Abstract

Rose Selwyn (1824–1905) was a first wave Australian feminist and public speaker. The poetry, art, and scraps of writing Rose left in her archive allow the reader to piece together an intellectual history, a genealogy of the making of self. Rose attained her way of being through several contemporary influences—the mysticism of Tractarianism, a concern with death and its meanings, an interest in the literary edges of the world, a concern with the suffering body, and a passion for women and a woman-centred world. From these tangled contemporary concerns, she made a feminism for all non-Aboriginal women apparent in her speeches. Her role as a colonising woman in a violent landscape created a complex relationship with Aboriginal people where she may be seen to be criticising her elite landholding (squatter) peers and introducing concepts such as an Aboriginal parliament.

1. Introduction

Genealogies of ways of being in the world give an insight into how individuals assimilate currents of thought and how they make themselves as persons. In intellectual life, poetry, novels, or theological texts combine and contribute to self-positioning. This paper concerns the making of a female mind in late nineteenth-century Australia in a woman who espoused feminist ideals of her own. There need not be logic nor reason in the making of self, nor need there be an understanding of this process by contemporaries but the historian pieces together the aesthetics of intellectual selection in order to understand how ideas were lived in a particular period. In exploring the making of Rose Selwyn, we see the making of one kind of late nineteenth-century feminist through currents in poetry, religious mysticism, and notions of the suffering body. Any conception of how women assimilated or altered religious and philosophical positions for their own purposes, even unconsciously, haltingly, or in a contradictory manner, illuminates what it was to be female in the late nineteenth century as well as the emergence of one strand of first wave feminism.

The records surviving from Rose Selwyn’s life, held in the Mitchell library in Sydney, are not a straightforward documentation of her feelings and ideas and we must deduce these from texts Rose copied out or created in the manner of a scrapbook. Her unpublished memoirs, written around 1904, follow the same pattern—scraps of recollections from childhood, marriage, and poetry, rather than a full narrative account. Scrapbooks have been described as part of the making of self in nineteenth-century women; the piecing together of aesthetically selected texts both represent and create the woman so engaged (Pettitt 2016, p. 21; Mecklenburg-Faenger 2009, p. 41; 2012; Arnold 2003, p. 171; Daly Goggin 2017, p. 10). Such “elliptical” research from scraps has been explored by Dever et al. (2009). One approach they suggest is Page Du Bois’—to use fragments to create “a dream of wholeness” (Dever et al. 2009, p. 101). In this paper, such a dream of wholeness concentrates on the belief system of a woman who collected poetry and copied texts, discussed books, created watercolours, and produced documents in the public sphere. This paper thus emerges from the close analysis of letters written to and by Rose, from a scrapbook that lasted her whole lifetime containing her own, her sister Amelia’s, and others’ poetry and texts, including a short story Corporella, a series of watercolours produced mainly around Grafton on the Clarence River, and her public papers—records of speeches and addresses she made from the 1880s. This dream of wholeness concerns the connections a historian makes between partial documents. In doing so, this paper does not prioritise the ‘public’ or see it as a binary to the ‘private’ (Klein 1995, p. 97) but rather sees both as constructed by Rose in her life. Julie McIntyre and Jude Conway show that Rose was a significant figure in the formation of the Women’s Suffrage League and the obtaining of the vote for women in New South Wales in 1902 (Conway 2017, p. 1; McIntyre and Conway 2017, p. 182). This paper concentrates on how Rose Selwyn evolved and comprehended the world, how she perceived what it was to be female and her own idea of a public.

Extensive work on Australian feminism has shown the various pathways by which late nineteenth-century women began to espouse perspectives on the rights of women. For example, the novelist Ada Cambridge was influenced by John Stuart Mill and transcendentalist ideas (Bradstock and Wakeling 1991, p. 120; Tate 1991, p. 10). Susan Magarey has shown how Catherine Helen Spence rejected the Calvinism of her upbringing in favour of the Unitarian church, in which she became a preacher (Magarey 2010, p. 66). Maybanke Wolstonhome was divorced and ran a school in Dulwich Hill Sydney where she adopted progressive ideas about sexual autonomy in marriage. She published The Woman’s Voice in 1894–1895 (Sheridan 1993, p. 114). Louisa Lawson was from a rural labouring background and was educated in a National School where she excelled. She married in the Wesleyan chapel at Mudgee but gravitated to the local spiritualist group. Those connections allowed her to join the Progressive Spiritualist Lyceum in Sydney, leading to her establishing the newspaper Dawn for the New Woman (Mathews 1998, p. 10) Helen Jones has shown how women of the Social Purity Society in South Australia met informally after the society’s disbandment, and “began to recognize that a propelling motor in the downgrade of womanhood was that they had no recognition as citizens” and organized for suffrage (Jones 1986, p. 85). Such women, including Rose Selwyn’s niece, Rose Scott (Allen 1994; McIntyre and Conway 2017), were voices in late nineteenth-century Australia and were contemporaries of Rose. However, much of this work is biographical and concentrates on accessing a public sphere rather than a detailed discussion of influences and ideas. Such a biographical focus and a focus on action rather than thought may have been partly due to the kind of records remaining. Lucy Gray did not give her biographer, Meg Vivers (Vivers 2013, pp. 36–38), any close idea of the basis of her own Evangelical religious belief. Studies of groups of women provide more information on intellectual influence. Susan Magarey examined first wave feminism in Australia from 1880–1930 and she sees the discourses around health as generating the subject positions of this mobilisation of women (Magarey 2001, p. 3). Rose’s concern with the body comes from a different direction. Magarey considers the influence of popular magazines on feminism, the library of Edith Cowan, and the Karrakatta Club, and her project is closest to this research on Rose (Magarey 2001, p. 40). Jill Roe in Beyond Belief discusses the influence of theosophical ideas on women in the early twentieth century and the involvement of women as delegates to Theosophical conventions as the organization became feminized (Roe 1986, p. 184). This occurred after Rose’s death but, in her study of English theosophy, Joy Dixon writes of the links between the Tractarian beliefs Rose engaged with and Theosophy. Some nineteenth-century feminists from this tradition saw women as “the morally and spiritually superior sex” (Dixon 2001, p. 7). This was certainly Rose Selwyn’s position, but it was obtained by a complex route and that route is the subject of this paper. This paper emerges from an interest in women’s construction of self.

Rose Selwyn was the youngest daughter of Ann and the Reverend George Keylock Rusden of St Peter’s Church, East Maitland. The family had arrived in Australia in 1834 when Rose was 10. Rose married Arthur Selwyn in 1853. Arthur had originally wanted to be a squatter; these were men who took up huge tracts of land, initially illegally, and attained considerable wealth (Roberts 1964, p. 37). Arthur did not have the capital to continue as a squatter, so he became a reverend and studied for his ordination in Brisbane. He was subsequently employed at Grafton from 1853 to 1867 and then at Newcastle where he later became Dean (Selwyn 1899, p. 1). Rose’s last piece of writing may be dated to late 1904 and she died in 1905. Rose is not representative of the ‘middle classes’. Rather, her family link to squatters through her brothers (two were also parliamentarians) and her brothers-in-law meant she would see herself as quite different to the shopkeepers, publicans, and merchants who made up the colonial middle class. This paper cannot be seen as a history of middle-class thinking.

Rose Selwyn exhibited an interest in the edges of the world and in mysticism and anxiety about death. She also engaged with the embodiment and the suffering body of Christ. It was the suffering body that most influenced her version of feminism. Rather than seeing the world from a philanthropic position where woman helped and guided, Rose identified with the suffering body of woman as ‘we women’ and her speeches and public documents sought to alter the public world so that women’s special nature would have influence. Her apprehension of the world from this position of suffering excluded Aboriginal people and Rose exhibited the humour of her squatter contemporaries. However, as a kind of subtextual, hidden reference, Rose could also be seen to challenge squatter dominance and to invoke the idea of an Aboriginal parliament. Her emphasis on ‘civilising’ Aboriginal people, however, fits the pattern of orientalist feminism in which European culture was the ideal.

