Parochial Linguistic Education: Patterns of an Enduring Friction within a Divided Catalonia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

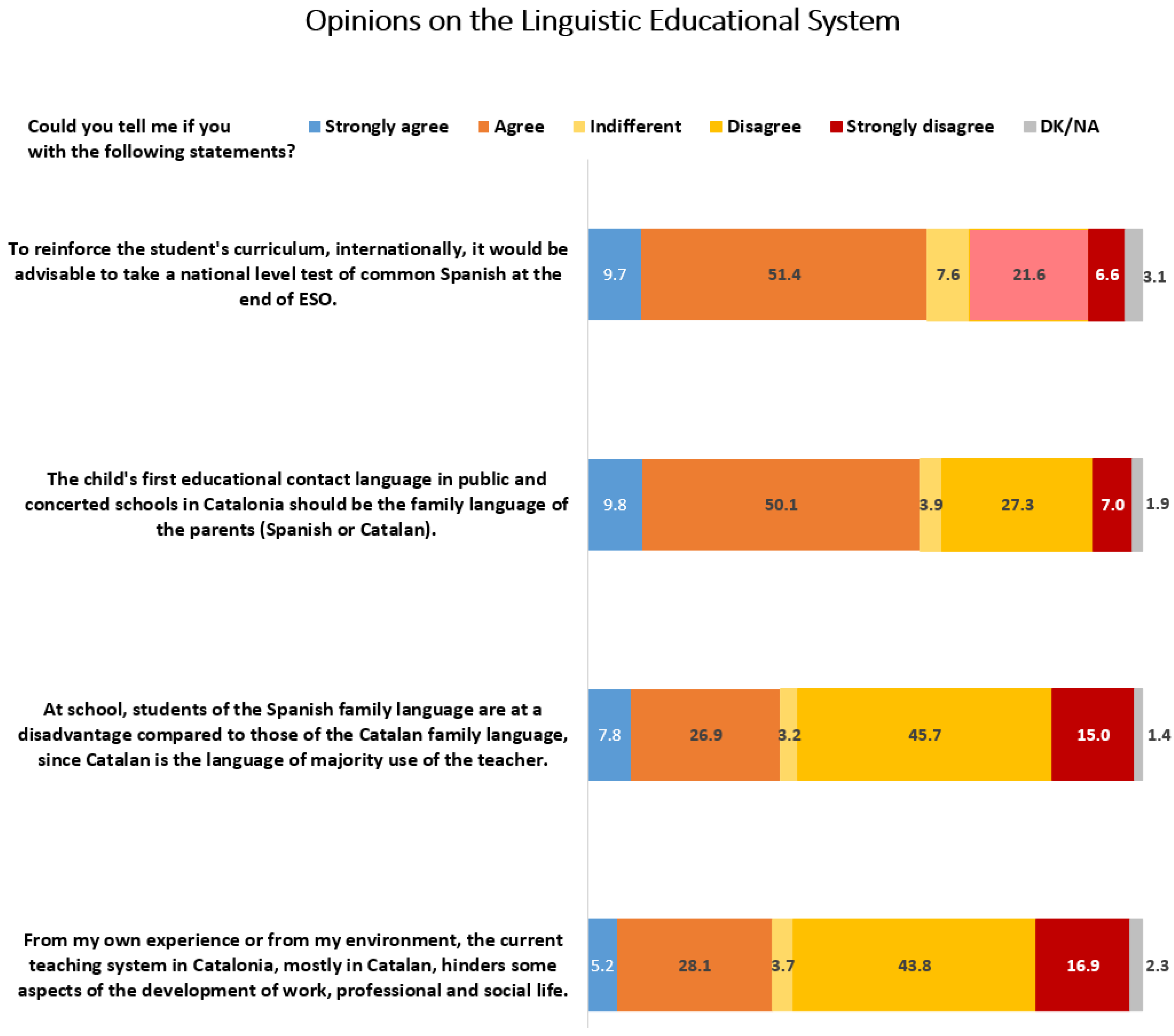

- a.

- Preferences about the Catalonian linguistic educational system.

- b.

