1. Introduction

From Ta-Nehisi Coates’

Black Panther comics series to the CW’s

Black Lightning television series,

Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings to

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, the last five years have seen a push to bring non-white comics characters into the fore: the inextricable link between comics and racial identity is more apparent than ever. Comics reflect material and experiential questions about the evolution of identity in the United States. This is due, in no small part, to American comics’ emergence during the late 1800s, when racism, segregation, and anti-Black violence became more blatant and severe in the post-Reconstruction Era.

1 Indeed, comic studies as a field have become a vibrant space to discuss the ways identity has been shaped and represented by popular culture discourse.

2While much of the scholarly discourse on race in comics consists of close reading, this analysis seeks to uncover trends at a larger scale using metadata from the Michigan State University Comic Art Collection (CAC) as data. With more than 300,000 print books and artifacts, the CAC provides a cross-section of comic art, comics publishing, and comics collecting throughout the history of the medium. These institutional records have the potential to highlight the ways identity is a fluid outcome of historical circumstances linked to the constructed nature of race. This approach borrows from critical race theory and its emphasis on thinking about the ways institutional practice helps construct our understanding of racial meaning. While metadata cannot produce definitive answers, it can reveal how cultural production, consumer practice, and communal action come together to create race. Indeed, hidden in the collection are examples of resistance to this pattern of othering racial minorities forgotten today.

Hayden White described the future as “a realization of projects performed by past human agents and a determination of a field of possible projects to be realized by living agents…” (

White 2009) The Comic Art Collection and its metadata are two such examples. This collection is the culmination of donations by collectors, careful description by catalogers, and intensive cleaning by researchers. We are heirs to that labor for better and worse: at MSU, we have access to a wealth of knowledge about comic art, comics publishing, and comics collecting; however, we also inherit its failures. The CAC is primarily donation-based, representing a cross-section not just of comics history, but of comics-collecting practices in North America.

3 However, we do not know the demographics, collecting practices, or biases of those donors that may cause gaps in the collection. Catalogers created the metadata that was transformed by the CADNA team into our dataset. We inherit the MARC structure and the LCSH subject headings from the catalogers, and the data cleaning decisions by the CADNA team. This community created the “future” that we now inhabit.

In this article, we provide a brief historical survey of this dataset’s origins, structure, and aims; this survey sets the stage for the ensuing discussion of how its contents shed light on how representations of race are embedded within associated library cataloging and data records. From here, we offer a series of three specialized case studies of the CADNA dataset as in roads to working with a dataset comprised of metadata for over fifty thousand comics from the CAC. Each case study attends to a unique investigation of the CADNA dataset in order to uncover stories of racially minoritized groups and creators embedded or buried within the dataset. The first case study considers the potential to understand racial erasure in North American comics. Next, we offer a genre study of subject headings within the dataset to visualize the contributions of Black and other-persons-of-color representation in horror comics. Our final case study centers a sequence of data visualizations highlighting comics created by Indigenous creators, as well as those that feature Indigenous people. Taken together, these visualizations offer a glimpse on the dynamic way comic art offers a path to reflecting on the complexity of identity in North America. Through these case studies, we visualize the past projects and the future past(s) of comics through the lens of race.

2. History and Structure of the Dataset

This dataset is the result of not only decades of cataloging by both Michigan State University librarians and institutions such as the OCLC, but also years of collaboration between faculty, librarians, and students to extract, reformat, and clean those records. In 2019, a research collaboration of MSU faculty, librarians, and digital humanists formed to develop a research project to study the MSU Comic Art Collection (CAC) as a dataset. The group extracted a subset of all MARC records, representing comic books published in the United States, Canada, and Mexico, totaling just over 50,000. After reformatting the dataset from XML to a tabular structure, the Comics as Data team

4 cleaned publication dates, locations, author names, and publisher names.