2. Mysticism and Interiority: A Background

Walter Houghton describes late nineteenth-century ideas and theories as existing in a contradictory jumble and the popular response of Victorians was to emphasise interiority and feelings rather than intellect. The age is one of “uncertainty,” he wrote in his study of the major intellects of the period (Houghton 1957, p. 16). Michael Wheeler shows that, in religious thought, the writings of Cardinal Newman, Tractarian turned Catholic, with his spirituality and mysticism, far outsold any Anglican literature (Wheeler 2006, p. 246). Kate Flint has discussed visuality, the interest in symbols and the related interest in the “unseen” and the unconscious (Flint 2000, p. 10). Jan Melissa Schramm discusses the “individual suffering body” as the prism through which anxieties were refracted and the emphasis on sacramental power and sacred aesthetics in theatrical and public life (Schramm 2019, p. 130). Elements of this climate of thinking can be found throughout Rose Selwyn’s papers.

In May 1863, Amelia Gillman sent her sister Rose Selwyn a memorial of a visit to a graveyard on the Isle of Wight. Three ivy leaves were carefully sewn on a page that also described an inscription on the grave of the Reverend William Adams, author of the enormously popular The Shadow of the Cross. Amelia copied William Henry Davenport Adams’ description of the grave (Adams 1863, p. 1). The old Church yard was surrounded by trees “within hearing of the murmurous waves”. The tomb was “coffin-shaped with a cross of iron placed over it horizontally, so as to cast a continuous shadow–an allusion to his book”. The ivy had been gathered in the graveyard. The page represents a complicated set of influences. Ivy symbolised immortality and three sewn in a triangular form represent the Trinity. Ivy, however, because of its link to the God Dionysus, also related to sexual desire and fidelity in that desire (Cobham Brewer 1858, p. 100). It carries both connotations, so that devotion is tinged with sexuality. It is possible to grasp in that combination of emotions some of the sensibility of the late nineteenth century. Adams wrote his works while he was dying of consumption and his last book was a representation of insanity. He was, according to the Dictionary of National Biography, enormously popular (Dictionary of National Biography Volume 1, p. 107) Amelia’s page, like many of the references in Rose Selwyn’s papers, plays with the edges of the world, with death, opium, and insanity.

3. Rose and Interiority

Rose Selwyn had spent her early years in Surrey where her father, the Reverend George Keylock Rusden, educated boys in Sanskrit and classics as part of their training for the colonial civil service at his school, Leith Hill. The family was educated separately but to the same standard (ML A 1616). Her mother, formerly Anne Townsend of a gentry background, was part of a circle of women in England whose interests included science and theology. These women corresponded with Anne and her daughters after the family arrived in Australia (Byrne 2022, p. 46). Anne was influenced by ideas of reason in her theological perspectives, and she encouraged her daughters’ critical thinking and reading. Her youngest daughter, Rose, however, moved in a different, more mystical, direction in her own thinking. There cannot be a precise account of Rose’s development because much of the material is undated, yet her copying and writing of poetry continued throughout her life. Her 1880s short story, Corporella, was didactic, possibly written for the Girls’ Friendly Society. It is headed as if it were meant to be published but no published version survives. Her speeches date from that time until very close to her death in 1905.

Rose was engaged to Arthur Selwyn in 1851. He wrote to her in August 1851, “As far as you say you are perhaps a little much inclined to -what shall I say?–mysteriousness or to be led by your imagination in matters of religious duty” (Selwyn 1899, p. 80). Rose Selwyn’s scrapbook, kept throughout her life, and references to books in letters, indicate that her interest in mysteriousness did not decline following her marriage to Arthur Selwyn who was “rather the reverse” (Selwyn 1899, p. 80). In his early letters to Rose, Arthur wrote of her superiority in comprehending classics and theology (Selwyn 1899, p. 35). In Rose’s short story, Corporella, the Duchessa was “decidedly less intellectual than her husband”. It continued, “surely it is better so; though in this contradictory world in which we find ourselves there have [sic]been exceptions to this rule!” Wives of ministers and squatters spent a great deal of their lives away from their husbands and this allowed them space for intellectual discussion among themselves. Both George Keylock Rusden, Rose’s father, and Arthur Selwyn travelled extensively for their ministry. Such independence may account for the Hunter River female interest in Tractarianism located by David Hilliard (Hilliard 1993, p. 10). It was a branch of Anglicanism that encouraged intellectualism and discussion among women. This formed part of the English tradition. Women of the eighteenth century, such as Rose’s mother, were educated to the same standard as men and this intellectual life was carried on apart from men (Symes 1995).

The idea of the Trinity, shown in Amelia’s memorial to Adams, was a cornerstone of the Tractarian variant of the Anglican faith. Its beliefs favoured ritual, ornament, and communion and adherents saw themselves as deriving from the ancient Anglican church of St Alban and St Brendan, rather than the decisions of Henry VIII (Hilliard 1993, p. 23). This trace of the image of three aligns Amelia and Rose with at least the symbolics of that branch of Anglicanism. Belief, however, need not be subject to any notion of uniformity or discipline, nor need it be logical (Geschiere 1998, p. 212). The Reverend William Adams was applauded because he was able to bring two versions of Anglicanism together in admiration of his allegories, both because of their wild romanticism and their simple messages of faith (Stephen and Lee 1885, p. 107). His most famous text, The Old Man’s Home, involved picturesque descriptions of the Isle of Wight with an account of a man hovering on the border between sanity and insanity. This man was, however, “full of true aspirations to which his keepers were unintelligible” (Adams 1863, p. 10).

Rose’s mother discussed theology and politics with her daughter. Arthur Selwyn wrote in his letter of 12 May 1851 of Ann and Rose reading the sermons of Jeremy Taylor together (Selwyn 1899, p. 76). The sixteenth-century Jeremy Taylor argued, “better learn by love than by enquiry … if he will pass through the mystery with greatest devotion and purest simplicity … this man shall understand more by his experience than the greatest clerks” (Taylor 1990, p. 4). Simplicity, not further inquiry, was very much Ann Rusden’s approach to religion (Byrne 2022, p. 49). Rose would perhaps be more interested in ‘passing through the mystery.’ In 1851, Arthur Selwyn was very worried that his future wife and her mother were reading Manning’s Sermons. The Tractarian, Henry Manning, in beautiful and rich descriptions of Heaven wrote of holiness in everyday life.

The idea of living in Heaven, yet on earth, through such a sensibility appealed to Rose and her mother. Arthur, however, was shaken by this interest and his criticisms of Manning intensified until he wrote to Rose on 17 August 1851.There may be living and habitual conversation in Heaven, under the aspect of the most simple ordinary life. For what does it depend but on these two things, on faith which keeps alive the consciousness–or if I may say, the vision of the city of God,-and on the obedience of our heart to the laws of love? And what are faith and obedience but realities of the Spirit, which all who desire may attain?(Manning 1845, Sermon X)

He wrote two days later “are you still reading Manning?”, indicating he did not expect Rose to follow his warnings and was happy that she read what she wished. (Selwyn Letters 81). Such selectivity between different traditions has been discussed by Boyd Hilton (Hilton 1988, p. 30).I was afraid that we should some day hear of Archdeacon Manning’s secession, I confess I think it is the only thing men who hold the opinions he does can conscientiously do. I imagine we shall see many more follow in his example. We have not yet seen the end of the Romanists plots and Schemes.(Selwyn 1899, p. 80)

The idea of borderlines interested Rose. On 10 October 1851 (A2268), she sent the Italian text and music of Berloiz’ opera Lelio to her family. Enormously popular in Paris in the early 1830s, Lelio involved terrifying visions beheld by a man under the influence of opium (Bloom 1978, p. 361). Her mother, Ann, received the manuscript with enthusiasm and sent it to Rose’s sister, Saranna, so that she “may enjoy its beauty”. Berloiz sought to “shock, surprise and mingle the ridiculous with the sublime” and Lelio dealt with violent shifts in emotion and “successive waves of passion” mirrored in its audience (Bloom 1978, p. 369). Rose’s link to such texts demonstrates an interest in Romanticism, a privileging of feeling over reason, and a concern with the limits of reality. This incident also demonstrates the openness of the Rusden women to discussion. Ann Rusden, her daughter Amelia in her poems, and Saranna showed more interest in Evangelical ideas. Such perspectives were not divisive. Each member of the family was able to flourish intellectually, and Rose’s theology involved mysticism. The books mentioned in her papers indicate an interest in Tractarian views, the poetry of Anne Adelaide Proctor, Tennyson, Browning, and Coventry Patmore, and specifically those poems that dealt with death, visions, and hallucination.

