Abstract

About half of Luanda’s population comprised enslaved people in the mid-nineteenth century. Although scholars have examined the expansion of slavery in Angola after the end of the transatlantic slave trade and the use of slavery to underpin the trade in tropical commodities, the labor performed by enslaved children has been neglected. This study explores the experiences of enslaved children working in Luanda during the era of the so-called “legitimate” commerce in tropical commodities, particularly between 1850 and 1869. It draws upon slave registers, official reports, and the local gazette, the Boletim Oficial de Angola, to analyze the means through which children were enslaved, the tasks they performed, their background, family connections, and daily experiences under enslavement. This paper argues that masters expected enslaved children to perform the same work attributed to enslaved men and women. After all, they saw captives as a productive unit irrespective of their age.

1. Introduction

In 1855, the nine-year-old enslaved girl Felippa walked down the streets of Luanda, the capital of the Portuguese colony of Angola, with a basket on her head selling foodstuffs provided by her mistress, a Black woman named Joanna Francisco.1 Joanna owned a total of eight captives, five of whom were children between the ages of five and nine years old. Two of them had their occupation identified: the nine-year-old fisherman António Francisco and the aforementioned quitandeira or itinerant vendor Felippa.2 In the 1850s, about half of Luanda’s population was composed of enslaved laborers who worked in workshops and the streets, as well as in domestic services in the households of residents and cultivating the land in the agricultural suburbs.

Historians have analyzed the volume, origin, and gender profile of Luanda’s enslaved population in the mid-nineteenth century. Mario António Fernandes de Oliveira was the first to look at the enslaved population of Luanda after the era of the slave trade, noting that the inhabitants of the city, as well as the owners of farms and plantations established in the interior, depended on the labor of enslaved Africans (). José C. Curto analyzed the “demographic explosion” seen in Luanda after the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in 1836. His study shows that the city absorbed a growing number of enslaved laborers to perform the work required in the trade of tropical commodities and to meet the needs of the urban population (). Vanessa S. Oliveira analyzed the gender profile of the enslaved population, demonstrating that during the era of the trade in tropical commodities, enslaved men found opportunities in artisan crafts. At the same time, women were limited to performing domestic services and retail sales (). Despite the contribution of these scholars to expand our knowledge of the volume, gender, and occupational profile of the enslaved population, no research has been published on the enslaved children living in this urban landscape previously known as the single most important Atlantic slaving port.

This study sheds light on the experiences of enslaved children working in Luanda during the era of the so-called “legitimate” commerce in tropical commodities, particularly between 1850 and 1869.3 It draws upon slave registers, official reports, and the local gazette, the Boletim Oficial de Angola, to reconstruct the trajectories of enslaved boys and girls. This contribution attempts to answer the following questions: What were the means through which children became slaves? What types of tasks did the enslaved children perform? What do primary sources reveal about their background, families, and daily experiences under enslavement? This paper argues that masters expected enslaved boys and girls to perform the same tasks attributed to enslaved men and women. After all, masters saw captives as a productive unit irrespective of their age.

2. Luanda, a Slave Society

During the transatlantic slave trade, Luanda occupied the position of the single most important Atlantic slaving port. 2.8 million Africans departed from this port between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, with about 535,000 shipped during the nineteenth century alone (). In 1836, Portugal abolished the slave trade from its possessions in Africa, initiating the prosecution of illegal slave cargoes and the destruction of barracoons along the coast. Although the slave trade from Luanda had ceased by 1840, merchants previously operating in the city shipped captives illegally until the late 1860s from alternative locations, including the northern African-controlled ports of Cabinda, Ambriz, and Loango, to supply particularly the Brazilian and Cuban markets.4 Table 1 describes the destinations and numbers of Captives Shipped from Luanda during 1801–1850.

Table 1.

Destinations and Numbers of Captives Shipped from Luanda, 1801–1850.

Portuguese authorities in Lisbon and Luanda hoped that the trade in tropical commodities such as ivory, wax, coffee, sugar, and cotton would replace slave trading. However, the two trades proved to be complementary rather than exclusive. Luanda slave traders invested in the trade in tropical commodities while they continued to ship captives illegally (). Slave traders based in Luanda established plantations and warehouses in the hinterland from where they traded tropical commodities and smuggled captives. For example, José Maria Matoso da Câmara invested in commercial agriculture while continuing to ship captives to Brazilian ports with his associate Augusto Garrido. In 1846, one of their vessels was captured after disembarking captives in Cabo Frio, in the state of Rio de Janeiro.5

The final blow to the slave trade came in 1850 when Brazil prohibited the importation of captives. After that, foreign slave traders of Portuguese and Brazilian origins based in Luanda relocated to Portugal, Brazil, and New York (). Luso-African slave dealers, on the other hand, placed their captives on plantations in the Luanda hinterland, where they cultivated coffee and cotton to supply European and North American markets. For example, the Luso-African Dona Ana Joaquina dos Santos Silva was among the wealthiest slave traders in Luanda. She invested in the production of sugar and aguardente (sugarcane brandy) while she continued to ship captives illegally to Brazil. By the 1850s, her numerous captives were working in Luanda as well as on agricultural properties and warehouses she owned in the interior (; ; ; ). When, in the early 1850s, the then secretary of the Luso-British Mixed Commission Francisco Travassos Valdez visited one of Dona Ana Joaquina’s sugar mills in the District of Bengo, the overseer informed him that she had some 1400 captives on that property alone working in various occupations ().

