Categorization and Stigmatization of Families Whose Children Are Institutionalized. A Danish Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Categorization

“Categories are organizing principles in the way we understand and act in the world and the ways we relate to and interact with each other”.

1.2. Stigmatization

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Creating Categories

3.1.1. Roles of Professionals

“I offer them (the parents) solutions on how to cooperate with their child without hurting them, for example by greeting them as they walk in the door (when they go back home) instead of scolding them for leaving the bag pack on the floor”.(family therapist)

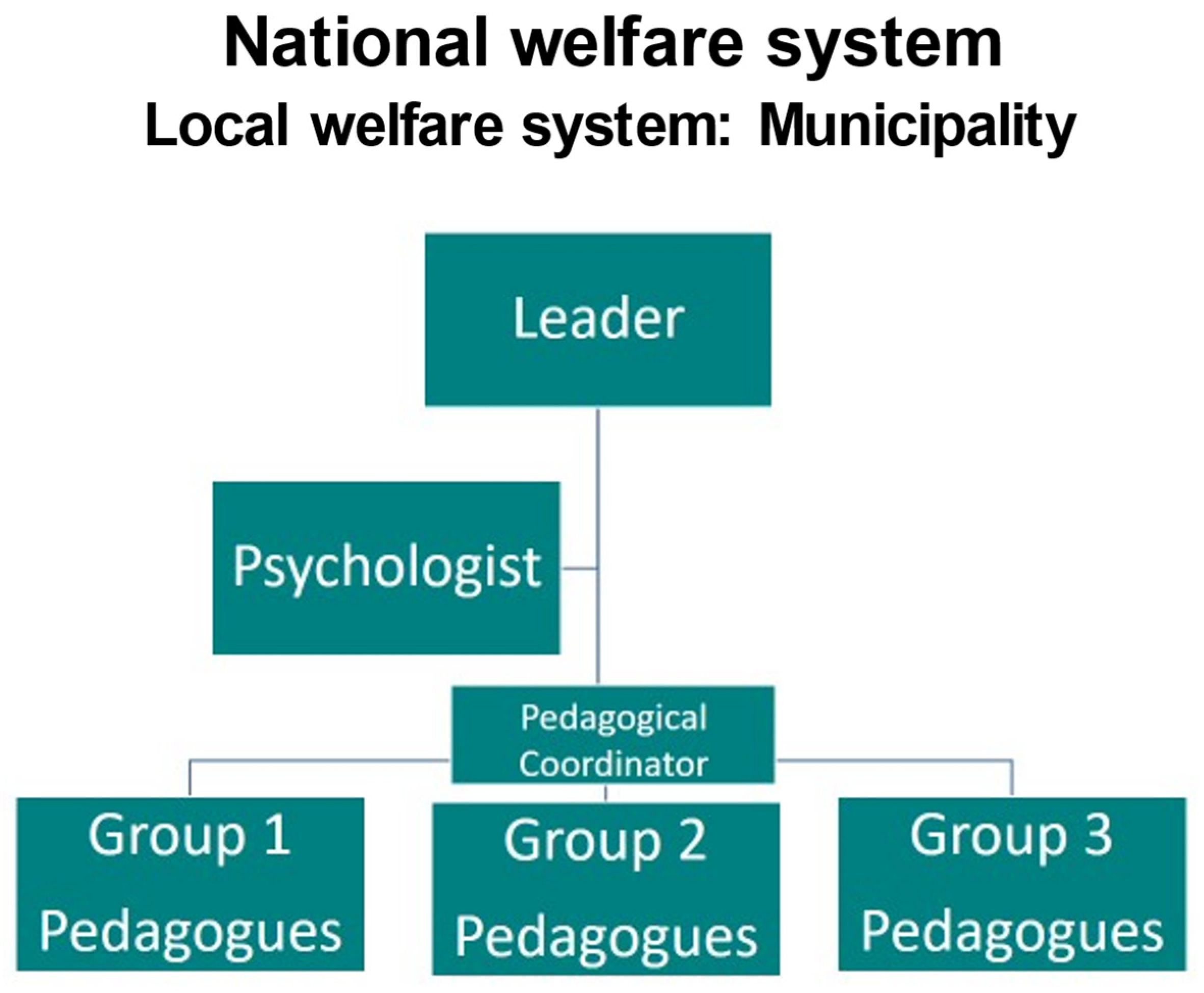

3.1.2. The Institution as Part of the Wider Welfare System

“Talking about the Danish perspective, the Danes themselves are since 1960 building up the welfare state. As a kind of contract. (…) They pay taxes, not gladly, but they pay to make everybody equal and to give all the same opportunities. But I think the Danes say ‘if institutions can help them, it’s fine. But if you come with the multicultural perspective, I understand that parents reject it [the decision to place the children in the institution]. Because it also brings shame: you can’t take care of your kids”.(pedagogue)

“For the first time, I can imagine, they [the parents] say to themselves ‘I cannot at the moment, because of this and that, raise my child myself, so I give it to the institution. It is one thing I can imagine for the parent. Cause it might be filled with shame, but it can also be a form of ‘Am I able to?’; ‘Am I a bad parent?’”.(pedagogue)

“With the family, we have been developing [the relationship] ourselves, but then still it comes out to what we are thinking. Like, the apple does not fall far from the tree. Sometimes you think, instead of putting everything on us, I can also say why you do not take a little bit more care of your kid. […] why are they where they are [in the institution]? I think that it comes from that [the parents], that the kid is here”.(pedagogue)

“Those people live there. The surroundings… we could see there were many problems with the police and all, burnings of cars, etc. The Aalborg Øst could live a life on its own, it already, the stigmatization is already there, without reflecting on it”.(pedagogue)

“We say, ‘Holy shit, why don’t the parents do this?’ Or, if they have a car, why do we need to go pick up the child? Why can’t the father pick her up? (..) We, professionals, are alone with three other kids here, we must watch them, and they still ask us to go to pick their kids up and bring the kid home for the weekend. But we can’t do everything. It is not our responsibility to drop their kids off”.(pedagogue)