4. Death and the Body

Rose’s scrapbook shows an interest throughout her life in the borderline between life and death. An explanation may be found in the Victorian woman’s care of the dying body and the expectation that women would do this work (Masur 2015). Women were perhaps closer to death and contemplation of the meaning of death. Rose expressed, in her copying, an interest in the uncertainty of the afterlife linked with a notion of the body and suffering. In 1869, Rose copied Robert Browning’s Epitaph in the Catacombs into her scrapbook. A slave who was burnt by Caesar after fighting “beasts”

at the close, a hand came through

The fire above my head, and drew

My soul to Christ, whom now I see.

Browning’s tone is almost flippant, but, as we only know of the slave’s death because a brother, Sergius, “writes this testimony on the wall/For me I have forgot it all”, the speaking voice slips for the reader, who must contemplate memory and no memory in death. The dead man does not speak directly to us; he has slipped behind a veil at the poem’s end. He is gone and his memories have gone as well. This disconcerting end to the poem is reflected in her other poetry selections. “Recollection” was also written out by Rose. Strongly influenced by the Romantic in its invocation of wild landscapes, the poem, too, is anxious. Would a lifelong love, a kindred spirit, recognize the poet after death?

“Too soon, too soon comes Death to show/We love more deeply than we know!” from Coventry Patmore’s V From Mrs Graham (the only stanza copied of The Victories of Love) deals with the void of death. In death there is an uncertainty of the fate of the soul “But this the God of love lets be/A horrible uncertainty?” Patmore’s poem portrays the physicality of the subject, a woman’s body, and her daily labour. At the end of the poem, she is “gone” and “everywhere her grave”. Poems written by Rose herself and by family members were also concerned with death and the afterlife. A poem copied into the scrapbook “New Year 1860” specifically deals with the uncertainty of death and the physical confinement in the buried coffin. The joyous New Year bells “speak not for you silent dead/Neath the moss grown low, decaying/Each in their lonely narrow bed/Seal’d in, silence, hopeful, holy”. Their “souls o’er paradise may range”. The body waits for the soul, for the day of judgement. There are voices from the grave, lonely souls “trodden down by Satan’s will”. There is no reprieve for these lonely, wailing souls. The poem speaks from this narrow-sealed space requesting, “Guard for me a Christian tomb”. This is an anxious Evangelical-influenced poem, dealing with the darkness of the “Prince of air”. Its claustrophobic atmosphere centres on the body after death, still present, waiting. In its physicality, it bears comparison to the art of Dante Gabriel Rosetti, particularly his painting Sir Lancelot in the Queen’s Chamber (1857) where Lancelot is “hardly able to stand in the cramped space” of the picture (Bullen 2011, p. 80).

The sense of a dying physical body appears in other poetry selected by Rose to copy, and this includes poems she and her family wrote on the death of family members. This was related to the loss of young children by her sister Saranna, but Saranna herself did not move to mysticism in response (Byrne 2022, p. 48). Rose’s aesthetic was an intellectual choice. In 1880, Rose copied William Wilberforce’s poem about the death of his wife in 1841, A Vision. Christ, veiled and unrecognised, comes to the door of the house to ask for the dying woman, “there rose this wife and mother, and went into the night/She followed at his bidding, and was hidden from our sight”. Christ is revealed in the last line “for I saw his hands were pierced”. This poem was found among the papers of William Wilberforce after his death and Rose copied it from Volume 1 of his Life, published in the 1860s. Evangelicals like Wilberforce engaged with pain, and this poem deals with the pain of the author and the physical pain of the “piercing” of Christ’s hands as well as the unrecognised Christ in bodily form.

The body as a focus of interest is also found in Rose’s short story, Corporella, written in 1888. Its main subject was women’s work, but it was also concerned with the care of the body. The Duke and Duchessa wear their servant down and the health of the family is threatened. The Dottore saves them quoting “mens sana in corpore sano” [a sound mind in a sound body], a saying “from the heathens” (Cobham Brewer 1858, p. 352). As the servant, Corporella, revives, so, magically, do her employers. In the conclusion to the story, the Dottore recalls his “English mother” saying: “Christians who believe in the Incarnation, the Resurrection and the Ascent of our Lord will strive to honour and reverence both in themselves and in others that body which he thus consecrated and glorified” and “glorify God in your body and in your spirit which are God’s”. Where is your mother, the Dottore is asked “have you lost her?” He answers, “no I have her still in Paradise, she is the best of mothers, there is no past tense with love”. Rose thus places the mother’s corporeality in heaven; it does not wait for Judgement Day. The human body, in this case the female body, the mother’s, is glorified through its connection with God. The link between women as a bodily part of God would strongly inform Rose’s feminism.

The act of copying Wilberforce’s 1840s poem in the 1880′s and the interest in physicality present in the poems she selected have further import due to the mid-century controversy over the incarnation of Christ and the notion of atonement. Jan Melissa Schramm has shown how this controversy over the sacrifice of Christ for humanity provided an underlying tension reflected in English law, politics, and novels (Schramm 2012, p. 130). The painful death of Christ was the atonement for the sins of men and women. How to atone in purity—without falsity or self-regard—became the concern of novels. How to express the relationship to atonement in the ceremony of communion, emerging from the congregation and a recognition of the body of Christ, or through an acknowledgement of symbolism, became an issue in religious thought (Schramm 2012, p. 41; Janes 2009, p. 10). These tensions emerged from engagement with the real, bloodied, and pierced body of Christ. This had powerful ramifications for all cultural life. Schramm writes of the embodiment novels of the nineteenth century, “realist and sensational fiction frequently called upon the reader to view the broken human body and to draw what inferences, physical or spiritual, she or he could from the state of the remains”. The suffering body was a pervasive image of the period (Schramm 2019, p. 129; Blumberg 2013). Rose’s choice of poems in her scrapbook and her own writing therefore engaged closely with contemporary ideas of the body and Christ. She also represented an uncertainty in combining physical death with a smooth and assured transition to the afterlife—this was the ‘void.’ What sustained her faith was mysticism rather than reason.

5. Rejection of Reason

Among Rose’s papers is a small cardboard note concerning reason.

There is not sufficient evidence that there is not a God

It is therefore immoral to believe it

But Men must Act every day

Actions spring from beliefs upon sufficient evidence

We must not act on those beliefs which we have on insufficient evidence

This being so a wise man will act on such beliefs as taken for granted [leading to] lasting useful results

(Moreover if it is difficult to prove an affirmative and it is impossible to prove a negative)

Now to act on a belief that there is no God has if true no such results,

There is in that case nothing.

No God, no hereafter, no judgement, no rewards.

Reason thus speaks impartially and following reason and acting on its dictates we find in a short time that such action opens up sources of evidence hitherto closed and always closed to me who will not act upon reason’s dictates

If any man wishes to do His Will

“And always closed to me” is a rejection of reason, a kind of stepping out of the argument via John. Clifford’s Ethics of Belief was first published in 1877 and argued that belief must be guided by evidence, and it was wrong to believe with insufficient evidence (Clifford 1877). Clifford was a philosopher and mathematician, and Rose appears interested in mathematics—Corporella begins with discussions of equilateral and isosceles triangles, and she includes some of her father’s maths puzzles in her scrapbook. The passage in Rose’s papers does not follow the arguments responding to Clifford by contemporary thinkers nor does it reflect Arthur’s views, demonstrated by his writing in 1851, “Reason kindles human faith” (Selwyn 1899, p. 36). It reflects a struggle with the idea of reason that Rose’s mother had overcome in her reading of natural theology in the 1850s. Ann Rusden easily found that God was unfathomable but the earth, his work, was open to all kinds of investigation (Byrne 2022, p. 54). Here, in 1876, the author refuses “reason’s dictates” and will discover the doctrine of God by doing his will without concern for reason. Newman similarly made such a refusal “All the emotion and desire are on one side of faith, and all the coldness and death on the side of reason” (Shaw 1990, p. 236). From Rose’s interests, apparent throughout her scrapbook, it was such emotion that informed her way of seeing the world.He shall know of the doctrine (John 7.17) Clifford, Ethics of Belief.

This emphasis on emotion, on feelings rather than reason, appears in the scrapbook created throughout Rose’s life and, in this way, the book describes Rose’s way of being in the world. Mysticism, the uncertainty of death, the suffering body, and the edges of the world informed Rose.

