Indigenous Virginia Digital Storytelling Project: A Creation Story

Abstract

Preface

1. Introduction

2. Making Connections, Building Relations

2.1. The Tour

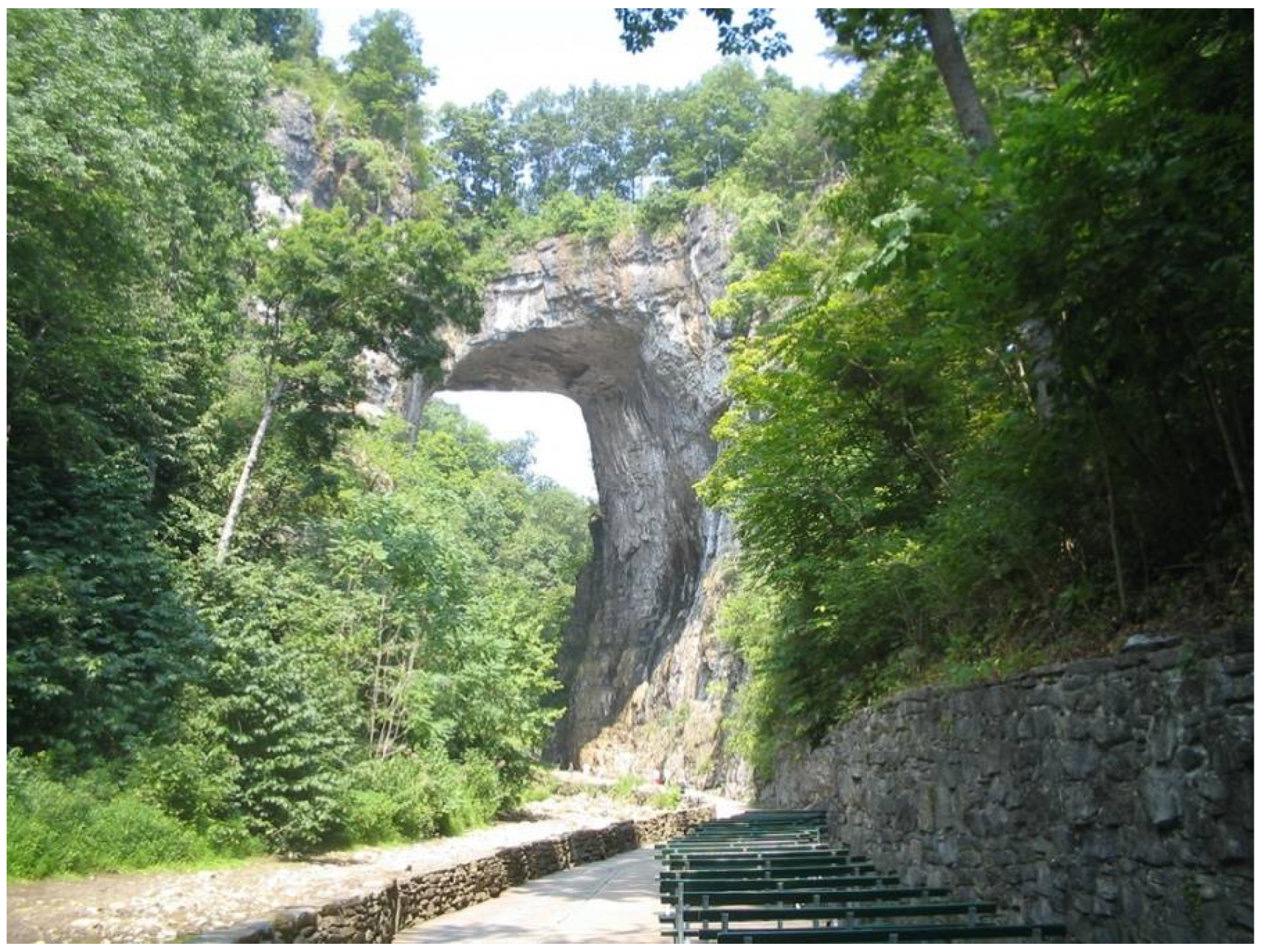

2.2. Mohomony (The Natural Bridge): A Tale of Two Stories

2.3. The Archives

“With one exception, indigenous voices are absent from the content of these archival holdings… Collections belonging to the pre-contact and colonial periods make mention of Indigenous peoples as geographical reference points and as threats to life and property. Allusions to the successful amalgamation and erasure of Indigenous peoples are also prevalent, even in the James Logan Address, the lone indigenous voice among all materials reviewed, and seem to stand as self-validation that destiny was indeed manifest. For collections belonging to the 19th and 20th centuries, [state] Indians are mentioned almost exclusively in relation to the land from which they have been displaced. The [Native] Indian Tribe, which gave title to the only photograph of Indians found in this survey, are staged as backdrop to a group of white men that includes future [state] governor [redacted]—serving as graphic representation of who is telling these stories and of the innate value that such perspective is assumed to have… This Survey of Indigenous materials hoped to uncover stories that would stand as testament of the self-determination long denied to descendants of local Indigenous peoples. Instead, months of exploration yielded traces too faint to disentangle from that of the settler’s gaze. This project’s findings, much like Saidiya Hartman once declared, ‘intend both to tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling.’ We at the [University name] Library now have an opportunity to strengthen our foundation within the larger community by centering voices and exchanges long overdue, and thus contribute to making the impossible possible and the good great”.

