2. Surname History and Name Change

2.1. Development from Surname to Family Name

Before I address the issue of name change for compatriots whose ancestors lived in slavery, it seems appropriate to summarize the history of surnames in the Netherlands

7. This will include information on name change under the Name Act in general.

At some place and time in history, when surnames were written down in documents to identify people, for example in contracts and for tax purposes, they became more or less hereditary. Starting in the Middle Ages, the surname wave flowed across the country from the south, present-day Belgium, swirled from crowded cities into the calm countryside and, a few centuries later, also leaked through backward regions. And at the same time, the surname system evolved in social strata from rich to poor, or from being somebody to nobody, until finally everybody was allowed to exist under state control. The result is that every Dutch citizen is registered with a family name, which is confirmed by his or her identity card or passport.

The development of the surname system took centuries, and while naming after parents, giving nicknames and letting others know where you live or come from by your name may have been a widespread oral tradition, the process was in fact part of the rise of written culture. Subsequently, the church administration also benefited from the identification of members. Genealogists find links to previous generations before the introduction of the Civil Registry especially in these.

Well considered, it is curious that in the present time one walks around with an old name that once belonged to an ancestor one knows nothing about. Those interested in family history can go back a long way in time by genealogical means, but if one even gets to those responsible for the name in question, the naming motive is often still guesswork.

Someone with a name like Smit will understand that he or she bears this name because (along the father’s family line) a distant ancestor was a smith by trade. But the socioonomastic context is unclear. Generally, people assume that their ancestors chose their names themselves. They are not aware that their family names are the result of a long period of nicknaming and that those names were actually given. Nicknames can be good or bad. Some Dutch families literally do have the name De Goede (The Good) or De Slegte (The Bad). Thus, with their inseparable name, persons named De Slegte still confirm the negative image once attributed to an ancestor for one reason or another. In our time, by the way, the family name De Slegte has been established by a well-known retail chain of second-hand books and remnants of publishing houses that is not doing so badly.

Onomastic research reveals that with regard to surnames, there are several categories of naming motives. The most common surname types are those referring to toponyms and those derived from first names, called patronymics, and in many fewer constructions metronymics, if a female first name is the source. Then there are many occupational names. These, like the profusion of patronyms, emphasize the patriarchal mark on society in the past through their masculine word forms. Also innumerable are the surnames that indicate outer or inner personal characteristics. Contemporary namesakes may even have names that may indicate physical defects or peculiarities, which is especially inconvenient because the offspring with that name are no longer blind or deaf and do not limp or stutter.

Apart from quite transparent surnames, whose meaning can be guessed at, there are also quite a few names that are not easily interpreted. Sometimes these are, for example, patronymics to nowadays unknown given names or they are adaptations of immigrants’ foreign-language names.

A surname can be a hook of the rod for those who want to fish for their genealogical family history, but for most of us, a family name is a name that simply belongs to us, and that is all there is to it. If you have the family name Visser ‘fisher’ and have never caught a fish, you do not need to feel awkward. Still, the image of a name and its connotations lurks around unconsciously and sometimes consciously. Many people have only a foggy view on family names as a mystical or mysterious phenomenon. The lack of scholarly interest in proper names does not help to clear the view.

2.2. Misconceptions about Family Names

In the Netherlands, children are still incorrectly taught in school that they owe their Dutch family name to Napoleon

8. They were told that there are odd names among them because they were adopted by provocative patriots at the time. Unfortunately, these seemingly heroic patriots only made fools of themselves, and their descendants still have to live with those funny names. An oft-cited example of such a name is the family name Naaktgeboren ‘born naked’. But Naaktgeboren originally was a nickname that existed already as a surname in the 17th century

9 (

Figure 2).

What the textbooks actually refer to is the introduction of civil registration under French rule in 1811, which required everyone to have a fixed family name. But it is like teaching that before Christ there was no time. In fact, almost all of the inhabitants of the Netherlands used surnames before 1811. That is, in some remote and sparsely populated areas, an active patronymic system still sufficed. These patronymics changed from generation to generation, as is still common in Iceland. Also, many residents across the country were known by a string of three names: a first name, a patronymic and a surname, usually already a hereditary family name. The use of a three-name structure ended rather abruptly with the introduction of the Civil Registry. Only first names and family names were noted. To create fixed family names, many patronymics were registered as such.

In 1811, heads of households not yet known by a family name were expressly invited to adopt or confirm one for themselves and their families at a town hall in preparation for registration with the Civil Registry. It turns out that mainly in rural areas of the northeastern provinces, good use was made of the name adoption registers. In Amsterdam and other places with Jewish communities, practically only Ashkenazic Jewish residents showed up. They took the opportunity to adopt so-called civil names in addition to their Jewish, Hebrew-oriented names. This was seen as an important emancipatory step in the process of assimilation and recognition as full citizens.

The municipal agencies of the Civil Registry were maintained when the French withdrew in 1813 and the Netherlands became an independent kingdom. The government had definitively taken over from the clergy the registration of the joyous facts of birth and marriage and the sad declaration of death.

2.3. Family Names and Spelling

It is noteworthy that family names were fixed in a hereditary spelling form, which often deviates from the spelling that would be common today. Because the standard spelling formulated in those days had not yet penetrated to all layers of the population and the civil service also still had its own habits, the spelling was rather varied. An archaic form became even more of a feature of family names thanks to several spelling reforms from which proper names were excluded. From a geographical point of view, family names spelled in old-fashioned ways are particularly characteristic of the Southern Netherlands, i.e., contemporary Flanders and Limburg. Surnames were recorded there earlier than in the north and the name bearers and clerks were faithful to the spelling they were used to.

An example of a general spelling adjustment is that of the consonant [x] in the noun knecht ‘servant’. The spelling reform of 1863 stipulated that words in which this consonant appears in the place of knecht should be written with -ch- instead of -g-. However, as far as the family name derived from it is concerned, the name form Knegt is by far in the majority.

The family name De Vries is the third Dutch name in quantity after De Jong and Jansen, and this name is the number one name in Amsterdam, from which it can be simply concluded that very many Frisians migrated to the capital. The spelling with a V suggests that De Vries is pronounced with a voiced V, but the province is now called Friesland and its inhabitants are Friezen with a voiceless F. The family name should now be De Fries or, in Frisian, even De Frys (Friesland is Fryslân), but that name form does not occur.

2.4. Name Change under Strict Name Law

The strictness of the family name system is anchored in name legislation. Family names have to be copied from generation to generation, exactly as they had been adopted by the Civil Registry since 1811. But gradually some names were legally allowed to be changed, the procedure of which was sealed with a Royal Decree. Thus, for instance double names were created among the bourgeoisie when it was shown that the name of mother’s family was in danger of becoming extinct. Replacement of one name by another, if it did not concern changing a parents’ name into another parents’ name, became possible when the image of such names was recognized as burdensome to one’s well-being. Those names were formally specified as being indecent or derisory. Later, the category of very common family names, which do not have much distinctiveness anymore, was also added.

The processing of a name change application is centralized, and the application is reviewed by a department of the Ministry of Justice

10. If you have a name that is not classified as indecent, ridiculous or too common, there is one more way to get rid of it. You will then need to provide a written opinion from a psychiatric expert advocating name change for your mental health. For example, nasty family circumstances could be a reason to want to distance yourself from your family and take this rigorous step. Recently, name law has been accommodated by allowing victims of abuse and violence within family circles to change their names free of charge without having to show expert attestation. However, there must be a criminal conviction or an award of benefits from the Violent Crime Compensation Fund.

2.5. Changing Indecent Names

When a name change is allowed, the choice of a new name is also patronized. The new name must meet several conditions to be authorized. To avoid the possibility of usurpation, i.e., unwanted identification with a (prominent) family, it should really be a new name and not an existing name. However, the new name must be recognizable as a Dutch name. Of course, one name of shame should not be replaced by another embarrassing name. A slight change in the name to be changed is promoted, but creativity is usually valued. The expense for such a procedure at the Bureau Justis is currently EUR 835. Until the mid-1990s, a name change had to be announced in the Official Gazette, but in recent decades this is no longer carried out to protect privacy.