From the early 1800s to 1844, Luanda’s population experienced a constant decline due to the intense demand for captives in the Atlantic market (). Following the ban on the slave trade, however, the number of Luanda’s residents began to rise again: in 1844, the number of inhabitants in the colonial capital reached 5605, while in 1850, there were 12,565 individuals composed of 1240 brancos (whites), 2055 pardos (of mixed European and African descent) and 9270 pretos (Blacks). Almost half of the population (6020) was enslaved, suggesting that the demographic growth resulted from the retention of captives who would otherwise have been exported to the Americas. As in other Atlantic ports, Luanda’s population was female-dominated, with free and enslaved women together accounting for about 57 percent of inhabitants (). The number of enslaved people reduced gradually in the second half of the nineteenth century, with many moving into the category of libertos (freed) through manumission, ransom, or rescue from illegal slave cargos. In 1869, Portugal freed all remaining captives in their overseas territories in Africa. However, they had to continue serving their former masters until 1878, when they finally achieved full emancipation ().

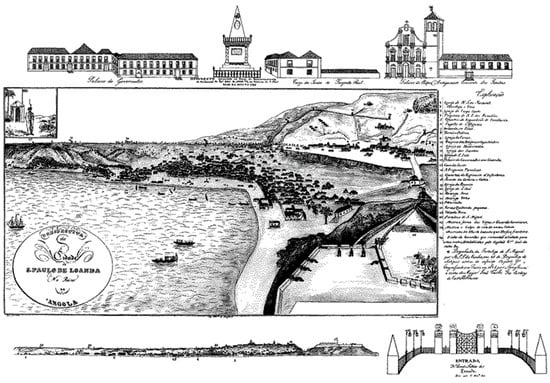

Nineteenth-century Luanda (see Figure 1) was predominantly an African city: most inhabitants were West Central Africans who spoke Kimbundu and practiced Mbundu rituals. Even Africans who had converted to Christianity did not wholly abandon their religious practices, continuing to engage in indigenous religious rituals (; ). Some white residents adopted elements of Mbundu culture, including the Kimbundu language and participating in indigenous rituals and practices.6

Figure 1.

View of Luanda’s Upper and Lower Towns, 1825. Source: “Prespectiva da Cidade de S. Paulo de Loanda no Reino de Angola”, 1825, Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, Iconografia Impressa.

Elite men and women-owned captives for their labor and as a symbol of prestige (). According to Portuguese Joaquim José Lopes de Lima, the wealthiest families held numerous captives, who “crowded the houses as luxury objects.” He noted that “it is common to find ten, twelve, or twenty slaves at a bachelor’s house who would find it difficult to employ two or three servants” (). The enslaved were the main labor force in the workshops, streets, and markets, as well as in the households of the elite and on their plantations and arimos (agricultural properties) located in the interior. The wealthy also displayed their captives on walks through the city and in public functions, when they were carried in hammocks and followed by an entourage of enslaved men and women. The French Jean Baptiste Douville visited Luanda in the late 1820s, noting that “when the wealthiest ladies show themselves outside of their households.… they are then followed by a multitude of slaves that, the first time I saw one of those trains I confused it with a procession” (). These public appearances enhanced the prestige of elite men and women in local society.

3. Producing Enslaved Children

In West Central Africa, children were enslaved by various means. Some were born into slavery because their mothers were enslaved themselves. In Portuguese Angola, the child’s status followed that of the mother, whether the father was enslaved or free. Therefore, the children of an enslaved woman were not legally her offspring but the property of her master (). Baptism records provide genealogical information of enslaved children brought to the baptismal font by their parents. Enslaved women bore children from enslaved men through casual encounters and long-term relationships. Efigênia, a slave of Dona Josefa Fonseca, gave birth to her son Joaquim on 25 July 1815. The infant was baptized in the Church of Our Lady of Remédios on 13 August as the natural son (born from unmarried parents) of Efigênia and António José, a slave of Judas Theodoro.7 Some enslaved couples baptized more than one child, which suggests that they were in a long-term relationship. This was the case of Joaquim Bartolomeu and Domingas José, slaves of Captain Januário António de Souza Gomes. The couple brought two infants to the baptismal font: José received the sacrament in May 1816, while his sister Josefa was baptized in April 1820.8 Captives who belonged to the same masters and lived in the same household were likelier to establish long-term relationships and families. These enslaved men and women were not married according to the rites of the Catholic Church; nevertheless, they chose to baptize their children, evidencing that they recognized affiliation to Christianity as an important element for the social insertion of their offspring into local society. In addition, Christian baptism helped establish or reinforce networks with godparents that could protect and, in some cases, even manumit enslaved children ().