5Subject headings proved to be a more complex cleaning endeavor. The subject headings in the Comic Art collection are a mixture of the (

Library of Congress Subject Headings 1993) (LCSH), OCLC FAST terminology, and a handful of terms unique to the collection. (Examples include “Girls’ comic books, strips, etc.” and “Funny kid comic books, strips, etc.”) These subject headings are hierarchical, often including a secondary term to describe the focus within the broader term. For example,

Heaven Sword & Dragon Sabre, a manga series by Ma Wing-shing adapted from the novel by Jin Yong (

Yong and Ma 2002), bears the subject heading “China--History, Military.” (

Heaven Sword n.d.) “China” is the broad term, narrowed by “History, Military,” indicating this comic is about the military history of China. This is helpful from a user perspective, but complex from a data standpoint. If we filter the dataset for “Military History”, this comic will not be included, even though it discusses military history. Furthermore, most records include multiple subject headings, and it proved difficult to programmatically separate these without removing the hierarchical structure. We chose to split subject headings into their own rows, remove their urls, and use a process in OpenRefine called “clustering” to normalize similar subject headings. For each case study in this paper, we used a dataset with a column for the original subject text, the cleaned subject headings split into individual rows, and the cleaned subject headings recombined into one cell.

3. Case Study: Subject Headings and Their Discontents

Before exploring what we can learn from this data in the following case studies, we must first acknowledge the limitations of using catalog data in this way, especially in the context of race. In her article “Classification Along the Color Line: Excavating Racism in the Stacks,” Melissa Adler traces the history of cataloging back to Charles Cutter, whose works

Rules for a Dictionary Catalog, and the unfinished

Expansive Classification, served as models for modern classification systems such as the Library of Congress Classification System. Cutter took an evolutionary approach to classification, placing subjects both within and outside of the natural sciences in a hierarchy as they would “naturally” evolve. For example, as Adler notes, “Freeman, Negroes” was classified at the end of the Education classification, along with other marginalized groups, “distinct from…classes devoted to topics related to education (pedagogy, school subjects, grade levels, etc.) for an assumed white, “able-bodied,” male, propertied American population” (

Adler 2017). Hope Olson calls this Cutter’s “presumption of universality” (

Olson 2001). He developed his scheme and the language he used to represent what he termed the public’s “habitual way of looking at things” (

Cutter 1904), or, as Olsen puts it, the representation of the majority (

Olson 2001).

The subject headings themselves also reflect this universality and hierarchy. Self-described radical librarian Sanford Berman critiques and offers remedies for dozens of problematic Library of Congress Subject Headings in his book

Prejudices and Antipathies. His first example of a problematic term is the subject heading “Jewish question,” and its more general relative, “Race Question,” which describe the debate of the majority on what to do with minorities (

Berman 1993). Berman calls these headings out for their presumption of whiteness and non-Jewishness and the normalization of oppression: “‘Race question’ is the overlord’s terminology, nicely suggesting that the oppressed—not themselves—represent the ‘problem.’…Assign RACE QUESTION as a subhead to the dust-bin, where it belonged from the start.” Similarly, Berman critiques “Negroes as Businessmen,” “Negroes as Farmers” (

Berman 1993) and other similar subheadings under the heading “Negroes” (

Berman 1993), first for their outdated and offensive terminology, and secondly for the use of the word “as” (its implication being that “the occupation or activity that follows is somehow odd, uncommon, or unfitting for ‘Negroes’ to engage in”), and, finally, for the non-existence of “Caucasians as Businessmen” or “Caucasians as Farmers.” Berman’s language is now out of date, but his point still stands: the subject headings treated minorities, particularly Black people, as special cases.

While the headings “Negroes” and “Race Question,” are no longer in use, the principle of universality and hierarchies still exist within the current Library of Congress Subject Headings. For example, the subject heading “Executives” lists among its narrower terms, “Gay executives,” “Women executives,” and “Minority executives;” yet none for “Straight executives,” “Men executives,” or “White executives.” Olson traces this discrepancy back to Cutter’s visions of “a community of library users with a unified perspective and a single way of seeking information,” a community that assumes that all business executives are straight, white, and male unless specified otherwise.

We can see these structures and assumptions reflected in the MSU Library Comic Art data. To gain an overview of what racial identities are represented in the catalog, we totaled up racial and ethnic terms in five categories: African American or Black, Asian American, Indigenous or Indian American,

6 Latin American and Latino, and White and White American (

Table 1). We fully acknowledge that these groupings are problematic. Throughout the catalog, groups are conflated, misnamed, and marginalized through these terms. The data was filtered for values containing each of the above terms, and that data was filtered again to remove any instances in which the term(s) did not describe identity (e.g., “Black markets”, “Indian territory”). We thus included general terms (e.g., “African Americans”) with narrower terms (e.g., “Black Muslims”) to obtain a definitive count.