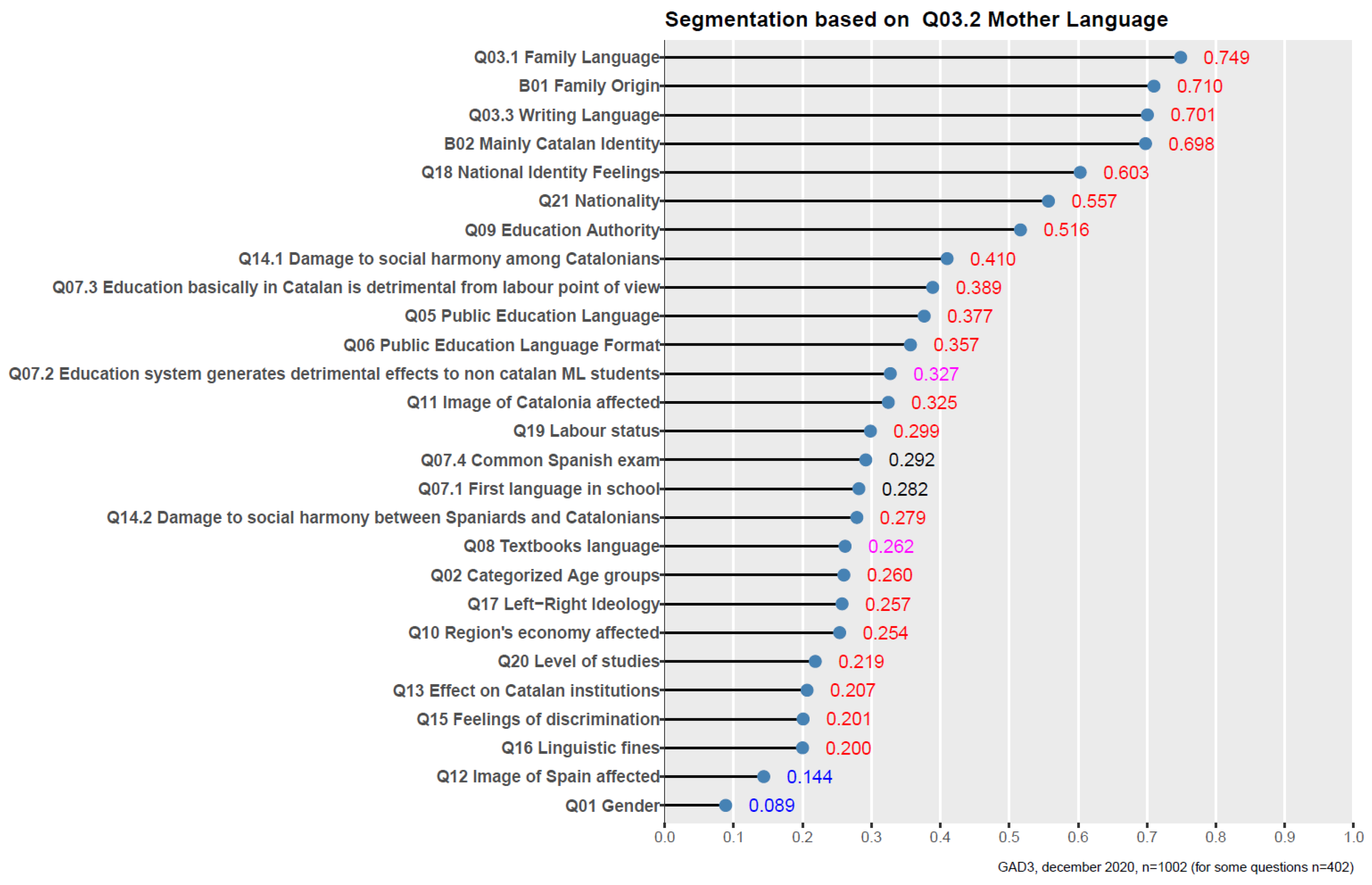

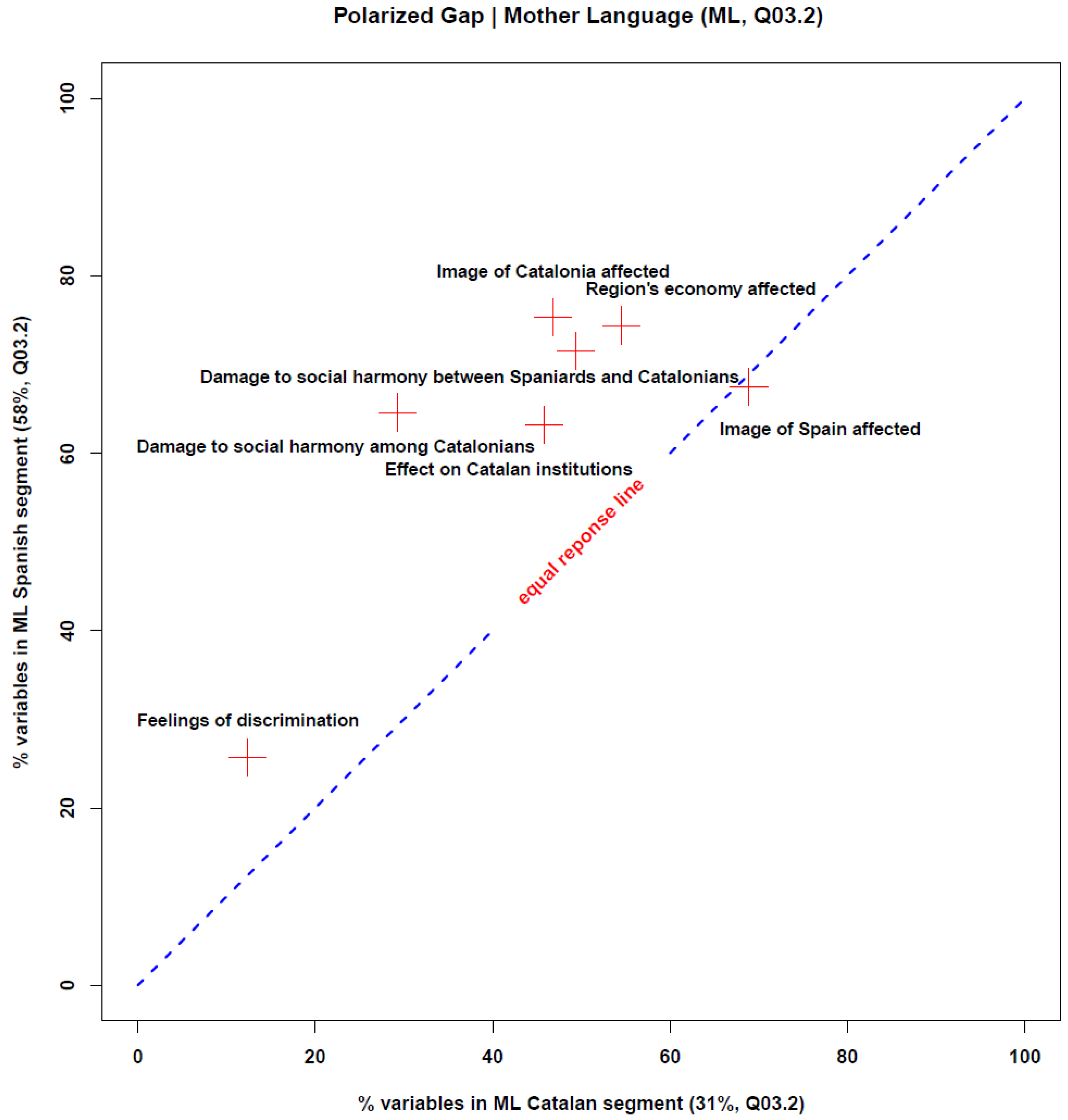

- Segmentations according to different categories.

- b.1.

- Linguistic segmentation based on Q03.2 (Mother Language):

