1. Introduction

This article explores the principles and practices of Tewahedo epistemology, presenting it as a transformative framework with global relevance for decolonizing academic literacy in higher education. At its core, Tewahedo—meaning “oneness” or “unity”—offers a holistic integration of academic literacies: visual, oral, written, and spatial (

Cope and Kalantzis 2000). In this Ethiopian knowledge system, literacies are not isolated technical skills but disciplinary and cultural tools fostering meaning-making and shared knowledge production. By engaging with Ge’ez language concepts within historical Tewahedo educational traditions, this study demonstrates how this decolonial epistemology provides an alternative to dominant decontextualized, generic approaches to literacy in universities globally. Tewahedo can be considered a decolonial strategy because its non-dualistic (see

Lewis 2024) nature challenges the colonially induced, artificial separation of academic and cultural knowledge. As the name Tewahedo means, the framework fosters a unified integration of Indigenous epistemologies, resisting colonial ideological dominance, and promoting communal learning environments, reminiscent of Africa’s pre-colonial era. The article also highlights Tewahedo’s potential to address systemic issues in African and global higher education, including high attrition rates and cultural alienation.

The coloniality of knowledge throughout African and global universities where Eurocentric norms often dominate the development of academic literacy results in many students experiencing disciplinary and cultural alienation (

Cornel et al. 2022).

Leibowitz (

2017) concurs by arguing that the imposition of Western epistemic models in Africa has caused great harm, including students’ experiences of teaching and learning. Scholars describe colonially induced alienation within education in several ways.

Asante (

2010) terms it epistemic dislocation, where Indigenous students struggle to identify their familial, communal, and linguistic epistemologies with academic practices.

Asea (

2022) refers to alienation as epistemic coloniality, emphasizing how African scholars confront institutional cultures that marginalize Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKSs) while privileging Global North ideologies. This misalignment coerces culturally diverse, multilingual, Indigenous students and educators, from across the globe, to abandon their Indigenous identities and ancestral interpretations of disciplines.

Epistemic dislocation—the gap between students’ Indigenous knowledge frameworks and Eurocentric paradigms—poses a significant barrier to their advancement in higher education and academic literacy development. Reflecting on wa Thiong’o’s claim that Global North, colonial educational ideologies result in epistemic violence, intentionally aiming to replace Indigenous Knowledge Systems with European paradigms,

Al Attar and Abdelkarim (

2023) describe coloniality as entrapment in thought. This entrapment is reflected in South Africa, where annually an average of 25% of students drop out of universities (

Mabunda 2023). In Ethiopia, nearly 40% of students entering higher education are at substantial risk of attrition (

Tamrat 2022). In the United States, only half of the students who enroll in higher education complete their degrees (

Demetriou and Schmitz-Sciborski 2011). In Germany, 28% of students in bachelor’s programs drop out (

Heublein 2014). While about half of the young population now has access to higher education in France, only 37% graduate (

Gury 2011). The pervasive issue of colonial knowledge systems is not just an African issue but a global concern, impacting education worldwide, even in Europe, where these structures originate.

For

wa Thiong’o (

1986), coloniality operates as a cultural bomb, erasing Indigenous knowledge and languages while undermining the capability of educators and students to resist epistemic injustice in academic literacy. This systemic alienation, as

Starks (

2024) argues, is exacerbated by instructors’ reliance on Eurocentric frameworks, deepening epistemic dislocation among students globally. Similarly,

Pratt and De Vries (

2023) demonstrate how coloniality fuels attrition and ethnic marginalization for scholars in Australia and southern Africa, corroding their academic identities, a phenomenon

Asea (

2022) frames as imposed assimilation, manifesting in intellectual alienation and imposter syndrome. Such inequities privilege students from dominant socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, echoing

Lea and Street’s (

2006) assertion that academic literacy is inseparable from power dynamics. By exposing these parallels across regions,

Pratt and De Vries (

2023) underscore the urgency of decolonizing pedagogy to counter Ngugi’s “cultural bomb” and its global repercussions.

This article argues that Tewahedo’s unifying epistemology offers a transformative response and an alternative academic literacy model with global relevance to address the colonial cultural bomb and its repercussions in higher education, including student attrition, epistemic alienation, and unequal disciplinary power dynamics. Such a transformation in universities is essential to prevent the colonial influences, embedded in unequal institutional hierarchies, from influencing global societies, where problems such as authoritarianism, vast economic inequality, and war require solutions based on innovative knowledge.

Rooted in communal learning, liturgical symbolism, and multiple forms of literacy, ancient Tewahedo epistemes historically provided a sense of academic belonging in Ethiopia by using teaching methods that prioritize the needs of novice scholars. This ethos differs from colonial educational models, which deliberately aimed to alienate students’ cultural and disciplinary identities. The Tewahedo knowledge system is significant for developing novice scholars’ literacies globally because it highlights the importance of inclusive and supportive educational practices that can help students from diverse backgrounds succeed.

Mulualem et al. (

2022) highlight that in Ethiopian Qene (writing) schools, operating within Tewahedo systems, both students and tutors (advanced students), under the mentorships of senior instructors, share responsibility for teaching and learning. This is one example of how Tewahedo aims to unify diverse actors, including community members, in knowledge generation.

Ethiopian Qene apprentice models resonate with the need for present-day university students to master collaborative literacies in both educational and professional contexts.