Headings from

Table 1 describing African Americans numbered the highest at 433, with Indigenous or American Indian headings coming in second at 224. However, only one heading describing white people as a group appears in our entire dataset. The comic in question is titled “Your black friend,” published by Silver Sprocket in 2016. It is notable that this comic is also assigned the subject headings Group identity, Race relations, African Americans, Friendship, and Racism. The only time white identity is noted in our catalog is when it is placed in opposition to another racial group. Representations of white people, individually and as groups, undoubtedly appear in the catalog, but catalogers do not note this in the subject field. We could place blame on the catalogers themselves, but it is clear that some of Cutter’s claim to universality has trickled down into our catalog.

When we plot these frequencies by year (

tophkat 2022a), we see that, other than one exception in 1902, these terms do not start being applied to comics until the mid-1900s. This could signal simply that more diverse identities are represented in comics over time. This increase tracks with the rise of movements against racism and toward civil rights and the rise in popularity of comics in general.

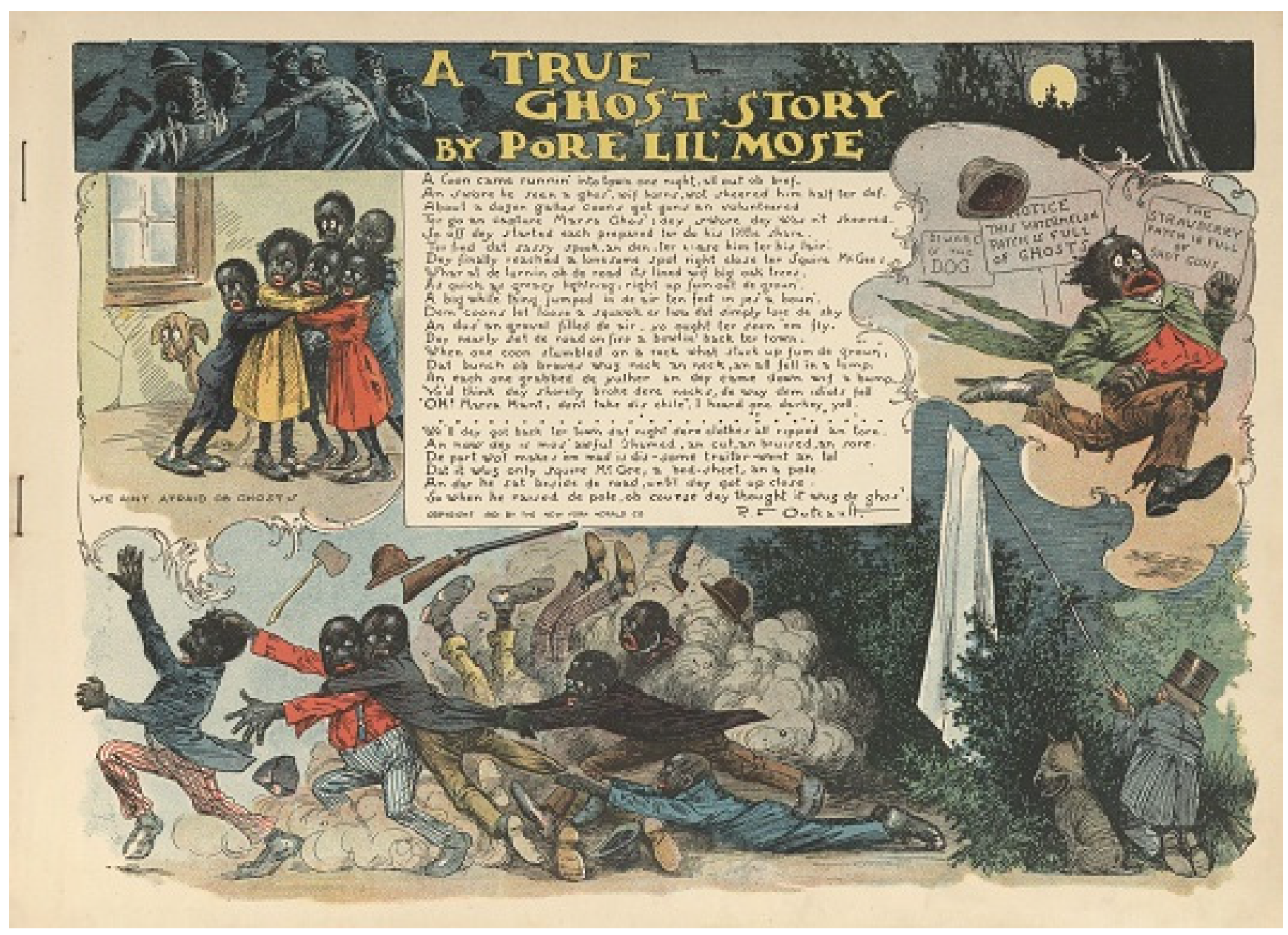

However, these terms do not always indicate respectful representation of the group in question. Many early comics labeled with these subject terms are pure racial caricature. Take, for example, “