6. Woman—Watercolours

While scrapbooks are one means of constructing the self, art works were generally produced for others. Rose’s artworks were exhibited as fundraising for the church (DL PX 62 Image 41), and they were also sent to her family and to England to friends of the family. In Rose’s watercolours, we find what Rose was expected to reflect on her surrounds—an Evangelical interpretation of the town of Grafton and its hinterland in the period from 1855 to 1867. There are elements of the artworks, however, that express more of Rose’s interests in a woman-centred world.

Rose was married in 1853 after being betrothed for two years. Arthur had to complete his studies with the Reverend Irwin in Brisbane, and he was not ordained until well after he was married, riding all night to Maitland alone on 28 September 1853 (Selwyn 1899, p. 90). The Selwyns had been appointed to the parish of Grafton. Rose created a series of watercolours for her family. These were meant to be accurate portraits of the houses and streets of the town. When the Selwyns lost a tall tree from their garden, Ann Rusden remarked on 11 October 1854 that she could imagine how it was missed because she had seen it in one of the paintings sent. Like the scrapbook, the paintings come from different years of Rose’s life and they are worked upon sketches, sometimes two or three of the same subject with pencilled criticisms on them—“bridle too long redraw” appears on a picture of the Post Office from 1861. It was Maria Cristall, a relative of the artist, Joshua Cristall, who in a letter to Grace Rusden read the artworks in a way that was not photographic. She wrote to Grace Rusden on 5 November 1856 that Rose was,

Writing her version of terra nullius, or empty land, Maria Cristall in fact points to an absence in the sketches that moves us into the unreal. Grafton would have been crowded with Gumbaynggir, Yaegl, and Bunjalung people who have their own histories of the country (see websites in notes). No Aboriginal person appears in Rose’s illustrations. The figures drawn in the watercolours were placed there by Rose for specific reasons and they were drawn in after the sketch was completed. Two drawings of the same scene have initially one woman, then two. There is one smocked convict worker, fixing the road. There are horses tethered with their owners beside them. There is the red of the Ogilvie’s livery. These, and the shop boards, give an impression of work and industry, in its positive Evangelical sense. The convict would have been sentenced to his work and that work would have been part of his reclamation, as it was for all. Children play in the streets and often appear pencilled at the edges of the watercolours. Men appear rarely; there are, in most paintings, women—a single lone woman makes her way to church, a woman in the street, two women stand and greet at Newbold Grange, Mary Bundock stands in front of Gordon Brook. The landscapes are feminised.Kindling and spreading light and knowledge in the pathless wilderness that have only been known to their Divine Maker through past centuries. The little cottage of which I have a sketch how does it convey cultivation of souls and minds and all good things into the far- off shores so recently unknown and unheard of.(A2269)

The drawings of the buildings and the straight lines of the roofs give the impression of an order and cleanliness that could only be projected onto the town. In contrast, Rose produced a map of Grafton with all the houses marked according to the rubric of respectability. This was drawn jaggedly, and one sees the curve of the Clarence and what Rose calls “the beautiful brush”—the scrub around the town. Again, the Aboriginal camp is not numbered or drawn. If the house contained “respectable” inhabitants it was noted. The appearance of the map gives the impression of the disorderliness with which Rose was confronted.

Watercolours produce a dreamy atmosphere, and this was a part of the Romantic influence on them. Rose’s garden in Grafton is a mass of flowers of all kinds, notably the exotic datura lily, appearing in two drawings of the front and back of the house, one in which the plant dominates. This lily was imported from South America and attests to the female interest in exotic plants in the colony, a scientific interest (Bracken et al. 2012, p. 10). Rose was pointing this out to the viewer—it is the only flower clearly visible. One gains from this flower a sense of the adventure in what Maria Cristall saw. She was clear that Rose was bringing light but also implying that a woman brings knowledge to the colony.

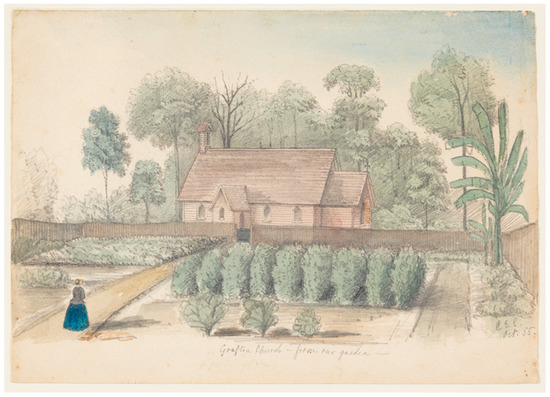

What is also notable is the height of the trees in the backgrounds of drawings of the cottage. These are native to the Clarence, but even the ferns were given heights well above their possible growth levels. The forest looms over the cottage and church (Figure 1 and Figure 2), which is in a clearing. “All good things” according to Maria Cristall, lie in the buildings, the cottage. This is the civilising impetus. Catherine Hall writes that civilization was regarded as a “gift” and a “responsibility” and that women were central to this mission. She writes that civilising “had to take place on multiple fronts, [including] the civilising work which women did on men, in the drawing room or back parlour” (Hall 2002, p. 13). This is how the illustration of the cottage spoke to Miss Cristall.

Figure 1.

4a. Grafton Church—from our garden—Oct.55. Grafton and the Clarence River, 1852–1901/sketches by Mrs Rose Elizabeth Selwyn (nee Rusden); State Library of New South Wales DL PX 6.

Figure 2.

‘1. Grafton Parsonage. April 1854′ Grafton and the Clarence River, 1852–1901/sketches by Mrs Rose Elizabeth Selwyn (nee Rusden); State Library of New South Wales DL PX 6.

The women in Rose’s watercolours are dressed in bonnets and gowns suitable for their public appearance; they clasp their hands, neatly walking to church or standing in front of their houses (Figure 1 and Figure 3). Their clothing is white and blue, the colours of innocence and the working blue of the colony (Maynard 1994, pp. 20–21). In later drawings, they are mauve (see Figure 3) and mauve seems to dominate—this shows Rose’s interest in fashion as “the new mauve” was invented in 1857 (Smithsonian “Making Colour” exhibition 2016, Smithsonian 2016) and became enormously popular in the colony in 1859, during which 173 references to it appear (Trove). Women are intensely present in the watercolours, and we catch them on their busy perambulations.

Figure 3.

Part of ‘72. Prince St. Grafton. 1857′ Grafton and the Clarence River, 1852–1901/sketches by Mrs Rose Elizabeth Selwyn (nee Rusden); State Library of New South Wales DL PX 6.

One could think that these watercolours reflect a particular colonising world view, most apparent in Maria Cristall’s evaluation of them. However, we cannot avoid the centrality of women to this landscape, women who were alone or together in twos. Women were both fulfilling a role expected of them and were also a strong presence on their own and this central focus on women would define Rose’s interests and her politics. For Rose, women were entirely separate from men in the way they thought.

7. Women-Centred Politics

Carol Mattingly has stressed the importance and imagination of women’s informal theological discussion groups in late nineteenth-century America (Mattingly 1998, p. 8). Rose Selwyn had her own circle of women with whom she discussed theology. That this theology was often “wild” was commented on by Arthur Selwyn who wrote to Rose on 26 July 1882 “tell S that if her opinion is correct, then there can be no such thing in the abstract as right or wrong, whether regards the worship of God, or anything else, but every man is to make for himself a right or wrong and no two the same. Is not this manifestly absurd?” (Selwyn 1899, p. 228). The thinking Arthur criticised derived from Walter Pater, the English critic, who believed all things were in constant flux and all truths were relative only to a particular moment. Pater was later critiqued by Thomas Arnold on “the baneful notion …every one may as well take his own way” (Houghton 1957, p. 16). The discussion by the women eludes the historian, but it does show the depth and complexity of the issues women dealt with among themselves.