Mulualem et al. (

2022) argue that peer teaching and group learning are common features of Qene writing traditions. Singing and dancing are also common features of Qene educational practices (

Mulualem et al. 2022). Unlike the rigid, colonial-era academic literacy models that confine students to European languages in reading and writing, Tewahedo offers a distinct alternative. Qene educational models reflect this distinction by integrating multiple literacies reflecting ancient educational cultures worldwide. For example, pre-colonial martial arts that originated in Beijing, China facilitated students’ holistic development by focusing on resilience, a sense of community, and physical and mental needs (

Zhang et al. 2025). As is evident, coloniality of knowledge tends to institutionalize a single framework of knowing, whereas decolonial approaches create spaces for integrating local epistemologies and community-based ways of learning.

The persistence of colonial pedagogies in academic literacy development, including assessment, continues to suppress Indigenous epistemologies, languages, and ontologies worldwide. This is a decolonial concern, as

wa Thiong’o (

1986) claims such marginalization results in epistemic violence against Indigenous and African people. To transform these entrenched systems, educators should first recognize and interrogate enduring colonial influences in curricula, including multiple-choice testing that inadvertently privileges Global North epistemologies, often at the expense of Indigenous knowledge traditions. In response, this article proposes the Tewahedo framework—a decolonial approach that recenters Indigenous Knowledge Systems as a foundation for academic literacy. By rejecting the hegemony of Eurocentric models, Indigenous African educators engage in what

wa Thiong’o (

1986) calls “moving the center”. In so doing, educators decolonize academic literacy by repositioning Africa as the locus of knowledge production. Ultimately, the article advances Tewahedo as a global vision of decoloniality, where academic literacy serves as a bridge, rather than as a barrier, to epistemic justice and belonging.

4. Literature Review

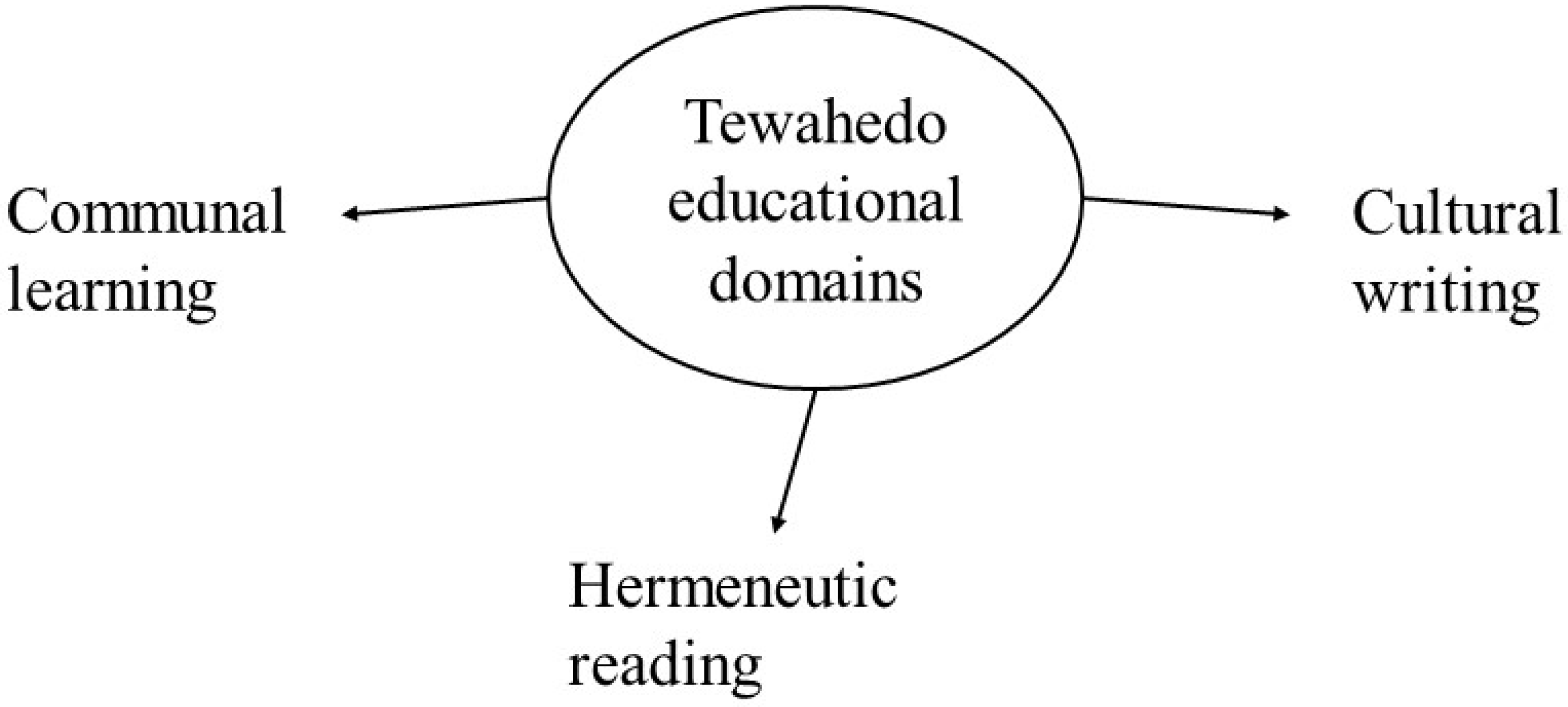

Analyzing the role of Tewahedo epistemology in contemporary academic literacy pedagogy reveals its decolonial potential (see

Figure 1). This alignment matters, for as

wa Thiong’o (

1986) contends, languages and literacies are not neutral tools but vessels of cultural values and principles. In this view, the current article identifies key decolonial benefits of Tewahedo epistemology, including its emphasis on communal knowledge, its approach to academic reading as a communal, interpretive dialogue, and its recognition of writing and other literacies as social practices, shaped by historical and cultural contexts. This article holds that decolonial principles align with the academic literacy model, which conceptualizes literacy as a social practice, shaped by institutional structures, cultures, and agency (

Lea and Street 2006). Tewahedo educational domains, shown in

Figure 1, are essential for global universities to foster inclusive and culturally relevant disciplinary environments.

