Shape Shifting: Toward a Theory of Racial Change

Abstract

:1. Some Preliminary Considerations

- Ancestry. A single ancestor will be enough to make one eligible for membership.

- Family. Is there a group of people who are indisputably members of the group to which you say you belong that recognizes you as a member of the group?

- Cultural practice. Does one behave as one is expected to behave in this group?

- Place. Is there a place from which you spring that is deeply associated with the group in which you are claiming identity?

2. Conditions That Abet Shape Shifting

- War (the violent clashing of two or more peoples, in very uncertain circumstances for individuals, sometimes leading to individuals making unexpected identity choices);

- Slavery (in the modern world, often the enslavement of one kind of people by another);

- Migration (people from one part of the world going to another place and trying to find a way to become part of that other society);

- Empire (the bringing together of disparate peoples into a single social field);

- Nation building (when governments often try to impose a single identity on a variety of peoples); and

- Borderlands (at the fringes where two or more societies touch, intersect, and overlap, providing room for individuals, even whole groups, to move back and forth).

3. Changing Context, Changing Identity

Ni shi Nippon-ren—“So you’re Japanese”, he declared.Bu shi. Wo shi Mei-guo-ren—“No, I’m American”, I answered.Na shi shenme?—“What’s that?” he asked. And then it occurred to me: aside from the loudspeaker playing Radio Beijing overhead (in Chinese), there was no local means of learning about the outside world. No Uyghur language radio, no television, no newspaper. Few outside visitors except for Chinese bureaucrats. No way of knowing about the United States, or much else outside Turpan.