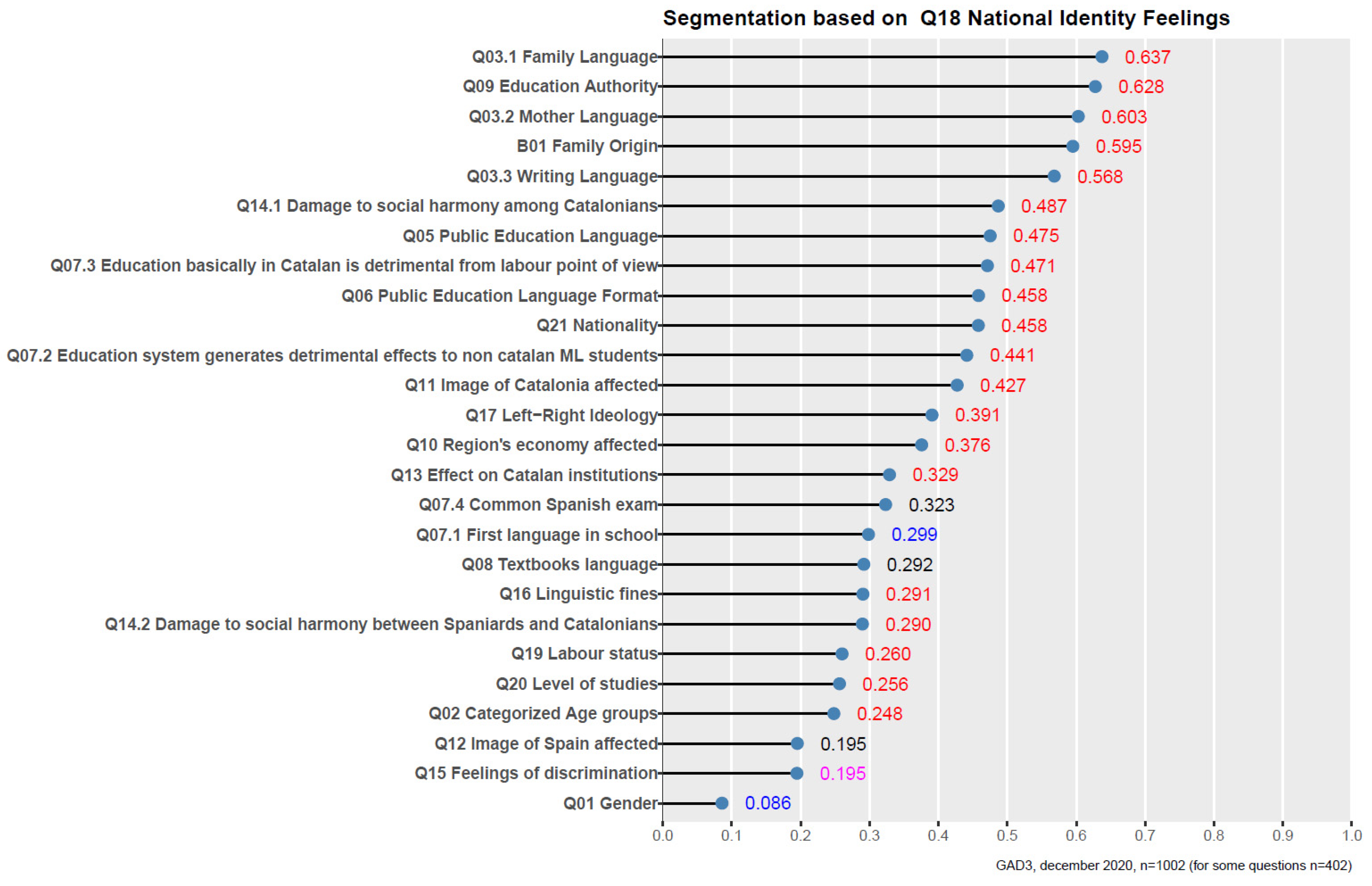

- b.2.