To get an idea of the types of changes, some examples are in order. A well-known so-called indecent name is the family name Poepjes. Poepjes in itself is not indecent in origin, as practically no changed name qualifies for this qualification, but the association with

poep ‘poop’ has turned this patronymic into a shameful name (

Figure 3). Poepjes is mostly a Frisian family name and probably a more western variant of Popken, a diminutive of the common Dutch and German form Poppe, in the Dictionary of American Family Names explained as a nursery name or a short form of a Germanic personal name such as Bodobert

11. According to the reference years 1947 and 2007 in CBG Family Names, Poepjes has decreased by 50% during this period from 563 to 281 name bearers. CBG Family Names has 27 new names from former families with the name Poepjes, five of which begin with

Poe- and another seven with

Po(o)r, of which six are with

Po(o)rt ‘gate’. Most of them have a toponymic appearance. Twelve new names are constructed with the typical Frisian suffixes

-ma,

-stra or

-inga. Another possible explanation for the name presents itself with the name change to Velinga. This family was motivated by the synonomy of

poepe, from German

Pupe, and

veling, someone from East and Westphalia, as vernacular words for German seasonal workers

12.

An example of a common occupational name that has additionally acquired sexual connotations is the name Naaijer, from the verb naaien ‘to sew’, for a tailor. This verb is also one of the slang words for copulating, and therefore Naaijer has been changed by at least five families.

The fact that more than 25 families named Klootwijk have changed their name shows not only that dirty words in place names will not be condoned but also that contemporary mockery outweighs the connection through a name with prominent ancestors. Lumbered with the family name Klootwijk, you may be related to the owners of the knightly mansion Clootwijck at Almkerk. In many of the 25 name changes, the noun

wijk ‘settlement, district’ returns in the new pseudo-toponymic construction, e.g., Van Cootwijk, Kloosterwijk, (Van) Kootwijk, Korewijk, (Van) Kroonwijk, Rooswijk and Slootwijk

14. A branch has also revived the medieval spelling form Van Cloetwijck.

The replaced taboo word is kloot, not as intended in the proper name as a relict of an ancient personal name or with the meaning ‘globe’, but in the plural kloten with the meaning bollocks or testicles. For a real asshole or dickhead, the Dutch use the noun klootzak ‘scrotum’. Since this swearword is also shortened to zak ‘sack’, it has also been allowed in the past to change the family name Zak to a more bearable name. However, thanks to immigration, the number of bearers of the foreign surname Zak has increased in the Netherlands. Zak in the meaning ‘sack, bag’ is a part of several Dutch names such as Wolzak ‘wool bag’, Gortzak ‘groats sack’, Peperzak ‘pepper sack’ and Hoppezak ‘hop sack’.

2.6. Guidelines for Constructing New Names and the Limitations

To change a name, a small modulation can simply be applied by adding a diaeresis. For example, the family name Piest has been changed to Piëst to emphasize how this presumably German-origin name should be pronounced. Piest could otherwise be understood as the third person singular of the verb piesen ‘to piss’. But for a branch of the family Piëst, this addition was not sufficient. Another name change with Royal Decree from Piëst to Piejest followed. Even if in some cases it makes sense to stay close to the changed name, should this necessarily be recommended? Moreover, it goes against the premise that the new name should pass for a Dutch one. If you do not know that Tjelpa is a reshuffling of Platje, which was changed because of its association with platjes ‘pubic lice’, you would think it is a foreign name. Rio from Riool (riool ‘sewer’) is an easy and understandable name change, but it does not provide a Dutch-like name. Rio is a Spanish and Portuguese noun for ‘river’. In the world, it is a wide-spread surname, but in the Netherlands, it was not yet known.

In such cases, the requirement of constructing a Dutch-like name seems to have been toned down to the ability to pronounce a name. Indeed, by extension, it is still possible for immigrants to adapt a name that is unpronounceable to the Dutch as it benefits their integration. For example, Engee was transformed from Ng, Krezmien from Krzemien, Hantink from Hnatiuk and Zwerk from Cvrk. The last two have become truly Dutch names.

Some immigrants who want to integrate optimally have managed to come up with a completely invented new name. One of them is the family name Terphuis, chosen by a refugee who refers with his new name to a (safe) house on a

terp, a Frisian noun for a settlement on a (refuge) hill in the period before dikes were built to protect the low land from the sea water. Terphuis is a name in the line of the common Frisian family name Terpstra

15.

Adaptations of foreign names used to be commonplace in earlier times, and that has also resulted in indecent or mocking names that would qualify for name change. The French name Picard, for someone from Picardy, has been interpreted as Piekhaar ‘spiky hair’, the form of which has also been spelled as Pikhaar, which unfortunately can be explained as ‘pubic hair’ (of men: vernacular pik ‘penis’). In 1988, a namesake was allowed to change this name to Pinkhaar, which could be read as ‘hair of a pinky’ (pink = ‘little finger, pinky’). A small branch of the Scottish Abercrombie family is known in the Netherlands by the name Apekrom (‘crooked as a monkey’).

These pre-Napoleonic distortions cannot be corrected because they entered the Civil Registry as such. However, this principle is in contradiction with a recent amendment of the name law in favor of Frisian names. As a consequence of the recognition of Frisian as an independent language, this amendment provides Frisians in the province of Friesland with the opportunity to convert their (hybrid) Dutch-Frisian name into an authentic Frisian form. But such a name change is only permitted if it can be shown that a Frisian form actually preceded the current one.

That is precisely what is problematic in Friesland, where the patronymic system was still in effect before 1811. The names of most rural residents were new when they entered the Civil Registry. When the opportunity for a name change is seized, it mainly concerns the conversion of a Dutch ij into a Frisian y, for instance IJpma into Ypma, Dijkstra into Dykstra, which could be demonstrated because in the past the ij was often written without dots; the ij and the y are in fact the same in Dutch names.

Would anyone have been able to change the name De Vries to De Frys? The entire adjustment to please the Frisians does not take into account the fact that spelling was not standardized in the past and any name could appear in many spellings, which is the reason for the enormous spelling variation in names today.

2.7. Outstanding Individual Creations and Negation

Name changes involving names that cannot in themselves be considered abject are usually undertaken by strong-willed loners. To mention just two of them: Duizendschoon and Van der Lijstersangh. The surname Duizendschoon has been borrowed from the generic name of a flower that translates as Sweet William in English and in Dutch is a compound of duizend ‘thousand’ and schoon ‘beautiful, fair’. Van der Lijstersangh can be translated as ‘From the Thrush Song’, indicating a place of residence where thrushes sing, to be considered a variant of the common name Vogelzang ‘Birdsong’. Lijstersangh is an antiquated spelling of lijsterzang. These new names can be called real creations, adopted by individuals who needed an appropriate name.

A notable newcomer is the name De Naamloze ‘The Nameless One’. It is impossible not to have a name, but somebody persisted in adopting a unique name for herself by which she expresses not having a name. The Secretary of State initially did not approve of her choice, but the woman in question defended her motivation in court. She stated that she had experienced a spiritual rebirth. Since this transformation she no longer exists as a civil person and that was why she wanted to get rid of her name. The judge ruled that this name had to be accepted, because it did not yet exist, it was Dutch and it was not an indecent or offensive name

16.

Madame de Naamloze is not the first to distinguish herself with a proper name that contradicts in content the identifying function of naming. Who are you when your name is Niemand (‘nobody’)? Are you perhaps affiliated with those who bear the family name Niemantsverdriet ‘no one’s grief’? The fairly common surname Zondervan means ‘without surname’, as the prepositon van ‘from’ is characteristic for many Dutch surnames. This surname that is a surname of someone who does not have a surname originated at a time when many did have a surname and those without van were thus embarrassed and surnamed Zondervan.

The essentially ironic name change of an existing family name into De Naamloze calls for reflection on the phenomenon of proper names. Does one need to have a name? How did people know each other in the days when there was no written word? Whenever and wherever, from the beginning, the nicknames must have forced themselves upon the people. Read Homer for the epithets.

We should also realize that proper names such as surnames and also place names have gone through a lengthy process to be retained in a fixed form as a relic by us in modern times. They are just names. There is no actual connection to content or sense anymore

17. It is interesting to observe that even contemporary individual nicknames become surnames without the naming motive still playing a role.

Family names serve primarily in an established system by which the population can be monitored. You need a permanent last name on an ID card or passport. Periodic phasing and alternation with respect to surnames are no longer formally accepted practices in the Western world, except for the adoption of a spouse’s name by his spouse in some societies

18. Legally though, it is easier to change, for instance, a pseudonym into a real family name in countries with an English law tradition. Bob Dylan, who was born as Robert Zimmerman, actually now has the family name Dylan and thus his children are also named Dylan

19.

