), from the main Nsit, they started to disperse and at the same time trekking in different directions towards the seashore and the river bank “to seek for their brothers and relatives who had separated from them to different directions of the sea and river during the great dispersal”. According to him, “it was under this circumstance that a section of Nsits (sic) trekked in a southwards direction towards the sea”.

Its early migration history, just like those of other Nsit groups, is obscure; it has been speculated that migration of Nsit people (who are now called Okon) into the supposedly Eket territory antedates the Portuguese exploration of the Atlantic Ocean in the 15th century AD. However, migrations into the area were gradual and never an exodus. At first, individual hunters from Asang Area, especially within the Mbiokporo Quasi-Imperium, were the first set of people to discover the uninhabited land. In their quest to carry out their businesses well, they later returned to their respective villages in the Asang area and brought their immediate family members.

32 The hunters were later joined in the area by fishermen, mainly of Oboyo stock from Oboetim. Ikot Okudom people are said to have Oboyo (Uruan) ancestry.

Members of the Mboho Ndito Nsit Worldwide (A Socio-cultural/Socio-Politial group) in the 2014 Souvenir assert that the first contact the Ekid people made with the central Ibibio was that with the Nsit people of Okon Clan, who were regarded as “Nsit Ibie” by the Ekid (Eket) people. It seems that the Ekid people did not consider it necessary to cross the Obiota River—a tributary of the Qua Iboe River—to this other side, hence the reason the area was left unoccupied until the more numerous Nsit moved in. This assertion might be correct because Ekid’s (Eket) occupation of the South antedates the arrival of the Okon people in the area.

Like all other groups in Nsit, the Okon clan is “heterogenous”. Being Ibibio and speaking and comprehending the Ibibio language makes them homogeneous. Conversely, they are heterogeneous due to the clan’s division into four village groups with disparate migration and origin narratives. The names of these village groups are Nduo Eduo, Nung Uko, Nung Obio Ata, and Nung Osufok. Two of the four villages venerate Anyang Nsit; hence, Nung Osufuk’s claim of Iman heritage is debatable. However, the Nduo Eduo in the Okon clan migrated from Nduo Eduo in the defunct Mbiokporo Quasi-Imperium, although the family known as Nung Ekwo belongs to the Akiki group in Eket. But even at that, the Ekwo family in Nduo Eduo has a biological linkage with the Ekwo lineage of Afia Nsit Atai in Nsit Ubium,

Abasiattai (

1991).

Ikot Ataku village in Okon, according to

Okoko (

1988), came from Ubium. The fact remains that smaller groups are always swallowed up (or submerged) in the larger groups; thus, different groups with different backgrounds in Okon, just like every other group, had been acculturated and assimilated into Nsit. The Okon Clan is mostly peopled by elements from Afaha, Nung Oku, Oboyo, Ibiakpan, etc., either from Nsit or Ubium or Iman or Eket. But irrespective of wherever they migrated from, they have been submerged by Nsit tradition and culture, perhaps because of the latter’s numerical strength. Thus, the culture, tradition, and belief system of the Okon people are Nsit and nothing more.

33Nung Itam family of Ikot Abasi in Okon are believed to have migrated from Itam, probably from Ikot Abasi Itam in Itu L.G.A. However, probably, Ikot Abasi in Okon, Ikot Abasi in Itam (Itu L.G.A), and Ikot Abasi in Etinan have Uruan roots. Although some of them oppose their Uruan ancestry probably for fear of segregation, lack of linking proof, outright lack of knowledge of their history or politics, or a combination of all,

34 the fact is that in the years preceding the European invasion of Africa, there were waves of migrations across Ibibio land as a result of war and adventures.

Umoh-Faithmann (

1999). The Uruan people migrated mainly for adventures and fishing. Mostly, Ndon Ebom, Ita Uruan, Issiet, Mbiaya, Ibiaku, etc., were at the forefront of migrations. Some members of the Ikot Abasi family from Ndon Ebom, with others from Ita, moved to Itam and initially settled in the area now known as Nung Ukot. From there, other Ndon Ebom families moved and founded Ikot Ebom Itam. Those who migrated from Ikot Abasi family in Ndon Ebom grew and formed Ikot Abasi Itam. The Nung Itam family and other families in today’s Ikot Abasi village in Okon Clan migrated from Ikot Abasi Atam; those in Nung Atim crossed to the Asang Area and formed Oboyo villages. Thus, Ikot Abasi village, perhaps, until recently, particularly the Nung Itam family, regarded monkeys as their totem animal in line with the Itam tradition. Okon people generally venerate the Anyang Nsit deity.

Usage and Significance of Totems Among the People35

Totems Confirm

Erim (

1998) hold significant cultural, social, and historical importance in the regions and periods discussed in this article, particularly within the Ibibio ethnic group and the broader Niger Delta area of Nigeria during pre-colonial and colonial times. The usage and significance of totems can be understood through several key aspects:

Cultural Identity and Group Cohesion: Totems serve as emblems that link people into groups under a common totemic species, fostering a sense of identity and belonging. For example, the elephant is a common totem among the Afaha people, signifying their shared ancestry and relationship. This collective identity helps maintain cohesion within clans and sub-clans despite geographical dispersion.

Historical Narratives and Origin Stories: Totemism acts as a methodological device used by historians to reconstruct the history of societies, especially regarding their origins, migrations, and inter-group relations. Totems are not merely symbolic; they are embedded in the oral traditions and cultural practices of communities. As noted in this article, clans or kindred groups revering the same totem, such as the elephant, are considered ethnically related in the past, providing clues to ancient connections and migration patterns.

Social Regulation and Norms: Customs and practices tied to totems regulate cultural differences among clans. For instance, the Edeobom Clan traditionally refrained from eating cocoyam due to hereditary abhorrence, illustrating how totems can influence dietary habits and other social norms. These practices help distinguish one clan from another, reinforcing distinct identities within a larger ethnic group.

Religious Significance: Totems often have religious connotations, linking communities to specific deities or spiritual beliefs. The veneration of the Anyaang deity among the Nsit Clan exemplifies this, where religious practices centered around the deity contribute to the clan’s unity and cultural continuity. The belief in the potency of such deities often drives collective actions and decisions, impacting migration and settlement patterns.

Symbolic Representation: In a classic anthropological sense, totems function similarly to national flags, representing the clan as a unified entity. They remind individuals of their relationships with an ever-expanding group of people, maintaining social bonds over generations. This symbolism is crucial for preserving cultural heritage and passing down traditions.

Migration and Settlement Indicators: The presence of specific totems in new settlements indicates ancestral origins and historical movements. For instance, the widespread presence of Afaha villages with the elephant totem across Ibibio land suggests a common migratory path from a central origin. Tracking these totems helps historians trace complex migration routes and understand how dispersed groups maintained connections to their roots.

Political and Administrative Functions: Totems also play roles in traditional governance structures. Leadership and ruling families often trace their genealogies to totemic ancestors, legitimizing their authority. The Obio-Offiong family of Afaha, for instance, established ruling dynasties linked to their totemic lineage.

In summary, totems in the context of the Ibibio people and the Niger Delta region were multifaceted, influencing various aspects of life, from cultural identity and social regulation to religious practices and political legitimacy. Understanding totems provides valuable insights into the intricate tapestry of historical narratives, migration patterns, and socio-political organization within these communities.