There are references to Rose’s circle, Mrs Hoskins, Mrs Hogg, Mrs Isaacs, and Mrs Ogilvie, in a letter from Arthur Selwyn of 24 September 1851 (Selwyn 1899, p. 216). This list includes Eliza Armstrong, whose diary survives, and it shows the mysticism within Rose’s circle. Eliza Armstrong was deeply spiritual—she heard voices telling her where to find things she had lost; she thought her wayward children were saved from terrible accidents by unseen hands; and she had great faith in the powers of Mary the Mother of God (Muir and Armstrong 2008, p. 348). Eliza Armstrong followed the version of Anglicanism that emerged after the Pio Nono of 1854, whereby the Pope declared the Immaculate Conception of Mary; she was not born of Adam, but had “another nature” (Wheeler 2006, p. 233). While Evangelicals bitterly opposed such a pronouncement, Tractarians engaged with the aesthetics of Mary and Coventry Patmore wrote poetry concerning her presence, “milk sweet mother” (Wheeler 2006, p. 235).

The women listed by Arthur were also active in the Girl’s Friendly Society. This organization was begun in Sydney in January 1879, having been established in London in 1875. The G.F.S was concerned at the fates of the young, unaccompanied, single women arriving in the cities without guidance or assistance. It operated on two levels: firstly, through organizations of young women who met to maintain their own Christianity and fundraise, and secondly, through the operation of lodges for single women. Six-hundred young women passed through the rented lodges in William Street North Sydney between 1887 and 1920 (Beckenham 2006, p. 36). The aim of the society was “to band together as a society, ladies as associate leaders and girls as members for mutual help (religious and secular), for sympathy and prayer to encourage purity of life, dutifulness to parents, faithfulness to employers and thrift” (Beckenham 2006, p. 37). By 1883, there were eleven branches in Sydney and Rose Selwyn was involved in setting up the Newcastle branch. These organizations of women seem markedly independent of the dioceses. At one point, on the 26 May 1882, the Bishop suggested to Arthur Selwyn that Rose might like to report on their activities (Selwyn Letters 96). As Carol Mattingly has suggested, women’s organizations concerning purity, temperance, and the mitigation of the policing of prostitutes were important vectors for the development of women’s public speaking abilities (Mattingly 1998, p. 4). Rose began her public speaking on behalf of the Girls’ Friendly Society.

The reference “chaste” in Corporella is one of only two references we find to purity in Rose’s writings and speeches. When she lectured for the Girls’ Friendly Society at Newcastle, she emphasised not purity but the search for a husband, “you need not look for him, let him look for you” and “be sure that the one you choose is good [sic]” (Selwyn 1888). She was concerned that the Society was not friendly enough, “the members may be, and often are, in different ranks of society. But should that prevent them from being friendly?” Being critical of others’ dress, Rose thought a particular problem. An insight into the workings of the girl’s groups is gained in that criticism.

“Purity of life” was one of the aims of the G.F.S. Carroll Smith Rosenberg has written of the mid-century attention to purity in Jacksonian America. It derived from concerns about single young men crowding into the cities without moral guidance and resulted in an extensive discourse concerning bodily health, masturbation, and vegetarianism (Smith-Rosenberg 1978, p. 212). Helen Jones discusses similar influences in South Australia. Ann L. Scott has discussed the various connotations of purity in England at this time, one of which included the idea that women were more lawful than men and superior to men (Scott 1999, p. 637). Though the Girls’ Friendly Society sought to instil ideas of purity, Rose presents the city as a negative for unaccompanied girls who were easily corrupted. This was similar to the American writers’ perspective on males. On 9 November 1892, she wrote to her niece, Rose Scott, about her support for the push to have the age of consent raised. She related two stories, one about “a child of 13 or 14 attending a public school who was disgraced by a pupil teacher”. The girl was “taken home by broken-hearted parents, there to hide her shame. But the wretch went on teaching at the school”. At the same time, “a most immoral wretch, a Registrar took liberties with some girls immediately after he had married them”. Furthermore, when “poor erring girls had to go to the Registrar to register the death of their first child, he threatened to expose them publicly if they did not consent to his wickedness”. The Registrar was exposed but “two juries (composed of men [sic]) acquitted him”. Of the schoolteacher, Rose wrote, “if the law [sic] is amended, we women may lift our heads up high”. Rather than seeing the girls as objects of pity, a common position for nineteenth-century philanthropic women in Australia and an important component of early feminism (Windschuttle 1980, p. 15), Rose becomes one with them as “women” and this distinguishes Rose from many of her contemporaries. Thus, the body, the suffering female body, is key to her thinking and it is a body of which she is a part. The anger Rose shows in her underlining was also apparent in the frustration she felt with the limitations of Rose Scott using her salon to influence politicians. Rose Selwyn felt that women were struck “doubly dumb”, firstly in having no voice when abused and, secondly, unable to speak their own views in Parliament. Rose’s frustration with the powerlessness of women would lead her to advocate for women’s suffrage. One might suppose a conflict between the mystical ideals of her circle and the practical work of the Girls’ Friendly Society, but there was no indication of that. The move into public life afforded by that organization from her earlier mysticism was seamless. Rose’s identification with the suffering woman was a key component of her feminism and it distinguished her from the maternalism of philanthropy. Rose was about ‘we women” and this would come to incorporate the working woman.

8. The Working Woman and Corporella

On 17 February 1855, Ann Rusden wrote to her daughter about Rose’s servant, Mary, who had left “in an unpleasant manner”. Rose was full of self-reproaches as there had been a hostile argument. Ann agreed with Arthur that Mary “was wrong–indeed I think she herself would not have taken offence, had not her conscience smitten her”. A month later, on 27 March, Rose was still concerned, but Ann ‘was glad you are rid of her–your conscience was doubly tender–for you had to bear her weight, she seems to have had little weight of conscience upon herself!’ (ML MSS 38/77). It is surprising to find that in later life Rose wrote in On the Peculiar Fitness of Women that the working woman was a “heroine” in a climate where they were seen to be objects of pity to be redeemed. This change in perspective might be traced through her own experience as a mistress of a household, her short story Corporella, and her public writings on women. Rose was able to overcome the maternalism apparent in so many early feminists to identify with the working woman through the notion of the suffering body.

Corporella deals with an almost perfect relationship that goes drastically wrong when the Duke, the master of the house, decides that he does not want a servant getting the better of him. He begins to be harsh with Corporella, refusing her extra food, and working her very hard with little sleep.

Corporella reflects Rose’s inability to properly place a servant emotionally, or how to “be” with her, and such a tendency has been found among other women of the period, as Helen Pfeil has shown (Pfeil 2001, p. 1). The situation in Corporella is saved by a doctor who comes and sees that it is Corporella who must be nursed to health, not the Duke who magically recovers at the same time as Corporella. However, it is not enough to simply feed Corporella and let her sleep, she must be trained. This idea of the servant needing to be improved is essentially a maternalist view in which the culture and manners of the employer are something that need to be instilled in the lower classes (Magarey Passions 80). It is a view that would be abandoned by Rose in favour of an idea of equality. In 1887, she wrote to Lady Carrington, the Governor of New South Wales’ wife, that the Queen’s Fund, a charity commanding a budget of £80,000, be devoted to the alleviation of poverty among working class women. Lady Carrington replied in an undated letter appearing in Rose’s papers that she did not think the fund could be devoted to any particular class ‘as a class’ but rather that it should be disbursed on a case-by-case basis. Rose’s interest in working women was apparent at this early point and was to combine with her later feminism.

In the early 1890s, Rose corresponded with Emily Jones, a socialist and the editor of a magazine for women workers, A Threefold Cord. Jones wrote in a letter of 16 December 1890 that she herself favoured women “of different classes” drawing together in the Mother’s Union, Women’s League, or Union of Workers, as “those who pray and work together can hardly think badly of each other”. Emily wrote in an undated letter “where there is sympathy [sic] mothers will stand a great deal of plain talk, even from an unmarried woman like myself. If you don’t preach at them it is very easy to reach them”. Emily wanted to make meetings largely devotional and then “tack out questions relating to the building up of a pure social and family life”. In an undated letter, she related what such groups of women would do. Their aims would be “Vigilance work–the keeping up of Police to their duty, the reform of the laws, the promotion of the return of the best citizens to positions of importance in municipal and colonial government work, high minded men”. Women were certainly engaged in the public world, but they were to be engaged in a separate capacity to men. Women only groups thus formed a beginning for the conceptualisation of a public woman. Emily Jones’ emphatic underlining, her sense of imperative and urgency, evolved from contemplating “the fallen woman” and the pressing need to save her. Rose developed a similar emphatic tone, except she identified with the working woman, and in her own publications and speeches moved further than Emily Jones in advocating for women’s political involvement and their representation.