3. Name Aquisition by Freedmen in Suriname

3.1. Assigned Slave Names

In the shameful past, whole communities were enslaved and cruelly kidnapped from their African native soil to serve Dutch and other West European colonists in the Dutch colonies for the benefit of their prosperity and the Dutch economy. Slaves were no civilians. No surnames were assigned to them, only slave names that could be considered singular personal names, although a slave name may have consisted of two (given) names. Those slave names showed hardly any traces of African origin. Upon embarkation in West Africa, no names were recorded and there was no writing culture in which they could be preserved. After disembarkation in Suriname, the abductees were assigned Western names.

The slave registers of the West Indies show a rich variety of personal names

20. Most slave names in the 19th century make a distinguished impression. In addition to traditional high-class English, Spanish, French, Dutch and German personal names, there are notable names referring to historical figures, such as Napoleon and Lucretia

21, and names that evoke a desired image such as Princess, Duchesse, Lapaix, Sansouci, Gracia, Cupido and Victorie. Also worth mentioning are geographical names such as Azia, China, Surinamia, Washington (also referring to George Washington, of course), Amsterdam and Rotterdam, and nickname-like names, which are not all favorable, such as Brilletje (‘small glasses’), Kardinaal (‘cardinal’), Mentor (‘mentor, tutor’), Flink (‘brave, firm’), Dwingeland (‘a forcing person’), Nooitgedacht (‘never thought of’), Welkom (‘welcome’), Weltevreden (‘well satisfied’), Winst (‘profit’), Geluk (‘luck, happiness’) and Ongeluk (‘unluck’).

3.2. Family Names Obtained by Manumission

Before slavery was abolished in 1863, many individuals with slave status were already freed or ransomed over the years. When they were manumitted, in due time they were also registered as civilians and therefore were assigned family names

22. Manumission often involved children who arose from the relationship of an owner and a slave woman. In the colonies, concubinage, the cohabitation of a European settler and his housekeeper, was the rule rather than the exception. As heirs or as money-earning craftsmen or merchants, freedmen themselves became slaveholders.

Whether there was blood relationship with the former owner or not, initially the name acquired often expressed interdependence anyway. In some cases, a possessive van, ‘of’, was simply put in front of the owner’s name. This led, for example, to the curious name form Van van de Vijver, with twice the preposition

van ‘of, from, at’ for someone who, before he was a freedman, belonged to Van de Vijver. In the latter habitational name, the preposition indicates where someone lived: at the

vijver ‘pond’

23.

Other names were partly or completely reversed: Vriesde from De Vries, Tdlohreg from Gerholdt. This kind of treatment of an existing name was also known in the Dutch East Indies. In these former Dutch colonies, such names affirmed a half-hearted recognition of blood relationship between settlers and their natural children by native women.

However, in Suriname, modifying existing names, or adding the preposition van, to create new names for dependent subjects was no longer tolerated several decades before the Emancipation of 1863. According to the Manumission Act of 1832, surnaming henceforth had to be a governmental matter. The adoption of names already known in Suriname was allowed only with the permission of the families concerned.

3.3. Family Names Obtained after the Abolition of Slavery

The vast majority of the slave population obtained family names at the Emancipation of 1863. Prior to that, so-called borderels were completed for each plantation for comparison with the slave registers kept by the government. The district commissioner and his secretary then visited the plantations to check the presence and health of the slaves listed on the borderels. The slave owners were financially compensated quite a bit per slave.

The borderels only contained slave names. Subsequently, personal names to be included in the Civil Registry were recorded in Emancipation Registers. Thus, the former slaves obtained a sometimes entirely new first name and a family name, which indeed had to be a family name, since in these matrifocal communities, a (grand)mother and her (grand)children were kept together by the same name. Family relationships could extend across several plantations, and namesakes in Paramaribo mostly involved relatives who had been sent to the capital for work or training. Escaped slaves and their descendants who lived as maroons in the interior, like the natives, did not obtain a surname by which they were incorporated into society until much later.

There was reportedly a festive mood when the officials arrived on the plantations in 1863. No more slavery. Civil rights were established. From then on, the descendants of the exploited and suppressed slave population became Dutch nationals with Dutch family names or with family names derived from other European languages. A few exhibit a name that traces back to African roots via the vernacular languages Sranan Tongo in Suriname and Papiamentu in the Netherlands Antilles.

3.4. Comparison with the Imposed Name Registration in the Netherlands under French Rule

The concept of surnaming is based on naming each other. Family names normally arise from surnames. Only twice in the naming history of the Netherlands have measures been taken to provide family names to entire population groups from one moment to the next, family names that had to be formed out of the blue. So that was in 1811 with the introduction of civil registration and 1863 with the Emancipation of fellow human beings who had lived in slavery.

However you look at it, in a way, these two situations are similar. They were both government issues. People who were not used to surnames for themselves had to make up family names on the spot. Everyone who showed up was practically illiterate. There are no testimonies, but we can assume that in 1811 the town clerks or the deputies of the French government had a finger in the pie when an applicant had to construct and choose a family name. Existing names served as models. In fact, in 1811, many common names were copied or made into new names. Many Frisians, as well as quite a few Jews, took some of the most familiar names such as De Jong and De Vries. Partly for this reason, they are certainly the most frequent Dutch family names today. These names were easy default choices. A frequently adopted name in Friesland is the topographical or habitional name Dijkstra for someone who lived by a dike or in a place named after its dike such as Surhuizumerdijk and Haskerdijken

24. New names were constructed with old suffixes, such as

-inga,

-ma and

-stra. The latter suffix is a contraction of Old Frisian

sittera, meaning ‘(of the) inhabitant(s) of’, and which in surnames is preceded by a place name. But in 1811, allusive occupational names were also created with

-stra, such as Schaafstra (

schaaf ‘block plane’) for a carpenter and Klompstra (

klomp ‘wooden shoe’) for a clogmaker.

Regarding name assignment in Suriname and the Antilles, the prevailing perception is that the freedmen had little say in their names and that they were assigned to them at random. The plantation owners allegedly submitted lists of names to the itinerant commissioners, which they simply copied into the registers. However, any such name lists are not archived.

In any case, one difference between the two situations is that in the year 1863, those involved had to take into account guidelines that were in line with the regulations that had by now been formulated in the Dutch name law. No indecent or ridiculous names were to be adopted, nor were names that were already familiar family names in the country. Whereas liberated American slaves were given common (English) names

25, in Suriname, this had to be dispensed with. No references to the names of the former owners and their representatives that might suggest an intimate connection should be obtained. In practice, however, names were also adopted that may not have been familiar in Suriname but were certainly already existing European names. Moreover, several existing names were taken apart to create new names from them.

If the commissioner and his secretary in 1863 did not simply copy the names that may have been handed to them by representatives of the plantation owners, they will at least, in cooperation with these administrators, have helped the new civilians in an advisory role. A patronizing attitude cannot be denied them. Assistance will also have been sought from the so-called black officer, the head of the enslaved community whose responsibilities on the plantation included the distribution of labor.

3.5. What Kind of Names Were Adopted on the Plantations in 1863?

In Suriname, the traveling officials were responsible for the adoption of thousands of names in little time. What kind of names were actually taken and approved? Perhaps an already familiar nickname would fit, or an appropriate occupational name, but most names had to be thought up from scratch.

A notable category within the concept of nicknaming concerns names denoting a virtue, derived from or composed with adjectives. Known in contemporary Holland are names of Surinamese descent such as Braaf (‘obedient’), Braafheid (‘obedience’), Braafhart (‘Braveheart’), Goedhart (‘good heart’), Grootfaam (‘great fame’), Tevreden (‘satisfied’), Weltevreden (‘well-satisfied’), Vreedzaam (‘peaceful’), Groeizaam (‘well growing’), Waakzaam (‘watchful’), Werkzam (‘diligent’), Deugdzaam (‘virtuous’), Getrouw (‘faithful’), De Getrouwe (‘the faithful’), Vertrouwd (‘trusty’), Trustfull (an English name: ‘reliable, trustworthy’), Zuinig (‘thrifty’), Zorgvol (‘caring’), Omzigtig (‘cautious, careful’), Moedig (‘brave’), Strijdhaftig (‘combative’) and Draaibaar (‘turnable, agile’). Some of these names were already known in the Netherlands, such as Braaf, Braafhart, Goedhart and Weltevreden, or were considered a variant of a traditonal name, such as Trouw and Moed en Deugd.

Desirable good traits or qualities were also expressed through nouns of abstract notions, for example, in the names Vrede (‘peace’), Vreugd (‘joy’), Welzijn (‘wellness’), Liefde (‘love’) and Hoop (‘hope’) and the compositions Hooplot (‘hope’ and ‘fate’) and Goedhoop (‘good hope’), Zuiverloon (‘pure wages’) next to Trouwloon (‘loyal wages’) in the Antilles, Koelbloed (‘cool blood’), Geduld (‘patience’), Promes (French ‘promesse’, English ‘promise’), Verbond (‘alliance’) and Vrijdom (‘freedom’). As names that were by no means intended to portray an ideal situation, the family names Crisis (‘crisis’) and Hongerbron (‘hunger source’) can be mentioned.

