Since the critiques of the 1991 Census ethnic group question, made on the grounds that it avoided ‘race’ while using colour terms and the ‘sanitised’ concept of ethnic group, there has not been a focused or sustained call for the use of ‘race’ in census and other official contexts. However, this has recently changed. Taking in the substantial changes to the ethnic group question in the 2001 and 2011 censuses (including the addition of ‘mixed’ categorisation), an influential paper by

Song (

2018, p. 1138) offers a wider questioning of official census practices with respect to ‘race’, including the ‘striking’ ‘avoidance of “race” by the ONS’. This critique is articulated with respect to the ONS’s ‘measurement of “mixed” people and “inter-ethnic unions” in the British census’, which ‘seriously compromises our ability to map racially distinctive ways in which mixed relationships occur, as well as our understanding of the racial diversity contained within the category “mixed”’. ‘Interracial’ unions are defined as ‘involving people seen as belonging to visibly different “races”’ (p. 1139), with racial categories such as white, black, and Asian as opposed to ‘the racial overlap between, say, a black Caribbean and black African couple’ (p. 1140). Further, it is argued that ‘race’ is central to understandings of racism. However, Song gives no indication of how ‘race’ could be operationalised in the census.

Three challenges to the UK’s official categorisation by ethnic group can, therefore, be identified: the challenge of ‘mixed race’; the challenge of interracial unions; and the challenge posed by ‘race’s relationship with racism’.

4.1. The Challenge of ‘Mixed Race’

‘Race’, as exemplified by the term ‘mixed race’, does present some challenges to the use in censuses and official data collections of ethnic group and the avoidance of ‘race’. There is a notable preference for the term ‘mixed race’ amongst this population and some use by government departments. However, when looked at in context and in detail, these challenges are not persuasive as ‘disrupters’ of current census terminology.

In the England and Wales 2001 Census, the ONS used the umbrella term ‘Mixed’ for its categorisation, which comprised three exact combinations (‘White and Black Caribbean’, ‘White and Black African’, and ‘White and Asian’) and an open response ‘Any other Mixed background’. In the 2011 Census, the mixed section was relabelled ‘Mixed/multiple ethnic groups’ and the free-text option ‘Any other Mixed/multiple ethnic background’ on the ground that not all form-fillers were content with the term ‘mixed’, although 80 percent of data users in a 2007 consultation found the term ‘mixed’ acceptable. Clearly, the truncated term ‘Mixed’ used in 2001 does not foreclose extended descriptors such as ‘mixed race’, ‘mixed heritage’, and ‘mixed origins’ and it is unlikely that the 2011 label would have done so. ‘Mixed’ was the term used throughout the ONS’s publication

Who are the ‘Mixed’ ethnic group (

Bradford 2006), to the exclusion of ‘mixed race’. This was not the first time that the term ‘mixed group’ had been used in the context of reporting official data on Britain’s ethnic groups (

Joshi 1989). The only use of ‘mixed race’ in the context of the census, it will be recalled, was in the Home Affairs Sub-Committee’s suggested 1983 question.

4.1.1. Saliency of ‘Mixed Race’

There is an evidence base that provides grounds for recognising the saliency of ‘mixed race’ as the term of choice amongst the wider population and young people who are described by such terms. In an attempt to identify respondents’ preferences for generic terms for ‘mixed race’, two surveys of ‘mixed race’ people (a convenience sample of the general population,

n = 76, and a structured sample of 18–25-year-olds in higher/further education institutions,

n = 326) were undertaken (

Aspinall 2009;

Aspinall and Song 2013). Respondents were asked which of a list of general terms they preferred and were invited to select all that apply. The most popular general term of choice amongst respondents was ‘mixed race’, with just over half (54%) the respondents in the student survey selecting this. Other terms that attracted much less support amongst students were ‘mixed heritage’ (18%), ‘mixed origins’ (16%), and ‘mixed parentage’ (13%). Terms indicating only two groups, ‘mixed parentage’, ‘dual heritage’ (12%), and ‘biracial’ (4%) were the least popular for students. However, the set did not include the census terms of ‘mixed’ and ‘mixed/multiple ethnic groups’. ‘Mixed race’ was also the preferred term (42%) amongst the general population sample.

There is other evidence that the ‘politically correct’ terms ‘dual heritage’ and ‘mixed heritage’ lack currency amongst ‘mixed race’ people, specifically, amongst pupil and parent respondents in surveys.

Tikly et al. (

2004) stated that: ‘… we use the term ‘mixed heritage’ rather than the more commonly used term ‘mixed race’ to refer to those pupils and people who identify themselves, or are identified, as having a distinct sense of a dual or mixed, rather than ‘mono heritage’ … The decision to use ‘mixed heritage’ instead of ‘mixed race’ was adopted in order to ensure consistency of terminology on DfES literature. However, it was apparent in interviews that the majority of pupil and parent respondents used ‘mixed race’, whilst some were content to use ‘half caste’. For most pupils and parents, ‘mixed heritage’ was not a term that they were familiar with and were less comfortable with its initial use in the interview’ (2004, p. 17).

In spite of the saliency of ‘mixed race’, practice varies in official contexts. An analysis of terminology (‘mixed parentage’, ‘mixed race’, ‘mixed origins’, ‘dual heritage’, and ‘mixed heritage’) on government websites, undertaken as a point count in 2008 (

Aspinall 2009), revealed that a plurality of terms was used. In the Department of Children, Schools, and Families (which replaced the Department for Education and Skills (DfES) in 2007), there were 22 occurrences of ‘mixed race’, a number exceeded by the relatively recent, politically correct terms of ‘dual heritage’ (

n = 29) and ‘mixed heritage’ (

n = 49). However, ‘mixed race’ was the most frequently used term by the Home Office (

n = 28) responsible for immigration, security, and law and order and the Department of Communities and Local Government (

n = 67). The consolidation in 2012 of Department websites into the generic

https://www.gov.uk (accessed on 1 July 2021) search engine precludes more recent analysis.