“On one level, yes, we have ‘sinky’, which is an old Danish word to refer to mentally disabled, after the IQ test. It means the kid is a little bit disabled, you know, mentally. That’s on one level. Of course, on another level, the professional level, we also think about how we can help him. But [talking about difficult relationships with particular families] I am thinking about a mother, for example, it’s better to take care of her than of her kids. We do it sometimes, but when our pedagogical approach doesn’t work, I think out of a kind of frustration, I think why the parents can’t take care of their kids, why are they not doing it themselves? But this is more out of frustration, and we are not really labeling”.(pedagogue)

3.1.3. The Influence of the Local Government in Working with Categories

“The counselor first places the children in one institution, and then it doesn’t work, and the children are placed in another institution, and then it doesn’t work. But here in our institution, it is different. In our institution, we are very flexible with our treatments, we have high frustration tolerance, if the kids ruin the room or they misbehaved and did not collaborate, we do not kick them out, but we try to work with them individually. We do not have this punishment treatment like other institutions do. And I do not understand how we can still do this in Denmark. I think when we do like this, we are just like their parents. In Denmark, we have public and private institutions, and a lot of private institutions work like this, most of their professionals are not educated, and they have a primitive way of understanding the kids. They can do things that still are legal, for instance, take away the internet or the telephone (as a form of punishment), but they do it anyway because they believe that is the right way to manage the kid”.(family therapist)

“But all documentation is the most important thing in our work, because it describes the treatment and the child. It is why we are allowed to have children here, because we are able to make our documentation. Some of the things our institution is well known for is the documentation and our treatment. It matters”.(family therapist)

“They (the kommune) are differentiating more and more where to put the money. If you say the kids are going to school every day, we can put some money somewhere else. Now the relationship with the parents is very good, so they can go home more (every weekend going home), it means that we only pay five days per week for the institution.”(pedagogue)