Some of these adopted names may refer to the process taking place. As such, the names Koningverander (‘king change’) and the variants Konigferander and Koningferander, Koningsgift (‘king’s gift’), Koningswet (‘king’s law’), Koningswil (‘king’s will’) and Koningverdraag or Koningsverdraag (‘king’s treaty’) are certainly to be noted. The family name Koningverdraag was adopted at the Berg and Dal plantation by the “creole mother” Charmantje Salomain, born in 1801, her daughter and two grandchildren. In 2007, there were 15 people with the name Koningverdraag living in the Netherlands and 17 with the variant Koningsverdraag. On Wikipedia we read: “Celebrations were organized during which King William III of the Netherlands was presented as a key figure and benefactor of the freed slaves”.

Other adopted names that can be mentioned in this context are the family names Borgerrecht (‘civil right’), Accord (‘agreement’) and possibly also the expressive names Nooitmeer and Nimmermeer (both ‘never again’)

26.

3.6. Family Names Derived from Place Names and Toponymic Creations

It is so striking that European place names were adopted as family names everywhere that one would think that the government representatives charged with the task carried an atlas so that random names could be designated in it for that purpose. That the soccer player Giorgio Wijnaldum’s ancestors themselves had a connection to the Frisian village can be highly doubted. Clarence Seedorf even has a German place name as his family name. It appears that the owners of the plantation, where his ancestors toiled, were Germans. May we assume that anyone else who attended the ceremony had some link to the Frisian village or to any of the various places named Seedorf in Germany? Or was Wijnaldum inventively selected simply because more adopted surnames contain the element of wijn ‘wine’? Compare Wijngaarde, Wijntuin, Boldewijn, Holwijn, Bergwijn, Wijnstein, Wijnhard and so on. Seedorf, by the way, is also a German family name.

On three different plantations, about a dozen people who had lived in slavery obtained the family name Oxford, possibly in reminiscence of a plantation named Oxford. Cambridge is another adopted family name, although no such plantation is known in Suriname. Several plantation owners were British, and therefore they were also slave owners until 1863, under the critical supervision of the British government, as slavery was abolished in England in 1833. The adopted family names on Hugh Wright’s sugar plantation Alliance were mostly English, for instance. However, on another plantation of this particularly active investor, the adopted names were not mainly English but a little bit of everything.

The preposition van, so common in Dutch habitational names, is missing from most toponymic surnames, probably because it recalled the property function it had acquired decades earlier in name formation at manumission. A certain systematics can sometimes be observed. At the plantation De Morgenster, where the family name Amsterdam was adopted, some other family names were derived from places around Amsterdam. A century later, the family names Amsterdam, Naarden, Baarn and De Rijp found their way to the Netherlands. At the plantation Ponthieu, by the way, the family name Madretsma was adopted as an inversion of Amsterdam. Madretsma is also a familiar name in the Netherlands these days.

Several plantation names served as denotatum, but not for those who resided on the plantation in question at the time. The plantation names are reminiscent of the names of country estates of the urban elite in the Netherlands. Dozens of plantation names were compounds with the elements of rust ‘rest, peace’ and lust ‘lust’ in the sense of pleasure to enjoy at a warande ‘pleasure garden’, idealizing country life, and the elements hoop ‘hope’ and zorg ‘care’, evoking the uncertainty of the bold step to start such a venture in the far West.

For creating new family names, existing names were tinkered with, and the vocabulary also lent itself to the creation of original compositions, usually of a pseudo-toponymic nature. For example, the element zorg was now also used to compose family names, some of which were permanently added to the Dutch name stock, such as Kortzorg (kort ‘brief’), Meerzorg (meer ‘more’) and Willemzorg, referring to King William III, Zorgvliet (vliet ‘stream’) and Burgzorg (burg ‘castle’), while Burgrust was another perennial creation. Meerzorg, by the way, was already an existing name of some plantations and country estates in the homeland. Zorgvliet was also a plantation name as well as the name of a royal mansion in The Hague, spelled Sorghvliet, now the official residence of the prime minister after being renamed Catshuis, after the poet Jacob Cats, who lived there in the 17th century.

The compositions Burgzorg and Burgrust do not make much sense, but burg is, of course, a common component of names. Burgrust unobtrusively fits into a cluster of names already known in the Netherlands such as Zeldenrust (zelden ‘seldom’), Holtrust (holt ‘wood’), Onrust (‘unrest’) and Nooitrust (nooit ‘never’), while Burgrust also reflects the name Rustenburg, a plantation name also adopted as a family name and already known as a topographical surname in the Netherlands. Rustenburg is a rather common house name in the Netherlands.

3.7. A Few More Observations Regarding the New Names

We must not forget that we are trying to understand names given 150 years ago, and as it is with most traditional surnames from a more distant past, the motivations were not recorded at the time of name adoption. We may observe some systematics here and there. Some names come in pairs, for example, Brijraam (‘knitting window’) and Haakmat (‘crochet mat’), and perhaps we can also recognize Blaaspijp (‘blowpipe’) and Doelwijt (‘target’) as such.

Seemingly contrary to regulations, seventeen names beginning with Bra-, fourteen with an E and eighteen with Sij- were adopted on the Dordrecht plantation, honoring the three owners, Brakke, Evertsz and Van Sijpesteijn. Who came up with the idea, we would like to know.

The commissioner will have allowed these names because this kind of reconstruction is not seen as deforming existing surnames in the way it was considered odious in manumission times. To be mentioned are the names Braafheid (see above), Brandveen and Brasdorp as family names exported to the Netherlands, while the adopted names Braambeek (the variant with the preposion van), Braambosch and Braskamp already existed here. Also, on this plantation, most new creations suggest a toponymic origin.

Another questionable naming practice took place at the La Prosperité plantation. All thirteen adopted family names begin with a P. The family name Pengel, originally a German name, was adopted here by a large family, and that is why more than 500 persons in the Netherlands currently have this name.

As the most common Surinamese family name in the Netherlands (

Bol and Vrij 2009), we also find a name beginning with a P, but this name comes from the plantation Onverwacht (‘unexpected’). It concerns the name Pinas with more than 1250 namesakes, which came to Suriname by a Jewish Dutchman of Spanish origin and was registered in 1863 by Martha Pinas and her 48 children and grandchildren.

Not all families were so large and close. However, due to the variety of names adopted, Pinas is in fact the only Afro-Surinamese name in the top ten of the most frequent Surinamese names in the Netherlands. The other names in the top ten are family names of the descendants of the British Indian and Javanese indentured laborers who succeeded the Afro-Surinamese enslaved. These population groups only adopted their names decades later, but they were able to use the repertoire of names from the countries of origin. What is felt to be particularly wrong with Afro-Surinamese family names is that they do not reflect African origins. This is a painful realization for descendants who share the traumatic experiences of their exploited forebears. Yet, we can also realize that very beautiful names have been adopted that many Dutch people, drawn from the Dutch clay, can be jealous of. Consider, for example, wealthy vegetation names such as Bloemenveld (‘flower field’), Cederboom (‘cedar tree’), Broodboom (‘bread tree’), Letterboom (‘letter tree’, a tropical species of mulberry tree characterized by black veins reminiscent of the letter S or snakes, hence also named snake tree, and from which walking sticks are made), Koningsbloem (‘kingflower’), Leliëndal (‘lily valley’), Leliënhof (‘lily court’), Olijfveld (‘olive field’), Druivendal (‘grape valley’), Druiventak (‘grapevine’), Lepelblad (‘spoon leaf’), Roosblad (‘rose leaf’), Rozenstruik (‘rose bush’), Groenbast (‘green bark’) and Klaverweide (‘clover meadow’). Were these names merely a reflection of the settlers’ paradise desires in line with their plantation names, such as Morgenstond (‘dawn, early morning hour’) and Goudmijn (Goldmine), which also happen to be adopted family names, or were the freedmen who acquired these names also happy or even proud of them? Whatever, since those gardens of Eden had to be created on the backs of enslaved human beings, the descendants of the victims have reasonable doubt about the good intentions of those fine names, which, they are convinced, also came out of that ironic mold. That their names significantly enrich the Dutch naming stock is not a valued measure.