Pore lil Mose: his letters to his mammy” from 1902, written by Buster-Brown creator Richard Felton

Outcault (

1902). It depicts a young Black boy, among other Black characters, in a style akin to that used in minstrel shows. Pore lil Mose writes poems framed as letters to his “mammy,” a racist stereotype of Black women domestic workers, in a “Negro” dialect rife with slurs such as “coon” and “darky.” (

Figure 1).

The subject headings assigned to Pore lil Mose are “African American children” and “Comic Books, strips, etc.” While Pore lil Mose is centered on an African American child, the heading “African American children” does not give us the full picture of the racial dynamics at play.

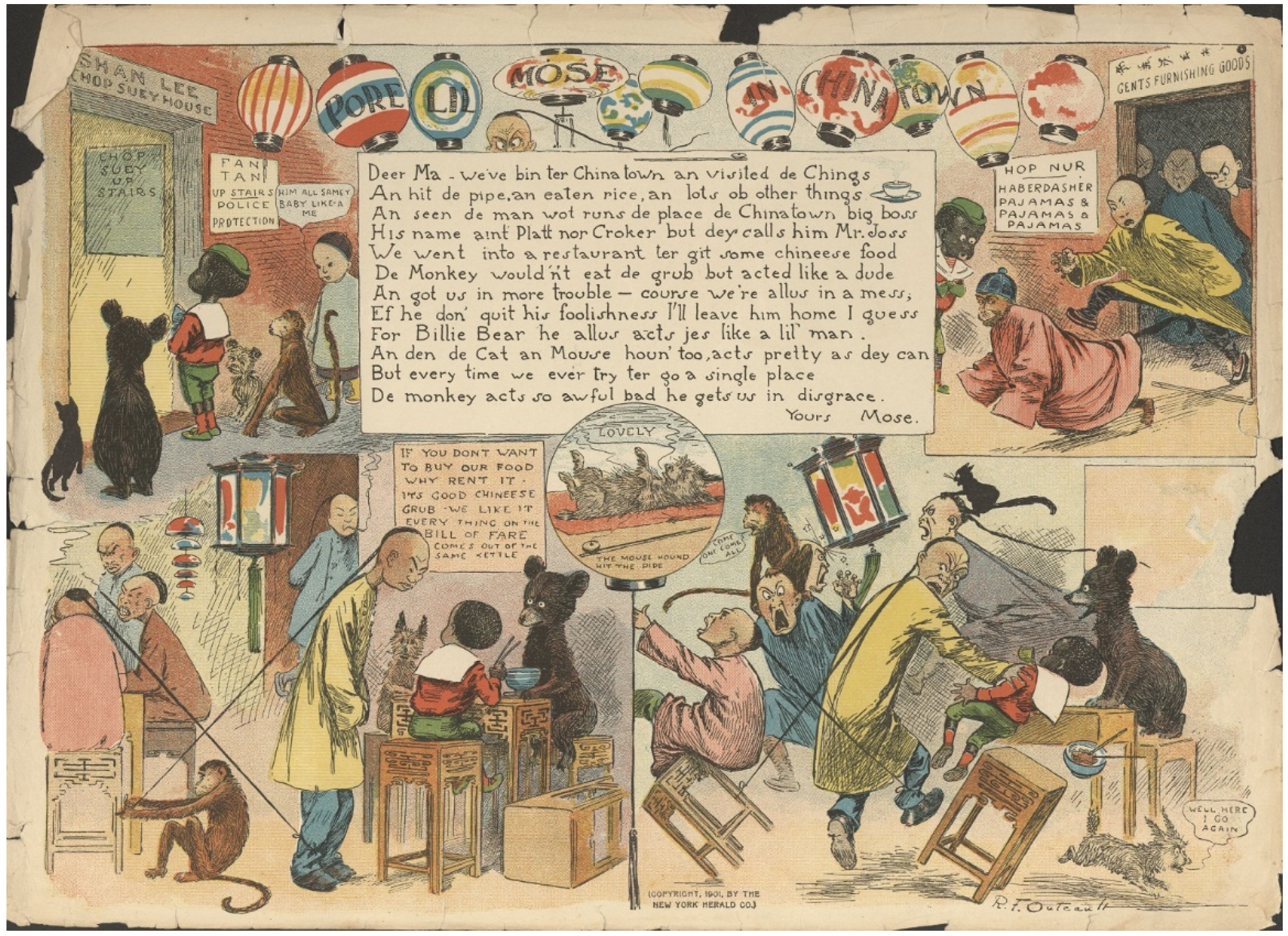

Subject headings also cannot give the full picture of racial representation in each comic. Later on in

Pore lil Mose, we are presented with a letter about his visit to Chinatown, and the representation is no more respectful than that of Mose himself (

Figure 2).

This is because subject headings are typically used to describe what a document is “about,” rather than what it is an instance of. Librarians call this process “determining the aboutness” of a document, and exactly how to do it is an ongoing discussion within library science (

Rondeau 2014). Our catalog has instances of both “is-about” and “instance-of” subject headings. For example, there are over four thousand comics whose subject headings include the word “Horror.” Most of the comics in this subset are instances of comics in the horror genre, but it also includes volumes that delve into the history of that genre in comics.

Where racism is concerned, the subject headings are applied only to comics

about racism rather than to

instances of racism in comics. To return to our previous example, while

Pore lil Mose certainly is an example of racism in comics, it does not bear the “Racism” subject heading. “Racism” does appear as a subject heading 12 times in the catalog, but the term is not assigned to comics published before 1965, and appears most often in the 2010s. The heading “Race Relations” appears starting in 1956, but follows a similar pattern (

tophkat 2022b).

The same pattern emerges here as with terms describing racial groups: as discussions about race, racism, and civil rights emerge and grow over the 20th century, artists and authors begin to explore these issues in comics. The other subject headings in this subset bear out this assumption. Within the subset of comics bearing either the heading “Racism” or “Race Relations,” the phrase “Civil rights” appears 21 times, and “History” appears 20 times. “African American” appears 32 times. These subject headings are meant to help users find comics about racism, and do not allow us to track instances of racism in the catalog.