9. Rose and the Public Woman

Rose gave several speeches concerning the rights of women. She was elected president of the Newcastle Women’s Suffrage League in July 1894 and this appointment was reported in the Sydney Morning Herald on the 21st of July. On the Peculiar Fitness of women to Help in the Government of the Nation was given for the Women’s Suffrage League at Newcastle in July 1897 and was reported in the Sydney Morning Herald on the 2nd of July. Should women be jurors was reported briefly as part of a debate in the Daily Telegraph of the 12th November 1897. These speeches, and her involvement with the Girls’ Friendly Society, created her as a public woman. The speeches were part of a successful broader movement for women’s suffrage in Australia (Magarey 2001) and Rose and her niece, Rose Scott, were major figures in Newcastle and Sydney (Allen 1994). Women were not able to be jurors in New South Wales until 1947. Rose Selwyn’s arguments in Should women be jurors? are indicative of the modernity of her ideas in her own political climate. The content of the speeches offer the reader Rose’s thinking. It was a particularly new idea of the public that Rose introduced, one that would be female shaped.

Rose used rhetorical techniques in all her public addresses. She proceeded by eutrepismus, or listing her points, and exempla, or providing examples, to illustrate her argument. Listing linked to reason and mathematics; examples were designed to raise the sympathy or empathy of the listener—they dealt with feeling. In Should women be jurors?, Rose used the example of an 1886 woman tried for murder, “Mrs Bartlett”, who was “nearly condemned because men’s experience “did not help them” to adjudicate on the case. Mrs Bartlett was “worn down with nursing” and “women know what it is to be worn with nursing, mothers [sic]even can hardly keep awake”. The jurors thought she could have got up to see to her husband who had overdosed on chloroform—women would have known “she simply couldn’t.”

For Rose, women’s special experience would be useful in the work of a jury. She argued that “she did not want to see a jury of women only”. Rather, women and men must work to improve juries and to broaden views. Women were “keener and perceptive” and “conscientious, careful and sensible”. Women “make men talk and think more decently”. Thus, Rose argued not that women were equal to men but were in some ways superior and their difference was what would change the nature of the jury.

In On the Peculiar Fitness of women to Help in the Government of the Nation (1897), the exempla Rose used were from the Bible and from history. She also used an appeal to authority—referring to “Liddon, Forsythe, Ruskin and Mrs Fawcett”. The paper gave evidence for the inclusion of women in “public government”. Rose uses hypophora, or the asking and answering of questions, in this speech. What this technique does is to engage the listener in a kind of equality of exchange and suggests exploration rather than certainty.

Rose builds up a notion, a persona for the public woman. She does this first by taking away the idea of the “home” from the idea of women, suggesting it is illogical—“what can they do who have no house to keep?” She then argues from the ground of the authority of the bible—Old Testament and New. She discounts St Paul’s and St Peter’s view on women as being “in subjection” because the reason for such a decision “as well shown by Fordyce” was the concern that Christian women should not be identified with Greek or Roman women lest the liberty of the sober Christian woman be affected. Rose reminded her listeners that St Paul, despite his views on subjection, had in fact written that “in Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek, neither bond or free neither male nor female–but all are one”. God spoke to man and woman in the Garden of Eden, not just to man. This is a form of liberation theology, but it also empties and evens the ground between male and female. Rose proceeded through a discussion of biblical women noting their self-assertion and their action.

Queens were then discussed, as “while the historian stands aghast at the private life of the Russian empress [Catherine] she is only mildly scandalized by Charles V or Henry IV”. The historian as a “she” is perhaps a slip of the pen, but it fits with Rose’s descriptions of these intellectual and brave women who led their societies. Elizabeth I was “a great statesman” and Queen Victoria “created modern constitutionalism”. In all these accounts, women are moving and active, and it is their presence and activeness that created the states in which they lived. This is an utterly woman-centred narrative—even the historian is a “she”. What Rose valued in all these women was their intellectualism and their bravery.

Rose moves on to the “qualities” of women. Are they, she asks, “the same as men?” No. Women possessed the passive virtues “faith, hope, love, long suffering, gentleness, meekness, goodness, patience and temperance”. All these virtues were present in Queen Victoria and they had been “singularly adapted to contribute to the happiness and prosperity of the people over which she ruled”. Rose added “the same result could not have been obtained by any man”. In this section of her speech, women are indeed pitted against men. The Queen was responsible for great achievements, and no man was involved. These results were specific to women and their different and separate nature. For Rose, the public woman who seeks to govern is something apart from men. Her virtues are listed, and added to this must be the intellectualism and bravery shown by women in history.

Rose concludes her speech with a reference to purity, “The friendless young man, who in Newcastle or Sydney, amid temptation dares to lead a really pure life, is a Christian hero. The humble maid of all work, who serves a hard master or mistress faithfully for Christ’s sake is a Christian heroine”. This is a reference to suffering, but is also an erasure of class, a tendency present in her thought and a reduction of male and female to the “all” in Genesis and the teachings of Christ. “The delicately bred lady who gives up the attractions of society to nurse fever patients or to teach a fallen sister that it is possible to be pure again” is also a heroine. In this last section, Rose might seem to be conforming to the ideals of the Purity Leagues discussed by Helen Jones, but it is also a levelling of the strata of society and has its origin in Emily Jones’ socialism.

Rose relied on the power and strength of those Purity Leagues to back her argument for women in government and to introduce a point at the end of her speech with which no right-thinking Christian would dare to disagree. In its seeking to alter and change public life through the presence of these different women, who had in fact been shown to be better at governing than men, Rose was indeed expressing a radical viewpoint.

10. Orientalist Feminism

As Aileen Moreton Robinson has pointed out, the dominant discourse concerning relations between Australian feminism and Aboriginal people has been the notion of ‘civilising’ which continues today (Moreton Robinson 2021, p. 1). Rose was certainly caught in this discourse, and she advocated for the new regime of reserve confinement of Indigenous people in the early twentieth century. However, her feminism, based on the idea of suffering, was not at all extended to Aboriginal people. This made her writing on Aboriginal people quite separate from all her work discussed so far, and the tangled influences on it were possibly shaped by her own family’s involvement in the violence of the occupation.

In the years Rose was in Grafton, punitive raids were carried out by magistrates on camps of their own servants (Tindal). These magistrates formed a central part of the Selwyn’s social circle. Rose lived among violent people and was a part of a colonizing culture. Rose also had a number of Aboriginal servants, beginning with a Geoffrey—as Ann wrote on 6 June 1855 and Arthur Selwyn indicates that Geoffrey was still with them on 19 July 1859 (Selwyn 1899, p. 120). Her paper on The Aborigines in no way refers to colonial violence but proceeds with an exemplum of her “remembered” experience with Gumbayngyirr, Yaegl, and Bunjalung people. Rose created a narrative of condescending happiness in order to argue in favour of Aboriginal people, not for their rights, but for their containment on missions and reserves.

It is not possible to describe Rose as one of the women working with Aboriginal people, as set out in the collection Uncommon Ground (Cole et al. 2005). Rose does not appear to have worked with and for Aboriginal people. Rather, she negotiated them as servants and her speech The Aborigines advocates for the new surveillance state that Aboriginal people would find themselves in from the early 1900s. There may be some comparison to the work on missionary women undertaken by Cruickshank and Grimshaw (Cruickshank and Grimshaw 2019). Actual ‘civilising’ programs were sometimes contradictory and confusing for women who undertook missionary, anthropological, or charity work, sometimes creating a warped and imaginative realpolitik. This confusion is apparent in Rose’s speech, which raises more questions than it answers. Rose’s description of her remembered life follows the template of many women who would designate themselves “pioneer,” including Charlotte May Wright (Wright 1985) and Mary Bundock (ML A3969), both of whom published their reminiscences at the same time as Rose produced her paper. All of them may be read for the occasional slips and erasures that begin to show us some of the realpolitick of this part of the north of New South Wales.