4. Name Aquisition by Freedmen in the Netherlands Antilles

4.1. Different Circumstances, Different Names

The situation in the Netherlands Antilles or Dutch Caribbean differed from Suriname in that there were far fewer large-scale plantations. Nevertheless, many people lived in slavery. The port cities functioned as transshipment ports and markets, including for slaves shipped from Africa. On the island of Bonaire, slaves of the West Indian Company and, after 1792, of the government were put to work in the salt pans. These government slaves could be hired next to freedmen by individuals for all kinds of work, such as loading and unloading. There were estates everywhere where slaves served as servants, handymen, gardeners and farm laborers

27.

Two sources brought together in one website with a search function, made available by the National Archives of Curaçao, are important for understanding the situation at the time of the 1863 emancipation regarding the adoption of family names on Curaçao, the largest and most populous island in the Dutch Caribbean. First, there are the borderels, on the basis of which the slave owners received the amount of 200 guilders per slave as compensation. With that, we know that approximately 7000 slaves were emancipated in Curaçao. Then there are also notebooks in which the name adoptions were recorded, but those seem to be incomplete.

In May 1863, prior to the emancipation date of July 1, based on the borderels, the attendance and health of slaves in each district had to be checked by committees consisting of three delegates and a physician. In the city district of Willemstad, slaves were required to make their appearance at the council house where the committee sat daily. In the four outer districts, the committees went around the plantations and estates.

Also in May, slave owners in the districts were sent a form on which the names to be adopted were to be noted. The pre-printed text read:

Your honor is requested to enter below the family names to be adopted, the first names and the date of birth or presumed age of the slaves owned by you or under your administration.

In filling in the surnames, care should be taken not to give known family names to the slaves.

The registration must be done as much as possible family-wise, namely: the mother with her children under one and the same family name.

Your honor is also urgently requested to return this billet, duly completed, within eight days from today to

The District Commissioner in the… District (

Figure 4).

From the Third District, 73 forms were collected and bound into a 95-page notebook. Some forms list dozens of slaves to be freed, others only one or two. From the City District, a notebook has survived, in which 3145 name adoptions were recorded, signed on the last page by the district commissioner J.H. Schotborg. Each page has six columns to include the registration number, family names (the pre-printed word moedersnamen ‘mother’s names’ is crossed out), first names, date of birth or presumed age and remarks. The field for remarks contains the names of the former owners and is hard to read because it is filled in with pencil. Certificates were issued to the newly named.

This allows us to conclude that on Curaçao slaveholders were responsible for the assignment of family names. We do not know to what extent the slaves had a say in the family names assigned to them. However, many of these names have proved unsustainable, even if they belonged to large families.

4.2. Names from the Vernacular

The vernacular language in the Netherlands Antilles is Papiamentu, a Creole language that reflects many influences. The names adopted equally represent various spheres of influence. A list of the most common Antillean family names in the Netherlands illustrates this tellingly: Martina, Martis, Maduro, Zimmerman, Richardson, Jansen, Tromp, Croes, Sambo, Martha, Winklaar, Hooi, Lourens, Maria, Janga, Henriquez, Cicilia, Cijntje, Daal, Alberto, Francisca, Leito, De Windt… Among the names of European origin, we also find here names that can be labeled as African: Sambo and Janga, lower on the list possibly Coffie, Wanga, Wawoe, Kwidama, Djaoen, Goeloe, Bito, Hato and Mambi.

More than 500 Dutch people with Caribbean roots bear the family name Sambo. Sambo is considered a stereotypical nickname for a boy of color and is listed as such in a dictionary of swear names

28, but the literal original meaning is ‘child of a mulatto and a black man or woman’. Sambo is a common surname in Mozambique and Nigeria, for instance.

The specific Curaçao name Kirindongo, also spread as Quirindongo throughout the United States

29, as a Papiamentu name refers to the Spanish slang word

querindongo for ‘lover’, but it appears to contain the component

-dongo known from several African names

30.

A family name in Papiamentu with special historical significance is the name Kenepa. The noun kenepa designates a fruit tree that has the scientific name melicoccus bijugatus. The family name adopted in the City District by two sisters and a bevy of children presumably refers to the Kenepa plantation. Now there is a museum commemorating the slave uprising that began here in 1795 led by the folk hero Tula.

4.3. Creativity and Allusions

Focusing on Dutch-oriented names, we see some well-known Dutch names, such as Jansen and Tromp, and then some specific variants of Dutch names, such as Croes, Winklaar, Hooi and De Windt. Originally, they were the names of settlers. Croes is a very well-known name on the island of Aruba.

Lower on the name list are names similar in creativity to names obtained in Suriname. To name just a few that catch the eye: Windster (‘windstar’), Toppenberg (top ‘summit’, berg ‘mountain’), Scharbaai (schar is unclear in this context, baai ‘bay’), Trouwloon (‘loyal wages’), Vlijt and Vlijtig (‘diligent’), Vrutaal (possibly vernacular for brutaal ‘insolent’), Winterdal (‘winter valley’), Welvaart (‘welfare’, but already familiar in the Netherlands), Van Eer (eer ‘honor’), Goedgedrag (‘good behaviour’), Sparen (‘to save’), Milliard (‘milliard, billion’), Mutueel (‘mutual’), Flaneur (‘flâneur, stroller’), Loopstok (‘walking stick’), Blindeling (‘blindly’), Kleinmoedig (‘small-hearted’), Scherptong (‘sharp tongue’), Kibbelaar (‘quibbler’) and so forth.

Some obtained names allude to the name of a former slave owner. A good example is the name Rooispruit for a child or sprout of a man named Rojer. However, the surname Rooispruit does not exist anymore, while Rojer as a specific Antillean name form is well represented in the Netherlands and is more common than Roijer or Royer, the name form traditionally found in the Netherlands. One such allusive name that did end up in the Netherlands is the family name Borgschot, adopted in 1863 by former slaves of the slave owner and magistrate named Schotborg. Another one is Torbed, an inversion of Debrot. Balmina Elbertina Torbed, born in 1825, belonged personally to Mrs. Suzanna G. Debrot (1812–1863)

31. The family name Torbed was also given by other members of the family Debrot.

Let us imagine how one evening in May elsewhere on the island all of them from the Saint-Michael plantation gathered on the porch of

shon or master Généreux de Lima, who was himself a colored person, to face the fact that they needed a last name. Someone, perhaps De Lima himself, started playing around with the name De Lima and came up with the names Delmina, Madeli, Lidema, Milade, Demila, Medila, Dimela, Ledima, Dameli, Demali, Lademi, Lamedi, Medali, Limade, Lemadi, Dimale, Damile, Daïmle, Madile, Deimla, Leimda, Meïlda, Mialde, Dalide and Delmai en Liamde. These were the names De Lima passed on to the district commissioner

32. Johanna, 36 years old, obtained the family name Demali for herself and her four children. Theirs is one of only two known in the Netherlands nowadays. Someone named Dimale also ended up in the Netherlands. But his or her name seems to be an original West African name

33. So, by mixing up his own name, shon Genereus, as he was known, accidentally created a real African name for one of his freedmen.

You can jest about this, but actually here different names were formed from an existing name pretty much as is formally prescribed for name changes in the Netherlands. These transformations of existing names in 1863 do not indicate kinship but mutual recognition.

4.4. Metronymics and Patronymics

We recognize many adopted names in the current Dutch name stock. But apparently many slave names known from the slave registers or borderels also entered on occasion directly into civil status records. We can see this simply because the family names that go back to first names are in the majority of the Dutch Caribbean family names. The most distinctive family name category of the Netherlands Antilles concerns the metronymics: surnames derived from female first names. The most frequent Antillean name is one of them: Martina. But patronymics also stand out. Martis, number two above, is therefore the most frequent Antillean ‘patronymic’ in the Netherlands.

An explanation is the strong relation to the Roman Catholic Church. Most slave names were in fact baptismal names, and they proved stronger than assigned surnames when it came to the acquisition of personal data at the Civil Registry.

In the above list of the most common Antillean family names in the Netherlands after Martina, the following metronymics can be distinguished: Martha, Maria, Cicilia, Cijntje and Francisca. Also common in this category are the names Isenia, Paulina, Bernardina, Marchena, Mercera, Mathilda, Mercelina, Angela, Juliana, Felicia, Pieternella, Cecilia, Manuela, Molina, Leonora, Antonia, Rosa, Paula, Rosalia, Poulina, Bernabela, Carolina, Elizabeth, Isidora, Louisa, etcetera.

