Abstract

In the first decades of the 20th century, the Sámi movement developed a vision for how education could play a central role in the future of the Sámi people. Faced with expanding colonial school systems, teachers and intellectuals imagined what education could look like if it was to contribute to the flourishing of Sámi livelihoods. One key contributor to this project was Per Pavelsen Fokstad (1890–1973). This article outlines key elements in Fokstad’s philosophy of education and discusses his contribution to education theory in both his contemporary cultural interface and the one that we work in over 100 years later. The analyses are based on a hermeneutical reading of Fokstad’s published texts. The analyses show how Fokstad outlined a philosophy of education based in the mother tongue as a catalyst for the child’s development of a sense of self, a feeling of community, and a connection to land. This philosophy was revolutionary in his own time due to its redefinition of what was worth learning and knowing, and has grown in significance since.

1. Introduction

Decolonizing education is a project that relies on tracing the paths towards different futures that have become overgrown and barely visible due to the dominance of colonial institutional practice and thought. While the field of Sámi and indigenous philosophy of education is expanding, its intellectual history is rarely traced back through the rough sea of assimilatory and nationalist school policy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Keskitalo 2022; Olsen and Sollid 2022). However, Sámi research that emerged from the 1970s onwards was premised on the intellectual work of the early Sámi movement, which articulated how education could become a part of a self-determined Sámi future at the very beginning of the century (Kortekangas 2021). Activists and organizers of the early Sámi movement, including Elsa Laula Renberg (1877–1931), Isak Saba (1875–1921), Anders Larsen (1870–1949), Karin Stenberg (1884–1969), and Per Pavelsen Fokstad (1890–1973), also articulated keen theoretical insights into the purpose and possible futures of indigenous education, which are largely unrecognized in the contemporary literature (Svendsen 2021).

In this essay, I outline a decolonizing future for education that was imagined by Sámi philosopher and teacher Per Pavelsen Fokstad. In published works from 1917 up until his death in 1973, Fokstad offered a vision for education that articulated the fundamental values and knowledges of a Sámi worldview with the promise of equal rights to education for all children. He outlined a hopeful view of how institutionalized education could fuel the flourishing of the Sámi people. Although Fokstad is known for his political contributions to Sámi self-determination (Zakariassen 2012), he has not been studied as a philosopher and theorist of education. Bringing him into this literature is a contribution to building our intellectual sense of ancestry (Porsanger and Seurujärvi-Kari 2021). Working with the concept of máttut, or ancestor, Porsanger and Seurujärvi-Kari argue that tracing Sámi intellectual history beyond the institutionalization of Sámi research provides a stronger foothold for present-day efforts to build Sámi knowledge (Porsanger and Seurujärvi-Kari 2021). Per Fokstad’s work is particularly fitting for this project, as it was precisely the institutionalization of Sámi education that his lifework contributed to realizing.

Per Pavelsen Fokstad (1890–1973) was a teacher, intellectual, and politician from Deatnu (Hætta 1999). In addition to serving a lifetime as a teacher, he served as mayor in Deatnu both before and after World War II, and he worked tirelessly for the establishment of Sámi educational institutions and policies for Sámi self-determination (Andresen et al. 2021). Fokstad wrote a comprehensive curriculum for Sámi education in 1924, in the form that the Norwegian curricula took at the time. The form had a purpose; the Norwegian parliament had commissioned the preparation of a revision of the entire Norwegian school system in order to improve it as a comprehensive system for all (Den parlamentariske skolekommisjon 1926, pp. 18–49). Fokstad’s proposed curriculum was published as part of the committee’s report in 1926, with a majority verdict that it would not be feasible nor appropriate to implement due to its reliance on Sámi language and culture. The majority of the committee’s reasoning was informed by racist evolutionism, and commented that “knowledge of Sámi does not open the mind to a higher culture, that can compensate for the what the child would lose with a lesser proficiency in the Norwegian language” (Den parlamentariske skolekommisjon 1926, p. 116). Much has been written about the dismissal of Fokstad’s work, more than about the merit of his curriculum (Eriksen and Niemi 1981; Jensen 2015; Kortekangas 2021; Minde 2005; Zakariassen 2012). The curriculum is a keystone in the articulation of the Sámi movements’ demands for education in the early 20th century. Fokstad’s contributions to education policy was also valued by Norwegian authorities, however. He was part of the postwar Sámi commission, the national school commission, and most other initiatives to promote Sámi education in the postwar era (Hætta 1999). When he died in 1973, the Nordic Sámi Institute he worked so hard to establish had been realized as the first institution for Sámi research (Porsanger 2011).

The work I present here is based on a hermeneutical close reading of Fokstad’s published texts. My main focus is discerning the philosophical and pedagogical contents of Fokstad’s essays and school plans, meaning how these texts express ideas about what is true, what is good, and what is important and how education can promote these values. I trace his ideas both to his contemporary references and inspirations and to recent work in indigenous education. The main ambition of this article is to develop a re-articulation of Fokstad’s educational philosophy that can make his contribution to indigenous education find new readers, a century after he first put them into writing. In the following, I will outline Per Fokstad’s own context of education theory.