Tewahedo, meaning “to make one” or “unity” (

Weldegzihabeher 2000), provides a valuable framework for enhancing academic literacies, especially for global first-year students who often struggle with feelings of social disconnection during their transition to university life (

Cornel et al. 2022). Scholars, including

Bangeni and Kapp (

2005) and

Chiramba and Nyoni (

2024), argue that students learning in diverse disciplinary contexts often experience universities and their homes as distinct cultural grounds, with varying ways of knowing, being, and communicating. As a result, there is concern that weak social and academic integration into higher education is a major contributor to first-year student attrition in higher education throughout the world (

Shcheglova et al. 2020). Decolonial frameworks critically address African students’ struggles with disciplinary belonging, echoing wa Thiong’o’s assertion that colonial languages function as tools of epistemic alienation—severing African and Indigenous learners from disciplinary knowledge and language’s broader societal roles.

Alternatively, core literacies that are practiced in Tewahedo offer valuable insights for international academic literacy developers aiming to reduce student alienation and disengagement and recenter Indigenous cultures, epistemologies, and ontologies in education. Doing so, with the support of Africa’s myriad languages, as argued by

wa Thiong’o (

1986), would enable educators to reclaim Indigenous identities, agency, and cultural autonomy. This may also address the challenge of attrition in higher education. To illustrate, in ancient Ethiopian Tewahedo traditions, transcribing sacred texts, publishing illuminated manuscripts, poetic writing, philosophizing, and storytelling are central to preserving ancestral knowledge and fostering communal unity (

Mulualem et al. 2022). These educational practices continue into the present age. Unlike colonial modes that enforce isolated learning and privilege European languages through rigid monolingual instruction, Tewahedo acts as a decolonial framework by centering communal knowledge transmission and affirming Indigenous linguistic diversity as foundational to education.

Tewahedo’s embodied literacies, called Qeddase (ቅዳሴ) in Ge’ez (liturgy in English), were developed to align Ethiopia’s priests, scribes, and local community members into a coherent cultural ethos. Embodied literacies resonate with

wa Thiong’o’s (

1986) decolonial theory as they facilitate the integration of language, experience, history, and cultural identity through physical engagement. By employing these multiliteracies (see

Cope and Kalantzis 2006), African scribes not only preserved Ethiopia’s epistemological and historical narratives but also strengthened the unity of their communities. This unity was achieved by engaging in intellectual dialogues and embodied academic literacy, including singing and dancing (

Mulualem et al. 2022). Contemporary global educators in the present era can also employ embodied literacies.

Trethewey (

1999), writing from Arizona in the United States, links embodied literacies to the concept of disciplined embodiment. Examples of disciplined embodiment, from an academic literacy perspective, are demonstrated in the counseling techniques of psychologists and artefact analysis by archaeologists. Awareness of disciplinary embodiment, particularly through literacies, could assist global educators in decolonizing knowledge.

Tewahedo provides a transformative approach to academic literacy in global education. It equips students to critically examine how history, culture, context, and power shape learning practices—fostering analytical thinkers while ensuring education reflects diverse perspectives. This need for critical awareness aligns with

Cope and Kalantzis’ (

2006) assertion that curricula and pedagogy have long been determined by dominant groups—academics, politicians, and external stakeholders—who institutionalize their ideologies.

Street’s (

2003) critique of the autonomous model of literacy further underscores that reading and writing are never neutral. They are embedded in cultural, political, and ideological power structures (

Street 2003). Contemporary examples include suppression of dissenting voices challenging dominant narratives on campuses globally (

Darian-Smith 2025). By unifying diverse perspectives, Tewahedo enables novice scholars to understand the power structures underlying academic discourses.

This article argues that high-stakes multiple-choice testing in global education—particularly when imposed on Black, African, and Indigenous students—constitutes a colonial practice of power. Such academic literacy assessments demand thorough decolonial resistance through alternative literacy frameworks, such as Tewahedo, which reject these reductive, culturally exclusionary evaluation methods. As in colonial divide-and-rule tactics, despite their perceived benefits, multiple-choice assessments isolate students into unimodal learning (

Sarfraz et al. 2024). This method contrasts with global Indigenous Knowledge Systems, where peer interaction, collaborative learning, and scholarly argumentation, as emphasized in Tewahedo, drive knowledge generation (

Eybers and Dewa 2025). Novice academic literacy students must understand how institutional and historical dynamics sustain multiple-choice testing, a practice inherited from the Global North, which can be used to systemically exclude Indigenous and African epistemologies from assessment paradigms. This consciousness, if nurtured by teachers globally, enables students to decolonize literacies in communal interactions, reading, and writing, with the understanding needed to cement their feelings of growing in and belonging to disciplines.