Most are Spanish names, but there are also some names that reflect the Dutch presence. In the old-fashioned name form Cijntje, also written as Cyntje, we should read the formerly popular given name Sientje, a diminuvated short form of Christian names ending on -cina/-sina, such as Francina, Gesina, Josina and Klasina. Other family names from specific Dutch girls’ names include Pieternella, Elizabeth, Gijsbertha, Geertruida, Cornelia, Dorothea, Theodora, Celestijn, Seintje (variant of Cijntje), Bregita, Noor, Gustina, Adriana, Roosje, Daantje, Margaretha, Jennie, Jakoba, Wieske, Roos, Lambertina, Balo(o)tje and Ansjeliena, some of which are certainly also international and the last one is just a Dutch spelling form for the Spanish name Angelina.

Such a list can also be made of the common family names that are based on boys’ names: Lourens, Henriquez, Alberto, Willems, Geerman, Frans, Pieter, Thomas, Martinus, Martijn, Albertus, Pietersz, Girigorie, Anthony, Thielman, Williams, Nicolaas, Ricardo, Adamus, Pieters, Jones, Jacobs, Rodriguez, Ignacio, Hansen, Chirino, Peterson, Engelhardt, Alexander, Hernandez, Lopez, Janzen, Manuel, Simon, Simmons, Christiaan, Evertsz, Gomez, Balentien, Job, James, Martes, Minguel, Lucas, Jacobus, Everts, Dirksz, Joseph, Philips, Martien…

Most of these names are Spanish, Dutch and English, some transformed by the Papiamentu vernacular. Among them we find a number of names of old Dutch families (Willems, Pietersz, Jacobs, Janzen, Evertsz, Dirksz) and some common Spanish and English patronymics. But it is noteworthy that many of these family names, and in fact all of the metronymics, are just identical to first names. Except for those archaic Dutch patronymics, these family names lack the additions of genitive inflections or worn forms of zoon ‘son’ and dochter ‘daughter’ that are characteristic for traditional patronymics and metronymics. Enslaved people were known as Xxx, which was their slave name, of Yyy, which was the slave name of their mother. In the slave registers next to the slave names of the enrolees, the names of the mothers are listed. Whether the matrifocal aspect of the African slave community was traditional or not, the subordinate role of the fathers was brought about by authority in the slave registers and borderels anyway.

4.5. The Influence of the Catholic Church

A glance at the borderels evokes the image of a society in which many newborns were carefully assigned fancy names. They often had two baptismal names. For instance, five of the sons of Cathalina Isenia were named Martis Martien, Willem Martis, Theodorus Martis, Juan Martis and Benedictus Martijn; she herself was a daughter of Maria Rosaria.

Since we can assume that many family names entered the Civil Registry from the slave registers or borderels, it is also plausible that often second given names were considered surnames. Hence the high frequency of Martina and Martis as family names as well as regular Dutch forms as Martinus, Martijn and Martien. The popularity of (second) given names deriving from Martinus is probably due to the popularity of the first apostolic vicar Martinus Niewindt (1796–1860).

A factual example of the adoption of a second given name is the surnaming of Maria Victoria, to whom, as well as her two children, the family name Victoria was assigned in the register of freedmen in the City District

34. We also find here an explanation of some Antillean family names that seem to have originated from person designations in the religious sphere. The family names Apostel, Obispo and Confessor were known as second baptismal names in the borderels

35.

Those slave names in the borderels are not given by slave owners. Most of them are Roman Catholic baptismal names. Roman Catholic priests baptized the slaves and their children. The Dutch elite was not Roman Catholic.

And what about those remarkable names, including several names after historical and literary characters, with which a number of children have been honored? There were two dozen Napoleons, including a Louis Napoleon and a Napoleon Emperator as a slave owner! Several Wellingtons, more than a dozen Washingtons, three Garibaldi’s born in 1860, several Cesars and a Julius Cezar, a Julius Maximilianus, a Hannibal, a Horatius, a few Olympias, a Lycurgus, an Othello, a Torquato Tasso, a Lucretia Borgia and several other Borgias, a Menzikoff

36, a few Miltons and Melvilles.

Whoever came up with these names, it cannot be denied that he or she had no regard for history and literature and had a rich imagination. One consequence of this, at least, is that currently in the Netherlands, descendants are walking around with the names Washington, Borgia and Milton, which are in fact unremarkable family names worldwide. The other names mentioned did not reach the Netherlands as a family name.

Although the common slave name Napoleon was assigned also as a family name, it does not seem to have survived either. However, from Suriname, the family names Bonapart and Bonaparte remain. It is understandable that nowadays someone would be uncomfortable with this name. It must be like running with the name of a dubious sports hero from long ago on your back. Imperator is an Antillean family name in the Netherlands. Finally, the family names Corsica and Austerlitz can also be mentioned as Surinamese-Antillean names from the Napoleonic theme. The adopted family name Solferino, recalling a victory of Napoleon III, has not proved viable.

5. What Is at Play Regarding the Intended Amendment and Some Critical Comments

5.1. Preliminary Investigation for the Purpose of the Law Amendment

Afro-Surinamese and Afro-Antillean immigrants will be allowed to formally change their names in the Netherlands. They do not have to pay the usual fees. This is the politically accomplished and socially encouraged proposal to be legally developed. The Research and Documentation Centre of the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security commissioned the Verwey-Jonker Instituut, which conducts research into the social issues of today and tomorrow, to conduct an exploratory study, for which the Verwey-Jonker Instituut organized several expert meetings with the theme ‘name change in connection with the Dutch slavery past’.

There has not been a discussion about possible consequences. The righteousness implied by the revision of the law is sufficient. Even the actual demand for name change has not been checked.

In fact, the Verwey-Jonker Instituut was merely asked to ascertain whether there were name lists of slaves on the basis of which it could be shown that any application indeed concerned a descendant of an enslaved person. It seems that preliminary investigation had been initiated without realizing that slaves had no surnames at all. Manumission records and Emancipation Registers then had to connect the names of descendants to slavery.

The final report concludes that there are many useful sources, especially as far as Suriname is concerned, but there are also gaps, so that the undesirable situation can arise where a person assumes that his or her name is one associated with slavery but cannot prove it. It is therefore recommended that documentary evidence be waived when processing applications for name change by descendants of slaves. The perceived individual need should be leading, possibly combined with domicile of one of the ancestors

37.

The Cabinet response to ‘Chains of the Past’, the report of findings of the Advisory Committee of the Slavery Past Dialogue Group, dated 19 December 2022 and signed by the prime minister, includes a paragraph on surnames that incorporates this recommendation

38 (

Figure 5). No heavy burden of proof needed is the premise. The Verwey-Jonker Instituut report also notes that experts advocate a generous approach toward newly created names. They realize that the current practice of name changes leaves little room for a radically different, new surname. A new family name according to the rules that it is formed by transposing a few letters of the original name or adding a prefix or suffix, or replaced by a name that does not yet exist in the Netherlands and sounds Dutch, then still remains a burden for the person in question. Minister Weerwind of Legal Protection instructed his legal officials tasked with drafting the new legislation to take these empathetic suggestions to heart

39.

5.2. What Is the Situation Actually with Regard to the Dutch East Indies?

So far, we have only discussed the slave name situation in the former West Indies colonies. However, the scrupulous staff of the Verwey-Jonker Instituut also convened a meeting regarding this issue in the Dutch East Indies, present-day Indonesia. Actual slavery as in the West Indies has been also evident in the East Indies but in the ages before the abolition of the trade in enslaved people in 1807. The more complex Dutch East Indies history reveals mostly imposed docility of the indigenous population toward the colonists, in which the hierarchy within the Indonesian principalities also comes into play. There are no naming lists that can prove a relationship between slavery and naming. Although the inference of the benevolent policy would be that leniency should also be offered to persons of Asian origin who would like to change their European family names, this cannot but lead to the uncomfortable insight that the Netherlands, after the transfer of sovereignty to Indonesia in 1949, only accepted

repatrianten (‘returnees’). Most of them had Dutch or European names, but they never had been in Europe before. The point is that the returnees needed to be assigned the Netherlands nationality. The archive of approximately 150,000 applications for Dutch passports was recently made available online by the CBG Center for Family History

40.

5.3. New Colonial Names Compared to Common Dutch Names

Although the assigned family names of the freed slaves in Suriname and the Antilles have been attributed the abjectness of slave names, the names in question are really the result of liberation and inclusion in the Civil Registry as citizens. They are also assumed to be derogatory names that differ from common Dutch names. It is refuted that the authorities in charge were acting in good faith. Those who were surnamed had no free choice.

What is overlooked is that not only were family names obtained but also individual first names, which often differed from their slave names. This indicates that at least their choice of Christian names was respected.