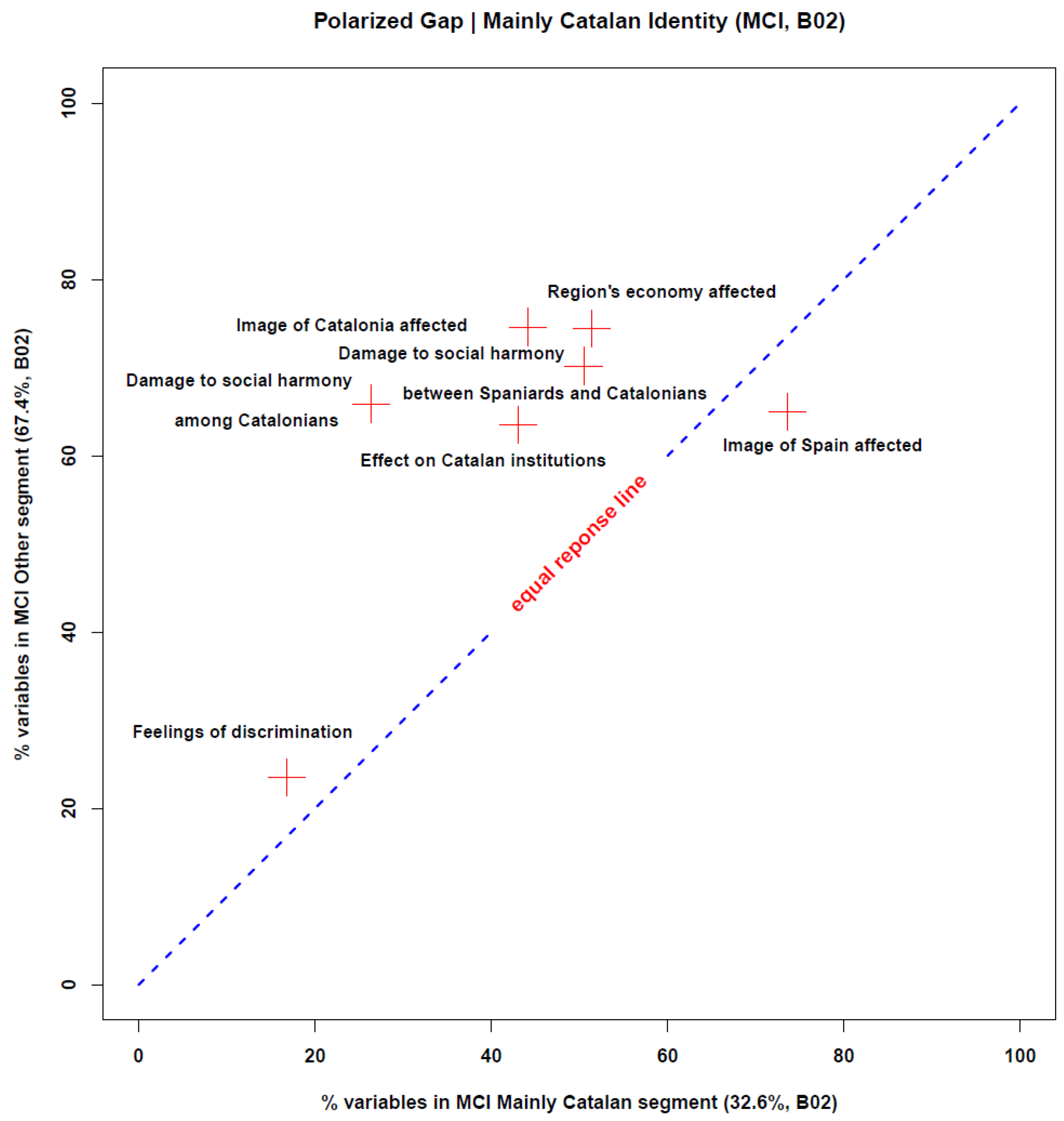

- “Feelings of national identity” segmentation (variable Q18):

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics

References

- Amat, Jordi. 2017. La Conjura de los Irresponsables. Barcelona: Anagrama. [Google Scholar]