4.1.2. Clarity of Definition of ‘Mixed’

Arguments that the ‘ONS does not provide a clear definition of “Mixed”’ (

Song 2018, p. 1140) seem perhaps too critical. The three specific exact combinations listed under the section heading utilise the pan-ethnicities ‘White’, ‘Black’ (split into ‘Black Caribbean’ and ‘Black African’), and ‘Asian’, and these broad ethnic groups could equally be described in general discourse as ‘races’ given the interchangeability of the terminology in the UK or subsumption of ‘race’ within the concept of ethnic group. Indeed, the OECD refers to these options as ‘a variety of race combinations’ (

Balestra and Fleischer 2018, p. 33). Further, in guidance for census form-fillers, the

Office for National Statistics (

2021) states: ‘If you feel you belong to more than one ethnic background from the sections, select “Mixed or Multiple ethnic group”’, clarifying that ‘It’s up to you how you answer this question’. The label ‘mixed/multiple ethnic groups’ and the predesignated, exact combination category options encompassed by this section label make its meaning explicit. For example,

Bradford (

2006) noted that ‘The ethnic origins of the three specified Mixed groups in England and Wales … are self-explanatory to a greater or lesser extent’. They were selected as they were the most frequent ‘mixed’ write-in responses in the 1991 Census: ‘Black/White’, 54,569; ‘Asian/White’, 61,874; and ‘Other Mixed’, 112,061 (

OPCS/GRO(S) 1993). Only 3776 persons gave a ‘Mixed White’ description.

Moreover, the wording of the ‘Mixed’ free-text option resonates with this self-identification question’s instruction to form-fillers to ‘tick one box to best describe your ethnic group or background’. The ‘Mixed’ categorisation has now been used for two decades in a plethora of data collection and ethnic monitoring forms as well as the three England and Wales decennial censuses (2001, 2011, and 2021). It is difficult to see how this set of mixed/multiple options could be misconstrued as, for example, including disparate mixed white options; these are found in the responses to the ‘Any other White background’ write-in option (coded in 2011 as ‘White: European Mixed’ (

n = 304,865), one of the largest White write-in subgroups, after ‘Polish’ (

n = 510,561) and ‘Other Western Europe’ (

n = 396,571)) as such respondents do not see themselves as ‘Mixed/Multiple’. Further, it is unclear how substantially the responses to the category options would differ if this set was termed ‘mixed race’, especially as cognitive research undertaken by the ONS indicates that respondents’ choices are primarily driven by the category options rather than the other apparatus surrounding the question, a finding also common to US tests (

Kelly et al. 2017).

4.1.3. A Critique Based on Conceptualisation but Omitting Operationalisation

While critiques of census categorisation practices generally encompass conceptualisation, operationalisation, and analysis,

Song’s (

2018) challenge to ‘Mixed’ is solely conceptual. The use of ‘mixed race’ rather than ‘mixed/multiple ethnic groups’ would introduce to the question another conceptual base in addition to ethnic group, thereby disrupting the intended meaning of the question and creating ambiguity. In the same way, in its pre-2011 review of the ‘mixed’ label, the ONS indicated it was ‘concerned that introducing the term heritage may impact on the overall understanding of the question’ when the candidate of ‘mixed heritage’ was considered. Or as

López and Hogan (

2021, p. 9) put it with respect to the US 2020 Census: ‘A basic introductory statistics class would advise against asking about two concepts race and origin… in one question’. An argument that the saliency of the term ‘mixed race’ in the population, 2.2% of whom identified as ‘mixed/multiple’ in 2011, should drive the choice of conceptual base for the question as a whole is unreasonable, especially as the ‘mixed’ label does not close down an interpretation as ‘mixed race’.

As Song’s critique argues that both ‘race’ and ‘ethnicity’ concepts are necessary, the census would need to ask an additional question on ‘race’ listing the five pan-ethnicities (‘White’, ‘Mixed’, ‘Asian’, ‘Black’, and ‘Other’). The rationale for this is elusive. The US Census Bureau labels its question ‘race’ as, historically and unlike Britain, this has been the salient concept. However, it states that the options listed (these numbering 15 in the 2000 and 2010 Censuses) are, in fact, ‘racial and national origin or socio-cultural groups’. This is an example of what

Jenkins (

1996) refers to as the nominal and the virtual. The nominal, ‘a matter of name or category alone’, differs with respect to British and US census practices, but the virtual (sometimes called the ‘functional’), what the name means in terms of conceptualisation, reveals commonalities with respect to the listing of national and socio-cultural origin options (the notable difference being that the Census Bureau treats ‘race’ and ethnicity as different types of identity, the latter targeting only one ethnic group, Hispanics). Asking an additional census ‘race’ question, improbable because of the ONS’s resistance to the term, but also space constraints on the form, is likely to confuse form-fillers as they would be completing the ethnic group question whose 18 tick options in 2011 are embedded in these same section headings. A further drawback may be an undercount on some of the ‘race’ options but an overcount on ‘Other’: many respondents do not feel that the broad term ‘Asian’ satisfactorily describes them, while some Black Africans object to the use of the ‘Black’ pan-ethnicity as it denies their cultural Africanness. By contrast, the broad ethnic categories are counts summed from the tick box responses.

For significant changes to be countenanced in the ethnic group question, the ONS first establishes whether a prima facie case can be made, based on user demand as expressed in an initial consultation exercise with stakeholders and wider significant demands within the general public. In recent census development programmes, no notable demands for the introduction of a ‘race’ question or relabelling ‘mixed’ as ‘mixed race’ have been evident, and these changes are clearly not a priority for the ONS. Moreover, as the completion of the census is compulsory, the ONS seeks to avoid contested conceptualisation and categorisation that may not be acceptable to some members of the public and thereby put at risk the census operation as a whole. It is clear that ‘race’ is a contested term that is unacceptable to some in the wider society. There are voluntary as opposed to compulsory vehicles such as social surveys and innovation panels where new questions or major amendments can be tested, including omnibus surveys. Further, a robust measure of opinion regarding ‘race’, how it is understood and its acceptability, is needed in community sample surveys that are generalisable to the wider population.