Subject headings can reveal broad trends within comics: what topics and tropes creators are interested in, which genres emerge and develop over time, and how comics intersect with major historical movements. However, these views are limited by an assumed whiteness. All description of race in the catalog presents non-white identities as “others,” and presents racism as a problem for minorities. Nevertheless, subject headings provide an inroad to this data that is otherwise unavailable to us: an imperfect view into what catalogers think is most helpful to users—for better and for worse.

4. Case Study: Looking at Horror Comics and Author Representation

A hierarchical visualization (

Huff 2022) begins a conversation surrounding a subset of our Comics Arts Collection (CAC) dataset—horror comics. This visualization was created to explore broader questions about author representation in horror comics. Historically, horror has not been accurately representative of Black people or other people of color. For instance, Black people were often depicted stereotypically or simply as markers of difference for other white characters, such as in blaxploitation films and comics that developed from those films. And, as Frances Gateward and John Jennings explain in

Blacker the Ink, “Comics traffic in stereotypes and fixity” as well as “[A]bstract and simplify.” (

Gateward and Jennings 2015). In other words, representations of Black people and other people of color in comics, especially in the horror genre that has historically represented Black people and people of color stereotypically, are limited in comics and rooted in stereotypes in a way that simplifies the experiences of these marginalized groups. To explore these issues of representation in horror comics, the creation of this visualization opened up a few questions: (1) Who are the most-represented horror creators in this collection? and (2) What are the topics or themes depicted in the horror comics that are most represented? Overall, these questions point toward a lack of representation, or a silencing, of BIPOC horror-comics creators, despite the representation of BIPOC individuals and narratives in the horror comics that are the most prevalent in the CAC.

The data used to create this visualization only considers horror comics from the CAC that include authors and dates assigned to comics tagged with the description “Horror” or “Horror comics” (as the item’s first descriptive tag). After this cleaning, it was discovered that 4394 total items from the collection are given the first descriptive subject heading of “horror” or “horror comics.” Out of the 4394 horror comics in the collection, only 1255 items had authors and dates assigned to them.