Enslaved women also bore children to free men. On 15 April 1815, Catharina Manoel gave birth to a daughter, Maria, fathered by her master, João Esteves da Costa. Maria was baptized the following month as the natural daughter of Catharina and Costa.9 Some masters freed their children born from enslaved women during baptism, but the practice was not mandatory. Despite acknowledging the paternity of Maria, Costa did not free his daughter or her mother, who was then condemned to life under slavery. Although some women were able to achieve benefits by becoming the sexual partners of free men, including manumission for themselves and their children and access to material goods, this was not the norm (; ). Some free men listed as fathers in the baptism records did free their children born from enslaved women during baptism. The infant João, for example, was brought to the baptismal font on 27 January 1817 by his parents, the free man Luís Gonçalo and Josefa António, slave of Lieutenant Francisco Dias Machado. In the baptismal register, Gonçalo declared to have purchased his son’s freedom.10 Other free men only acknowledged the paternity of enslaved children on their wills when they made provisions to manumit their offspring and, sometimes, the enslaved mothers. Some neglected their children of enslaved status completely, most likely because they were the result of adulterous relationships or due to racist beliefs. Whether the children born from enslaved women and free men resulted from rape or “consensual” sex is difficult to ascertain, as enslaved women everywhere had virtually no choice in sexual matters (; ).

Young children were subjected to the violence and mistreatment inherent to slavery, including physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. Even young girls were abused by unscrupulous masters who saw sex as an extension of the services female captives were supposed to provide. In March 1846, Filipe Bernardino, a Black man, was accused of raping a six-year-old enslaved girl in the immediate hinterland of Luanda. The act seemed to have shocked the community and local authorities as the perpetrator was rapidly apprehended and sentenced to corporal punishment followed by imprisonment.11 In this case, the victim’s age was crucial for the charges imposed on the perpetrator. Had the victim been an adult woman, Bernardino’s actions would have been normalized.

Some enslaved children were not born into captivity. Instead, they were captured in warfare and attacks against villages organized by bandit groups. In these cases, genealogical information is missing. Warfare generated many captives who could be sold internally or to smugglers. Women, elders, and young children were particularly easier prey because they were less likely to escape the attacks. The mobility of women was compromised by the need to protect children, while elders were less agile. Some of the very young and very old perished during the long march from the place of capture to the coast. Among those who survived, women were more likely to be sold into the domestic market since African societies generally preferred enslaved women to men because of their productive and reproductive capacities. Women played a major role in the production of foodstuffs in agricultural societies and contributed to increasing kinship groups (). Meanwhile, Atlantic slave traders wanted male captives as Europeans believed that men worked harder than women and had knowledge of tropical agriculture (; ).12 The young children were also likely to remain in Africa because, despite their usefulness for avoiding taxes and the fact that they could be more densely packed onto ships, they were widely regarded as unlikely to survive the middle passage (). In addition, children required longer investments until they became adults. This pattern, however, changed in the nineteenth century when slave cargoes started shipping more children, particularly from West Central and Southeast Africa ().

Kidnapping and the punishment of ordinary crimes (debit, witchcraft, adultery, and theft) through enslavement became common to meet increased demands for enslaved laborers in the external market, particularly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The domestic market also absorbed some of these captives. Children were kidnapped despite the illegality of the practice for both the Portuguese and indigenous communities (). Even people born into areas under Portuguese control and converted to Christianity who were supposed to be protected against enslavement became victims of bandit groups. José C. Curto and Mariana P. Candido have explored cases of women and young children kidnapped in the Angolan interior (; ). Their work shows that families who had connections with indigenous and Portuguese authorities were able to fight the unlawful enslavement of their relatives. Many other victims of kidnapping, however, lacked those connections and the means to pay a ransom.

Children were often used as pawns, a practice in which a person was held as collateral for a debt. As practiced in several communities in Western Africa, pawnship prevented the arbitrary seizure of goods or people in paying for debts, as the pawn guaranteed the debt would be repaid (). Pawns were not slaves, although they could be enslaved in the absence of mechanisms that protected pawned persons. Some children pawned by their relatives could end up being sold as captives in the absence of payment ().

During drought and crop failure periods, some families might have resorted to selling children. This practice could secure access to food and protection from powerful individuals helping other family members (). Between 1801 and 1830, the population of Luanda and its immediate hinterland experienced at least three major droughts that resulted in food shortages (). On these occasions, vessels from São Tomé and Brazil transported beans and manioc flour to the Luanda public market, the Terreiro Público, to alleviate the hunger of the urban population ().

4. Searching for Enslaved Children

Angola holds one of the wealthiest collections of historical documentation in sub-Saharan Africa (; ; ). As a slave society, the enslaved appear everywhere in the documentation generated in the colony until the abolition of slavery in 1869: they show up in wills and inventories, parish records; in the Boletim Oficial de Angola, the local gazette published from 1845 onwards; and in travel accounts—just to mention a few available sources. In addition, in the second half of the nineteenth century, the Portuguese administration produced another set of documentation containing data on the enslaved population of the colony: the registros de escravos, or slave registers. On 10 December 1854, a decree from Sá de Bandeira, then President of the Conselho Ultramarino (Overseas Council) in Lisbon, demanded the registration of captives in Portugal’s overseas possessions (). Through compulsory registration, the administration could get a sense of the labor resources available in the areas under Portuguese control to promote the economic development of Angola and establish control over the tax payment on enslaved laborers’ ownership. The decree generated a series of registers in Luanda and the interior districts, known as presídios, currently held in the National Archive of Angola, Luanda. The database slaveregister.org houses the registers of 12,000 captives working in Luanda and its hinterland between 1850 and 1869, containing information such as name, sex, place of origin, age, body marks, and occupation of captives, as well as the names and the places of residence of slave owners.13

We do not know whether captives or their masters provided the information on the registers nor how much input colonial officials had. In any case, these data indicate the range of uses of slave labor in Luanda and the immediate interior after 1850, when the illegal shipment of captives entered its decline phase, and the city’s economy shifted towards the trade in tropical commodities. This documentation lists a high number of children among the enslaved population of Luanda and its hinterland, from infants registered with their mothers to individual boys and girls. By combining the slave registers, travel accounts, parish records, and the Boletim Oficial de Angola, we can get a better understanding of the daily experiences of enslaved children in Luanda.