Amongst other suggestions by scholars for the census, a call has been made for a question set on experiences of racism, in large-scale surveys or the 2031 Census (if, indeed, the latter has not been replaced by an administrative census), on the back of government-commissioned research that has questioned the role of structural racism. Similarly, in a US context and with a related objective,

López and Hogan (

2021) have called for the urgency of revising the US Census to include a separate question on street race (‘If you were walking down the street, what race do you think others who do not know you would automatically think you were, based on what you look like?’ (p. 18)). Given the concern of the census not to jeopardise overall response rates to the enumeration, even small changes are subjected to an exhaustive programme of cognitive research, focus group work, and small and large-scale tests. Petitions for large (and in some cases controversial) changes, while inserting one strand of information into the decision-making process, may find little traction.

4.1.4. The Capture of Racial Diversity in the ‘Mixed’ Category

The critique here is that the ‘ONS’s ‘measurement of “mixed” people…seriously compromises our …understanding of the racial diversity contained within the category “mixed”’ (

Song 2018, p. 1138). It is difficult to see how this suggested deficit in data capture would be changed if the conceptual base of the question in Britain was ‘race’. The current ‘mixed’ categorisation encompasses the main combinations identified by ‘mixed race’ people in the population as a whole (as revealed by the 1991 Census write-ins) and thereby achieves substantial coverage. However, like all five sections of the census, the predesignated tick options cannot cover all possible responses. In response to the increasing ethnic diversity of the population, the ONS introduced distributed free-text in the 2001 England and Wales Census, so that form-fillers could write in their own preferred identifiers. Given the ‘example effects’ of the three ‘exact combinations’, one might expect write-in respondents to be cued as to the kind of mixes the question was seeking. Indeed, these responses included ‘Black and Asian’ (

n = 6262), ‘Black and White’ (

n = 13,695), ‘Chinese and White’ (

n = 13,358), ‘White and Arab’ (

n = 9074) (important following the ONS’s addition in 2011 of ‘Arab’ to the ethnic group options), and ‘Latin/South/Central American’ (

n = 12,103). The lack of an ‘and’ in the latter description suggests mixing foundational to this region rather than reference to recent ancestry. While free-text responses are always an undercount of their ‘category’, they provide indicative evidence of the diversity of the ‘mixed’ population. Indeed, the ONS coded the ‘Mixed’ open responses in the 2011 Census into 71 categories, the largest number of categories derived from the write-ins across the five pan-ethnic sections, for which it provided counts at the local authority level.

Ethnic group classifications comprising tick box options have an upper limit of categories that can be included because of ‘respondent burden’. Across the five census sections, that for ‘Mixed/Multiple’ already has the second highest number of options. In time, as the ONS has acknowledged, the growing size of the ‘Any other mixed background’ category (already the largest ‘Mixed’ category in some local authorities) may require a review of how the mixed population is best measured. The ‘tick two or more’ approach, as used in the USA and Canada, would certainly yield a better measure of the ethnic and pan-ethnic diversity of this group, with five or more combinations being frequently reported in the USA, though current evidence indicates that it would encounter problems of data quality and respondent understandings.

4.1.5. Identity or Ancestral Origin

This final issue concerning the ‘mixed’ group has not arisen out of the challenge of ‘race’ to official categorisation by ethnic group but raises some issues that are relevant to this debate. It has been observed by researchers and social science research organisations in the UK and USA and reported in the UK national press. Some uncertainty has been expressed about whether people are self-identifying as ‘mixed’ (in an ethnic group question that invites the form-filler to choose an option ‘to best describe your ethnic group or background’) or are choosing ‘mixed’ by virtue of their parentage or recent ancestry (as might be asked in an ancestry question). Data on these two options were collected for all categories in the Fourth National Survey and showed reasonable equivalence across most predesignated categories except for ‘mixed’ (

Modood et al. 1997). A similar criticism has been made of the ‘two or more races’ population identified in the 2000 United States Census by

Harrison (

2002), who argues that data for the self-identified multiple-race populations may ‘not provide good proxies for those that might be obtained from defining these populations by parentage or ancestry’. He claims that the former does not represent ‘any meaningful population’, forgoing the Census Bureau’s view that its meaningfulness and coherence derive from the process of self-identification. There is no reason to conjecture that this ambiguity would be any different if the conceptual base of the question in Britain was ‘race’.

It is clear that the ONS is seeking to capture self-identification, though ancestry may be a factor that contributes to this. The underlying conceptual base of both the England and Wales and US Census questions is, respectively, ethnic and racial self-identification. The

Office for National Statistics (

2003) has explicitly argued that in the census, ‘categories should be used … that reflect people’s own preferred ethnic descriptions of themselves’. The US Census Bureau has also emphasised that the terms used to identify population groups should be familiar and acceptable to the people described ‘if the principle of self-identification is to be honored’ (

US Office of Management and Budget 1997). The wording of the England and Wales 2011 Census ethnic group question (retained for the 2021 Census) emphasises the subjectivity of the choice. It does not specify or attempt to influence the criteria the respondent should use in making that choice: in the words of the ONS: ‘It’s up to you how you answer this question. Your ethnic group could be your cultural or family background’. This seems to be preferable to the state laying down the criteria that should be used by respondents.