With these 1255 usable items, this visualization was created to depict the number of horror comics in the CAC in a hierarchical circle chart, where the usable data is grouped by author with their attributed works from the collection included in their respective circles. This visualization can also be sorted by the year of publication. The largest circles, pulled toward the middle of the visualization, represent the creators with the most horror comics in the collection, whereas the smaller circles on the outside indicate the creators with the fewest horror comics. From this, the data visualization shows that the most-represented horror-comics creator in the collection is Mike Mignola with a total of 74 items assigned to him, and the second-most-represented creator to be Steve Niles with 30 items, as they are at the center of the visual with the largest circles. While these are white creators, at times they do take up semi-racial narratives through uses of mythology and folklore. Namely, Mike Mignola’s comics often adopt Irish and Russian folklore to explore and critique both mythology and historical events.

Mignola’s most-notable works in the collection are the

Hellboy series and the

Hellboy spin-offs such as the

Hell on Earth series. Mignola’s

Hellboy comics follow the main character, Hellboy, and, according to comics scholar Joseph Michael Sommers in an essay about

Hellboy: The Crooked Man, “Mignola creates Hellboy as a piece of walking modern mythology who mingles in and out of established history” (

Sommers 2011). Sommers’ message is clear—Mignola’s popular character, Hellboy, is based on mythology and is meant to interact with a fictitious reimagining of real historical events and mythology. While these mythologies are meant to demonstrate real historical happenings and their effects on marginalized groups on an international scale through fiction, these are still largely Anglo and mostly white characters and narratives, since Mignola pulls from Irish folklore. The focus on Irish folklore does imply a certain racial narrative when considering the history of race in the U.S. and the prejudices toward Irish people in the late nineteenth century, but, as Lauren O’Connor explains, Mignola’s work “[E]xemplifies the role of folklore in nation-building” and the use of Irish folklore in Mignola’s comics relates to a revival of Irish folk culture, which is “[L]aced with a millennialist hope that the turn of the twentieth century would witness the culture and political decolonization of Ireland” (

O’Connor 2010). In other words, Mignola’s comics, although still very Anglo focused, do carry a decolonization narrative through a preserving of the folklore of marginalized people. While even this focus on Mignola’s contributions as the most-prevalent horror creator in the collection enacts a silencing on the already marginalized BIPOC authors in this subset, it is important to look at how white horror-comics authors are taking up semi-racial narratives when looking at author representation in horror comics. However, it still must be problematized that the horror comics with the most representation are created by a white author and those comics mostly consist of Anglo narratives.

BIPOC authors do not take up a noticeable amount of space in this subset of the collection, unless one knows of BIPOC horror authors’ works and publication dates. With that prior knowledge, one can sort the visual by publication year to more easily find BIPOC authors. However, when looking at “all” publication dates, the most notable BIPOC contributor shown in this visual is Junji Ito, the author of Uzumaki: Spiral into Horror, with a total of 6 items attributed to them. While this author is toward the center of the visual, they are still silenced. They are still largely unnoticeable in the visualization as one must hover over their circle for their name to even show up (this is the circle next to Gary Reed, who only has 5 more items attributed to them in this collection). Junji Ito’s circle is probably the most space taken up in the visual by a BIPOC creator, despite there being others in the collection.

From this visualization, we can conclude that there is a trend in horror comics of silencing or displacing the voices of marginalized people. The visualization can be read as a metaphor for author representation in horror comics—white voices are centered while BIPOC voices are silenced or pushed to the margins. In a literal sense, the visualization pushes those not represented to the outskirts of the overall visual, while those with the most representation, white authored works, are centered. Despite the topics of folklore and semi-racial narratives covered in the works created by white authors as seen in Mignola’s work, there is still a lacking representation of horror comics created by BIPOC authors in this dataset, despite the growing number of BIPOC authors in horror comics such as John Jennings, Junji Ito (who has 6 items attributed to them in the visualization), and Micheline Hess.

7 In future visualizations, it could be telling to explore horror comics and author representation by looking at titles with horror-related subject headings without any attributed authors, to see how many of those titles without attributed authors are works by BIPOC authors.