Rose uses exempla of stories from the Aboriginal camp “very near the township” to make three listed points about Aboriginal people. These are, “(1) They are sympathetic (2) They are full of innocent merriment (3) They are kind to each other”. Rose is endowing Aboriginal people with humanity in disagreement with persons who would argue that Aboriginal people were not kind, were without humour or sympathy, and were not human. The examples she gives are stories from her own life that are designed to amuse the audience. Rose is the hidden witness to a game played by two unnamed young girls where the relationship between mistress and servant was parodied. “Mrs White was seated on a log of wood, her face steadily fixed in a scowl of anger. Miss Black approached her humbly with a few little sticks in her hand “Please Missus here waddy” Mrs White scowled in reply, crossly ordering more waddy to which Miss Black humbly agreed, but they had to stop and relieve their feelings by merry laughter”. The girls swapped roles. “This went on for some time. Patta (food) was promised in return for more sticks–but the promise was broken which amused them excessively”. This account of a parody, Rose indicates, is proof of her point that “they are full of innocent merriment”, but it also has another message of cruelty that Rose says she is ashamed of concerning the withholding of food, that was not directly addressed by her.

Her stories of King Sandy, “the Dean’s own man, he called him master”, involves Sandy being given a suit of clothes “in which he looked well and happy”, but he appeared the next day without them. When asked, he said “I gave “em to Jimmy…you give me more”. Jimmy “was not allowed to keep the clothes” for Sandy had many friends who would all expect the same”. This story also has another meaning concerning the nature of the gift which, under the giver’s control, was not truly given but taken back by Dean Selwyn, so the gift was false.

Sandy was invoked in another story where he “was temporary king of the kitchen” and “was careful to do what he was told…his Master put up nails telling him one was for the knife cloth, another for the pudding cloth and so on”. However, the Selwyns have a visitor who was untidy and put the cloths anywhere. Sandy said “I say missus that fellow in house is no good. I asked what he meant. He said “Master say this [sic] nail knife cloth, that pudding cloth, but that fellow in house come and knock them all about”. Again, this is a humorous tale, in a way deriding the “king”, but it is also a story of white inconstancy; the rules are broken without concern.

White inconstancy, falsity, and cruelty have long been stressed by Aboriginal people in Australia as endemic in the policies developed for them (Moses 2013, p. 54; Personal Stories n.d.). Rose’s narrative derives directly from squatter humour in their own tales of cruelty, particularly apparent in columns from the Namoi River in the Maitland Mercury in the 1840s and 1850s. When she said that King Sandy reminded her only once of his royal status “I say Missus, look here, all this belong to me”, she is invoking the extensive humour about Kings among squatters, as well as reporting a statement about possession. In a sense, she is simply relating a squatter discourse that recognised Aboriginal politics and sometimes sought to utilise it (Connors 2017). However, a woman who was quick to identify the suffering body in all women did not at all extend such a view to Aboriginal women, but rather she was caught in the discourse of the innocent “noble savage” deriving from Rousseau in which Indigenous people were quiet, innocent, at one with nature, and child-like. According to Stephen Muecke this is the major “positive” discourse available to Australians (Muecke 1992, p. 19). In another sense, Rose is a vehicle for Aboriginal readings of the colonists, in that it identifies non-Aboriginal hypocrisy and cruelty.

In support of the “noble savage” and in opposition to the idea of race, her paper uses material from science that argues Aboriginal people are closely related to Caucasians and in fact have a superior physiognomy. She uses A.R Wallace and his Australasians, and “the evidence of Dr Pritchard with his skull measuring to show that there is “no material differences” between Aboriginal people and other races. This is to contradict the powerful racist language in which inferiority was supposedly scientifically proven.

What was valued in the paper was the civilising impulse of the young squatter women of the Clarence who set up schools for Aboriginal children, Miss Tindal and “Mrs Hawkins Smith’s good sister Miss Rothery”. Miss Rothery had shown letters to Rose which the Aboriginal children had written to her. What was also valued was the work of Ernest Gribble in the north of Australia who had found “a fine race of 200 people on the Mitchell River”. He had “wonderful success” and the “whole atmosphere of the place is religious”. Rose also mentioned that Aboriginal people had “their own parliament and court” that “they hold together”. Though this was not explained further, the idea of “parliament” relating to Aboriginal people was suggestive and Rose here was suggesting other models of Aboriginal organization, albeit under the eye of Gribble. Again, we detect another message in her talk, the association of the word “parliament” with Aboriginal people.

The contradictions found in Rose’s position on Aboriginal people are to be found elsewhere in the late nineteenth century. Aboriginal people occupied a shifting position between savage, noble savage, original owners, and people needing to be civilised. These interpretations appeared alongside their own political arguments (Goodall 1996). Such thinking resulted in experiments and schemes (Curthoys and Mitchell 2018, pp. 50–51), such as Gribble’s at Yarrabah, which has been portrayed by Ann McGrath (McGrath 2015, p. 104). Nevertheless, in The Aborigines, another speaking voice made its appearance, that of Aboriginal people themselves, either intentionally or through the results of close living with “masters”. While Rose may be showing some of the complexity of the squatter character, she also undermined the power those squatters had.

Because of its argument for reserves controlled by people like Gribble, we must still see Rose’s feminism as part of the apparatus of control over Indigenous peoples, and as orientalist, in that it privileges the white view on the “civilising” process and a perspective on the “uncivilised” similar to that discussed by Joyce Zonana in her work on Charlotte Bronte (Zonana 1993 p. 592). Aboriginal people were, according to Rose, to be altered so much so that Yarrabah was almost better than white Australia in its “religious atmosphere, its quiet devotion”.

11. Conclusions

Piecing together a genealogy of Rose Selwyn’s intellectual life shows how an individual feminist made sense of her world and also sought to change it completely. Rose drew from contemporary strands of thinking that questioned reason’s control in the world, in a way that emphasised the suffering body and the physical body. The making of Rose Selwyn is a story of anxiety. The body comes into being because of concerns with death and the void. Would your soul mate remember you in heaven or would he or she forget as time was erased? How does the body, stuck and confined in the coffin, relate to the soul? The body lies waiting, hearing the wails of the damned. Thoughts of the body and suffering led to contemplation of the female body, despoiled by wretched men, but rather than simply saving such women, Rose became one with them in their suffering. The working woman was a heroine.

Rose attained this way of being through several contemporary influences—the mysticism of Tractarianism, a concern with death and its meanings, an interest in the literary edges of the world, a concern with the suffering body, with pain, and mortality deriving from Evangelical thought, and a passion for women and a woman-centred world. From these tangled contemporary concerns, she made a feminism for all non–Aboriginal women.

Those who suffered most, particularly at the hands of Rose’s social circle—Aboriginal people—were not thought of in terms of suffering. Despite this, however, Rose voiced Aboriginal readings of non-Aboriginal people and their central immorality, and this shows the conflicted position she was in as a part of squatter society. Rose’s worldview was one of possibilities signified by her use of the term ‘parliament’ to describe Aboriginal organization.

Traces of ideas are not direct portrayals of a person’s philosophical or ethical position. The latter may be spelt out in letters or recorded in diaries, carefully argued. We are made of lines of poetry, scraps of sections of books, sewn in ivy leaves. These, forgotten or remembered, make a sensibility of which we are not always or entirely aware. In terms of a public woman, who was prepared to make a different public altogether, Rose Selwyn was created by several currents of contemporary thinking. She also produced a colonial female way of being alongside other feminists of the period.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources

Daily Telegraph.Maitland Mercury.Mary Bundock, Notes on the Richmond River Blacks, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library (hereafter ML) ML A3969.Scott Family Papers ML 2268 ML2269; ML MSS 38/77.Rose Selwyn Memoirs ML A1616.Rose Selwyn Grafton and the Clarence River, 1852-1901/sketches by Mrs Rose Elizabeth Selwyn (nee Rusden) State Library of New South Wales, DL PX 62.Selwyn Papers MSS 201/3.Sydney Morning Herald.Tindal Papers ML A2068.Trove online National Library of Australia.alc.org.au/land_council/unkya (accessed on 22 June 2022) for Aboriginal History Gumbayngirr.alc.org.au/land_council/yaegl/ (accessed on 22 June 2022) for Aboriginal History Yaegl.uurrbay.org.au/languages/Bunjalung (accessed on 22 June 2022) for Aboriginal History Bunjalung.Secondary Sources