The point with self-identification questions is that the form-filler will draw upon their own perceptions and experiences in deciding how they answer the question. Many factors may potentially inform that decision. The saliency of a set of these partially drawn from the 1996 Current Population Survey Supplement on Race and Ethnicity was investigated in a survey questionnaire (

Aspinall and Song 2013) with respect to mixed race, albeit with respondents who primarily identified as ‘mixed race’: ‘It is my own sense of personal identity’; ‘It is the way society sees me’; ‘It is the group I feel I belong to’; ‘My parents are from different racial/ethnic groups’; ‘My ancestors (forebears) before my parents were from different racial/ethnic groups’; ‘My friends/peers identify me in this way’; and an open response ‘Some other reason’. A varying mix of multiple reasons was ticked.

The ONS has made it clear in the last four (1991–2021) census development programmes that the purpose of the ethnic group question is to seek respondents’ self-identifications rather than some other conceptual base such as racial/ethnic descent or ancestry. Even the 1991 Census left the choice for mixed respondents to ‘tick the group to which the person considers he/she belongs or …describe the person’s ancestry in the space provided’. Thus, when

Berthoud (

1998) proposed a question for the 2001 England and Wales Census asking about the respondent’s ‘family’s ethnic origins’ (‘your mother’s family’ and ‘your father’s family’), this was eschewed by the ONS on the grounds that the ethnic group question was designed to capture self-identity. Berthoud’s question was

operationally defined, constraining the respondent to report the ethnic group of their mother and father. To capture such a measure of mixedness would have required the ONS to abandon self-identification, the chosen concept since the first tests for a census ethnic group question in the mid-1970s, for one based on parentage. Attention has been drawn to the analytical distinction between these two conceptualisations by scholars and organisations.

Smith (

2002) has argued that self-elected ethnic group membership is different from assigned family origins which fits with Max Weber’s concept of a status group. The consequences of these different conceptualisations of self-ascribed ethnic group and family origin have, perhaps, nowhere been more explicitly stated (and accurately predicted) than by the Scottish Office (

Smith 1991): ‘…such different philosophical approaches to classification may lead not only to data being collected in very different ways, but to very different interpretations’.

These measures of identity and ancestral origin yield different populations, though with some limited overlap, attesting to the interpretation of ‘mixed’ as the form-filler’s own self-identification or interpretation. For example, in the Fourth National Survey (

Modood et al. 1997), of those who gave ‘Mixed’ family origins (unweighted

n = 488), only 40% identified as ‘Mixed’ in the group membership question, the former being 2.5 times larger. The UK Household Longitudinal Study data also indicate that operational definitions of mixedness based on parentage captured a substantially larger (by a multiple of over 3) ‘mixed’ population (

McFall 2012), the majority of persons who have mixed parentage identifying with a single group. Similar findings have been found in US data, with the

Pew Research Center (

2015) reporting in its 2015 survey that only four in ten adults with a mixed racial background (39 percent) said they considered themselves to be ‘mixed race or multiracial’. As in Britain, the US Census Bureau opted for self-identification rather than ancestry for capturing data and hence the two or more races population. For some particular types of research, for example, the assessment of health risks, it may be advantageous to collect data in social surveys using both approaches, but the decennial census has consistently privileged self-identification rather than seeking to constrain or regulate respondents’ answers.

4.2. The Challenge of Interracial Unions

A further challenge to the UK’s official categorisation by ethnic group has come from Song’s argument that inter-ethnic rather than interracial unions are derived from these data, and that this makes the assumption of equivalence. Yet, the ONS’s coverage of these data, in fact, encompasses both inter-ethnic and interracial unions, rather than disregarding the distinction between them.

The ONS’s tabulation of inter-ethnic unions is derived using data from the household question (how members of the household are related to each other) and the ethnic group question. The range of ONS outputs on inter-ethnic and pan-ethnic unions reflects the varying needs of census data users, including those who require special tabulations (so-called commissioned tables). The ONS’s primary purpose is to produce official statistics for policy makers in central and local government, so the first statistics released are generally key statistics. Early on in the process, the table commissioning process is initiated. It is perhaps no surprise (given the ethnic diversity of the capital city) that the full inter-ethnic union data from the 1991 and 2001 England and Wales Censuses were first derived through tables commissioned by the Greater London Authority (GLA) (respectively, tables LRCT60 and C0007). Access to these tables was simultaneously provided for all data users. In these matrices of unions, the ethnicity of the partners uses the full set of 1991 or 2001 ethnic group options to yield the maximum information content for policy purposes. Such matrices could only be termed ‘inter-ethnic’. In a similar way,

Statistics Canada’s (

2014) release on mixed unions is for the full set of population group (visible minorities) categories, where the unions include mixes of ‘Japanese’ and ‘Korean’, for example. In terms of its data releases or reports from the 2001 and 2011 Censuses, the ONS is attentive to unions at

both the granular and pan-ethnic or ‘broad ethnic group’ (racial) levels.

In a general policy context (which may include, for example, integration policies), tables of unions between, say, the ‘White British’ and ‘Any other White background’ groups, the largest combination for the ‘Other White’ group, are clearly of importance, as are, of course, those unions across the pan-ethnicities, such as ‘White British’ and ‘Indian’ or ‘White’ and ‘Asian’. A total of 86% in the ‘Other White’ group were born abroad (the highest of any ethnic group), and 78% in this group wrote in a foreign identity only in the 2011 Census National Identity question, substantially the largest of any of the 18 ethnic categories. Moreover, only 35.9% in the ‘other White’ group had English as their main language, the lowest of any ethnic category and substantially lower than any of the four ‘Asian/Asian British’ groups. The requirement for early release of the full dataset is evident.