5. Case Study: Indigenous Comics and Creators

As a land-grant institution, “Michigan State University occupies the ancestral, traditional, and contemporary Lands of the Anishinaabeg—Three Fires Confederacy of Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples.” This land acknowledgement is also representative of an ongoing responsibility to support Indigenous people, communities, and nations in Michigan, as well as across North America. Since the Comic Arts Collection is literally housed on this occupied land, it becomes even more imperative to understand Indigenous peoples’ representation within MSU’s collections, as well as their lack of representation, at the same time as we acknowledge the differences between race, ethnicity, and indigeneity therein. As a primarily donation-based special collection, there are limits to its curatorial reach, of course; it is dedicated to archiving and preserving North American comic books of all stripes. But a case study of the CaDNA dataset reveals a near-microscopic percentage of the representation of Indigenous creators, stories, and characters represented within the MSU Comic Arts Collection.

This series of visualizations highlights the small representation of comics that have forms of “Indigenous” metadata subject headings attached to them. Subjects include “Indians of North America;” “Indians of South America;” “Indian reservations;” “Indigenous peoples;” etc., as well as more-specialized subject headings referring to specific tribes: Apache, Nez Perce, Comanche, Creek, Dakota, and the like. In total, the dataset features only 86 comics that have Indigenous headings, out of nearly 47,000 North American comics, itself a snapshot of the much larger Comic Arts Collection with over 300,000 items. This means that comics with Indigenous-related subject headings make up around 0.18% of the entire dataset, a disheartening figure indeed. Each of these visualizations demonstrate the collection’s growth of such comics items over time.

Figure by Justin Wigard on 23 Feburary 2022 (

Wigard 2022a), a line graph organized by area, depicts this growth in a static image. As a stacked percentage-based visualization, it depicts growth over time, comparing Indigenous comics and the rest of the dataset. Of particular note within this visualization are two gaps within the Indigenous comics line, where no Indigenous comics are represented within the dataset. The first is a lack of Indigenous comics and graphic media from 1888–1936. The second is a gap from 1954 to 1974. A third, smaller gap exists between 1979 and 1989. As a primarily donation-based special collection, the MSU Comic Art Collection is somewhat relegated to what is donated, meaning that significant comics featuring Indigenous people published during these gaps were not donated, or may not have been labeled with this primary marker. Creating this visualization also reveals a demonstrable rise in comics with Indigenous-related subject headings from 2007–2018. Such a rise is correlative with the rise in Indigenous-comics creators as well as Indigenous-comics publishers such as Strong Nations and Native Realities.

Figure by Justin Wigard on 16 May 2022 (

Wigard 2022b), features two pie graphs, showing the dataset over time. The first pie graph shows the collection’s Indigenous comics against the whole set in a given year; the second breaks this down further, simply showing the Indigenous comics amidst the rest of the comics in a given year. In contrast to the line graph, these two pie graphs show the relatively small portion of Indigenous comics amidst the rest of the North-American comics. These visualizations, however, fall short in adequately representing these comics without finding each item within the collection itself, or without the kinds of intensive-close-reading-befitting time, effort, and expertise.

In her astute assessment of MSU’s engagement and cataloging of

Wimmen’s Comix, Margaret Galvan notes that “Total coverage may be an impossible task” in providing information about comics, “since one comic alone could involve more than a dozen creators whose work would need cataloging in addition to the indexing of the title itself” (

Galvan 2017). Extrapolating this to the cataloging of these Indigenous comics, we do see similar trends. Anthologies such as

Sovereign Traces feature editorial work by Indigenous creators—in this case, Elizabeth LaPensée and Gordon Henry—curating comics by Indigenous creators in a collected volume. The necessary limitations to this metadata organization would make listing all eighteen creators to be something of an unwieldy task, but their work is indeed represented within the catalog.

The sub-section of this dataset is small enough that a final visualization could be created which visualizes the covers to many of these comics. Figure by

Wigard (

2022c) responds to Frederick Luis Aldama writing in the edited collection

Graphic Indigeneity, that comics scholars must shed critical light on “how mainstream comics have clumsily (mostly) distilled and reconstructed Indigenous identities and experiences of

terra America and Australasia” (

Aldama 2020). Through this process, a cursory glance reveals the deeply problematic and stereotypical ways in which Indigenous people have been depicted in comics throughout history. Indeed, many of these comics fall into or deploy five common tropes outlined by Camille Callison, Niigaanwewidam Sinclair, and Greg Bak: The Warrior, The Artifact, The Sidekick, The Shaman, and The Wannabe (