In the official documentation, the Portuguese divided children by crias de peito, meaning the infants still being breastfed, and the crias de pé, or children who could walk and measured up to quatro palmos or three feet (91 cm). Crias de peito were usually registered with their mothers and were exempted from tax payments. This was the case of a cria de peito registered with her mother Jacintha, slave of António Lopes da Silva, in 1863.14 Sometimes, infants were registered on their own, indicating that their mothers might have died. The slave owner Maria João da Silva Guimarães registered an unnamed seven-month-old infant in 1855.15 Likewise in 1863, Candido José dos Santos Guerra registered the three-month-old infant Maria.16 Both registers did not indicate the names of the mothers, which suggests that they might have died. Sometimes masters registered deceased captive women, noting that they were survived by their crias de peito. Cabongo, an enslaved woman who belonged to the owners of the farm Colônia de São João, died on 4 January 1861, leaving a three-month-old infant whose sex and name were not identified.17 Some enslaved women were registered with multiple children. This was the case of Lumba, slave of Dona Máxima Lemos Botelho de Vasconcelos, who in 1855 lived on her mistress’ arimo in Calumbo with her three children.18 It is possible that some slave owners incentivized their captive women to have children, which increased their human property ().

Some crias de pé were registered alone, separated from their mothers. Paula, Feliciana, and Domingos, slaves of Dona Ana Joaquina dos Santos Silva, were originally from Kongo.19 The three children were registered individually without reference to their mothers. They were likely separated from their mothers at capture or during their sale in Luanda. Children could also be separated from their mothers after the death of an owner, when assets, including captives, were divided among the heirs. Dona Ana Ubertaly de Miranda was a prominent slave trader and slave owner in Luanda, owning numerous captives, real estate, land, cattle, gold, iron bars, and sailing vessels, among other goods.20 She died in July 1848, leaving a will; some of her captives were divided among her heirs while others went to public auction, including the enslaved girl Domingas Mathias, whose age was estimated to be between ten- and twelve years old.21 A man named António dos Santos purchased Domingas on August 1848; the little girl, however, refused to follow her new owner “calling for her mother who watched the scene in tears”. Mother and daughter were separated in the division of the assets left by Dona Ana Ubertaly. In her will, Dona Ana had freed an enslaved woman and gifted her a captive who happened to be Domingas’ mother. She, however, made no provisions to avoid the separation of mother and daughter. The inspector of the Royal Treasury, Francisco Assis Pereira, moved by the scene, asked whether António dos Santos would be willing to free the little girl, to which he answered that his modest means did not allow him to do so. Pereira then made an irresistible offer, purchasing Domingas and automatically granting her freedom. A couple of days later, Pereira purchased Domingas’ mother and issued her manumission letter, reuniting mother and daughter. The story of Domingas and her mother made it to the pages of the local gazette, the Boletim Oficial de Angola, where Pereira was congratulated for his noble action.22

Captives were often sold when their masters faced economic difficulties, particularly enslaved children. Despite their young age, some enslaved children in the registers had several masters. In 1855, eleven-year-old Emília was registered as a slave of Amâncio José da Silveira. In July 1858, her master sold her to a man named Faustino José Cabral. A month later, Emília was sold again to Joaquim Eugênio Ferreira.23 This might indicate that Emília did not behave as expected or that her owners needed money and did not hesitate to sell enslaved children, sometimes separating them from their mothers.

Captives were branded with iron with their master’s initials, and young children were not exempted from this practice (). José Inácio Ferreira branded his captives with the mark JF. Not even two-year-old Zumba escaped the torture: the official who wrote her register in 1855 did not fail to notice that the little girl had been branded in her left chest.24 Similarly, a two-year-old unnamed boy registered in 1862 had the mark PE in his chest.25 Some masters branded their captives more than once. In 1855, twelve-year-old Miguel, a slave of José Inácio Ferreira, had the mark JF on his right and left chest.26 Eleven-year-old António had been marked with the initials BD in both arms and chests in 1855.27 It is hard to explain why a master branded the same captive more than once. It could be that the first attempt did not achieve the desired result due to resistance by the child or complications in the healing process.