“The kommune would say, ‘Ok. How many hours to spend with them?’ I would say 10 h. Ok and then sometimes I have been working with them 5 times and sometimes 2 years. It’s very difficult to say 10 times (…) because people that we are talking about have tough problems”.(family therapist)

“The connection between the parents, the children, and us is the counselor [from the municipality]. We always have to refer to the counselor. Two times a year, the counselor comes to our institution and checks our work, if we are getting anywhere with the work we are doing. And this is very good for me because every institution has to look at themselves every time and ask ‘Are we able to solve the problem? Or is it better to place the kid somewhere else?’”.(family therapist)

“That is the strength, that the family work is important. This was also the kommune’s idea, you can say. (..) Because the kommune [here intended as the law] says that the main issue/concern is the child and after that we can look at the family. So, we have to take each case alone and solve it. Maybe some families have lots of problems themselves, and they don’t accept that the child is placed in the institution. So we have to work with that first if they are negative about it. First, you have to place the child and then you can look at the family”.(pedagogue)

“With the kommune we are using something called the ICS triangle where everything about the child is put in. The social worker in the kommune is making her plan for the child from this triangle. (..) This ICS is part in two: resources and non-resources. So, when we are writing a report every six months, we are writing about the last six months what was about resources and what was not”.(Family therapist)

3.1.4. Professionals’ Attitudes within the Institution

“We have two groups of children: one is more flexible, and one is more restricted in how much and how long and when they [the parents] can see them. The one more flexible, for instance one kid can say ‘I want to see my mom this afternoon, can we call her?’ And the pedagogues will call and perhaps bring the kid for a couple of hours to see her mom. But primarily the counselor decides in which group the kid and their parents are placed”.(family therapist)

“Here, we follow a mentalization-based theory, and attachment theory, but we also create our own knowledge. It is about the fact that these kids do not understand their own inner world, their feelings and emotions and they are not able to mentalize and understand why they (the kids) react like that. They react, but they cannot say it is because I am angry or because I am sad. So, the pedagogue needs to know what the normal development of the child is. So, they need to recognize what is normal and what is dysfunctional for the kids. They need to learn the distinction between the two, normal and dysfunctional.

We work in the relationship with the kids. We do what normal parents do with normal kids. For instance, the baby (child) starts to cry because there is an airplane [as to say the kid got scared by the noise] and the kid starts to cry and the parent reacts surprised and says to the baby ‘Oh! you got scared, come here and I comfort you.’ But our kids here do not receive this education. So, we always try to put in words what we think they [the kids] are feeling so they start to learn it and they feel understood”.(family therapist)

“We have some parents that are very disturbed, and have a lot of personality disorders, and they can be extremely wild, and of course their relationship with the kids is not always good. But we think that they are their parents. (...) So, we work a lot on the relationship between the parents and their children. We talk with the parents almost weekly; we have a family therapist, and this is also a mentalizing way. We try to make them understand what is happening to their kid’s life, so maybe they can understand, and maybe they take some responsibility to be the adult. A lot of times, it is like seeing two kids together when we see the parents and the child, and we have to teach them how to be the adult. For instance, when the parents are drug addicts or have alcohol problems, we do supervise the relationship with parents and children”.(family therapist)

“My mission is psychoeducation and therapy for the parents, for the family and the network. It aims to solve the problem for the child, not to help them to solve their problems. Those, they have to solve themselves. (…) And it’s all based on the values from the kommune and from the institution. So my job is not solving the problems but talking about the problems, to give another side of them”.(family therapist)

“We’ve heard from some kids where the parents were very uncooperative at the time, later (..) the parents have changed their thoughts about their kid (…) But it is a long process for them, of course. It implies many things: when you talk about shame, not being able to be a good parent while the expectations are of you being a good parent. Now, if they come to that recognition, there also might be big expectations towards us. ‘Now I give my kid to you, and I expect you to give the best work you can do as a professional with my kid’”.(pedagogue)

3.1.5. The Institutional Function of Categories

“You can also think about parents who have kids and who have a network, social and cultural and economic capital and all, who have a network inside a kommune, maybe it’s easier for them to place a child in an institution. But it’s just speculation”.(pedagogue)

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

What is the categorization of families and their characteristics made by professionals in the institution and what is the impact on the daily practice of professionals working with the families?