- Arnau, Jordi, ed. 2013. Reviving Catalan at School: Challenges and Instructional Approaches. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Aspachs-Bracons, Oriol, Irma Clots-Figueras, Joan Costa, and Paollo Masella. 2008a. Compulsory language educational policies and identity formation. Journal of European Economic Association: Papers and Proceedings 6: 433–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspachs-Bracons, Oriol, Irma Clots-Figueras, and Paollo Masella. 2008b. The effects of language at school on identity and political outlooks. European University Institute-Working Papers. MWP-2008/36. Available online: https://cadmus.eui.eu//handle/1814/9854 (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Aznar-Casanova, José Antonio, José Manuel Gavilán, Manuel Moreno Sánchez, and Juan Haro. 2020. The emotional attentional blink as a measure of patriotism. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 23: e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balcells, Laia, José Fernández-Albertos, and Alexander Kuo. 2021. Secession And Social Polarization: Evidence From Catalonia; WIDER Working Paper 2021/2. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER. Available online: https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2021/936-5 (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Baldoli, Roberto, and Elisabetta Mocca. 2021. Rescuing national unity with imagination: The case of Tabarnia. Nations and Nationalism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretxa, Vanessa, Llorenç Comajuan, Josep Ubalde, and Francesc Xavier Vila. 2016. Changes in the linguistic confidence of primary and secondary students in Catalonia: A longitudinal study. Language, Culture and Curriculum 26: 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Steven. 2020. Language attitudes in Catalonia: A contemporary perspective seen from proindependence sociopolitical organizations. International Journal of Iberian Studies 33: 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, Jorge, and Álvaro Choi. 2019. Efectos de la Inmersión Lingüística Sobre el Alumnado Castellano-Parlante en Cataluña. Madrid: Fundación Europea Sociedady Educación. Available online: https://www.sociedadyeducacion.org/site/wp-content/uploads/SE-Inmersion-Cataluna.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Capellari, Lorenzo, and Antoni Di Paolo. 2015. Bilingual Schooling and Earnings: Evidence from a Language-in-Education Reform. Working Paper, XREAP2015-03. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/xrp/wpaper/xreap2015-03.html (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Clots-Figueras, Irma, and Paollo Masella. 2013. Education, Language and Identity. The Economic Journal 123: 332–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cussó, Roser, Lluis Garcia, and Imma Grande. 2018. The meaning and limitations of the subjective national identity scale: The case of Spain. Ethnopolitics 17: 165–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nieves, Arturo, and Carlos Diz. 2019. Dual identity?: A methodological critique of the Linz-Moreno question as a statistical proxy of national identity. Revista Española de Ciencia Política 49: 13–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, John Huxtable. 2018. Scots and Catalans: Union and Disunion. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- GAD3. 2015. La sociedad catalana ante las elecciones del 27S. Encuesta para SCC. September 2015. Available online: https://societatcivilcatalana.cat/ (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Garvía, Roberto, and Andrés Santana. 2018. El Consenso de la Inmersión Lingüística: Realidad o Mito. Politikon. February 6. Available online: https://politikon.es/2018/02/06/el-consenso-de-la-inmersion-linguistica-realidad-o-mito/ (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Garvía, Roberto, and Andrés Santana. 2020. The linguistic regime in Catalan schools: Some survey results. European Journal of Language Policy 12: 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GESOP. 2017. L’ÒMNIBUS DE GESOP. Preguntes formulades per SCC. February 2017. Available online: https://societatcivilcatalana.cat/ (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Guinjoan, Marc, and Toni Rodón. 2015. A scrutinity of the Linz-Moreno question. Publius-The Journal of Federalism 46: 128–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hierro, Maria Jose, and Didac Queralt. 2021. The divide over independence: Explaining preferences for secession in an advanced open economy. American Journal of Political Science. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguet, Ángel. 2014. Latin American students and language learning in Catalonia: What does the linguistic interdependence hypothesis show us? The Spanish Journal of Psychology 17: e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Huguet, Ángel, José Luis Navarro, Silvia-Maria Chireac, and Clara Sansó. 2013. The acquisition of Catalan by immigrant children: The effect of length of stay and family language. In Reviving Catalan at School: Challenges and Instructional Approaches. Edited by Joaquim Arnau. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ianos, Maria-Adelina, Ángel Huguet, Judit Janés, and Cecilio Lapresta-Rey. 2017a. Can language attitudes be improved?: A longitudinal study of immigrant students in Catalonia (Spain). International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 20: 331–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianos, Maria-Adelina, Ángel Huguet, and Cecilio Lapresta-Rey. 2017b. Attitudinal patterns of secondary education students in Catalonia: The direct and moderator effects of origin. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 38: 113–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianos, Maria-Adelina, A. Rusu, Ángel Huguet, and Cecilio Lapresta-Rey. 2020. Implicit language attitudes in Catalonia (Spain): Investigating preferences for Catalan or Spanish using the Implicit Association Test. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapresta-Rey, Cecilio, Ángel Huguet, and Alberto Fernández-Costales. 2017. Language attitudes, family language and generational cohort in Catalonia: New contributions from a multivariate analysis. Language and Intercultural Communication 17: 135–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepic, Martin. 2017. Limits to territorial nationalization in election support for an independence-aimed regional nationalism in Catalonia. Political Geography 60: 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idescat. 2018. EULP2018-Enquesta Usos lingüístics de la població, Institut Estadístic Catalunya. Available online: https://www.idescat.cat/pub/?id=eulp (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Llaneras, Kiko. 2021. Así se Relacionan en Cataluña la Renta, el Voto, el Origen y la Independencia. El País. February 19. Available online: https://elpais.com/politica/2021/02/19/actualidad/1613741557_146092.html (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Maza, Adolfo Jesús, José Villaverde, and María Hierro. 2019. The 2017 Regional election in Catalonia: An attempt to understand the pro-independence vote. Economia Política 36: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miley, Thomas H. Jeffrey. 2007. Against the thesis of the “civic nation”: The case of Catalonia in contemporary Spain. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 13: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miley, Thomas H. Jeffrey. 2013. Blocked articulation and nationalist hegemony in Catalonia. Regional and Federal Studies 23: 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miley, Thomas H. Jeffrey, and Roberto Garvía. 2019. Conflict in Catalonia: A sociological approximation. Genealogy 3: 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oller, José María, and Albert Satorra. 2017. La Cataluña immune al procès. OEC Group, SCC Barcelona, 20th April. Available online: https://societatcivilcatalana.cat/ (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Oller, Josep Maria, Albert Satorra, and Adolf Tobeña. 2019a. Secessionists vs. Unionists in Catalonia: Mood, emotional profiles and beliefs about secession perspectives in two confronted communities. Psychology 10: 336–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Oller, José María, Albert Satorra, and Adolf Tobeña. 2019b. Unveiling pathways for the fissure among secessionists and unionists in Catalonia: Identities, family language and media influence. Palgrave Communications 5: 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oller, Josep Maria, Albert Satorra, and Adolf Tobeña. 2019c. Pathways and Legacies of the Secessionist Push in Catalonia: Linguistic Frontiers, Economic Segments and Media Roles within a Divided Society. Policy Network Publications. October. Available online: https://policynetwork.org/publications/papers/pathways-and-legacies-of-the-secessionist-push-in-catalonia/ (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Oller, Josep Maria, Albert Satorra, and Adolf Tobeña. 2020. Privileged rebels: A longitudinal analysis of distinctive economic traits of Catalonian secessionism. Genealogy 4: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, Karl. 1904. Mathematical Contributions to the Theory of Evolution. London: Dulau and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos, Pere. 2020. La justicia obliga a un mínimo del 25% de enseñanza en castellano en Cataluña: Una sentencia del Tribunal Superior Catalán considera “residual” el uso que se hace ahora de esta lengua. El País. December 17. Available online: https://elpais.com/espana/catalunya/2020-12-17/el-tsjc-obliga-a-un-minimo-del-25-de-ensenanza-en-castellano.html (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Soler-Carbonell, Josep, Lídia Gallego-Balsà, and Victor Corona. 2016. Language and education issues in global Catalonia: Questions and debates across scales of time and space. Language, Culture and Curriculum 29: 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tobeña, Adolf. 2017. La pasión Secesionista: Psicobiología del Independentismo. Barcelona: EDLibros. [Google Scholar]