5. The Labor of Enslaved Children

Many captives in Luanda performed skilled work and had their occupations listed in the slave registers. Masters enrolled enslaved men in workshops where they received training in artisan crafts to become cobblers, masons, tailors, carpenters, and barbers, among other skilled occupations. These specialized captives were more likely to find jobs in one of the many workshops, in public works undertaken by the colonial administration, or they could provide service to the urban population. Captives working independently had to pay a weekly or monthly fee to masters and could keep the remainder. Some were even able to purchase their manumission (). Enslaved women, however, were excluded from workshops, which limited their opportunities to domestic services and the retail trade of streets and markets (; , , ). In any case, enslaved women received training to perform domestic work as demonstrated by an announcement published in the local gazette, the Boletim Oficial de Angola in 1851: “Learn Italian, basic French, how to read and write, play the piano, dance, embroider, sew, and morals; we also teach enslaved women how to do laundry, sewing, starching and ironing; located in Quitanda Grande Square”.28

The work children performed was not different from that required of adult slaves. The enslaved boys whose occupations were listed in the registers were locksmiths, tailors, carpenters, fishermen, cobblers, cooks, porters, barbers, and masons. Most were listed as apprentices, which indicates that they were in the process of learning the trade. In 1855, the merchant Albino José Soares had thirteen boys aged between nine and twelve years old receiving training in workshops to become masons and carpenters.29 In 1867, two enslaved boys belonging to Dona Josefa de Mores were receiving training in workshops: twelve-year-old Augusto was a barber apprentice while Jacintho, of the same age, was learning carpentry.30

As was the case with enslaved women, enslaved girls were commonly listed as itinerant vendors, seamstresses, and washerwomen. In 1863, José Maria de Castro had two enslaved girls, six-year-old Mariana, and four-year-old Josefa, training to become seamstresses.31 António José de Souza e Silva registered two enslaved girls in 1867: seven-year-old Maria João was learning the art of sewing while ten-year-old Martha Miguel was receiving training to become a cook.32 Most girls attended to the needs of their masters’ families. However, they could also be rented out to anyone interested in their services ().

Itinerant traders seem to not have required specialized training as no girls were listed as apprentices of quitandeira. The absence of training meant that girls too young to perform other trades could be employed as itinerant vendors. Jacinta Manoel and Francisca, slaves of Augusto Teixeira de Figueiredo, were four and seven years old in 1867, respectively. Despite their young age, they were both listed as quitandeiras. The colonial officer in charge of the registration also took note of their thinness.33 It is likely that the two girls were provided a poor diet, which resulted in loss of weight.

6. Freedom, at Last

Some children were manumitted by masters or through the efforts of their mothers. Slave owners sometimes freed the offspring of their slaves during baptism, motivated by piety or in compensation for years of good service. For instance, the twins Madalena and Maria, baptized on 26 November 1815, natural daughters of Maurício Inácio and Catarina João, were then freed by their widowed mistress, Dona Ana Lopes, in gratitude for the good services the couple had provided.34 On 19 February 1817, Dona Joana Moreira António freed the enslaved boy António, son of her slave Maria António, in recognition of her years of good service.35 Brigadier António João de Menezes also granted manumission to Guilherme, son of his slaves Angélica Pedro and Simão Francisco de Almeida, during the child’s baptism on 25 June 1820.36 It is likely that the possibility of manumission for themselves and their children helped keep some enslaved women from rebelling against their masters. Meanwhile, the affection masters demonstrated for the offspring of their captives reinforced the paternalism of slave societies.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Portuguese colonial government took measures to ameliorate the conditions of the enslaved when other European powers had already abolished slavery in their colonial territories (). In 1853, the Governor of Angola, Visconde de Pinheiro, issued an ordinance forbidding masters from punishing captives. Instead, the document required that masters treat their captives “humanely” by handing them over to the police for correction.37 As of 1855, captives could denounce abusive masters to the Junta Protetora de Escravos e Libertos or Board for the Protection of Slaves and Freed Africans. The Junta Protetora played an important role in rescuing mistreated captives; however, the institution only intervened in extreme cases after confirming that the life of the enslaved person was in danger (). In addition, on 26 July 1856, Sá de Bandeira, President of the Overseas Council in Lisbon, ordered that children born from enslaved women were to be free from that date onwards. Nevertheless, the new law also established that they had to serve the masters of their mothers until the age of twenty ().

Mothers sometimes could save enough through their work to purchase their manumission and that of their children. For instance, On 25 November 1857, Antónia Francisca paid 40,000 réis to her mistress, Dona Maria Rodrigues da Silva, to emancipate herself and her son, Pedro. Dona Maria declared to have accepted the offer because of the good services Antónia had provided over the years.38 It is likely that Antónia was a skilled enslaved woman who worked outside her mistress’ household and, therefore, had more possibilities of making an income. The purchase of hers and her son’s manumission should only have been possible after many years of hard work. Most mothers were likely unable to purchase their own and their children’s manumissions.

Despite the measures passed during the second half of the nineteenth century to alleviate the condition of slavery, the constant flight of captives and the growing number of mutolos, as communities of runaway slaves were known in Angola, indicate that the laws did not obtain the desired result. Among the runaways were enslaved children who escaped with their parents, alone or in the company of other adult slaves. Although it was believed that women were less likely to run away because they would not leave their children behind, the documentation produced in Luanda shows that mothers escaped and took their children with them (). On 3 July 1859, the enslaved women Maria and Luiza and the enslaved girl Marcelina ran away from their master Luiz António de Freitas in Luanda. Luiza brought her two children, a cria de peito and a six-year-old whose sexes and names were not identified. On 11 July, Freitas announced the escape of his captives in the local gazette, offering compensation to anyone who captured them and threatening those who helped the runaways.39