Appendix A.1. Introduction

Appendix A.2. The Institution and Families

- Kindly explain what type of relationship you have with the parents of children at the institution. Do you think this also reflects the overall vision of the institution?

- -

- Can you relate to the families?

- -

- How do you see the collaboration with families?

- -

- For example: a percentage of the time you spend working with families.

- -

- The actual work, activities, administration work, follow-up, how you would like it to be, etc… What is your personal belief of what family should be like?

Appendix A.3. Stigmatization

- General: What is your personal belief about the role of families for children? (How does he perceive the concept of family?)

- What is your personal belief about the role of families for children placed in the institution?(If the pedagogue answers the question directly referring to families in the institution, we can ask whether he sees a difference with families who do not have their children at the institution, for example).

- Do you think parents face different challenges than other parents in society? What are those challenges and concerns (e.g., different attitudes/labels of people)? Do you think these challenges reflect/affect the involvement of parents in the institution?

Appendix A.4. Categorization

- Can you describe the characteristics of families you work with in the institution? (Ask about capitals, where they live, what their education level is, leisure time, income, values, skills.)

- How much freedom do the individual pedagogues have to shape the relationship with the parents? (e.g., Is there a protocol on how to involve the parents, or when to stop trying?)

- Have you experienced discomfort dealing with (a certain) case? If yes, can you give an example? How did you deal with it?

- What are the factors that influence the decision of the kommune regarding the intensity of benefits (privileges) given to parents (visits, for example)?

- What kind of labels (formal and informal) do the families have in the daily routine? (How do professionals refer to parents?)

- Have you seen a case of parents who came in with a certain label from the family group that changed over time? Can you give an example (e.g., forced placement)?Has your own attitude and behavior towards families changed?

- What kind of families would be able to take care of their children when the treatment at the institution has finished?

Appendix A.5. Extra

- Do perceptions of parents made by the professionals affect the relationship between them and the parents? If yes, how?

Appendix B

What is the categorization of families and their characteristics made by professionals in the institution and what is the impact in the daily practice of professionals working with the families?

Appendix B.1. Introduction

Appendix B.2. The Institution and Families

- Kindly explain what type of relationship you have with the parents of children at the institution. Do you think this also reflects to the overall vision of the institution?

- Can you relate to the families?

- How do you see the collaboration with families?

- For example: a percentage of the time you spend working with families.

- The actual work, activities, administration work, follow-up, how you would like it to be, etc. … What is your personal belief of what family should be like?

- In general, do all institutions who work like this institution have the same organizational structures and functions, and if not, what is the difference? Are professional roles (as a family therapist) in all institutions the same?

- What are the characteristics set by the kommune to assess families (into groups A, B, C)?

Appendix B.3. Stigmatization

- General: What is your personal belief about the role of families for children? (How does he perceive the concept of family?)

- What is your personal belief about the role of families for children placed in the institution?(If the family therapist answers the question directly referring to families in the institution we can ask whether she sees a difference with families who do not have their children at the institution, for example).

- Do you think parents face different challenges than other parents in society? What are those challenges and concerns (e.g., different attitudes/labels of people)? Do you think these challenges reflect/affect the involvement of parents in the institution?

Appendix B.4. Categorization

- Can you describe the characteristics of families you work with in the institution? (Ask about capitals, where they live, what their education level is, leisure time, incomes, values, skills.)