Tewahedo epistemology centers on Andǝmta (አንድምታ), the Ge’ez term for ancient Ethiopian exegesis (

Alehegne 2022), where communal, multimodal practices of critical textual interpretation, Tergwame (ትርጓሜ), intertwine with explanation. To reiterate, Andǝmta” (አንድምታ), or exegesis, is the collaborative, critical interpretation, and explanation of texts, rooted in communities’ historical, cultural, and linguistic contexts (

Belay 2022). Congruently, Tergwame (ትርጓሜ) refers to the ways that interpretation interplays with explanation. Andǝmta (አንድምታ) embodies a decolonial model of academic literacy, one that disrupts Eurocentric hegemony, including autonomous, generic models, by centering Indigenous epistemes, Indigenous Ethiopian languages, and communal knowledge practices. Like

wa Thiong’o’s (

1986) insistence on linguistic sovereignty, this ancient Ethiopian framework (

Alehegne 2022) transforms academic literacy development into acts of cultural preservation and resistance, in addition to cultural tools for knowledge production. In this view, Andǝmta (አንድምታ) offers global academic literacy practitioners a decolonial framework for designing inclusive, multimodal environments to unify local and disciplinary knowledge systems.

The Sem-ena-Werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ) principle—wax and gold—embodies the decolonial power of Andǝmta (አንድምታ), challenging Eurocentric literacy models by promoting layered modes of meaning-making. As a core tenet of Tewahedo epistemology, it offers Africa and the world a transformative framework for academic literacy: one where knowledge emerges from Ge’ez hermeneutics, communal critique, and the interplay of surface, wax, and depth, gold. Here, decolonial theory intersects critically (

wa Thiong’o 1986). Sem-ena-Werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ) does not merely add Indigenous epistemes to Eurocentric frameworks, but displaces them, insisting that knowledge production arises initially from Ge’ez, or other African languages, and Tewahedo cosmology and communal practice. To summarize, as Africans teach and learn through Andǝmta” (አንድምታ) and Tergwame (ትርጓሜ), Indigenous languages, history, and culture enable them to decolonize Eurocentric constraints and produce gold, which is new knowledge and truth.

Within the Tewahedo framework, exegesis, or Tergwame (ትርጓሜ) in Ge’ez, involves the communal interpretation of written texts and visual and embodied literacies to reveal their original meanings and global relevance. Tergwame (ትርጓሜ) serves as a powerful decolonial strategy by centering Indigenous Ethiopian hermeneutics, rooted in Ge’ez language and communal knowledge transmission, to challenge Eurocentric literacy norms, while modeling how African epistemologies can redefine academic engagement beyond colonial assessment paradigms. Tergwame (ትርጓሜ) interpretive, exegetical approaches mirror multiliteracies theory (

Kelhoffer 2013) by bridging text and context, offering a decolonial framework to transform academic literacy from unimodal to multimodal practices. Practiced for thousands of years in Ethiopia, Tergwame (ትርጓሜ) exemplifies an Indigenous African pedagogic system for fostering community, interaction, and critical interpretation of academic texts—qualities essential for engagement in classrooms worldwide.

Tergwame (ትርጓሜ) serves essential roles in Ethiopian Qeddase (ቅዳሴ) liturgical events, demonstrating multiliteracies through sacred cosmological dialogue—with ancient Ge’ez serving as the core medium for transmitting knowledge and literacies. The Tergwame (ትርጓሜ) episteme, under Tewahedo, is a significant decolonial pedagogy, as per

wa Thiong’o’s (

1986) decolonial theory, as it centers Indigenous languages and knowledge systems, seen in the use of Ge’ez in Qeddase (ቅዳሴ) dialogues. Multimodal elements, such as paintings and material artefacts strategically positioned in sacred spaces, function as cultural semiotics that resist colonial epistemic erasure by preserving Indigenous Knowledge Systems (

Mulualem et al. 2024). The significance of the co-facilitation of Qeddase (ቅዳሴ) by elders and scribes embodies

wa Thiong’o’s (

1986) call for reclaiming cultural autonomy, as it bridges institutional education with local traditions, thus decolonizing knowledge.

Like paintings and diverse material artefacts, Qeddase (ቅዳሴ) events place immense value on the display and interpretation of ancestral, sacred manuscripts as generators of knowledge (

Mulualem et al. 2022). In a decolonial framework, the use of ancestral, sacred manuscripts in Qeddase (ቅዳሴ) events reflects a resistance to epistemic colonialism by centering Indigenous Knowledge Systems. Engaging with Indigenous texts disrupts Eurocentric dominance by centering local texts as primary sources of knowledge production—a decolonial strategy of counter storytelling (

Dutta et al. 2022). Qeddase (ቅዳሴ), reflected in its ancient status, is therefore an original intellectual template for global academic literacy development. If applied with sensitivity, it has the potential to reverberate with students who emerge from Indigenous Knowledge Systems where local languages are used in ancestral ceremonies, through embodied and multimodal practices. As key agents in higher education, academic literacy developers worldwide are uniquely positioned to empower students in reclaiming Indigenous and ancestral epistemes through decolonial counter storytelling (

Dutta et al. 2022)—transforming how knowledge is produced and legitimized.