Callison et al. 2019)

8. One need only look at the earliest items in this visualization to see these racialized depictions.

This reveals a common narrative of white authors speaking for Indigenous people, a particularly problematic narrative in a visual medium such as comics, where white authors have drawn Indigenous people in racist, stereotypical ways. However, Aldama further states that “not all non-Indigenous-created comics get it wrong.” (

Aldama 2020) Comics such as

Scalped by Jason Aaron and R. M. Guéra or

Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain: The Story of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce by Agnieszka Biskup and Rusty Zimmerman do offer more nuanced and thoughtful graphic representations of Indigenous people. Callison, Sinclair, and Bak note that these comics merit significant inclusion in comics archives, as they help represent the diversity of how Indigenous experiences are embodied in graphic narratives (

Callison et al. 2019). Yet, with roughly 100 comics out of this data labeled with Indigenous subject headings, fewer than fifteen of these comics have Indigenous creators associated with them.

Indeed, this visualization serves a dual purpose: highlighting the Indigenous creators represented within the MSU Comic Arts Collection. Because the MSU Comic Arts Collection’s curation is necessarily broad, it becomes ever more imperative to highlight what Indigenous representation does exist, particularly the efforts of Indigenous creators. And yet, these efforts are necessary in cases such as this subset of Indigenous comics. Galvan asks “What other methods might we develop to catalog this material rather than the standard of titles, years, and publication information?” (

Galvan 2017). Presenting these Indigenous comics and their creators in such a visual index answers the call by Galvan for alternative methods of representation and organizing comics collections and archives, as well as Aldama’s call for scholarship that platforms Indigenous creators. Thus, each Indigenous creator has a brief biographical introduction that provides crucial critical context for their contributions and a link to their larger corpus or portfolio. Flourish also allows for the connection of these biographical cards with the cover images and metadata associated with their items in the MSU Library. Generating this visualization provides additional platforming for Indigenous creators, increasing the visibility of not just their contributions collected within the collection, but their creative work overall.

6. Conclusions: The Beginning of the Conversation

Together, these visualizations gesture to new and ongoing engagements with the MSU Comic Art Collection, which was “begun in 1970, by Professor Russel Nye, as part of the collection now called the Russel B. Nye Popular Culture Collection.” As Randall W. Scott further notes, “the need for this collection will increase steadily as remote users, who already need the materials, discover that it exists;” building on this foundation, these visualizations increase access to the collection for remote and distance users, illustrating ongoing stories of race and representation in American comic books (

Scott 2013). Due to the sheer scale of the collection, visualizations such as these highlight trends and avenues for closer reads of primary texts in the CAC, or even areas that merit visits to the collection.

These case studies should not be considered final or ultimate illustrations of trends in the collection; more visualizations can and should be created that call further attention to untold stories around race relations in American comics. Our case studies primarily focus on uncovering whiteness, constructing identity, highlighting Black representation in one particular genre, and showcasing complicated representations of Indigenous people in comics production. As such, these are imperfect understandings of the past, but they provide a more-complicated and three-dimensional view of race and identity as imbricated in American comics history. Additional case studies and perspectives are needed to understand not only the legacies of race in American comics, but how these historical artifacts have themselves shaped public perceptions of race on a large scale.

Rather, these visualizations demonstrate new methods of approaching the Comic Art Collection, to be sure, and American comics more broadly. We hope these case studies will inspire future collaborators that work with the MSU Comics as Data: North America dataset and generate new case studies in conversation with the MSU Comic Art Collection. We recognize that not all those with access to special collections of comics will have the necessary resources, bandwidth, skillsets, etc., to generate datasets, digital visualizations, and the like. In our case, these visualizations would not have been possible without the contributions of past digital historians, staff, and the specialists at MSU who put the dataset together, nor without the curatorial efforts of Randy Scott. We offer these analyses in order to see more scholarship highlighting the contributions of minoritized comics creators in American comics; further interactive maps or graphs that demonstrate ways in which PoC have pushed back on traditionally hegemonic and white comics-publishing practices; and increased extrapolations and applications of these approaches to additional comics collections with different specializations. Each new data visualization and resulting case study of race and representation in comics, particularly in a special collection, contributes to a larger and continuing conversation about the genealogy of comics history, and of race relations as intrinsically tied within their material production in North America.