From an onomastic point of view, those eligible for name change are no worse off with their names than the rest of the Dutch. We may frown at names like Bakboord (‘larboard’), Bijlhout (‘axwood’), Boekstaaf (‘book rod, bookmark’), Muntslag (‘coinage’), Zeefuik (sea trap), Windzak (‘windsack’), Bergwijn (‘mountain wine’), Graanoogst (‘grain harvest’) and Purperhart (purple heart), but they are no more peculiar than traditional Dutch names such as Baksteen (‘brick’), Botbijl (however, not to be explained as ‘blunt axe’ but as a broadly shaped axe), Boekweit (‘buckwheat’), Hamerslag (‘hammerblow’), Zeevat (‘sea barrel’, but probably a folk-etymological reinterpretation of a foreign name), Hoppezak (‘hopsack’), Aardewijn (‘earth wine’, but probably from Hardewijn, from a Germanic personal name hard ‘strong’ and win ‘friend’), Wijnoogst (‘wine harvest’) and Groenhart (‘green heart’), a name also been chosen in Suriname but already existing as a Dutch family name. Also, the family name Bijlhout had long been known in the Netherlands as a less common variant of Bijlholt.

Against the names Crisis and Hongerbron mentioned in paragraph 3.5, we can place the primal Dutch names Onrust (‘unrest, turmoil, uprising’) and Hongerkamp. The latter surname has been derived from a field name denoting poor soil quality, and Onrust goes back to a house name.

Playing with names by alternating syllables is a procedure that has been used before. The family name Omtzigt, similar in meaning to the Surinamese name Omzigtig (‘cautious’, from the verb

omzien ‘look around’), originated in a Dutch village with several farm names containing the word

-zicht ‘view’, including Cromzigt (

crom, krom ‘curved, bent’), which also became a family name, and refers to the view over the river Kromme Mijdrecht

41.

5.4. Those Who Have Expressed a Desire to Change Their Name

Media interviews indicate that there is interest in name change primarily among descendants who realize that the spiritual and cultural renaissance they experience as people of African descent does not match their inherited family name. Thus, members of the Ojise Foundation unofficially adopted an African name. Founder Delano Hankers changed his names to Kofi Ogun. He was born on a Friday, hence Kofi as his new first name. He says Ogun means ‘guide’ and he wants to guide his people. Ogun is a common Nigerian surname, by the way. According to the Dictionary of American Family Names, Ogún is the traditional god of iron and war in the Yoruba religious culture

42. Delano Hankers’ alias Kofi Ogun has not tried to change his name officially yet because he is against having to obtain a document in which a psychological expert declares that he is mentally better off with a new name, as is now (still) a requirement for him in the proceedings

43.

Someone else who has come forward in the press with his name change did submit a psychiatric testimony to the Justice Department for this purpose. Jeffrey Buckle, from Ghana, was troubled by his last name since his aunt had told him that his forefather had had this name forced upon him after living in American slavery. Buckle is a common English name, though, and it is also common in Ghana. Jeffrey was allowed to exchange his father’s last name for his father’s middle name, Quarsie

44. With an opinion piece of his own in a daily newspaper, Jeffrey recently advocated that everyone should have their slave names changed

45.

Quarsie is unique in the Netherlands with this name form, but his new family name is, in fact, a variant of Quarshie and Quashie, Anglicized forms of the personal name Kwasi, denoting a boy born on Sunday, which forms as well as Kwasi and Kwasie, which are nowadays also part of the Dutch names treasure. Kwasi and Kwasie are rare examples of African family names from Suriname.

5.5. Dubious Traditional Dutch Names

What has not come up in the discussion is to what extent slavery and the taboos associated with it are reflected in Dutch naming traditionally. In terms of nicknames, color has always been a favorite reference. Although we must take in account that it may have been the color of one’s nose or clothes, we may assume that the family names De Rooij (The Red), De Wit (The White), De Bruin (The Brown), De Grijs (The Gray) and De Zwart (The Black) mostly refer to the hair color of the ancestors who were assigned these names, to which is to be added the expression of shades of hair and skin in names such as Blank (White, without color), Bleecke (Pale), De Blonde (The Blond), De Ligt (The Light one) and Donker (Dark).

These names are very common family names, and each has numerous variants, with or without an article. In the 12th century, count Dirk VI of Holland had a brother named Floris de Zwarte, and this Black Floris put himself at the head of the Frisians to take up the fight against his brother. Because of his surname, we assume that his hair was black. Did his skin also have a blackish complexion? Not necessarily.

However, a certain

Louwerens de Swart (Laurence the Black) was kidnapped from Madagascar in 1595 and brought aboard as a slave. At the time of his baptism, he had survived many hardships and established an admirable record of service. It is unknown if he has offspring, but it should not be ruled out that he passed on his name to later generations

46.

The family name De Moor is another name established early in the Low Countries

47. The name refers to the folk name the Moors, a people in northwest Africa called Mauri by the Greeks, from

mauros ‘black’. The motive for giving the surname could be that someone who was so named was a Moor, resembled a Moor, was a traveler to the Moorland or lived in a house known, for example, as The Smoking Moor with the image of a smoking Moor on a signboard. The noun

moor denotes a black person.

Every year in December, Sinterklaas is celebrated on a grand scale in the Netherlands. Our Saint Nicholas arrives by steamboat from Spain. With him travels a bunch of Zwarte Pieten (Black Peters). Actually, Zwarte Piet was as black as a Moor, but he is not anymore. Wherever he appears in front of the children now, he is just a white servant with sooty patches, caused by climbing through chimneys, or he is painted with all the colors of the rainbow. Only in villages where Christian conservatism reigns supreme is he as black as ever. The association of Black Pete with slavery has become taboo, as has the use of the word zwarte ‘black’ for a descendant of an enslaved person.

Also derogatory is the use of words such as neger ‘negro’ and nikker ‘nigger’. You may be surprised, but we also have family names like Neger, Hottentot, Kroeskop, Balneger and Balnikker in the Netherlands. In explanation of the N-name, a homonymous way out is offered. Neger is also a German name and is explained as such from the occupational name Neher or Näher for someone who sews fabrics, a sticher or tailor. But just as the noun neger originated from French nègre, from Latin niger ‘black’, in the Netherlands, the family name Neger may also have originated from the common French surname Negre, and then it is really about a Black person.

Someone named Hottentot was banned from Facebook for using his real name

48. Possibly, there really is a connection to South Africa. Someone named Jan Hottentot of Amsterdam born at the Cape of Good Hope was listed with his son Abraham Hottentot in 1779

49.

Kroeskop ‘frizzyhead’, associated with the hair growth of someone from Africa, may simply be a nickname for someone with frizzy hair. But Kroeskop will be felt by everyone as a pejorative name.

While it may be reassuring that Balneger and Balnikker are adaptations of a Swiss topographic name, probably referring to a location called Balmegg

50, this does not take away from the fact that in both derivations those two taboo words have emerged.

Since the Black African population has been abused for centuries for the sake of slavery, the word negro has become synonymous with slave. Dehumanizing stereotyping then requires distancing oneself from the terms in question.

What about the above family names? Because of the connotations, name bearers who want to get rid of their names will obtain permission to change their names. But will it pay to try to get out from under the dues?

6. Plea for a Wholesale Overhaul of the Name Law

6.1. Problems with Amending the Name Law in Favor of a Single Population Group

There is no easy task for those who must legally shape the generous accommodation of those who wish to change their name if it is the name of an ancestor who lived in slavery. By casually advocating leniency for the type of names selected, the report already realized that it is not enough for those involved to provide that they may change their names for free. If someone is willing to change a family name that qualifies as a slave name into a new Dutchy name, the creation of the new name is actually as patronizingly guided by government representatives as it was with the name adoption in 1863. The new name will still be linked to the slavery past.

The current practice of name changes leaves little room for a radically different, new family name. The rules for determining a new name to be chosen should also be updated. But how can this be legally met if the restrictions apply to all name changes? Should the stability of the Name Act be further compromised by giving a certain population the right to a free choice of name and continuing to restrict other people from doing so?

Moreover, the well-intentioned approach of asking for hardly any burden of proof actually leads to objectionable ethnic profiling. After all, anyone with African blood who does not have an African name qualifies.

6.2. The Population of Suriname and the Antilles Itself Has Not Been Taken into Account

Apparently, it is assumed that initially only the select few who have already expressed an interest in changing their family name will take advantage of the new arrangement and that also in the future the opportunity will be seized only on the basis of individual decisions taken after ample consideration. One might be right about that. The institute’s report shows that they are well aware that not everyone in their own circle will be happy with a family member’s name change. Although aware of this, the view remains that the opportunity to change one’s name, for the sake of the individual’s wishes, should be provided for in name law.