The liturgical, Qeddase (ቅዳሴ) literacies of Tewahedo, integrating oral, written, visual, performative, and spatial elements, reflect multiliteracies theory (

Cope and Kalantzis 2000;

Cope et al. 2017). They provide valuable insights for academic literacy developers aiming to support and engage students through diverse modes of meaning-making. Similarly, the New London Group outlined five core principles for conceptualizing multiliteracies: cultural and linguistic diversity, contextualized learning, critical engagement, and designing social futures (

Cazden et al. 1996). The decolonial benefit of incorporating multiliteracies principles, such as cultural and linguistic diversity, into pedagogy lies in their ability to challenge colonial epistemologies by valuing IKSs and fostering inclusive educational practices (

Eybers and Dewa 2025). This article examines how Tewahedo aligns with the principles of multiliteracies, offering a model that can decolonize academic literacy facilitation and design social futures that value the Indigenous cultural systems students bring to disciplines globally (see

Table 1 below).

Mirroring

wa Thiong’o’s (

1986) decolonial principles,

Cazden et al. (

1996) emphasize cultural and linguistic diversity as foundational principles of multiliteracies theory, noting that learners’ unique backgrounds influence how they develop disciplinary identities. Here, different communities create knowledge through their own literacy practices, showing that knowledge varies across cultures. Tewahedo’s expansion beyond Ge’ez into languages like Amharic, Tigrinya, and Oromo demonstrates its adaptability to global disciplinary contexts, offering a model for how multiliteracies can help academic literacy facilitators decolonize literacies and support students’ knowledge creation. The Tewahedo framework is adaptable to different epistemic settings, enabling literacy facilitators to incorporate local and disciplinary epistemologies, discourses, and practices—in ways familiar to communities and students. By embracing Tewahedo praxis, educators can foster critical thinking and literacy skills while affirming Indigenous students’ identities and cultural heritage, a value that is central to

wa Thiong’o’s (

1986) decolonial paradigm.

Concerns About the Dominant Pedagogic System

Contrary to

Sebolai (

2014) colonial validation of multiple-choice assessments, global attrition rates reveal how technical literacy models—by erasing cultural dimensions of learning—actively alienate scholars, proving the need for decolonial alternatives.

Street (

2003), along with others, including

Gee (

2015), critiques technical models, arguing that in diverse global contexts, literacies have always been shaped by the diverse social, cultural, metaphysical, and physical needs of communities. Consequently, while it is important to acknowledge mechanistic, neutral, technical, and disciplinarily decontextualized constructs of literacy, it is equally pertinent to recognize sociocultural theories of literacies, particularly those that highlight the impact of students’ and institutional power relations on academic development (

Lillis and Scott 2007). Understanding academic literacy as a situated, context-dependent phenomenon allows for inclusive, decolonial pedagogical methods that address the specific needs of novice scholars across the globe (

Jojo 2024).

Street’s ideological model of literacy, along with multiliteracies theory (

Cope et al. 2017), emphasizes the integration of diverse modes of meaning-making within disciplinary and social contexts. For example, students’ need for academic literacy mastery does not end after the first year. In Tewahedo cultures, literacy development was embedded across disciplines and multiple levels of study. In stark contrast, autonomous and technical literacy models, championed by

Sebolai (

2014) and

Weideman (

2021), were forcefully imposed on Indigenous and African communities during colonialism and apartheid in South Africa. In this context, the discriminatory ICELDA TALL tests exemplify a profound misconception, framing academic literacy as a neutral set of decontextualized skills. This approach, adopted by academic literacy units across South Africa, fails to acknowledge the deeply embedded social practices that operate across knowledge systems, cultures, and disciplines, perpetuating systemic inequities through marginalizing Indigenous epistemes. Consequently, autonomous literacy models have been critiqued for their application in marginalizing African and diverse cultural epistemologies, limiting their participation in creating and disseminating knowledge (

Lillis and Scott 2007).

5. Findings

The article by

Mlotshwa and Tsakeni (

2024), “Exploring Indigenous Knowledge Systems Integrated in Natural Sciences Practical Work in Selected South African Schools”, presents compelling evidence of the pedagogical benefits of integrating Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKSs), including Tewahedo epistemology, into global education, particularly academic literacy development. This study demonstrates how integrating Indigenous epistemes, such as Andǝmta (አንድምታ) traditions, including Tergwame (ትርጓሜ), and communal interpretation and explanation with scientific inquiry fosters a richer, more inclusive learning environment, aligning with

wa Thiong’o’s (

1986) theory that language and cultural identity are central to reclaiming knowledge systems and resisting colonial narratives.

By focusing on plant genetic variation, animal behavior, moon cycles, and agricultural practices,

Mlotshwa and Tsakeni (

2024) demonstrate how IKSs enhance students’ engagement with and understanding of complex scientific concepts, while fostering critical thinking and disciplinary identity (

Mlotshwa and Tsakeni 2024). Their application of Tergwame (ትርጓሜ)—Tewahedo’s (ተዋሕዶ) interpretive exegesis—reveals how cultural narratives serve dual educational purposes. Far from mere intellectual analysis, this interpretative tradition actively bridges cultural and disciplinary literacies, embedding shared truths within collective learning (

Mlotshwa and Tsakeni 2024).