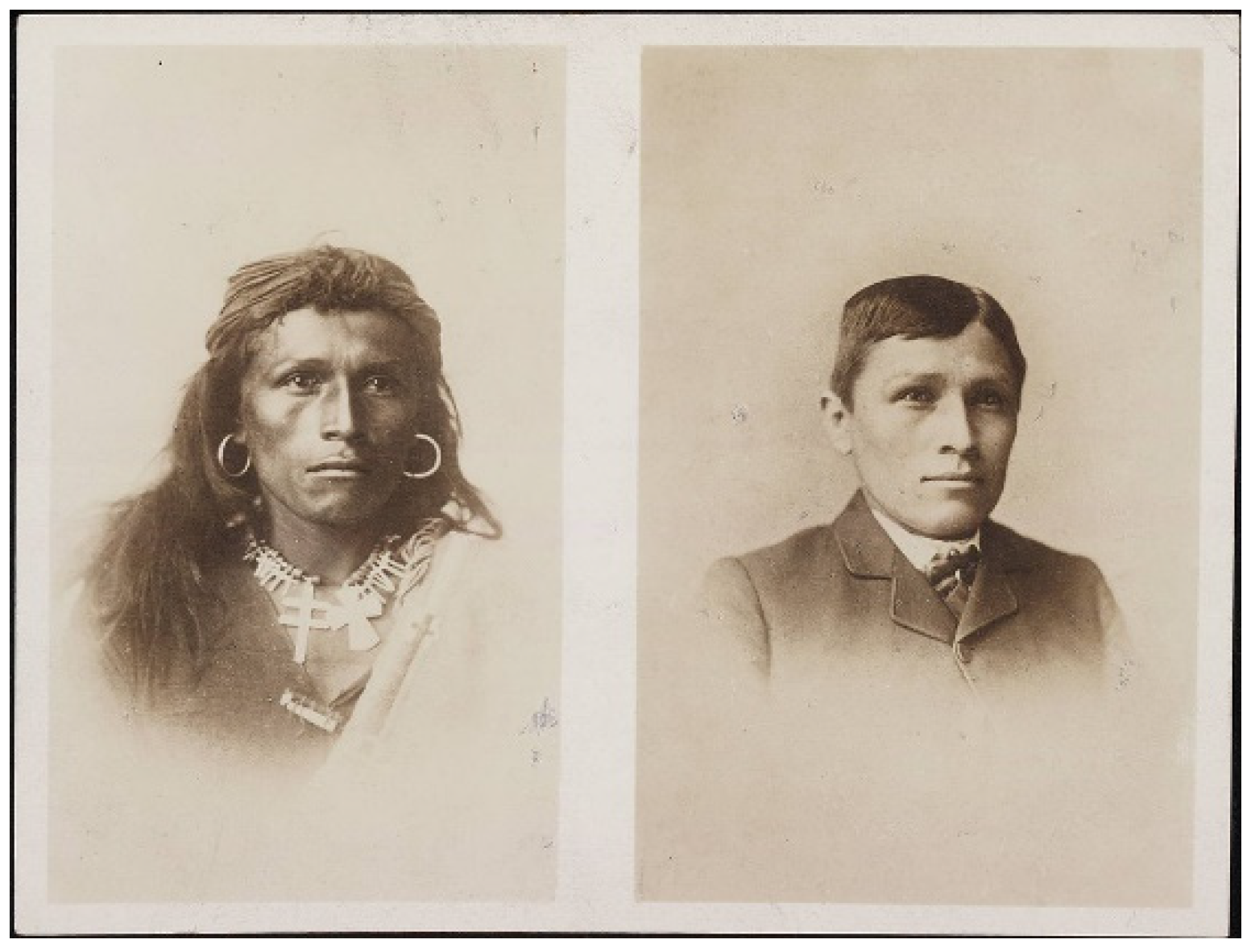

4. Compelled Identity Change

5. Racial Change by Choice

Smith wants to respect Korla Pandit for the brave, ingenious thing he achieved in becoming, and remaining, Korla Pandit. I am not unsympathetic to his emotion.To consider the life of Korla Pandit—and that’s what I will call him because that is who he became—is to consider the weight of wearing a mask for 50 years. It is to grasp the fear of exposure, of a revelation that would have killed his career. One slip and he would have gone from being a mirror of white America’s mania for things “exotic” to somebody white American didn’t want to face. … It is to recognize how he had to cut himself off from a black community that he’d grown up in, from a culture that had shaped the musical skills, and the survival skills, that he drew on for the rest of his life.

6. A Complex Case

7. Reflection

- Sometimes individuals or groups change their racial positioning because their context changes; either they move from one racial system to another, or their own racial system revises its rules. Almost no one ever questions the authenticity of such a change. It’s just what happens.

- Often people or groups are compelled by forces beyond their control, whether institutional or personal. Here again, authenticity is not the issue.

- Sometimes people and groups make choices that lead them to choose to change their racial or other primary identity within a stable social situation—to pursue an opportunity, for love, out of political commitment, or for other reasons. It is only in these few instances that we onlookers are tempted to judge their authenticity.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | For relatively recent incantations of pseudoscientific racism, see: Herrnstein and Murray (1996) and Wade (2014). |

| 4 | I will also not be talking about changes of gender identity. That is an important and not entirely unrelated topic, but this is just one short article and I am already taking on a lot of territory. |

| 5 | |

| 6 | It should be noted that the Rus’ of Novgorod had a similar conversion experience near the end of the tenth century at the direction of Vladimir the Great. According to tradition, in order to strengthen the solidarity of his growing kingdom the Prince sought a modern (for those times) religion to replace various pagan traditions. He auditioned Catholic, Orthodox, Muslim, and Jewish (from Khazaria) divines and ended up choosing Orthodoxy. Of course it surely was a much longer transition than that stereotypical summary, and it involved a lot of other actors, but nonetheless it was conversion from above (Spinka 1926; Ericsson 1966). At various times there were other Jewish kingdoms in the modern territories of Yemen, Ethiopia, and elsewhere, of which some remnants remain (Maroney 2010; Goitein 1973; Quirin 2010; Kessler 1996). |

| 7 | K. Tsianina Lomawaima and others make the point that not everything that happened at these schools was bad, and that many former students have good memories of their time there (Lomawaima et al. 2000; Lomawaima and McCarty 2006). For analogous attempts at forcing racial change on Indigenous youth in Canada, see, e.g.,: Milloy and McCallum (2017); Grimes (2022); Regan (2011). |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | Some even claimed other identities for her: Korean, half-Russian, Taiwanese. She was indeed a shape shifter. Shelley Stephenson (2002) is particularly acute on this matter: “Li Xianglan was, it seems, many things to many people, and more often than not she was somehow ‘theirs’”. |

| 11 | Japanese audiences learned her name as Ri Koran. |

References

- Adams, David Wallace. 2020. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928, 2nd ed. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. [Google Scholar]