4.2.1. The Provision of Inter-Ethnic and Pan-Ethnic Unions

Given the interest in ‘interracial’ unions, the ONS might have been judged remiss had it provided data or commentary

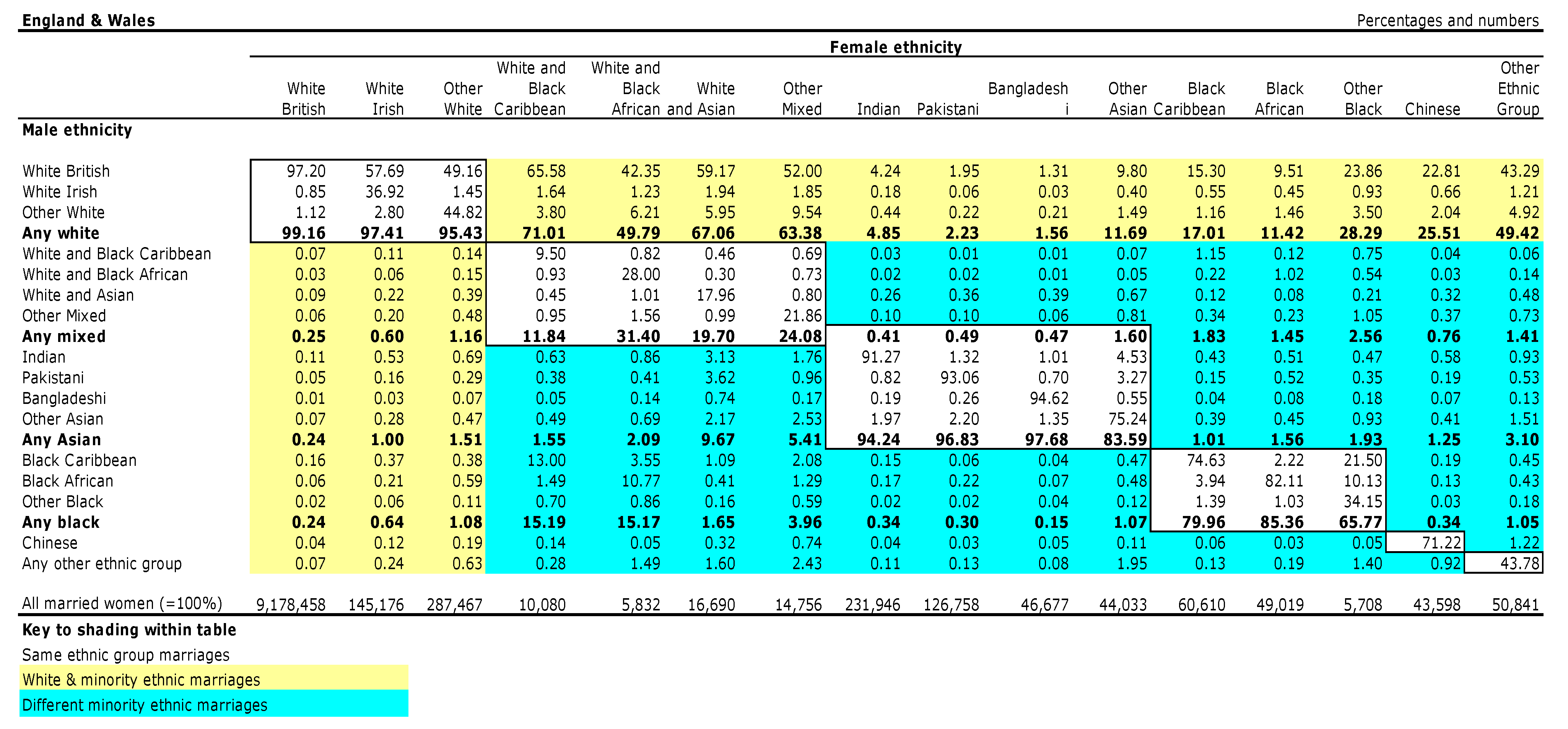

only for the full ethnic group matrix, though counts and proportions of pan-ethnic (‘broad ethnic group’) or interracial unions (‘pan-ethnic’ as opposed to ‘racial’ is sometimes used in the US sociological literature referencing interracial unions) can be derived through aggregation from the full tabulations. However, the ONS has published data for interracial (across pan-ethnicities) unions for both the 2001 and 2011 Censuses. In 2005, the ONS provided commentary on data from the England and Wales 2001 Census on inter-ethnic marriages (

Office for National Statistics 2005), defined as marriages between ‘people from different aggregate ethnic groups, where the ethnic group categories were: White, Mixed, Asian, Black, Chinese, and Other ethnic group’, as well as at the more granular level. Thus defined, 2% of marriages were between people from different pan-ethnic backgrounds. The two linked reference tables provide data for the percentage of women married to men, and percentage of men married to women, by detailed ethnic group, the ethnicity for the male and female partners being provided at both the pan-ethnic and detailed levels. Column totals of the numbers enable all combinations to be calculated. The tables (see

Figure 1) shade the matrices according to same ethnic group marriages (e.g., White British and Other White, or Other Black and Black African), white and minority ethnic group marriages, and different minority ethnic group marriages, so the exact constituencies of these three groupings are explicit. With respect to the full ONS 2001 Census 16-fold classification (in addition to the above data on marriages), data for inter-ethnic unions (couples who are both married

and cohabiting) are hosted on the ONS’s website (

Office for National Statistics 2014a) and an analysis provided by

Mackintosh (

2005) based on the Greater London Authority’s commissioned table.