- Tobeña, Adolf. 2021. Fragmented Catalonia. London: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Ucelay-da-Cal, E. 2018. Breve Historia del Separatismo en Cataluña. Barcelona: Penguin Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Vergés-Gifra, Joan, and Macià Serra. 2021. Is there an ethnicity bias in Catalan secessionism?: Discourses and political actions. Nations and Nationalism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, Francesc Xavier. 2020. Language demography. In Manual of Catalan Linguistics. Edited by Joan A. Argenter and Jens Lütdke. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 629–48. [Google Scholar]

- Vilarrubias, Mercè. 2018. Por Una Ley de Lenguas: Convivencia en el Plurilingüismo. Barcelona: Deusto. [Google Scholar]

- Woolard, Kathryn A. 2016. Singular and Plural: Ideologies of Linguistic Authority in 21st Century Catalonia. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| Education System | Trilingual (Catalan, Spanish, and English Languages) | Bilingual/Balanced Catalan and Spanish | Catalan, Essentially | Spanish, Essentially | Parents’ Choice | DK/NA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preference of Option 1, Q05 (%) | 64.1 | 21.1 | 9.0 | 5.0 | --- | 0.8 |

| Preference of Option 2, Q06 (%) | 53.4 | 21.4 | 12.0 | 4.7 | 6.6 | 1.9 |

| Yes | No | DK/NA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you felt discriminated against because of your language in Catalonia? Q15 | 21.4 | 78.0 | 0.6 |

| Do you agree that establishments that do not label their products in Catalan should be fined? Q16 | 4.9 | 82.0 | 13.1 |

| Variable | d.f. | p-Value | C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language variables | ||||

| Q03.1 Family Language | 727.4 | 9 | ≤10−16 | 0.7489 |

| Q03.3 Writing Language | 583.8 | 12 | ≤10−16 | 0.7006 |

| Origin and nationality | ||||

| B01 Family Origin | 507.4 | 6 | ≤10−16 | 0.7101 |

| Q18 National Identity Feelings | 375.8 | 15 | ≤10−16 | 0.6031 |

| Q21 Nationality | 303.9 | 9 | ≤10−16 | 0.5570 |

| B02 Mainly Catalan Identity | 322.5 | 3 | ≤10−16 | 0.6979 |

| Education Language Issues | ||||

| Q09 Education Authority | 102.0 | 12 | ≤10−15 | 0.5164 |

| Q07.3 Education basically in Catalan is detrimental from labour point of view | 52.3 | 15 | ≤10−5 | 0.3890 |

| Q05 Public Education Language | 119.3 | 12 | ≤10−16 | 0.3767 |

| Q06 Public Education Language Format | 105.7 | 15 | ≤10−8 | 0.3567 |

| Q07.2 Education system generates detrimental effects to non catalan mother language students | 35.7 | 15 | 0.0020 | 0.3275 |

| Q07.4 Common Spanish exam | 27.9 | 15 | 0.0225 | 0.2919 |

| 07.1 First language in school | 25.9 | 15 | 0.0395 | 0.2818 |

| Q08 Textbooks language | 22.1 | 9 | 0.0085 | 0.2618 |

| Opinion on the secession campaign (procés) | ||||

| Q14.1 Damage to social harmony among Catalonians | 126.4 | 6 | ≤10−16 | 0.4099 |

| Q11 Image of Catalonia affected | 86.0 | 9 | ≤10−8 | 0.3246 |

| Q14.2 Damage to social harmony between Spaniards and Catalonians | 54.8 | 6 | ≤10−8 | 0.2789 |