So that ignores the fact that all Afro-Surinamese and Afro-Antilleans, not only here in the Netherlands but also overseas, will face this change in the law, which not everyone will be convinced is in their favor. Free name change for our family members in the Netherlands? Is this not actually another patronizing imposition? Is independent Suriname supposed to follow? The accommodating policy could be seen as intimidating.

Suriname’s population is made up primarily of the Creole descendants of African enslaved people and their low-paid successors who were lured to Suriname for the benefit of the economic interests of Western European investors. The Hindostans from India were initially only numbers. They were registered on arrival under ship, year and a number in Paramaribo, such as LR73 no. 392. The Javanese created compound names with recurring components in various names: Kartopawiro, Pawiroredjo, Redjopawiro, Kartoredjo, Kromopawiro, Pawirodikromo and so on. In the Netherlands, there are 150 names with the Surinamese-Javanese component kromo ‘the simple people’, 92 with redjo ‘happiness, wealth’ and 75 with pawiro ‘warrior’. The Chinese were registered with their entire string of names as one family name (they consist of the xing ‘family name’ plus the ming ‘personal name’).

The population in the former West Indian colonies is a veritable hodgepodge from everywhere.

The Verwey-Jonker Institute also involved experts from the Caribbean part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in their meetings. They reported that the need for the possibility of name change in the communities of descendants of enslaved people is not great and certainly not in the Antilles itself. One even looks a little suspicious of the name change discussion. A quote by one of the experts from the report is as follows: “As if we should distance ourselves from a name that refers to the slavery past? That seems a bit odd to me. Do they want to polish something away on the seventh island (i.e., the Netherlands)?”

The very indulgent inclination shows indifference. One has not really bothered to look into the acquisition of the names, and one assumes unquestioningly that they are derogatory slave names. The general view in the Netherlands that it is good that slavery-infested names could be changed for free means that all descendants have to be made aware that they bear controversial names. Their name is no longer a piece of evidence that made their ancestors full citizens, but it has become a stigmatizing name, one that merely associates them with slavery.

6.3. More Imperfections That Were Not Considered

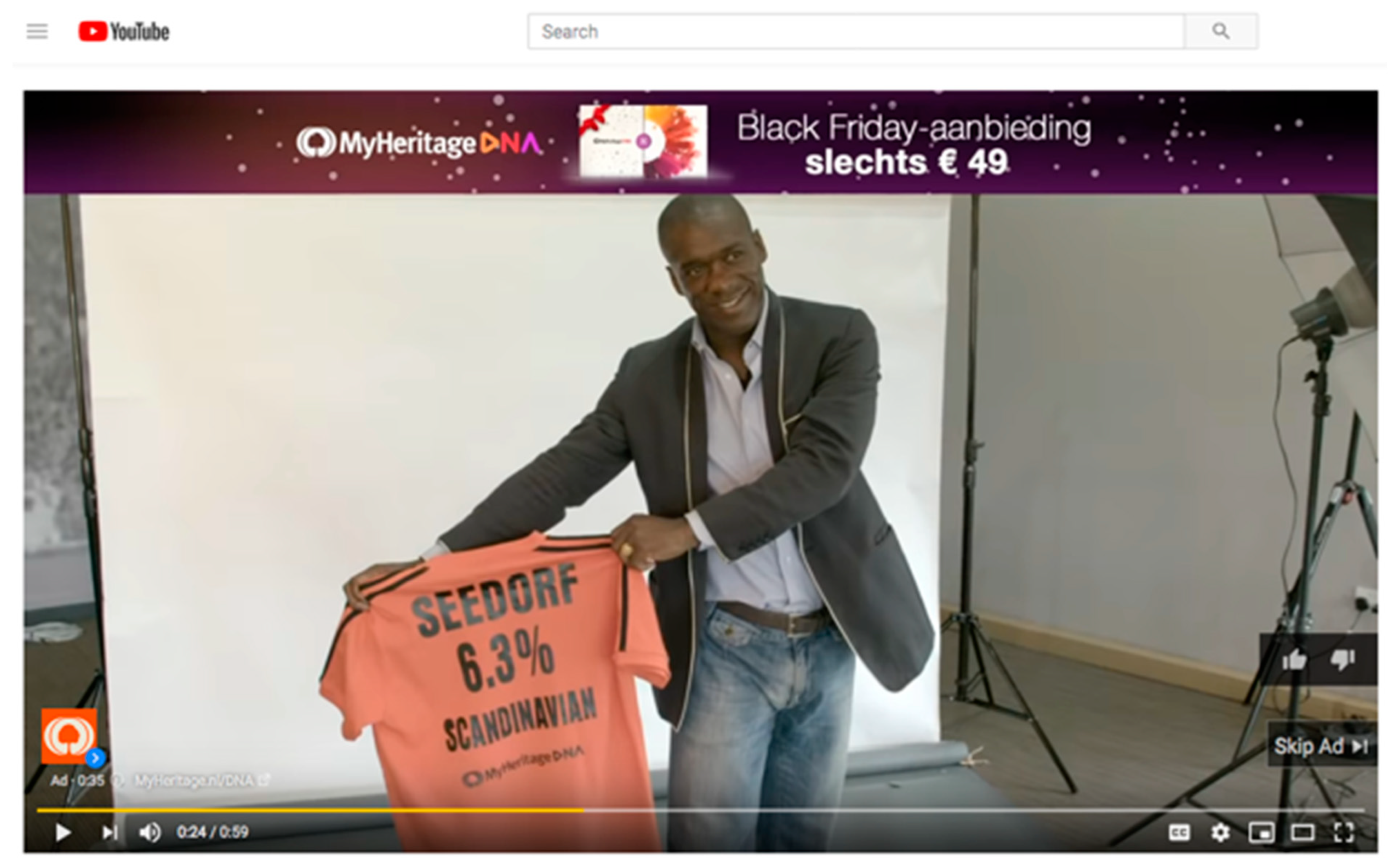

Also, by reverting to the names of the past, the Dutch government is pandering to the realization of a black and white image, while

black comes in all colors nowadays

51. Clarence Seedorf advertised for MyHeritage that DNA testing revealed that he is 6.3% Scandinavian (

Figure 6).

The family name is an essential part of one’s family history, but it is only one name out of four in three generations and one out of eleven if one’s great-grandparents’ generation is included. A name is not one history. Who today is named Rijkaard, Winter, Seedorf, Kluivert, Bogarde or Davids, just to name a few Surinamese-Dutch soccer players who contributed to Ajax’s fame several decades ago?

Dwight van van de Vijver bears his manumission name as a

geuzennaam, which is a Dutch term referring to the Geuzen, a rebellious group of freebooters during the Eighty Years’ War, who bore their mocking nickname with pride. Relationship between owners and former slaves expressed in derivation of names could be complicated

52, but if DNA testing were to reveal that he is actually related to the Van de Vijver family, then under the current name law he would simply not be allowed to drop the ridiculous and embarrassing first

van for the Kafkaesque reason that Van de Vijver is an already existing Dutch name.

In family circles, the unpronounceable name Tdlohreg may be pronounced as Gerholdt. A request to change Tdlohreg to the original form Gerholdt would probably be accepted, since the German surname Gerholdt is not known in the Netherlands today. But this correction drives the reversed Gerholdts unmistakably into the arms of their former possessors. One has to make all sorts of considerations. Another branch of the family may prefer to create a very different name. Finally, perhaps no one will change this name, no matter how curious the existing name. It is simply theirs.

Those with reversed names with East Indian roots, such as the Rhemrev and Kijdsmeir families, however, need not discuss the option of name change because their names are the fruit of a relationship between a settler and an indigenous servant and not with an enslaved servant.

Older fellow countrymen may chuckle at the family name Geertruida, because for them, Geertruida is particularly an old-fashioned feminine first name, a Dutch form of the German personal name Gertrud. But probably his family name will not bother Lutsharel Geertruida from Curaçao, the tough defender of national champions Feyenoord, even though his family name is one of dozens of Antillean metronymics that attest to a slave past. In the Caribbean islands, those metronymics, as well as many patronymics, did indeed originate from slave names. Those slave names were actually (Catholic) baptismal names and not names given by (Protestant) slave owners. They survived the half-hearted attempt to provide the freedmen with a ‘real’ family name of their own in 1863. Descendants now face the dilemma that by changing such a name they may be brushing away bondage, as well as an imposed Catholic religion, but they are also renouncing the name of their dear foremother.