- Amnesty International. 2021. “Like We Were Enemies in a War”: China’s Mass Internment, Torture and Persecution of Muslims in Xinjiang. London: Amnesty International. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, rev. ed. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, John A. 1982. Nations Before Nationalism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Banton, Michael. 1987. Racial Theories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, Fredrik, ed. 1969. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries. London: Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Baskett, Michael. 2008. The Attractive Empire: Transnational Film Culture in Imperial Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Behar, Doron M., Mark G. Thomas, Karl Skorecki, Michael F. Hammer, Ekaterina Bulygina, Dror Rosengarten, Abigail L. Jones, Karen Held, Vivian Moses, David Goldstein, and et al. 2003. Multiple Origins of Ashkenazi Levites: Y Chromosome Evidence for Both Near Eastern and European Ancestries. American Journal of Human Genetics 73: 768–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bell, Philip. 2002. Subjectivity and Identity: Semiotics as Psychological Explanation. Social Semiotics 12: 201–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Brit. 2020. The Vanishing Half. New York: Riverhead. [Google Scholar]

- Bjornsdottir, Inga Dora. 2010. Ólöf the Eskimo Lady: A Biography of an Icelandic Dwarf in America. Translated by Maria Helga Gudmundsdottir. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenbach, Johann Friedrich. 1969. On the Natural Varieties of Mankind. Translated and Edited by Thomas Bendyshe. New York: Bergman, German original 1775. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld, Warren J., Khyati Y. Joshi, and Ellen E. Fairchild, eds. 2008. Investigating Christian Privilege and Religious Oppression in the United States. Rotterdam: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Boas, Franz. 1940. Race, Language, and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bovingdon, Gardner. 2010. The Uyghurs: Strangers in Their Own Land. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, Kevin Alan. 2006. The Jews of Khazaria, 2nd ed. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Browder, Laura. 2000. Slippery Characters: Ethnic Impersonators and American Identities. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Broyard, Anatole. 1997. Kafka Was the Rage: A Greenwich Village Memoir. New York: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Broyard, Bliss. 2007. One Drop: My Father’s Hidden Life—A Story of Race and Family Secrets. New York: Back Bay Books. [Google Scholar]

- Chesnutt, Charles W. 1900. The House Behind the Cedars. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Child, Brenda J. 2000. Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900–1940. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Choy, Catherine Ceniza. 2013. Global Families: A History of Asian International Adoption in America. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, Ward. 2004. Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools. San Francisco: City Lights Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell, Stephen, and Douglass Hartmann. 2006. Ethnicity and Race: Making Identities in a Changing World, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deaux, Kay. 2018. Ethnic/Racial Identity: Fuzzy Categories and Shifting Positions. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 677: 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delatolla, Andrew, and Joanne Yao. 2018. Racializing Religions: Constructing Colonial Identities in the Syrian Provinces in the Nineteenth Century. International Studies Review 21: 640–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demos, John. 1994. The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America. New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- di Leonardo, Micaela. 1984. The Varieties of Ethnic Experience: Kinship, Class, and Gender among California Italian-Americans. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dineen-Wimberly, Ingrid. 2019. The Allure of Blackness in Mixed-Race America. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. 1940. Dusk of Dawn: An Essay toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept. New York: Harcourt, Brace. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. 1968. The Autobiography of W. E. B. Du Bois. New York: International Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop, Douglas Morton. 1954. History of the Jewish Khazars. New York: Schocken. [Google Scholar]

- Duus, Masayo. 2004. The Life of Isamu Noguchi: Journey Without Borders. Translated by Peter Duus. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duus, Peter, Ramon H. Myers, and Mark R. Peattie, eds. 1983. The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895–1945. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duus, Peter, Ramon H. Myers, and Mark R. Peattie, eds. 1988. The Japanese Informal Empire, 1895–1937. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duus, Peter, Ramon H. Myers, and Mark R. Peattie, eds. 2010. The Japanese Wartime Empire, 1931–1945. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Egorova, Yulia. 2011. From Dalits to Bene Ephraim: Judaism in Andhra Pradesh. Religions of South Asia 4: 105–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorova, Yulia. 2015. Redefining the Converted Jewish Self: Race, Religion, and Israel’s Bena Menashe. American Anthropologist 177: 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Egorova, Yulia. 2018. Jews and Muslims in South Asia. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Egorova, Yulia, and Shahid Perwez. 2010. The Children of Ephraim: Being Jewish in Andhra Pradesh. Anthropology Today 26: 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorova, Yulia, and Shahid Perwez. 2013. The Jews of Andhra Pradesh: Contesting Caste and Religion in South India. New York: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Eley, Geoff, and Ronald Grigor Suny, eds. 1996. Becoming National. New York: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson, K. 1966. The Earliest Conversion of the Rus’ to Christianity. Slavonic and East European Review 44: 98–121. [Google Scholar]