- How much freedom do the individual pedagogues and you as a therapist have to shape the relationship with the parents? (e.g., Is there a protocol on how to involve the parents or when to stop trying? Do the individual workers work differently?)

- Have you experienced discomfort dealing with (a certain) case? If yes, can you give an example? How did you deal with it?

- What are the factors that influence the decision of the kommune regarding the intensity of benefits (privileges) given to parents (visits, for example)?

- What kind of labels (formal and informal) do the families have in the daily routine? (How do professionals refer to parents?)

- Have you seen a case of parents who came in with a certain label from the family group that changed over time? Can you give an example (e.g., forced placement)? Has your own attitude and behavior towards families changed?

- What kind of families would be able to take care of their children when the treatment at the institution has finished?

Appendix B.5. Extra

- Do perceptions of parents made by the professionals affect the relationship between them and the parents? If yes, how?

- How can policies influence the labeling done for children with behavioral problems and their families?

References

- Åge, Lars-Johan. 2011. Grounded theory methodology: Positivism, hermeneutics, and pragmatism. The Qualitative Report 16: 1599. [Google Scholar]

- Alareeki, Asala, Bonnie Lashewicz, and Leah Shipton. 2019. “Get Your Child in Order:” Illustrations of Courtesy Stigma from Fathers Raising Both Autistic and Non-autistic Children. Disability Studies Quarterly. 39. nº 4. Available online: https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/6501/5464 (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Atkinson, Paul. 2017. Thinking Ethnographically. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Balorda, Jasna. 2019. Denmark: The rise of fascism and the decline of the Nordic model. Social Policy and Society 18: 133–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEK nr 766 af. 2011. Bekendtgørelse om Uddannelse til Professionsbachelor som Socialrådgiver. Danish Law on Education for Social Work. Available online: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2011/766 (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Bos, Arhan E. R., John B. Pryor, Glenn D. Reeder, and Sarah E. Stutterheim. 2013. Stigma: Advances in Theory and Research. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 35: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1989. Social space and symbolic power. Sociological Theory 7: 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bourdieu, Pierre, Alain Accardo, and Gabrielle Balazs. 1999. The Weight of the World: Social Suffering in Contemporary Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2012. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol. 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. Edited by Harris Cooper, Paul M. Camic, Debra L. Long, Abigail T. Panter, David Rindskopf and Kenneth J. Sher. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Buscatto, Marie. 2018. Doing ethnography: Ways and reasons. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 327–43. [Google Scholar]