1.1. Per Fokstad’s Philosophical and Political Context

Per Fokstad’s ideas about education played a central part in public discourse about Sámi education from his first publication, “How Norwegianization in the primary school interfered in my life”, in 1917. The essay was part of a collection edited by Lars Otterbech and Johannes Hidle named Fornorskingen i Finnmarken (Norwegianization in Finnmark) (Otterbech and Hidle 1917). The volume articulated a frontal attack on Norwegian school policy and practice in Sámi areas, with Sámi political and pedagogical pioneer Anders Larsen (1870–1949) and Per Fokstad as key contributors. The volume was controversial, and engendered 2–300 contemporary opinion articles (H. Dahl 1957). As the recent report from the Norwegian Truth and Reconciliation Commission also shows, there was considerable debate and doubt over education policy in Sámi and Kvæn areas in the formative decades of the Norwegian public school system, and forced assimilation (Norwegianization) was only one of several political avenues that were explored at the time (Sannhets- og forsoningskommisjonen 2023). Per Fokstad was a strong voice in these debates and would remain central in them throughout his life.

Fokstad’s educational ethos was remarkably consistent, and his key ideas are evident in his 1917 essay. He introduced the idea of cultural and linguistic plurality as a foundation for education (Eriksen and Niemi 1981), as well as ideas about the role of the mother tongue, love, spontaneity, and community in education. His philosophical formation had been influenced by his studies abroad in Denmark at Askov Peoples’ High School (1915/16), where he was schooled in the educational philosophy of N. F. S. Grundtvig (1783–1872), and greatly inspired by his thoughts on the role of the mother tongue in education (Hætta 1999). Fokstad spent the 1919–20 academic year at Woodbrooke College in Birmingham, UK, where he expanded and developed his ideas about Sámi moral philosophy and religion in dialogue with the Quaker academic community he found there (Jensen 2015).

Fokstad’s most significant philosophical influence, however, was the French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859–1941). Immensely influential in his time, Bergson was something of an academic superstar in and beyond the community Fokstad visited in Paris during the 1919/20 academic year (Sinclair 2020). Fokstad read Bergson’s work widely and deeply and incorporated a variety of Bergsonian vitalism in his own philosophical project. The Bergsonian stream in Fokstad’s philosophy adds a complexity that made him difficult to read, both for his contemporaries and scholars who have tried to interpret him since. As his academic friends have pointed out, Fokstad was not only politically controversial in the Norwegian administration on all levels; he was also seen as an original with a somewhat tangential connection with reality by some of his Sámi local contemporaries (T. E. Dahl 1970; Gjessing 1973).

The final strand in Fokstad’s philosophical thinking is by far the most important, but could not be referenced as an academic tradition in his time. Articulating Sámi ideas about what is true, what is good, and what is important, that is, outlining Sámi philosophy and therefore guidance in life, was Fokstad’s lifetime project. In present-day Sámi scholarship, this work can be read as a form of documentation and development of árbediehtu (Porsanger and Guttorm 2011). Jelena Porsanger writes that “Árbediehtu is the collective wisdom, practical skills and theoretical competence evolved and acquired by Sami people through centuries in order to subsist economically, socially and spiritually” (Porsanger 2011, p. 242). Fokstad’s concern was to convey the árbediehtu of spiritual subsistence, and he found it exceedingly difficult. His Sámi language to develop truly Sámi thinking was already impoverished by Norwegianization the way he saw it, and the Norwegian language he worked in to communicate with his peers lacked the words he needed to express his true meaning (T. E. Dahl 1970). The art that could gesture at the heart of the Sámi spirit was sparse in his eyes, but he did work extensively with contemporary artists such as John Savio, Nils Skum, and the writer Matti Aikio (U. Fokstad 2017). The culturally genuine social practices were also harmed, he thought, but still the Sámi spirit could be studied. He used what he felt were already remnants of Sámi culture to study and articulate his ideas about what the spirit of the Sámi aspired to throughout his lifetime.

1.2. Fokstad’s Philosophy in the Historical and Pedagogical Literature

Fokstad’s work has primarily been studied by historians in the academic context of political history (Zakariassen 2012). Knut Einar Eriksen and Einar Niemi highlighted in their comprehensive historical analysis of minority policy in the north between 1860 and 1940 that Fokstad’s thinking about education was potentially revolutionizing for education in and beyond Sápmi (Eriksen and Niemi 1981). Their analysis shows how Fokstad’s contribution was crucial for introducing the idea, and indeed possibility, of cultural pluralism into the public discourse about education (Eriksen and Niemi 1981, pp. 272–73). This topic has been further developed and discussed in historian Ketil Zakariassen’s substantial treatment of Per Fokstad’s political work. Zakariassen analyses Fokstad’s work in light of his contemporary Norwegian academic environment. He explains how Fokstad’s ideas about fostering and growing a national spirit reflected a key theme in Norwegian pedagogical discourse in his time (Zakariassen 2012).

Drawing on Otso Kortekangas’ contribution on Sámi education history in the Nordics between 1900 and 1940 (Kortekangas 2021), it can be argued that Zakariassen also overstates Fokstad’s intellectual affiliation with contemporary Norwegian pedagogy at the expense of an emerging pan-Sámi articulation of Sámi thinking about education. Kortekangas’ analysis shows the interconnections between Fokstad’s work in the Norwegian context and the articulations of Sámi educational projects in other national contexts. This contribution helps to articulate Fokstad´s contribution in the context of his contemporary Sámi movement, which is helpful for highlighting the Sáminess of his educational philosophy.

As Jukka Nyyssönen has noted about education history on the Finnish side of Sápmi, historians have been less interested in the philosophical aspects of education history than scholars in Sámi and indigenous education (Nyyssönen 2018). While this is also the case on the Norwegian side, Lund (2003) has combined careful empirical work that includes Fokstad’s contributions with forward-looking and policy-oriented analyses of Sámi education history in Norway. Lund has convincingly argued that the Sámi curriculum in practice only has been realized insofar as it did not challenge the existing power relations in Norwegian education (Lund 2003). Fokstad himself experienced an abyssal distance between what Norwegian intellectuals, officials, and politicians would agree with in theory and the practice they pursued (U. Fokstad 2017). This theme has been further developed in Kaisa Kemi Gjerpe’s work on the Sámi curriculum in Norway, where she argues that the Sámi curriculum implemented has been drained of Sámi content to the extent that it amounts to a merely “symbolic commitment” by the state (Kemi Gjerpe 2017).