- Fanshel, David. 1972. Far from the Reservation: The Transracial Adoption of American Indian Children. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fear-Segal, Jacqueline. 2007. White Man’s Club: Schools, Race, and the Struggle of Indian Acculturation. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fear-Segal, Jacqueline, and Susan D. Rose, eds. 2016. Carlisle Indian Industrial School: Indigenous Histories, Memories, and Reclamations. Lincoln: University Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gabaccia, Donna R. 2000. Italy’s Many Diasporas. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. 1997. The Passing of Anatole Broyard. In Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man. New York: Random House, pp. 180–214. [Google Scholar]

- Gaul, Theresa Strouth, ed. 2005. To Marry an Indian: The Marriage of Harriett Gold and Elias Boudinot in Letters, 1823–1839. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geary, Patrick J. 2002. The Myth of Nations: The Medieval Origins of Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gellner, Ernest. 1983. Nations and Nationalism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gobineau, Joseph-Arthur Comte de. 1915. Essay on the Inequality of Human Races. Translated by Adrian Collins. New York: Putnam’s, Original French, 1855. [Google Scholar]

- Goitein, S. D. 1973. From the Land of Sheba: Tales of the Jews of Yemen. New York: Schocken. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, Norman. 1982. Khazarian Hebrew Documents of the Tenth Century. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, Peter B. 2003. Nomads and Their Neighbors in the Russian Steppe. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, Peter B. 2010. Turks and Khazars: Origins, Institutions, and Interactions in Pre-Mongol Eurasia. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, Michael A. 1998. Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, Stephen Jay. 1996. The Mismeasure of Man, rev. ed. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, Darren. 2022. In Their Own Words: Testimony From the Students of Canada’s Indigenous Residential school Program. Chestermere: Adultbrain. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmo, Jennifer, and Salvatore Salerno, eds. 2003. Are Italians White? How Race is Made in America. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Haskins, James. 1973. Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Haskins, James. 1996. The First Black Governor: Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback. Trenton: Africa World Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein, Richard J., and Charles Murray. 1996. The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, Allyson. 2014. A Chosen Exile: A History of Passing in American Life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hobsbawm, E. J. 1990. Nations and Nationalism since 1780, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger, eds. 1983. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Högbacka, Ritta. 2016. The Dekinning of First Mothers: Global Families, Inequality and Transnational Adoption. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, Angela Pulley. 2015. Real Native Genius: How an Ex-Slave and a White Mormon Became Famous Indians. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, Fannie. 1933. Imitation of Life. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Margaret D. 2011. White Mother to a Dark Race: Settler Colonialism, Maternalism, and the Removal of Indigenous Children in the American West and Australia. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Margaret D. 2014. A Generation Removed: The Fostering and Adoption of Indigenous Children in the Postwar World. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, Karl. 2016. The Strange Career of William Ellis: The Texas Slave Who Became a Mexican Millionaire. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, Khyati Y. 2020. White Christian Privilege. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, David. 1996. The Falashas: A Short History of the Ethiopian Jews, 3rd ed. London: Frank Cass. [Google Scholar]

- Kevles, Daniel J. 1985. In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity. New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Eleana J. 2010. Adopted Territory: Transnational Korean Adoptees and the Politics of Belonging. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kleeman, Faye Yuan. 2014. In Transit: The Formation of the Colonial East Asian Cultural Sphere. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koestler, Arthur. 1976. The Thirteenth Tribe: The Khazar Empire and Its Heritage. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Korla (documentary film). 2015. Dir. John Turner. Written by Eric Christensen and John Turner. [Google Scholar]