The ONS’s analytical report on inter-ethnic unions based on data for the 2011 England and Wales Census focused on the full 18 granular categories (

Office for National Statistics 2014c). However, data releases included

both those in inter-ethnic unions across the full matrix of 18 granular ethnic group tick boxes

and across the five broad ethnic group sections or pan-ethnicities (White, Mixed, Asian, Black, and Other) (

Office for National Statistics 2014b). These data are tabulated for all partnerships, marriages and civil partnerships, and cohabiting couples by ethnic group, and by age band for females and males. Thus, counts and proportions in inter-ethnic relationships can be explored between, say, any permutations of the 18 categories, such as ‘White Irish’ and ‘Any Other White Background’ and ‘Indian’ and ‘Chinese’

or where the partners are, say, ‘White’ and ‘Asian’ or ‘Asian’ and ‘Black’, or, indeed, any permutation of the five pan-ethnicities. Thus, data users can read off from these presentations all the problematic combinations identified by

Song (

2015,

2018): ‘unions without wholly white partners’, ‘those involving people seen as belonging to visibly different “races”’, ‘an inter-ethnic relationship between groups within the broad ethnic group categories’, and unions between non-white people at the granular level.

The availability of ONS data to enable the analysis of inter-ethnic unions at either the granular or pan-ethnic level, or, indeed, researcher-defined aggregates, offers maximum flexibility, with no deficits in terms of data availability. Should a researcher, for example, wish to derive their own typologies of ‘mixed’ unions, all the data are available to do so (for useful discussions of co-ethnic and inter-ethnic unions, see (

Platt 2010), pp. 13–14, and those with/without ‘racial overlap’, (

Song 2015), pp. 98–100). In terms of the descriptive analysis at the granular level for the 2011 Census (notably, patterns of inter-ethnic relationships and differences between men and women; across age groups; and across relationship types), this can be directly replicated using the tabular data for unions at the pan-ethnic level.

Indeed, the data at the pan-ethnicity (broad ethnic group) level are similar to those of the US Census Bureau for the ‘two or more races’ population, with respect to aggregation, that is, tabulated across broadly defined racial groups: White; Black or African American; Asian; American Indian and Alaska Native; Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander; and Some Other Race. Researchers who may wish to investigate interracial unions in the USA at a finer granularity, such as Chinese and Samoan, are able to exploit the Public Use Microdata Samples. The salient perspective in the British context is that both types of presentation of inter-ethnic unions across the full 18 groups and for the five interracial (pan-ethnic) categories are useful and maximise the utility of the data.

4.2.2. The Analytical Value of Inter-Ethnic vs. Interracial Unions

The ONS justifies a focus on the granular categories in its 2014 analytical report on the grounds that: ‘The pattern of inter-ethnic relationships is far better understood using all 18 ethnic group classifications-this shows inter-ethnic relationships and the differences between and within the subcategories of the main ethnic groups, thus offering insights into changes in society. Numbers in the census also make analysis at the lower level possible and thus such detail adds more value’. If we focus on, say, the ethnicity of the partners of Asian females, the granular ethnicity data reveal that in 2011, 12.2% of Indian, 7.7% of Pakistani, and 6.8% of Bangladeshi females were in inter-ethnic unions (that is, unions outside their own specific ethnic background). This compares with 39.5% of Chinese and 38.4% of Other Asian females. Cultural, ethnic, and religious differences underpinned this wide range. When these five Asian categories are lumped together in an ‘Asian’ pan-ethnicity, we find that 14.9% of Asian females were in an ‘interracial’ relationship (that is, outside the ‘Asian’ collectivity). For that reason,

Feng et al. (

2010) chose to split the ‘Asian’ group into ‘South Asian’ and ‘Other Asian’ in their analyses of inter-ethnic unions using the ONS Longitudinal Study (LS). Similarly, with respect to the ‘Black’ pan-ethnicity, there were more than threefold differences in the prevalence of inter-ethnic unions for females who were Black Africans (18.6%) and Other Black (59.3%), with Black Caribbeans intermediate (36.6%), with the proportion for the ‘Black’ group as a whole (21.2%) revealing none of this variation. These meaningless statistical abstractions do not reflect any of the ethnic groups they encompass and invoke ‘the fallacy of homogeneity’ (or ‘the fallacy of monolithic identity’) (

Stanfield and Dennis 1993, p. 23;

Bhopal 2002, p. 242), that is, the misinterpretation of population data from heterogeneous populations, and lack explanatory value given the level of abstraction. Where analysis at the granular ethnicity level systematically correlates with different outcomes (in this case the prevalence of inter-ethnic unions), a requirement for data analytics to capture this is created.

This is perhaps why analysts of inter-ethnic unions using other data sources chose granular ethnic groups where sample sizes allowed: for example,

Berthoud and Beishon (

1997) (Fourth National Survey of Ethnic Minorities, 5 categories: Caribbean, Chinese, Indians and African Asians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis);

Muttarak (

2004) and

Platt (

2010) (pooled Labour Force Survey data, varying from 11 to 13 categories); and

Kulu and Hannemann (

2019) (Understanding Society, First Wave 2009–10, 5 categories: Europe and other Western/industrialised countries, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, Caribbean countries, and all other origins, with small sample sizes requiring some aggregation).

The ONS further justifies a focus on the granular categories in that: ‘Differences in the ethnic group tick-box classifications between the years have affected comparability with some groups. Therefore the detailed ethnic group categories should be used’. The constituency of the pan-ethnicities has changed from census to census, making interpretations of ‘interracial’ union patterns over time problematic: in 2001, the Chinese category was located in the final ‘Other’ section and moved to the ‘Asian/Asian British’ section in the 2011 Census, thus also influencing capture in the ‘Any other Asian background’ option. In 2011, a new ‘Arab’ category was located in the final ‘Other’ section, with counts for this group having been distributed across write-in categories in the 2001 Census.