The existing literature on Fokstad’s work forms a foundation for a deeper investigation of his philosophy of education, in particular in relation to key themes in contemporary Sámi educational philosophy. Asta Balto explains how articulating Sámi philosophies of education entails both expressing a Sámi ontology, or life-world, and a Sámi epistemology, meaning a theory of knowledge (Balto 2005). Ole-Henrik Magga has similarly outlined how the project of indigenous education should be based in indigenous languages, indigenous land, and indigenous cultures in order to provide a basis for learning for indigenous children (Magga 2005). These ideas resonate strongly with Fokstad’s educational philosophy. The analyses below outline the ideas that Fokstad´s essays and proposed curriculum convey about how education can contribute to self-determination and strength in both Sámi children and the Sámi people.

1.3. Material and Methods

The method I use in these analyses is a hermeneutical close reading of Fokstad’s published texts. The hermeneutical reading is informed by the intertextual landscape of Fokstad’s texts that I outline above, but also by biographical work that has brought attention to some of the more personal parts of his work, including his letters (Hætta 1999; Jensen 2015). His daughter Unni Schøn Fokstad´s biography of her father from 2017 contains excerpts from letters in the family archive (not made publicly available) that can inform his published texts (U. Fokstad 2017). The contributions about Fokstad’s work in the Sámi school history shed light on how he was able to work with his ideas in his everyday life as a teacher in Sámi schools (Ravna 2007). I have also drawn on published interviews and commentary (T. E. Dahl 1970; Gjessing 1973).

The core archive I base these analyses on is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Empirical material.

These texts were written by Fokstad in Norwegian, mostly for a Norwegian academic and bureaucratic audience. All English-language translations in this article are my own. The texts seek to explain and flesh out the purpose and necessity of Sámi education in the Norwegian context. The two postwar essays written for Sámi contexts (P. Fokstad 1957, 1967) are more speculative and show how Fokstad worked through articulating possibilities of interpretation of Sámi culture.

As noted above, I read Fokstad’s texts as articulations of Sámi árbediehtu, and this means that my analyses are also bound by the ethical demands of working with traditional knowledge (Jonsson 2011). In a hermeneutic frame, this ethical commitment can be seen as a commitment to honoring the philosophical tradition that Fokstad wrote in, despite there being very few texts available to inform that knowledge. My frame of interpretation for Fokstad’s Sámi árbediehtu is shaped by the generation who worked with it between his time and ours. In this generation, the work of Alf Isak Keskitalo, Asta Balto, Ole-Henrik Magga, and other Sámi academic pioneers has been crucial for shaping the Sámi philosophical tradition in writing (Porsanger 2011). Like Fokstad, they also worked and thought in a cultural interface (Nakata 2007) in which they articulated Sámi árbediehtu with other philosophical traditions, and so do we. Tradition is received in time and space (Gadamer 2013), and hermeneutical engagement is an event that articulates the work as it appears here and now, with attention to the routes it took to come here and the possible paths forward. In the following, I read Fokstad in relation his place in tradition and my own as a contemporary scholar in Sámi and indigenous education.

2. Analyses

2.1. On Love, Land, Nation, and the Mother Tongue

In the essay “How Norwegianization interfered in my life” from 1917, Per Fokstad published his first notes towards a Sámi educational philosophy (P. Fokstad 1917). The problem with Norwegianization, he explained, was that it hindered Sámi children’s spontaneous and intuitive expression of the self through preventing them from using their mother tongue. The concepts of love, the mother tongue, and spontaneity were central to Fokstad’s thinking. These themes were developed from both his experience and observations of learning in the mother–child relation and his experience and observations of the failure to learn in a colonial school. He wrote the following:

Fokstad argued that the Norwegian teacher could not reach the Sámi child because they did not share a language of spontaneous expression. He contrasts the distant and cold pedagogical acts of the Norwegian teacher with those of the mother, who brings language to life and gives meaning to letters. The mother tongue invites the child into its significant relationships, names its bonds and its life world. In Fokstad’s thinking, the mother tongue is the connection that is forged between the child’s inner life, its feelings, and the world.Only with the help of the mother tongue could one’s interest awake. By that one could get the child’s feelings into words. For feeling is the door to sense and will in any human being. Only for the warm and the good would one open up, and the warmth is felt in the mother tongue.(P. Fokstad 1917, p. 39)

The notion that feelings are at the heart of any learning process was central for Fokstad. He did not accept the division between feeling and thinking that was already well established in modern culture at his time. Fokstad thought of mind and body as contingent, and feelings were primary. He had strong support in the contemporary pedagogical literature. William James, for one, complained about the futility of an education that did not enlist the bodily instincts, especially the most paramount feelings that he saw as fear, love, and curiosity (James 1899). James and other anglophone authors did not theorize the role of the mother tongue in this process, however. The identification of the mother tongue as the central mediator in the child’s learning process, the medium that connects the child with both its relational and natural surroundings, marked a point of departure that would take his philosophy of education beyond the modern colonial civilizing project.