- CIJ-Center for Intersectional Justice. 2020. Intersectionality at a Glance in Europe. CIJ Berlin. August 12. Available online: https://www.intersectionaljustice.org/publication/2020-04-07-center-for-intersectional-justice-factsheet-intersectionality-at-a-glance-in-europe (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Cleaver, Hedy, Steve Walker, Harriet Ward, Jane Scott, Wendy Rose, and Andy Pithouse. 2008. The Integrated Children’s System: Enhancing Social Work and Inter-Agency Practice. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran, Jacqueline, Amber Berry, and Stephanie Hill. 2015. The lived experience of US parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 19: 356–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, Patrick W., and Deepa Rao. 2012. On the self-stigma of mental illness: Stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 57: 464–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Danish Family Therapy Institution. n.d. Available online: https://www.dfti.dk/uddannelser/familieterapeutuddannelse/ (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Dannesboe, Karen Ida, Dil Bach, Bjørg Kjær, and Charlotte Palludan. 2018. Parents of the Welfare State: Pedagogues as Parenting Guides. Social Policy and Society 17: 467–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Ashley, and Sabrina Gentlewarrior. 2015. White Privilege and Clinical Social Work Practice: Reflections and Recommendations. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eco, Umberto. 1995. Ur-Fascism. In The New York Review of Books. New York: The New York Review of Books, pp. 1–9. Available online: http://www.pegc.us/archive/Articles/eco_ur-fascism.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Farrugia, David. 2009. Exploring stigma: Medical knowledge and the stigmatisation of parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Sociology of Health & Illness 31: 1011–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Ara. 2012. Stigma in an era of medicalisation and anxious parenting: How proximity and culpability shape middle-class parents’ experiences of disgrace. Sociology of Health & Illness 34: 927–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershon, Ilana. 2005. Seeing like a system: Luhmann for anthropologists. Anthropological Theory 5: 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma. Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Harmondsworth: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1974. Frame Analysis: An essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, David E. 2002. ‘Everybody just freezes. Everybody is just embarrassed’: Felt and enacted stigma among parents of children with high functioning autism. Sociology of Health & Illness 24: 734–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Green, Sara, Christine Davis, Elana Karshmer, Pete Marsh, and Benjamin Straight. 2005. Living stigma: The impact of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination in the lives of individuals with disabilities and their families. Sociological Inquiry 75: 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrits, Gitte Sommer, and Marie Østergaard Møller. 2011. Categories and categorization: Towards a comprehensive sociological framework. Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory 12: 229–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedegaard, Troels Fage. 2014. Stereotypes and welfare attitudes: A panel survey of how “poor Carina” and “lazy Robert” affected attitudes towards social assistance in Denmark. Nordic Journal of Social Research 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koro-Ljungberg, Mirka, and Regina Bussing. 2009. The management of courtesy stigma in the lives of families with teenagers with ADHD. Journal of Family Issues 30: 1175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalvani, Priya. 2015. Disability, stigma and otherness: Perspectives of parents and teachers. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 62: 379–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, Christian Albrekt. 2007. The Institutional logic of Welfare Attitudes: How Welfare Regimes Influence Public Support. Comparative Political Studies, 145–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larsen, Christian Alberkt. 2008. Why Welfare States Persist: The Importance of Public Opinion in Democracies. Edited by Clem Brooks and Jeff Manza. Perspectives on Politics 6: 839–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, Christian Alberkt, and Thomas Engel Dejgaard. 2013. The institutional logic of images of the poor and welfare recipients: A comparative study of British, Swedish and Danish newspapers. Journal of European Social Policy 23: 287–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LBK nr. 1270. 2016—Bekendtgørelse af lov om Social Service. Available online: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2016/1270 (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Liberman, Zoe, Amanda L. Woodward, and Katherine. D. Kinzler. 2017. The Origins of Social Categorization. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 21: 556–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNutt, John G. 2008. Social work practice: History and evolution. In Encyclopedia of Social Work. Edited by Larry E. Davis and Terry Mizrahi. Washington, DC: NASW Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitter, Natasha, Afia Ali, and Katrina Scior. 2019. Stigma experienced by families of individuals with intellectual disabilities and autism: A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities 89: 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moesby-Jensen, Cecilie K., and Tommy Moesby-Jensen. 2016. On categorization and symbolic power in social work—The myth of the resourceful parents to children with neuro-psychiatric diagnoses. Sociologisk Forskning 16: 371–95. [Google Scholar]