4.2.3. The Utilities and Disutilities of the Two Conceptualisations

There are clearly a number of utilities and disutilities in highlighting ‘interracial unions’ separately from the full granular matrix. The ONS’s provision of data on unions across the pan-ethnicities may facilitate cross-national comparisons with countries such as the USA and Canada, though the constituency of the ‘White’, ‘Black’, and ‘Asian’ collectivities in the USA, Canada, and UK populations differs significantly in terms of national origins, migrant status, and experiences of racialisation. When such work has been undertaken, comparable categorisations of inter-ethnic unions have been derived from the ONS Samples of Anonymised Records (SARs), as in

Model and Fisher’s (

2002) comparison of Black and White interracial marriages in England and the USA. Aggregation at the pan-ethnic level may facilitate comparison across datasets where the granular categories differ. However, making interracial unions conspicuous in tabulations has its downside. Commenting on the US Census Bureau’s acknowledgement of ‘the stunningly high rates of intermarriage among those ethnic groups not designated as racial groups’,

Perlmann and Waters (

2002) argued: ‘If we mean to break down racial barriers, we have an interest in seeing to it that racial intermarriage is treated in the same matter-of-fact way that any other form of ethnic intermarriage is treated’.

In summary, the ONS’s decision to label the ‘mixed race’ group as ‘mixed’ (or ‘mixed/multiple’) with respect to ethnic background and the way inter-ethnic unions are tabulated and reported by the ONS do not offer the grounds for a sustainable challenge to the conceptualisation of ethnic group in the England and Wales decennial census and wider government. While the USA utilises the concept of ‘race’ (to include racial and national origin or socio-cultural groups) in its decennial census and reports its multiple race population in counts of the ‘two or more races’ population, different processes of ethnogenesis in Britain have given rise to a different conceptual basis and terminology. The ONS has indicated that ‘race’ would be less acceptable than ethnic group to the wider population, and that ethnic group is now the term of choice in nearly all official data. Indeed, there has been no use of ‘race’ (or derivatives of ‘racial’) in the decennial population census since 1991. Broad ethnic groups (pan-ethnicities) are already used in reporting inter-ethnic unions, and renaming these aggregates as ‘racial’ seems a pointless semantic exercise when the question’s conceptual base is ethnic group and background. It is to 1 of the 18 ethnic group or background categories which respondents self-assign their ethnic identity, and the question makes no reference to ‘race’. It would seem insensitive to co-opt respondents’ choices for use in derivative tabulations under the banner of a different conceptual base. The five pan-ethnic section headings have some utility analytically (for example, in harmonising data across different contexts), though there is little evidence that respondents readily self-identify with these broad labels, either in response to external racialisation processes or as participants in pan-ethnic boundary making. For example,

Modood et al. (

1994, p. 91) noted: ‘Most South Asians…identified more with an ethnic or religious identity than with being “Asians”’, a view supported by free-text responses in survey data (

Aspinall 2012).

Even in the USA, there has been much equivocation on the use of ‘race’ in the census.

Prewitt (

2013, p. 176), director of the US Census Bureau during 1998–2001, argued that ‘the census race question is not based on a coherent definition of race, and that it mixes categories based on colour with categories based on ancestry or national origin’. The

American Anthropological Association (

1997) has recommended that the term ‘ethnicity’ replace ‘race’ in federal classifications.

Morning (

2008, p. 260) has suggested that ‘one unintended effect’ of treating ‘race’ and ethnicity as different types of identity ‘may be to reinforce essentialist biological understandings of

race’. She argues a case for removing the term ‘race’ from the question to underline the socially constructed nature of the categories and to ‘bring the United States’ practice closer to that of other nations’.

Braveman and Parker Dominguez (

2021) make a similar point: ‘The continued distinction between “race” and “ethnicity” only serves to underscore the implication that “race” reflects biological differences’. In the 2020 US Census, the position of ‘race’ has become even more questionable given that the listed ‘races’ are now section headings for ‘origins’ write-in fields and the final ‘Some other race’ option invites a response of ‘print race or origin’.

4.3. ‘Race’ and Understandings of Racism

The suggestion that the use of ‘race’ as opposed to ethnic group would have greater efficacy in our understanding of racism is

Song’s (

2018) final challenge to current practice: ‘The concept of race is central to an understanding of racism which involves both structures of inequality and various modes of domination; as such, we still very much need “race”’ (p. 1142). Conversely, use of a ‘self-defined measure of “ethnic group” can be at odds with the aim of capturing information about ethnic and racial diversity, not to mention information about racial (in)equalities and opportunities’ (p. 1138).

Data for both broad (pan-ethnic) and granular categories are available from two England and Wales censuses (and imminent for the 2021 Census). The data that are collected by the ONS using the census ethnic group classification have many uses, including to set out and monitor ethnic inequalities in health, housing markets, the labour market, educational attainment, and quality of the living environment and, in addition, to track neighbourhood ethnic residential segregation (

Jivraj and Simpson 2015). Another widespread usage is to assess ethnic diversity in a wide range of settings such as workplaces and to investigate whether those who deliver services are representative of the populations they serve. Moreover, over the last decade or so, substantial literature has been published on ‘ethnic density’ or ‘group density’ effects (

Bécares 2009) which can moderate the impacts of racism. Including all those organisations and individuals who use the census ethnic group classifications to measure ethnic disparities and for other purposes, the evidence base is now voluminous.

Clearly, utilising data classified by ethnic group to explore disparities raises issues of quality. For example, many of these datasets are hosted on the Race Disparity Audit’s ‘Ethnicity facts and figures’ website under nine topic areas (education, skills, and training, health, housing, etc.). Given the focus of the Special Issue, let us take the example of the ‘Mixed’ group. Of the 513 different dimensions encompassed by these ‘topic areas’, 15.0% had no mixed categorisation, 4.7% used ‘other including mixed’, 52.6% used ‘mixed’, and 27.7% used the detailed (four granular) ‘mixed’ tick boxes. For this huge body of data on disparities, then, ‘Mixed’ was excluded from the categorisation altogether or concealed in an ‘other including mixed’ category in a fifth of the dimensions. Only just over a quarter used the full census ‘Mixed’ categorisation, as recommended by the ONS.