For Fokstad, Norwegian education in the early 20th century amounted to a destructive objectification of the child’s bodily experience of the world. The steps in this process were breaking down the budding vocabulary for the child’s life world and feelings, and the significant relationships that were needed to develop a sense of self in community. He describes this process of isolation in its linguistic, emotional, physical, and cognitive dimensions in the following quote:

Something revolutionary occurred in the emotional life. The bright, forward openness left; the childlike mirth disappeared. One dear not ask about anything; one only guessed. Never did an expression of wonder escape one’s lips. It was as if one suddenly had grown old. One became mute. And gripped by a feeling of loneliness.(P. Fokstad 1917, p. 39)

In this quote, Fokstad describes how a school that rejects children’s spontaneous expression is likely to harm their development of a sense of self, which also necessitates a sense of community. In his description, the child is bereaved of its agency, and made a mute object without the capacity for thinking or engaging in the world. For Fokstad, the denial of the chance to express oneself severed the ties between the self and the world in ways that instilled an existential doubt in the child about whether one would ever be heard or understood.

Fokstad’s analyses of how Norwegianization as education harmed the child highlights another keystone in his thinking about education. For Fokstad, self-expression, which is any expression of will or intention, has a felt motivation in the self, and can only be expressed in relation to others. Self-expression, then, is both affective and collective in nature. This is a point he keeps returning to in his work, articulated in different ways. Late in life, in an interview with Tor Edvin Dahl, he says “Do you understand this? (…) I cannot speak in the ordinary way. I need understanding. I need to know that one is on my side, else I cannot muster the energy to speak” (Fokstad cited in T. E. Dahl 1970, p. 14). I read the carefulness he articulated here as the lifelong effect of the emotional revolution of his schooling. When the social space for expression has been denied early in life, one ceases to presume its existence. The self grows guarded, careful, and doubtful of the capacity of others to meet and harbor its feelings and thoughts. He likened this state of the self to being frozen: “We are frozen to the core. We feel like we should have been laying in the ice. We cannot be ourselves. We must act, pretend, become false” (Fokstad in T. E. Dahl 1970, p. 14).

The education for pretense could only lead to destruction of the self in Fokstad’s eyes, because the child who lost the connection to their feelings would also lose their moral compass. He articulated these effects in many of his essays. In the 1923 essay “Sámi thoughts and demands”, he wrote that the “language tyranny” of the Norwegian school would lead to the loss of “self control and balance that is so necessary in life; they will miss the safe, conclusive valuation of life” (P. Fokstad 1923, p. 122). Fokstad’s analysis suggests that the valuation of the self (life) is conditioned on the child’s own experience of valuation. This experience of valuation relies on the child’s feelings being recognized and acknowledged, and this is impossible without the mother tongue. This theme was not abstract for Fokstad. He had his own struggles with mental health, and so did his son (U. Fokstad 2017). Fokstad was no stranger to applying his intellectual work to his personal life. He thought that his own choice of bringing up his children between two cultures, neither fully Norwegian nor Sámi, without a Sámi language to anchor them, had contributed to his son’s struggles (U. Fokstad 2017).

In his 1923 essay “Sámi thoughts and demands”, he concluded with the dim words “the Sámi will never become Norwegian. But they can perish” (P. Fokstad 1923, p. 130). The threat of perishing that he articulates is not metaphorical, and has at least two references. One is the damage that Norwegianization does to the individual, particularly regarding mental health. Fokstad argued that Norwegianization threatened the very will to live in Sámi subjected to it. The other reference is the livelihood of Sámi as a people, or a nation. In the essay “Some remarks about the Sámi problem seen from within” (P. Fokstad 1967), he seeks to define his concept of nation:

Fokstad’s language in this definition suggests that it can be helpful to read him alongside his philosophical inspiration, Henri Bergson. Bergson makes a foundational distinction between matter and life that can also be traced in Fokstad’s writing. Importantly, this is not a body/mind or nature/culture dualism. On the contrary, the origin of matter and life are the same for Bergson, who writes the following:It is something that is like a force of nature. It can live latently in every people. (…) It is the inner core of personality in the national individual. It is the source of human vitality. We think it is our inner eye, it is our heartbeat and our spiritual breath. It creates and deepens the spirit of the community. In this national community the Sámi individual finds its comfort, and its character is strengthened.(P. Fokstad 1967, pp. 48–49)

The task of philosophy for Bergson is to build the human capacity for becoming “creators of ourselves” for everyone (Ansell Pearson 2018, p. 156). Fokstad echoed the sentiment, but he added the concept of nation, which I understand as a community within language and land, as a condition for intuition. Thinking about the purpose of education, Fokstad underlines the role of the nation in building strength of character in the individual. This also echoes a Bergsonian sentiment. Bergson wrote that connecting with life through intuition will bring “greater strength, for we shall feel we are participating, creators of ourselves, in the great work of creation which is the origin of all things and which goes on before our eyes” (Bergson quoted in Ansell Pearson 2018, p. 156).The matter and life that fill the world are equally within us; the forces which work in all things we feel within ourselves; whatever may be the inner essence of what is and what is done, we are of that essence. Let us then go down into our inner selves: the deeper the point we touch, the stronger will be the thrust which sends us back to the surface.(Bergson quoted in Ansell Pearson 2018, p. 167)

It was not only the child’s development of a coherent self that was at stake in the language question for Fokstad, however. He also saw the mother tongue as crucial for the child’s social development and their sense of having a place in the world. The destructive revolution in the self that the loss of Sámi language would produce would also “tear the Sámi people by the root from the land it belongs in” in his eyes (P. Fokstad 1923, p. 122).

The crucial role that Sámi language had for maintaining a sense of being in space indicates the role of land in Fokstad´s philosophy. The child who lacks the words to speak to the land naturally also lacks the possibility of engaging in responsible relationships with land. This theme is perhaps better illustrated by reference to his curriculum, which I will now turn to.