3. Digital Storytelling as Both Process and Product

4. What Do We Do with All These Data?

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | StoryMap is easily accessible for sharing and displaying stories, but one limitation is its pricing. Therefore, this would be hosted by the university, and stories submitted outside of DST workshops would have to be collected and built into the StoryMap. |

References

- Ahenakew, Cash. 2016. Grafting Indigenous Ways of Knowing Onto Non-Indigenous Ways of Being The (Underestimated) Challenges of a Decolonial Imagination. International Review of Qualitative Research 9: 323–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ArcGIS StoryMap. n.d. Environmental Systems Research Institute. Available online: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-storymaps/overview (accessed on 14 May 2021).

- De Master, Kathryn Teigen, and Jess Daniels. 2019. Desert wonderings: Reimagining food access mapping. Agriculture and Human Values 36: 241–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, Warren. 2004. The Black & White World of Walter Plecker. Style Weekly. Available online: https://www.styleweekly.com/richmond/the-black-and-white-world-of-walter-plecker/Content?oid=1381080 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Gubrium, Aline. 2009. Digital storytelling: An emergent method for health promotion research and practice. Health Promotion Practice 10: 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubrium, Aline C., Elizabeth L. Krause, and Kasey Jernigan. 2014. Strategic Authenticity and Voice: New Ways of Seeing and Being Seen as Young Mothers Through Digital Storytelling. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 11: 337–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, Siobhan M., and George C. Homsy. 2020. Stories from North of Main: Neighborhood Heritage Story Mapping. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 24: 950–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, Saidiya. 2008. Venus in Two Acts. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, Dallas, and Shaun A. Stevenson. 2017. Decolonizing geographies of power: Indigenous digital counter-mapping practices on turtle Island. Settler Colonial Studies 7: 372–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones Brayboy, Bryan Mckinley, and Emma Maughan. 2009. Indigenous Knowledges and the Story of the Bean. Harvard Educational Review 79: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallaher, Amelia, and Alyson Gamble. 2017. GIS and the humanities: Presenting a path to digital scholarship with the Story Map app. College & Undergraduate Libraries 24: 559–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Joe, and Brooke Hessler. 2018. Digital Storytelling: Capturing Lives, Creating Community. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- LANDBACK Manifesto. n.d. LANDBACK. Available online: https://landback.org/manifesto/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Louis, Renee Pualani, Jay T. Johnson, and Albertus Hadi Pramono. 2012. Introduction: Indigenous Cartographies and Counter-Mapping. Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 47: 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchesi, Annita Hetoevėhotohke E. 2018. “Indians Don’t Make Maps”: Indigenous Cartographic Traditions and Innovations. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 42: 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, Kevin Noble. 2006. The Pocahontas Exception: The Exemption of American Indian Ancestry from Racial Purity Law. Michigan Journal of Race and Law 12: 351–86. Available online: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol12/iss2/3 (accessed on 4 May 2021). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McGurk, Thomas J., and Sébastien Caquard. 2020. To what extent can online mapping be decolonial? A journey throughout Indigenous cartography in Canada. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 64: 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Million, Dian. 2009. Felt Theory: An Indigenous Feminist Approach to Affect and History. Wicazo Sa Review 24: 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahabe Durand, Hannivett. 2020. Final Report: Survey of Indigenous Materials in The Archives: Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Charlottesville: University of Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak, Shiri, Hayden King, and Riley Yesno. 2019. Land Back: A Yellowhead Institute Red Paper. Toronto: Yellowhead Institute, Ryerson University, pp. 1–68. Available online: https://redpaper.yellowheadinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/red-paper-report-final.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Reilly, Philip, and Margery Shaw. 1983. The virginia racial integrity act revisited: The Plecker-Laughlin correspondence: 1928–1930. American Journal of Medical Genetics 16: 483–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, Richard B. 1988. “The Last Stand”: The Fight for Racial Integrity in Virginia in the 1920s. The Journal of Southern History 54: 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, Edgar Winston. 1968. Geology of the Natural Bridge, Sugarloaf Mountain, Buchanan, and Arnold Valley Quadrangles, Virginia; Report of Investigations No. 13; Richmond: Virginia Division of Mineral Resources, Commonwealth of Virginia Department of Conservation and Economic Development, pp. 1–93. Available online: https://www.dmme.virginia.gov/commercedocs/RI_13.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Steinauer-Scudder, Chelsea. 2018. Counter Mapping. Emergence Magazine. February 8. Available online: https://emergencemagazine.org/film/counter-mapping/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Watts, Vanessa. 2013. Indigenous Place-Thought and Agency Amongst Humans and Non Humans (First Woman and Sky Woman Go On a European World Tour!). Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 2: 20–34. Available online: https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/19145 (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Wikimedia Commons. 2020. The Free Media Repository. Natural Bridge. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Natural_Bridge.jpg&oldid=454930578 (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Yazzie, Melanie, and Cutcha Risling Baldy. 2018. Introduction: Indigenous peoples and the politics of water. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 7: 1–18. Available online: https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/30378 (accessed on 10 May 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jernigan, K.; Roach, B. Indigenous Virginia Digital Storytelling Project: A Creation Story. Genealogy 2021, 5, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5040088

Jernigan K, Roach B. Indigenous Virginia Digital Storytelling Project: A Creation Story. Genealogy. 2021; 5(4):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5040088

Chicago/Turabian StyleJernigan, Kasey, and Beth Roach. 2021. "Indigenous Virginia Digital Storytelling Project: A Creation Story" Genealogy 5, no. 4: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5040088

APA StyleJernigan, K., & Roach, B. (2021). Indigenous Virginia Digital Storytelling Project: A Creation Story. Genealogy, 5(4), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5040088