Captives who formed families and were supposedly more integrated also resorted to flight, carrying their children with them. On 1 October 1868, João Nganga and Maria ran away from their master’s farm in the Luanda interior with their four children, three girls and a boy. The couple and their children were joined by another enslaved woman named Antónia.40 Children also escaped individually, as was the case of ten-year-old Joaquim, who had run away when his master, a certain Guilherme from Portugal, registered him in 1855.41 When in 1862, Dona Isabel Maria Alves Barbosa registered the twelve-year-old enslaved boy João, she noted that he had escaped from her house in Luanda.42 Studies by Daniel B. Domingues da Silva and José C. Curto indicate that many captives working in Luanda during the mid-nineteenth century originated from areas near the coast and were Kimbundu, Kikongo, and Umbundu speakers (Domingues ; ). Therefore, it is possible that some children escaped, hoping to return to their communities or reach one of the many mutolos near Luanda. Announcements of runaway slaves abounded in the local gazette, the Boletim Oficial de Angola, until the total abolition of slavery in the colony.

7. Conclusions

After the era of slave exports, slavery expanded in Luanda to support the production and trade in tropical commodities and meet the needs of the growing urban population. The enslaved performed domestic work in households, specialized in artisan crafts, and cultivated the land on arimos and plantations in the interior. Some of these captives were children who were born into slavery or were captured as a result of warfare, kidnapping, and attacks from bandit groups. Masters might have purchased captive children because they were cheaper and because they believed that children were easier to assimilate, train, and control. Despite their young age, masters expected enslaved children to perform the same work required of enslaved men and women. Enslaved children also faced similar violence, including branding, physical punishment, and psychological and sexual abuse. Not surprisingly, they, too, resorted to flight, alone or accompanied by their parents and other adult captives. Sometimes, masters granted manumission to enslaved children as gratitude for the good service and exemplary behavior of their mothers. The practice might have prevented rebellious actions from enslaved women who tolerated abuse in the hope of seeing their children manumitted. In the end, the care some masters demonstrated for the offspring of their captives reinforced the paternalism of slave societies.

Funding

The research for this paper was funded by an institutional grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Tracy Lopes and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Vanessa S. Olivera. Slave Registers. Available online: www.slaveregisters.org (accessed on 17 December 2023), ID SR000587. |

| 2 | For the register of António Francisco, see Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR000586. |

| 3 | The term “legitimate” commerce was adopted by Europeans to define the trade in tropical commodities in opposition to the trade in captives. However, it does not account for the fact that tropical commodities were produced with slave labor and that slavery continued to be legal in Africa, as well as the trade in captives to supply the domestic market. The term also neglects the fact that commodities other than slaves (including ivory, wax, and palm oil) had been exported from Africa before the early nineteenth century. For a discussion of the term, see (). |

| 4 | On the illegal slave trade from Angola, see (, ; ; , ; ). |

| 5 | Boletim Oficial de Angola (BOA), n. 85, 24 April, 1847, pp. 3–5. |

| 6 | See the case of Captain Cunha in (). |

| 7 | Bispado de Luanda (BL), Livro de Batismos Conceição (Sé Velha) 1812–1822 e Remédios, 1816–1822, fl. 37v. |

| 8 | BL, Livro de Batismos Conceição (Sé Velha) 1812–1822 e Remédios, 1816–1822, fls. 93 and 197. |

| 9 | BL, Livro de Batismos Conceição (Sé Velha) 1812–1822 e Remédios, 1816–1822, fl. 16. |

| 10 | BL, Livro de Batismos Conceição (Sé Velha) 1812–1822 e Remédios, 1816–1822, fl. 191. Some free men sent their offspring from enslaved women to be educated in Brazil. See (, p. 137). |

| 11 | BOA, n. 130, 4 March 1848, p. 1. |

| 12 | Although the transatlantic slave trade largely absorbed young men, recent studies demonstrate that the shipment of women and children to the Americas was higher than previously assessed. See (, ). |

| 13 | Olivera, “Slave Registers”. Available online: www.slaveregisters.org (accessed on 19 January 2024). |

| 14 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR002485. |

| 15 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR002672. |

| 16 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR003525. |

| 17 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR005247. |

| 18 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR002573. |

| 19 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR001239, SR001230, SR001242. |

| 20 | BOA, n. 146, 15 July, 1848, p. 4; BOA, n. 149, 5 August, 1848, p. 4; BOA, n. 150, 12 August, 1848, p. 1. |

| 21 | BOA n. 145, 8 July 1848, p. 3. |

| 22 | BOA n. 149, 5 August 1848, p. 4. |

| 23 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR002133. |

| 24 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR003816. |

| 25 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR001579. |

| 26 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR003760. |

| 27 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR001995. |

| 28 | BOA, n.308, 23 August 1851, p. 4. |

| 29 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR006191, SR006192, SR006193, SR006194, SR006195, SR006196, SR006197, SR006198, SR006199, SR006200, SR006201, SR006202, SR006203. |

| 30 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR002722 and SR002723. |

| 31 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR001053 and SR001054. |

| 32 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR002836 and SR002835. |

| 33 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR002698 and SR002700. |

| 34 | BL, Livro de Batismos Conceição (Sé Velha) 1812–1822 e Remédios, 1816–1822, fl. 72. |

| 35 | BL, Livro de Batismos Conceição (Sé Velha) 1812–1822 e Remédios, 1816–1822, fl. 197. |