2.2. Fokstad’s Curriculum for Sámi Education

The curriculum that Fokstad sent to the school committee in 1924 was a proposal for education reform with comments on time allocation, subjects, contents, and expected learning outcomes. It also contains a description of “conditions for the curriculum”, which, taken together, amounts to a systemic school reform. The proposal was published as part of the Parliamentary School Commission’s report in 1926 (Den parlamentariske skolekommisjon 1926). In the following, I will take a closer look at Fokstad’s curriculum by condensing and isolating its components. Table 2 outlines the content reform that Fokstad proposed for Sámi education, focusing on learning outcomes.

Table 2.

Condensed representation of the curriculum for Sámi comprehensive education as outlined by Fokstad, adapted from the Parliamentary School Commission’s report (1926).

A key facet of the curriculum is that it primarily relies on sense-based learning processes that aim to develop practical skills, and only secondarily focuses on theoretical knowledge formation. Fokstad emphasized that “first and foremost the school must accommodate the nature of children, in other words: the school for the child” (Den parlamentariske skolekommisjon 1926, p. 107). In his commentary on the subjects, he emphasized that the child’s life world had to be the point of departure in all learning processes, and that the fact that the child’s world was culturally Sámi would make a big difference. The learning outcomes are phrased through verbs that indicate “knowing how” at the expense of theoretical object knowledge (knowing that) (Hoveid and Hoveid 2019). He was concerned that Sámi children learnt practical skills that would help them contribute to the continuation of core Sámi livelihoods, such as reindeer husbandry. Among these skills were, of course, naming land and speaking about the interaction with land. Solveig Joks and colleagues have addressed how the relational approach to land is practice-based in Sámi language, expressed in verbs rather than nouns (Joks et al. 2020). The child who could only speak of land as object, noun, can in this sense be seen to have lost its grip on the very relation to land. This was disastrous in Fokstad’s mind, because the relationship with land was also a source for the collective strength that he called the national.

The subject that I have translated to Learning with the land (Hjemstedslære) highlights the importance of sense-based learning with the local environment. While also a similar subject in Norwegian curriculum at the time, Fokstad imagined it to have a different purpose in Sámi education. Learning with the land should develop care and skill in relation to the natural environment, but also awaken Sámi children’s “love for their people and their language” (Den parlamentariske skolekommisjon 1926, p. 106). Fokstad understood knowledge of and engagement with the natural environment as a particularly deep and advanced facet of Sámi culture, and therefore as a potential source of cultural love and pride. He also saw potential in this subject to work against the devaluation of reindeer husbandry as a way of life. By valuing traditional skills and knowledge, he hoped to validate children from reindeer herding families in particular, and Sámi culture in general.

Learning with the land was seen as the sensory-based practical foundation for the theoretical subjects including geography, history, and natural knowledge (today named natural science). In his commentary on the subject of natural knowledge, he complains that instruction in Norwegian had made Sámi children “helpless” in the description of their own environment, lacking both Sámi and Norwegian names for their surroundings (Den parlamentariske skolekommisjon 1926, p. 106). He expresses his concern that the loss of language was connected to the loss of a spiritually meaningful and practically necessary connection with the land. For Fokstad, this was not merely an epistemological loss of knowledge, but a loss in the very anchoring of the human being that would essentially endanger their mental health.

Fokstad understood that foundational changes in the organization of education were necessary if the school was to build a capacity to work with the curriculum he proposed. The existing school lacked practically all the resources needed: language proficiency, cultural knowledge, knowledge of the land, materials for instruction, and insight into the children’s living conditions. The few teachers that did have some of these capacities, like Fokstad himself, were kept on a tight leash by the state’s representative, the school director, and a teacher community of primarily Norwegian teachers who were skeptical of changes that exposed their own shortcomings in providing a useful education for Sámi children (Hoëm 1976). Fokstad’s conditions for the success of Sámi education as he envisioned it required a complete reorganization of the political power over education that amounted to Sámi self-determination in education. His conditions are listed in an abbreviated version in Table 3.

Table 3.

Fokstad’s conditions for the success of Sámi education. Adapted from the Parliamentary School Commission’s report (1926).

The conditions for the curriculum demonstrates Fokstad’s acute awareness that systemic change and collective effort in Sámi communities was necessary for the realization of Sámi education. He lamented the lack of both these components in his writing, perhaps because he was sorely aware of the limits of a single teacher’s agency. As a teacher in the Norwegian school system, Fokstad was not able to practice the pedagogy he envisioned in his writing (Ravna 2007), nor was he able to raise his own children to become fluent Sámi speakers (U. Fokstad 2017). Only towards the end of his life, in the 1960s and 70s, would he see a mobilization for education in the Sámi community that could realize the change he envisioned in the 1920s that could produce Sámi education institutions and create better social conditions for Sámi childrearing.

Fokstad’s curriculum from 1924 was immediately understood as a plan for indigenizing education. The school director in Finnmark at the time sardonically questioned if Fokstad intended to “lapponify education for all children in Finnmark—or perhaps even in our entire country?” (Zakariassen 2012, p. 284). Sámification of education for Sámi children was indeed Fokstad’s intention. Indigenization points to the transformative inclusion of indigenous knowledge and practices (Gaudry and Lorenz 2018). Fokstad’s plans for Sámification would necessarily be transformative because the change to Sámi as a language of instruction would alter the content, organization, and power relations in education considerably. Concerning content, the change of language would require that Sámi teachers and communities collectively found ways to express and convey the skills and knowledge needed for the educational processes to be realized. They hardly had Sámi language books to rely on, so the language shift was premised on a change from objectified knowledge in textbooks to relationally and communally produced skills and knowledge. Fokstad also lamented this fact and was eager to underline that the writing of textbooks in Sámi language had to be a high priority to rectify this situation (Den parlamentariske skolekommisjon 1926). Nevertheless, his proposal for the organization of education and Sámi self-determination in school matters suggests that he intended for the transformation of knowledge in education to take place. By insisting on local schoolhouses and local democratic control over schools, he opposed the educational universalism of the Norwegian state, and also insisted on the value of the Sámi communities’ skills and knowledge. If realized, the plan would amount to Sámi self-determination in majority Sámi districts.