| Q10 Region’s economy affected | 50.9 | 9 | ≤10−7 | 0.2539 |

| Q13 Effect on Catalan institutions | 33.2 | 9 | 0.0001 | 0.2066 |

| Q15 Feelings of discrimination | 27.7 | 6 | 0.0001 | 0.2010 |

| Q16 Linguistic fines | 27.5 | 6 | 0.0001 | 0.2001 |

| Q12 Image of Spain affected | 15.8 | 9 | 0.0716 | 0.1438 |

| Reference population variables | ||||

| Q19 Labour status | 71.8 | 18 | ≤10−7 | 0.2987 |

| Q02 Categorized Age groups | 53.6 | 9 | ≤10−7 | 0.2601 |

| Q17 Left-Right Ideology | 52.4 | 15 | ≤10−5 | 0.2575 |

| Q20 Level of studies | 33.0 | 6 | ≤10−4 | 0.2186 |

| Q01 Gender | 3.9 | 3 | 0.2676 | 0.0885 |

| Variable | d.f. | p-Value | C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language variables | ||||

| Q03.1 Family Language | 439.2 | 15 | ≤10−16 | 0.6374 |

| Q03.2 Mother Language | 375.8 | 15 | ≤10−16 | 0.6031 |

| Q03.3 Writing Language | 348.8 | 20 | ≤10−16 | 0.5681 |

| Origin and nationality | ||||

| B01 Family Origin | 309.7 | 10 | ≤10−16 | 0.5951 |

| Q21 Nationality | 187.1 | 15 | ≤10−16 | 0.4580 |

| Education Language Issues | ||||

| Q09 Education Authority | 187.9 | 20 | ≤10−16 | 0.6277 |

| Q05 Public Education Language | 220.9 | 20 | ≤10−16 | 0.4752 |

| Q07.3 Education basically in Catalan is detrimental from labour point of view | 92.6 | 25 | ≤10−8 | 0.4712 |

| Q06 Public Education Language Format | 212.6 | 25 | ≤10−16 | 0.4583 |

| Q07.2 Education system generates detrimental effects to non catalan mother language students | 79.0 | 25 | ≤10−6 | 0.4412 |

| Q07.4 Common Spanish exam | 39.0 | 25 | 0.0370 | 0.3234 |

| 07.1 First language in school | 32.8 | 25 | 0.1374 | 0.2986 |

| Q08 Textbooks language | 27.9 | 15 | 0.0225 | 0.2918 |

| Opinion on the secession campaign (procés) | ||||

| Q14.1 Damage to social harmony among Catalonians | 188.1 | 10 | ≤10−16 | 0.4869 |

| Q11 Image of Catalonia affected | 159.0 | 15 | ≤10−16 | 0.4273 |

| Q10 Region’s economy affected | 118.7 | 15 | ≤10−16 | 0.3758 |

| Q13 Effect on Catalan institutions | 88.6 | 15 | ≤10−11 | 0.3291 |

| Q16 Linguistic fines | 59.7 | 10 | ≤10−8 | 0.2905 |

| Q14.2 Damage to social harmony between Spaniards and Catalonians | 59.4 | 10 | ≤10−8 | 0.2898 |

| Q12 Image of Spain affected | 29.5 | 15 | 0.0138 | 0.1953 |

| Q15 Feelings of discrimination | 26.0 | 10 | 0.0038 | 0.1947 |

| Reference population variables | ||||

| Q17 Left-Right Ideology | 146.1 | 25 | ≤10−16 | 0.3908 |

| Q19 Labour status | 59.9 | 30 | 0.0009 | 0.2603 |

| Q20 Level of studies | 46.0 | 10 | ≤10−5 | 0.2565 |

| Q02 Categorized Age groups | 48.6 | 15 | ≤10−4 | 0.2484 |

| Q01 Gender | 3.7 | 5 | 0.5905 | 0.0860 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oller, J.M.; Satorra, A.; Tobeña, A. Parochial Linguistic Education: Patterns of an Enduring Friction within a Divided Catalonia. Genealogy 2021, 5, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030077

Oller JM, Satorra A, Tobeña A. Parochial Linguistic Education: Patterns of an Enduring Friction within a Divided Catalonia. Genealogy. 2021; 5(3):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030077

Chicago/Turabian StyleOller, Josep Maria, Albert Satorra, and Adolf Tobeña. 2021. "Parochial Linguistic Education: Patterns of an Enduring Friction within a Divided Catalonia" Genealogy 5, no. 3: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030077

APA StyleOller, J. M., Satorra, A., & Tobeña, A. (2021). Parochial Linguistic Education: Patterns of an Enduring Friction within a Divided Catalonia. Genealogy, 5(3), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030077