| 36 | BL, Livro de Batismos Conceição (Sé Velha) 1812–1822 e Remédios, 1816–1822, fl. 147v-148. |

| 37 | BOA, n. 419, 8 October 1853, pp. 1–2. |

| 38 | Arquivo Nacional de Angola, Códice 5613, Carta de Liberdade, 25 November 1857, fl. 19. |

| 39 | BOA, n. 715, 11 June 1859, p. 14. |

| 40 | BOA, n. 49, 5 December de 1868, p. 587. |

| 41 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR001200. |

| 42 | Oliveira, “Slave Registers”, ID SR003837. |

References

- Alexandre, Valentim, and Jill Dias, eds. 1998. O Império Africano 1825–1990. Lisbon: Estampa, p. 370. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Kathleen M. 1996. Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Candido, Mariana P. 2006. Enslaving Frontiers: Slavery, Trade and Identity in Benguela, 1780–1850. Ph.D. dissertation, York University, Toronto, ON, Canada; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Candido, Mariana P. 2011. African Freedom Suits and Portuguese Vassal Status: Legal Mechanisms for Fighting Enslavement in Benguela, Angola, 1800–1830. Slavery & Abolition 32: 447–59. [Google Scholar]

- Candido, Mariana P. 2012. Concubinage and Slavery in Benguela, ca. 1750–1850. In Slavery and Africa and the Caribbean: A History of Enslavement and Identity since the 18th Century. Edited by Nadine Hunt and Olatunji Ojo. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, pp. 66–84. [Google Scholar]

- Candido, Mariana, Mariana Dias Paes, and Juelma de Matos Ngala. 2023. História e Direito em Angola: Os processos judiciais do Tribunal da Comarca de Benguela (sécs. XIX-XX). Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory Research Paper Series 8: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Candido, Mariana P., and Vanessa S. Oliveira. 2021. The Status of Enslaved Women in West Central Africa, 1800–1830”. African Economic History 49: 127–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, Carlos Alberto Lopes. 1972. Ana Joaquina dos Santos Silva, industrial angolana da segunda metade do século XIX. Boletim Cultural da Câmara Municipal de Luanda 32: 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Curto, José C. 1988. The Angolan Manuscript Collection of the Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, Lisbon: Toward a Working Guide. History in Africa 15: 163–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto, José C. 1999. The Anatomy of a Demographic Explosion: Luanda, 1844–1850. International Journal of African Historical Studies 32: 381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto, José C. 2002. As If From A Free Womb’: Baptismal Manumissions in the Conceição Parish, Luanda, 1778–1807. Portuguese Studies Review 10: 26–57. [Google Scholar]

- Curto, José C. 2003. The Story of Nbena, 1817–1820: Unlawful Enslavement and the Concept of ‘Original Freedom’ in Angola. In Trans-Atlantic Dimensions of Ethnicity in the African Diaspora. Edited by Paul E. Lovejoy and David V. Trotman. London: Continuum, pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Curto, José C. 2017. Re-thinking the Origin of Slaves in West Central Africa. In Changing Horizons of African History. Edited by Awet A. Weldemichael, Anthony A. Lee and Edward A. Alpers. Trenton: Africa World Press, pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Curto, José C. 2020. Producing ‘Liberated’ Africans in mid-Nineteenth Century Angola. In Liberated Africans and the Abolition of the Slave Trade, 1807–1896. Edited by Richard Anderson and Henry B. Lovejoy. Rochester: University of Rochester Press, p. 247. [Google Scholar]

- Curto, José C., and Raymond R. Gervais. 2001. The Population History of Luanda during the late Atlantic Slave Trade, 1781–1844. African Economic History 29: 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curto, José C., Frank J. Luce, and Catarina Madeira Santos. 2015. The Arquivo da Comarca Judicial de Benguela: Problems and Potentialities. Africana Studia 25: 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, Daniel B. Domingues. 2011. Crossroads: Slave Frontiers of Angola, c. 1780–1867. Ph.D. dissertation, Emory University, Atlanta, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, Daniel B. Domingues. 2013. The Atlantic Slave Trade from Angola: A Port-by-Port Estimate of Slaves Embarked, 1701–1867. The International Journal of African Historical Studies 46: 105–22. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, Daniel B. Domingues. 2017. The Atlantic Slave Trade from West Central Africa, 1780–1867. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Almada, José. 1932. Apontamentos Históricos sôbre a Escravatura e o Trabalho Indígena nas Colónias Portuguesas; Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional, pp. 40–41.

- de Castro Lopo, Júlio. 1948. Uma rica dona de Luanda. Portucale 3: 129–38. [Google Scholar]

- de Lima, José J. Lopes. 1846. Ensaios Sobre a Statistica das Possessões Portuguezas; Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional, Volume III, p. 203.