This method, as demonstrated in the study by

Mlotshwa and Tsakeni (

2024), empowers learners to critically engage with both scientific and cultural knowledge, deepening their understanding of how these systems have historically intersected in pre-colonial, social, and educational contexts. Such an approach also enables African academic literacy developers and students to analyze the strategies colonialism used to disrupt Indigenous modes of knowledge production and exploit them for Global North economic development. For instance, ancient Ethiopian manuscripts, including versions of The Book of Enoch and The Kebra Negast, were looted by Europeans during the colonial era, and are now housed in museums and archives throughout the Global North. This historical context underscores the importance of the Tewahedo model today, as it highlights the importance of restoring and integrating Indigenous epistemologies into contemporary education systems, fostering decolonized, inclusive academic literacy practices globally.

McKnight’s (

2015) study further underscores the benefits of integrating IKSs into international STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education. Instructors who participated in them emphasize how IKSs enable them to build on learners’ pre-existing knowledge, making science more meaningful and accessible (

McKnight 2015). This method aligns with the Tewahedo epistemology, which views knowledge as deeply rooted in communal needs. For example, one educator highlighted how teaching disease treatment through IKSs enriches inquiry by incorporating culturally relevant practices (

McKnight 2015). To illustrate, teachers contextualized bacteriology by discussing traditional beer production in local contexts, demonstrating how real-world applications rooted in students’ lived experiences deepen understanding and engagement (

McKnight 2015). These methods resonate with the Tewahedo emphasis on integrating diverse literacies to create knowledge holistically and interactively.

The participants of McKnight’s study indicated that dialogues, as embedded in Qeddase (liturgy), are central to integrating IKSs into the science classroom. One of the teachers remarked, “I initiate the discussion by asking a few leading questions […] which gives me [students’] input of how certain things are in their culture” (

McKnight 2015, p. 119). These dialogic approaches reflect

Cope and Kalantzis’ (

2000) emphasis on “situated practice”, where learners’ cultural knowledges are valued as meaning-making resources (see

Jojo 2024). In this approach, dialogic epistemes within STEM resonate with a construct of academic literacy as a “social practice” (

Lillis and Scott 2007). This communal method mirrors Tewahedo epistemology, where multiliteracies enable shared interpretation and play a leading role in meaning-making. Noticeably decolonized, communal pedagogies differ from multiple-choice assessments that separate students from their peers, families, and communities.

The benefits of IKSs, including Tewahedo principles, extend beyond STEM to Humanities disciplines, where their integration serves as a decolonial strategy to address epistemic exclusion in African and global universities. A central principle of disciplinary decoloniality is multilingualism.

Mkhize and Ndimande-Hlongwa (

2014), echoing

wa Thiong’o (

1986), argue that embedding IKSs into the Humanities curriculum challenges the marginalization of African knowledge systems, while cultivating an inclusive learning environment where diverse linguistic and cultural traditions thrive. Similarly,

Cakata (

2023), also mirroring

wa Thiong’o’s (

1986) decolonial praxis, illustrates how incorporating Sesotho, isiZulu, and isiXhosa into the psychology curriculum reshapes and Africanizes disciplinary discourses.

These languages, as carriers of Ubuntu—an ethic emphasizing interconnectedness and community, akin to Tewahedo—enable educators to transcend the limitations of technical and autonomous academic literacy models, inherited during colonialism, by fostering collaboration among diverse actors. This multilingual approach not only democratizes access to disciplinary knowledge but also deepens critical engagement, empowering scholars to synthesize their linguistic heritages into personal ways of knowing.

Mahlangu and Garutsa’s (

2019) transdisciplinary course at Fort Hare University is an example of the successful integration of Ubuntu, academic literacy, multilingual education, and community agency.