- Languth, A. J. 2014. After Lincoln: How the North Won the Civil War and Lost the Peace. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, David Levering. 1993. W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race. New York: Holt. [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm, Charles. 2007. Culture and Authenticy. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lomawaima, K. Tsianina, ed. 2018. Native American Boarding School Stories. Journal of American Indian Education 57: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomawaima, K. Tsianina, and Teresa L. McCarty. 2006. “To Remain an Indian”: Lessons in Democracy from a Century of Native American Education. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lomawaima, K. Tsianina, Brenda J. Child, and Margaret L. Archuleta, eds. 2000. Away from Home: American Indian Boarding School Experiences, 1879–2000, 2nd ed. Phoenix: Heard Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, Jonathan. 1995. Human Biodiversity: Genes, Race, and History. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Maroney, Eric. 2010. The Other Zions: The Lost Histories of Jewish Nations. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, Michele, and Helen Lee, eds. 2012. Reading Colonial Japan: Text, Context, and Critique. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, Jane. 2017. Race, Tea and Colonial Resettlement: Imperial Families, Interrupted. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, Ann. 2015. Illicit Love: Interracial Sex and Marriage in the United States and Australia. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, Ann. 2016. In Choosing to Be Cherokee, She Was Forced to Renounce the US. Zocalo. Available online: https://www.zocalopublicsquare.org/2016/07/28/in-choosing-to-be-cherokee-she-was-forced-to-renounce-the-u-s/chronicles/who-we-were/ (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- McKee, Kimberly D. 2019. Disrupting Kinship: Transnational Politics of Korean Adoption in the United States. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meer, Nasar. 2012. Racialization and Religion: Race, Culture, and Difference in the Study of Antisemitism and Islamophobia. Ethnic and Racial Studies 36: 385–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milloy, John S., and Mary Jane Logan McCallum. 2017. A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School Program, 2nd ed. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Kim Park. 2016. Invisible Asians: Korean American Adoptees, Asian American Experiences, and Racial Exceptionalism. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Arissa H. 2015. To Save the Children of Korea: The Cold War Origins of International Adoption. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. 2014. Racial Formation in the United States, 3rd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, John D. 2010. The Dance of Identities: Korean Adoptees and Their Journey toward Empowerment. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pate, SooJin. 2014. From Orphan to Adoptee: US Empire and Genealogies of Korean Adoption. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peattie, Mark. 1988. Nan’yo: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese in Micronesia, 1885–1945. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peltier, Elian. 2021. Torn From Parents in the Belgian Congo, Women Seek Reparations. New York Times, November 3. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington, Doris, and Nugi Gagimara. 1996. Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Portelli, Alessandro. 2004. The Problem of the Color-Blind: Notes on the Discourse of Race in Italy. In Race and Nation. Edited by Paul Spickard. New York: Routledge, pp. 355–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, R. H. 1908. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Carlisle, Pennsylvania: Its Origins, Purposes, Progress and the Difficulties Surmounted. Carlisle: Cumberland County Historical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Quirin, James. 2010. The Evolution of the Ethiopian Jews: A History of the Beta Israel (Falasha) to 1920. Los Angeles: Tsehai Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Read, Peter. 1999. A Rape of the Soul So Profound: The Return of the Stolen Generations. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Regan, Paulette. 2011. Unsettling the Settler Within: Indian Residential Schools, Truth Telling, and Reconciliation in Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Dorothy. 2012. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century. New York: New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Sean R. 2020. The War on the Uyghurs: China’s Internal Campaign against a Muslim Minority. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-García, Dan, Miguel Solana, Anna Ortiz, and Beatriz Ballestín. 2021. Blurring of Colour Lines? Ethnoracially Mixed Youth in Spain Navigating Identity. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47: 838–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ross, Dorothy. 1991. The Origins of American Social Science, rev. ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sand, Shlomo. 2009. The Invention of the Jewish People. Translated by Yael Lotan. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Schreuer, Milan. 2019. Belgium Apologizes for Kidnapping Children From African Colonies. New York Times, April 4. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Anthony D. 1986. The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Anthony D. 1995. Nationalism and Modernism. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Richard J. 2001. The Many Faces of Korla Pandit. Los Angeles Magazine 46: 73–77, 146–51. [Google Scholar]