It is likely that structural racism and disadvantage have played a part in producing inequalities in all these areas, yet it is clear that there are some important deficits with respect to the measurement of the ‘mixed’ group in these reported disparities, especially the loss of detail by the use of the aggregate (pan-ethnic) ‘mixed’ group. Moreover, it is known from record linkage studies that there are high levels of inconsistency in the responses of the same individuals, both across decennial censuses (

Simpson et al. 2014) and between different (but contemporaneous) data sources (

Saunders et al. 2013). These measurement issues are rightly accorded attention. However, the census data user community has not identified the use of a conceptual base of ‘race’ amongst them.

Song’s (

2018, p. 1140) specific challenge is that ‘If the stated purpose of the British census ethnicity question… is to best discern the population’s ethnic characteristics to engage in forms of equal opportunity monitoring, the collection of ethnic data in the form of self-identification (using the “ethnic” categories in the 2011 census) does not provide the most useful (or necessary) information’. This takes us to the several different conceptualisations of descent communities now in play that are potentially available for disparity and equal opportunity measurement. In a US context,

Roth (

2016) distinguished between how people identify themselves (‘racial identity’) and what they check on official forms or surveys with limited options (‘racial self-classification’).

Prewitt (

2013) termed the responses to the latter ‘statistical races’. The ONS also recognises the way in which official classifications of ethnic group set limits to the capture of ethnic group identity (

Office for National Statistics 2003). Unprompted free-text, standing alone, has very occasionally been used in surveys in the UK but lacks utility in a census context because of the challenges of coding the responses (‘administrative burden’), although free-text options are routinely part of the categorisation used in ethnicity questions. Further, while these two measures, racial identity and racial self-classification, may be conceptually distinct, they are less so as analytic measures, given the extensive public testing of categories in census development programmes and the trajectory of a rising number of tick box options.

Croll and Gerteis (

2019) explored the relationship between open-field identification, unconstrained by conventional fixed categories, and fixed-choice racial and ethnic identification in the same group of respondents and data collection exercise. They found that most of their respondents reproduced normative, categorical racial and ethnic descriptors to identify themselves.

Another set of like-terms comprises ‘reflected appraisals’ (

Khanna 2004), ‘reflected race’ (

Roth 2016), ‘street race’ or how individuals believe they are perceived by others (

López and Hogan 2021), and ‘socially mediated appearance’ (

Campbell and Troyer 2007). These terms cannot be construed as proxy measures for ‘socially assigned race’ (

Jones et al. 2008), or what Roth calls ‘observed race’, as they are self- or internally assigned. However, they are of interest in their own right as a strong ethnic identity that is not misunderstood may be protective against the effects of racism.

‘Socially assigned race’, how people are actually seen by others in racial and ethnic terms, is impractical to capture at a population level or in routine official data collection settings. It would raise issues of finding observers; complying with data collection protocols that privilege self-assignment; observing data protection, sharing of data, and data privacy regulations; and assuaging ethical concerns. Further, observer assignment is known to be related to the observers’ own racial identifications, such that ‘we cannot be sure any two randomly selected observers would perceive a respondent in the same way’ (

Campbell and Troyer 2007, p. 754). Observer assignment was last used in an official context in Britain in the 1980s, being abandoned in the General Household Survey and British Crime Survey in 1986 and 1988, respectively. Only a few research studies now use this method to obtain the wider society’s perception of a person’s race or ethnicity, or the way ethnicity is constructed in everyday social interactions. Recent US studies using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) survey have documented high levels of misclassification (

Campbell and Troyer 2007).

Which particular concept, level of granularity, or method of assignment is optimal in this context of inequality measurement is poorly explored in the literature. A few studies indicate the efficacy of ‘socially perceived ethnicity’. For example,

Jones et al. (

2008) investigated variations in self-reported health according to whether it was examined in relation to the ‘race’ that other people generally assumed the survey respondents to be or the respondents’ self-identified ‘race’ and found the former to be more significant. A recent scoping review of 20 studies (

White et al. 2020) mainly found an association between ‘socially assigned race’ and health. Clearly, the impracticality of this approach when the UK’s official data collection by ethnic group is population-based, as in the census, many surveys, and some service settings, rules it out.

Further, arguing for minimal change retaining self-assignment but simply changing the label from ‘ethnic group’ to ‘race’ seems both pointless and potentially injudicious, given some overlap of the terminology in this country and the possibility that dislike of the term ‘race’ would evoke non-response. Indeed,

Braveman and Parker Dominguez (

2021) argue that the use of the term ‘race’ is an obstacle in the study of racism, ‘one that amplifies the damage every time it is used’: ‘Abandoning “race” should … remove one ubiquitous and not inconsequential source of constant reinforcement of racism’ as ‘it is irremediably imbued with scientifically unfounded but nevertheless tenacious notions of biological differences and hierarchy which have long served to justify exploitation and oppression’. While self-assigned ethnic group and self-assigned ‘race’ cannot be assumed to be meaningful proxies for how individuals are perceived by others, both are salient in the measurement of inequalities and disparities in the UK and USA, respectively.

In official UK contexts, such as the census and large-scale government social and general-purpose surveys, current categorisations and classifications for ethnic group have merit, not least because they have undergone extensive testing with regard to understanding by, and acceptability to, the public and also meet the technical standards required for such data collections. As the experience of the 2006 Scottish Census Test (resulting in misinterpretation of the categorisation) and some trials of stand-alone open response (invoking high non-response rates) have showed, such standards are not always met. Census data are regarded by the UK Statistics Authority as ‘official statistics’ (‘that… meet the highest standards of trustworthiness, quality and value’) rather than ‘experimental statistics’ (‘newly developed or innovative statistics’). That requirement would be compromised by the adoption of what

Song (

2018, p. 1131) terms ‘this very troublesome concept’ of ‘race’, burdened as it is with ambiguity and malleability, a fraught past, a continuing belief by many that it is a biological category, and evidence of a lack of its acceptability in the wider society.