In short, Fokstad’s plan aspired to demote the Norwegian teaching class from its position as the experts of what knowledge was worth learning. This is probably the main reason why his plan was both praised for its merit and rejected completely in practice. In a meticulous empirical analysis of the Norwegian education system in the Sámi core districts in the first half of the 20th century, Anton Hoëm found that a majority of the students received no formal education, as they fell short of the minimum standards of the national curriculum. In addition, they learnt no practical skills that could help them develop their livelihoods in the local communities (Hoëm 1976). The schools failed to reach the goals of education it professed to have. Hoëm demonstrated how the Norwegianization policy in schools in Finnmark was upheld by a power alliance between the state and influential Norwegian teachers that effectively barred all critical feedback on the pedagogical practice from coming into consideration (Hoëm 1976, p. 340).

These power relations are crucial for understanding how the seemingly progressive Norwegian curriculum for the country school from 1922, and the even more democratically minded curriculum from 1936, could amount to the system of oppression that education was in the Sámi core areas in Fokstad´s time. The power structure was also central in producing the profound sense of disillusionment with the Norwegian democratic system that Fokstad personally struggled with throughout his lifetime. Although Fokstad met wide acclaim among his academic colleagues for his work on the school plans from 1924, no significant change followed. Twenty-five years later, he was invited again by Norwegian authorities to give his opinion on school reform through membership in the committee for coordination of education. Fokstad’s advice for school reform was essentially the same (Samordningsnemda for skoleverket 1948).

3. Discussion

Thinking with Martin Nakata’s concept of “cultural interface” between indigenous and western systems of knowledge is useful when considering Fokstad’s contribution to the philosophy of education (Nakata 2007; Olsen and Sollid 2022). In Fokstad’s intellectual context, the centrality of feelings in learning processes and the notion of a collective articulation of a cultural project were ideas that circulated widely. At that time, his contribution was showing how education could help people who were classified as “natural” rather than “cultural” to aspire to a flourishing future based on its own knowledge system. The mother tongue was the key that unlocked the possibility for equal rights to education in his thinking.

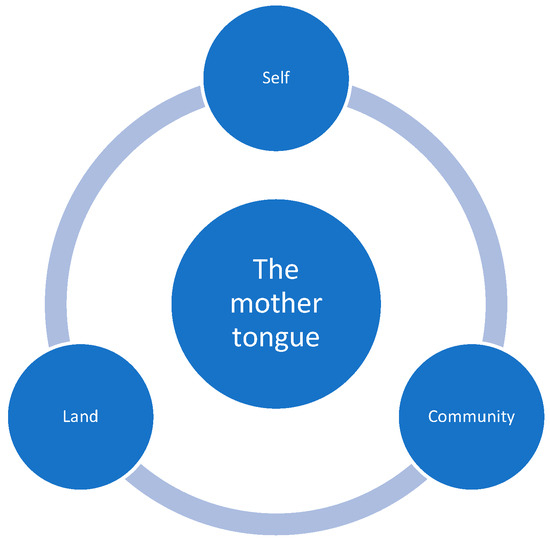

In our contemporary cultural interface, Fokstad´s philosophy of education can serve as an articulation of the key principles of the indigenization of education, where language can serve as a point of departure. Figure 1 below is an illustration of how Fokstad imagined how education could become educational for the Sámi people. The illustration shows how his foundational ideas about teaching and learning remain a key contribution to thinking about what the purpose of education is.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the mother tongue in Fokstad’s educational philosophy.

The key elements in this figure are similar to the drum model of Sámi education that Pigga Keskitalo and colleagues developed. Like Fokstad, they center the language in their articulation of the Sámi educational project, and explain how the language can in turn connect to both community and land (Keskitalo et al. 2013, p. 91). Their model does not point inward to the child’s sense of self, however. In the current cultural interface, Fokstad’s insistence on the relationship between language, land, community, and the child´s sense of self can still be a contribution to philosophies of Sámi education. The educational psychology in Fokstad´s thinking reminds the reader that the language of the heart, the mother tongue, and the mental health of the child need to be developed in tandem for children to grow a healthy psyche.

In my modelling of Fokstad’s philosophy, the mother tongue is both the medium and the product of the relationship between self, community, and land. As such, it can be seen as a holistic vitalism that highlights land and collectivity as sources of human strength of spirit. This reading is informed by Fokstad’s insistence that his concept of “nation” was qualitatively different from that in the European tradition (P. Fokstad 1967, pp. 48–49). Kortokangas shows how Fokstad expresses his ideas about the national spirit in his texts for a Sámi audience (Kortekangas 2021, p. 98). Kortekangas envisioned a “’rehabilitation’ of Sámi enlightenment through Sámi-language literature, music, and other aspects of culture” (Kortekangas 2021, p. 98).

Fokstad would not abandon his concept of nation (P. Fokstad 1967). Even after World War II, when he understood that the term “nation” would easily be misunderstood, he insisted on developing the concept. He worked it into a concept of the collectivity of the human spirit that also enlisted the relationship with body and land. Far from the “essentialism” it has been reduced to (Zakariassen 2012, p. 288), Fokstad’s philosophy was based on a vitalism that acknowledged collectivity and engagement with land as components of human strength of spirit.