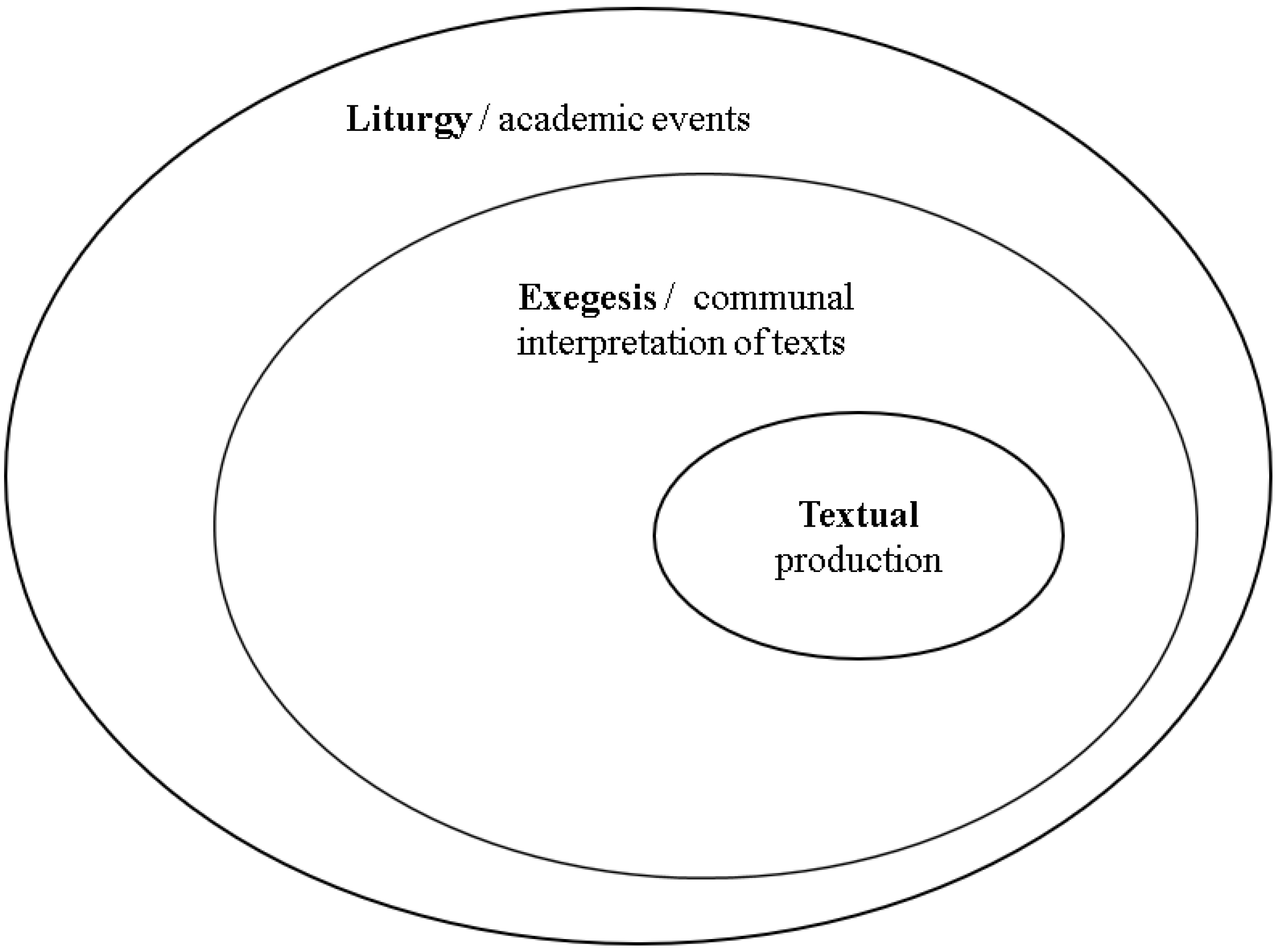

The Tewahedo academic literacy ontology, as illustrated in

Figure 2, provides a blueprint for understanding how Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKSs) can enhance and diversify the ways novice scholars acquire disciplinary literacies in universities throughout the globe. According to

Mulualem et al. (

2022), Ethiopia’s Indigenous pedagogic systems have fulfilled a vital role in preserving the nation’s history, cultures, and generations of writers. After all, Ethiopia was the only African nation to not be colonized by Europe. However, the authors observe that scribes originally constituted an elite sector of society (

Mulualem et al. 2022). Despite this exclusivity, Ethiopian scribes were instrumental in preserving liturgical events through Andǝmta (አንድምታ), communal interpretation, and Tergwame (ትርጓሜ) explanation, weaving cultural literacies into knowledge production, ensuring local communities’ resilience.

Another Ethiopian episteme, similar to the wax and gold philosophy, stems from

Qiné (ቅኔ) literacies. In this tradition, language is described as lissan, providing a connection between wax and gold (

Mennasemay 2014). From a Western analytical dualistic perspective, reflected in neutral, technical literacy models advocated by

Sebolai (

2014), this view can be seen as ontological dualism. Ontological dualism is a belief in the separation of body and mind, or physical and non-physical. However, the author argues that from a Tewahedo unifying perspective, language (lissan) allows both the speaker and listener to grasp the multiple layers of meaning and knowledge, referred to as ‘wax and gold’. This African concept suggests that Tewahedo multiliteracies can convey both obvious (wax) and hidden (gold) meanings simultaneously (

Mennasemay 2014). Adopting the

Qiné (ቅኔ) method in academic literacy development can function as a decolonial strategy to counter epistemic marginalization as experienced by students taking the ICELDA TALL tests, fostering a deeper, Indigenous, and interconnected understanding of knowledge production across diverse disciplines.

Cakata’s (

2023) study underscores the transformative potential of integrating Indigenous languages, such as Sesotho, isiZulu, and isiXhosa, into the psychology curriculum, positioning them as carriers of IKSs. Beyond mere translation,

Cakata (

2023) demonstrates that African languages serve as vital tools for exegesis, enabling scholars to engage meaningfully with disciplinary texts, while challenging colonial modes of interpretation, such as the Socratic method. Indigenous languages are portals into African peoples’ cosmologies, offering insights into their worldviews, reviving ancestral modes of safeguarding communities (

Cakata 2023). In this way, African languages humanize Indigenous epistemologies in post-colonial psychology fields, countering Western marginalization (

Chiramba and Nyoni 2024).

6. Discussion

This study highlights the transformative potential of Tewahedo epistemology in redefining academic literacy within African and global higher education. Unlike culturally sterile, decontextualized skills-based models inherited from the West, Tewahedo provides a holistic, community-rooted, and culturally relevant framework that stimulates deep engagement, intellectual agency, and academic belonging (

Nywonsike and Onyije 2011). A central argument in this discussion is that colonial disruptions to Africa’s Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKSs), including Tewahedo’s principles of unity, exegetical practices, and liturgical traditions, have left a lasting impact on how academic literacy is shaped today. Consequently,

Osiesi and Blignaut (

2025) advocate for humanized, decolonized assessments to counter practices that devalue Indigenous epistemes during students’ evaluations.

As higher education institutions across the globe strive to decolonize pedagogy, there is a growing recognition among educators of the need for an alternative literacy model rooted in formerly marginalized epistemologies, while also engaging global frameworks (

Jojo 2024). This model should leverage the culture and agency of Africans on the continent and those of the African Diaspora, promoting the African Renaissance. Integrating Global Citizenship Education principles through academic literacies (see

Eybers and Muller (

2024) into Tewahedo-based frameworks is crucial.

de Andreotti (

2014) argues that critical, questioning literacies are essential for fostering Global Citizenship Education that interrogates colonial influences on international relationships.