- Adams, William Henry Davenport. 1863. Nelson’s Handbook to the Isle of Wight. Edinburgh: T Nelson and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Judith. A. 1994. Rose Scott, Vision and Revision in Feminism. Oxford: Melbourne. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Amanda Jane. 2003. A Study of Eliza Broadhurst”s Nineteenth Century Literary Cuttings from All Sources. Report. Sydney: Department of Maritime Archaeology, National Australian Maritime Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Beckenham, Evelyn. 2006. A Faithful Journey, the story of the G.F.S in the Diocese of Sydney. Sydney: Self Published. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Peter. 1978. “A return to Berloiz”s “Retour à la Vie”. The Musical Quarterly 64: 354–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, Illana M. 2013. Ethics and Economics in Mid-Century Novels. Michigan: Ohio State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bracken, Susan, Andrea Caldy, and Adrianna Turpin. 2012. Women Patrons and Collectors. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars. [Google Scholar]

- Bradstock, Margaret, and Louise Wakeling. 1991. Rattling the Orthodoxies, A Life Of Ada Cambridge. Sydney: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Bullen, Barrie J. 2011. Rosseti, Painter and Poet. London: Francis Lincoln. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Paula Jane. 2022. Women and Intellectual Life in New South Wales 1835–1868 Ann Rusden. Australasian Journal of Victorian Studies 26: 42–62. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, William Kingdon. 1877. The Ethics of Belief. London: The Perfect Library. [Google Scholar]

- Cobham Brewer, Ebenezer. 1858. A Guide to the Mythology, History and Literature of Ancient Greece. London: Jarold and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Anna, Haskins Victoria, and Paisley Fiona. 2005. Uncommon Ground. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connors, Libby. 2017. Warrior. Sydney: Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, Jude. 2017. Two Roses: Two Radical Hunter Valley Women: Rose Selwyn and Rose Scott. Available online: https://hunterlivinghistories.com/2017/05/15/two-roses/ (accessed on 9 October 2021).

- Cruickshank, Joanna, and Patricia Grimshaw. 2019. White Women, Aboriginal Missions and Australian Settler Governments. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Curthoys, Ann, and Jessie Mitchell. 2018. Taking Liberty, Indigenous Rights and Settler Self Government in Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daly Goggin, Maureen. 2017. “Fabricating Identity: Janie Terrero’s 1912 Embroidered English Suffrage Signature Handkerchief” Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Foukes Tobin. Women and Things 1750–1950. London: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Dever, Mary Ann, Sally Newman, and Ann Vickery. 2009. The Intimate Archive: Journeys through Private Papers. Canberra: National Library of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, Joy. 2001. Divine Feminine. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins. [Google Scholar]

- Flint, Kate. 2000. Victorians and the Visual Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geschiere, Peter. 1998. “Globalization and the Power of Indeterminate Meaning: Witchcraft and Spirit Cults in Africa and East Asia” in Meyer Birgit and Peter Geschiere. In Globalization and Identity. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 211–37. [Google Scholar]

- Goodall, Heather. 1996. Invasion to Embassy. Sydney: Sydney University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Catherine. 2002. Civilising Subjects, Metropole and Colony in the English Imagination 1830–1867. London: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard, David. 1993. The Anglo-Catholic Tradition in Australian Anglicanism. Paper presented at Studying Australian Christianity Conference, Sydney, Australia, July 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, Boyd. 1988. The Age of Atonement, The Influence of Evangelicalism on Social and Economic Thought, 1795–1865. Oxford: Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, Walter E. 1957. The Victorian Frame of Mind. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Janes, Dominic. 2009. Victorian Reformation 1840–1860. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Helen. 1986. In Her Own Name, Women in South Australia. Adelaide: Wakefield. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Lawrence. 1995. Gender and the Public/Private Distinction in the Eighteenth Century: Some Questions about Evidence and Analytic Procedure. Eighteenth Century Studies 29: 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magarey, Susan. 2001. Passions of the First Wave Feminists. Sydney: UNSW Press. [Google Scholar]

- Magarey, Susan. 2010. Unbridling the Tongues of Women, A Biography of Catherine Helen Spence. Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, Henry. 1845. Sermon X The City of God. Available online: ccel.org/ccel/manning_henry/sermons03.iii.x.html (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Masur, Margo. 2015. “Inhumanly Beautiful”: The Aesthetics of the Nineteenth-Century Deathbed Scene. Ph.D. thesis, Buffalo State College, Buffalo, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, Brian. 1998. Louisa. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly, Carol. 1998. Well Tempered Women, Nineteenth Century Temperence Rhetoric. Edwardsville: Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, Margaret. 1994. Fashioned From Penury. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, Ann. 2015. Illicit Love: Interracial Sex and Marriage in the United States and Australia. Omaha: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, Julie, and Jude Conway. 2017. Intimate, Imperial, Intergenerational: Settler Women’s Mobilities and Gender Politics in Newcastle and the Hunter Valley. Journal of Australian Colonial History 19: 161–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mecklenburg-Faenger, Amy. 2009. “Material Histories: The Scrapbooks of Progressive Era Women’s Organizations, 1875–1930” Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Foukes Tobin. In Women and Things 1750–1950. London: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Mecklenburg-Faenger, Amy. 2012. Trifles, abominations, and literary gossip: Gendered rhetoric and nineteenth-century scrapbooks. In Genders 1998–2018. Boulder: University of Colorado Boulder. [Google Scholar]

- Moreton Robinson, Aileen. 2021. Talkin’ Up to the White Woman. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moses, Dirk. 2013. Genocide. Australian Humanities Review 55: 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Muecke, Stephen. 1992. Available Discourses on Aborigines. In Textual Spaces. Edited by Peter Botsman. Sydney: UNSW Press, pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, Thomas, and David Armstrong. 2008. Richard Ramsey Armstrong’s Book of His Adventures. Sydney: Self-Published. [Google Scholar]

- Personal Stories. n.d. National Museum of Australia. Available online: nma.gov.au/exhibitions/from-little-things-big-things-grow/personal-stories (accessed on 29 October 2022).

- Pettitt, Claire. 2016. Topos, Taxonomy and Travel in Nineteenth Century Women’s Scrapbooks. In Travel Writing, Visual Culture and Form. Edited by Mary Henes and Brian H. Murray. London: Palgrave, pp. 1760–1960. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeil, Helen. 2001. The Last Piece of Furniture Procured: Some Mistresses Perspectives on the Mistress Servant Relationship, 1870–1900. Lilith 10: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Stephen. 1964. The Squatting Age in Australia. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, Jill. 1986. Beyond Belief. Sydney: New South Wales University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schramm, Jan Melissa. 2012. Atonement and Self Sacrifice in Nineteenth Century Narrative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schramm, Jan Melissa. 2019. Censorship and the Representation of the Sacred in Nineteenth Century England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Ann L. 1999. Physical Purity, Feminism and State Medicine in late Nineteenth Century England. Women’s History Review 8: 626–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, Rose. 1888. Address to the Girls’ Friendly Society, East Maitland. Newcastle: Girl’s Friendly Society. [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn, Rose. 1899. Letters of Arthur Selwyn. Sydney: Privately Published in Limited Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, David. W. 1990. Victorians and Mystery. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, Susan. 1993. “The Woman’s Voice on sexuality” in Susan Magarey, Sue Rowley and Susan Sheridan. In Debutante Nation, Feminism Contests the 1890s. Sydney: Allen and Unwin, pp. 114–124. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Rosenberg, Carroll. 1978. Sex as Symbol in Victorian Purity: An Ethnohistorical Analysis of Jacksonian America Authors. American Journal of Sociology 84: 212–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithsonian. 2016. Available online: https://library.si.edu/exhibition/color-in-a-new-light/making (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Stephen, Leslie, and Sidney Lee. 1885. Dictionary of National Biography. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Symes, Ruth. 1995. Educating Women: The Perceptress and Her Pen, 1780–1820. Ph.D. thesis, University of York, York, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, Audrey. 1991. Ada Cambridge, Her Life and Work 1844–1926. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Jeremy. 1990. Selected Works. New Jersey: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vivers, Meg. 2013. Castle to Colony. Brisbane: Self Published. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, Michael. 2006. The Old Enemies, Catholic and Protestant in Nineteenth Century English Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Windschuttle, Elizabeth, ed. 1980. Women, Class and History. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Charlotte May. 1985. Memories of Far-Off Days. Armidale: Self-Published Peter Wright. [Google Scholar]

- Zonana, Joyce. 1993. The Sultan and the Slave: Feminist Orientalism and the Structure of “Jane Eyre”. Signs 18: 592–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).