School director Brygfjeld’s insinuation that Fokstad would not stop with Sámifying education for Sámi children suggests that he both understood, and disapproved of, the implications that Fokstad’s curriculum had for the Norwegian education system. The consequence would necessarily be that linguistic and cultural plurality would become a key facet of the Norwegian education system (Eriksen and Niemi 1981), and hence that rudimentary knowledge of Sámi languages at the minimum should be expected of non-Sámi teachers and officials that dealt with Sámi education. The contribution Fokstad made to the realization of the equal right to education can also serve as an additional explanation for why his plans were not supported by the Norwegian government. School director Brygfjeld insinuated that Fokstad’s plan would inspire the demand for a similar education for Kvæn children in the language-blended districts (Zakariassen 2012, p. 286). The parliamentary school committee was keen to underline that they did not think that this was a logical extension of any accommodations of Sámi language. Fokstad’s philosophy of education suggests that the relationship between self, community, and land expressed in the mother tongue is the foundation for the spiritual growth for all children. If we consider this in the light of Norwegian education history, the Norwegian state has made several admissions of Sámi rights to education in the mother tongue, without changing the principle of monolingual and monocultural education as the baseline of Norwegian education in relation to all other linguistic minorities (Pihl 2010). The basic fault that Fokstad identified is a core facet of Norwegian basic education today, and continues to produce injustice in education.

4. Conclusions

It has been widely commented that Fokstad was ahead of his time. In his work, he expressed a profound sense of intellectual isolation and an existential loneliness (T. E. Dahl 1970; U. Fokstad 2017). Perhaps this was partly due to his Bergsonian temporal dualism—he could see time both as the mechanic passing of time, and as lived duration. Splitting time in this way potentially also splits open the evolutionism that claimed that Sámi and other indigenous people were destined to pass into history, widely circulated in Fokstad’s time. He could envision another future for education and for the Sámi people. His educational philosophy can help us envision another future for education again today. To salvage this legacy, it is necessary to keep asking what the purpose of education in general, and indigenous education in particular, should be. For Fokstad, the purpose of education was to nourish the spontaneous expression of the child through which they could connect their inner emotional world with their surroundings. The language of spontaneous expression is the mother tongue. The mother tongue is also the language of love that is needed to welcome the child´s spontaneous expression into the world. Fokstad imagined that children who were educated with love in the mother tongue would grow the capacity to express love and care for the self, significant others, and their natural surroundings. Today, practically all Sámi children who speak a Sámi language are bilingual. While this seemingly complicates the role of the mother tongue in Sámi education, Fokstad’s key ideas still give guidance. The mother tongue is the child’s language of spontaneous expression, and while it is the origin of the connection between self, community, and land, it is also the product of these interactions and therefore continually changing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data publicly available. See Table 1.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Andresen, Astri, Bjørg Evjen, and Teemu Ryymin. 2021. Samenes Historie fra 1751 til 2010. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell Pearson, Keith. 2018. Bergson: Thinking Beyond the Human Condition, 1st ed. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Balto, Asta. 2005. Traditional Sámi Child Rearing in Transition: Shaping a New Pedagogical Platform. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 1: 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Helge. 1957. Språkpolitikk og Skolestell i Finnmark 1814–1905. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, Tor Edvin. 1970. Samene i Dag-og i Morgen. En Rapport. Oslo: Gyldendal. [Google Scholar]

- Den parlamentariske skolekommisjon. 1926. Del II Utkast til lov om Folkeskolen på Landet. Edited by Den parlamentariske skolekommisjon. Oslo: Det Mallingske Boktrykkeri. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, Knut Einar, and Einar Niemi. 1981. Den Finske Fare. Sikkerhetsproblemer og Minoritetspolitikk i Nord 1860–1940. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Fokstad, Per. 1917. Hvordan fornorskningen i barneskolen grep ind i mitt liv. In Fornorskningen i Finnmarken. Edited by Johannes Hidle and Jens Otterbech. Kristiania: Lutherstiftelsens Boghandel, pp. 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fokstad, Per. 1923. Samiske tankar og krav. Norsk Aarbok 4: 120–30. [Google Scholar]

- Fokstad, Per. 1926. Tilleggsmateriale til Boka Samisk skolehistorie 5. Available online: http://skuvla.info/skolehist/parlskol-tn.htm (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Fokstad, Per. 1950. En side ved det samiske problemet (An aspect of the Sámi problem). Samtiden 59: 301–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fokstad, Per. 1957. Litt om samisk kunst. (Notes about Sámi art). In Sámiid dilit. Föredrag ved den nordiska samekonferensen Jokkmokk 1953. Madison: Merkur Boktrykkeri, pp. 102–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fokstad, Per. 1967. Litt om det samiske problemet sett innenfra. Sámi ællin: Sámi særvi Jakkigir’ji. Sameliv: Samisk Selskaps årbok 6: 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fokstad, Per, and Jens Otterbech, eds. 1920. Kulturværdier hos Norges finner. Oslo: H. Aschehoug. [Google Scholar]

- Fokstad, Unni Schøn. 2017. Visjonæren og Nasjonsbyggeren. Per Fokstads Kamp for Samisk Språk og Kultur. Kárášjohka: ČálliidLágádus. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 2013. Truth and Method. Bloomsbury Revelations. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudry, Adam, and Danielle Lorenz. 2018. Indigenization as inclusion, reconciliation, and decolonization: Navigating the different visions for indigenizing the Canadian Academy. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 14: 218–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjessing, Gutorm. 1973. Norge i Sameland. Oslo: Gyldendal. [Google Scholar]