- de Oliveira, Mário António Fernandes. 1963. Para a História do Trabalho em Angola: A escravatura luandense do terceiro quartel do século XIX. Boletim do Instituto do Trabalho, Providência e Ação Social 2: 48. [Google Scholar]

- Douville, Jean Baptiste. 1832. Voyage au Congo et dans l’intérieur de l’Afrique équinoxale...1828, 1829, 1830. Paris: J. Renouard, vol. I, p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Eltis, David. 1987. Economic Growth and the Ending of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Eltis, David, and David Richardson. 2010. Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- Eltis, David, and Stanley L. Engerman. 1992. Was the slave trade dominated by men? Journal of Interdisciplinary History 23: 237–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltis, David, and Stanley L. Engerman. 1993. Fluctuations in sex and age ratios in the transatlantic slave trade, 1663–1864. Economic History Review 46: 308–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Roquinaldo A. 1999. Brasil e Angola no Tráfico Illegal de Escravos. In Brasil e Angola nas Rotas do Atlântico Sul. Edited by Selma Pantoja. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand, pp. 143–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, Roquinaldo A. 2003. Transforming Atlantic Slaving: Trade, Warfare, and Territorial Control in Angola, 1650–1800. Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA; p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, Roquinaldo A. 2008. The Suppression of the Slave Trade and Slave Departures from Angola, 1830s–1860s. In Extending the Frontiers: Essay on the New Transatlantic Slave Trade Database. Edited by David Eltis and David Richardson. New Haven: Yare University Press, pp. 313–34. [Google Scholar]

- Glymph, Thavolia. 2008. Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood, Linda M. 2002. Portuguese into African: The Eighteenth-Century Central African Background to Atlantic Creole Cultures. In Central Africans and Cultural Transformations in the American Diaspora. London: Cambridge University Press, pp. 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kananoja, Kalle. 2010. Healers, Idolaters, and Good Christians: A Case Study of Creolization and Popular Religion in Mid-Eighteenth Century Angola. International Journal of African Historical Studies 43: 443–65. [Google Scholar]

- Karasch, Mary C. 1967. The Brazilian Slavers and the Illegal Slave Trade, 1836–1851. Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Keefer, Katrina H. B. 2019. Marked by fire: Brands, slavery, and identity. Slavery & Abolition 40: 659–81. [Google Scholar]

- Law, Robin. 1995. Introduction. In From Slave Trade to ‘Legitimate’ Commerce: The Commercial Transition in Nineteenth-Century West Africa. Edited by Robin Law. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy, Paul E. 2004. Concubinage in an Islamic Society. In Slavery, Commerce and Production in the Sokoto Caliphate of West Africa. Trenton: Africa World Press, pp. 66–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy, Paul E. 2012. Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa, 3rd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy, Paul E. 2014. Pawnship, Debt, and ‘Freedom’ in the Atlantic Africa During the Era of the Slave Trade: A Reassessment. The Journal of African History 55: 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Joseph C. 1982. The Significance or Drought, Disease and Famine in the Agriculturally Marginal Zones of West-Central Africa. Journal of African History 23: 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, Joseph C. 1988. Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730–1830. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, p. 388. [Google Scholar]

- Nwokeji, G. Ugo. 2011. Slavery in Non-Islamic West Africa, 1420–1820. In Cambridge World History of Slavery. Edited by David Eltis and Stanley Engerman. New York: Cambridge University Press, vol. 3, p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, Vanessa S. 2014. Trabalho escravo e ocupações urbanas em Luanda na segunda metade do século XIX. In Em torno de Angola: Narrativas, identidades e as conexões atlânticas. Edited by Selma Pantoja and Estevam C. Thompson. São Paulo: Intermeios, pp. 249–75. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, Vanessa S. 2016. Slavery and the Forgotten Women Slave Owners of Luanda (1846–1876). In Slavery, Memory and Citizenship. Edited by Paul E. Lovejoy and Vanessa S. Oliveira. Trenton: Africa World Press, pp. 129–48. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, Vanessa S. 2018. Donas, pretas livres e escravas em Luanda (Sec. XIX). Estudos Ibero-Americanos 44: 447–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Vanessa S. 2020. Baskets, stalls and shops: Experiences and strategies of women in retail sales in nineteenth-century Luanda. Canadian Journal of African Studies 54: 419–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Vanessa S. 2021. Slave Trade and Abolition: Gender, Commerce, and Economic Transition in Luanda. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, Vanessa S. 2022. Mulheres escravizadas e resistência a escravidão em Luanda no século XIX. Portuguese Studies Review 30: 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, Vanessa S. 2023. Dona Ana Joaquina dos Santos Silva: A Woman Merchant of Nineteenth Century Luanda. In General History of Africa: Africa and Its Diasporas. Edited by Vanicleia Silva Santos. Paris: Unesco, vol. X, pp. 913–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pantoja, Selma. 2008. Women’s Work in the Fairs and Markets of Luanda. In Women in the Portuguese Colonial Empire: The Theatre of Shadows. Edited by Clara Sarmento. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, Claire C., and Martin A. Klein, eds. 1997. Women’s Importance in African Slave Systems. In Women and Slavery in Africa. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, Manisha. 2016. The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition. New Haven and London: Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, Randy J. 2004. The Two Princes of Calabar: An Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Odyssey. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez, Francisco Travassos. 1861. Six Years of a Traveller’s Life in Western Africa. London: Hurst and Blackett, vol. II, p. 277. [Google Scholar]

- Vansina, Jan. 2001–2003. Portuguese vs Kimbundu: Language Use in the Colony of Angola (1575–c.1845). Bulletin des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences d’Outre-Mer 47: 267–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, Douglas L. 1996. Angolan Woman of Means: D. Ana Joaquina dos Santos e Silva, Mid-Nineteenth Century Luso-African Merchant-Capitalist of Luanda. Santa Bárbara Portuguese Studies 3: 284–97. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).