- Nethercott, Kathryn. 2016. The Common Assessment Framework form 9 years on: A creative process. Child and Family Social Work. online ahead of press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaison, Anna. 2010. Creating images of old people as home care receivers. Categorizations of needs in Social Work case files. Qualitative Social Work 9: 500–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattyn, Sven, Yves Rosseel, and Alain Van Hiel. 2013. Finding our way in the social world. Social Psychology 44: 329–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieur, Annick, Lennart Rosenlund, and Jakob Skjott-Larsen. 2008. Cultural capital today. A case study from Denmark. Poetics, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, Deborah. 2012. Street-Level Bureaucrats and the Welfare State. Administration & Society 45: 1038–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scambler, Graham. 2004. Re-framing stigma: Felt and enacted stigma and challenges to the sociology of chronic and disabling conditions. Social Theory & Health 2: 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socialstyrelsen [Danish National Board of Social Services]. 2014. Barnets Velfærd ICentrum—ICS Håndbog. [Child Welfare in Focus—ICS Handbook] Odense: Socialstyrelcen. Available online: https://viden.sl.dk/media/5318/barnets-velfaerd-i-centrum.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Søren, Juul. 2009. Recognition and Judgement in Social Work. European Journal of Social Work 12: 402–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Danish National Federation of Early Childhood Teachers and Youth Educators. n.d. Available online: https://bupl.dk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/publikationer-the_work_of_the_pedagogue.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Villadsen, Kaspar, and Nanna Mik-Meyer. 2013. Power and Welfare: Understanding Citizens’ Encounters with State Welfare. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Lawrence Hsin, Arthur Kleinman, Bruce G. Link, Jo C. Phelan, Sing Lee, and Byron Good. 2007. Culture and stigma: Adding moral experience to stigma theory. Social Science & Medicine 64: 1524–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Role | Gender | Education Level | Years of Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pedagogue | Man | Professional Bachelor’s in Pedagogy/Master in Literature and Culture | 17 years |

| Family therapist | Woman | Bachelor’s in Social Work/Specialization in Family Therapy | 26 years |

| Leader (key informant) | Woman | Bachelor’s in Psychology/Specialization in Psychotherapy | 10 years |

| Pedagogues (exercise) | 3 Women/6 Men | Professional Bachelor’s in Pedagogy | ------------------ |

| Stigmatization | Categorization | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience with Families | Professional Views | Society Views | Family Challenges | Social Capital | Economic Capital | Cultural Capital | Symbolic Capital | Others/Notes |

| A Binary View of Families | |

|---|---|

| Resourceful Parents | Non-Resourceful Parents |

| Positive contact with professionals | Negative contacts with professionals |

| Regular contact with professionals | Non-regular contact with professionals |

| Regular positive contact with children | Non-regular contact with their children |

| High level of engagement in children’s life | Low level of engagement in children’s life |

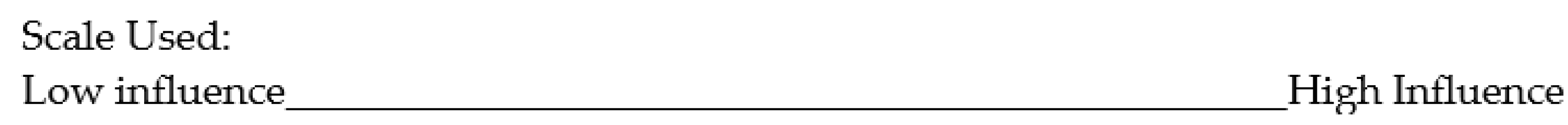

| Lowest Influence | Medium Influence | Highest Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Education level Income Assets (car, house) Success Career Economy/financial Clever (High IQ) | Routine Inventive Communication skills Social network Stigmatized Engagement in social activities Imaginative | Honest Learning/open attitude Loyal Parenting skills Management Reflexivity |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Acosta-Jiménez, M.A.; Antonios, A.M.; Meijer, V.; Di Matteo, C. Categorization and Stigmatization of Families Whose Children Are Institutionalized. A Danish Case Study. Genealogy 2021, 5, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030076

Acosta-Jiménez MA, Antonios AM, Meijer V, Di Matteo C. Categorization and Stigmatization of Families Whose Children Are Institutionalized. A Danish Case Study. Genealogy. 2021; 5(3):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030076

Chicago/Turabian StyleAcosta-Jiménez, María Alejandra, Anna Maria Antonios, Veerle Meijer, and Claudia Di Matteo. 2021. "Categorization and Stigmatization of Families Whose Children Are Institutionalized. A Danish Case Study" Genealogy 5, no. 3: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030076

APA StyleAcosta-Jiménez, M. A., Antonios, A. M., Meijer, V., & Di Matteo, C. (2021). Categorization and Stigmatization of Families Whose Children Are Institutionalized. A Danish Case Study. Genealogy, 5(3), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030076