- Hætta, Odd Mathis. 1999. Per Fokstad. Portrett av en visjonær samisk pioner. In -Dasgo Eallin Gáibida Min Soahtaái ja Mii Boahtit-Miiboahtit Dállán!-Selve Livet Kaller oss til Kamp og vi Kommer-vi Kommer Straks! Edited by John T. Solbakk and Aage Solbakk. Kárášjohka: ČálliidLágádus, pp. 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hoëm, Anton. 1976. Makt og Kunnskap. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Hoveid, Halvor, and Marit Honerød Hoveid. 2019. Making Education Educational. Contemporary Philosophies and Theories in Education. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- James, William. 1899. Talks to Teachers on Psychology; and to Students on Some of Life’s Ideas. New York: Henry Holt & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Eivind Bråstad. 2015. Tromsøseminarister i Møte med en Flerkulturell Landsdel. Stonglandseidet: Nordkalottforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Joks, Solveig, Liv Østmo, and John Law. 2020. Verbing meahcci: Living Sámi lands. The Sociological Review (Keele) 68: 305–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, Åsa Nordin. 2011. Ethical guidelines for the documentation of árbediehtu, Sami traditional knowledge. In Working with Traditional Knowledge: Communities, Institutions, Information Systems, Law and Ethics. Edited by Jelena Porsanger and Gunvor Guttorm. Guovdageaidnu: Sámi Allaskuvla, pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kemi Gjerpe, Kajsa. 2017. Samisk læreplanverk–en symbolsk forpliktelse? Nordic Studies in Education 37: 150–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskitalo, Pigga. 2022. Timelines and strategies in Sami education. In Indigenising Education and Citizenship. Perspectives on Policies and Practices From Sápmi and Beyond. Edited by Torjer Olsen and Hilde Sollid. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Keskitalo, Pigga, Kaarina Määttä, and Satu Uusiauttu. 2013. Sami Education. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Kortekangas, Otso. 2021. Language, Citizenship, and Sámi Education in the Nordic North, 1900–1940. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, Svein. 2003. Samisk Skole Eller Norsk Standard? Reformene i Det Norske Skoleverket og Samisk Opplæring. Kárášjohka: Davvi Girji. [Google Scholar]

- Magga, Ole-Henrik. 2005. Indigenous Education. Childhood Education 81: 319–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minde, Henry. 2005. Fornorskinga av samene. Hvordan, Hvorfor og med hvilke følger? Gáldu Čála-Tidsskrift for Urfolks Rettigheter 3/2005: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nakata, Martin. 2007. The Cultural Interface. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 36: 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyyssönen, Jukka. 2018. Narratives of Sámi School History in Finland: The Histories of Assimilation Made Visible. Nordic Journal of Educational History 5: 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Olsen, Torjer A., and Hilde Sollid. 2022. Introducing Indigenising education and citizenship. In Indigenising Education and Citizenship. Edited by Torjer A. Olsen and Hilde Sollid. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Otterbech, Jens, and Johannes Hidle, eds. 1917. Fornorskningen i Finmarken. Kristiania: Lutherstiftelsens Boghandel. [Google Scholar]

- Pihl, Joron. 2010. Etnisk Mangfold i Skolen. Det Sakkyndige Blikket. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Porsanger, Jelena. 2011. The Problematisation of the Dichotomy of Modernity and Tradition in Indigenous and Sami contexts. In Working with Traditional Knowledge: Communities, Institutions, Information Systems, Law and Ethics. Edited by Jelena Porsanger and Gunvor Guttorm. Guovdageaidnu: Sámi Allaskuvla, pp. 225–52. [Google Scholar]

- Porsanger, Jelena, and Gunvor Guttorm. 2011. Working with Traditional Knowledge: Communities, Institutions, Information Systems, Law and Ethics. Dieđut. Guovdageaidnu: Sámi Allaskuvla, vol. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Porsanger, Jelena, and Irja Seurujärvi-Kari. 2021. Sámi dutkama máttut: The Forerunners of Sámi Methodological Thinking. In Indigenous Research Methodologies in Sámi and Global Contexts. Edited by Pirjo Kristiina Virtanen, Pigga Keskitalo and Torjer Olsen. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 33–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ravna, Ragnhild. 2007. Minner fra skolen i Tana–Med spesiell vekt på samarbeidet med Per Fokstad. In Samisk Skolehistorie 2. Edited by Svein Lund, Elfrid Boine and Siri Broch Johansen. Karasjok: Davvi Girji. [Google Scholar]

- Samordningsnemda for skoleverket. 1948. Del III Tilråding om Samiske skole-og Opplysningsspørsmål. Edited by Kirke-og Undervisningsdepartementet. Oslo: Kirke-og Undervisningsdepartementet. [Google Scholar]

- Sannhets- og forsoningskommisjonen. 2023. Sannhet og Forsoning—Grunnlag for et Oppgjør Med Fornorskingspolitikk og Urett Mot Samer, Kvener Norskfinner og Skogfinner. Edited by Stortinget. Oslo: Stortinget.no. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, Mark. 2020. Bergson. Edited by Brian Leiter. The Routledge Philosophers. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen, Stine H. Bang. 2021. Saami Women at the Threshold of Disappearance: Elsa Laula Renberg (1877–1931) and Karin Stenberg’s (1884–1969) Challenges to Nordic Feminism. In Feminisms in the Nordic Region. Edited by Suvi Keskinen, Pauline Stoltz and Diana Mulinari. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 155–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zakariassen, Ketil. 2012. Samiske Nasjonale Strateger. Isak Saba, Anders Larsen og Per Fokstad 1900–1940. Karasjok: ČálliidLágádus. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).