It is necessary to consider counterarguments and potential resistance to Tewahedo’s unifying framework in higher education. After all, the West’s and even some African leaders’ marginalization of Tewahedo principles in African educational systems remains a systemic strategy of devaluing Indigenous Knowledge Systems in educational systems to maintain power (

Eybers 2020).

Fanon (

1952), in

Black Skin, White Masks, highlights how coloniality leads to internalized oppression, where Indigenous people globally judge their identities, knowledge, and cultures according to racist standards. Therefore, it is necessary to acknowledge that even in regions where Indigenous people have gained greater influence, like Africa, some actors still employ colonial methods in academic literacy development, potentially exacerbating the crisis of student attrition in higher education.

Today, numerous African and global universities are making concerted efforts to decolonize education, aiming to challenge and transform historically Eurocentric paradigms. In Ethiopia,

Merawi (

2024) emphasizes that overcoming Eurocentrism necessitates scholarly methods that synthesize ancient and modern historical perspectives, fostering a more inclusive, Indigenous understanding of knowledge. Academic literacies fulfil a critical role in this process. Decolonized academic literacy development requires Indigenous people worldwide to elevate their languages and cultures in critical discussions, as through Tergwame (ትርጓሜ), integrating them into the creation of new knowledge to challenge colonial narratives, as theorized by

wa Thiong’o (

1986). Furthermore, there is growing recognition that achieving truly decolonized education demands the development of alternative literacy models rooted in African epistemologies and Indigenous frameworks (

Eybers and Dewa 2025), ultimately reshaping the foundations of learning and knowledge production.

It is necessary to acknowledge that the vision of decolonized academic literacy teaching, learning, and assessment methods remains undermined, not only by colonial and apartheid legacies but also by the actions of Africans themselves. ICELDA assessments—championed by African scholars such as

Sebolai (

2014)—enforce rigid colonial language standards by requiring unimodal testing exclusively in Afrikaans and English at South African universities. By privileging monolingual questions in European languages, unimodal, and ostensibly standardized modes like multiple-choice, these tests prevent Indigenous, multilingual students from interpreting knowledge through Indigenous epistemes, including Andǝmta (አንድምታ) and Tergwame (ትርጓሜ).

The matter of ostensibly standardized academic literacy tests warrants closer examination, particularly in global and decolonial contexts where educational advancement is directly connected to Indigenous students’ aspirations to improve and safeguard the wellbeing of their families and communities. While reliable assessments are necessary, it is important to acknowledge the roles of literacy tests, such as ICELDA tests, in marginalizing African and other vulnerable cultural groups within disciplines dominated by Eurocentric testing practices.

Leibowitz’s (

1969) seminal study exposes how United States literacy tests were strategically used to delay the admission of African Diaspora students and students of color into segregated universities, aligning with

Street’s (

2003) ideological model, where literacies are manipulated to exclude and include. In South Africa, the introduction of ICELDA tests alongside rising African student enrolments in historically white universities raises concerns about the adoption of Eurocentric ideologies in literacy assessment by Black and African educators.

Goldman’s (

2004) analysis of the disproportionate impact of literacy tests on felons in the United States demonstrates how such assessments have historically been wielded as instruments of control by influential collectives. Likewise, in the South African academic context, technical and seemingly neutral constructs of literacy that warrant culturally exclusive literacy tests, such as ICELDA tests, while denying opportunities to engage in Andǝmta (አንድምታ) and communal Tergwame (ትርጓሜ), may function as gatekeeping mechanisms, reinforcing inequalities as during the era of apartheid and Bantu (mis)education. In stark contrast, Tewahedo epistemic traditions, rooted in communal learning, multiliteracies, and exegetical hermeneutics, offer an Indigenous model centered on belonging, shared growth, and collective advancement (

Mulualem et al. 2024). These Indigenous Knowledge Systems challenge divisive frameworks rooted in ontological dualism, which perpetuate discrimination. Instead, they offer pathways to promote unity and epistemic inclusion in universities throughout the globe.

Cakata (

2023, p. 44) highlights how the introduction of Western norms into academic literacy testing, possibly echoed in the ideology underpinning ICELDA tests, alongside the imposition of European languages, was deliberately employed to erase Indigenous languages and “re-create a new human [or slave]” in service of colonialism. Alarmingly, similar concerns over discriminatory literacy and language pedagogies continue to surface in the Global North (

Clements and Petray 2021). In contrast, Tewahedo-based epistemes provide a powerful method for unifying Indigenous students with communal knowledge systems and languages, by fostering deeper engagement and a reclamation of epistemic agency and sovereignty through Andǝmta (አንድምታ) and Tergwame (ትርጓሜ).

Another key challenge in global academic literacy courses is the disconnect between IKSs and formal disciplines. This study highlights the importance of bridging these epistemologies to enhance students’ success, intellectual engagement, including critical thinking, and cultural affirmation within disciplines (

Mlotshwa and Tsakeni 2024;

McKnight 2015). Explicitly linking IKSs to global disciplines deconstructs the colonial invention that Indigenous cultures, knowledge systems, and “people have no worthy knowledge from which to draw” (

Cakata 2023, p. 46).