- Smithers, Gregory D. 2017. Science, Sexuality, and Race in the United States and Australia, 1780–1940, rev. ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spickard, Paul. 1995. Pacific Islander Americans and Multiethnicity: A Vision of America’s Future? Social Forces 73: 1365–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spickard, Paul. 2015. Race in Mind: Critical Essays. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spickard, Paul. 2020. Shape Shifting: Reflections on Racial Plasticity. In Shape Shifters: Journeys Across Terrains of Race and Identity. Edited by Lily Anne Y. Welty, Ingrid Dineen-Wimberly and Paul Spickard. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Spickard, Paul, and Rowena Fong. 1994. Ethnic Relations in the People’s Republic of China: Images and Social Distance between Han Chinese and Minority and Foreign Nationalities. Journal of Northeast Asian Studies 13: 26–48. [Google Scholar]

- Spinka, Matthew. 1926. The Conversion of Russia. Journal of Religion 6: 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, Claude M. 2010. A Broader View of Identity: In the Lives of Anatole Broyard, Amin Maalouf, and the Rest of Us. In Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do. New York: Norton, pp. 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, Shelley. 1999. “Her Traces Are Found Everywhere”: Shanghai, Li Xianglan, and the ‘Greater East Asia Film Sphere’. In Cinema and Urban Culture in Shanghai, 1922–1943. Edited by Yingjin Zhang. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 225–45. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, Shelley. 2002. A Star by Any Other Name: The (after) Lives of Li Xianglan. Quarterly Review of Film and Video 19: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Alexandra Minna. 2016. Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America, 2nd ed. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sueyoshi, Amy. 2012. Queer Compulsions: Race, Nation, and Sexuality in the Affairs of Yone Noguchi. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, Robert Wald. 2014. The Myth of Race: The Troubling Persistence of an Unscientific Idea. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tepper, Daniel. 2021. Glimpses of ‘Lost Tribe’ Jewish Communities in India and Myanmar. New York Times, September 25. [Google Scholar]

- Toomer, Jean. n.d. Draft autobiography, JWJ MSS. Series 1, b. 18: F. 493. New Haven: Beinecke Library, Yale University.

- Trafzer, Clifford E., Jean A. Keller, and Lorene Sisquoc, eds. 2006. Boarding School Blues: Revisiting American Indian Educational Experiences. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trenka, Jane Jeong, Julia Chinyere Oparah, and Sun Yung Shin, eds. 2005. Outsiders Within: Writing on Transracial Adoption. Boston: South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Mia, and Jiannbin Lee Shiao. 2013. Choosing Ethnicity, Negotiating Race: Korean Adoptees in America. New York: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, William H. 2007. The Funding of Scientific Racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vachkova, Veselina. 2008. Danube Bulgaria and Khazaria as Parts of the Byzantine Oikoumene. In The Other Europe in the Middle Ages: Avars, Bulgars, Khazars, and Cumans. Edited by Florin Curta and Roman Kovalev. Leiden: Brill, pp. 339–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, Nicholas. 2014. A Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race, and Human History. New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yiman. 2011. Affective Politics and the Legend of Yamaguchi Yoshiko/Li Xianglan. In Sino-Japanese Transculturation: Late Nineteenth Century to the End of the Pacific War. Edited by Richard King, Cody Poulton and Katsuhiko Endo. Lanham: Lexington Books, pp. 143–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer, Andreas. 2013. Ethnic Boundary Making: Institutions, Power, Networks. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Winch, Peter. 2008. The Idea of a Social Science and Its Relationship to Philosophy, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, Susie. 2019. Framed by War: Korean Children and Women at the Crossroads of US Empire. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, Yoshiko, and Sakuya Fujiwara. 2015. Fragrant Orchid: The Story of My Early Life. Translated by Chia-Ning Chang. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zima, Peter V. 2015. Subjectivity and Identity: Between Modernity and Postmodernity. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spickard, P. Shape Shifting: Toward a Theory of Racial Change. Genealogy 2022, 6, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy6020048

Spickard P. Shape Shifting: Toward a Theory of Racial Change. Genealogy. 2022; 6(2):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy6020048

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpickard, Paul. 2022. "Shape Shifting: Toward a Theory of Racial Change" Genealogy 6, no. 2: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy6020048

APA StyleSpickard, P. (2022). Shape Shifting: Toward a Theory of Racial Change. Genealogy, 6(2), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy6020048